Abstract

The experiences and challenges of psychotherapists working remotely during the coronavirus pandemic were explored using a mixed‐methods approach. An online survey completed by 335 psychotherapists produced both quantitative and qualitative data with the latter being subject to a reflexive thematic analysis. Large numbers of therapists were using video‐link platforms and the telephone to conduct client sessions. A majority of therapists felt challenged by remote working, with reduced interpersonal cues, feelings of isolation and fatigue, and technical issues frequently cited concerns. At the same time, most therapists considered that remote working had been effective and that clients were comfortable with the process. Two‐thirds of therapists indicated that remote working would now become core business for them. The great majority of therapists thought that remote working skills should be part of formal therapy trainings.

Keywords: coronavirus pandemic, COVID‐19, survey, remote working, mixed methods

1. COVID‐19 AND THERAPY RESEARCH/LITERATURE

At the time of our study, existing literature in the field was scant to non‐existent. The search words ‘COVID‐19 and therapists’ received 16 hit points via our regular EBSCO search, with the majority referring to periodicals and discussion papers. Bao, Sun, Meng, Shi, and Lu (2020) refer to Chinese learnings and findings, for instance with regard to attempts by the Chinese Government to improve public awareness about mental health. Potash, Kalmanowitz, Fung, Anand, and Miller (2020) build on art therapists’ previous experiences from working with Ebola and SARS to ‘help art therapists work effectively with the realities of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID‐19)’.

The impact of the virus is obvious. Bentall (2020) at the University of Sheffield issued a psychological survey of 2,000 people using standardised measures of mental health. Over the period of a single week, Bentall noted 25% of women and 18% of men with anxiety, 23% of women and 21% of men reporting symptoms of depression, and 15% of women and 19% of men evidencing stress. Depression and anxiety peaked in connection with the lockdown announcement. The study showed 38% of those surveyed reporting depression and 36% reporting anxiety symptoms on the day of the announcement, compared with 16% reporting depression and 17% reporting anxiety the previous day.

In response to this impact, we can see attempts within the therapeutic community to provide support. Asmundson and Taylor (2020) issue a call to action for psychosocial researchers and practitioners, stressing the importance of understanding the psychosocial fallout of 2019‐nCoV, such as excessive fear (or lack of concern and due caution) and discrimination, and to find evidence‐based ways of addressing these issues. Reicher, Drury, and Stott (2020) also discuss responses to the virus in the context of different types of ‘psychologies of relevance to the coronavirus pandemic’. Among the periodicals that discuss the impact of COVID‐19, Brown’s (2020) discussion paper stands out. Brown refers to early research (Bentall, 2020) and practical support and discusses the experience with practitioners in detail. Issues such as loss of relational, embodied contact and technical challenges are explored to assess the impact of COVID‐19 on the therapy profession to date.

2. METHODOLOGY

With an epistemological alignment with critical realism (Bhaskar, 1978, 1979), the research explored the experiences and challenges of psychotherapists who have been working remotely during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. A mixed‐methods approach (Bager‐Charleson, McBeath, & du Plock, 2019; Hesse‐Biber, 2010; Landrum & Garza, 2015) was adopted drawing from therapists’ participation in an online survey.

Previous research experience (McBeath, 2019; McBeath, Bager‐Charleson, & Abarbanel, 2019) has confirmed that a well‐designed online survey that is perceived by research participants to have high face validity can deliver a potent blend of both quantitative and qualitative data. Well‐structured survey questions can not only deliver robust and meaningful quantitative data but also offer research participants, through free‐text opportunities, the potential to add a rich and deep vein of qualitative data. In this research project, the qualitative data were analysed through the lens of reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2019).

Historically, views on the appropriateness of quantitative and qualitative research methods have become polarised and captured by the notion of a ‘paradigm war’ (Ukpabi, Enyindah, & Dapper, 2014). In a mixed‐methods approach, there is no inherent conflict with quantitative and qualitative research methods able to make their own distinctive contribution. The power of the mixed‐methods approach has been eloquently articulated by Landrum and Garza (2015):

We argue that together, quantitative and qualitative approaches are stronger and provide more knowledge and insights about a research topic than either approach alone. While both approaches shed unique light on a particular research topic, we suggest that methodologically pluralistic researchers would be able to approach their interests in such a way as to reveal new insights that neither method nor approach could reveal alone. (p. 207)

3. ONTOLOGICAL AND EPISTEMOLOGICAL POSITIONS

The mixed‐methods approach adopted invites reflection on the ontological and epistemological assumptions underpinning the research. Traditionally, quantitative and qualitative methodologies have been seen as distinctly different research approaches and each has been associated with seemingly incompatible and non‐overlapping philosophies (Lund, 2005). From an ontological perspective, quantitative methods have been associated with realism, which holds that there is an objective reality independent of our cognitions and perceptions. In contrast, qualitative approaches have been associated with relativism where reality, as we know it, is seen as an intersubjective and social‐based phenomenon. From an epistemological stance, quantitative approaches have been associated with positivism, which holds that reality is objective and can become known through empirical observation. In contrast, qualitative approaches have been associated with interpretivism. An interpretivist stance assumes that reality is fluid and subjective, and that reality can only be observed as approximations or estimates.

Our approach in this study essentially rejects these dichotomous ontological and epistemological positions and, instead, favours an alignment with the fundamental assumptions underlying critical realism. Originally formulated by Bhaskar (1978, 1979), critical realism is an alternative philosophical position to the classic positivist and interpretivist paradigms and, to some extent, offers a unifying view of reality and the acquisition of knowledge. Critical realism can be viewed as being positioned somewhere between positivism and interpretivism. Critical realism accepts the principle of an objective reality independent of our knowledge. It also accepts that our knowledge of the world is relative to who we are and that, ultimately, our knowledge is embedded in a non‐static social and cultural context.

