Abstract

Introduction:

Bivalirudin and heparin are the two most commonly used anticoagulants used during Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI). The results of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) comparing bivalirudin versus heparin monotherapy in the era of radial access are controversial, questioning the positive impact of bivalirudin on bleeding. The purpose of this systematic review is to summarize the results of RCTs comparing the efficacy and safety of bivalirudin versus heparin with or without Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitors (GPI).

Methods:

This systematic review was performed in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses PRISMA statements for reporting systematic reviews. We searched the National Library of Medicine PubMed, Clinicaltrial.gov and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to include clinical studies comparing bivalirudin with heparin in patients undergoing PCI. Sixteen studies met inclusion criteria and were reviewed for the summary.

Findings:

Several RCTs and meta-analyses have demonstrated the superiority of bivalirudin over heparin plus routine GPI use in terms of preventing bleeding complications but at the expense of increased risk of ischemic complications such as stent thrombosis. The hypothesis of post- PCI bivalirudin infusion to mitigate the risk of acute stent thrombosis has been tested in various RCTs with conflicting results. In comparison, heparin offers the advantage of having a reversible agent, of lower cost and reduced incidence of ischemic complications.

Conclusion:

Bivalirudin demonstrates its superiority over heparin plus GPI with better clinical outcomes in terms of less bleeding complications, thus making it as anticoagulation of choice particularly in patients at high risk of bleeding. Further studies are warranted for head to head comparison of bivalirudin to heparin monotherapy to establish an optimal heparin dosing regimen and post-PCI bivalirudin infusion to affirm its beneficial effect in reducing acute stent thrombosis.

Keywords: Heparin, bivalirudin, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, percutaneous coronary intervention, bleeding events, stent thrombosis

1. INTRODUCTION

The ideal antithrombotic agent for patients undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) remains controversial. As thrombin plays a pivotal role in the formation of a stable thrombus, the use of antithrombotic medications are an integral part of standard therapy in patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS). Heparin and bivalirudin are currently the most commonly used antithrombotic agents in patients with ACS [1, 2]. The use of either agent is a Class I recommendation in patients undergoing PCI [3]. The efficacy of these agents, however, also needs to be balanced by their safety in terms of risk of bleeding, as the major bleeding is associated with increased morbidity and mortality [4]. Several Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses have been performed comparing the efficacy and safety of heparin combined with the potent antiplatelet effect of a Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitor (GPI) with bivalirudin [5-7]. Despite possessing several potential advantages such as a short half-life with low risk of bleeding, linear kinetics and low immunogenic potential, the superiority of bivalirudin over heparin is still debated. The purpose of this review is to summarize the results of major RCTs comparing the efficacy of bivalirudin and heparin with or without GPI.

2. METHODS

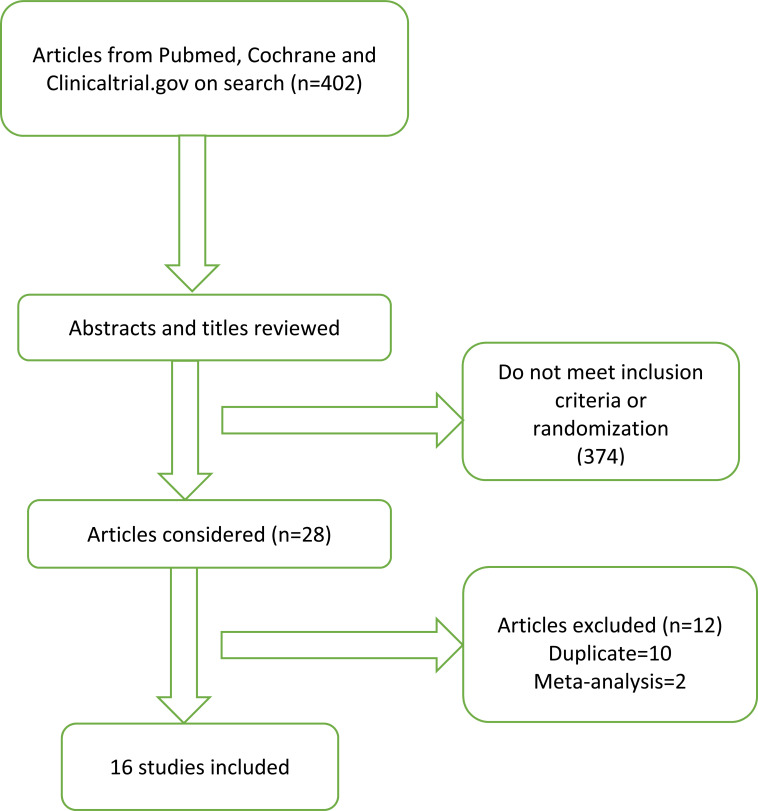

This systematic review was performed in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statements for reporting systematic reviews [8]. We searched the National Library of Medicine PubMed, Clinicaltrial.gov and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to include clinical studies comparing bivalirudin with heparin in ACS patients. Studies conducted during the period of January 2000 through April 2018 were included. The keywords used to search studies were “bivalirudin”, “heparin”, “ST-elevation myocardial infarction”, “acute coronary syndrome”, “ACS”, “percutaneous coronary intervention” and “randomized controlled trials”. In addition to the computerized search, we manually reviewed the reference lists and related articles of all retrieved studies to complete the search. Two independent authors (SB and HBP) reviewed all titles from the search results and the articles selected for review. The selection process is outlined in Fig. 1.

Fig. (1).

Search algorithm.

Studies with the following inclusion criteria were included in this systematic review: (1) randomized controlled trial, (2) comparison of bivalirudin with heparin in the setting of ACS, (3) published in English. The outcomes of interest were major adverse cardiac events (MACE) [all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), urgent target vessel revascularization (TVR), stroke and major bleeding]. Relevant data from the trials, including authors, year, design, sample size, follow-up duration, patient characteristics, and the main results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the study designs, patient characteristics, and outcomes.

|

Study Name

and Year |

Trial Design

Comparison Group and Inferiority or Superiority Margins |

Patient Characteristics | Procedure Type and Reason for PCI | Sample Size (n) | GPI Usage with Bivali and Heparin, Respectively | Dose of Bivali | Dose of Heparin | ACT Cut-off | Primary Outcome and Follow-up Duration | Results of Primary Outcome of Bivali as Compared to Heparin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VALIDATE-SWEDEHEART (2017) |

Multicenter, RCT Bivali vs heparin Superiority |

Age: 68 (Median) Gender: M (73.4%), F (26.6%) DM: 16.6% CKD: NA HTN: 51.7% HLP: 31.5 Previous Stroke: 4% Prior MI:16.2% Prior CABG: 4.9% |

