Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), which began in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, has caused a large global pandemic and poses a serious threat to public health. More than 4 million cases of COVID‐19, which is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), have been confirmed as of 11 May 2020. SARS‐CoV‐2 is a highly pathogenic and transmissible coronavirus that primarily spreads through respiratory droplets and close contact. A growing body of clinical data suggests that a cytokine storm is associated with COVID‐19 severity and is also a crucial cause of death from COVID‐19. In the absence of antivirals and vaccines for COVID‐19, there is an urgent need to understand the cytokine storm in COVID‐19. Here, we have reviewed the current understanding of the features of SARS‐CoV‐2 and the pathological features, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatments of the cytokine storm induced by COVID‐19. In addition, we suggest that the identification and treatment of the cytokine storm are important components for rescuing patients with severe COVID‐19.

Keywords: COVID‐19, cytokine storm, literature review, SARS‐CoV‐2

Highlights

SARS‐CoV‐2 is a highly pathogenic and transmissible coronavirus that primarily spreads through respiratory droplets and close contact.

A cytokine storm is associated with COVID‐19 severity and is also a crucial cause of death from COVID‐19.

Impaired acquired immune responses and uncontrolled inflammatory innate responses may be associated with the mechanism of the cytokine storm in COVID‐19.

Early control of the cytokine storm through therapies, such as immunomodulators and cytokine antagonists, is essential to improve the survival rate of patients with COVID‐19.

1. INTRODUCTION

An outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) has rapidly spread throughout the world. 1 The initial symptoms of COVID‐19 mainly include fever, cough, myalgia, fatigue, or dyspnea. In the later stages of the disease, dyspnea may occur and gradually develop into acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or multiple organ failure. 2 It has been reported that a cytokine storm is associated with the deterioration of many infectious diseases, including SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) 3 and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). 4 The cytokine storm caused by COVID‐19 has been suggested to be associated with COVID‐19 severity. 2 , 5 However, there is currently a limited understanding of the cytokine storm in severe COVID‐19. Therefore, here, we have discussed the current findings and treatment strategies for the cytokine storm in severe COVID‐19.

2. FEATURES OF SARS‐CoV‐2

SARS‐CoV‐2 is the newest coronavirus known to infect humans. SARS‐CoV, MERS‐CoV, and SARS‐CoV‐2 cause severe pneumonia, while other human coronaviruses, including 229E, OC43, HKU1, and NL63, cause only the common cold. 6 SARS‐CoV‐2 belongs to the genus Betacoronavirus, which also includes SARS‐CoV and MERS‐CoV, both of which have caused SARS and MERS, respectively. 7 SARS‐CoV‐2, SARS‐CoV, and MERS‐CoV have similarities and differences. Genetic sequence analysis has revealed that SARS‐CoV‐2 shares 79% sequence identity with SARS‐CoV and 50% identity with MERS‐CoV. 8 The genomes of SARS‐CoV‐2 and the bat coronavirus RaTG13 are 96.2% homologous. 9 As of 11 May 2020, COVID‐19 has resulted in 278 892 deaths and 4 006 257 cases, with an approximate case fatality rate of 7.0%. 10 SARS‐CoV and MERS‐CoV had a case fatality rate of 9.6% (774/8096) and 34.4% (858/2494), respectively. 11 The reproduction number (R 0) of COVID‐19 is thought to be between 2 and 2.5, 12 which is slightly higher than of SARS (1.7.1.9) and MERS (<1). 13 COVID‐19 appears to be more infectious than SARS and MERS, but maybe less severe. The origins of SARS‐CoV, MERS‐CoV, and SARS‐CoV‐2 are considered to be zoonotic. Both SARS‐CoV and MERS‐CoV originated in bats and spread directly to humans from marked palm civets and dromedary camels, respectively. 14 However, the origin of SARS‐CoV‐2 remains unclear. SARS‐CoV‐2 has been reported to be transmitted between humans through direct contact, aerosol droplets, the fecal‐oral route, and intermediate viruses from symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. 15 SARS‐CoV and MERS‐CoV are also thought to spread from infected to noninfected individuals through direct or indirect contact. 15 The clinical symptoms of SARS, MERS, and COVID‐19 range from mild respiratory diseases to severe acute respiratory diseases. 2 , 16 Patients with mild cases of SARS, MERS, and COVID‐19 primarily exhibit fever, cough, and dyspnea. ARDS is a common severe complication of SARS and MERS. 17 Among 1099 inpatients with COVID‐19, 15.6% of the patients with severe pneumonia were reported to have ARDS. 18 Feng et al 19 proposed that SARS‐CoV‐2 infection triggers an excessive immune response known as a cytokine storm in cases of severe COVID‐19. A cytokine storm is a potentially fatal immune disease characterized by the high‐level activation of immune cells and excessive production of massive inflammatory cytokines and chemical mediators. 20 It is considered to be the main cause of disease severity and death in patients with COVID‐19, 5 and is related to high levels of circulating cytokines, severe lymphopenia, thrombosis, and massive mononuclear cell infiltration in multiple organs. 21

