Abstract

The following systematic review and meta-analysis compile the current data regarding human controlled COVID-19 treatment trials. An electronic search of the literature compiled studies pertaining to human controlled treatment trials with COVID-19. Medications assessed included lopinavir/ritonavir, arbidol, hydroxychloroquine, tocilizumab, favipiravir, heparin, and dexamethasone. Statistical analyses were performed for common viral clearance endpoints whenever possible. Lopinavir/ritonavir showed no significant effect on viral clearance for COVID-19 cases (OR 0.95 [95% CI 0.50–1.83]). Hydroxychloroquine also showed no significant effect on COVID-19 viral clearance rates (OR 2.16 [95% CI 0.80–5.84]). Arbidol showed no 7-day (OR 1.63 [95% CI 0.76–3.50]) or 14-day viral (OR 5.37 [95% CI 0.35–83.30]) clearance difference compared to lopinavir/ritonavir. Review of literature showed no significant clinical improvement with lopinavir/ritonavir, arbidol, hydroxychloroquine, or remdesivir. Tocilizumab showed mixed results regarding survival. Favipiravir showed quicker symptom improvement compared to lopinavir/ritonavir and arbidol. Heparin and dexamethasone showed improvement with severe COVID-19 cases requiring supplemental oxygenation. Current medications do not show significant effect on COVID-19 viral clearance rates. Tocilizumab showed mixed results regarding survival. Favipiravir shows favorable results compared to other tested medications. Heparin and dexamethasone show benefit especially for severe COVID-19 cases.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV2, Coronavirus, Treatment, Trials, Lopinavir/ritonavir, Arbidol, Hydroxychloroquine, Remdesivir, Tocilizumab, Favipiravir, Heparin, Dexamethasone

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2) is a novel coronavirus responsible for causing coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19). It quickly became a pandemic in the beginning of 2020. Originating in Wuhan, China, the virus rapidly spread to other countries of the world [1]. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared SARS-CoV2 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) [2]. Medications are quickly being tested to assess for a suitable treatment regimen for the novel virus. The following systematic and statistical review assesses the current evidence regarding human controlled COVID-19 treatment trials.

Methods

Data Collection

An electronic search compiled human controlled studies analyzing treatments for COVID-19. Medical therapies investigated included lopinavir/ritonavir, arbidol, hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, favipiravir, heparin, glucocorticoids, interferon, ivermectin, and convalescent plasma. Inclusion criteria included needing a control (whether standard therapy, placebo, or another medication) and testing among human subjects with COVID-19. In vitro and animal studies plus those without controls were not included in the review.

Databases included Google Scholar and Pubmed. Key words included COVID-19, SARS-CoV2, randomized, controlled, human, retrospective, prospective, trial, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, ritonavir, arbidol, umifenovir, tocilizumab, favipiravir, steroids, dexamethasone, glucocorticoids, interferon, ivermectin, remdesivir, azithromycin, heparin, and low-molecular weight heparin. Abstracts and titles were reviewed for relevancy. Studies that had human subjects and a control arm were included in the study; otherwise, they were excluded. Duplicated studies were removed. The studies were organized based on the study medication; some studies presented more than one study medication and were included in more than one group. Statistical analysis was performed if there were two or more studies showing information regarding positive-to-negative conversion rates; number of days varied based on reported similarities among chosen studies.

Statistical Analysis

If there were any common endpoints among the trials collected, a meta-analysis would then be performed. Endpoints were related to viral clearance. Statistical analyses used the Review Manager Version 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) software program. A forest plot was created using the program with the DerSimonian and Laird fixed-effects model to reduce heterogeneity. The mean difference with a confidence interval (CI) of 95% was reported with the inverse variance method. Due to using a scale, the value marking no significance via confidence interval was zero. An I2 greater than 50% suggests significant heterogeneity. If there was significant heterogeneity, a random-effects model would be used instead.

Results

Study Selection

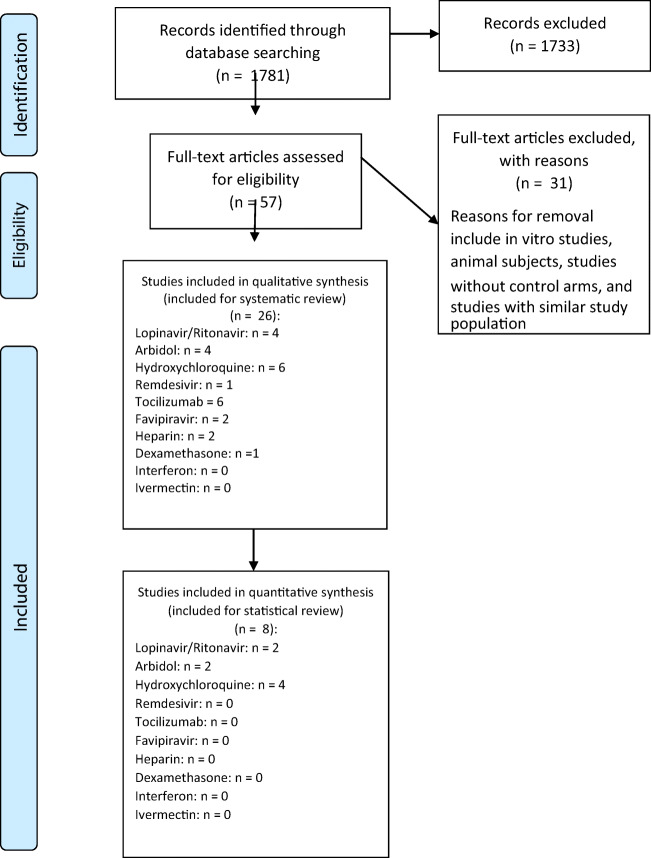

A total of 1781 articles were found with the keywords selected. A total of 57 studies were included initially based on title and abstract review. A total of 26 studies were included in the systematic review: Four studies elaborated about lopinavir/ritonavir; four studies studied arbidol, six for hydroxychloroquine, one for remdesivir, six for tocilizumab, two for favipiravir, two for heparin, and one for dexamethasone. Statistical analyses regarding positive-to-negative conversion rates were possible for lopinavir/ritonavir, arbidol, and hydroxychloroquine. No human controlled trials were found for glucocorticoids, interferons, ivermectin, or convalescent plasma. Statistical analysis regarding positive-to-negative conversion rates was possible for lopinavir/ritonavir (two studies), arbidol (two studies), and hydroxychloroquine (four studies) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart revealing study selection process

