Abstract

The coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemic reported for the first time in Wuhan, China at the end of 2019, which has caused 4648 deaths in China as of July 10, 2020. This study explored the temporal correlation between the case fatality rate (CFR) of COVID-19 and particulate matter (PM) in Wuhan. We conducted a time series analysis to examine the temporal day-by-day associations. We observed a higher CFR of COVID-19 with increasing concentrations of inhalable particulate matter (PM) with an aerodynamic diameter of 10 μm or less (PM10) and fine PM with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 μm or less (PM2.5) in the temporal scale. This association may affect patients with mild to severe disease progression and affect their prognosis.

Keywords: COVID-19, Particulate matter, Case fatality rate, Wuhan

Highlights

-

•

The daily PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations and the daily CFR exhibited great similarity with respect to their temporal variation curves, besides, with an obvious time lag existing between them.

-

•

The association still exists after adjusted for all possible confounders (e.g., temperature and relative humidity, SO2, NO2, CO, and O3).

1. Introduction

COVID-19 is a rising infectious disease that poses a great challenge to global public health. As of 10 July 2020, there were 85,445 confirmed cases in China and 4,648 deaths occurred. Wuhan, the epicenter of the outbreak, have accounted for 58.9% of the total number of cases and 83.2% of the deaths in China. Cui et al. (2003) have found that air pollution can affect the case fatality rate (CFR) of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). The COVID-19 is a respiratory disease with a specific level of likeness to SARS, and there could likewise be a connection between the CFR and air pollution (Porcheddu et al., 2020).

Fattorini et al. (Fattorini and Regoli, 2020) demonstrated that long-term air-quality data had a significant association with the confirmed number of COVID-19 cases in 71 provinces of Italy, suggesting a favorable context for the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 due to air pollution. Coccia et al. (Coccia, 2020) came to a similar conclusion that polluted cities in Italy had a very high number of infected people of COVID-19. Since the association between air pollution and COVID-19 infections has been well described, this study aims to investigate the temporal association between the CFR of COVID-19 and PM concentration (the primary air pollutant in China) in Wuhan.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

We conducted a study to examine the association of PM2.5/PM10 concentrations and the CFR of COVID-19 in Wuhan of China.

2.2. Data and sources

The data of confirmed cases and deaths on COVID-19 were obtained from the National Health Commission of People's Republic of China (http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/xxgzbd/gzbd_index.shtml). We obtained data on daily fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and inhalable particulate matter (PM10) from the National Urban Air Quality Publishing Platform (http://106.37.208.233:20035/). We derived meteorological data, including daily mean temperature and relative humidity, from the China Meteorological Data Sharing Service System.

2.3. Measures of the study

Patients with confirmed COVID-19 were diagnosed based on the guideline (the 4th version) issued by the National Health Commission of China which was released on January 27, 2020 (Zhang et al., 2020).

There is a lag between COVID-19 infection and death. Usually, COVID-19 infection does not immediately cause death but rather goes through several stages (Siddiqi and Mehra, 2020). Therefore, we applied several procedures to estimate the average time from case infection to death. First, with a large sample of COVID-19 cases in China, the median time from diagnosis to death was reported to be 18.9 days (https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-severity-10-02-2020.pdf). Second, we identified the peak time of newly diagnosed cases in Wuhan as around February 5, and peak time of incident COVID-19 deaths in Wuhan as February 23: a lag of 18 days. Adding the 4-day average time from infection to confirmation produced an average period from infection to death of around 22 days (https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-severity-10-02-2020.pdf). Third, as reported by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), most deaths occurred 2–8 weeks after infection (https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf). Thus, we concluded that the average period from infection to death should be around 21 days; this estimate was consistent with the findings of a large cohort study (Verity et al., 2020). Based on this assumption, we calculated the CFR with a 21-day lag. We also examined our results with a lag time varying from 19 to 23 days and found similar findings. The CFR was defined as deaths on day.x/new infection cases on day.x-T, where T was the average time from case infection to death (Cui et al., 2003). We calculated daily CFR of COVID-19 in Wuhan from January 19 to March 15, 2020, as very few cases were diagnosed afterwards.