It has been found that SARS‐CoV‐2 genomes from different parts of the world have evolved in different clusters. 22 , 23 Forster et al 23 reported there to be at least three central variants of SARS‐CoV‐2 globally, named A, B, and C. The A type is the most similar to the bat coronavirus and is mainly found in the United States and Australia. The B type is more common in East Asia and has evolved through several mutations. The C type is primarily found in Europe. Different viral isolates exhibit significant differences in pathogenicity and viral load. 24 Notably, given the diverse clinical symptoms of patients, it will be challenging to establish a genotype‐phenotype relationship. With new sequences being uploaded to the global initiative on sharing all influenza data every day, new results may be produced as more data become available. The emergence of variants may add to the challenges of vaccine development.

3. LUNG PATHOLOGY OF COVID‐19

Pathological alterations in patients with COVID‐19 include pulmonary edema, diffuse alveolar injury with the formation of hyaline membranes, the presence of reactive type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, proteinaceous aggregates, fibrinous exudates, monocytes and macrophages within alveolar spaces, and inflammatory infiltration of interstitial mononuclear cells. 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 Electron microscopy has revealed the presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 virus particles in bronchial and alveolar type II epithelial cells, but not in other tissues. 26 , 27 Therefore, although a polymerase chain reaction test may be negative from blood or throat swabs, SARS‐CoV‐2 viral inclusions may be detected in the lungs. Immunohistochemical staining indicated that CD68+ macrophages, CD20+B cells, and CD8+T cells infiltrated the alveolar cavity and alveoli. 26 The levels of CD8+T cells may be slightly higher than that of CD4+T cells within the alveolar septa. 29 These pathological features are very similar to those of SARS‐CoV and MERS‐CoV infections, 30 , 31 indicating that effective treatments for SARS and MERS may be suitable for COVID‐19. Excessive local release of cytokines is considered to be the determinant of pathological alterations and the clinical manifestation of ARDS. 32 Overall, the primary pathological manifestations in the lung tissue are viral cytopathic‐like changes, infiltration of inflammatory cells, and the presence of viral particles. Thus, severe lung injury in patients with COVID‐19 is considered as the result of both direct viral infection and immune overactivation.

4. MECHANISMS OF THE CYTOKINE STORM IN COVID‐19

Cellular entry of SARS‐CoV‐2 depends on the binding of S proteins covering the surface of the virion to the cellular ACE2 receptor 9 , 33 and on S protein priming by TMPRSS2, a host membrane serine protease. 33 After entering respiratory epithelial cells, SARS‐CoV‐2 provokes an immune response with inflammatory cytokine production accompanied by a weak interferon (IFN) response. The proinflammatory immune responses of pathogenic Th1 cells and intermediate CD14+CD16+monocytes are mediated by membrane‐bound immune receptors and downstream signaling pathways. This is followed by the infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils into the lung tissue, which results in a cytokine storm. 34