Lopinavir/Ritonavir

Treatment

Four controlled trials exist regarding the treatment for COVID-19 (Table 1). Two studies are randomized controlled trials and two are retrospective controlled studies [3–6].

Table 1.

Characteristics of lopinavir/ritonavir studies for COVID-19

| Study | Type | Number of patients | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cao et al. 2020 [3] | Randomized | 199 | No significant difference in 28-day mortality, positive-to-negative RT-PCR conversion, or time to clinical improvement |

| T = 99 | |||

| C = 100 | |||

| Li et al. 2020 [4] | Randomized | 28 | No significant difference in positive-to-negative RT-PCR conversion or time to clinical improvement |

| T = 21 | |||

| C = 7 | |||

| Ye et al. 2020 [5] | Retrospective | 47 (T = 42; C = 5) | Symptoms and labs improved earlier for lopinavir/ritonavir group. Positive-to-negative RT-PCR conversion also decreased with lopinavir/ritonavir. |

| Yan et al. 2020 [6] | Retrospective | 120 | Symptoms improved earlier for lopinavir/ritonavir group. Positive-to-negative RT-PCR conversion also decreased with lopinavir/ritonavir. |

| T = 78 | |||

| C = 42 |

T, treatment group (lopinavir/ritonavir); C, control group

The most recognized is the randomized, controlled, open-label trial by Cao et al. [3] The study showed no significant difference in terms of 28-day mortality or time of positive-to-negative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) conversion. Lopinavir-ritonavir did reduce the time to clinical improvement by 1 day but was considered marginally non-statistically significant. This study had many limitations. The study was organized as an open label and with lack of placebo. About 14% of trial recipients could not complete a full 14-day treatment course due to adverse medication effects including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. However, the incidence of respiratory failure, acute kidney injury, and secondary infection was higher in the standard-care group.

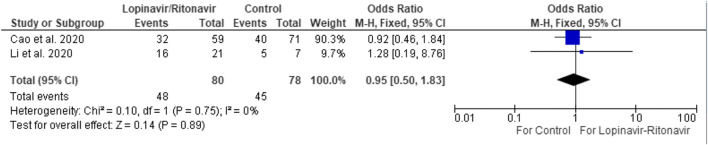

Positive-to-negative RT-PCR conversion was not significant with lopinavir-ritonavir (Fig. 2) [3, 4]. There was no significant difference between the study and control group at 14 days (OR 0.95 [95% CI 0.50–1.83]). Other retrospective studies suggest earlier clearance with lopinavir-ritonavir but did not report the results at 14 days [5, 6]. Furthermore, the two studies that did suggest clearance are retrospective studies while the other two are randomized controlled trials.

Fig. 2.

Positive-to-negative RT-PCR conversion of lopinavir/ritonavir versus control at 14 days

Adverse Effects

The most significant lopinavir/ritonavir side effects include loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea [3, 4]. Diarrhea can possibly become severe [4]. Apart from elevated transaminase levels, other laboratory markers do not significantly differ from the control group [3, 4].

Umifenovir (Arbidol)

Treatment

There are currently four controlled trials discussing the use of arbidol for the treatment of COVID-19 patients (Table 2) [4, 7–9]. Two of the trials are randomized while the other two are retrospective studies. Only Li et al. includes a comparison between arbidol and standard supportive therapy [4]. The two retrospective studies include a comparison with lopinavir/ritonavir [8, 9]. Chen et al. compare arbidol with favipiravir [7].

Table 2.

Characteristics of arbidol studies for COVID-19

| Study | Type | Control medication | Testing medication | Patients | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen C et al. 2020 [7] | Randomized | Favipiravir | Arbidol | 236 | No difference in the 7-day clinical recovery rate between favipiravir and arbidol. Favipiravir decreases the time to fever and cough resolution. |

| T = 116 | |||||

| C = 120 | |||||

| Deng L et al. 2020 [8] | Retrospective | LPV/r | LPV/r + arbidol | 33 | Dual therapy with LPV/r and arbidol showed better 7- and 14-day negative conversion rates and more 7-day chest CT scan improvements compared to LPV/r alone |

| T = 16 | |||||

| C = 17 | |||||

| Zhu Z et al. 2020 [9] | Retrospective | LPV/r | Arbidol | 50 | Arbidol had shorter duration of positive RNA tests compared to LPV/r |

| T = 16 | |||||

| C = 34 | |||||

| Li Y et al. 2020 [4] | Randomized | No anti-viral therapy | Arbidol | 52 | Positive-to-negative conversion rates and CT scan clearance rates were similar between arbidol and the control group at 7 and 14 days. |

