Abstract

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the most common cause of dementia. Diagnosing AD before symptoms arise will facilitate earlier intervention. The early diagnostic approaches are thus urgently needed.

Methods

The multifunctional nanoparticles W20/XD4-SPIONs were constructed by the conjugation of oligomer-specific scFv antibody W20 and class A scavenger receptor (SR-A) activator XD4 onto superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs). The SPIONs’ stability and uniformity in size were measured by dynamic light scattering and transmission electron microscopy. The ability of W20/XD4-SPIONs for recognizing Aβ oligomers (AβOs) and promoting AβOs phagocytosis was assessed by immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry analysis. The blood–brain barrier permeability of W20/XD4-SPIONs was determined by a co-culture transwell model. The in vivo probe distribution of W20/XD4-SPIONs in AD mouse brains was detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Results

W20/XD4-SPIONs, as an AβOs-targeted molecular MRI contrast probe, readily reached pathological AβOs regions in brains and distinguished AD transgenic mice from WT controls. W20/XD4-SPIONs retained the property of XD4 for SR-A activation and significantly promoted microglial phagocytosis of AβOs. Moreover, W20/XD4-SPIONs exhibited the properties of good biocompatibility, high stability and low cytotoxicity.

Conclusion

Compared with W20-SPIONs or XD4-SPIONs, W20/XD4-SPIONs show the highest efficiency for AβOs-targeting and significantly enhance AβOs uptake by microglia. As a molecular probe, W20/XD4-SPIONs also specifically and sensitively bind to AβOs in AD brains to provide an MRI signal, demonstrating that W20/XD4-SPIONs are promising diagnostic agents for early-stage AD. Due to the beneficial effect of W20 and XD4 on neuropathology, W20/XD4-SPIONs may also have therapeutic potential for AD .

Keywords: magnetic resonance imaging, diagnosis, Alzheimer’s disease, β-amyloid, oligomer, class A scavenger receptor

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects more than 50 million people over the world. The extracellular plaques of β-amyloid (Aβ) and intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles accumulated by hyperphosphorylated tau remain the primary neuropathologic hallmarks for AD.1 Despite decades of research, there are still no effective strategies to halt AD progression. Numerous Phase III clinical trials have failed to demonstrate benefits.2 One significant challenge for clinical trials is the lack of objective and effective diagnostic criteria as well as appropriate biological markers. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) assay as a traditional diagnostic method has shown promise,3,4 but the accuracy of these assays is limited and spinal taps are invasive.5 AD imaging is another promising diagnostic strategy. Molecular imaging using the positron emission tomography (PET) has been a great technical advance to reveal the presence of Aβ plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in AD brains. However, the correlation between AD dementia and amyloid plaques imaged by PET in many individuals is not satisfactory,6,7 moreover, Aβ plaques are not present in the earlier stage of AD.

The primary neuroimaging modality is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is recommended for most of the AD patients to provide diagnostic confirmation on cognitive decline. MRI is also an invaluable imaging method for AD research potential. Compared with PET, MRI has several advantages, such as no radiation, cheaper, and greater resolution. In addition, MRI scanners are about 10 times more than PET scanners worldwide.8,9 However, magnetic resonance (MR)-based molecular imaging techniques still need to be fully developed to provide PET-like sensitivity. Increasing evidence demonstrates that the early intervention may effectively delay the progression of AD.10 Therefore, sensitive MRI probes for the special biomarkers at an earlier stage of AD are necessary for diagnostic accuracy and further disease intervention.

The misfold and accumulation of Aβ is considered a key step in AD progression, which occurs 10–15 years before symptom onset.1 Aβ is prone to aggregate into oligomers, protofibrils, and fibrils.11 The amyloid cascade hypothesis suggests that Aβ oligomers (AβOs), but not monomers or fibrils, are the main toxic forms, which lead to neuron damage and thus dementia.12 Lots of evidences indicated that AβOs promoted tau pathology,13 impaired axonal transport,14,15 deteriorated synapse function,16,17 induced oxidative stress,18 endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress,19 and neuroinflammation.20 Based on the important role of AβOs in AD, and the appearance of AβOs in AD brains decades before the symptom onset,21–23 AβOs may be a more appropriate biomarker and more appealing target than plaques at the early stage of AD. Targeting AβOs will be attractive diagnostic strategies for AD.

In previous studies, we reported that the SPIONs conjugated with an oligomer-specific single-chain variable fragment (scFv) antibody W20 specifically recognized amyloid oligomers in brains to provide MRI signal, distinguishing Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease from healthy controls.24 Moreover, W20-SPIONs may offer a safer approach for targeting AβOs by avoiding the induction of inflammatory responses due to a lack of effector function. However, W20 showed low efficiency in clearing AβOs. Here we further introduced heptapeptide XD4 to SPIONs, which was isolated by phage display, and had the ability to activate the class A scavenger receptor (SR-A) of microglia and promotes microglial phagocytosis of AβOs.25 In present work, we conjugated W20 and XD4 to PEGylated SPIONs to construct an AβO-targeted molecular MRI probe for early detecting neurotoxic oligomers in APP/PS1 mouse model of AD.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Aβ42 and XD4 peptide were synthesized from Chinese Peptide Company (Hangzhou, China). Antibodies: 6E10 (anti-Aβ1-16 antibody, Signet, SIG39300), W20 (oligomer-specific antibody, prepared by our laboratory), anti-GAPDH antibody (CST, 2118S), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz, I1112) and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody (Abcam, ab150084). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from ZSGB Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China).

Preparation of the Conjugated-SPIONs

The PEG-SPIONs were synthesized by a “one-pot” method according to previous protocols.24 Briefly, 2.1 g of Fe(acac)3, 7.9 mL of oleylamine, and 24 g of HOOC-PEG-COOH (Mn = 2000) were dissolved in 100 mL of diphenyl ether. The solution was purged with nitrogen for 2 h with stirring at 400 rpm. The reaction mixture was incubated at 80°C for 4 h and then heated quickly to reflux within 10 min and maintained at reflux for 30 min. After that, ether was added to precipitate the nanoparticles. The precipitate was then redissolved in ethanol followed by the addition of ether as precipitant for three cycles. The obtained PEG-SPIONs were dissolved in PBS for further experiments.

Two-milligram PEG-coated SPIONs were dissolved in 950 μL PBS buffer with 2.50 μmol EDC and 6.25 μmol sulfo-NHS added and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. After that, different molecular ratio of W20 and/or XD4 was added and the reaction was continued overnight at 4°C. Then, the products were collected by centrifugation at 25,000 rpm, re-dissolved in PBS, and kept at 4°C for use. The conjugative efficiency for W20 or XD4 was calculated by determining the residual protein amount in the supernatant using BCA assay. The supernatant was transferred to a 3 kD ultrafiltration tube and centrifuged for 15 min. The residual XD4 was measured by the protein amount in the filtrate fraction, and the residual W20 can be determined by the protein amount in the cut-off solution. The conjugative efficiency was calculated according to the following equation:

|

For in vivo real-time imaging study, W20/XD4-SPIONs or unconjugated-SPIONs were conjugated to fluorescent dyes using a Cy7 Labeling Kit (FANBO biochemicals, CAT#1060). The Cy7-labeled SPIONs were separated by using a 10 kD ultrafiltration tube to remove excess dye.

