Abstract

Drawing on the voice of a woman NHS front‐line doctor during the current COVID‐19 pandemic, we explore her lived experience of the embodiment of risk in the crisis. We explore her struggles and difficulties, giving her voice and mobilizing our writing to listen to these experiences, reflecting on them as a way of living our own feminist lives. Her story illustrates that the current crisis is not only a crisis of health, but a crisis for feminism. Through telling her story, we cast light upon the embodied amplification of inequalities, paternalistic discourses around risk and lived experience of exposure to risk of contracting a deadly virus. We explore her work on the NHS front line, providing a conceptual framework of the multi‐level facets of the embodiment of risk, through lived experiences of risk and observations of the inequality of risk in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic in the UK.

Keywords: COVID‐19, embodiment, gender, health services, risk

1. INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT

This piece draws on the story and voice of a woman front‐line NHS doctor who contracted COVID‐19 in the early stages of the pandemic. It situates the story as a glimmer of organizational practice amidst a public health (societal) crisis. It explores her lived experiences of and reflection on not only the work itself, but also: the discourses around risk; the embodied amplification of inequalities through equipment shortages and inadequacies according to their design for a ‘standard body’; and the emotions and coping mechanisms in these contexts.

We explore her struggles and difficulties, giving her voice, but specifically using our listening to her voice to mobilize our writing about the experiences as a way of living our own feminist lives. We bring to the fore empirical insight into a woman doctor’s experiences during the current pandemic to cast light on the lived experience of life and work ‘on the front line’ of COVID‐19 and reflect on the broader implications of this. We frame lived experience as socially constructed and deeply gendered. Even after over 30 years since West and Zimmerman’s (1987) seminal work, gender still remains ‘one of the most fundamental divisions of society’ (p. 126), and the ideal worker is still consistently constructed as male (Bruni, Gherardi, & Poggio, 2004). We further argue in this article that particularly in the context of COVID‐19, that this affects the discourses and embodiment of risk, and in turn, the inequality of risk, presenting a conceptual framework of the embodiment of risk during COVID‐19. The NHS workforce is predominantly women, albeit there is a clear vertical gender segregation, but the organization and its responses to risk, particularly in a time of crisis, are gendered masculine (Acker, 1990; Hearn, 2000; Williams, Muller, & Kilanski, 2012).

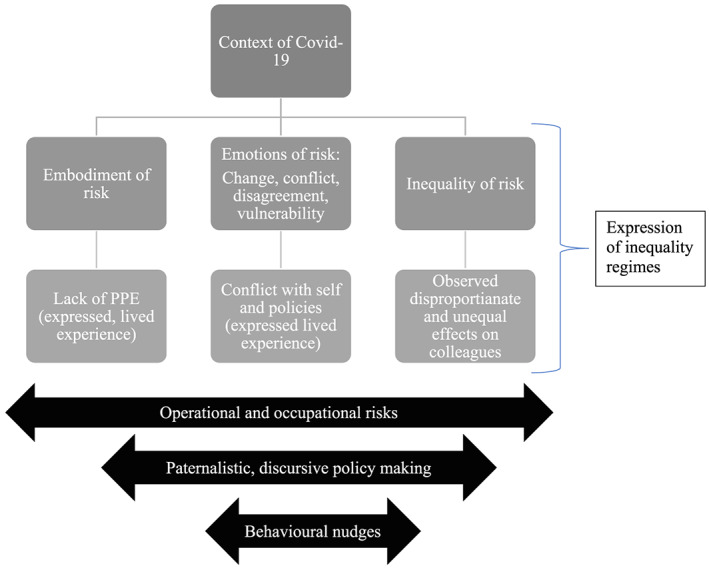

We draw on one, exploratory in‐depth, semi‐structured interview with an NHS doctor. The interview was conducted in line with all current government guidance and restrictions on direct social contact in order to limit the spread of COVID‐19, as at 2 June 2020. It was conducted in line with our institutions’ ethical guidelines. It is important to stress that the views expressed are of the doctor herself, and not the NHS or the NHS trust by which she is employed. It was recorded and transcribed in full, verbatim to aid analysis. The analysis of the interview has drawn on Alvesson and Sköldberg’s (2000) approach to reflexive interpretation, specifically in that this piece seeks to point out elements of interest rather than intending to be a complete or comprehensive set of analyses. There are many possibilities in the interpretation of the material and we present themes that occurred to us both as we interacted with the interview material, though we adopt a subjective interpretivist philosophical position, framing gender as socially constructed (Butler, 1990). As such, the piece that follows is structured to show a dialogue between the interview with the NHS doctor, us as researchers and relevant extant literature. It moves between all of these elements in the creation of a narrative, framed further by the concept of inequality regimes (Acker, 2006) and further illustrated in the conceptual framework we present (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework of the embodiment of risk during COVID‐19

