Abstract

The number of people suffering from the new coronavirus SARS‐CoV‐2 continues to rise. In SARS‐CoV‐2, superinfection with bacteria or fungi seems to be associated with increased mortality. The role of co‐infections with respiratory viral pathogens has not yet been clarified. Here, we report the course of COVID‐19 in a CLL patient with secondary immunodeficiency and viral co‐infection with parainfluenza.

Keywords: chronic lymphocytic leukemia, COVID‐19, immunodeficiency

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is associated with high mortality rates in cancer patients. 1 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a non‐Hodgkin´s lymphoma, which is associated with severe immunodeficiency. 2 Here, we report the favorable outcome of a CLL patient with COVID‐19 complicated by parainfluenza 4 co‐infection.

2. DISCUSSION

A 52‐year‐old male CLL patient was tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) by RT‐PCR of a nasopharyngeal swab (Day 0). Regarding his CLL, the patient had shown slow disease progression with increasing lymphocytosis and lymphadenopathy after having received first‐line therapy with 12 cycles of venetoclax plus 6 cycles of rituximab until 15 months prior to COVID‐19. First‐line therapy was initiated due to progressive high‐risk CLL (CLL‐IPI 5) to Binet stage B with B symptoms, and the best response to treatment was a MRD‐positive partial response. The patient's CLL disease status 3 months prior to COVID‐19 consisted of a Binet stage A with lymphocytosis of 15.8 × 109/L with otherwise compensated retention parameters, normal bilirubin and liver enzymes, and no increased C‐reactive protein. The patient's cumulative illness rating score was 5 including psoriasis vulgaris with nail and joint involvement, bronchial asthma, and prostatic hyperplasia.

At the time of positive SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR, he presented himself in the emergency room with a productive cough (brownish, mucous secretion) that had been present for 5 days, ageusia and hyposmia. At Day 0, conspicuous laboratory values were a C‐reactive protein of 27.2 mg/L, leukocytes of 28.6 × 109/L, and platelets of 114 × 109/L. Due to his good general condition and only mild symptoms present, the patient was put under home quarantine with regular follow‐up telephone visits scheduled. On Day 7, the patient was admitted to the hospital due to deteriorating general state of health with increasing respiratory distress. Laboratory values at admission were a C‐reactive protein of 25.6 mg/L, procalcitonin of 0.5 µg/L, leukocytes 18.4 × 109/L, and platelets of 115 × 109/L. As COVID‐19 proceeded, we observed a further drop in leukocytes and neutropenia advanced from Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Grade 3 to Grade 4 (Figure 2A). Due to further respiratory deterioration, the patient was admitted to medical intensive care unit (MICU) on Day 12. On Day 16, a respiratory virus panel detected parainfluenza 4 virus besides the already known SARS‐CoV‐2 by RT‐PCR of a nasopharyngeal swab. Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed bilateral ground‐glass opacities, and crazy paving with negligible pleural effusions (Figure 1). Additionally, CLL progression was evident with enlarged mediastinal plus bilateral axillary lymph nodes and splenomegaly.

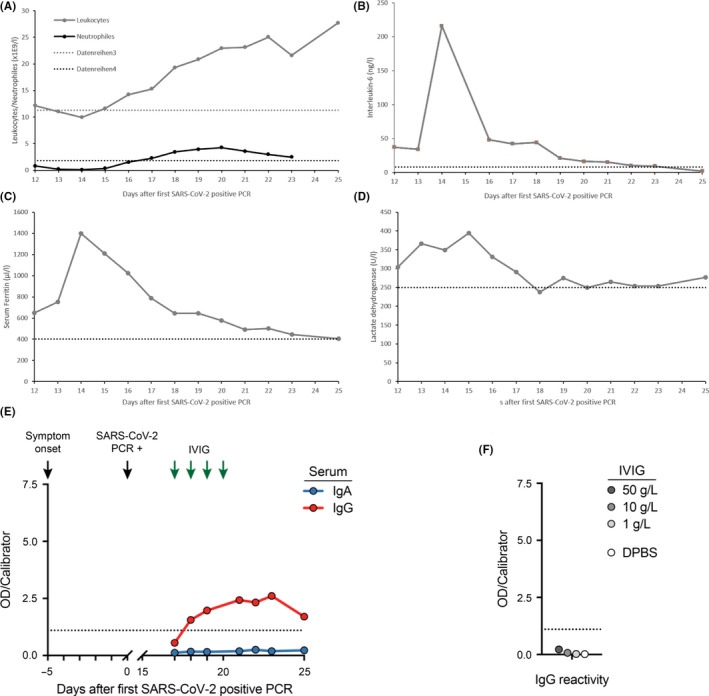

Figure 2.