Dot-Blot

To detect W20 conjugation on the SPIONs, serials of SPIONs and W20 were applied onto nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% milk in 1×PBS with Tween-20 (0.1% PBST) and incubated with anti-c-myc antibody (1:1000) at room temperature for 1 h. Then, the bound antibodies were probed with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (1:5000). Immunoreactive blots were visualized with an ECL chemiluminescence kit and quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Characterization of W20/XD4-SPIONs

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was used to characterize the hydrodynamic size of the SPIONs by Zetasizer Nano ZSP (Malvern, UK). The morphology of the SPIONs was detected by a transmission electron microscopy (TEM, HT7700, HITACHI, Japan). The average diameters of the SPIONs were determined by measuring more than 100 quasi-spherical particles. T2 relaxivity of the SPIONs was measured by a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer (NMI20, Niumag Corporation, Shanghai, China) at 1.42 T and 60 Hz. T2 relaxation times for the SPIONs were correlated with iron concentration. r2 values were calculated by the slope of 1/T2 versus iron concentration. Inductively coupled plasma spectrometry (ICP) was used to determine the iron content in the SPIONs.

Aβ42 Oligomers Preparation

Aβ42 peptide monomers were dissolved in PBS at 1 mg/mL and incubating at 37°C for 2 h without agitation, and then Aβ42 oligomers were separated and collected by size exclusion chromatography (SEC). In phagocytosis studies, 1 μM of Aβ42 oligomers were used in BV-2 cell cultures.

Immunocytochemistry

BV-2 cells were purchased from the cell line resource center of Peking Union Medical College, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Cells were seeded on coverslips in 12-well plates at 5×105 cells/well and exposed to Aβ42 oligomers (1 μM) with or without SPIONs for 1.5 h. Then, cells were fixed and immunostained using 6E10 (1:100), anti-c-myc (1:100), or anti-SRA (1:100) antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated (1:300) or Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated (1:300) secondary antibodies, respectively. Subsequently, cells were counterstained with Hoechst (1:10,000). Images were acquired using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP8).

Flow Cytometry

The internalized FITC-AβOs in BV-2 cells were performed by flow cytometry analysis using a FACSCalibur Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Trans-Well Model

The upper chambers of the in vitro BBB trans-well system (PET membrane, 0.4 μm of pore size, Thermo) were seeded with b. End 3 cells (obtained from the cell line resource center of Peking Union Medical College, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences) at 2×105 cells/well in a 12-well plate. SH-SY5Y cells (recipients, obtained from the cell line resource center of Peking Union Medical College, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences) were seeded at 5×105 cells/well. W20/XD4-SPIONs were added to the upper chambers and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Then, SH-SY5Y cells were fixed and immunostained with anti-c-myc antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody. Slides were then counterstained with Hoechst and finally visualized with a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP8).

MTT Assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1×105 cells/well per 100 μL of DMEM. Then, W20/XD4-SPIONs or unconjugated-SPIONs were added to the cells for an additional 48 h-incubation at 37°C. After that, 20 μL of 5 mg/mL MTT was added to each well and incubated with cells for 3 h. The supernatants in each well were replaced with 150 μL DMSO and the absorbance was measured using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at 570/630 nm.

Immunoprecipitation

The SPIONs were pre-incubated with AβOs for 2 h and then co-incubated with the homogenized membrane extracts of BV-2 cells for an additional 4 h at room temperature. The immunoprecipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation at 25,000 rpm for 1 h and then separated by 4–12% SDS-PAGE gel (Invitrogen). Gels were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Then, the membrane was probed by anti-SRA antibody (1:1000) and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Immunoreactivity was detected with an ECL chemiluminescence kit and analyzed using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from BV-2 cell cultures pre-treated Aβ with or without conjugated-SPIONs using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). cDNA was prepared from 1.5 μg of total RNA using a PrimeScript RT-PCR kit (Takara, RR037A). Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out using the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies) with SYBR Mix (Applied Biosystems, 4,472,908). The following primers were used:

5ʹ- ACATCACCAACGACCTCAGACT −3ʹ and

5ʹ- AGTTTGTCCAGTAAGCCCTCTG −3ʹ for SR-A;

5ʹ- TTTGGAGTGGTAGTAAAAAGGGC −3ʹ and

5ʹ- TGACATCAGGGACTCAGAGTAG −3ʹ for SR-B;

5ʹ- GTGCTGGTTCTTGCTCTATGG −3ʹ and

5ʹ- TTCCTGTGTTCAGTTTCCATTC −3ʹ for RAGE;

5ʹ-TCCATGACAACTTTGGCATTG-3ʹ and 5ʹ-CAGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGA-3ʹ for GAPDH.

Animals

All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Tsinghua University Animal Care and Use Committee. Experiments were carried out according to the China Public Health Service Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Six-month-old male APPswe/PS1dE9 transgenic mice (AD mice) were originally obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Nude mice and C57 mice were obtained from Beijing Vital River Labs. Mice were housed according to the standardized conditions in the Tsinghua University animal facility.

In vivo Real-Time Imaging and the Distribution of SPIONs

Cy7-labeled W20/XD4-SPIONs or unconjugated-SPIONs were dissolved in PBS containing 15% mannitol for administration. Six nude mice were used in each group. Each mouse was intravenously administrated with 300 μL of CY7-labeled SPIONs via the tail vein (200 μmol Fe/kg body weight). The fluorescence signal was imaged using an IVIS spectrum imaging system (Kodak In-Vivo Imaging System FX Pro, USA) at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h post-administration. The organs of mice including brain, heart, liver, spleen, lungs and kidneys were collected at 0, 2, 4, 12, 24 h post administration, washed with saline, and the specific CY7 tissue fluorescence for each organ was quantified using the IVIS spectrum imaging system.

Brain MRI Imaging in vivo

AD mice or their WT littermates were received the SPIONs by intravenously administration with 300 μL of SPIONs containing 15% mannitol via the tail vein (200 μmol Fe/kg body weight). Six mice were used in each group. The animals were firstly anesthetized using 2.5% isoflurane which was then reduced to 1% for maintenance. MRI studies were performed at a 7 Tesla MRI system (Varian, US). T2* gradient-echo (GRE) imaging was performed with imaging parameters as follows: 100 μm isotropic spatial resolution; TR (repetition time) = 162.84 ms; TE (echo time) = 5.45 ms; FA = 20°; FOV (field of view) = 16×20 mm; matrix = 256×256; thickness = 0.5 mm; slices = 15; scan time = 6 min 15 s.