PCI Reason for PCI: STEMI/NSTEMI |

6006 | Bailout GPI 2.4% and 2.8% | 0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 70-100U/kg | ≥250 secs | Composite of all-cause mortality, MI or major bleeding 180 days |

Non-inferior |

| MATRIX (2015) | Multicenter, RCT Bivali vs UFH Superiority |

Age: 65.4 ± 11.9 (Mean) Sex: M (76.2%), F (23.8%) DM: 22.2% CKD: 1.3% HTN: 62.2% HLP: 43.7 Prior Stroke: 5.0% Prior MI: 14.3% Prior CABG: 3.0% |

PCI Reason for PCI: STEMI/NSTEMI |

7213 | GPI (4.6%)* and (25.9%)# | 0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 70-100U/kg (without GPI) and 50-70U/kg (with GPI) | NA | MACE (composite of death, MI or stroke) and NACE (composite of major bleeding or MACE) 30 days |

Non-inferior |

| Naples III (2015) | Single center, RCT Bivali vs UFH Superiority |

Age: 78 ± 4 (Mean) Sex: M (52.5%), F (47.5%) DM: 44% CKD: 45.7% (<30 ml/min/1.73 m2 patients were not included) HTN: 83.5% HLP: 56.5 Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI: 40% Prior CABG: 13.4% |

Elective trans-femoral PCI in high bleeding risk patients Reason for PCI: Stable/unstable angina pectoris (with negative biomarkers) |

837 | Tirofiban# 0.5% and 1.3% | 0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 70U/kg | ≥250 secs | Major bleeding 30 days and 1 year |

Non-inferior |

| BRIGHT (2015) | Multicenter, RCT Bivali vs heparin alone vs heparin plus tirofiban Superiority |

Age: 57.8 ± 11.7 (Mean) Sex: M (82.1%), F (17.9%) DM: 21.2% CKD: 10.9% HTN: 42.1% HLP: 37.1 Prior Stroke: 8.1% Prior MI: 4.4% Prior CABG: NA |

Emergent PCI Reason for PCI: STEMI, NSTEMI |

2194 | Bivali- Tirofiban (4.4%)*, Heparin-Heparin alone (n=729) (5.6%)*, Heparin plus tirofiban (n=730) |

0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h, additional median 3-hour Post procedural dose infusion of bivali | 100U/kg (without tirofiban) and 60 U/kg (with tirofiban) | ≥225 secs | NACE (composite of all-cause death, reinfarction, TVR, or stroke) or bleeding 30 days and 1 year |

Superior in reducing NACE with post-PCI infusion in bivalirudin group |

| EUROMAX trial (2014) | RCT Bivali vs heparin plus routine GPI vs heparin plus bailout GPI Superiority |

Age: 61 (Median) Sex: M (76.7%), F (23.3%) DM: 14.2% CKD: 16.6% HTN: 45.1% HLP: 37.7% Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI: 9.2% Prior CABG: 2.4% |

Primary PCI Reason for PCI: STEMI |

2198 | Bivali- GPI 3.9% (protocol deviation) 7.9% (bailout), Heparin- Routine GPI (n=649) and bailout GPI (n=117) |

0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 100U/kg (without GPI) and 60 U/kg (with GPI) | NA | Composite of death or major bleeding 30 days |

Bivalirudin is superior in reducing major bleeding but increases stent thrombosis risk |

| HEAT- PPCI (2014) | Single center, RCT Bivali vs UFH Equivalent |

Age: 63.2 (Mean) Sex: M (72%), F (28%) DM:14% CKD: NA HTN: 41.5% HLP: 37.5 Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI:12% Prior CABG: 2% |

Primary PCI Reason for PCI: STEMI |

1812 | Bailout abciximab 13% and 15% | 0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 70U/kg | ≥200 secs for heparin and ≥225 secs for bivali | MACE (composite of all-cause mortality, CVA, reinfarction, TVR) and major bleeding 28 days |

Bivalirudin is inferior in reducing risk of MACE and stent thrombosis events |

| ARMYDA-7 BIVALVE (2012) | Multicenter, RCT Bivali vs UFH Superiority |

Age: 70.2 ± 9 (Mean) Sex: M (71.5%), F (28.5%) DM: 63% CKD: 21% HTN: 90.5% HLP: NA Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI: 35.5% Prior CABG: NA |

High risk PCI Reason for PCI: NSTEMI/UA/Stable angina pectoris |

401 | GPI#* 12% and 14% | 0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 75U/kg | NA | MACE (cardiac death, MI, stent thrombosis, TVR) or any bleeding event 30 days |

Superior in reducing bleeding events |

| ISAR-REACT 4 (2011) | Multicenter, RCT Bivali vs UFH plus Abciximab Superiority |

Age: 67.5 ± 11 (Mean) Sex: M (76.9%), F (23.1%) DM: 29% CKD: NA HTN: 85.5% HLP: 68.5 Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI: 20.4% Prior CABG: 10.5% |

PCI Reason for PCI: UA/NSTEMI |

1721 | None and Abciximab | 0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 70U/kg | NA | Composite of death, large recurrent MI, urgent TVR, or major bleeding 30 days |

Bivalirudin is superior in reducing bleeding events |

| NAPLES (2009) | RCT Bivali vs UFH plus Tirofiban |

Age: 65.3 ± 9 (Mean) Sex: M (65.1%), F (34.9%) DM: 100% CKD: 37.7% HTN: 76.4% HLP: 63.9 Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI: 44.7% Prior CABG: 8.0% |

Elective PCI in diabetic patients Reason for PCI: UA/Stable angina pectoris/asymptomatic |

335 | None and Tirofiban | 0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 70U/kg | ≥250 secs | Composite of death, MI, urgent TVR, or in hospital bleeding 30 days |

Bivalirudin is superior in reducing composite of death, MI, urgent TVR and in hospital minor bleeding |

| HORIZONS-AMI (2009) | Multicenter, RCT Bivali vs Heparin plus GPI Non-inferiority and superiority |

Age: 60.2 (Mean) Sex: M (76.5%), F (23.5%) DM: 16.5% CKD: 16.5% HTN: 53.5% HLP: 43% Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI: 10.5% Prior CABG: 3.0% |

PCI Reason for PCI: STEMI |

3602 | Abciximab, Eptifibatide (7.5%)* and Abciximab, Eptifibatide | 0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 60U/kg | ≥200-250 secs | NACE (MACE or major bleeding); MACE (composite of death, MI, TVR or stroke) 30 days,1 year and 3 year |