2.4. Data analysis procedure

We conducted a time series analysis to examine the association of PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations with the CFR of COVID-19 in Wuhan by using multivariate linear regression, with adjustment for temperature, relative humidity, concentrations of sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), carbon monoxide (CO), and ozone (O3). Because of the lockdown of Wuhan and the short study period, we assumed very little changes on either the total number of the population or its age and gender composition. We also examined the lag effects and patterns of PM2.5 and PM10 on the CFR of COVID -19 by analyzing the association between the CFR and single-day daily average PM concentrations on the current day (lag0) and up to 5 days (lag1-lag5) before the date of infection.

3. Results

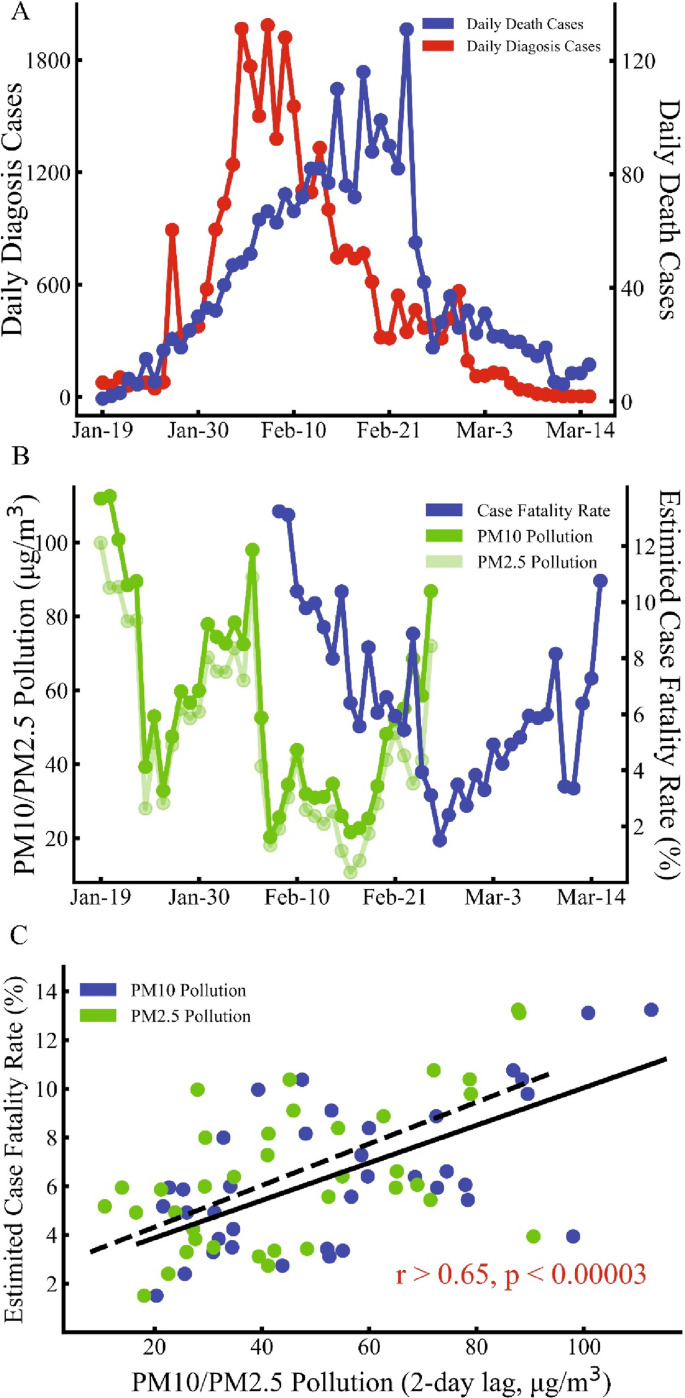

As illustrated in Fig. 1 A, there was a delay of approximately 21 days between the peak of newly diagnosed cases and the peak of daily COVID-19 deaths, which was in line with our prior estimation. From January 19 to March 15, 2020, the daily CFR averaged 6.4% (range, 1.5%–13.2%); the median daily PM2.5 and PM10 were 41.77 μg/m3 and 52.77 μg/m (Fattorini and Regoli, 2020), respectively (range, 10.7–100.0 μg/m3 and 20.3–112.6 μg/m3); the mean daily temperature and relative humidity were 7.18 °C and 81.37%, respectively (range, 1.8°C–18.7 °C and 59.0%–93.0%). As shown in Fig. 1B, we found that the daily concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 changed synchronously and were very similar. We also found that the two air pollutants and the daily CFR exhibited great similarity with respect to their temporal variation curves. Further, an obvious time lag existed between daily CFR and daily PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