Critical realism has been regarded as a philosophical position, which would promote both quantitative and qualitative approaches as being important and relevant within research (e.g., McEvoy & Richards, 2003). From a research perspective, a key element of critical realism has been neatly captured by Danermark, Ekström, Jakobsen, and Karlsson (2002) with these words,

there exists both an external world independently of human consciousness, and at the same time a dimension which includes our socially determined knowledge about reality. (pp. 16–17)

4. SURVEY QUESTIONNAIRE

The content of the survey was derived from the authors’ review of contemporary literature on the pandemic, content from professional organisations (e.g., BACP, UKCP), discussions with colleagues and feedback from a pilot survey that involved ten psychotherapists. The survey focused on a number of key issues, which included:

Types of remote working being used by therapists.

Client types—whether they were new, existing or both.

The challenges of remote working.

The perceived effectiveness of remote working.

Therapists’ views of how clients might be feeling about remote working.

The advantages of remote working with clients.

Whether remote working skills should be formally taught in the context of therapy training programmes.

Whether remote working was likely to become core work for therapists after the pandemic has passed.

5. SAMPLING METHOD

A purposive sampling method was employed to identify potential survey respondents, with the social media platforms Facebook and LinkedIn being utilised as the primary social media sources. LinkedIn contains the professional profiles of many hundreds of self‐identified psychotherapists. A second social media source was a number of professional psychotherapy Facebook groups, which included BACP, UKCP, British Psychotherapy Foundation, BPS Psychotherapy Section and other groups, such as ‘Online Therapy Professionals’ and ‘CBT in Private Practice’. A growing number of studies are using social media to identify participant samples in psychotherapy research (e.g., Liddon, Kingerlee, & Barry, 2017; McBeath, 2019; McBeath, Bager‐Charleson, and Abarbanel, 2019). The authors also used their existing academic networks to identify suitable survey participants.

The selection criteria for survey participants required them to be post‐qualified and working clinically as a psychological therapy practitioner. Checks on LinkedIn profiles, contributing members of professional Facebook groups, and the many free‐text comments made by survey respondents provided confidence that the selection criteria were being robustly met.

6. ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The Metanoia Research Ethics Committee gave ethical approval for the research. A link to the data privacy policy of the company that hosted the online survey was provided. The survey introductory page stated that all responses would be treated in confidence.

7. RESULTS: QUANTITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

A total of 335 psychotherapists completed the online survey; this is a sufficiently large number to give confidence that the results can be generalised to the wider practitioner body. Drawing on the latest published number of UKCP clinical registrants (8,331) 1 might serve to illustrate how we can be confident that the survey findings can be generalised. Not all UK psychotherapists are UKCP members; some will be registered with BACP and other bodies. But to get a sense of scale, let's increase the current number of UKCP registrants by approximately 50% to give a round total of 12,000. Working with this figure, our survey response total of 335 allows a margin of error of ±5%. In other words, we could be 95% certain that a percentage figure returned from our sample would be within plus or minus 5% of the figure that would be returned for our theoretical population of 12,000 UKCP members as a whole.

Some indication of how representative the sample might be of the wider profession comes from the gender breakdown of respondent swhich was female (79%), male (18%) and (3%) ‘other’. These figures correspond quite closely to the gender breakdown reported in the 2016 UKCP membership survey where the figures were female (74%), male (24%) and ‘preferred not to say’ (2%) (UKCP, 2016). So, in terms of gender breakdown, the sample in the current survey appears well aligned with the wider practitioner body.

Responses covered a diverse range of self‐reported modalities. By far, the largest grouping was for respondents who identified themselves as integrative (43%). Next were those identifying as person‐centred (9%). Other modality groupings were transactional analysis (8%), cognitive behaviour therapy (7%), psychodynamic (7%), existential (6%), gestalt (5%), humanistic (5%) and pluralist (2%). An ‘other’ category (8%) included systemic, psychoanalytic, transpersonal, psychosynthesis, core process, human givens and Ericksonian solution‐focused.

Respondents were asked how long they had been a practising therapist (in years); there were four different intervals shown in the survey, and the distribution of responses is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of years as a practising therapist

| Years as a therapist | % of responses |

|---|---|

| 1–4 | 23.0 |

| 5–8 | 18.0 |

| 9–12 | 16.0 |

| 12+ | 43.0 |

In terms of years practising as a therapist, the majority were those with 12+ years of experience who were almost twice as numerous as those with 1–4 years of clinical experience.

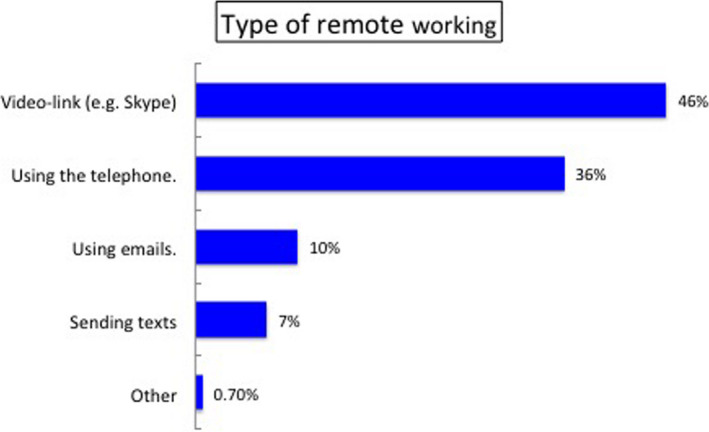

The first item in the survey asked respondents what types of remote working they had been using with clients. This was a multiple response question with respondents able to choose more than one response option. For analysis purposes, question response percentages were calculated for the total number of responses recorded, so that individual percentages will total 100%. The data pattern for type of remote working is shown in Figure 1, which indicates that the use of video link (46%) and telephone (36%) were by far the most popular types of remote working. The ‘other’ response group included instant messaging (e.g., WhatsApp) and sending letters to clients.

Figure 1.