The participant, who we call Louise, has been working on the front line throughout the COVID‐19 pandemic; though not on a COVID‐19‐specific ward or intensive care, albeit she has been in direct contact with COVID‐19 patients, in turn, contracting the virus herself. Excerpts from the interview explore lived experience, the emotional and physical toll not only of the COVID‐19 virus but also of struggles, resilience and reflection. We explore her experience of both working during the pandemic, and her own experience of contracting COVID‐19 and subsequently returning to work. Her voice is featured in italics throughout this piece.

This article is structured as follows: first, we briefly discuss COVID‐19 in the UK 1 context, though the research has been conducted with a doctor in England and so references to guidance and personal protective equipment (PPE) policy refer to those from Public Health England. We then explore the main facets of the embodiment of risk identified in the research. In our conceptual model (see Figure 1), we conceptualize and highlight the embodiment of risk, characterized by, and through, the reflections of the participant, focusing on core themes to enable a focus on the experiential account of the participant, Louise.

2. COVID‐19 IN THE [GENDERED] UK CONTEXT

It is important to situate this article in the context of the pandemic in the UK, which has been criticized globally not only for a laggard response to COVID‐19, but also for the political communications and handling of the UK government’s response, which may be described as morally moribund. A report published, although denied by Number 10, ‘quoted one anonymous senior Conservative as saying [of another senior advisor]: ‘He's gone from “herd immunity and let the old people die” to “let's shut down the country and the economy”’ (Walker, 2020). We further discuss the notion of herd immunity later with reference to the UK government’s policy approach to the COVID‐19 pandemic.

In the four months of the crisis to date, there is already evidence of the further entrenching and amplification of gender roles in the home, gendered ways of working and gendered caregiving roles during the pandemic (e.g., Hupkau & Petrongolo, 2020) and it is already clear that in the longer term, this is set to worsen. It is clear that the current health crisis is also a crisis for feminism (Mukhtar, 2020) in terms of the widening of previously narrowing inequalities in work–life practices. The following sections explore these, considering the intersection of policy and how this is then translated into organizational practices.

2.1. PPE — Politics, planning and embodiment?

It is possible to see inequalities in healthcare workplace practices that are particularly embodied (Kerfoot & Knights, 1993; Liu, 2017), both evident by the viscerally embodied nature of the virus and the embodied nature of the treatment of patients. The medical profession, indeed like many professions, is blighted by deeply ingrained vertical gender segregation (Crompton & Le Feuvre, 2003). Despite increases of women doctors since the 1970s, globally there is a fervent persistence of gender inequality in the medical profession (Riska, 2010). The NHS is the UK’s biggest employer and the fifth largest employer in the world (NHS Employers, 2016), and although being made up of around 80 per cent women, women are disproportionately represented in nursing roles (the largest professional group) and vastly underrepresented, for example, as surgeons, and further still at consultant surgeon level (Aldrich, 2019). Clearly, in the light of the current crisis, women’s lived experiences of working during a pandemic and the embodiment of [gendered] inequality and risk are vital.

The inequalities embedded in the decision‐making processes regarding the management of the crisis are manifest. Ultimately, this has been driven by Westminster, Boris Johnson as prime minister and SAGE (Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies). It is notable that the SAGE team is made up primarily of [white] men (16 men and seven women) and only one black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) expert. It is an indictment, given that COVID‐19 has been found to disproportionately affect and have a significantly higher mortality rate for BAME individuals (NHS England, 2020a) that there is only one BAME individual on this advisory group. These contextual factors set the scene for characteristic paternalistic discourse and paternalistic, discursive strategy making in crisis (Sibony, 2020), as well as, in turn, the intensification of gender performativity in the context of COVID‐19 (Hennekam & Shymko, 2020). Louise comments on her discussions between colleagues as follows:

Once it became more vague with this stay alert well then it just became a bit of a joke, there’s a lot of silly messages going around and just stuff made up, and I think it just was, we just talked about it being a political thing not a science‐based thing.