The association between PM and CFR. A: The number of daily diagnosed cases and deaths from January 16 to March 16, 2020 in Wuhan. It showed the peak time of newly diagnosed cases in Wuhan was around February 5 and the peak time of new deaths in Wuhan was February 23: a difference of 18 days. B: The case fatality rate (blue dots), PM2.5 (light-green dots), and PM10 (green dots) from February 19 to March 15, 2020. And PM2.5, PM10 and CFR held the same trend with a time lag. C: The daily case fatality rate versus PM2.5 and PM10 pollution. The case fatality rate was positively associated with the 2-day lag PM2.5 (green dots, r = 0.65, P = 2.8 × 10−5) and PM10 (blue dots, r = 0.66, P = 1.9 × 10−5) pollution. Temperature and relative humidity effects were removed during statistical analysis. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

After adjustment for temperature and relative humidity, SO2, NO2, CO, and O3, we found that the CFR was positively associated with all the lag0-lag5 concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 (r > 0.36, P < 0.03). The associations were most significant with lag3 PM2.5 and PM10 (r = 0.65, P = 2.8 × 10−5 and r = 0.66, P = 1.9 × 10−5, respectively). This finding suggested that there was a higher CFR of COVID-19 with increasing concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 in the temporal scale (Fig. 1C). No significant association was found between temperature, relative humidity and the CFR of COVID-19 (r = −0.13, P = 0.44 and r = 0.21, P = 0.22 respectively).

We found that PM2.5, PM10, and CFR significantly decreased from January 19 to March 15, 2020 (r = −0.34, P = 0.038, r = −0.45, P = 0.0055, and r = −0.50, P = 0.015, respectively). After further adjustments for time effects, the CFR of COVID-19 retained a strong positive association with concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 (r = 0.48, P = 0.0043 and r = 0.49, P = 0.0027, respectively). CFR of COVID-19 increased by 0.86% (0.50%–1.22%) and 0.83% (0.49%–1.17%) for each 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 and PM10, respectively. To explore the impact of meteorology on PM, we did a further analysis, and found temperature, relative humidity and rainfall held no significant correlations with PM (r<0.24, p>0.07).

4. Discussion

In this study, we found that the daily concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 changed synchronously, which might be explained by the fact that PM10 contained also fine particles (such as PM2.5). In the further time series analysis to examine the association of PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations with the CFR of COVID-19 in Wuhan, with adjustment for temperature, relative humidity, concentrations of SO2, NO2, CO, and O3, we found COVID-19 deaths were highly correlated with PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations, a trend which was also observed for other respiratory diseases (Zhou et al., 2014). In addition, Bontempi (2020) concluded that PM10 seemed not to affect COVID-19 infections, in accord with our study (r<0.15, p>0.28).

Worldwide, most COVID-19 deaths have occurred in the elderly especially those with underlying health problems, which potentially make them more vulnerable to air pollution. PM2.5, PM10, and CFR significantly decreased from January 19 to March 15, 2020, which might be partially attributed to effectively reduce human activities and improved medical support in Wuhan by Perm et al. (Prem et al., 2020). Patients who died from COVID-19 were likely to be critically ill and most of them had been treated in negative pressure wards (Weiss and Murdoch, 2020). In these wards, air circulation should be limited to avoid potential further COVID-19 transmissions and outdoor PM couldn't affect patients in this stage. Therefore, we speculate that the early exposure to PM may play a very important role, rather than in the period after hospitalization. We theorize that the effect of PM2.5 and PM10 on COVID-19 passing primarily influences patients who progress from gentle to serious infection through increasing system inflammation and oxidative stress, which would decrease cardiopulmonary functions (EPA, ). This process could account for only PM2.5 and PM10 during the first several days of infection showing a significant association with the CFR.