| T = 35 | |||||

| C = 17 |

T, testing group; C, control group; LPV/r, lopinavir/ritonavir

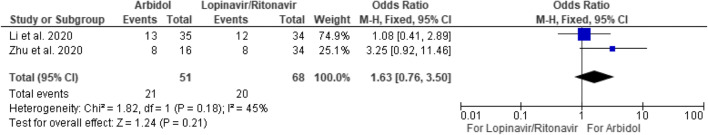

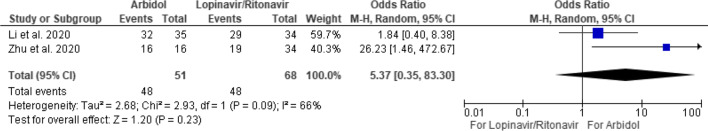

Arbidol was commonly compared with lopinavir/ritonavir [4, 9] while there is no difference in positive-to-negative conversion rates between the two medications at the seventh (OR 1.63 [95% CI 0.76–3.50]) or 14th day (OR 5.37 [95% CI 0.35–83.30]) (Figs. 3 and 4). Of note, for the 14-day comparison, a fixed effect model would show arbidol having more viral clearance compared to lopinavir/ritonavir (OR 5.0 [95% CI 1.50–16.64]). However, there was significant heterogeneity between the two studies (I2 = 66%). A random effects model was therefore employed to counter the heterogeneity, resulting in a nonsignificant difference between the two medications.

Fig. 3.

Positive-to-negative RT-PCR conversion of arbidol versus lopinavir/ritonavir versus at 7 days

Fig. 4.

Positive-to-negative RT-PCR conversion of arbidol versus lopinavir/ritonavir versus at 14 days

Adding arbidol with lopinavir/ritonavir did show significant conversion rates and CT scan improvements compared to lopinavir/ritonavir by itself [8].

While favipiravir did not show any difference compared to arbidol regarding 7-day recovery rate, it did show faster recovery from fever and cough. There was no difference regarding oxygen and non-invasive positive pressure ventilation use between arbidol and favipiravir [7].

Adverse Effects

Arbidol side effects include nausea and diarrhea [4]. Arbidol demonstrated less hyperuricemia compared to favipiravir (p = 0.0014). Both favipiravir and arbidol did not show any significant difference in abnormal liver function tests, psychiatric symptom reaction, or digestive tract reactions [7].

Hydroxychloroquine

Treatment

Six controlled trials exist comparing hydroxychloroquine versus standard therapy (Table 3) [10–15]. Three studies were randomized, one was prospective, and two were retrospective studies.

Table 3.

Characteristics of hydroxychloroquine studies for COVID-19

| Study | Type | Patients | Method of surveillance | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen Z et al. 2020 [10] | Randomized | 62 | CT scan at day 6 | Hydroxychloroquine presented with earlier clinical improvement and positive-to-negative CT scan conversion |

| T = 31 | ||||

| C = 31 | ||||

| Chen J et al. 2020 [11] | Randomized | 30 | RT-PCR at d ay 7 | No significant difference in clinical improvement and positive-to-negative RT-PCR conversion |

| T = 15 | ||||

| C = 15 | ||||

| Gautret et al. 2020 [12] | Prospective | 30 | RT-PCR at day 6 | Hydroxychloroquine presented with earlier positive-to-negative RT-PCR conversion |

| T = 14 | ||||

| C = 16 | ||||

| Tang et al. 2020 [13] | Randomized | 150 | RT-PCR at day 7 | No significant difference in positive-to-negative RT-PCR conversion, symptom improvement, or laboratory value improvements. |

| T = 75 | ||||

| C = 75 | ||||

| Magagnoli et al. 2020 [14] | Retrospective | 368 | No surveillance | Hydroxychloroquine had an increased mortality rate. Ventilator use was similar. |

| T = 210 | ||||

| C = 158 | ||||

| Rosenberg et al. 2020 [15] | Retrospective | 1227 | No surveillance | No difference in in-hospital death, but hydroxychloroquine caused more cardiac complications. |

| T = 1006 | ||||

| C = 221 |

T treatment group (hydroxychloroquine); C control group

The data regarding hydroxychloroquine remains equivocal. The three randomized controlled trials present conflicting information regarding significance in clinical improvement and positive-to-negative conversion [10, 11, 13]. Chen Z et al. observed conversion based on CT scan results, but CT scans have a high negative predictive value for COVID-19 during the pandemic [16–19]. The prospective trial by Gautret et al. showed earlier conversion with hydroxychloroquine [12]. They included patients that took azithromycin with hydroxychloroquine in their study, but that was not included in this analysis. They have yet to present clinical status changes from their study.

A retrospective controlled study among veterans showed increased mortality with hydroxychloroquine use. Mechanical ventilation rates were similar among the two study arms [14]. Another retrospective review showed no difference in in-hospital mortality [15].

The positive-to-negative conversion analysis (Fig. 5) was performed at 6–7 days to include all the studies. RT-PCR or CT scans were used to monitor time to COVID-19 resolution. Hydroxychloroquine did not show significant effects on positive-to-negative conversion time compared to standard therapy (OR 2.16 [95% CI 0.80–5.84]). With significant heterogeneity (I2 = 56%), a random-effects model was used.

Fig. 5.

Positive-to-negative conversion of hydroxychloroquine versus control at 6–7 days

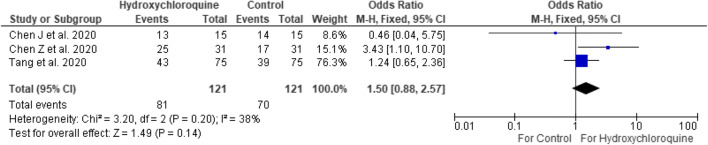

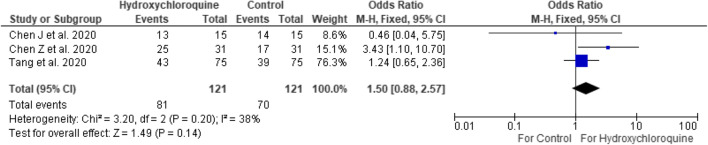

Analyzing the three randomized controlled trials only showed no significant difference between hydroxychloroquine and standard therapy (OR 1.50 [95% CI 0.88–2.57]) (Fig. 6) [10, 11, 13]. This was with nonsignificant heterogeneity (I2 = 38%), and therefore a fixed-effects model was kept.