In this respect, policy making in the UK context surrounding COVID‐19 may be said to be based on epidemiology and behavioural sciences (Politico, 2020) as well as the notion of ‘behavioural fatigue’, whereby people would get bored of staying at home, thus rendering the lockdown ineffective (Sibony, 2020); indeed, the [current COVID‐19] ‘epidemic does not shut down politics’ (Sibony, 2020, p. 352) but, if anything, seems to have exacerbated political influence in decision‐making on scientific responses. Scenario planning for global health emergencies happens, with Louise reflecting on inadequacies in the planning process as follows:

You know, you can look back to the planning exercise they did I think back in 2016 and all the recommendations they had for equipment, and lo and behold we didn’t have it when this pandemic came.

The National Health Service was front and centre in the government communication regarding the earliest stages of the crisis, with instructions distilled to the ‘stay home, protect the NHS, save lives’ initial soundbite. This was supported by the ‘clap for carers’, an embodied display of (healthy) public support for those putting their lives at risk in the protection of us all. This, however, shifts the responsibility for ‘protecting the NHS’ to the public, for them (us) to reduce the risk and moving the discourse away from the deeply politicized nature of the funding and management of healthcare provision in the UK — that indeed, ‘lo and behold’, the requisite equipment had not been invested in. Louise reflects further:

there was a lot of evidence of community support groups being put up, a lot of people you know doing a lot more with supporting their neighbours, supporting vulnerable in the community, um people looking out for each other. And I think initially that was very strong, and that was something really, really nice to see, the community support towards the NHS, all the clapping and everything.

The structural decisions made at policy [macro political] level are translated into lived experiences of home and work. Whilst Louise recognizes the benefits of community cohesion generated through this crisis, she also comments that this is ‘too little too late’. We also saw evidence of our own communities keeping our bodies at home, offering support to one another and also to the NHS workers through making masks, mask extenders, donating millions of pounds to NHS charities and other material contributions to reduce the risks to the front‐line medical workers. The public has been filling gaps in structural investment. But then, as time has gone on and our own rule‐makers became rule‐breakers (e.g., Weaver, 2020), using our bodies to protect NHS bodies through the minimization of the risk of spreading the virus has become less of a focus. Louise expresses her frustration as follows:

I think we we’ve talked a lot about the fact that the public seemed to be on board before and we were working hard, the NHS, to keep, you know to keep the, to keep the curve under control, and the public were working hard to keep the curve flat and so we weren’t overwhelmed, and to get the numbers down, and we were creating more beds at all these new Nightingale hospitals and; that all felt good getting on top of it, but whether it’s just the general public running out of steam, whether it was messages weren’t clear anymore, it became really frustrating as healthcare professionals to be in the hospital working you know, seeing colleagues still getting ill, seeing patients still being ill, patients still dying, families still being impacted, and yet looking outside to see people flout, you know flouting the rules, not isolating, people meeting in groups etc., it became a bit insulting.

Linked to this, it is also of note to reflect upon the aforementioned notion of herd immunity in the socio‐political context of COVID‐19, the herd being the group of public bodies. Herd immunity refers to the notion that: Vaccination ideally protects susceptible populations at high risk for complications of the infection. However, vaccines for these subgroups do not always provide sufficient effectiveness. The herd effect or herd immunity is an attractive way to extend vaccine benefits beyond the directly targeted population. It refers to the indirect protection of unvaccinated persons, whereby an increase in the prevalence of immunity by the vaccine prevents circulation of infectious agents in susceptible populations. (Kim, Johnstone, & Loeb, 2011, p. 683). However, we mobilize the notion of herd immunity, as not only contested, but also critically as an antecedent for the behavioural nudges and behavioural science which typify the UK government’s policy approach to COVID‐19. This leads us to discuss the embodiment of risk in practice of front‐line medical workers, such as Louise.

3. THE EMBODIMENT OF RISK IN PRACTICE

In conceptualizing the notion of the embodiment of risk in practice, the embodiment of risk through emotion and the inequality of risk, we adopt the definition of risk management in health care from Cure, Zayas‐Castro, and Fabri (2014) which shifts the discourse from financial risk to ‘include risks related to patient care, medical staff, employees, and property’ (p. 89) in the context of risk‐based regulation (Beaussier, Demeritt, Griffiths, & Rothstein, 2016).

As such, whilst healthcare workers should be able to reduce these risks by wearing PPE as part of the responsibilities of the workplace as well as the agency of individual workers (Manne, 2019), this has been insufficient. During the crisis, there have been three main factors affecting the levels of risk associated with PPE: (i) overall lack/shortages; (ii) insufficiency of fit; and (iii) different policies in terms of risk assessment regarding its use. We hereby explore these three factors through the concepts of embodied absence, embodied insufficiency and embodied emotions as responses to risk and PPE policies.