Bivalirudin is superior in reducing all-cause mortality, re-infarction and major bleeding |

| ISAR- REACT 3 (2008) | RCT Superiority Bivali vs UFH |

Age: 66.9 ± 10 (Mean) Sex: M (76.5%), F (23.5%) DM: 27.4% CKD: NA HTN: 89.2% HLP: 79.7 Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI: 31.1% Prior CABG: 11.7% |

PCI Reason for PCI: Stable/Unstable angina |

4570 | None | 0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 140U/kg bolus infusion followed by placebo infusion; except at one center 100U/kg | ≥250 secs only at one center |

NACE (composite of death, large recurrent MI, urgent TVR, or major bleeding) 30 days |

Bivalirudin is non-inferior in reducing NACE but did decrease incidence of major bleeding |

| POTECT-TIMI-30 (2006) | RCT Bivali vs UFH plus eptifibatide vs enoxaparin plus eptifibatide Superiority |

Age: 59.8 ± 10.4 (Mean) Sex: M (67.1%), F (32.9%) DM: 40.4% CKD: NA HTN: 65.6% HLP: 55.3 Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI: 21.3% Prior CABG: 7% |

PCI Reason for PCI: NSTEMI |

857 | None and Eptifibatide | 0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 50 U/kg bolus (UFH) 0.5 mg/kg IV enoxaparin |

≥200-250 secs | Coronary flow reserve and major bleeding 24-48h |

Bivalirudin is superior in reducing minor bleeding, transfusion events and has greater coronary flow reserve |

| ACUITY (2006) | Multicenter, RCT Bivali alone vs bivali plus GPI vs UFH plus GPI Superiority |

Age: 63 (Mean) Sex: M (69.9%), F (30.1%) DM: 28.0% CKD: 19.1% HTN: 67.0% HLP: 57.2% Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI: 31.3% Prior CABG:17.9% |

PCI Reason for PCI: UA, NSTEMI |

13819 | Bivali-with GPI (4604), Without GPI (4612) Heparin- With GPI (4603) GPI used: (Abciximab, Eptifibatide) |

0.1mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 0.25mg/kg/h, increased to 1.75mg/kg/h during PCI | 60U/kg bolus with infusion of 12U/kg/h Enoxaparin: 1 mg/kg twice daily subcutaneously before angiography, with an additional 0.3-0.75mg/kg IV bolus before PCI |

≥200-250 secs | Composite of death, MI or repeat revascularization or major bleeding 30 days |

Bivalirudin is superior in reducing major bleeding events with similar rates of ischemia |

| REPLACE-1 (2004) | Multicenter, RCT Bivali plus GPI vs Heparin plus GPI |

Age: 64.3 ± 11.3 (Mean) Sex: M (69.9%), F (30.1%) DM: 30.1% HTN: 73.3% HLP: NA Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI: 41.5% Prior CABG: 23.3% |

Elective or urgent PCI | 1056 | GPI 71.1% and 72.5% GPI used: (Abciximab, Eptifibatide, Tirofiban) |

0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 60-70 U/kg bolus | ≥200-300 secs | Composite of death, MI or repeat revascularization or major bleeding 48h |

Non-inferior |

| REPLACE-2 (2003) | Multicenter, RCT Bivali plus bailout GPI vs Heparin plus planned GPI Non-inferiority |

Age: 62.6 (Mean) Sex: M (74.4%), F (25.6%) DM: 27.1% HTN: 67% HLP: NA Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI: 37.0% Prior CABG: 18.4% |

Elective or urgent PCI | 6010 | Bivali- GPI 7.2% bailout use* GPI (all cases) plus 5.2% bailout* GPI used: (Abciximab, Eptifibatide) |

0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h | 65U/kg bolus (with GPI) |

≥225 secs | Composite of death, MI or repeat revascularization or major bleeding 30 days |

Non-inferior in regards to prevent acute ischemic events and superior in preventing bleeding events. |

| CACHET (2002) | RCT Bivali with or without abciximab vs Heparin plus abciximab |

Age: 62.5± 11.3 (Mean) Sex: M (77.2%), F (22.8%) DM: NA HTN: NA HLP: NA Prior Stroke: NA Prior MI: NA Prior CABG: NA |

PCI | 268 | Abciximab (76% planned and 24% bailout) and Abciximab | Phase A: 1 mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 2.5mg/kg/h Phase B: 0.5mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h Phase C:0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/h |

70 U/kg bolus | ≥200 secs | Composite of death, myocardial infarction or repeat revascularization or major bleeding 7 days |

Non-inferior in reducing ischemic events |

#Operator’s discretion. *In cases of no reflow or thrombotic complications. Bivali: Bivalirudin; GPI: Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors; RCT: Randomized controlled trials; ACS: Acute coronary syndrome; STEMI: ST elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI: Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; UA: Unstable angina; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; MI: Myocardial Infarction; UFH: Unfractionated heparin; CKD: Chronic kidney disease; HTN: Hypertension; DM: Diabetes mellitus; M: Male; F: Female; HLP: Hyperlipidemia; CABG: Coronary artery bypass graft; TVR: Target vessel revascularization; NACE: Net adverse cardiac events; MACE: Major adverse cardiac events; NA: Not applicable; CVA: Cardiovascular accident.

3. DISCUSSION

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) is still the most commonly used anticoagulation agent [9]. Bivalirudin, a synthetic bivalent direct thrombin inhibitor, blocks fibrinogen recognition and catalytic sites, inhibiting both circulating and clot-bound thrombin [10-12]. It has favorable properties such as a short half-life and linear kinetics [11]. As it does not bind to plasma proteins and has low immunogenic potential, it is also used as an alternative anticoagulant for patients with suspected or confirmed heparin-induced thrombocytopenia [12]. However, despite these advantages, discrepancies exist for the superiority of bivalirudin over heparin.

3.1. Is Bivalirudin Plus Routine GPI Superior to Heparin Plus Routine GPI?

For decades, UFH was the anticoagulant of choice for PCI during ACS [13]. The use of bivalirudin as an anticoagulation agent was established based on the results of the BAT trial (Bivalirudin Angioplasty) [14], which showed that bivalirudin was associated with similar ischemic outcomes and a 62% relative reduction in major bleeding complications. As the trial was done in patients undergoing only balloon angioplasty without pretreatment with thienopyridines, the results are difficult to interpret in current practice. To test the feasibility of bivalirudin in patients undergoing coronary stenting along with the use of dual antiplatelet therapy, the CACHET (Comparison of Abciximab complications with Hirulog for Ischemic Events Trial) and REPLACE-1 (Randomized Evaluation of PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events-1) trials were conducted. Bailout or planned GPI use with bivalirudin versus heparin plus GPI was associated with lower rates of major bleeding with similar rates of ischemic events in CACHET trial [15]. The REPLACE-1 trial results showed an approximately 20% reduction in ischemic and bleeding complications with bivalirudin compared with heparin arm [10]. As these trials allowed the use of adjunctive GPI in either group at the discretion of the operator, for routine or bailout use, further studies focused on bivalirudin monotherapy (without GPI) versus heparin plus GPI (discussed below).