Particularly, SARS‐CoV‐2 can rapidly activate pathogenic Th1 cells to secrete proinflammatory cytokines, such as granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) and interleukin‐6 (IL‐6). GM‐CSF further activates CD14+CD16+ inflammatory monocytes to produce large quantities of IL‐6, tumor necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α), and other cytokines. 35 Membrane‐bound immune receptors (eg, Fc and Toll‐like receptors) may contribute to an imbalanced inflammatory response, and weak IFN‐γ induction may be an important amplifier of cytokine production. 34 Neutrophil extracellular traps, the extracellular nets released by neutrophils, may contribute to cytokine release. 36 The cytokine storm in COVID‐19 is characterized by a high expression of IL‐6 and TNF‐α. Hirano and Murakami 37 proposed a potential mechanism of the cytokine storm caused by the angiotensin 2 (AngII) pathway. SARS‐CoV‐2 activates nuclear factor‐κB (NF‐κB) via pattern‐recognition receptors. It occupies ACE2 on the cell surface, resulting in a reduction in ACE2 expression, followed by an increase in AngII. In addition to activating NF‐κB, the AngII‐angiotensin receptor type 1 axis can also induce TNF‐α and the soluble form of IL‐6Ra (sIL‐6Ra) via disintegrin and metalloprotease 17 (ADAM17). 38 IL‐6 binds to sIL‐6R through gp130 to form the IL‐6‐sIL‐6R complex, which can activate signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) in nonimmune cells. Both NF‐κB and STAT3 are capable of activating the IL‐6 amplifier to induce various proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including vascular endothelial growth factor, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP‐1), IL‐8, and IL‐6. 39 IL‐6 not only binds to sIL‐6R to act in cis‐signaling but can also bind to the membrane‐bound IL‐6 receptor (mIL‐6R) through gp130 to act in trans‐signaling. The latter can lead to pleiotropic effects on acquired and innate immune cells, resulting in cytokine storms. 40 Collectively, the impaired acquired immune responses and uncontrolled inflammatory innate responses to SARS‐CoV‐2 may cause cytokine storms.

5. ASSOCIATIONS WITH COVID‐19 SEVERITY

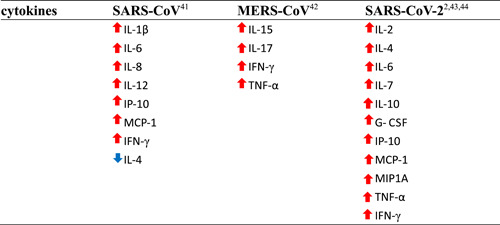

Earlier studies have indicated that the levels of IL‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐8, IL‐12, inducible protein 10 (IP‐10), MCP‐1, and IFN‐γ are increased during SARS‐CoV infection. 41 Low levels of the Th2 cytokine IL‐4 were also observed in patients with SARS. MERS‐CoV infection was also reported to induce increased concentrations of IL‐15, IL‐17, IFN‐γ, and TNF‐α. 42 Some studies have found that patients with severe COVID‐19 exhibit higher levels of IL‐2, IL‐6, IL‐7, IL‐10, IP‐10, MCP‐1, TNF‐α, macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha, and granulocyte‐CSF than patients with mild and moderate infections. 2 , 43 , 44 The fluctuations of these cytokines (eg, IL‐6, IL‐10, and TNF‐α) are small or within the normal range. 43 In addition, increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines (eg, IL‐4 and IFN‐γ) are also observed in patients with COVID‐19. Liu et al 44 found significant and sustained decreases in lymphocyte counts (CD4+cells and CD8+ cells), especially CD8+ T cells, but increases in neutrophil counts in the patients with severe COVID‐19 compared to the mild patients. T cell loss may lead to increased inflammatory responses, while T cell restoration may reduce inflammatory responses during SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Thus, the neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio (NLR) may be predictive of COVID‐19 outcome. Interestingly, Ong et al 45 revealed that the levels of most cytokines, except IL‐1, peaked after respiratory function nadir, indicating that cytokine expression might not be the primary cause of impaired respiratory function in patients with COVID‐19. Dynamic cytokine storms and T cell lymphopenia are associated with COVID‐19 severity. These findings indicate that clinicians should be able to identify patients at risk of developing severe COVID‐19 as early as possible by monitoring dynamic cytokine storms and NLR. Changes in the major cytokines induced by the three coronaviruses discussed here are shown in Table 1, and cytokine secretion patterns based on COVID‐19 severity are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

The major cytokines related to cytokine storms during coronaviruses infection

|

Note: ↑ = increased. ↓ = decreased.

Abbreviations: G‐CSF, granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor; IFN‐γ , interferon γ; IL, interleukin; IP‐10, inducible protein 10; MCP‐1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; MERS‐CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; MIP1A, macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor α.

Table 2.