3.1. Embodied absence — Lack and shortage

Firstly, lack and shortages. Throughout the COVID‐19 pandemic, though particularly in the early weeks in March and April, there was a consistent, and de facto lack, of PPE available globally, though this was particularly pronounced in the UK (Foster & Neville, 2020), with Louise stating:

at the start it was basically face and, paper face masks, plastic apron and some gloves, you know normal gloves that are on the ward, and that’s what we were told to wear if we were within two metres of a confirmed or a highly suspected symptomatic case … pragmatically there wasn’t enough, and when you’re faced with limited resources you need to distribute them and you know set protocols for their use appropriately for looking at need.

Whilst not all healthcare professionals engage in close contact and/or aerosol generating procedures 2 (AGPs), the risk of contracting COVID‐19 on the front line is elevated compared to that of the general public, particularly for those from a BAME background: those of Filipino birth and those who are older have been disproportionately affected by COVID‐19, with specific underlying conditions increasing risk of severe illness. In addition, being male has also been associated with severe disease (BMA, 2020) further exacerbated by PPE shortages. There was little to no choice for Louise to say ‘no’ to enforced ways of working, a way of working which ultimately put lives at risk. The embodiment of risk is presented here not only as deeply personalized, but also as a defining characteristic of the COVID‐19 pandemic in the UK context under a Conservative government which notably appears to have tailored its guidance to the availability of PPE (Foster & Neville, 2020), rather than guidelines driving stock availability. Louise reflects as follows:

in an ideal world of course we would have had better PPE, we would have all have had the higher FFP3 masks, we would have all been using the glasses and goggles from the start, we would have all had gowns, but we weren’t because we didn’t have it because there was lack of stock, lack of distribution, lack of forward‐planning … I varied between feeling not protected enough, to having a feeling of acceptance that as medical staff we were all just going to get it anyway, because ultimately we didn’t feel that the PPE we had, would protect us.

Louise also discussed how the rhetoric of scarcity shaped the embodiment of risk in practice, though there was a critical gap of around three weeks between the upsurge of the pandemic in March 2020 and April 2020, critically, this is also the period where the daily death rates from COVID‐19 were the highest (NHS England, 2020b). Louise highlights her lived experience of PPE scarcity:

there was quite a lot of chat of this is very precious, we need to be careful with our resource, to minimise our use, but they, they always claimed once we started using it, once they changed the policy to that we would use it, about three weeks after the government guidelines, that we had enough.

This shifts the burden of responsibility onto the individual health workers, to take care not to let their bodies overuse the materials, but then claim that there was always enough (perhaps because of the under‐use and under‐protection of these workers).

3.2. Embodied insufficiency — Bodies that do not fit

Secondly, even where there was access, the PPE is designed and manufactured to fit and, in turn, work most effectively, when worn on the male ‘standard’ body (Topping, 2020), this was also a concern expressed by Louise:

you do see colleagues who are very petite and are completely drowned by masks, by, you know you can’t get gloves small enough, can’t get aprons small enough, you can’t get gowns small enough … I mean absolutely it’s going to hinder them in doing some, especially I think it’s going to impact the nursing staff most … a lot of bodged jobs, taping things up, uncomfortable people having wearing heavier things than they needed to, sweating more, when staff in high intensity areas, such as ITU, were wearing kit for 12, are on 12 hour shifts and things don’t fit and things are restrictive, loose, getting caught on pieces of equipment.

In this respect, bodies other than the ‘standard’ body ‘are judged and identified as problematic for organizations’ (Simpson & Lewis, 2005, p. 1264). In some organizational contexts, women’s bodies are perceived as threatening, for example, in the military (Steidl & Brookshire, 2018) and corporate leadership (Mavin & Grandy, 2018), but in these healthcare contexts, the threat is borne by the women themselves, it is their bodies that are threatened by insufficient access to and suitability of the protective equipment that could help reduce the risk.

I find it hard to watch the statistics of looking at you know every time they announced another GP had died, another hospital consultant had died, you know and nurses, I find it difficult to watch that but when you look at you know, when you think about proportion and you know who’s going to get what, but then to find out that that you know the hugely high percentage of doctors who lost their lives who are part the BAME group …, I mean once that kind of trend was being more and more identified there were more safeguards put in place, the risk assessments, we’re not treating all colleagues the same, we’re not putting in more protective measures for people in that group, but u that didn’t happen for a while and so, yeah that was just hard to watch.