Immunohistochemistry and Histostaining

Mice were deeply anaesthetized and transcardially perfused with ice-cold PBS containing heparin (10 U/mL). Six mice were used in each group. The brains were removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight and processed for paraffin-embedded sections. Five μm thickness of coronal serial sections were cut on a Lecia CM1850 microtome (Leica Biosystems). Sections were incubated and blocked with 10% goat serum in 0.3% Triton X-100 PBST for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated with 6E10 antibody (1:100) and W20/XD4-SPIONs, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200) and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-c-myc antibody (1:200). Iron deposits were detected via Prussian Blue staining. All sections were imaged with an Olympus IX73 inverted microscope. Immunostaining regions were quantitively analyzed using ImageJ (NIH, USA).

Histologic Analysis

Mice were sacrificed at 7d post-administration. Six mice were used in each group. The organs were collected and processed for paraffin-embedded sections. For H&E staining, the sections were firstly stained with hematoxylin for 5 min, washed in running water for 10 min, and counterstained with eosin for 1 min. Then, the sections were dehydrated in 95% alcohols twice and imaged with an Olympus IX73 inverted microscope.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism v.5., and significance was assessed using Student’s t-test, one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test, as appropriate. Data were displayed as group means ± SEM, and P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

W20/XD4-SPIONs Characterization

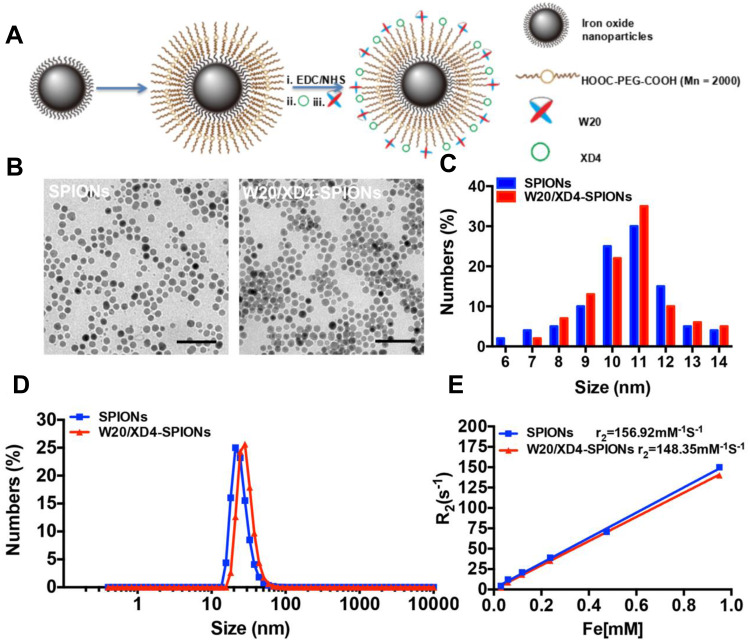

W20/XD4-SPIONs were prepared by conjugating PEG-coated SPIONs with W20 antibody and XD4 peptide (Figure 1A). We determined the protein concentration of the conjugated W20 and XD4 in the W20/XD4-SPIONs system to calculate the conjugative efficiency, performed gel electrophoresis to detect the particle changes, and conducted dot-blots by using anti-c-myc and anti-SRA antibodies to detect the conjugated W20 and XD4, respectively. The results showed that the conjugative efficiency of W20 alone or XD4 alone was about 50%, but when W20 and XD4 input simultaneously, the conjugative efficiency of XD4 decreased to 19.2%, and that of W20 remained unchanged (Table S1). Gel electrophoresis in 1% agarose of all samples showed the bands of the conjugated-SPIONs were behind the unconjugated SPIONs, suggesting that XD4-SPIONs, W20-SPIONs and W20/XD4-SPIONs had larger sizes than SPIONs (Figure S1A). Moreover, dot-blot analysis using anti-c-myc antibody confirmed the conjugation of W20 on the SPIONs (Figure S1B). In Figure 4B, co-immunoprecipitation of SR-A from BV-2 cells with W20/XD4-, XD4-SPIONs in the presence of AβOs indicated the conjugation of XD4 on the W20/XD4-SPIONs and XD4-SPIONs, but not W20-SPIONs. The probe uniformity in size was characterized by TEM and dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurement, respectively (Figure 1B–D). TEM imaging showed that W20/XD4-SPIONs were mono-dispersed with the size of 11.5 ± 1.8 nm in diameter (Figure 1B and C). DLS measurement demonstrated that the hydrodynamic diameters of the unconjugated-SPIONs and W20/XD4-SPIONs were 21.1 ± 5 nm and 32.0 ± 5 nm, respectively (Figure 1D). The size distribution of W20/XD4-SPIONs determined by DLS was consistent with the physical measurements by TEM. W20/XD4-SPIONs were stable in PBS for over 6 months, with a zeta potential of approximately −15mV, and the PDI of 0.199. No agglomeration was observed by TEM at 6 months (Figure S2). The MR relaxivity of W20/XD4-SPIONs was evaluated by the r2 value, which was calculated by the spin-spin relaxation rate (R2) versus iron concentration. We observed that the r2 value of W20/XD4-SPIONs was 148.35 s−1mM−1 (Figure 1E), indicating that W20/XD4-SPIONs may offer sufficient signal sensitivity.

Figure 1.

Preparation and characterization of W20/XD4-SPIONs. (A) Schematic illustration of preparation of W20/XD4-SPIONs. (i) The carboxyl of PEG on the SPIONs was activated with EDC and NHS. SR-A activator XD4 (ii) and oligomer-specific scFv antibody W20 (iii) were conjugated to the nanoparticles. (B) The morphology of SPIONs and W20/XD4-SPIONs were imaged by transmission electron microscope (TEM) at an accelerating voltage of 100 KV. Scale bar, 50 nm. (C) The size distribution of SPIONs and W20/XD4-SPIONs. The diameters of more than 100 nanoparticles were measured and their distribution was plotted. (D) The hydrodynamic diameters of SPIONs and W20/XD4-SPIONs were detected by DLS. (E) The r2 value of the SPIONs and W20/XD4-SPIONs.

