Editor

Throughout March and April 2020, dermatologists have observed an outbreak of chilblains despite climatic conditions not conducive to their apparition. These lesions have occurred simultaneously to the COVID‐19 epidemic, suggesting a relationship between their onset and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

Here we describe a series of 10 patients presenting chilblain‐like lesions in whom we have searched for evidence of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

Between 17 and 29 April 2020, we have included patients successively referred to our Department for chilblain‐like lesions. Present and past medical history were recorded along with complete skin examination. Blood samples were collected for blood cell count, CRP, liver and renal parameters, antinuclear antibodies (anti‐ENA and anti‐DNA antibodies if positive immunofluorescence), complement components, ANCA, cryoglobulins, anti‐prothrombinase, anticardiolipin antibodies, coagulation factors and D‐dimers. Serological status concerning human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis viruses and SARS‐CoV‐2 were established using automated assays performed on an Abbott ARCHITECT i2000 (Abbott Diagnostics, Rungis, France). Two biopsies were performed on lesional skin for diagnosis by light microscope examination and for SARS‐CoV‐2 search by RT‐PCR test targeting the RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase gene (https://www.who.int/docs/default‐source/coronaviruse/real‐time‐rt‐pcr‐assays‐for‐the‐detection‐of‐sars‐cov‐2‐institut‐pasteur‐paris.pdf). We also searched for SARS‐CoV‐2 on a nasopharyngeal swab using RT‐PCR.

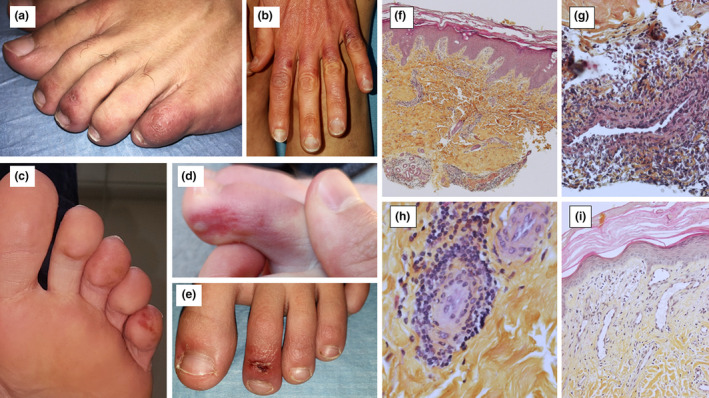

Ten patients were included [median age: 33 years (11–57), sex‐ratio 1 : 1]. All had erythematous, livedoid and purplish patches and papules on fingers or toes, evolving towards erosions, pigmentation and scaling (Fig. 1, Table 1). In eight patients, lesions began with a burning pain, which shifted towards pruritus in five patients. Lesions started 26.5 days prior to consultation (14–52) and healed within 35 days (27–45) without sequelae in seven patients. Five patients experienced short‐duration viral symptoms without fever, anosmia nor ageusia. None of them had contact with a confirmed COVID infected person. Biopsies showed (Fig. 1) inconstant epidermal lesions (apoptotic keratinocytes, epidermal necrosis, basal layer vacuolation, mild spongiosis and parakeratosis), an upper dermis oedema, and a perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Vascular lesions were prominent with angiocentrism, angiotropism and endothelium swelling, capillar ectasia and fibrinoid thrombi. All blood sample examinations were normal except for three patients who had positive antinuclear antibodies with anti‐nucleolar or anti‐centromere patterns. SARS‐CoV‐2 research on nasopharyngeal swabs and on skin biopsies was negative, and no SARS‐CoV‐2‐specific IgG was detected in any case.

Figure 1.

Skin lesions (a: Patient 7; b: Patient 9; c: Patient 10; d: Patient 4; e: Patient 3); Lesional skin biopsies, Haematoxylin, Eosin and Saffron (HES) (f: lymphohistiocytic infiltrate around vessels and eccrine glands, ×4 magnification; g: Angiocentric lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in superficial dermis, ×40 magnification; h: Angiotropism, ×40 magnification; i: Papillary dermis oedema, capillar ectasia and endothelial swelling, ×20 magnification).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patient | Medical history | Clinical examination | Biology | SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/Sex | Relevant past medical history | Associated viral symptoms | Time between 1st symptoms and consultation (days) | Skin symptoms duration to healing (days) | Clinical description | Topography | Antinuclear antibodies (titre) | SARS‐CoV‐2 serological status | Nasopharyngeal swab | Skin biopsy | |

| 1 | 60/F | Raynaud's disease | None | 28 | 38 | Purplish macule | Right index fingertip | Negative | Negative | / | Negative |

| 2 | 32/H | / | Asthenia | 25 | 35 | Erythematous and purplish patches and papules with superficial erosion | Dorsal side of the toes (right I, III, IV, V and left I, II, IV, V) | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 3 | 11/H | / | Asthenia, headaches | 28 | 27 | Erythematous purplish patches and papules with superficial erosion and post‐inflammatory scaling | Dorsal surface of the toes (both side I and II) | Negative | Negative | / | Negative |

| 4 | 18/H | / | None | 16 | 27 | Erythematous, livedoid and purplish patches and papules with superficial erosion | Dorsal and lateral sides of the toes (left I, II, III, V) and fingers |