3.2. Is Bivalirudin Alone Superior to Heparin Plus Routine GPI?

This was initially studied in the REPLACE-2 (Randomized Evaluation of PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events-2) trial, which demonstrated that bivalirudin with provisional/bail-out GPI (used in 7.2% of patients in the bivalirudin group) is statistically non-inferior to heparin plus planned GPI in preventing acute ischemic events but is associated with a 41% relative reduction in major in-hospital bleeding (2.4% vs 4.1%; p < 0.001) [16]. In contrast to the REPLACE-2 trial which included patients with stable coronary artery disease or low risk ACS, the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy) trial randomized 13,819 moderate to high-risk ACS patients undergoing angiography to heparin ± upstream GPI, bivalirudin ± upstream GPI or bivalirudin monotherapy (with provisional GPI in 9%) [5]. Bivalirudin monotherapy was associated with a significantly lowered risk of major bleeding (3% vs 5.7%; relative risk 0.53; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.43-0.65; p < 0.001) compared to heparin plus GPI.

Following this, the PROTECT TIMI-30 (Protection Against Post-PCI Microvascular Dysfunction and Post-PCI Ischemia Among Anti-Platelet and Anti-Thrombotic Agents) trial in Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI) patients showed that bivalirudin was associated with significantly greater coronary flow reserve but decreased Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) myocardial perfusion grade and longer duration of post-PCI ischemia when compared to heparin (UFH/enoxaparin) plus eptifibatide [17]. Interestingly, while TIMI minor bleeding was lower (0.4% vs. 2.5%, p = 0.027) in the bivalirudin group, there was no difference in TIMI major bleeding. The NAPLES (Novel Approaches for Preventing or Limiting EventS) trial evaluated the efficacy of bivalirudin compared with heparin plus the GPI, tirofiban, in diabetic patients. The study showed similar superior efficacy of bivalirudin in lowering in-hospital bleeding (8.4% vs 20.8%; OR 0.34; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.67; p = 0.002) which was driven by a reduction in minor but not major bleeding. There was no difference in the composite end-point of 3-day death, urgent revascularization and Q-wave MI [18]. Finally, in the ISAR-REACT 4 (Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment 4) trial, bivalirudin was associated with a 56% reduction in major bleeding compared with a combination of heparin and abciximab in patients with NSTEMI undergoing PCI, with similar composite outcomes of ischemic events [19].

HORIZONS-AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) [6] was the first trial which compared bivalirudin with heparin plus GPI in patients with ST-elevation MI (STEMI). Results of this trial revealed significantly reduced rates of Net Adverse Clinical Events (NACE)- a composite of death, re-infarction, stroke, ischemic TVR (9.2% vs. 12.1%; RR 0.76; 95% CI 0.63 to 0.92; p = 0.005), and major bleeding (4.9% vs. 8.3%; RR 0.60; 95% CI 0.46 to 0.77; p < 0.001). Importantly, the risk of all-cause death and cardiac death at 30-days was also lower in the bivalirudin group (RR 0.66, p=0.047 and RR 0.62, p = 0.03 respectively). The risk of acute (within 24 hours of PCI) stent thrombosis was higher with bivalirudin (1.3% vs 0.3%, p < 0.001), with no difference apparent in the rate of overall stent thrombosis at 30 days. Three-year follow up of patients in this trial showed a 43% reduction in cardiac mortality with bivalirudin even after adjusting for the difference in major bleeding [20]. The EUROMAX (European Ambulance Acute Syndrome Angiography) trial [21] compared pre-PCI (upstream) bivalirudin monotherapy (with GPI bailout in 8%) versus heparin with either pre-PCI (upstream) GPI in 58% or bailout GPI in 25%, in the era of newer antiplatelet agents and radial artery access (47%). The results were consistent with HORIZONS-AMI trial with a reduction in the composite of death and major bleeding (5.1% bivalirudin vs 7.6% heparin plus routine GPI; hazard ratio (HR) 0.67; 95% CI 0.46 to 0.97; p = 0.034) and 9.8% with heparin plus bailout GPI (HR 0.52 and 95% CI 0.35-0.75, p = 0.006). The benefits were independent of the type of P2Y12 therapy, arterial access-site or GPI use. As with HORIZONS-AMI, a higher rate of stent thrombosis was noted in the bivalirudin arm.

In summary, the above trials demonstrate a significant reduction in major bleeding and similar composite ischemic and bleeding outcomes with bivalirudin albeit at the cost of a higher risk of acute stent thrombosis. Based on this data, bivalirudin is currently recommended as the preferred anticoagulant for PCI in patients with a high risk of bleeding (class IIa) [22]. Adequate loading with a P2Y12 inhibitor is the key to lower the risk of stent thrombosis with bivalirudin monotherapy.