Type of remote working used by therapists [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

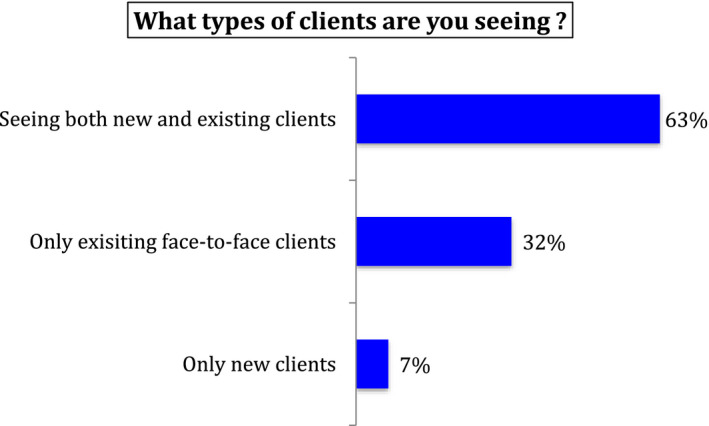

Survey respondents were asked whether they were seeing clients remotely, and whether (a) they had previously seen them face to face, (b) they were only seeing new clients remotely, or (c) they were seeing both new and existing clients by remote means. This was a multiple response question with respondents able to choose more than one response category. The data are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Type of client being seen remotely [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

From Figure 2, it is clear that most therapists were working remotely with both clients that they had previously seen face to face and with new clients (63% of all responses). However, it is noteworthy that nearly a third indicated that they were only seeing existing clients that they had already worked with face to face (32%).

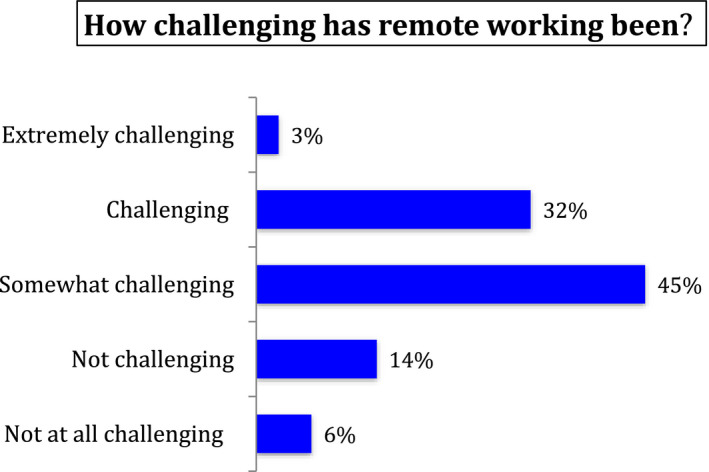

Survey respondents were asked how challenging they had found working remotely with clients. The response pattern is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

How challenging has remote working been? [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

From Figure 3, it can be seen that 35% of therapists found remote working with clients to be either extremely challenging (3%) or challenging (32%). A further 45% responded with the response category somewhat challenging. Only 20% reported that they found working remotely with clients was not challenging.

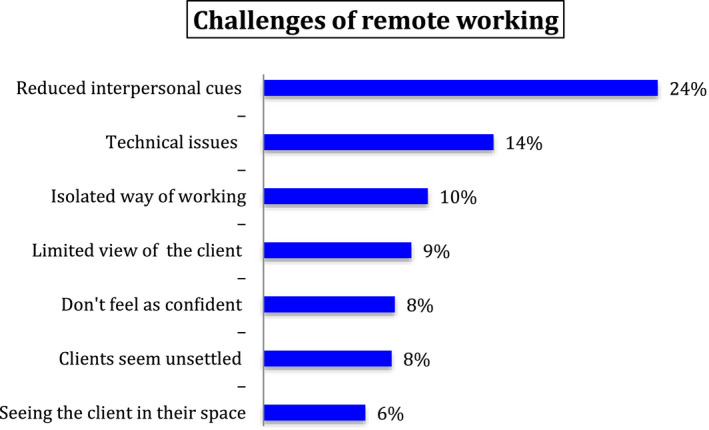

In a multiple response question, survey respondents had the opportunity to indicate why they found remote working with clients to be challenging. Respondents could choose more than one answer; the data shown in Figure 4 records percentages for answers that accounted individually for more than 5% of all responses.

Figure 4.

Why therapists found remote working challenging? [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

By far, the most frequent reason that therapists found remote working challenging was a perceived reduction in interpersonal cues (24%). This was followed by technical issues (14%) and a perception that remote working is an isolated or lonely way of practising (10%). A reduced perception of the client was again identified as challenging by 9% of responses recorded for the response choice limited view of the client. A reduced feeling of confidence was a response choice associated with 8% of all responses. A further 8% of responses were associated with a perception that clients seem unsettled.

Some of the remaining reasons why therapists felt challenged by remote working (as a percentage of all responses) included seeing the client in their own space (6%), finding the ending of remote sessions awkward (5%), and worrying that remote sessions could be accessed/hacked by a third party (5%).

In considering the challenges of remote working, a significant number of therapists chose to add free‐text comments in the other response category; there were 64 individual contributions, which is 19% of the total sample. Within this number, there were discernible clusters of similar expressions or themes. For example, several respondents talked of how tiring remote working had been and the intensity of concentration required. Several other therapists expressed concerns about client safety and worrying about potential unseen client distress after remote sessions had ended. Other therapists talked of a lack of embodied sense of presence and of the client. Likewise, there was an articulated sense that in remote working, the ‘transformational space’ is missing. Other comments referenced difficulties maintaining boundaries, and two therapists specifically talked about the difficulties they experienced when attempting to use EMDR techniques remotely.

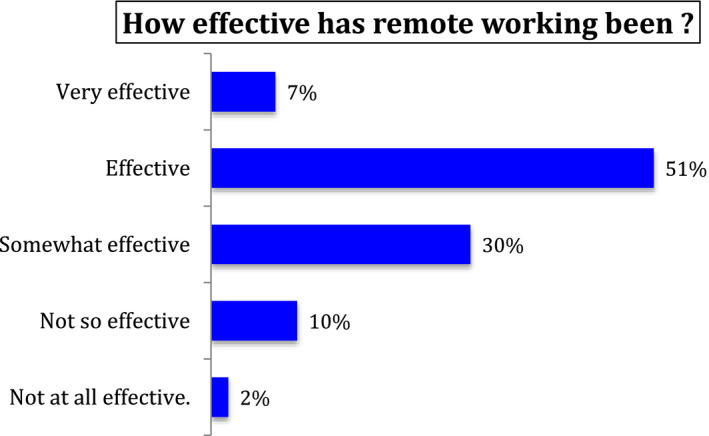

Survey respondents were asked how effective they felt, as a therapist, when compared to face‐to‐face working with clients. The data are displayed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

How effective therapists felt compared to face‐to‐face working? [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

A clear majority of therapists indicated that they felt effective as a therapist working remotely when compared to their experience of face‐to‐face working: 7% felt very effective, and 51% felt effective. A further 30% indicated that they felt somewhat effective. Only 12% indicated that they felt they were not effective, with 10% reporting they were not so effective and 2% ticking the box for not at all effective.