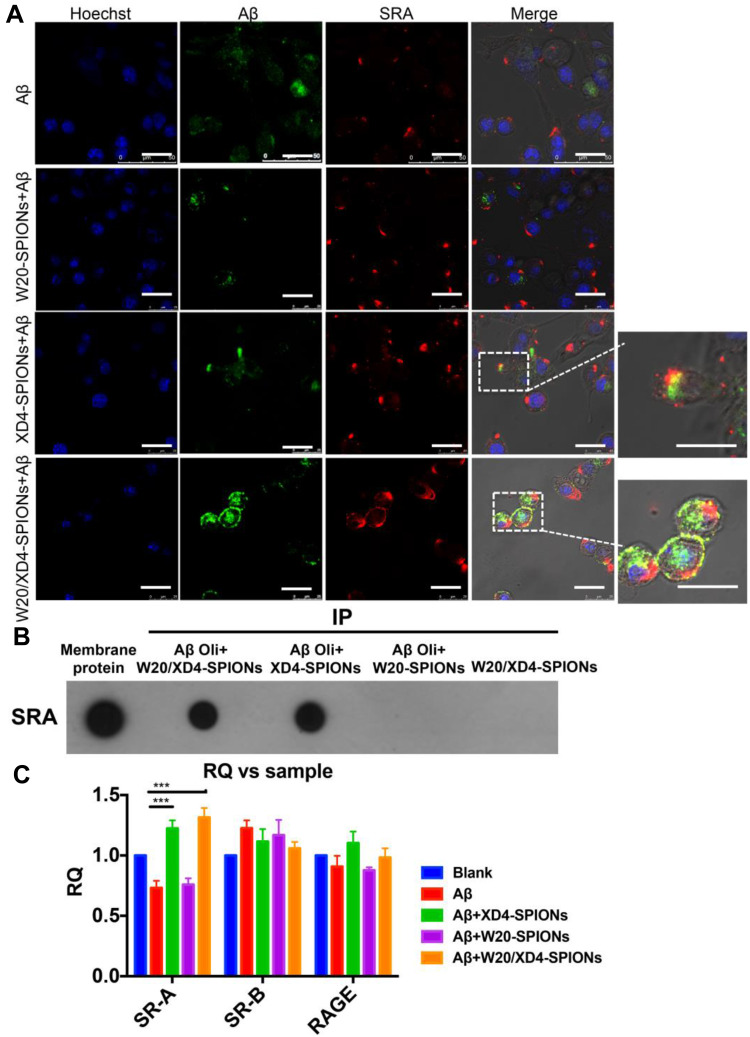

Figure 4.

W20/XD4-SPIONs-mediated AβOs phagocytosis by BV-2 cells via SR-A. (A) FITC-AβOs (green) were pre-incubated with XD4-SPIONs, W20-SPIONs or W20/XD4-SPIONs for 1 h, and then added to BV-2 cells. After 1.5 h of incubation, BV-2 cells were immunolabeled with anti-SR-A antibody (red) and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 25 μm. (B) The membrane extracts of BV-2 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with W20-, XD4- or W20/XD4-SPIONs in the presence or absence of AβOs. The immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by immunoblotted with anti-SR-A antibody. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the mRNA levels of SR-A, SR-B and RAGE in BV-2 cells pre-incubated with W20-, XD4- or W20/XD4-SPIONs in the presence or absence of AβOs. Data represent means ± SEM. ***P < 0.001.

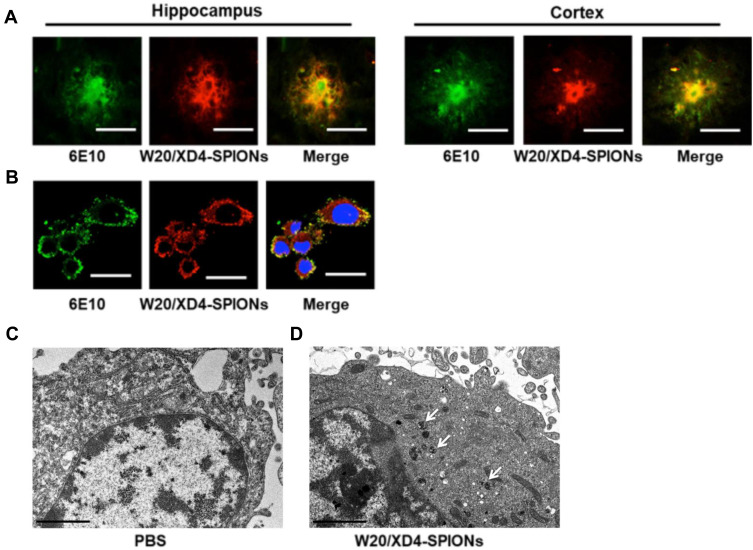

W20/XD4-SPIONs Specifically Recognized AβOs in AD Brains

To investigate whether W20/XD4-SPIONs could recognize AβOs in AD mouse brains, the hippocampus and cortex of AD mouse brains were double-stained by 6E10 antibody and W20/XD4-SPIONs. We observed the immunofluorescence of 6E10-staining was overlaid by W20/XD4-SPIONs staining (Figure 2A), indicating that AβOs existed in all types of Aβ plaques and were specially recognized by W20/XD4-SPIONs, which established their potential as an Aβ oligomer-targeting MRI probe to detect pathological regions in AD brains.

Figure 2.

W20/XD4-SPIONs specifically recognized AβOs. (A) The brain sections of AD mice were probed with W20/XD4-SPIONs (red) and 6E10 antibody against Aβ (green) and imaged. Scale bar, 25 μm. (B) BV-2 cells were exposed to AβOs and W20/XD4-SPIONs for 12 h, immunolabeled with anti-Aβ (6E10, green) and anti-c-myc (W20/XD4-SPIONs, red) antibodies and then analyzed by confocal microscopy. Hoechst, blue. Scale bar, 25 μm. (C–D) BV-2 cells were incubated with or without W20/XD4-SPIONs for 4 h at 37°C, and the intracellular distribution of W20/XD4-SPIONs was detected in an ultrathin section of cells via TEM. Scale bar, 2 μm. (C) Representative images of BV-2 cells treated with PBS only. (D) Representative images of BV-2 cells incubated with W20/XD4-SPIONs, which were present in the cytoplasm (arrow).

W20/XD4-SPIONs Promoted AβOs Phagocytosis by BV-2 Cells via SR-A

In order to promote the phagocytosis of AβOs by microglia, a peptide XD4 that can enhance glial uptake of AβOs by activating SR-A was introduced to SPIONs.25 To validate the internalization of AβOs and W20/XD4-SPIONs in BV-2 cells, their distribution pattern was detected by immunofluorescence of Aβ (stained using 6E10 antibody) and W20/XD4-SPIONs (stained using anti-c-myc antibody), respectively. We observed the fluorescence signal of AβOs colocalized with W20/XD4-SPIONs in the cells (Figure 2B), suggesting that extracellular AβOs may be recognized by W20/XD4-SPIONs and phagocyted by BV-2 cells as a part of the complex. Then, the intracellular distribution of W20/XD4-SPIONs was detected by TEM (Figure 2C and D). We observed that W20/XD4-SPIONs located in the cytoplasm of the BV-2 cells (Figure 2D), confirming the phagocytosis of W20/XD4-SPIONs by BV-2 cells.

