Although the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus is thought to be spread mostly by droplets, there are situations such as tracheal intubation, extubation and non‐invasive ventilation where viral particles may be transmitted to healthcare workers by small airborne nuclei [1]. Of additional concern, turbulent gas clouds may carry droplets much further than the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or World Health Organization recommendations suggest [2]. A study from Wuhan, China, detected viral particles on surfaces and in air samples within the general ward and the intensive care unit (ICU) [3]. Notably, the ICU had higher positive rates compared with the general ward, suggesting that sicker patients, or the therapies they require, increase viral dispersion. Several barrier enclosures have recently been described for use during tracheal intubation and extubation of COVID‐19 patients [4, 5]. Whereas these enclosures contain visible fluorescent particles during simulated coughing, they increase the difficulty of the procedure by restricting movement, and there is insufficient evidence that such enclosures actually protect staff from viral spread. We set out to test whether simple physical barriers reduce the spread of small airborne particles and if the addition of negative airflow improves their effectiveness.

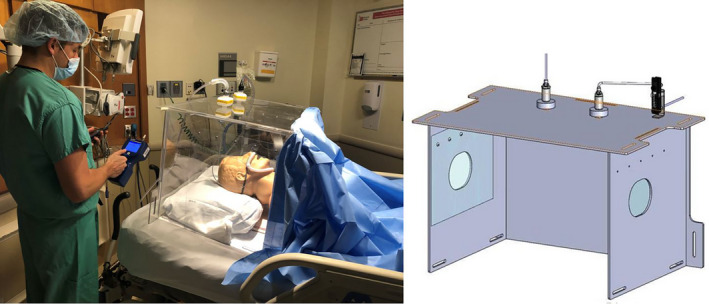

Our team constructed a transparent four‐sided polycarbonate enclosure similar to the design used by Canelli et al. [4]. The enclosure was modified with two wall suction connections through high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters on the top panel. Access holes were covered with 0.016‐inch thick plastic flaps and relocated to the sides in order to allow routine patient care. An adhesive surgical drape was used to cover the lower body (Fig. 1). We increased the dimensions of the enclosure to 67.5‐cm long, 50‐cm wide and 50‐cm high in order to accommodate larger patients and permit freedom to move inside. This allows patients to adjust their oxygen supply or suction themselves without a provider’s assistance. The chamber was secured to the bed using quick release soft limb restraints. In such a way, the head of the bed could be raised.

Figure 1.

Photograph and diagram of polycarbonate enclosure with attached wall suction and HEPA filtration. Access holes on the sides were covered with clear plastic flaps and the torso of the simulated patient was covered with an adhesive surgical drape

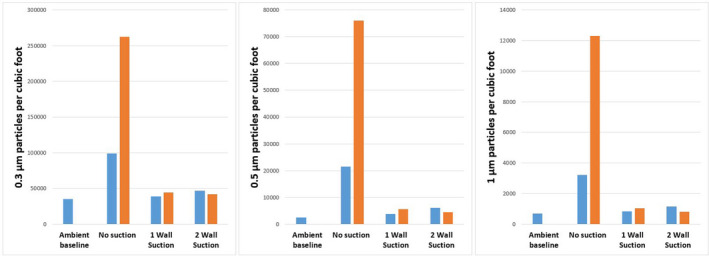

Although the size of the SARS‐COV‐2 virus is approximately 0.06‐0.12 microns, most viral particles are carried by aerosols measuring less than 4 microns. Of these, particles smaller than 1 micron remain suspended longer in the air and are more difficult to filter [6]. We thus placed a particle generator (TSI Model 8026; TSI Inc., Shoreview, MN, USA) inside our enclosure and used a particle counter (TSI AeroTrak Model 9306‐V2; TSI Inc., Shoreview, MN, USA) to measure levels of 0.3, 0.5 and 1 micron particles in close proximity to the enclosure. Without any suction, particle detection outside the chamber increased many times above the ambient level after 5 min. However, when attached to one (55 l.min‐1) or two (100 l.min‐1) wall suction connections, particle increase was negligible (Fig. 2). During visual testing with fog (propylene glycol in de‐ionised water), leakage of fog outside the chamber was also greatly reduced when suction was applied to the enclosure.

Figure 2.

Number of 0.3, 0.5 and 1 micron particles per cubic foot detected outside the enclosure. Particle counts were measured at baseline, 1 min after (blue) and 5 min after (orange) release inside the enclosure

In conclusion, a simple enclosure may contain visible droplets, but is insufficient to protect against smaller aerosolised particles during simulated conditions. This was true even when a drape was placed over the opening for the torso and access holes were covered. However, when paired with wall suction and HEPA filtration, such an enclosure significantly decreased airborne particle spread into the room. In an environment with inadequate supplies of personal protective equipment and airborne isolation rooms, this inexpensive, reusable system may offer additional protection for bedside providers. Patients with severe COVID‐19 create aerosols in multiple clinical scenarios, including airway management, coughing, suctioning and the use of less invasive therapies for hypoxaemia. At times, the desire to use heated high‐flow oxygen or continuous positive airway pressure to avoid tracheal intubation conflicts with the imperative to protect healthcare workers. Successful containment of airborne particles may reconcile these goals by allowing the support of hypoxaemic patients without increasing the risk of exposure to infectious aerosols.

The Ohio State University Center for Design and Manufacturing Excellence helped design and manufacture the prototype enclosure. The Ohio State University College of Medicine Clinical Skills Education and Assessment Center provided facilities for testing. The Ohio State University Environmental Health and Safety Department provided equipment for particle measurement. The Center for Clinical Translational Science funded the construction of the prototype but had no part in the data collection or writing of the manuscript. No other competing interests declared.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID‐19: implications for IPC precaution recommendations. Scientific brief. 29 March 2020. https://www.who.int/news‐room/commentaries/detail/modes‐of‐transmission‐of‐virus‐causing‐covid‐19‐implications‐for‐ipc‐precaution‐recommendations (accessed 09/06/2020).

- 2. Bourouiba L. Turbulent gas clouds and respiratory pathogen emissions: potential implications for reducing transmission of COVID‐19. Journal of the American Medical Association 2020; 323: 1837–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guo Z‐D, Wang Z‐Y, Zhang S‐F, et al. Aerosol and surface distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in hospital wards, Wuhan, China, 2020. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2020; 26: 1583–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canelli R, Connor CW, Mauricio G, Nozari A, Ortega R. Barrier enclosure during endotracheal intubation. New England Journal of Medicine 2020; 382: 1957–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matava C, Yu J, Denning S. Clear plastic drapes may be effective at limiting aerosolization and droplet spray during extubation: implications for COVID‐19. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 2020; 67: 902–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simonds AK. ‘Led by the science’, evidence gaps, and the risks of aerosol transmission of SARS‐COV‐2. Resuscitation 2020; 152: 205–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]