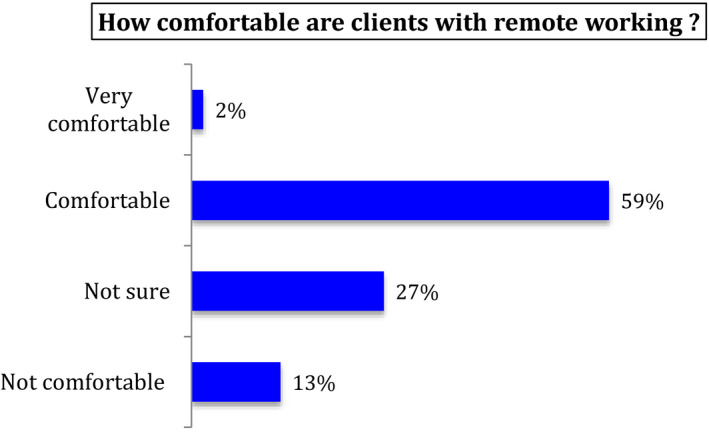

Survey respondents were asked how they thought their clients felt about working remotely. Therapists were asked how comfortable they felt their clients were about remote working. The relevant data are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

How comfortable are clients with remote working? [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 6 shows 61% of participating therapists felt that their clients were comfortable with remote working. However, the remaining 40% indicated that they were either not sure that their clients were comfortable with remote working (27%) or were of the opinion that their clients were not comfortable with remote working (13%).

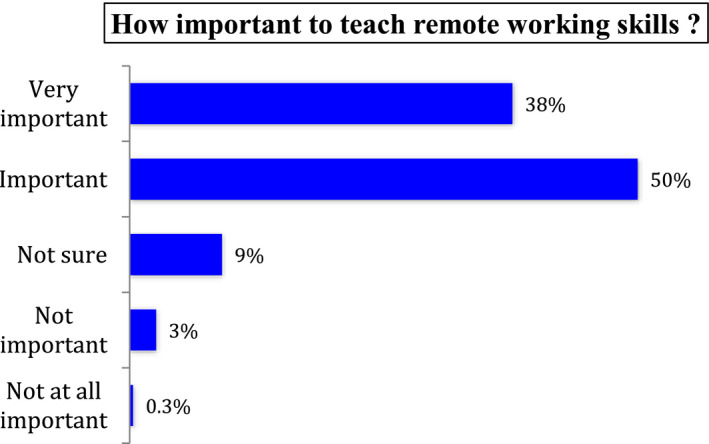

Survey respondents were asked how important they thought it would be for remote therapy skills to be a core subject of formal psychotherapy trainings. The data are shown in Figure 7, which clearly shows that the vast majority of therapists (88%) consider that it is either very important (38%) or important (50%) to formally teach remote working skills in therapy trainings. With 9% unsure, only 3.3% did not think it was important to teach remote working skills.

Figure 7.

How important is it to teach remote working skills? [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

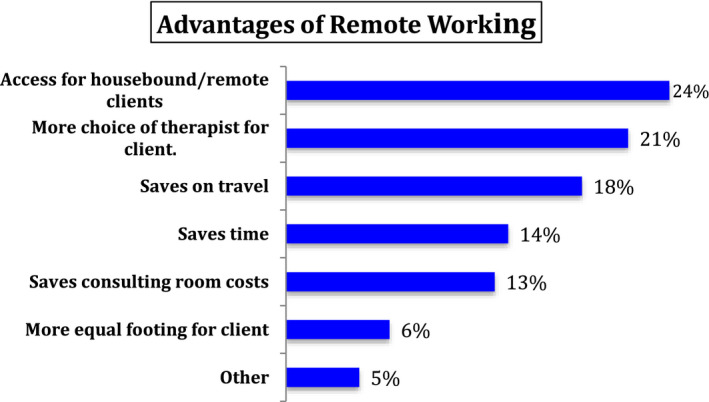

Survey respondents were asked what the advantages of remote working might be. This was a multiple‐choice question and so more than one choice from a fixed set of response choices could be made. The percentages are calculated from the total of all responses. Figure 8 shows the responses to a fixed set of response choices.

Figure 8.

Advantages of remote working [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The main advantages seen in remote working were that it provided better access to therapy for housebound clients or those living in remote areas (24%), gave clients a wider choice of therapist (21%), and allowed them to avoid spending time travelling to sessions (18%).

In considering the potential advantages of remote working, 55 therapists (16% of the total sample) chose to add free‐text comments in the ‘other’ response category. The most common thread was a sense that remote working allowed clients to feel more secure in their homes, and this was seen as a positive therapeutic factor. Other therapists commented that they were parents and that they had found working remotely was helpful for them in terms of child care. There was an overarching theme, expressed in various terms, that one of the main advantages of remote working is the flexibility that it offers therapists.