Patterns of symptoms, cytokine secretion, and T cell lymphopenia related to the severity of COVID‐19 2 , 43 , 44

| State of COVID‐19 | Uninfected individual | Mild and moderate COVID‐19 | Severe COVID‐19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | No symptoms | Fever, myalgia, fatigue, or dyspnea | Fever, myalgia, fatigue, dyspnea, ARDS, or MOF |

| Cytokine patterns | No cytokines | ↑IL‐6, IL‐10, and TNF‐α | ↑↑IL‐6, IL‐10, TNF‐α, IL‐2, and MCP‐1 |

| T cell lymphopenia | No changes | ↓Lymphocytes (CD4+T and CD8+T cells) | ↓↓Lymphocytes (CD4+T cells, especially CD8+T cells) |

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; IL, interleukin; MCP‐1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; MOF, multiple organ failure; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor‐α.

6. THERAPIES FOR THE CYTOKINE STORM IN COVID‐19

Prevention and mitigation of the cytokine storm may be the crux to save patients with severe COVID‐19. Currently, many therapies are being evaluated in clinical trials due to the lack of high‐quality evidence.

6.1. Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids inhibit the host inflammatory response and suppress the immune response and pathogen clearance. 46 In a retrospective study of 401 patients infected with SARS‐CoV, the rational use of corticosteroids shortened hospital stays and reduced the mortality of seriously ill patients without complications. 47 Given the urgent clinical demand, some experts have recommended the rational use of corticosteroids in individuals with severe COVID‐19. 48 , 49 However, the outcomes of corticosteroid use in patients with MERS, SARS, and influenza indicated an impaired clearance of viral RNA and complications (eg, secondary infection, psychosis, diabetes, and avascular necrosis). 50 A recent meta‐analysis of 15 studies found that corticosteroids were associated with significantly higher mortality rates in patients with COVID‐19. 51 Overall, although evidence indicates a potential role for the use of corticosteroids in patients with severe COVID‐19, caution should be exercised given the possibilities of viral rebound and adverse events.

6.2. Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine

Given their in vitro antiviral effects and anti‐inflammatory properties, chloroquine (CQ) and its analog hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) are considered to be potential therapies for COVID‐19. Considering the severe side effects of CQ, HCQ may be a better therapeutic option. CQ and HCQ are able to reduce CD154 expression in T cells 52 and suppress the release of IL‐6 and TNF. 53 A test of the pharmacological activities of CQ and HCQ in SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected Vero cells revealed that low doses of HCQ might mitigate cytokine storm in patients with severe COVID‐19. 54 A small French trial showed significant reductions in viral load and the duration of viral infection for COVID‐19 patients who received 600 mg/day HCQ for 10 days, and these effects could be enhanced by cotreatment with azithromycin. 55 However, a meta‐analysis of clinical trials indicated no clinical benefits of HCQ treatment in patients with COVID‐19. 56 In fact, HCQ might actually do more harm than good given its side effects, which include retinopathy, cardiomyopathy, neuromyopathy, and myopathy. 57 Some clinical trials have suggested that taking high doses of HCQ or CQ may cause arrhythmia. 58,59 The role and risks of HCQ and CQ in the treatment of COVID‐19 still need more data to further verify.

6.3. Tocilizumab

Tocilizumab (TCZ), an IL‐6 receptor (IL‐6R) antagonist, can inhibit cytokine storms by blocking the IL‐6 signal transduction pathway. 60 Currently, a small‐sample clinical trial in China (clinical trial registration ID: ChiCTR2000029765) has found TCZ to be effective in critically ill patients with COVID‐19. 61 Xu et al 62 found that out of 21 patients with severe COVID‐19, 90% recovered after a few days of treatment with TCZ. A retrospective case‐control study of COVID‐19 patients with ARDS revealed that TCZ might improve survival outcomes. 63 However, the risks associated with TCZ (eg, severe infections, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and liver damage) should also be noted. 64 It is unclear whether there are different effects between IL‐6 antagonists (siltuximab) and IL‐6R antagonists (TCZ). Siltuximab binds to sIL‐6 and inhibits only cis‐ and trans‐signaling. TCZ binds to both mIL‐6R and sIL‐6R and inhibits both cis‐ and trans‐signaling and trans‐presentation. 40 , 65 Of note, IL‐6 inhibitors are not able to bind to IL‐6 produced by viruses such as HIV and human herpesvirus‐8. 65 Currently, the application of TCZ for COVID‐19 treatment is under study. The three drugs mentioned above (corticosteroids, HCQ, and TCZ) are immunosuppressants. Owing to the overall damage to the immune system caused by autoimmune diseases and the iatrogenic effects of immunosuppressants, the risk of infection in patients with autoimmune diseases will be increased compared to the general population. Currently, rheumatology societies 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 recommend the use of immunosuppressive drugs (except glucocorticoids) to be suspended in patients with COVID‐19.