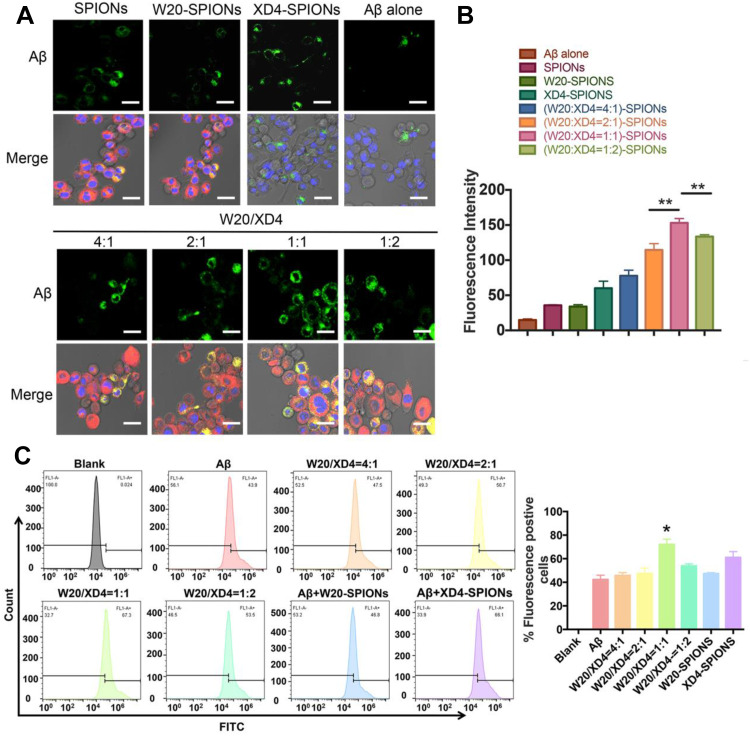

To optimize the ratio of W20 and XD4 on SPIONs, BV-2 cells were further incubated with FITC-AβOs and SPIONs conjugated with different molecular ratios of W20 and XD4 for 1.5 h, and the fluorescence of internalized AβOs was measured (Figure 3A). Consistent with the enhanced uptake mediated by XD4, the SPIONs conjugated with XD4 significantly enhanced intracellular levels of AβOs. Interestingly, the SPIONs simultaneously conjugated with both W20 and XD4 further increased AβO internalization compared with XD4-SPIONs. The molecular ratio of W20 and XD4 at 1:1 resulted in the highest AβOs phagocytic activity (Figure 3B), which was also confirmed by flow cytometry analysis (Figure 3C), and we applied this ratio in the subsequent experiments.

Figure 3.

W20/XD4-SPIONs promoted AβOs phagocytosis by BV-2 cells. (A) BV-2 cells were incubated with FITC-AβOs and SPIONs conjugated with different molecular ratios of W20 and XD4 for 1.5 h, and the internalized FITC-AβOs (green) and W20/XD4-SPIONs (c-myc-tag, red) were imaged. Hoechst, blue. Scale bar, 25 μm. (B) Quantitative immunofluorescence analysis of AβOs signal in BV-2 cells. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of the internalized FITC-AβOs in BV-2 cells. Quantitative immunofluorescence analysis of AβOs signal in BV-2 cells treated with different kinds of nanoparticles. Data represent means ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

To verify whether the increased AβO uptake was mediated by SR-A, the fluorescence of FITC-AβOs and SR-A (stained using anti-SR-A antibody) in BV-2 cells was determined. The high intracellular co-localization of AβOs with SR-A was observed by W20/XD4-SPIONs or XD4-SPIONs incubation, while less co-localization was observed when incubated with W20-SPIONs (Figure 4A). Consistently, the immunoprecipitation of SR-A from BV-2 cells incubated together with W20/XD4-, XD4- or W20-SPIONs in the presence of AβOs further confirmed that SR-A was involved in the enhanced uptake of AβOs by W20/XD4-SPIONs or XD4-SPIONs, but not W20-SPIONs (Figure 4B). Moreover, SR-A expression was significantly increased when BV-2 cells were incubated with W20/XD4-SPIONs or XD4-SPIONs, while there was no statistical change in the gene expression of other microglial cell surface receptors, such as SR-B and RAGE (Figure 4C).

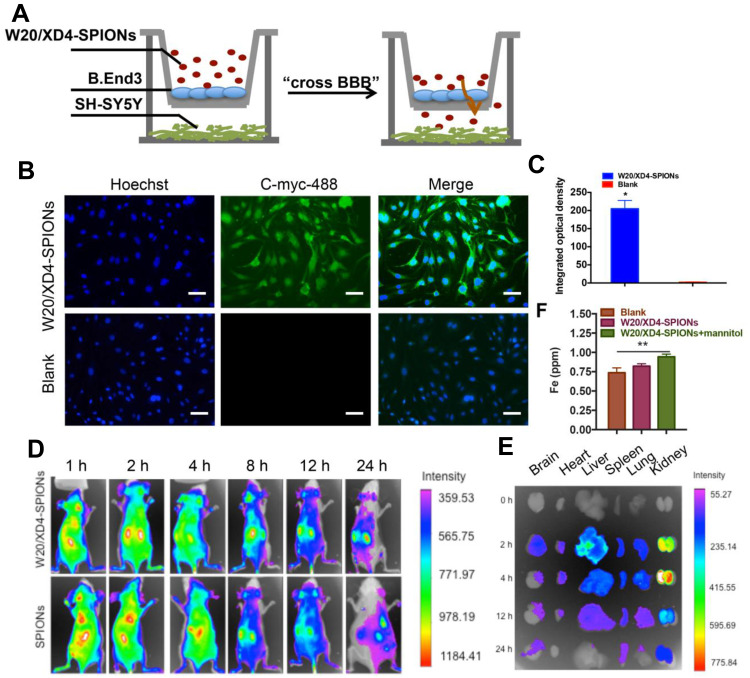

W20/XD4-SPIONs Penetrated the Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB)

A co-culture transwell model was used to determine the in vivo BBB permeability of W20/XD4-SPIONs (Figure 5A). W20/XD4-SPIONs displayed significant fluorescence signal in recipient SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 5B and C), indicating that W20/XD4-SPIONs crossed the monolayer of b. End 3 cells and reached the recipient SH-SY5Y cells, which may be effective agents with BBB permeability. For the in vivo bio-distribution of W20/XD4-SPIONs, nude mice were intravenously administrated with Cy7-labeled SPIONs and the Cy7 fluorescence was then detected. We observed the Cy7 fluorescence of the SPIONs in mice changed time-dependently. The presence of all the SPIONs throughout the mouse body at 1 h post injection, and then slowly accumulated in brain, lungs, liver and kidneys, while they were mostly located within the liver at 8 h post-injection (Figure 5D). The organs were collected at 0, 2, 4, 12, 24 h post injection, and their Cy7 fluorescence was measured (Figure 5E). More W20/XD4-SPIONs accumulated in the organs, especially in brains (Figure 5E), suggesting that W20/XD4-SPIONs may readily penetrate BBB and exist in the brains for a longer time. Moreover, Iron content in the brain lysates was determined by ICP. Approximately 1.0% of W20/XD4-SPIONs penetrated the brain when injected together with mannitol (Figure 5F). No apparent difference in the iron content was observed in mice injected by unconjugated-SPIONs and conjugated-SPIONs together with mannitol, but the iron contents in the brains of SPIONs-treated mice were higher than vehicle-treated mice (Figure S3). We further performed Prussian blue staining in the hippocampus area of AD mice treated with or without W20/XD4-SPIONs 12 h later. The significant hemosiderin-positive area was observed in W20/XD4-SPIONs-treated AD mice relative to vehicle-treated ones, suggesting W20/XD4-SPIONs can penetrate the BBB and especially target AβOs area in the brain (Figure S4).