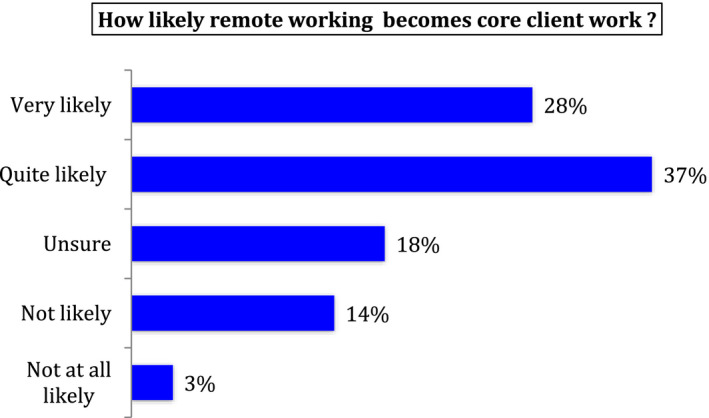

The final survey question asked respondents how likely it was that remote working would now become a core element of their clinical practice in the future and beyond the pandemic. The data are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

How likely remote working becomes core client work? [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Nearly two‐thirds of therapists thought it was likely that remote working would become core client work in the future with 28% very likely and 37% quite likely; a further 18% were unsure. The percentages for not likely and not at all likely were 14% and 3%, respectively.

8. FINDINGS: QUALITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

The survey respondents gave a total of 225 free‐text comments: these included statements of clarification, brief comments about a range of issues and, in some instances, a paragraph or more containing quite detailed accounts of personal experiences and reflection, amplifying considerably some of the issues highlighted in the survey. The total word count from the 225 free‐text comments was 9,051. This body of information and knowledge was recognised and treated as a relevant and valuable source of qualitative data and was subject to a thematic analysis.

9. REFLEXIVE THEMATIC ANALYSIS

Thematic analysis is a broad term that covers a range of approaches, which ultimately seek to find meaning across data sets. In exploring the qualitative data from the survey, the procedure adopted was informed by the particular approach articulated by Braun and Clarke (2006, 2019) called reflexive thematic analysis (RTA).

Braun and Clarke (2006) emphasise that reflexive thematic analysis is a method rather than a methodology, and as such, it is not aligned with any specific theoretical framework. It can therefore be applied using a range of different theoretical frameworks. To amplify this point, Braun and Clarke (2006) state that RTA can be a realist method, a constructivist method or a method aligned with critical realism. They place a strong emphasis on the researcher being an active creator of knowledge and reject any quasi‐positivist notion that themes and meanings simply emerge from the data as if they somehow pre‐existed.

The key underpinnings of reflexive thematic analysis are summarised by Clarke and Braun (2018) as follows:

We intended our approach to TA [thematic analysis] to be a fully qualitative one. That is, one in which qualitative techniques are underpinned by a distinctly qualitative research philosophy that emphasises, for example, researcher subjectivity as a resource (rather than a problem to be managed), the importance of reflexivity and the situated and contextual nature of meaning. (p. 107)

Clarke and Braun (2018) emphasise that in their version of thematic analysis, themes are more than a holding device for pieces of information; rather, they serve ‘as key characters in the story we are telling about the data’ (p. 108). A similarly significant emphasis is also placed on the potential for reflexive thematic analysis to move beyond description and summary. Clarke and Braun state that, ‘rich analysis typically moves from simple summation‐based description into interpretation; telling a story about the “so what” of the data’. (p. 109).

The theoretical flexibility of RTA means that it can be utilised to ask different sorts of research questions. For example, it can operate in a deductive way where themes are constructed from the data, or in an inductive way where theme development is guided by existing ideas and concepts. The method can also function in a constructivist manner where the focus is on how meaning is created. There is also a potential alignment with a critical realist position where the focus is on an assumed reality evident in the data.

The practical steps of the thematic analysis that we embarked upon for this study were, stepwise, relatively straightforward:

Data immersion, which involves intimate familiarisation with the data.

Preliminary coding, guided by a focus on ideas and issues that are then assigned a unique identity, for instance colour coding.

Reading and re‐reading to ‘firm up’ on the preliminary coding and challenge earlier meanings in context of new readings.

Clustering and creation of themes from codes to a broader, higher order of meaning.

Data saturation, reached when no new codes or themes become apparent.

Review of themes, individually and within the research team to confirm whether they remain meaningful and stable.

Writing up the themes, as a final element in meaning‐making.

The quantitative analysis was conducted by one team member, leaving the remaining two co‐authors to conduct the thematic analysis on the qualitative data provided from the survey. Each read the comments, suggested main and subthemes that were then compared, and discussed and agreed on.

10. THEMATIC ANALYSIS OUTCOMES

The survey offered a number of opportunities for free comment—participants were asked to comment on the challenges of remote working and on the advantages of remote working. They could also choose to provide further information via a free comment box at the end of the survey. A total of 225 free‐text comments were received: 64 with regard to ‘challenges’ of remote working, 55 about ‘advantages’ of remote working and 106 in the final free‐text comment box. While respondents could use any or none of these opportunities to comment, approximately a third of the survey respondents did add information using these fields, and the majority of comments made in the final free comment box were rich, detailed and comprehensive. To our surprise, the responses were overwhelmingly positive to the recent transition, evidencing a considerable resourcefulness and positivity. Out of 106 free comments, only four were negative, while others describe how respondents were adapting and becoming acclimatised to something which originally was not their choice.

We have arranged the emerging themes across the categories ‘adaption issues’, ‘opportunities’ and ‘challenges’. Within those categories, we identified different subthemes:

11. ADAPTION ISSUES

The majority of respondents did not have previous experience of working remotely. For these therapists, the sudden change presented a number of practical challenges. Some therapists made comments such as:

Digital counselling does not afford me the same level of job satisfaction.

More comprehensive comments not only indicated that this perceived loss of job satisfaction was related to initial technical difficulties, but also suggested that relational considerations were as, if not more, important to these therapists. Several said they found anxiety about connection problems and time lags between visual images and sound impacted on their ability to engage with clients. Others commented on how they found the experience of online as against face‐to‐face work different:

It is strange to have more intimacy on one level ‐ could almost touch on screen and in our own homes, and distant on another level, two dimensional disembodied clients are harder to relate to.

Several therapists reported physical difficulties with using technology:

As someone who is hard of hearing, moving to online work is challenging, particularly if the technology is not robust enough, and I find I have to concentrate even harder to listen.