3.3. Is Bivalirudin Monotherapy Superior to Heparin Monotherapy?

The ISAR-REACT 3 (Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment 3) trial assessed the outcomes of pretreatment of clopidogrel on the effectiveness of bivalirudin and heparin in patients with stable and unstable angina undergoing PCI. The trial showed a favorable outcome in terms of reduced incidence of major bleeding with bivalirudin (3.1% vs 4.6%; 95% CI 0.49 to 0.90; p = 0.008) [23]. However, the high dose of heparin (140U/kg) used in this trial may explain the higher incidence of bleeding in the heparin group. Following this trial, the ARMYDA-7 BIVALVE (Anti-Thrombotic Strategy for Reduction of Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty-Bivalirudin vs Heparin Study) trial [24] was conducted in high bleeding risk patients (one or more of age >75 years, diabetes, or chronic renal failure) using half the dose of heparin (75 U/kg) compared to the dose used in the ISAR-REACT 3 trial. The study again showed a significantly lower risk of bleeding in the bivalirudin arm (1.5% vs 9.9%; OR 0.14; 95% CI 0.03 to 0.51; p = 0.0001) driven by the reduction in access-site hematomas. However, this study was not blinded and was not adequately powered to study the impact of bleeding on mortality. The HEAT-PPCI (How Effective are Antithrombotic Therapies in Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) open-label single-center trial with 1812 patients was the first trial exhibiting the superiority of heparin monotherapy over bivalirudin monotherapy in patients undergoing primary PCI for STEMI. It demonstrated the favorable effect of heparin in lowering the incidence of MACE driven by the significant reduction in re-infarction due to stent thrombosis. There was no difference in major bleeding, and the use of heparin over bivalirudin substantially lowering the drug cost in the setting of primary PCI [25]. Similarly, the NAPLES III (Novel Approaches in Preventing or Limiting Event III) (11) trial exclusively assessed in-hospital bleeding as the primary endpoint, with no difference in major bleeding between bivalirudin and heparin (3.3% vs 2.6%; OR 0.78; 95% CI 0.35 to 1.72; p = 0.54). The lower heparin dose (70-75 U/kg) and absence of GPI use may explain the lack of difference in major bleeding between heparin and bivalirudin monotherapy in these studies. The MATRIX (Minimizing Adverse Hemorrhagic Events by TRansradial Access Site and Systemic Implementation of angioX) trial was a large multicenter study that compared transradial vs transfemoral access in ACS patients [26]. It also assessed the effectiveness of post-PCI bivalirudin infusion over no post-PCI infusion in preventing ischemic complications such as stent thrombosis. There was no significant difference in MACE rates between both the groups. However, patients in the bivalirudin group showed lower rate of bleeding complications (1.4% vs 2.5%; 95% CI 0.39 to 0.78; p = 0.001) and all-cause mortality (1.7% vs 2.3%; CI 0.51 to 0.99; p = 0.042) but also demonstrated higher rates of stent thrombosis (1% vs 0.6%; p = 0.048).

Very recently, VALIDATE-SWEDEHEART (Bivalirudin versus Heparin in ST-Segment and Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Patients on Modern Antiplatelet Therapy in the Swedish Web System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated according to Recommended Therapies Registry Trial), a registry-based, multicenter, RCT compared bivalirudin and heparin alone with no difference in all-cause mortality, MI or major bleeding between the two groups [27]. The patients in this study predominantly received PCI via radial access. Thus, the evidence suggests similar outcomes between heparin and bivalirudin monotherapy, especially in the era of predominant radial arterial access for PCI. However, adequately powered multi-center randomized trials are needed.

3.4. Does Bivalirudin have Better Outcomes Compared with Heparin with Femoral Arterial Access Site?

Radial access lowers access site bleeding by more than 70% compared to femoral access in STEMI patients [28]. The results of the ACUITY trial indicated lower access-site bleeding with bivalirudin monotherapy regimen compared to bivalirudin plus GPI and heparin plus GPI (1% vs 4% vs 3%; p < 0.0001). Similar trends were observed in the NAPLES trial in which UFH plus tirofiban was associated with the highest bleeding risk (75%) at the femoral access site and in the ISAR-REACT 4 trial in which UFH plus abciximab resulted in a 50% increase in femoral access site bleeding compared with bivalirudin. Therefore, it seems clear that the use of GPI predictably results in high rates of access-site bleeding when femoral arterial access is used for PCI. The interaction between antithrombotic agent and arterial access site on major bleeding has yielded conflicting results. In a sub-study of the ACUITY trial, the reduction in 30-day major bleeding in the bivalirudin group compared with the heparin plus GPI group was noted only in patients undergoing PCI via femoral access, and not in patients undergoing radial access. Non-access-site or organ bleeding was reduced by bivalirudin in both radial and femoral groups [29]. The EUROMAX trial evaluated bivalirudin, heparin plus routine GPI and heparin plus bailout GPI in patients undergoing PCI via either femoral or radial access. The results demonstrated a decreased number of bleeding events in the bivalirudin group, irrespective of the access site. This was further evaluated in the MATRIX trial [30], in which 8404 patients with ACS were randomly assigned to receive radial (4197) and femoral (4207) access. Of these, UFH was used in 49.9% and 45.5% patients of radial and femoral group, respectively. On the other side, 40.1% of patients in the radial group and 40.7% of patients in the femoral group received bivalirudin. The trial showed a reduction in NACE driven by a reduction in major bleeding and all-cause mortality in the radial group compared with the femoral group, independent of whether UFH or bivalirudin was used for PCI. A meta-analysis by Mina et al. showed that bivalirudin lowered major bleeding compared with heparin only in patients treated with femoral access [31]. On the other hand, the radial approach was associated with lower bleeding only in patients treated with heparin and not bivalirudin. Similar findings reporting a lack of synergistic interaction between bivalirudin and radial access in lowering major bleeding were noted in another study [32]. A recent data comparing 67,368 patients anticoagulated with heparin or bivalirudin undergoing primary PCI via transradial access included in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) showed no difference in the composite endpoint of death, myocardial infarction or stroke [33].

3.5. What Questions Need to be Answered in the Future?

3.5.1. Bleeding

Anticoagulation is administered in patients undergoing PCI to prevent ischemic events but is associated with increased risk of bleeding [34]. Several RCTs have shown that bivalirudin decreases the risk of major bleeding over heparin during PCI and this lower rate of bleeding in the bivalirudin group is believed to be associated with the improved mortality over heparin [6, 21, 35]. An NCDR data analysis comparing 513,775 patients who underwent PCI for STEMI showed reduced bleeding events with bivalirudin, although no mortality difference was noted when compared to heparin [36]. The current STEMI guidelines recommend 70-100 U/Kg bolus of heparin with a target ACT of 250-300 secs for Hemotec, and 300-350 for Hemochron when GPI is not used. However, the dose of heparin should be lowered to 50-70U/kg with a target ACT level of 200-250 secs when the routine use of GPI is planned [34]. But these recommendations are mostly based on studies in the era that predates the use of upstream dual antiplatelet therapy and routine stent placement which may require larger anticoagulation doses. Further research is warranted for head to head comparisons between bivalirudin monotherapy and heparin monotherapy. Also, more studies on heparin are necessary to establish an optimal dosing regimen that minimizes bleeding complications while protecting patients from ischemic complications.