Fig. 6.

Randomized controlled trials showing positive-to-negative conversion of hydroxychloroquine versus control at 6–7 days

Adverse Effects

Cardiac complications, including cardiac arrest, were more common with hydroxychloroquine use especially when combined with azithromycin [15]. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea and elevated transaminase levels, were mentioned with hydroxychloroquine, but they were not statistically significant compared to the control groups [11, 12, 14].

Remdesivir

Treatment

Currently there is only one published controlled trial with remdesivir (Table 4) [20]. The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed no difference in time to clinical improvement compared to the control arm (hazard ratio 1.23 [95% CI 0.87–1.75]) [20]. A limitation of the study however was that patients in both groups were permitted concomitant use of lopinavir-ritonavir, interferons, and/or corticosteroids.

Table 4.

Characteristics of remdesivir studies for COVID-19

| Study | Type | Patients | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. 2020 [20] | Randomized | 237 | No difference with 28-day mortality, clinical improvement, and viral load change. |

| T = 158 | |||

| C = 79 |

T, treatment group (remdesivir); C, control group

Adverse Effects

About 66% who received remdesivir reported an adverse side effect. The most common side effects were constipation, hypoalbuminemia, hypokalemia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and increased bilirubin [20].

Tocilizumab

Treatment

Six studies assessed the benefits of tocilizumab (Table 5). Tocilizumab presents with mixed results. Half of the studies report no significant benefit compared to standard therapy [21–23], while the other half report improvement for severe cases or improved hospital stay, survival, and freedom from ventilation [24–26]. No studies assessed the duration of positive-to-negative SARS-CoV2 conversion.

Table 5.

Characteristics of tocilizumab studies for COVID-19

| Study | Type | Patients | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colaneri et al. 2020 [21] | Prospective | 42 | Tocilizumab did not reduce 7-day mortality rates. |

| T = 21 | |||

| C = 21 (hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, heparin DVT prophylaxis) | |||

| Martinez-Sanz et al. 2020 [22] | Retrospective | 1229 | Tocilizumab had no difference in death or ICU admissions compared to the control. |

| T = 260 | |||

| C = 969 | |||

| Ip et al. 2020 [23] | Retrospective | 547 | Tocilizumab had no statistically significant benefit in ICU survival. |

| T = 134 | |||

| C = 413 | |||

| Wadud et al. 2020 [24] | Retrospective | 94 | Tocilizumab was associated with increased survival for patients requiring mechanical ventilation |

| T = 44 | |||

| C = 50 | |||

| Capra et al. 2020 [25] | Prospective | 85 | Tocilizumab was associated with improved in-hospital survival |

| T = 62 | |||

| C = 23 (hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/ritonavir) | |||

| Rossi et al. 2020 [26] | Retrospective | 168 | Tocilizumab was associated with improved survival and freedom from ventilation |

| T = 84 | |||

| C = 84 |

T, treatment group (tocilizumab); C, control group

Adverse Reactions

The following studies did not report any associated side effects with tocilizumab compared to standard therapy.

Favipiravir

Treatment

There are two controlled trials regarding the use of favipiravir (Table 4) [7, 27]. The first is a randomized controlled trial comparing favipiravir to arbidol for COVID-19 patients [7]. Arbidol effects are similar to standard therapy [4]. The other is an open-label, non-randomized, prospective trial comparing favipiravir versus lopinavir/ritonavir [27]. Lopinavir/ritonavir is also similar to standard therapy [3, 4] (Table 6).

Table 6.

Characteristics of favipiravir studies for COVID-19

| Study | Type | Control medication | Patients | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. 2020 [7] | Randomized | Arbidol | 236 | Favipiravir has no significant 7-day clinical recovery compared to arbidol. Favipiravir does have decreases the time to fever and cough resolution |

| T = 116 | ||||

| C = 120 | ||||

| Cai et al. 2020 [27] | Prospective | Lopinavir/ritonavir | 80 | Favipiravir showed more 14-day chest CT scan improvement and sooner viral clearance compared to lopinavir/ritonavir |

| T = 35 | ||||

| C = 45 |

T, treatment group (favipiravir); C, control group

Chen et al. showed no significant 7-day recovery rate with favipiravir compared to arbidol. The secondary endpoints of fever and cough relief did resolve significantly sooner with favipiravir compared to arbidol, with fever resolving for all patients at day 4 (versus days 7–8) and cough improving at day 8 (versus day 8+). There was no difference regarding oxygen and non-invasive positive pressure ventilation use [7].

Cai et al. showed faster CT scan improvement and viral clearance with favipiravir compared to lopinavir/ritonavir. At day 14, 32/35 (91.43%) favipiravir subjects had improved chest CT scans compared to 28/45 (62.22%) lopinavir/ritonavir patients (p = 0.004). Viral clearance was sooner at 4 days with favipiravir compared to 11 days with lopinavir/ritonavir (p < 0.001) [27].

Adverse Effects

Favipiravir shows a similar side-effect profile as to lopinavir/ritonavir, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, and elevated transaminase levels [7, 27]. Compared to arbidol, it increases uric acid levels more. While the side effect profile is similar to lopinavir/ritonavir, the frequency of adverse effects is less with favipiravir [27].

Unfractionated and Low-Molecular Weight Heparin

Treatment

Two retrospective controlled studies included data regarding heparin use (Table 5) [28, 29]. These studies involved deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis dosing of unfractionated (15,000 IU/day) and low-molecular weight (40–60 mg/day) heparin (Table 7).

Table 7.