Figure 5.

W20/XD4-SPIONs penetrated the blood–brain barrier. (A) The schematic illustration of in vitro BBB transwell system. (B) b. End 3 cells were incubated with W20/XD4-SPIONs for 4 h at 37°C, and their uptake in SH-SY5Y cells (recipients) was detected by anti-c-myc antibody followed by corresponding secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488. Scale bar, 25 μm. (C) Quantitative immunofluorescence analysis of W20/XD4-SPIONs’ signal in SH-SY5Y cells. (D) BALB/c mice were intravenously injected with Cy7-labeled SPIONs conjugated with or without W20/XD4 via tail vein. The fluorescence was detected using IVIS spectrum imaging system. (E) The organs of mice, including brain, heart, liver, spleen, lungs and kidneys were collected at 0, 2, 4, 12, 24 h post-injection, the fluorescence intensity was detected using IVIS spectrum imaging system. (F) Fe content in the brain lysate of BALB/c mice intravenously injected with W20/XD4-SPIONs with or without mannitol was determined by inductively coupled plasma spectrometry (ICP). *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

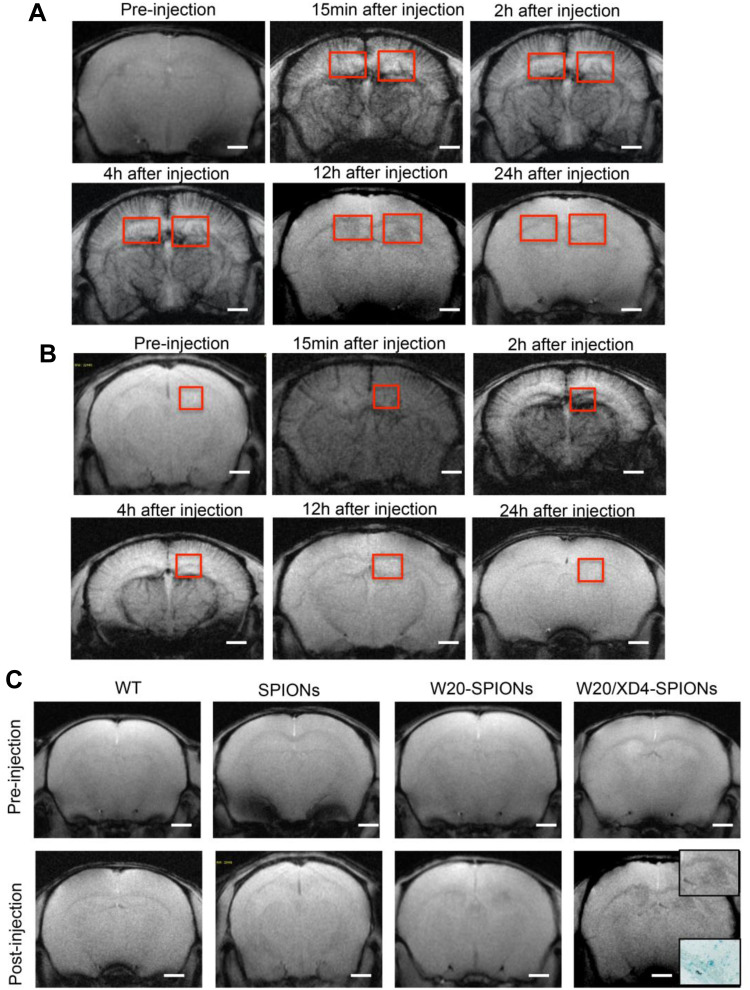

W20/XD4-SPIONs Exhibited Remarkable MR Signal in AD Mouse Brains

To detect whether W20/XD4-SPIONs offered sufficiently intensive MR contrast to AβOs in mouse brains, WT and AD mice were injected with W20/XD4-SPIONs via tail vein and allowed to recover for 15 min before MRI. The probe distributions in the brains of AD (Figure 6A) and WT mice (Figure 6B) were detected by MRI at 15 min, 2, 4, 12 and 24 h post-injection. The images from AD mice rather than WT mice gradually showed clear signals in the hippocampus in a time-dependent manner, and they showed the highest relative signal at 12 h after injection. Therefore, this time point was chosen to catch the MR images of SPIONs in AD and WT mice. The results showed that W20/XD4-SPIONs brought much more pronounced MR signals in AD brains than W20-SPIONs, while no MR signal was detected in the brains of both WT mice and AD mice injected with unconjugated-SPIONs (Figure 6C). Consistently, Prussian blue staining in the hippocampus area confirmed the presence of the probe. Overall, our data showed that W20/XD4-SPIONs gained access to the hippocampus and provided a strong MR signal to sensitively distinguish AD mice from WT controls.

Figure 6.

W20/XD4-SPIONs exhibited remarkable MR signal in AD mouse brains. (A and B) In vivo T2*-weighted images of W20/XD4-SPIONs distribution in AD (A) and WT (B) mouse brains were captured pre- and 15 min, 2 h, 4 h, 12 h and 24 h post intravenous injection of W20/XD4-SPIONs. (C) In vivo T2*-weighted images of the probe distribution in AD mouse brains after intravenous injection of W20/XD4-SPIONs, W20-SPIONs and SPIONs. Boxed regions are shown at higher magnification or stained by the Prussian blue. Scale bar, 1 mm.