A number of therapists spoke about the challenge of establishing a private space within their home from which to work. One therapist noted the physical strain on the body, particularly the head, neck and shoulders, when using Skype or Zoom. Another therapist experienced an ‘ethical issue’ with ‘online work because it encourages avoiding real meetings’.

Approximately a third of respondents reported that they were already using online platforms to deliver therapy. Of these, several indicated that their experience was quite limited, but that they had become more confident when they noticed that clients were able to work successfully in this way:

I was initially quite anxious/unsure about working online with my clients as I didn't have a lot of experience of this way of working. However, most of my clients have been open to exploring their feelings about working online and I have been surprised at the territory that some of them have been able to move into once we have settled into working in this way.

In some instances, it seems that dealing with working using a new medium democratised the therapeutic alliance as technologically informed clients were able to assist the therapist:

Some of my clients are finding that giving me help with the technology is empowering.

A small minority of respondents had extensive experience of working online and were motivated to do more online:

I used Skype and Zoom for some time before C‐19. Sometimes for clients who specifically wanted access to HG therapy and were too far away to access. Sometimes with historic clients now living and working in other countries. Sometimes with children who's visit to my therapy office would take too much school time out of there day (so I see them online at say 4pm or 6pm once they're home). I've had a private practice ….and occasionally see clients in my home office. After 8 years of seeing clients predominantly face to face, I'm now considering changing my marketing to do 90% online and just 10% face‐to‐face from my home office. It's the push I've been looking for.

One therapist worked online in regular practice, and found the way the term ‘online’ had been used in the context of the pandemic too limited since it:

…seems to refer only to working via video. As someone who has a qualification in online therapy, this is a misnomer. Video and text based forms of online therapy are very different, with video being more like face to face. For text based forms (email and synchronous chat forms), where client and therapist do not see each other, full training is vital and I would say it can be dangerous to operate without it.

A number of therapists said that overall—often contrary to their own expectations—they had had positive experiences. One therapist said for instance:

I don't think it is ideal as I would say face‐to‐face is the gold standard, but I have been surprised at how effective it has been ‐ with both individuals and couples.

Another captures some of the resourcefulness and openness to adapt which characterises many responses:

I have found that although working online using Zoom was initially difficult, like most things, it has become more manageable over the six weeks of doing it, and I have worked out what is useful/not useful, how to manage my self‐care.

Self‐care was reported as an issue by a number of respondents. They described how they had learned to adapt to their new working conditions in various ways by developing coping strategies such as creating spaces between sessions and seeing fewer clients per day; engaging in more and different forms of exercise to ‘alleviate tension and anxiety’; and taking up different forms of social interaction:

Working online is very intense, or at least it has seemed to me. Exercise has been very important in order to discharge some of the anxiety ‐ both my own and that of my clients.

And:

I very seldom write poetry and have not done so for over a decade, but this last week wrote a reasonably good one about a patient. I suspect it has to do with my way of coping with stress arising from remote work.

One therapist described missing ‘going to the pub to see my mates’ but referred to new online‐based means of meeting up with friends and colleagues, which helped to alleviate feelings of isolation.

Some therapists seemed to be in their element working online and were taking the opportunity to hone their skills:

I am constantly updating how I work remotely ‐ trying different platforms Googlemeets/Zoom as well as Skype/Facetime and phone. Updating technology ‐ wireless ear buds so I can charge phone/ipad at same time; new iPad Pro which has capacity to use whiteboard and Apple pen… Changing my room around for comfortable seating & standing sometimes…

Several therapists reported that adoption of online ways of working had inspired them to think more creatively about their knowledge and skills. One therapist wrote that that they had discovered that:

…working remotely has opened me up to the worlds of media, theatre, film, and movement as communication. My training and background in somatics has come in very handy in shifting from face‐to‐face work to online therapy. The more I learn about elements of theatre or film (set design/location, lighting, camera angle, sound), the more creatively I can configure the situation to support dynamic contact with my clients. The more I learn about the importance of space, posture, gesture, movement quality and how to employ these elements within the frame of the computer interface, the less intrusive the media interface becomes, and the more genuinely I can engage with clients and they with me.

12. OPPORTUNITIES

While it was clear that therapists’ experiences with adopting online ways of working varied, a clear majority report positive effects and outcomes of the remote working situations. Some refer to ‘opportunities’ and note the practical benefits that working online brings them, particularly when they have family commitments:

Coronavirus has made me shift my entire practice to online work. This has had the advantage that I can also work as the main carer for my mother.

A number of therapists note that online working removes the need for therapist and client to be geographically near:

Most of my work was already on Zoom/Skype. This was due to frequent travel and requests for therapy/supervision through connections overseas.

And:

I moved from London to the countryside recently and had to stop working with most of my established clients since they wanted to work face‐to‐face. Most of them have got in contact again now face‐to‐face isn't an option, and I’m finding we are able to reconnect without much difficulty.

One therapist noted:

…new clients who are interested in online therapy connect much faster with their therapist and the process of therapy and therefore there is very little difference between face to face sessions and online therapy with these clients. Regarding existing clients who are only familiar with face to face therapy: this presents as a mixed bag.

Several report positive reactions from their clients. One therapist refers, for instance, to clients showing less inhibition when working online:

Online therapy makes clients less inhibited (clients seem less consciously aware of their body language, facial gestures) which has allowed more material to come into the sessions.

And:

I feel that clients often open up more quickly working this way as they're in the safety of their own home and feel less awkward about sharing details that may have taken a few sessions to elicit in a face to face clinic setting.

Others refer to a power balance shift as the client can feel more able to leave the session if they wish to do so. The screen and the setting allowed for different forms of connection. One therapist goes as far as suggesting the online setting offers ‘more intimacy (on one level) could almost touch on screen and in our own homes’.

Other therapists resonate with this, describing how ‘working online at this time can actually bring some heightened sense of connectedness between client and therapist as working from one another's homes’.

Another therapist agrees, suggesting that:

The majority described, as mentioned to our surprise, a relatively smooth and rewarding transition:

…most of my clients have been open to exploring their feelings about working online and I have been surprised at the territory that some of them have been able to move into.