There are also strong linkages here not only between the lack of fit in the physical sense, but also in the attitudinal sense, related to silencing and the facets of control and compliance in inequality regimes (Acker, 2006). We argue that the silencing of doctors and other healthcare professionals over PPE shortages, which has been endemic (Doctors’ Association UK [DAUK], 2020), serves as a direct expression of control and compliance over individuals (Acker, 2006), characterized by the ‘systematic differences in access to and control over resources for provisioning and survival’ (p. 444). This silencing and [lack of] access to sufficient PPE, in turn, serves to deepen gendered and racialized experiences of caregiving, and indeed, the embodiment of risk in practice, during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Louise reflects as follows:

Within the chain of hierarchy, line managers etc., going up, and got conflicting answers, which I find difficult, and no change, I sought guidance from the Royal College of GPs, I sought guidance from the British Medical Association, from a local trust occupational health, who all kept pointing back to the Public Health England guidelines saying this is what they should be following, I don’t understand why they’re not …, I discussed and raised my concerns and got conflicting answers, and what I felt at the time was unsupportive and, advice, and that they didn’t acknowledge my concerns.

It is now known that: ‘Multiple doctors have approached DAUK having been discouraged from speaking up. In some cases doctors have been bullied into silence, disciplined, or told their careers are under threat’ (DAUK, 2020). In this respect, there is an embodiment of risk in speaking out (Simpson & Lewis, 2005) characterized by the fears of being associated with the reporting of PPE shortages, which are gradually coming to the fore, despite, for example, the recent PPE survey by DAUK finding that 47 per cent of respondents were told explicitly not to mention PPE shortages on social media (DAUK, 2020).

3.3. Embodied emotion — Responses to risk policies

Throughout the interview it was evident that Louise was in emotional flux in relation to her experiences of risk, mobilizing formal risk assessment, the following of PPE guidelines (from Public Health England), experiencing tensions between the source of her emotion and how to mitigate this in order to carry out her job on the front line. In healthcare contexts, the risks of contracting COVID‐19 are for many, greater than those risks in everyday life, and there has been sustained media coverage not only of the deaths of professionals in the NHS, but also the risks to which they are exposed. Notably ‘both caring for the sickest patients with Covid‐19 and undertaking airway management (so‐called aerosol generating procedures, AGP) are associated with high risk of viral exposure and transmission’ (Kursomovic, Lennane, & Cook, 2020).

She reflects on her emotions as follows:

a mixture of between acceptance and, and being pragmatic about that, to also feeling frustrated and I get at times some fear and just frustration and as, and that escalated as we saw more and more cases of doctors, nurses, health professionals contracting it, be it my colleagues and of people dying, of healthcare professionals dying.

There is an extent to which the assessment of risk, and different approaches thereto mentioned above, have been a source of both negative and positive emotion for Louise. In this respect, the different interpretations of risk assessment have caused worry and concern in some contexts, and have provided a source of comfort in others. In the first example below, on raising the issue of lack of the appropriate PPE, she encountered much conflicting information and indeed also emotional conflict, as the following quote highlights:

I then worked in a department where we had a very different PPE policy and that policy did not sit well with me, erm it did not appear to me to be following the PHE guidelines … I thought it was potentially putting patients at risk, and ultimately it wasn’t following the guidelines, so it made me angry, it made me fearful, it made me frustrated, it made me feel very stressed and confused as I, what I should be doing … I’m very clear in guidelines and doing the right thing, and so therefore, there was an ethical moral dilemma and conflict that I wasn’t you know, within the department I was working with on PPE, which as I say luckily eventually got resolved. But otherwise it was, I guess with some of my, I find it, I find it hard to watch the statistics of looking at you know every time they announced another GP had died, another hospital consultant had died, you know and nurses; I find it difficult to watch.

Even where PPE is available and fits, there were different policies regarding its use and whilst to a certain extent variation according to context could be expected, as well as changes in relation to new learning and information about the nature of the virus and its transmission, variations in interpretation do affect the nature of the risk and its experience. But for Louise, the variation in interpretation in this context has been a source of discomfort and distress in her lived experiences.

The embodiment of risk through emotion is deeply personalized, gendered, racialized and felt acutely by front‐line NHS healthcare professionals, typified by the constant emotional and pragmatic tensions of caregiving, self‐protection, service and the balancing of risk in an extreme circumstance. So in some circumstances such as those above, assessing risk has been a source of tension. In other contexts, however, there is an extent to which the assessment of risk has actually helped Louise to mitigate her emotional responses as a coping mechanism and source of comfort:

I, you know, was able to balance that out with looking at risk factors of, personal health risk factors of me, not coping with it well and not surviving it, and I was pretty confident that if I caught it I would, although it would not be very nice, I would get through it. So I didn’t have, like a paralysing fear or anything about it. Yeah I accepted it was part of my job, I mean again I looked at everything as a medical professional from a risk factor point of view.