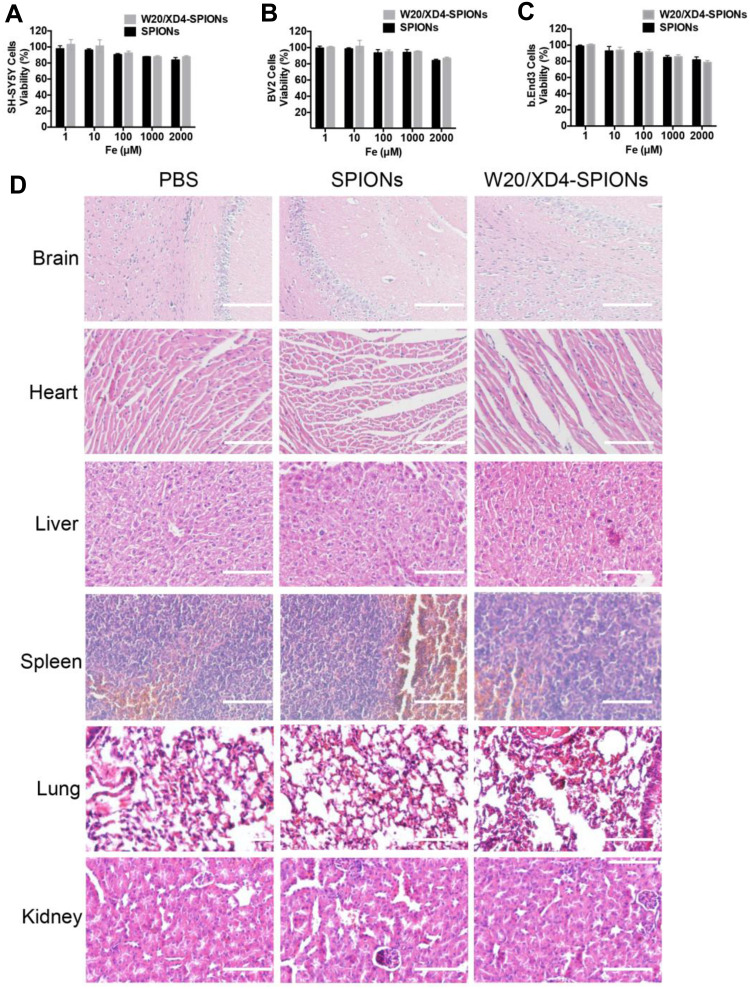

W20/XD4-SPIONs Did Not Show Evident Toxicity

W20/XD4-SPIONs were incubated with three different mammalian cell lines including SH-SY5Y, BV-2 and b. End 3 cells and the cell viability were measured. No change of the cell viability was observed after 48 h incubation with W20/XD4-SPIONs even at a relatively high concentration (2000 μM Fe3+) (Figure 7A–C). Importantly, the signs of infection or distress of mice were monitored for 7 days after treatment with 400 mg/kg of W20/XD4-SPIONs or unconjugated-SPIONs. No side effects were detected. Furthermore, H&E staining demonstrated that there was not any morphological change in the organs (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

No evident cytotoxicity was detected with W20/XD4-SPIONs. SH-SY5Y cells (A), BV-2 cells (B), and b. End 3 cells (C) were incubated with unconjugated-SPIONs or W20/XD4-SPIONs for 48 h at 37°C. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. (D) No potential toxicity of W20/XD4-SPIONs was detected in various organs of mice by H&E staining. C57BL/6 mice were intravenously injected with unconjugated-SPIONs or W20/XD4-SPIONs at 400 mg/kg, sacrificed and the organs were harvested at 7 days after the injection. The sections of brain, heart, liver, spleen, lungs and kidneys were stained with H&E. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Discussion

Many promising preclinical results have repeatedly failed in the clinical trials for AD. One of the suspected reasons for this failure was late time for intervention. Early diagnostics before symptoms arise would facilitate earlier intervention and delay AD progression. However, few early diagnostic methods have been applied to clinic except the Rating Scale and PET for the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment.8 Thus, powerful diagnostic methods for the early-stage of AD are urgently needed. As AβOs rather than Aβ monomers and fibrils correlate well with AD dementia,12,17 the approaches targeting AβOs would have a promising application in the diagnosis of AD. Among all the diagnostic strategies for AD, non-invasive diagnostic methods are more acceptable, especially at early stage, although collected CSF often shows more accurate results.9 MRI as a non-invasive, low-cost and non-radioactive imaging modality has been widely used to detect the brain structure and connection of AD patients.26 Although AβOs are attracting targets for MRI diagnosis, an MRI molecular probe with sensitivity, specificity and high-affinity for detecting AβOs needs to be developed. Our present work used AβO-specific antibody W2027,28 and microglial SR-A activator XD4 to construct novel multifunctional nanoparticles W20/XD4-SPIONs. The obtained nanoparticles retained the specific binding of W20 to AβOs, recognized AD-causing toxic oligomers in brains, and promoted AβOs by microglia.

Over-production or clearance deficiency breaks Aβ homeostasis and induces Aβ accumulation, which strongly contributes to the pathogenesis of AD.29 Microglia, the innate immune cells in the brain, are responsible for the phagocytosis and clearance of toxic AβOs, which prevent the development of AD.30 However, with AD progression, microglia are overactivated and lose their protective functions, leading to Aβ aggregation, which simultaneously release proinflammatory factors and exacerbate tau pathology, resulting in neuron injury and cognitive deficits.31,32 Multiple cell surface receptors of microglia, including SR-A,33–35 SR-BI, CD36,36 CD14, CD47 and RAGE (receptor for advanced glycation end-products)37 are involved in Aβ uptake and degradation. SR-A activation is a useful strategy for Aβ clearance and AD treatment.38 Previously, we have reported the heptapeptide XD4 enhanced AβOs phagocytosis by microglia through increasing AβOs and SR-A binding. XD4 attenuated AβOs-induced cytotoxicity and decreased the levels of proinflammatory cytokines.25 In the present study, we introduced XD4 peptide to the SPIONs, the data demonstrated that the resultant W20/XD4-SPIONs retained XD4 property for SR-A activation, significantly promoted microglial uptake of Aβ.

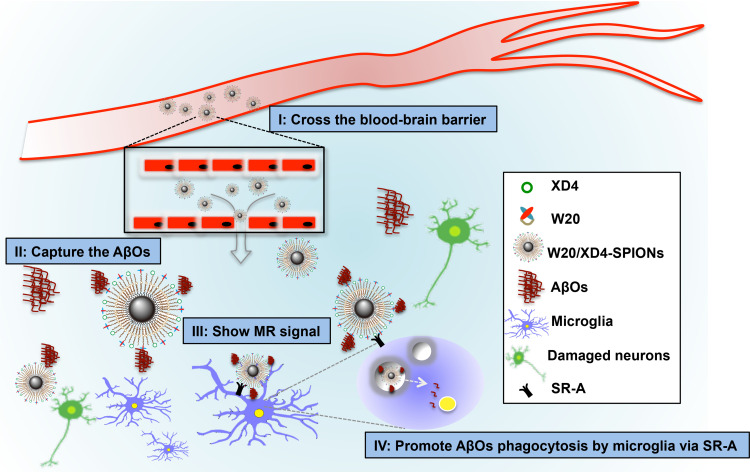

SPIONs have many advantages such as good biocompatibility, excellent MRI contrast, function stability and small size.39–41 Ultra-small SPIONs may cross BBB to target specific markers for disease diagnosis via MRI. Our W20/XD4-SPIONs with a diameter of around 11.5 nm, effectively passed BBB when intravenously injected together with 15% mannitol, and showed the strongest signal in the hippocampus of AD mice 12 h after injection. Hippocampus is vulnerable to AβOs. AβOs readily bind to hippocampal synapses,16,42 which attract W20/XD4-SPIONs to gather to the hippocampus. W20/XD4-SPIONs thus exhibit strong MR signal, differentiating AD mice from WT controls (Scheme 1). Moreover, XD4 on the SPIONs increased microglial phagocytosis of W20/XD4-SPIONs combining with AβOs, leading to the destruction of the nanoparticles and decreased MR signal. Finally, signal generation and depletion reached balance 12 h post-injection.

Scheme 1.