Several referred to positive, new learning—both about self‐ and therapeutic practice. One therapist said:

I have found the online work very interesting in terms of what I have noticed about myself in the work as well as how deeply I have been able to work with client.

A number of therapists said that working online expands therapeutic options: there are some highly specialised modalities and specialties that are easier to find with online therapists, and as one therapist expressed it: ‘For some conditions ‐ like agoraphobia this is a Godsend.’

13. CHALLENGES

Technical issues often provide the focus among those respondents who expand on problems. One therapist said: ‘The technical issues ‐ log in video is hard, it makes me prefer face‐to‐face’. With the exception of one therapist who noted ‘Some older clients don't have the technology or live in remote country locations with limited broadband’, respondents said little about any issues with technology that their clients might be experiencing.

A number of therapists referred to the practicality of having people/family around, for both therapists and clients. One therapist said:

I have really noticed how hard it is to move from therapist mode to parent‐mode by merely walking through a door (as opposed to having a journey home in a car or public transport)!

Others said:

Some of my clients have felt unable to engage with anything more than a weekly check‐in because they, too, have children at home, and they don't want to risk becoming upset in the home environment.

Some clients have no confidential space to talk in or indeed are living with the person who is the main problem or seems to be in their life and they find it difficult to talk knowing that person is nearby.

One therapist was an EMDR practitioner, and she reflected on possible challenges providing this online. Others noted that those therapies and therapeutic techniques that may include movement or working with objects or creating art are difficult to deliver online.

Many therapists referred to fatigue as a major problem. One therapist said: ‘Working online is more tiring for the therapist, I need more breaks’. Another resonated with this: ‘I have had to spread my clients out over another day ‐ working online is very intense.’

Many referred to a heightened sense of intensity from working via screen, and some referred to a sense of ‘disembodied’ clients. One said:

On the screen you work with two dimensional disembodied clients who are harder to relate to.

This formed part of a strain from having to make meaning in new ways, with little prior framing to fall back on—for instance in terms of relational framing. One said:

It seems now that my body and other senses must be doing half the work that I now have to do just by looking at a poor quality image, and a slightly delayed sound.

Another therapist echoed this and struggled to get a sense of the other in the absence of an embodied presence and with fewer non‐verbal cues:

It's difficult to ‘feel the other’ ‐ which often makes [therapists) work harder and more cognitively than when they are with their clients face to face.

This was manifested, for instance, in difficulty with being silent together. One therapist said: ‘another problem is to be with silence, there's a need to "fill" the space’. Therapists reported that they found they needed to make more effort to frame and make sense of the client's experiences. While this was sometimes transformational, it was often also very challenging. One therapist shared her grappling with making sense within her previous modality, and recounted how she tried to:

…link between the emotional state of my client and the state of my screen. For example, a client started the session in a panicky state (fearful inner child) and the screen was fuzzy. I engaged her adult and the screen became clear. Some other times, when the client's emotional state has been very strong, the Skype session has disconnected. When I see ‘poor connection’ coming up, I have learnt to tread carefully and possibly suggest we talk about something different. This has helped.

Another therapist suggested the supposed benefits of remote therapy, such as removing the need for clients to travel:

…removes opportunities to assess their motivation to engage with therapy and is perpetuating an unrealistically unhelpful message ‐ that all of life's difficulties and obstacles need to be removed; my learning from psychotherapy is that learning how to cope with life's difficulties is much more helpful than avoiding or removing them.

Another therapist felt that there was a danger of suggesting online and face to face are equivalent:

I fundamentally don't think it is, as the right brain connection and cues are more intense in 3D. I think often clients may ask for remote work as they feel less challenged by it, particularly younger clients (the ones I had definitely), and I think it's important then to clearly discuss what they might be missing out on, or even to insist they attend in person. I would definitely not want to run a whole practice of remote work, as I see it more as a compromise or an interesting add‐on, but not as a substitute for 'proper' therapy…

Finally, a shared problem for some therapists concerned the transition of previous long‐term face‐to‐face clients. At least three therapists chose to pause their therapeutic work. One therapist said:

I didn't continue with existing clients as I felt my usual way of conducting sessions was not conducive to working remotely.

14. CRITICAL EVALUATION

The purposive sampling methodology used in the survey could have been a potential source of bias because it is a non‐random approach, and therefore, individuals within the sample did not have an equal probability of being selected. However, it has to be considered that there are few other options to successively achieve a homogeneous group of psychotherapists for research purposes. There is understandably no access to the membership databases of professional bodies such as BACP and UKCP and so that prevents the use of a random sampling technique.

Even on those occasions when the professional bodies run their own surveys such as annual membership surveys, there is still the risk of bias. Specifically, there is the risk of non‐response bias, which refers to the possibility that survey data are skewed because those who responded to the survey are distinctly different from those who did not. So, in pursuing worthwhile research objectives that involve numbers of participants, there has to be a degree of pragmatism involved. Smith and Osborn (2008) make a key point in stating that ‘it should be remembered that one always has to be pragmatic when doing research; one's sample will in part be defined by who is prepared to be included in it’ (p. 56).

There is little doubt that one limitation of the research and one that indirectly influenced the content of the survey was the clinical situation of the author who drafted the survey. As a practising psychotherapist and member of a consultancy team of therapeutic practitioners who had to abruptly change to remote working and leave an established business premises, the immediate focus was on problem‐solving and, in addition, was the experience of seeing client numbers quickly decline. So, at that stage of the research it seems reasonable to suggest that a focus on opportunities for potential growth and the acquisition of new skills was somewhat inhibited. Research always takes place in a live context; at the time that the survey was conceived and designed, the live context was filled with uncertainty.

In reviewing the content of the survey, it could be suggested that it did not offer respondents sufficient opportunity to comment on the gravity of the coronavirus outbreak and the personal impact it may have had on therapists as individuals. Once again, this situation is probably revealing of the preoccupations of the author leading on the survey, but, for the most part, the survey worked well and received validation from many participants.