6.4. Mesenchymal stem cells

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have a wide range of immune regulatory functions and can inhibit the abnormal activation of T lymphocytes and macrophages and the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. 70 MSC therapy was found to significantly reduce the mortality of patients with H7N9‐induced ARDS and had no harmful side effects. 71 A clinical trial of MSC therapy revealed that MSCs were able to rapidly and significantly improve the clinical symptoms of COVID‐19 without any observed adverse effects. 72 Although the side effects of MSC treatment are rarely reported, the safety and effectiveness of this treatment require further investigation.

6.5. Other therapies

Anakinra, an IL‐1 receptor antagonist that blocks the activity of proinflammatory cytokines IL‐1α and IL‐1β, has been reported to improve the respiratory function and increase the survival rate of patients with COVID‐19. 73 IL‐1 receptor antagonists increase the risk of bacterial infections, but this is extremely rare for anakinra. 65 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors can inhibit inflammatory cytokines and reduce the ability of viruses to infect cells. 74 A small nonrandomized study reported that patients treated with JAK inhibitors exhibited improved clinical symptoms and respiratory parameters. 75 However, JAK inhibitors can also inhibit IFN‐α production, which helps us to fight viruses. 76 Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) can exert various immunomodulatory effects by blocking Fc receptors, which are related to the severity of the inflammatory state. 77 IVIG has been reportedly used to treat patients with COVID‐19. 78 Given its uncertain effectiveness and the risk of severe lung injury and thrombosis, 79 IVIG treatment requires further investigation. Furthermore, convalescent plasma therapy containing coronavirus‐specific antibodies from recovered patients can be directly used to obtain artificial passive immunity. This approach has demonstrated promising results in the treatment of SARS and influenza. 80 , 81 However, a Cochrane systematic review revealed weak evidence on the effectiveness and safety of this therapy for patients with COVID‐19. 82 Some individuals experienced moderate fever or anaphylactic shock after receiving convalescent plasma. Currently, many effective treatments, such as IFNs, TNF blockers, S1P1 receptor agonists, and continuous renal replacement therapy, remain open to further study. A summary of the treatments available for COVID‐19 patients with cytokine storm is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the treatments for COVID‐19 patients with cytokine storm

| Treatments | Mechanisms | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroids | 1. Inhibiting the inflammatory response 46 | 1.Reducing hospital stay 47 | 1. Impaired clearance of viral RNA 50 |

| 2. Suppressing the immune response 46 | 2. Reducing mortality 47 | 2. Adverse events (secondary infection, psychosis, diabetes, and avascular necrosis) 50 | |

| HCQ and CQ | 1. Reducing CD154 expression in T cells 52 | 1. Reducing viral load 55 | 1. Damage to the heart (arrhythmias) 58 , 59 |

| 2. Suppressing the release of IL‐6 and TNF 53 | 2. Reducing the duration of viral infection 55 | 2. Other side effects (retinopathy, cardiomyopathy, neuromyopathy, and myopathy) 57 | |

| TCZ | 1. Blocking the IL‐6 signal transduction pathway 60 | 1. Improving survival outcome 63 | 1. Adverse events (severe infections, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and liver damage) 64 |

| MSCs | 1. Inhibiting the activation of T lymphocytes and macrophages 70 | 1. Reducing mortality 71 | 1. Unclear |

| 2. Inhibiting the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines 70 | 2. Improving clinical symptoms 72 | ||

| IL‐1 receptor antagonist | 1. Blocking the activity of proinflammatory cytokines IL‐1α and IL‐1β 73 | 1. Improving respiratory function 73 | 1. Increasing the risk of bacterial infections 65 |

| 2. Increasing survival rate 73 | |||

| JAK inhibitors | 1. Inhibiting inflammatory cytokines 74 | 1. Improving clinical symptoms 75 | 1. Blocking the production of beneficial cytokine (IFN‐α) 76 |

| 2. Reducing the ability of infected lung cells of the virus 74 | 2. Improving respiratory parameters 75 | ||

| IVIG | 1. Blocking Fc receptors 78 | 1. Exerting various immunomodulatory effects 77 | 1. Severe lung injury 79 |

| 2. Thrombosis 79 | |||

| Convalescent plasma therapy | 1.Transfusion of plasma with antibodies specific 80 , 81 | 1. Obtain artificial passive immunity 80 , 81 | 1. Moderate fever 82 |

| 2. Anaphylactic shock 82 |

Abbreviations: COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; CQ , chloroquine; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; IFN‐α, interferon α; IL‐1, interleukin‐1; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; JAK, Janus kinase; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; TCZ, tocilizumab; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