5. Conclusions

We found a positive relationship between PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations and the CFR of COVID-19 in Wuhan, which may provide a further evidence that air pollution provided a favorable context for the spread of the SARS-CoV-2. However, there are some limitations in our study. The first limitation was that the time from infection to death was assumed to be constant for all patients. In fact, the duration of infection to death might be different among patients with COVID-19. Secondly, due to lack of the data of detailed demographic (such as age and sex) and socioeconomic (such as income and schooling) information that wasn't open to the public databases, there might be some underlying explanations for the association between COVID-19 deaths and PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations. However, all potential confounders (e.g., average daily temperature and relative humidity, SO2, NO2, CO, O3) were adjusted to explore a more accurate association between air pollution and COVID-19 deaths by fully exploiting the available data. Thirdly, the data of air pollution was obtained in a limited time span, so the variation of it was slight. But it's still very convincing that the correlation we found between deaths and air pollution in our study. Fourthly, the existing of asymptomatic cases would lead to an underestimated CFR. Longitudinal studies of a larger cohort would be capable of more comprehensive assessment for the association between CFR of COVID-19 and air pollution. Furthermore, due to the lack of specific date of death, the corrected deaths in Wuhan on April 17 were not included in our analysis.

Author contributions

Ye Yao, Jinhua Pan, Zhixi Liu, and Xia Meng contributed equally. Weibing Wang and Haidong Kan contributed equally. Concept and design: Ye Yao, Haidong Kan, and Weibing Wang. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: Ye Yao, Jinhua Pan, Zhixi Liu, Xia Meng, and Weidong Wang. Drafting the manuscript: Ye Yao, Jinhua Pan, and Zhixi Liu. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Haidong Kan and Weibing Wang. Statistical analysis: Ye Yao, Jinhua Pan and Xia Meng.

Funding

This study was sponsored by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [grant number OPP1216424].

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We thank Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

References

- Bontempi E. First data analysis about possible COVID-19 virus airborne diffusion due to air particulate matter (PM): the case of Lombardy (Italy) Environ. Res. 2020;186:109639. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Factors determining the diffusion of COVID-19 and suggested strategy to prevent future accelerated viral infectivity similar to COVID. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138474. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Zhang Z.F., Froines J., Zhao J., Wang H., Yu S.Z., Detels R. Air pollution and case fatality of SARS in the People's Republic of China: an ecologic study. Environ. Health. 2003;2(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA integrated science assessments (ISAs). https://www.epa.gov/isa.

- Fattorini D., Regoli F. Role of the chronic air pollution levels in the Covid-19 outbreak risk in Italy. Environ. Pollut. 2020;264:114732. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcheddu R., Serra C., Kelvin D., Kelvin N., Rubino S. Similarity in case fatality rates (CFR) of COVID-19/SARS-COV-2 in Italy and China. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020;14(2):125–128. doi: 10.3855/jidc.12600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prem K., Liu Y., Russell T.W., Kucharski A.J., Eggo R.M., Davies N., Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases, C.-W. G. Jit M., Klepac P. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e261–e270. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30073-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi H.K., Mehra M.R. COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: a clinical-therapeutic staging proposal. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39(5):405–407. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verity R., Okell L.C., Dorigatti I., Winskill P., Whittaker C., Imai N., Cuomo-Dannenburg G., Thompson H., Walker P., Fu H., Dighe A., Griffin J., Cori A., Baguelin M., Bhatia S., Boonyasiri A., Cucunuba Z.M., Fitzjohn R., Gaythorpe K.A.M., Green W., Hamlet A., Hinsley W., Laydon D., Nedjati-Gilani G., Riley S., van-Elsand S., Volz E., Wang H., Wang Y., Xi X., Donnelly C., Ghani A., Ferguson N. 2020. Estimates of the Severity of COVID-19 Disease. 2020.03.09.20033357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss P., Murdoch D.R. Clinical course and mortality risk of severe COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1014–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30633-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Litvinova M., Wang W., Wang Y., Deng X., Chen X., Li M., Zheng W., Yi L., Chen X., Wu Q., Liang Y., Wang X., Yang J., Sun K., Longini I.M., Jr., Halloran M.E., Wu P., Cowling B.J., Merler S., Viboud C., Vespignani A., Ajelli M., Yu H. Evolving epidemiology and transmission dynamics of coronavirus disease 2019 outside Hubei province, China: a descriptive and modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30230-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Liu Y., Wang L., Kuang X., Xu X., Kan H. Particulate air pollution and mortality in a cohort of Chinese men. Environ. Pollut. 2014;186:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]