In this case, Louise has absorbed a trust in the processes of risk such that she could ‘balance that out’, she could cope with the level of risk because of the way that level of risk was presented. We argue here that because of the UK government’s approach to risk, and drawing on the recent work of Sibony (2020) that risk‐taking by the government, as aforementioned, contributed to not only PPE shortages but in turn, also the embodiment of risk in practice. Furthermore, whilst deliberating prospect theory (Tversky & Kahneman, 1992), whereby if we consider the [rightfully] negative framing of the pandemic and associated deaths, this has arguably led to more risk‐taking, particularly where behavioural science and behavioural nudges appear to be central to government policy making (Sibony, 2020). We have witnessed a deeply disturbing trickle‐down effect of the government’s approach to risk, contributing further to the [gendered and racialized] inequalities of risk, with diminishing sensitivity and assumed responsibility on the part of the state.

4. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK OF THE EMBODIMENT OF RISK DURING COVID‐19

The following conceptual framework captures the multi‐level facets of the embodiment of risk which we have explored in this article, through lived and expressed experiences of risk, and observations of the inequality of risk in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic documented in the recent extant, evolving literature, as well as Acker’s (2006) inequality regimes framework as a sensitizing framework.

The conceptualization of the embodiment of risk during COVID‐19 serves to cast light on the role of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the embodiment of risk, the multifaceted nature of emotions of risk and the associated inequality of risk, which are framed as contemporary expressions of inequality regimes (Acker, 2006). The inequality of risk, and its connection to the shortages in PPE, may be directly linked to Acker’s (2006) defining of inequality as systemic disparities between individuals’ ‘access to and control over resources and outcomes’ (p. 443), the organizing of work and ‘control over resources for provisioning and survival’ (p. 444).

We assert that the embodiment of risk is personified in the crisis by the lack of PPE, in turn shaping emotions of risk and lived experience of the tensions between self‐protection and exposure to the COVID‐19 virus, within the parameters of policy and guidance. Vulnerability to contracting COVID‐19 through work on the front line, as was the case for Louise, brings together the embodiment of risk, the emotion of risk and by definition also the inequality of risk experienced by front‐line workers, who have no option but to be exposed to the operational and occupational risks of their work.

This conceptualization of risk, and the typologies we propose, in the COVID‐19 pandemic assists us in the interpretation of the linkages between paternalistic, discursive policy making at the macro level and the effects on the [multiple] levels of risk experienced by front‐line medical workers such as doctors like Louise, at the individual level.

4.1. Reflections — The inequalities of risk

This article has explored Louise’s lived experiences as an NHS doctor, casting light upon the embodied amplification of inequalities, paternalistic discourses around risk, equipment shortages and lived experience of exposure to risk, and we draw linkages between PPE inadequacies and vertical gender segregation in the NHS, as expressions of inequality regimes in the context of COVID‐19, thereby conceptualizing risk in the context of a contemporary inequality regime. Even organizations such as the NHS which have ‘explicit egalitarian goals, develop inequality regimes over time’ (Acker, 2006, p. 443); the ultimate expression of this is the disproportionate number of BAME healthcare professionals dying (NHS England, 2020a), albeit we remain hopeful that the visibility of inequality is increasing and, in turn, decreasing its legitimacy, ultimately to positively contribute to the protection of those who are most acutely affected by the entrenched and systemic inequalities, and indeed COVID‐19.

It is clear that there are many gendered elements of the COVID‐19 pandemic emerging, and over time we anticipate that this will, unfortunately, contribute to the deepening of gender inequality, vertical gender segregation, and women’s lived experiences of work and organizing, albeit the potential for the pandemic to counter macho masculinity in organizations (Alcadipani, 2020) remains to be seen. It is also important to reflect upon the aforementioned paternalistic, discursive policy making of the UK government in the [at the time of writing] COVID‐19 pandemic and indeed critically deliberate why ‘did “behavioural fatigue” have the honour of featuring as policy justification?’ (Sibony, 2020, p. 356), thus arguably increasing the inequality of risk.