Characteristics of heparin studies for COVID-19

| Study | Type | Patients | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tang et al. 2020 [28] | Retrospective | 449 | No difference in 28-day mortality overall, but among patients with severe sepsis-induced intravascular coagulapathy, heparin improved 28-day mortality |

| T = 99 | |||

| C = 350 | |||

| Shi et al. 2020 [29] | Retrospective | 42 | No difference in positive-to-negative clearance rate or duration of hospital stay |

| T = 21 | |||

| C = 21 |

T treatment group (heparin); C control group

Tang et al. showed no difference in 28-day mortality rates. Most patients received low-molecular weight heparin. They note significant improvement in heparin users among those with severe sepsis-induced intravascular coagulopathy. This was determined by a scoring system utilizing platelet count, prothrombin time, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scoring [28].

Shi et al. showed no difference in outcomes including clinical improvement and positive-to-negative conversion rate. All patients in the study improved [29].

Adverse Effects

The studies included in the review did not report adverse effects. However, all heparin medications have well-documented side-effects including hemorrhage, osteoporosis, renal tubular acidosis type 4 with hyperkalemia, and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia [30–32]. Adverse effects of low-molecular weight heparin are more common in patients with kidney injury [33]. Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis presents with a lower rate of side-effects [34].

Dexamethasone

Treatment

One large randomized controlled trial, the RECOVERY Trial, found an overall benefit when assessing all COVID19 cases together (Table 8) [35]. While there was no benefit for those without oxygen needs, dexamethasone reduced mortality by one-fifth in patients requiring noninvasive oxygen therapy, and by one-third in those requiring mechanical ventilation. Dexamethasone also reduced hospital length of stay and progression to needing invasive mechanical ventilation.

Table 8.

Characteristics of dexamethasone studies for COVID-19

| Study | Type | Patients | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horby et al. 2020 [35] | Randomized | 6425 | Dexamethasone reduced 28-day mortality, especially in those requiring any form of oxygenation. |

| T = 2104 | |||

| C = 4321 |

T, treatment group (dexamethasone); C, control group

Adverse Reactions

While the RECOVERY trial does not report any adverse reactions compared to the standard therapy, glucocorticoids have multiple side-effects. Adverse reactions from acute use include altered mental status, hyperglycemia, increased risk for infection, hypertension, arrhythmias, and myopathy [36, 37].

Discussion

Lopinavir/ritonavir, arbidol, hydroxychloroquine, favipiravir, remdesivir, and heparin are medications that have been tested in human controlled trials for COVID-19 treatment. For the meta-analyses, neither lopinavir/ritonavir nor hydroxychloroquine showed significant positive-to-negative conversion rates. The systematic review revealed inconclusive or negative results for all medications regarding clinical improvement. Favipiravir showed significant improvement compared to its competitor medications, but there were no supportive therapy or placebo-controlled trials. Heparin showed significant clinical improvement only with those with severe COVID-19. Apart from heparin, the adverse effects of the medications mainly include gastrointestinal symptoms.

Lopinavir, a HIV protease inhibitor, inhibits the major protease involved in COVID-19 replication and development of functional viral proteins. Ritonavir acts to increase the levels of lopinavir and improve bioavailability [38–40]. Lopinavir/ritonavir along with ribavirin were previously used to treat SARS in non-randomized clinical trials to prevent development of ARDS [41]. In vitro studies show an antiviral effect of lopinavir on COVID-19 [42]. However, human trials show no significant difference in clinical improvement and viral shedding. Furthermore, a comparison trial shows inferiority to arbidol regarding viral clearance [9].

While arbidol has displayed antiviral effects with previous coronaviruses [43–45], the mechanism of action on COVID-19 is currently unknown. In human trials, arbidol shows no significant positive-negative conversion rate or recovery time compared to standard therapy or lopinavir/ritonavir [4, 9]. The meta-analysis comparing 7- and 14-day viral clearance between arbidol and lopinavir/ritonavir possibly favored arbidol significantly. Employing a random-effects model to account for large heterogeneity removed the statistical significance. It does show promise for post-exposure prophylaxis [45].

Hydroxychloroquine, a member of the 4-aminoquinolines, works by neutralizing the acidic potential of lysosomes resulting in an inhibition of cell chemotaxis, phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and interferon release [46–58]. In vitro studies have shown its anti-viral effects on COVID-19, specifically by preventing viral infusion by altering the pH of cell membranes and impairing ACE2 receptor-mediated entry. It further disrupts viral activity inside the cell [48]. Combining all the hydroxychloroquine human trials showed no benefit with reducing COVID-19 viral shedding time. Most of these studies included azithromycin. One retrospective trial suggests increase mortality with hydroxychloroquine use [14]. The ineffectiveness, high side-effect profile, and increased mortality caused researchers from the Solidarity Trial—a trial comparing the effects of hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, lopinavir-ritonavir, and interferon-beta—to cancel their hydroxychloroquine study arm [49, 50]. There are no human trials showing the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 prophylaxis. Side-effects include visual abnormalities, gastrointestinal issues, cardiac arrhythmias with QT interval prolongation, drug-induced psychosis, and leukopenia. It also interacts with various other medications, including heparin to increase the risk of the bleeding and lopinavir/ritonavir to further prolong the QT interval [51].

Remdesivir is a prodrug that is metabolized into an analogue of adenosine triphosphate, allowing it to inhibit viral RNA polymerases [52]. In vitro studies exhibit its potential in combating SARS-CoV2 [52, 53]. A cohort study suggested potential benefit as compassionate use for severe COVID-19 [53]. However, the randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial included in the review showed no statistical effect with remdesivir regarding clinical improvement, mortality, and viral load change [20]. Adverse effects were not significant among the groups. Limitations to the study included both study groups allowing for other therapies (i.e., glucocorticoids and lopinavir/ritonavir), although their use was not significantly different among the groups. Remdesivir was also started late in some of the study patients. The study was also considered underpowered [20].