Changes in laboratory markers and SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein reactivity ELISA. Figures show changes in leukocytes and neutrophils (A), IL‐6 (B), serum ferritin (C), lactate dehydrogenase (D), IgA and IgG reactivity of serum samples (E), and IgG reactivity of the IVIG lot used for treatment of hypogammaglobulinemia and IVIG dilutions in DPBS as determined by ELISA against the S1 domain of the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein S (F). Arrows indicate symptom onset, initial SARS‐CoV‐2‐positive PCR, and IVIG administration (30 g each), respectively. Dashed lines indicate upper reference values (figure A‐D) and assay cutoff for positivity (figure E and F) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

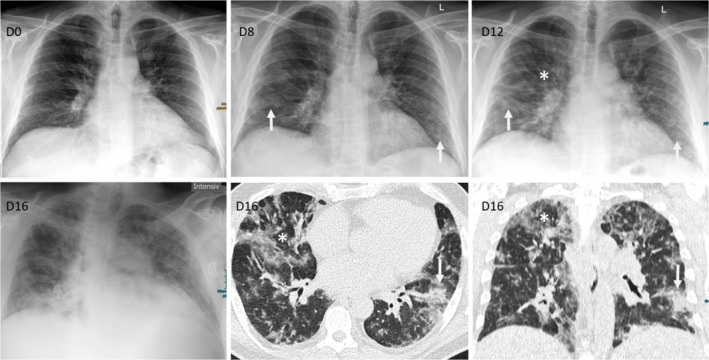

Figure 1.

Radiological Imaging. Chest X‐ray during the course of the disease demonstrated new and increasing infiltrates; D0: normal X‐ray without infiltrations, D8: new COVID‐19 suspicious ground‐glass infiltrations with peripheral and basal distribution (arrow), D12: increasing COVID‐19 suspicious infiltrations with beginning consolidations (arrow), but also additional new unspecific diffuse ground‐glass infiltrations central and apical (asterisk), and D16: X‐ray and low‐dose CT demonstrating a mixed pattern of COVID‐19 suspicious peripheral consolidations with partly crazy paving (arrow) and unspecific viral diffuse ground‐glass infiltrations (asterisk) with peripheral and central distribution (D = day; given are the days after first positive SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

High‐flow oxygen supplementation was applied from Day 16 to Day 20, followed by oxygen administration via nasal cannula. Probatory therapy with oral hydroxychloroquine [200 mg QD] was administered from Day 15 to Day 21. Empiric antibiotic therapy with piperacillin/tazobactam was added from Day 15 to Day 23. Immunoglobulin deficiency [IgG 2.5 g/L, IgM 0.3 g/L, IgA 0.4 g/L] was treated by a course of 30 g immunoglobulin G daily (IVIG) from Day 17 to Day 20.

Serum IgG antibodies targeting the S1 domain of the spike protein of SARS‐CoV‐2 became detectable at low titer by ELISA (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany) on Day 18, while IgA antibodies remained negative (Figure 2E). To exclude cross‐reactivity of the administered immunoglobulins, we tested IVIG of the identical lot by ELISA and did not detect SARS‐CoV‐2 reactivity at concentrations up to 50 g/L (Figure 2F).

With the antibody detection, there was a rapid improvement of the respiratory situation and he could be transferred from MICU to normal care on Day 23. The nasopharyngeal swabs were negative for SARS‐CoV‐2 by RT‐PCR on Day 25 and Day 28. The patient was discharged home on Day 28 without any respiratory residuals. We are planning a BTK‐based outpatient relapse therapy for progressive CLL.

3. CONCLUSION

We report the interdisciplinary treatment of a CLL patient with COVID‐19 complicated by a parainfluenza 4 virus co‐infection. Established risk factors for unfavorable course of COVID‐19 were present with leukocytosis, increased LDH, serum ferritin, and IL‐6 (Figure 1). 3 Progressive CLL with secondary hypogammaglobulinemia increased risk for a severe course that had been additionally promoted by CLL‐related neutropenia. 4 This was further complicated by parainfluenza 4 co‐infection. Patients with leukemia are known for an increased risk for serious parainfluenza virus infections with significant mortality rate. 5 The patient was transferred to MICU, and despite recommendations favoring early intubation, we treated the patient with high‐flow oxygen supplementation via nasal cannula and reassessed the respiratory situation frequently. By this conservative strategy, we were able to avoid emergency intubation and initiation of mechanical ventilation, which is associated with high mortality in cancer patients per se. Our patient met the European Medicines Agency criteria for immunoglobulin substitution. To exclude cross‐reactivity of the administered immunoglobulins, we tested IVIG of the identical lot by ELISA.

In summary, we describe the successful treatment of a CLL patient with severe COVID‐19 with numerous risk factors and secondary complications needing prolonged intensive care. Clinicians should subject respiratory samples to thorough evaluation to detect bacterial, viral, and fungal superinfections. Immunoglobulin substitution should be considered in case of hypogammaglobulinemia according to international recommendations.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed toward patient care, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final manuscript approval.

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The patient was enrolled in the protocol Improving Diagnosis of Severe Infections of Immunocompromised Patients (ISI, Identifier of the University of Cologne Ethics Committee 08‐160) and signed informed consent.

Langerbeins P, Fürstenau M, Gruell H, et al. COVID‐19 complicated by parainfluenza co‐infection in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Eur J Haematol. 2020;105:508–511. 10.1111/ejh.13475

Philipp Koehler and Boris Böll share last authorship.

REFERENCES

- 1. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335‐337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Forconi F, Moss P. Perturbation of the normal immune system in patients with CLL. Blood. 2015;126(5):573‐581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054‐1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ishdorj G, Streu E, Lambert P, et al. IgA levels at diagnosis predict for infections, time to treatment, and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood advances. 2019;3(14):2188‐2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chemaly RF, Hanmod SS, Rathod DB, et al. The characteristics and outcomes of parainfluenza virus infections in 200 patients with leukemia or recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;119(12):2738‐2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]