Ultimately, there is an extremely worrying disconnect between the state, policymakers, policy enactment and lived experiences of work on the front line of work during COVID‐19; this is of course indeed not novel, but in the current VUCA 3 context, it is costing lives, further entrenching existing gender and race inequalities, thereby setting a stage for long‐term regression of equality. We argue here that PPE inadequacies notionally serve as embodied amplification of inequalities, and in turn, also a crisis for feminism, with 80 per cent of the NHS workforce being women (albeit vertical gender segregation is also a core organizational characteristic). The intertwining of the embodiment of inequality, the crisis for feminism and the long‐term implications of COVID‐19 on women are not only complex and axiomatic, but also must serve as an opportunity for positive change in the healthcare provision and, in turn, working conditions, thereby potentially contributing positively to inclusion and positive changes in lived experiences of work and the embodiment of risk.

DATA ACCESSIBILITY STATEMENT

The data for this research will not be made publicly available in a repository, in order to project the identity of the participant further.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are immensely grateful to our participant for taking part in this research, and sharing her experiences of front‐line work during the pandemic and speaking so candidly. In our writing, we would also like to thank all NHS staff and key workers, for their unwavering commitment and dedication, emotional labour and service — Thank You.

Biographies

Emily Yarrow is a Lecturer in International Human Resource Management at Portsmouth Business School. Emily's research focuses on the impact of research evaluation on female academics′ careers; gendered networks; and inequality regimes. Her work contributes to understandings of gendered organizational behaviour and women's lived experiences of organizational life.

Victoria Pagan is a lecturer in strategic management at Newcastle University Business School. Her research interests include epistemic justice and her work in progress includes an exploration of the uses, and impacts of the uses, of non‐disclosure agreements in a range of workplace context.

Yarrow E, Pagan V. Reflections on front‐line medical work during COVID‐19 and the embodiment of risk. Gender Work Organ. 2021;28(S1):537–548. 10.1111/gwao.12505

ENDNOTES

Devolved decision‐making in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales has been, and is, in place with different lockdown easing dates, through centralized policy making is still a significant and indeed contested factor, particularly where the notion of herd immunity, behavioural nudges and behavioural science which characterize the UK government’s policy approach to COVID‐19, are concerned (Institute for Government, 2020).

‘The highest risk of transmission of respiratory viruses is during AGPs of the respiratory tract, and use of enhanced respiratory protective equipment is indicated for health and social care workers performing or assisting in such procedures’ (Public Health England, 2020).

Volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous context.

REFERENCES

- Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender & Society, 4, 139–158. 10.1177/089124390004002002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Acker, J. (2006). Inequality regimes: Gender, class, and race in organizations. Gender & Society, 20(4), 441–464. 10.1177/0891243206289499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alcadipani, R. (2020). Pandemic and macho organizations: Wakeup call or business as usual? Gender, Work and Organization. Advance online publication. 10.1111/gwao.1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, D. (2019). Men are doctors and women are nurses, right? Of course not, but is this what primary school kids really think? Retrieved from https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Men%20are%20doctors%20and%20women%20are%20nurses%20blog_0.pdf

- Alvesson, M. , & Sköldberg, K. (2000). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research. London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Beaussier, A. L. , Demeritt, D. , Griffiths, A. , & Rothstein, H. (2016). Accounting for failure: Risk‐based regulation and the problems of ensuring healthcare quality in the NHS. Health, Risk & Society, 18(3–4), 205–224. 10.1080/13698575.2016.1192585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BMA . (2020). Covid‐19: Risk assessment. Retrieved from https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/Covid-19/your-health/Covid-19-risk-assessment

- Bruni, A. , Gherardi, S. , & Poggio, B. (2004). Doing gender, doing entrepreneurship: An ethnographic account of intertwined practices. Gender, Work and Organization, 11, 406–429. 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2004.00240.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, R. , & Le Feuvre, N. (2003). Continuity and change in the gender segregation of the medical profession in Britain and France. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 23(4–5), 36–58. 10.1108/01443330310790507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cure, L. , Zayas‐Castro, J. , & Fabri, P. (2014). Challenges and opportunities in the analysis of risk in healthcare. IIE Transactions on Healthcare Systems Engineering, 4(2), 88–104. 10.1080/19488300.2014.911786 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doctors’ Association UK (DAUK) . (2020). Protect the frontline. Retrieved from https://www.dauk.org/protectthefrontline

- Foster, P. , & Neville, S. (2020, May 1). How poor planning left the UK without enough PPE. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/9680c20f-7b71-4f65-9bec-0e9554a8e0a7