Tocilizumab is an IL-6 antibody that suppresses acute phase reactants [54]. It shows a possible benefit for patients with COVID19. Few studies showed survival benefit plus decreased risk of ventilation and disease progression. However, other studies showed no significant benefit. More studies are required to establish the true benefit of tocilizumab.

Favipiravir is a broad spectrum antiviral against RNA viruses. Inside infected host cells, it becomes phosphorylated into favipiravir-RTP and inhibits viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [55, 56]. Favipiravir also suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) production [57, 58]. The human COVID-19 trials with favipiravir are compared with two specific controls. Compared to arbidol, favipiravir reduces symptom duration [7]. Compared to lopinavir/ritonavir, favipiravir reduces viral shedding time and hastens chest CT scan improvement while having fewer side effects [27]. Favipiravir adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms and elevated uric acid levels [7, 27] Its safe profile has made it a preferred medical therapy for those with cardiovascular and renal disease [59, 60].

Heparin has various non-anticoagulant properties including reducing IL-6-associated inflammation [61–63]. IL-6 causes hypercoagulation [63]. Levels are significantly higher in severe COVID-19 patients [61, 64, 65]. Heparin binds to IL-6, reducing the interaction between IL-6, SIL-6R, and sgp130 [66]. This benefit may explain the meta-analysis findings showing ARDS-associated mortality benefit with early low-molecular weight heparin initiation [67]. Heparin also binds to various viral entry proteins, including herpes simplex, zika, and SARS [68–70]. Similarly, it attaches to the S1 spike protein of COVID-19 and causes a conformational change, inhibiting viral membrane fusion with the cell wall [71]. The current studies suggest benefit mainly with severe COVID-19 cases [28, 29].

Dexamethasone shows promise with decreased mortality in overall COVID-19 cases. The benefit is particularly seen with patients requiring supplemental oxygenation or mechanical ventilation. There was no benefit for mild cases. This may be due to dexamethasone suppressing the cytokine storm [72]. While only one study showed results regarding dexamethasone, it was a large, randomized controlled trial.

Limitations

The meta-analysis portion of the study has some limitations. The first limitation is the small number of patients in the trials and therefore the overall analysis. Another limitation is the use of surrogate endpoints to complete the meta-analysis. This is regarding the use of CT scan resolution for viral clearance in the hydroxychloroquine analysis. Chest CT scans have significant negative predictive value, but is not directly comparable to RT-PCR [16–19]. The endpoints were not well-established among all reviewed medications, making it difficult to compare them between studies.

Regarding the systematic review, publication bias influences the information presented. Favipiravir trials on COVID-19 only involve those compared with other medications and not with a placebo or supportive therapy control arm. The heparin and dexamethasone studies mainly involved the level of severity of COVID-19 rather than having the infection itself.

Conclusion

Current investigated medications do not hasten viral clearance time. Clinical improvement is equivocal with lopinavir/ritonavir, arbidol, hydroxychloroquine, and remdesivir. Favipiravir shows faster viral clearance and clinical improvement compared to lopinavir/ritonavir and arbidol. Heparin shows benefit in patients with severe COVID-19 infections.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

No patients or test subjects were required in the formation of this meta-analysis.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Covid-19

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 36. 2020.

- 3.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, Liu W, Wang J, Fan G, Ruan L, Song B, Cai Y, Wei M, Li X, Xia J, Chen N, Xiang J, Yu T, Bai T, Xie X, Zhang L, Li C, Yuan Y, Chen H, Li H, Huang H, Tu S, Gong F, Liu Y, Wei Y, Dong C, Zhou F, Gu X, Xu J, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Li H, Shang L, Wang K, Li K, Zhou X, Dong X, Qu Z, Lu S, Hu X, Ruan S, Luo S, Wu J, Peng L, Cheng F, Pan L, Zou J, Jia C, Wang J, Liu X, Wang S, Wu X, Ge Q, He J, Zhan H, Qiu F, Guo L, Huang C, Jaki T, Hayden FG, Horby PW, Zhang D, Wang C. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Xie Z, Lin W, Cai W, Wen C, Guan Y, et al. An exploratory randomized, controlled study on the efficacy and safety of lopinavir/ritonavir or arbidol treating adult patients hospitalized with mild/moderate COVID-19 (ELACOI). MedRxiv. 2020.

- 5.Ye XT, Luo YL, Xia QF, Sun QF, Ding JG, Zhou Y, et al. Clinical efficacy of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:3390–3396. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan D, Liu XY, Zhu Y, Huang L, Dan B, Zhang G, et al. Factors associated with prolonged viral shedding and impact of lopinavir/ritonavir treatment in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. MedRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Chen C, Huang J, Cheng Z, Wu J, Chen S, Zhang Y, et al. Favipiravir versus arbidol for COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. MedRxiv. 2020.

- 8.Deng L, Li C, Zeng Q, Liu X, Zhang H, Hong Z, et al. Arbidol combined with LPV/r versus LPV/r alone against corona virus disease 2019: a retrospective cohort study. J Inf Secur. 2020. 10.1016/j.inf.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Zhu Z, Lu Z, Xu T, Chen C, Yang G, Zha T, Lu J, Xue Y. Arbidol monotherapy is superior to lopinavir/ritonavir in treating COVID-19. J Inf Secur. 2020;81:e21–e23. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z, Hu J, Zhang Z, Jiang S, Han S, Yan D, et al. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: results of a randomized clinical trial. MedRxiv. 2020.

- 11.Chen J, Liu D, Liu L, Liu P, Xu Q, Xia L, et al. A pilot study of hydroxychloroquine in treatment of patients with common 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19). J ZheJiang Uni. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, Hoang VT, Meddeb L, Mailhe M, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020:105949. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 13.Tang W, Cao Z, Han M, Wang Z, Chen J, Sun W, et al. Hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: an open-label, randomized, controlled trial. MedRxiv. 2020.