3.6. Acute Stent Thrombosis

Thrombotic complications are important predictors of MACE in patients undergoing PCI. As mentioned earlier, bivalirudin is associated with a low risk of bleeding but has been associated with a higher rate of acute stent thrombosis. The mechanism for increased risk of acute stent thrombosis is believed to be short half-life and re-activation of thrombin activity immediately after discontinuation of bivalirudin [37]. This is particularly important in STEMI patients as oral P2Y12 inhibitors, especially clopidogrel may take up to 6 hours for effective platelet inhibition secondary to impaired absorption and variability in pharmacokinetics [38, 39]. This leads to a vulnerable time window, especially in the first few hours exposing many patients to high risk of stent thrombosis. Co-administration of heparin, post-PCI bivalirudin infusion or use of rapid-acting P2Y12 inhibitors are the possible future treatments that demand further prospective trials. The MATRIX trial randomly assigned study participants post-PCI bivalirudin infusion versus control [2] and demonstrated that post-PCI use of bivalirudin was not effective in reducing definite stent thrombosis (0.6% in post-PCI bivalirudin arm and 0.6% in no post-PCI bivalirudin arm, p = 0.99). However, the recent analysis from the EUROMAX trial has shown that the risk of acute stent thrombosis can be mitigated by continuing full dose post-PCI bivalirudin [40], without compromising risk of bleeding. Similar outcomes were seen in a recent meta-analysis [7]. Finally, a lower risk of acute stent thrombosis was also noted in the BRIGHT trial with the continuation of full dose bivalirudin (1.75mg/kg) post-PCI for a median duration of 3 hours [41]. Inconsistency between the results of MATRIX and the BRIGHT trial could be based on the lower dose of bivalirudin-infused post-PCI in the MATRIX trial. The VALIDATE-SWEDEHEART study revealed no difference in definite stent thrombosis in between the two groups, however, >90% of the patients in the trial received heparin before randomization. Whether this is derived from post-PCI bivalirudin use or from the effect of the small bolus of heparin administration before randomization is unclear [27], thus questioning the hypothesis of post-PCI bivalirudin infusion. Further RCTs on full dose post-PCI bivalirudin use would be of benefit to predict whether these findings are consistent or due to the selection bias.

SUMMARY

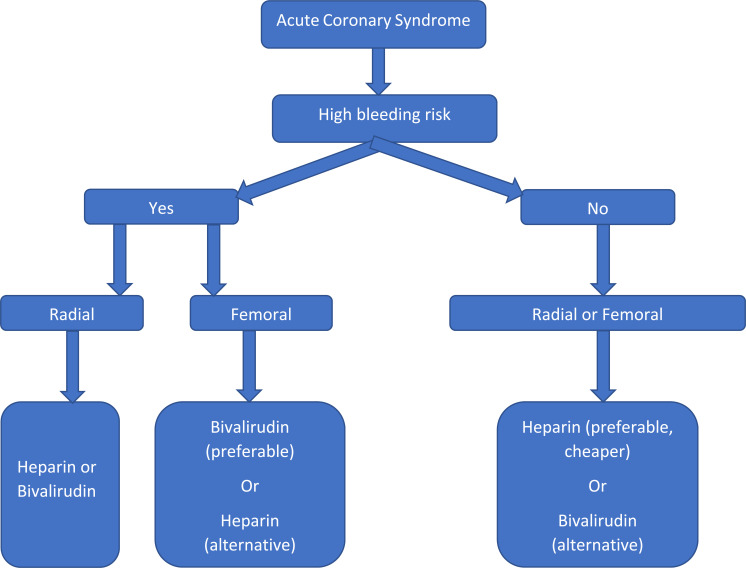

Bivalirudin has emerged as an effective alternative anticoagulation therapy demonstrating its superiority over heparin plus GPI with lower bleeding complications, thus making it as the preferred anticoagulant in patients at high risk of bleeding. In comparison, heparin offers the advantage of a reversible agent, less cost and reduced incidence of ischemic complications. In patients who are at a high risk of bleeding, the radial approach should be adopted whenever possible. If femoral access is unavoidable, then bivalirudin seems to be a safer choice than heparin, and GPI should be avoided in addition to meticulous procedural technique. It is important to emphasize that P2Y12 inhibitor loading should be done prior to bivalirudin use to lower the risk of acute stent thrombosis in the setting of STEMI. Further research is warranted for head to head comparisons between bivalirudin monotherapy and heparin monotherapy in the era of radial access predominance. Also, more studies on heparin are necessary to establish an optimal dosing regimen for minimizing bleeding complications while protecting patients from ischemic complications. We proposed a simplified algorithm in choosing anticoagulant during coronary intervention in ACS as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. (2).

Proposed algorithm for choosing anticoagulant during coronary intervention in acute coronary syndrome.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARD FOR REPORTING

This systematic review was performed in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statements for reporting systematic reviews.