Positive (1/640) anti‐centromere antibodies |

Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 5 | 34/F | Raynaud's disease, chilblains | None | 52 | >60 | Purplish and livedoid macules with post‐inflammatory scaling | Dorsal side and fingertips of the all toes |

Positive (1/2560) nucleolar fluorescence |

/ | Negative | Negative |

| 6 | 57/F | / | None | 14 | >60 | Purplish macules | All fingertips |

Positive (1/160) dense cytoplasmic fluorescence |

Negative | / | Negative |

| 7 | 24/H | / | None | 22 | 29 | Erythematous and purplish patches and papules with superficial erosion and post‐inflammatory scaling | Dorsal side of the toes (right III, IV, V and left II, IV, V) | Negative | Negative | Negative | / |

| 8 | 50/F | / | Asthenia | 37 | 45 | Purplish and livedoid patches | Toe fingertips (left I, II, III) | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 9 | 40/F | Raynaud's disease, chilblains | Headaches | 24 | >60 | Erythematous patches with post‐inflammatory scaling | Dorsal side of the fingers with respect of the interphalangeal joints ( right II, III, IV, V and left II, III, IV, V) | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 10 | 14/H | / | Cough, asthenia, headaches, myalgia, arthralgia | 35 | 43 | Erythematous, liveoid and purplish purplish patches and papules with post‐inflammatory pigmentation and scaling | Dorsal surface and fingertips of all toes | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

We present a series of 10 consecutive patients with typical clinical and pathological chilblains occurring during the peak of COVID‐19 infection. In our area, the weather was warm at that time and all patients lived under lockdown in well‐heated houses. In all patients, we failed to demonstrate neither a current nor recent COVID‐19 infection nor SARS‐CoV‐2 presence in skin. The absence of respiratory symptoms and the known rapid clearance of SARS‐CoV‐2 in moderate infections could explain the negativity of RT‐PCR analysis. The absence of specific IgG suggests that a reaction due to COVID‐19 is unlikely even though these patients could have only specific IgM. However, IgM peak between days 5 and 12 after infection 1 whereas IgG reach peak concentrations after day 20 and most patients were tested after 20 days of evolution of skin lesions. Furthermore, the sensitivity 2 of our test is 100% after day 17. Three of these patients had positive antinuclear antibodies suggesting an undiagnosed autoimmune disease (scleroderma or lupus) but no one presented other clinical symptoms.

Chilblain‐like lesions have been reported for several weeks 3 , 4 , 5 in patients COVID infected or not, suggesting that they could be induced by SARS‐CoV‐2. Our data do not confirm a direct role of SARS‐CoV‐2 or an immunological hit‐and‐run mechanism. Some of these patients might have an authentic systemic disease, fortuitously detected. To conclude, our results do not support a direct effect of SARS‐CoV‐2 in the observed outbreak of unusual chilblain lesions during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Conflicts of interest

None reported.

Funding source

None.

Author contributions

Dr Rouanet had full access to all of the data of the case series and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Rouanet and D'Incan. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Supervision: Rouanet and D'Incan.

Acknowledgements

The patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to the publication of their case details. We thank Dr Elodie DEVERS (Department of Dermatology), Dr Carole CHEVENET (Department of Pathology), Dr Anne‐Sophie MARCHESSEAU‐MERLIN, Dr François MICHEL and Dr Charlotte PIECH, (dermatologists), Pr Marc BERGER and Dr Juliette BERGER (CRB‐Auvergne), Pr Marc RUIVARD (Department of Internal Medicine) and Matthieu GEMBARA (manuscript proofreading).

References

- 1. Kontou PI, Braliou GG, Dimou NL, Nikolopoulos G, Bagos PG. Antibody tests in detecting SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a meta‐analysis. Diagnostics 2020; 10: 319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bryan A, Pepper G, Wener MH et al. Performance characteristics of the abbott architect SARS‐CoV‐2 IgG assay and seroprevalence in Boise, Idaho. J Clin Microbiol 2020. In press. 10.1128/JCM.00941-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Masson A, Bouaziz JD, Sulimovic L et al. Chilblains are a common cutaneous finding during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a retrospective nationwide study from France. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020. In press. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Galvan Casas C, Catala A, Carretero Hernandez G et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID‐19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol 2020. In press. 10.1111/bjd.19163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Piccolo V, Neri I, Filippeschi C et al. Chilblain‐like lesions during COVID‐19 epidemic: a preliminary study on 63 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020. In press. 10.1111/jdv.16526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]