- Hearn, J. (2000). On the complexity of feminist intervention in organizations. Organization, 7, 609–624. 10.1177/135050840074006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekam, S. , & Shymko, Y. (2020). Coping with the COVID‐19 crisis: Force majeure and gender performativity. Gender, Work and Organization. Advance online publication. 10.1111/gwao.12479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupkau, C. , & Petrongolo, B. (2020). Work, care and gender during the Covid‐19 crisis. Retrieved from http://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/cepCovid-19-002.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Institute for Government . (2020). Coronavirus and devolution. Retrieved from https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/coronavirus-and-devolution

- Kerfoot, D. , & Knights, D. (1993). Management, masculinity and manipulation: From paternalism to corporate strategy in financial services in Britain. Journal of Management Studies, 30(4), 659–677. 10.1111/j.1467-6486.1993.tb00320.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kursumovic, E. , Lennane, S. , & Cook, T. M. (2020). Deaths in healthcare workers due to COVID‐19: the need for robust data and analysis. Anaesthesia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T. H. , Johnstone, J. , & Loeb, M. (2011). Vaccine herd effect. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 43(9), 683–689. 10.3109/00365548.2011.582247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. (2017). The masculinisation of ethical leadership dis/embodiment. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(2), 263–278. 10.1007/s10551-015-2831-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manne, K. (2019). Down girl: The logic of misogyny. London, UK: Penguin Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Mavin, S. , & Grandy, G. (2018). Women leaders, self‐body‐care and corporate moderate feminism: An (im)perfect place for feminism. Gender, Work and Organization, 26(11), 1546–1561. 10.1111/gwao.12292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar, S. (2020). Feminism and gendered impact of COVID‐19: Perspective of a counselling psychologist. Gender, Work and Organization. Advance online publication. 10.1111/gwao.12482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS Employers . (2016). The NHS workforce infographic. Retrieved from https://www.nhsemployers.org/-/media/Employers/Publications/NHS-Workforce-Infographic-120517-FINAL.pdf

- NHS England . (2020a). Coronavirus: Addressing the impact of COVID‐19 on BAME staff in the NHS. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/workforce/addressing-impact-of-Covid-19-on-bame-staff-in-the-nhs/

- NHS England . (2020b). COVID‐19 total announced deaths 17 June 2020 — Weekly tables. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/Covid-19-daily-deaths/

- Politico . (2020). Going viral: Boris Johnson grapples to control the coronavirus message. Retrieved from https://www.politico.eu/article/going-viral-british-prime-minister-boris-johnson-grapples-to-control-coronavirus-Covid19-message/

- Public Health England . (2020). Guidance COVID‐19 personal protective equipment (PPE). Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/covid-19-personal-protective-equipment-ppe#ppe-guidance-by-healthcare-context

- Riska, E. (2010). Women in the medical profession: International trends. In The Palgrave handbook of gender and healthcare (pp. 389–404). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sibony, A. L. (2020). The UK COVID‐19 response: A behavioural irony? European Journal of Risk Regulation, 11(2), 350–357. 10.1017/err.2020.22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, R. , & Lewis, P. (2005). An investigation of silence and a scrutiny of transparency: Re‐examining gender in organization literature through the concepts of voice and visibility. Human Relations, 58(10), 1253–1275. 10.1177/0018726705058940 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steidl, C. R. , & Brookshire, A. R. (2018). Just one of the guys until shower time: How symbolic embodiment threatens women’s inclusion in the US military. Gender, Work and Organization, 26(9), 1271–1288. 10.1111/gwao.12320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Topping, A. (2020). Sexism on the Covid‐19 frontline: ‘PPE is made for a 6ft 3in rugby player’. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/24/sexism-on-the-covid-19-frontline-ppe-is-made-for-a-6ft-3in-rugby-player

- Tversky, A. , & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), 297–323. 10.1007/BF00122574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P. (2020). No 10 denies claim Dominic Cummings argued to ‘let old people die’. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/mar/22/no-10-denies-claim-dominic-cummings-argued-to-let-old-people-die

- Weaver, M. (2020). Pressure on Dominic Cummings to quit over lockdown breach. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/may/22/dominic-cummings-durham-trip-coronavirus-lockdown

- West, C. , & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1(2), 125–151. 10.1177/0891243287001002002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C. L. , Muller, C. , & Kilanski, K. (2012). Gendered organizations in the new economy. Gender & Society, 26, 549–573. 10.1177/0891243212445466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this research will not be made publicly available in a repository, in order to project the identity of the participant further.