FUNDING

None.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Subherwal S., Peterson E.D., Dai D., Thomas L., Messenger J.C., Xian Y., Brindis R.G., Feldman D.N., Senter S., Klein L.W., Marso S.P., Roe M.T., Rao S.V. Temporal trends in and factors associated with bleeding complications among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A report from the National Cardiovascular Data CathPCI Registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;59(21):1861–1869. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valgimigli M., Frigoli E., Leonardi S., Rothenbühler M., Gagnor A., Calabrò P., Garducci S., Rubartelli P., Briguori C., Andò G., Repetto A., Limbruno U., Garbo R., Sganzerla P., Russo F., Lupi A., Cortese B., Ausiello A., Ierna S., Esposito G., Presbitero P., Santarelli A., Sardella G., Varbella F., Tresoldi S., de Cesare N., Rigattieri S., Zingarelli A., Tosi P., van ’t Hof A., Boccuzzi G., Omerovic E., Sabaté M., Heg D., Jüni P., Vranckx P. Bivalirudin or unfractionated heparin in acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373(11):997–1009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Gara P.T., Kushner F.G., Ascheim D.D., Casey D.E., Jr, Chung M.K., de Lemos J.A., Ettinger S.M., Fang J.C., Fesmire F.M., Franklin B.A., Granger C.B., Krumholz H.M., Linderbaum J.A., Morrow D.A., Newby L.K., Ornato J.P., Ou N., Radford M.J., Tamis-Holland J.E., Tommaso C.L., Tracy C.M., Woo Y.J., Zhao D.X. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61(4):e78–e140. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ndrepepa G., Berger P.B., Mehilli J., Seyfarth M., Neumann F.J., Schömig A., Kastrati A. Periprocedural bleeding and 1-year outcome after percutaneous coronary interventions: Appropriateness of including bleeding as a component of a quadruple end point. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;51(7):690–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone G.W., McLaurin B.T., Cox D.A., Bertrand M.E., Lincoff A.M., Moses J.W., White H.D., Pocock S.J., Ware J.H., Feit F., Colombo A., Aylward P.E., Cequier A.R., Darius H., Desmet W., Ebrahimi R., Hamon M., Rasmussen L.H., Rupprecht H.J., Hoekstra J., Mehran R., Ohman E.M. Bivalirudin for patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355(21):2203–2216. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone G.W., Witzenbichler B., Guagliumi G., Peruga J.Z., Brodie B.R., Dudek D., Kornowski R., Hartmann F., Gersh B.J., Pocock S.J., Dangas G., Wong S.C., Kirtane A.J., Parise H., Mehran R. Bivalirudin during primary PCI in acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358(21):2218–2230. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah R., Rogers K.C., Ahmed A.J., King B.J., Rao S.V. Effect of post-primary percutaneous coronary intervention bivalirudin infusion on acute stent thrombosis: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016;9(13):1313–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P., Clarke M., Devereaux P.J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeymer U., Rao S.V., Montalescot G. Anticoagulation in coronary intervention. Eur. Heart J. 2016;37(45):3376–3385. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lincoff A.M., Bittl J.A., Kleiman N.S., Sarembock I.J., Jackman J.D., Mehta S., Tannenbaum M.A., Niederman A.L., Bachinsky W.B., Tift-Mann J., III, Parker H.G., Kereiakes D.J., Harrington R.A., Feit F., Maierson E.S., Chew D.P., Topol E.J. Comparison of bivalirudin versus heparin during percutaneous coronary intervention (the Randomized Evaluation of PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events [REPLACE]-1 trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 2004;93(9):1092–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briguori C., Visconti G., Focaccio A., Donahue M., Golia B., Selvetella L., Ricciardelli B. Novel approaches for preventing or limiting events (Naples) III trial: randomized comparison of bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin in patients at increased risk of bleeding undergoing transfemoral elective coronary stenting. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015;8(3):414–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Nisio M., Middeldorp S., Büller H.R. Direct thrombin inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353(10):1028–1040. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra044440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao S.V., Ohman E.M. Anticoagulant therapy for percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2010;3(1):80–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.109.884478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bittl J.A., Strony J., Brinker J.A., Ahmed W.H., Meckel C.R., Chaitman B.R., Maraganore J., Deutsch E., Adelman B. Treatment with bivalirudin (Hirulog) as compared with heparin during coronary angioplasty for unstable or postinfarction angina. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333(12):764–769. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509213331204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lincoff A.M., Kleiman N.S., Kottke-Marchant K., Maierson E.S., Maresh K., Wolski K.E., Topol E.J. Bivalirudin with planned or provisional abciximab versus low-dose heparin and abciximab during percutaneous coronary revascularization: Results of the Comparison of Abciximab Complications with Hirulog for Ischemic Events Trial (CACHET). Am. Heart J. 2002;143(5):847–853. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.122173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lincoff A.M., Bittl J.A., Harrington R.A., Feit F., Kleiman N.S., Jackman J.D., Sarembock I.J., Cohen D.J., Spriggs D., Ebrahimi R., Keren G., Carr J., Cohen E.A., Betriu A., Desmet W., Kereiakes D.J., Rutsch W., Wilcox R.G., de Feyter P.J., Vahanian A., Topol E.J. Bivalirudin and provisional glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade compared with heparin and planned glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade during percutaneous coronary intervention: REPLACE-2 randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289(7):853–863. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.7.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson C.M., Morrow D.A., Murphy S.A., Palabrica T.M., Jennings L.K., Stone P.H., Lui H.H., Bulle T., Lakkis N., Kovach R., Cohen D.J., Fish P., McCabe C.H., Braunwald E. A randomized trial to evaluate the relative protection against post-percutaneous coronary intervention microvascular dysfunction, ischemia, and inflammation among antiplatelet and antithrombotic agents: the PROTECT-TIMI-30 trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006;47(12):2364–2373. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tavano D., Visconti G., D’Andrea D., Focaccio A., Golia B., Librera M., Caccavale M., Ricciarelli B., Briguori C. Comparison of bivalirudin monotherapy versus unfractionated heparin plus tirofiban in patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009;104(9):1222–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kastrati A., Neumann F.J., Schulz S., Massberg S., Byrne R.A., Ferenc M., Laugwitz K.L., Pache J., Ott I., Hausleiter J., Seyfarth M., Gick M., Antoniucci D., Schömig A., Berger P.B., Mehilli J. Abciximab and heparin versus bivalirudin for non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365(21):1980–1989. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stone G.W., Clayton T., Deliargyris E.N., Prats J., Mehran R., Pocock S.J. Reduction in cardiac mortality with bivalirudin in patients with and without major bleeding: The HORIZONS-AMI trial (Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeymer U., van ’t Hof A., Adgey J., Nibbe L., Clemmensen P., Cavallini C., ten Berg J., Coste P., Huber K., Deliargyris E.N., Day J., Bernstein D., Goldstein P., Hamm C., Steg P.G. Bivalirudin is superior to heparins alone with bailout GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction transported emergently for primary percutaneous coronary intervention: A pre-specified analysis from the EUROMAX trial. Eur. Heart J. 2014;35(36):2460–2467. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amsterdam E.A., Wenger N.K., Brindis R.G., Casey D.E., Jr, Ganiats T.G., Holmes D.R., Jr, Jaffe A.S., Jneid H., Kelly R.F., Kontos M.C., Levine G.N., Liebson P.R., Mukherjee D., Peterson E.D., Sabatine M.S., Smalling R.W., Zieman S.J. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on practice guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139–e228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kastrati A., Neumann F.J., Mehilli J., Byrne R.A., Iijima R., Büttner H.J., Khattab A.A., Schulz S., Blankenship J.C., Pache J., Minners J., Seyfarth M., Graf I., Skelding K.A., Dirschinger J., Richardt G., Berger P.B., Schömig A. Bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin during percutaneous coronary intervention. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359(7):688–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patti G., Pasceri V., D’Antonio L., D’Ambrosio A., Macrì M., Dicuonzo G., Colonna G., Montinaro A., Di Sciascio G. Comparison of safety and efficacy of bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin in high-risk patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (from the anti-thrombotic strategy for reduction of myocardial damage during angioplasty-bivalirudin vs heparin study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2012;110(4):478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shahzad A., Kemp I., Mars C., Wilson K., Roome C., Cooper R., Andron M., Appleby C., Fisher M., Khand A., Kunadian B., Mills J.D., Morris J.L., Morrison W.L., Munir S., Palmer N.D., Perry R.A., Ramsdale D.R., Velavan P., Stables R.H. Unfractionated heparin versus bivalirudin in primary percutaneous coronary intervention (HEAT-PPCI): An open-label, single centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9957):1849–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60924-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonardi S., Frigoli E., Rothenbühler M., Navarese E., Calabró P., Bellotti P., Briguori C., Ferlini M., Cortese B., Lupi A., Lerna S., Zavallonito-Parenti D., Esposito G., Tresoldi S., Zingarelli A., Rigattieri S., Palmieri C., Liso A., Abate F., Zimarino M., Comeglio M., Gabrielli G., Chieffo A., Brugaletta S., Mauro C., Van Mieghem N.M., Heg D., Jüni P., Windecker S., Valgimigli M. Bivalirudin or unfractionated heparin in patients with acute coronary syndromes managed invasively with and without ST elevation (MATRIX): Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2016;354:i4935. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erlinge D., Omerovic E., Fröbert O., Linder R., Danielewicz M., Hamid M., Swahn E., Henareh L., Wagner H., Hårdhammar P., Sjögren I., Stewart J., Grimfjärd P., Jensen J., Aasa M., Robertsson L., Lindroos P., Haupt J., Wikström H., Ulvenstam A., Bhiladvala P., Lindvall B., Lundin A., Tödt T., Ioanes D., Råmunddal T., Kellerth T., Zagozdzon L., Götberg M., Andersson J., Angerås O., Östlund O., Lagerqvist B., Held C., Wallentin L., Scherstén F., Eriksson P., Koul S., James S. Bivalirudin versus heparin monotherapy in myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377(12):1132–1142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karrowni W., Vyas A., Giacomino B., Schweizer M., Blevins A., Girotra S., Horwitz P.A. Radial versus femoral access for primary percutaneous interventions in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013;6(8):814–823. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamon M., Rasmussen L.H., Manoukian S.V., Cequier A., Lincoff M.A., Rupprecht H.J., Gersh B.J., Mann T., Bertrand M.E., Mehran R., Stone G.W. Choice of arterial access site and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes managed with an early invasive strategy: the ACUITY trial. EuroIntervention. 2009;5(1):115–120. doi: 10.4244/EIJV5I1A18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valgimigli M., Gagnor A., Calabró P., Frigoli E., Leonardi S., Zaro T., Rubartelli P., Briguori C., Andò G., Repetto A., Limbruno U., Cortese B., Sganzerla P., Lupi A., Galli M., Colangelo S., Ierna S., Ausiello A., Presbitero P., Sardella G., Varbella F., Esposito G., Santarelli A., Tresoldi S., Nazzaro M., Zingarelli A., de Cesare N., Rigattieri S., Tosi P., Palmieri C., Brugaletta S., Rao S.V., Heg D., Rothenbühler M., Vranckx P., Jüni P. Radial versus femoral access in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing invasive management: A randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2465–2476. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mina G.S., Gobrial G.F., Modi K., Dominic P. Combined use of bivalirudin and radial access in acute coronary syndromes is not superior to the use of either one separately: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016;9(15):1523–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bagai J., Little B., Banerjee S. Association between arterial access site and anticoagulation strategy on major bleeding and mortality: A historical cohort analysis in the Veteran population. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2018;19(1 Pt B):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jovin I.S., Shah R.M., Patel D.B., Rao S.V., Baklanov D.V., Moussa I., Kennedy K.F., Secemsky E.A., Yeh R.W., Kontos M.C., Vetrovec G.W. Outcomes in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for st-segment elevation myocardial infarction via radial access anticoagulated with bivalirudin versus heparin: A report from the national cardiovascular data registry. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017;10(11):1102–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Gara P.T., Kushner F.G., Ascheim D.D., Casey D.E., Jr, Chung M.K., de Lemos J.A., Ettinger S.M., Fang J.C., Fesmire F.M., Franklin B.A., Granger C.B., Krumholz H.M., Linderbaum J.A., Morrow D.A., Newby L.K., Ornato J.P., Ou N., Radford M.J., Tamis-Holland J.E., Tommaso C.L., Tracy C.M., Woo Y.J., Zhao D.X., Anderson J.L., Jacobs A.K., Halperin J.L., Albert N.M., Brindis R.G., Creager M.A., DeMets D., Guyton R.A., Hochman J.S., Kovacs R.J., Kushner F.G., Ohman E.M., Stevenson W.G., Yancy C.W. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the american college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127(4):e362–e425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742c84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah R., Rogers K.C., Matin K., Askari R., Rao S.V. An updated comprehensive meta-analysis of bivalirudin vs heparin use in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am. Heart J. 2016;171(1):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Secemsky E.A., Kirtane A., Bangalore S., Jovin I.S., Shah R.M., Ferro E.G., Wimmer N.J., Roe M., Dai D., Mauri L., Yeh R.W. Use and effectiveness of bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin for percutaneous coronary intervention among patients with st-segment elevation myocardial infarction in the united states. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016;9(23):2376–2386. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van De Car D.A., Rao S.V., Ohman E.M. Bivalirudin: A review of the pharmacology and clinical application. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2010;8(12):1673–1681. doi: 10.1586/erc.10.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parodi G., Valenti R., Bellandi B., Migliorini A., Marcucci R., Comito V., Carrabba N., Santini A., Gensini G.F., Abbate R., Antoniucci D. Comparison of prasugrel and ticagrelor loading doses in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients: RAPID (Rapid Activity of Platelet Inhibitor Drugs) primary PCI study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61(15):1601–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heestermans A.A., van Werkum J.W., Taubert D., Seesing T.H., von Beckerath N., Hackeng C.M., Schömig E., Verheugt F.W., ten Berg J.M. Impaired bioavailability of clopidogrel in patients with a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Thromb. Res. 2008;122(6):776–781. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clemmensen P., Wiberg S., Van’t Hof A., Deliargyris E.N., Coste P., Ten Berg J., Cavallini C., Hamon M., Dudek D., Zeymer U., Tabone X., Kristensen S.D., Bernstein D., Anthopoulos P., Prats J., Steg P.G. Acute stent thrombosis after primary percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the EUROMAX trial (European Ambulance Acute Coronary Syndrome Angiography). JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015;8(1 Pt B):214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han Y., Guo J., Zheng Y., Zang H., Su X., Wang Y., Chen S., Jiang T., Yang P., Chen J., Jiang D., Jing Q., Liang Z., Liu H., Zhao X., Li J., Li Y., Xu B., Stone G.W. Bivalirudin vs heparin with or without tirofiban during primary percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction: the BRIGHT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(13):1336–1346. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]