15. OVERVIEW AND SUMMARY

The research has produced a range of findings, both quantitative and qualitative, that clearly reveal some of the significant impacts and challenges that the coronavirus pandemic has had on practising psychotherapists. The extremely rapid change from face‐to‐face working to remote working with clients has exposed psychotherapists to a range of new and testing circumstances. For some therapists, the change in working practices has engendered uncertainty over their clinical effectiveness and the well‐being of their clients, and some have undoubtedly felt de‐skilled.

From both quantitative and qualitative data, it is clear that remote working has changed the therapeutic experience for psychotherapists. The therapeutic field and space has changed, as has the range of possible physical, embodied and psychological dynamics. Looking to the future and beyond the pandemic, there is a sense that the practice of psychotherapy has been profoundly and lastingly changed. In this regard, many therapists expect remote working to become part of their core service to clients in the future and a majority feel that remote working skills should now become a core subject of psychotherapy trainings.

For many therapists, the research confirms that the current coronavirus pandemic has required them to significantly adapt their ways of working and thinking to ensure that their clients can receive effective therapy. They have had to face the many challenges of reconfiguring the relational and personal dynamics of the therapeutic alliance. Overall, therapists have responded positively and with fortitude and imagination to safeguard the well‐being of their clients and themselves.

Biographies

Alistair McBeath is a BPS chartered psychologist and UKCP registered psychotherapist. He is a senior practitioner and founding member of the BPS register of psychologists specialising in psychotherapy and is a research supervisor at the Metanoia Institute.

Simon du Plock works as Faculty Head for the Faculty of Post‐Qualification and Professional Doctorates at the Metanoia Institute. He is a BPS chartered psychologist, senior practitioner and founding member of the BPS register of psychologists specialising in psychotherapy.

Sofie Bager ‐ Charleson is a Programme Director for the PhD in Psychotherapy at the Metanoia Institute. She is an integrative psychotherapist and supervisor with a special interest in practice‐based research.

McBeath A G, du Plock S, Bager Charleson S. The challenges and experiences of psychotherapists working remotely during the coronavirus pandemic. Couns Psychother Res. 2020;20:394–405. 10.1002/capr.12326

Coronavirus is the name for a family of viruses. COVID‐19 is a disease caused by a new strain of coronavirus. COVID‐19 was given the interim name 2019‐nCOV by the World Health Organisation (January 2020).

ENDNOTE

UKCP (2019) Annual review of accreditation 2019/20.

REFERENCES

- Asmundson, G. , & Taylor, S. (2020). Coronaphobia: Fear and the 2019‐nCoV outbreak. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 70, 102196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bager‐Charleson, S. , McBeath, A. G. , & du Plock, S. (2019). The relationship between psychotherapy practice and research: A mixed‐methods exploration of practitioners’ views. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19, 195–205. 10.1002/capr.12196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Y. , Sun, Y. , Meng, S. , Shi, J. , & Lu, L. (2020). 2019‐nCoV epidemic: Address mental health care to empower society. The Lancet Journal, 395(10224), e37–e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentall, R. (2020). Covid‐19 Psychological Research Consortium. Initial findings on COVID‐19 and mental health in the UK. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1A95KvikwK32ZAX387nGPNBCnoFktdumm/view [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, R. (1978). A realist theory of science, 2nd. Brighton: Harvester Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, R. (1979). The possibility of naturalism. Brighton: Harvester Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. (2020). How are counsellors coping with Covid‐19? Therapy Today 31(4), 16–20. 5p., Database: Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V. , & Braun, V. (2018). Using thematic analysis in counselling and psychotherapy research: A critical reflection. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 18(2), 107–110. 10.1002/capr.12165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danermark, D. , Ekström, M. , Jakobsen, L. , & Karlsson, J. (2002). Explaining society: An introduction to critical realism in the social sciences (Critical realism: Interventions). London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse‐Biber, S. (2010). Mixed methods research: Merging theory with practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Landrum, B. , & Garza, G. (2015). Mending fences: Defining the domains and approaches of quantitative and qualitative research. Qualitative Psychology, 2(2), 199–209. 10.1037/qup0000030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liddon, L. , Kingerlee, R. , & Barry, J. A. (2017). Gender differences in preferences for psychological treatment, coping strategies, and triggers to help‐seeking. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(1), 42–58. 10.1111/bjc.12147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund, T. (2005). The qualitative‐quantitative distinction: Some comments. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 49(2), 115–132. 10.1080/00313830500048790 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McBeath, A. (2019). The motivations of psychotherapists: An in‐depth survey. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19(4), 377–387. 10.1002/capr.12225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McBeath, A. G. , Bager‐Charleson, S. , & Abarbanel, A. (2019). Therapists and Academic Writing: "Once upon a time psychotherapy practitioners and researchers were the same people". European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy, 19, 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy, P. , & Richards, D. (2003). Critical realism: A way forward for evaluation research in nursing? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 43(4), 411–420. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02730.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potash, J. S. , Kalmanowitz, D. , Fung, I. , Anand, S. , & Miller, G. (2020). Art therapy in pandemics: Lessons for covid‐19. Art Therapy Journal. 10.1080/07421656.2020.1754047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reicher, S. , Drury, J. , & Stott, C. (2020). The two psychologies of coronavirus. The Psychologist, 1p. https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/two‐psychologies‐and‐coronavirus [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. A. , & Osborn, S. (2008). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In Smith J. A. (Ed.), Qualitative psychology (pp. 53–80). London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- UKCP (2019). Annual review of accreditation 2019/20. Retrieved from https://www.professionalstandards.org.uk/docs/default‐source/accredited‐registers/panel‐decisions/ukcp‐annual‐review‐2019‐20.pdf?sfvrsn=7a7b7420_4 [Google Scholar]

- UKCP Membership Survey (2016). In Therapy Today, March 2017: Volume 28, Issue 2. Retrieved from https://www.bacp.co.uk/bacp‐journals/therapy‐today/2017/march‐2017/is‐counselling‐womens‐work/ [Google Scholar]

- Ukpabi, D. C. , Enyindah, C. W. , & Dapper, E. M. (2014). Who is winning the paradigm war? The futility of paradigm inflexibility in Administrative Sciences Research. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 16(7), 13–17. [Google Scholar]