Schematic interpretation of W20/XD4-SPIONs in vivo. (I) W20/XD4-SPIONs penetrated the blood–brain barrier. (II) W20/XD4-SPIONs specifically detected AβOs in the brains of AD mice. (III) W20/XD4-SPIONs exhibited significant magnetic resonance signal in the brains of AD mice. (IV) W20/XD4-SPIONs promoted AβOs phagocytosis by microglia via SR-A.

In summary, our multifunctional nanoparticles W20/XD4-SPIONs could cross BBB to reach the oligomer area in brain, distinguishing AD mice from WT mice, exhibiting early diagnostic potentials for AD. Besides the potential application in AD diagnosis, W20/XD4-SPIONs contain both W20 and XD4, possess dual therapeutic function, this kind of nanoparticles is likely to be the most effective for AD mice relative to W20- or XD4-SPIONs. Future studies will be conducted to investigate its potential therapeutic effects on AD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81971610).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Drew L. An age-old story of dementia. Nature. 2018;559(7715):S2–S3. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05718-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long JM, Holtzman DM. Alzheimer disease: an update on pathobiology and treatment strategies. Cell. 2019;179(2):312–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Georganopoulou DG, Chang L, Nam JM, et al. Nanoparticle-based detection in cerebral spinal fluid of a soluble pathogenic biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(7):2273–2276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409336102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toledo JB, Xie SX, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM. Longitudinal change in CSF Tau and Abeta biomarkers for up to 48 months in ADNI. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(5):659–670. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1151-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slemmon JR, Meredith J, Guss V, et al. Measurement of Aβ1-42 in cerebrospinal fluid is influenced by matrix effects. J Neurochem. 2012;120(2):325–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07553.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Okamura N, Furumoto S, et al. 18F-THK523: a novel in vivo tau imaging ligand for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 4):1089–1100. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jack CR Jr., Wiste HJ, Vemuri P, et al. Brain beta-amyloid measures and magnetic resonance imaging atrophy both predict time-to-progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2010;133(11):3336–3348. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolgin E. Alzheimer’s disease is getting easier to spot. Nature. 2018;559(7715):S10–S12. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05721-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hane FT, Robinson M, Lee BY, Bai O, Leonenko Z, Albert MS. Recent progress in alzheimer’s disease research, Part 3: diagnosis and treatment. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017;57(3):645–665. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodson R. Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2018;559(7715):S1. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05717-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane CA, Hardy J, Schott JM. Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(1):59–70. doi: 10.1111/ene.13439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cline EN, Bicca MA, Viola KL, Klein WL. The amyloid-beta oligomer hypothesis: beginning of the third decade. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018;64(s1):S567–S610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zempel H, Thies E, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Abeta oligomers cause localized Ca(2+) elevation, missorting of endogenous Tau into dendrites, Tau phosphorylation, and destruction of microtubules and spines. J Neurosci. 2010;30(36):11938–11950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2357-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poon WW, Blurton-Jones M, Tu CH, et al. beta-Amyloid impairs axonal BDNF retrograde trafficking. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(5):821–833. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pigino G, Morfini G, Atagi Y, et al. Disruption of fast axonal transport is a pathogenic mechanism for intraneuronal amyloid beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(14):5907–5912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901229106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong S, Beja-Glasser VF, Nfonoyim BM, et al. Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science. 2016;352(6286):712–716. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8(6):595–608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viola KL, Klein WL. Amyloid beta oligomers in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis, treatment, and diagnosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(2):183–206. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1386-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos LE, Ferreira ST. Crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress and brain inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology. 2018;136(Pt B):350–360. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forloni G, Balducci C. Alzheimer’s disease, oligomers, and inflammation. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018;62(3):1261–1276. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Chang L, et al. Synaptic targeting by Alzheimer’s-related amyloid beta oligomers. J Neurosci. 2004;24(45):10191–10200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):795–804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perrin RJ, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM. Multimodal techniques for diagnosis and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2009;461(7266):916–922. doi: 10.1038/nature08538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu XG, Lu S, Liu DQ, et al. ScFv-conjugated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for MRI-based diagnosis in transgenic mouse models of Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases. Brain Res. 2019;1707:141–153. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Su YJ, Zhou WW, et al. Activated scavenger receptor A promotes glial internalization of abeta. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitwell JL. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging. Curr Opin Neurol. 2018;31(4):396–404. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Zhang J-H, Wang Y-J, et al. Conformation-dependent single-chain variable fragment antibodies specifically recognize beta-amyloid oligomers. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(3):579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Sun XX, Xue D, et al. Conformation-dependent scFv antibodies specifically recognize the oligomers assembled from various amyloids and show colocalization of amyloid fibrils with oligomers in patients with amyloidoses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814(12):1703–1712. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reiss AB, Arain HA, Stecker MM, Siegart NM, Kasselman LJ. Amyloid toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Rev Neurosci. 2018;29(6):613–627. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2017-0063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hansen DV, Hanson JE, Sheng M. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Biol. 2018;217(2):459–472. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201709069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarlus H, Heneka MT. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(9):3240–3249. doi: 10.1172/JCI90606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salter MW, Stevens B. Microglia emerge as central players in brain disease. Nat Med. 2017;23(9):1018–1027. doi: 10.1038/nm.4397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Husemann J, Loike JD, Anankov R, Febbraio M, Silverstein SC. Scavenger receptors in neurobiology and neuropathology: their role on microglia and other cells of the nervous system. Glia. 2002;40(2):195–205. doi: 10.1002/glia.10148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bamberger ME, Harris ME, McDonald DR, Husemann J, Landreth GE. A cell surface receptor complex for fibrillar beta-amyloid mediates microglial activation. J Neurosci. 2003;23(7):2665–2674. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02665.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alarcon R, Fuenzalida C, Santibanez M, von Bernhardi R. Expression of scavenger receptors in glial cells. Comparing the adhesion of astrocytes and microglia from neonatal rats to surface-bound beta-amyloid. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(34):30406–30415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414686200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stuart LM, Bell SA, Stewart CR, et al. CD36 signals to the actin cytoskeleton and regulates microglial migration via a p130Cas complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(37):27392–27401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702887200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilkinson K, El Khoury J. Microglial scavenger receptors and their roles in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:489456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canton J, Neculai D, Grinstein S. Scavenger receptors in homeostasis and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(9):621–634. doi: 10.1038/nri3515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viola KL, Sbarboro J, Sureka R, et al. Towards non-invasive diagnostic imaging of early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Nanotechnol. 2015;10(1):91–98. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De M, Chou SS, Joshi HM, Dravid VP. Hybrid magnetic nanostructures (MNS) for magnetic resonance imaging applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63(14–15):1282–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei H, Bruns OT, Kaul MG, et al. Exceedingly small iron oxide nanoparticles as positive MRI contrast agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(9):2325–2330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620145114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puzzo D. Abeta oligomers: role at the synapse. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(4):1077–1078. doi: 10.18632/aging.101818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]