7. CONCLUSION

The cytokine storm leads to deleterious clinical manifestations or even acute mortality in critically ill patients with COVD‐19. Impaired acquired immune responses and uncontrolled inflammatory innate responses may be associated with the mechanism of the cytokine storm in COVID‐19. Early control of the cytokine storm through therapies, such as immunomodulators and cytokine antagonists, is essential to improve the survival rate of patients with COVID‐19. Although many research articles are published each month, the majority of the existing literature about COVID‐19 comes from descriptive works. In addition, high‐quality evidence will be necessary to understand and treat the cytokine storm of COVID‐19.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the doctors and nurses who have bravely fought the virus during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Hu B, Huang S, Yin L. The cytokine storm and COVID‐19. J Med Virol. 2021;93:250–256. 10.1002/jmv.26232

REFERENCES

- 1. Bogoch II, Watts A, Thomas‐Bachli A, Huber C, Kraemer MUG, Khan K. Potential for global spread of a novel coronavirus from China. J Travel Med. 2020;27(2):taaa011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huang KJ, Su IJ, Theron M, et al. An interferon‐gamma‐related cytokine storm in SARS patients. J Med Virol. 2005;75(2):185‐194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou J, Chu H, Li C, et al. Active replication of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and aberrant induction of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in human macrophages: implications for pathogenesis. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(9):1331‐1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. COVID‐19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033‐1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Corman VM, Muth D, Niemeyer D, Drosten C, et al. Chapter eight—hosts and sources of endemic human coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 2018;100:163‐188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses . The species severe acute respiratory syndrome‐related coronavirus: classifying 2019‐nCoV and naming it SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(4):536‐544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565‐574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou P, Yang X‐L, Wang X‐G, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270‐273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) situation report , 112. 2020.