- 14.Magagnoli J, Narendran S, Pereira F, Cummings T, Hardin JW, Sutton SS, et al. Outcomes of hydroxychloroquine usage in United States veterans hospitalized with Covid-19. MedRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Rosenberg ES, Dufort EM, Udo T, Wilberschied LA, Kumar J, Tesoriero J, Weinberg P, Kirkwood J, Muse A, DeHovitz J, Blog DS, Hutton B, Holtgrave DR, Zucker HA. Association of treatment with hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in the New York state. JAMA. 2020;323:2493. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bai H, Hsieh B, Xiong Z, Halsey K, Choi JW, Tran TML, et al. Performance of radiologists in differentiating COVID-19 from viral pneumonia on chest CT. Radiol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiol. 2020:200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Fang Y, Zhang H, Xie J, Lin M, Ying L, Pang P, et al. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiol. 2020:200432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Wang S, Kang B, Ma J, Zeng X, Xiao M, Guo J. A deep algorithm using CT images to screen for corona virus disease (COVID-19). MedRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, Du R, Zhao J, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colaneri M, Bogliolo L, Valsecchi P, Sacchi P, Zuccaro V, Brandolino F, Montecucco C, Mojoli F, Giusti E, Bruno R, the COVID IRCCS San Matteo Pavia Task Force Tocilizumab for treatment of severe COVID-19 patients: preliminary results from SMAtteo COvid19 Registry (SMACORE) Microorganisms. 2020;8:695. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8050695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Sanz J, Muriel A, Ron R, Herrera S, Perez-Molina JA, Moreno S, et al. Effects of tocilizumab on mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a multicenter cohort study. MedRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Ip A, Berry DA, Hansen E, Goy AH, Pecora AL, Sinclaire BA, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and tocilizumab therapy in COVID-19 patients – an observational study. MedRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Wadud N, Ahmed N, Shergil M, Khan M, Krishna M, Gilani A, et al. Improved survival outcome in SARs-CoV-2 (COVID-19) acute respiratory distress syndrome patients with tocilizumab administration. MedRxiv. 2020.

- 25.Capra R, De Rossi N, Mattioli F, Romanelli G, Scarpazza C, Sormani MP, et al. Impact of low dose tocilizumab on mortality rate in patients with COVID-19 related pneumonia. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi B, Nguyen LS, Zimmermann P, Boucenna F, Dubret L, Baucher L, et al. Effect of tocilizumab in hospitalized patietns with severe pneumonia COVID-19: a cohort study. MedRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Cai Q, Yang M, Liu D, Chen J, Shu D, Xia J, et al. Experimental treatment with favipiravir for COVID-19: an open-label control study. Engineering. 2020. 10.1016/j.eng.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Shi C, Wang C, Wang H, Yang C, Cai F, Zeng F, et al. Clinical observations of low molecular weight heparin in relieving inflammation in COVID-19 patients: a retrospective cohort study. MedRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Bengalorkar GM, Sarala N, Venkatrathnamma PN, Kumar TN. Effect of heparin and low-molecular weight heparin on serum potassium and sodium levels. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2011;2:266–269. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.85956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bick RL, Frenkel EP. Clinical aspects of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis and other side effects of heparin therapy. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 1999;5:7–15. doi: 10.1177/10760296990050S103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warkentin TE, Greinacher A. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: recognition, treatment, and prevention: the seventh ACCP conference on antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy. Chest. 2004;126:311–337. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.311S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hull RD, Pineo GF, Valentine KA. Treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1997;24:21–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salzman EW. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 1979;42:171. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson J, Mafham M, Bell J, Linsell L, et al. Effect of dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: preliminary report. MedRxiv. 2020.

- 36.Sholter DE, Armstrong PW. Adverse effects of corticosteroids on the cardiovascular system. Can J Cardiol. 2000;16:505–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacGregor RR, Sheagren JN, Lipsett MB, Wolff SM. Alternate-day prednisone therapy – evaluation of delayed hypersensitivity responses, control of disease and steroid side effects. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:1427–1431. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196906262802601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu X, Wang XJ. Potential inhibitors for 2019-nCoV coronavirus M protease from clinically approved medicines. BioRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Yao TT, Qian JD, Zhu WY, Wang Y, Wang GQ. A systemic review of lopinavir therapy for SARS coronavirus and MERS coronavirus – a possible reference for coronavirus disease-19 treatment option. J Med Virol. 2020;92:556–563. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crosby JC, Heimann MA, Burleson SL, Anzalone BC, Swanson JF, Wallace DW, et al. COVID-19: a review of therapeutics under investigation. JACEP. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Chu CM, Cheng VC, Hung IF, Wong MML, Chan KH, Chan KS, et al. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax. 2004;59:252–256. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choy KT, Wong AYL, Kaewpreedee P, Sia SF, Chen D, Hui KPY, Chu DKW, Chan MCW, Cheung PPH, Huang X, Peiris M, Yen HL. Remdesivir, lopinavir, emetine, and homoharringtonine inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro. Antivir Res. 2020;178:104786. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brooks MJ, Burtseva EI, Ellery PJ, Marsh GA, Lew AM, Slepushkin AN, Crowe SM, Tannock GA. Antiviral activity of arbidol, a broad-spectrum drug for use against respiratory viruses, varies according to test conditions. J Med Virol. 2012;84:170–181. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khamitov RA, Loginova S, Shchukina VN, Borisevich SV, Maksimov VA, Shuster AM. Antiviral activity of arbidol and its derivatives against the pathogen of severe acute respiratory syndrome in the cell cultures. Vopr Virusol. 2008;53:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang J, Wang W, Peng B, Peng W, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. Potential of arbidol for post-exposure prophylaxis of COVID-19 transmission—preliminary report of a retrospective case-control study. ChinaXiv. 2020.

- 46.Kapoor KM, Kapoor A. Role of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 infection – a systematic literature review. MedRxiv. 2020.

- 47.Hurst NP, French JK, Gorjatschko L, Betts WH. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine inhibit multiple sites in metabolic pathways leading to neutrophil superoxide release. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao X, Ye F, Zhang M, Cui C, Huang B, Niu P, et al. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Kupferschmidt K, Cohen J. Race to find COVID-19 treatments accelerates. Science. 2020;367:1412–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.367.6485.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahase E. Covid-19: WHO halts hydroxychloroquine trial to review links with increased mortality risk. BMJ. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Multicenter collaboration group of Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province and Health Commission of Guangdong Province for chloroquine in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia Expert consensus on chloroquine phosphate for the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Zhonghua jie he he hhu xi za zhi (Chinese J Tuberc Respir Dis) 2020;43:185–188. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D, Diaz G, Asperges E, Castagna A, Feldt T, Green G, Green ML, Lescure FX, Nicastri E, Oda R, Yo K, Quiros-Roldan E, Studemeister A, Redinski J, Ahmed S, Bernett J, Chelliah D, Chen D, Chihara S, Cohen SH, Cunningham J, D’Arminio Monforte A, Ismail S, Kato H, Lapadula G, L’Her E, Maeno T, Majumder S, Massari M, Mora-Rillo M, Mutoh Y, Nguyen D, Verweij E, Zoufaly A, Osinusi AO, DeZure A, Zhao Y, Zhong L, Chokkalingam A, Elboudwarej E, Telep L, Timbs L, Henne I, Sellers S, Cao H, Tan SK, Winterbourne L, Desai P, Mera R, Gaggar A, Myers RP, Brainard DM, Childs R, Flanigan T. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2327–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, Yang X, Liu J, Xu M, Shi Z, Hu Z, Zhong W, Xiao G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott LJ. Tocilizumab: a review in rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs. 2017;77:1865–1879. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0829-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Furuta Y, Takahashi K, Kuno-Maekawa M, Sangawa H, Uehara S, Kozaki K, Nomura N, Egawa H, Shiraki K. Mechanism of action of T-705 against influenza virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:981–986. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.981-986.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jin Z, Smith LK, Rajwanshi VK, Kim B, Deval J. The ambiguous base-pairing and high substrate efficiency of T-705 (favipiravir) ribofuranosyl 5′-triphosphate towards influenza A virus polymerase. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanaka T, Kamiyama T, Daikoku T, Takahashi K, Nomura N, Kurokawa M, et al. T-705 (favipiravir) suppresses tumor necrosis factor alpha production in response to influenza virus infection: a beneficial feature of T-705 as an anti-influenza drug. Acta Virol. 2017;61:48–55. doi: 10.4149/av_2017_01_48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Damjanovic D, Divangahi M, Kugathasan K, Small CL, Zganiacz A, Brown EG, Hogaboam CM, Gauldie J, Xing Z. Negative regulation of lung inflammation and immunopathology by TNF-alpha during acute influenza infection. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2963–2976. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chinello P, Petrosillo N, Pittalis S, Biava G, Ippolito G, Nicastri E, on behalf of the INMI Ebola Team QTc interval prolongation duration favipiravir therapy in an ebolavirus-infected patient. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0006034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shiraki K, Daikoku T. Favipiravir, an anti-influenza drug against life-threatening RNA virus infections. Pharmacol Ther 2020, 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Qian Y, Xie H, Tian R, Yu K, Wang R. Efficacy of low molecular weight heparin in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease receiving ventilatory support. J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;11:171–176. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2013.831062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu Y, Mu S, Li X, Liang Y, Wang L, Ma X. Unfractionated heparin alleviates sepsis-induced acute lung injury by protecting tight junctions. J Surg Res. 2019;238:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li X, Ma Y, Chen T, Tang J, Ma X. Unfractionated heparin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of chemokines in human endothelial cells through nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2016;28:117–121. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bester J, Matshailwe C, Pretorius E. Simultaneous presence of hypercoagulation and increased clot lysis time due to IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8. Cytokine. 2018;110:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wan S, Yi Q, Fan S, Lv J, Zhang X, Guo L, et al. Characteristics of lymphocyte subsets and cytokines in peripheral blood of 123 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (NCP). MedRxiv. 2020.

- 66.Mummery RS, Rider CC. Characterization of heparin-binding properties of IL-6. J Immunol. 2000;165:5671–5679. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li J, Li Y, Yang B, Wang H, Li L. Low-molecular-weight heparin treatment for acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2018;11:414–422. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shukla D, Spear PG. Herpesviruses and heparin sulfate: an intimate relationship in aid of viral entry. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:503–510. doi: 10.1172/JCI200113799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ghezzi S, Cooper L, Rubio A, Pagani I, Capobianchi MR, Ippolito G, Pelletier J, Meneghetti MCZ, Lima MA, Skidmore MA, Broccoli V, Yates EA, Vicenzi E. Heparin prevents zika virus induced-cytopathic effects in human neural progenitor cells. Antiviral Re. 2017;140:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vicenzi E, Canducci F, Pinna D, Mancini N, Carletti S, Lazzarin A, Bordignon C, Poli G, Clementi M. Coronaviridae and SARS-associated coronavirus strain HSR1. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:413–418. doi: 10.3201/eid1003.030683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mycroft-West C, Su D, Elli S, Li Y, Guimond S, Miller G, et al. The 2019 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) surface protein (spike) S1 receptor binding domain undergoes conformational change upon heparin binding. BioRxiv. 2020.

- 72.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]