- 11. Su S, Wong G, Shi W, et al. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24(6):490‐502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization (WHO) . Report of the WHO‐China joint mission on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) . 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 13. Petrosillo N, Viceconte G, Ergonul O, Ippolito G, Petersen E. COVID‐19, SARS and MERS: are they closely related? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:729‐734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses 2019. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:181‐192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Helmy YA, Fawzy M, Elaswad A, Sobieh A, Kenney SP, Shehata AA. The COVID‐19 pandemic: a comprehensive review of taxonomy, genetics, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and control. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zumla A, Chan JF, Azhar EI, Hui DS, Yuen KY. Coronaviruses—drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(5):327‐347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Channappanavar R, Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39(5):529‐539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guan W‐J, Ni Z‐Y, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708‐1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feng Y, Ling Y, Bai T, et al. COVID‐19 with different severity: a multi‐center study of clinical features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1380‐1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Teijaro JR, Walsh KB, Rice S, Rosen H, Oldstone MB. Mapping the innate signaling cascade essential for cytokine storm during influenza virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(10):3799‐3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Merad M, Martin JC. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID‐19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:355‐362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jia Y, Shen G, Zhang Y, et al. Analysis of the mutation dynamics of SARS‐CoV‐2 reveals the spread history and emergence of RBD mutant with lower ACE2 binding affinity. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2020.04.09.034942 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Forster P, Forster L, Renfrew C, Forster M. Phylogenetic network analysis of SARS‐CoV‐2 genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(17):9241‐9243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yao H, Lu X, Chen Q, et al. Patient‐derived mutations impact pathogenicity of SARS‐CoV‐2. medRxiv. 10.1101/2020.04.14.20060160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID‐19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):420‐422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yao XH, He ZC, Li TY, et al. Pathological evidence for residual SARS‐CoV‐2 in pulmonary tissues of a ready‐for‐discharge patient. Cell Res. 2020;30:541‐543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li H, Liu L, Zhang D, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 and viral sepsis: observations and hypotheses. Lancet. 2020;395(10235):1517‐1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang H, Zhou P, Wei Y, et al. Histopathologic changes and SARS‐CoV‐2 immunostaining in the lung of a patient with COVID‐19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):629‐632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Azkur AK, Akdis M, Azkur D, et al. Immune response to SARS‐CoV‐2 and mechanisms of immunopathological changes in COVID‐19. Allergy. 2020;75(7):1564‐1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ding Y, Wang H, Shen H, et al. The clinical pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a report from China. J Pathol. 2003;200(3):282‐289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ng DL, Al Hosani F, Keating MK, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural findings of a fatal case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in the United Arab Emirates, April 2014. Am J Pathol. 2016;186(3):652‐658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parsons PE, Eisner MD, Thompson BT, et al. Lower tidal volume ventilation and plasma cytokine markers of inflammation in patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(1):1‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hoffmann M, Kleine‐Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271‐280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hussman JP. Cellular and molecular pathways of COVID‐19 and potential points of therapeutic intervention. OSF Preprints. 19 May 2020;Web. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Haiming W, Xiaoling X, Yonggang Z, et al. Aberrant pathogenic GM‐CSF+ T cells and inflammatory CD14+CD16+ monocytes in severe pulmonary syndrome patients of a new coronavirus. BioRXiv. 10.1101/2020.02.12.945576 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zuo Y, Yalavarthi S, Shi H, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID‐19. JCI Insight. 2020;5(11):e138999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hirano T, Murakami M. COVID‐19: a new virus, but a familiar receptor and cytokine release syndrome. Immunity. 2020;52(5):731‐733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eguchi S, Kawai T, Scalia R, Rizzo V. Understanding angiotensin II type 1 receptor signaling in vascular pathophysiology. Hypertension. 2018;71(5):804‐810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Murakami M, Kamimura D, Hirano T. Pleiotropy and specificity: insights from the interleukin 6 family of cytokines. Immunity. 2019;50(4):812‐831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moore JB, June CH. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID‐19. Science. 2020;368(6490):473‐474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wong CK, Lam CW, Wu AK, et al. Plasma inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136(1):95‐103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mahallawi WH, Khabour OF, Zhang Q, Makhdoum HM, Suliman BA. MERS‐CoV infection in humans is associated with a pro‐inflammatory Th1 and Th17 cytokine profile. Cytokine. 2018;104:8‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2620‐2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu J, Li S, Liu J, et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS‐CoV‐2 infected patients. EBioMedicine. 2020;55:102763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ong EZ, Chan YFZ, Leong WY, et al. A dynamic immune response shapes COVID‐19 progression. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:879‐882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Favalli EG, Ingegnoli F, De Lucia O, Cincinelli G, Cimaz R, Caporali R. COVID‐19 infection and rheumatoid arthritis: faraway, so close! Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19:102523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen R‐C, Tang X‐P, Tan S‐Y, et al. Treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome with glucosteroids: the Guangzhou experience. Chest. 2006;129(6):1441‐1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shang L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Du R, Cao B. On the use of corticosteroids for 2019‐nCoV pneumonia. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):683‐684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. NIH COVID‐19 Treatment Guidelines. 2020. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 50. Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019‐nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):473‐475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yang Z, Liu J, Zhou Y, Zhao X, Zhao Q, Liu J. The effect of corticosteroid treatment on patients with coronavirus infection: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. The Journal of infection. 2020;81:E13‐E20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wu S‐F, Chang C‐B, Hsu J‐M, et al. Hydroxychloroquine inhibits CD154 expression in CD4 T lymphocytes of systemic lupus erythematosus through NFAT, but not STAT5, signaling. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Savarino A, Boelaert JR, Cassone A, Majori G, Cauda R. Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today's diseases? Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3(11):722‐727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yao X, Ye F, Zhang M, et al. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):732‐739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gautret P, Lagier J‐C, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID‐19: results of an open‐label non‐randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56(1):105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56. Shamshirian A, Hessami A, Heydari K, et al. The Role of Hydroxychloroquine in the Age of COVID‐19: a Periodic Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis. medRxiv. 10.1101/2020.04.14.20065276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Al‐Bari MA. Chloroquine analogues in drug discovery: new directions of uses, mechanisms of actions and toxic manifestations from malaria to multifarious diseases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(6):1608‐1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Borba MGS, de Almeida Val F, Sampaio VS, et al. Chloroquine diphosphate in two different dosages as adjunctive therapy of hospitalized patients with severe respiratory syndrome in the context of coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection: preliminary safety results of a randomized, double‐blinded, phase IIb clinical trial (CloroCovid‐19 study). medRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.04.07.20056424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lane JCE, Weaver J, Kostka K, et al. Safety of hydroxychloroquine, alone and in combination with azithromycin, in light of rapid wide‐spread use for COVID‐19: a multinational, network cohort and self‐controlled case series study. medRxiv. 10.1101/2020.94.08.20054551 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhang C, Wu Z, Li J‐W, Zhao H, Wang GQ. The cytokine release syndrome (CRS) of severe COVID‐19 and interleukin‐6 receptor (IL‐6R) antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce the mortality. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chinese Clinical Trail Registry . A multicenter, randomized controlled trial for the efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in the treatment of new coronavirus pneumonia . 2020. http://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=49409. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 62. Xu X, Han M, Li T, et al. Effective treatment of severe COVID‐19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(20):10970‐10975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wadud N, Ahmed N, Mannu Shergil M, et al. Improved survival outcome in SARs‐CoV‐2 (COVID‐19) acute respiratory distress syndrome patients with tocilizumab administration. medRxiv. 10.1101/2020.05.13.20100081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhang S, Li L, Shen A, Chen Y, Qi Z. Rational use of tocilizumab in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Clin Drug Invest. 2020;40(6):511‐518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Arnaldez FI, O'Day SJ, Drake CG, et al. The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer perspective on regulation of interleukin‐6 signaling in COVID‐19‐related systemic inflammatory response. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. EULAR guidance for patients during COVID‐19 outbreak. 2020. https://www.eular.org/eular_guidance_for_patients_covid19_outbreak.cfm. Accessed April 23, 2020.

- 67. BSR guidance for patients during COVID‐19 outbreak. Rheumatolupdate‐members. 2020. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/clinical-guide-rheumatology-patients-v2-08-april-2020.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- 68. ACR guidance for patients during COVID‐19 outbreak. 2020. https://www.rheumatology.org/announcements. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- 69. Australian Rheumatology Association guidance for patients during COVID‐19 outbreak. 2020. https://arthritisaustralia.com.au/advice-regarding-coronavirus-covid-19-from-the-australian-rheumatology-association/. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- 70. Uccelli A, de Rosbo NK. The immunomodulatory function of mesenchymal stem cells: mode of action and pathways. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2015;1351:114‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chen J, Hu C, Chen L, et al. Clinical study of mesenchymal stem cell treating acute respiratory distress syndrome induced by epidemic Influenza A (H7N9) infection, a hint for COVID‐19 treatment. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb 28] Engineering (Beijing). 10.1016/j.eng.2020.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Leng Z, Zhu R, Hou W, et al. Transplantation of ACE2− mesenchymal stem cells improves the outcome of patients with COVID‐19 pneumonia. Aging Dis. 2020;11(2):216‐228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Cavalli G, De Luca G, Campochiaro C, et al. Interleukin‐1 blockade with high‐dose anakinra in patients with COVID‐19, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hyperinflammation: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Arabi YM, Shalhoub S, Mandourah Y, et al. Ribavirin and interferon therapy for critically Ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome: a multicenter observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(9):1837‐1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cantini F, Niccoli L, Matarrese D, Nicastri E, Stobbione P, Goletti D. Baricitinib therapy in COVID‐19: a pilot study on safety and clinical impact. J Infect. 2020;81(2):318‐356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Richardson P, Griffin I, Tucker C, et al. Baricitinib as potential treatment for 2019‐nCoV acute respiratory disease. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):e30‐e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Liu Q, Zhou Y‐H, Yang Z‐Q. The cytokine storm of severe influenza and development of immunomodulatory therapy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13(1):3‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507‐513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Alijotas‐Reig J, Esteve‐Valverde E, Belizna C, et al. Immunomodulatory therapy for the management of severe COVID‐19. Beyond the anti‐viral therapy: a comprehensive review. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19:102569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mair‐Jenkins J, Saavedra‐Campos M, Baillie JK, et al. The effectiveness of convalescent plasma and hyperimmune immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe acute respiratory infections of viral etiology: a systematic review and exploratory meta‐analysis. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(1):80‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hung IF, To KK, Lee CK, et al. Convalescent plasma treatment reduced mortality in patients with severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(4):447‐456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Valk SJ, Piechotta V, Chai KL, et al. Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin for people with COVID‐19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5(5):D013600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]