Abstract

BACKGROUND

COVID‐19 has infected millions of people worldwide, particularly in older adults. The first cases of possible reinfection by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) were reported in April 2020 among older adults.

DESIGN/SETTING

In this brief report, we present three geriatric cases with two episodes of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection separated by a symptom‐free interval.

PARTICIPANTS

The participants of this brief report are three cases of hospitalized geriatric women.

MEASUREMENTS/RESULTS

We note clinical and biological worsening during the second episode of COVID‐19 for all three patients. Also, there is a radiological aggravation. The second episode of COVID‐19 was fatal in all three cases.

CONCLUSION

This series of three geriatric cases with COVID‐19 diagnosed two times apart for several weeks questions the possibility of reinfection with SARS‐CoV‐2. It raises questions in clinical practice about the value of testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection again in the event of symptomatic reoccurrence. J Am Geriatr Soc 68:2179–2183, 2020.

Keywords: COVID‐19, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, recurrence

Since December 2019, the COVID‐19 pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), has infected more than 6 millions people worldwide 1 and is responsible for a large number of deaths, particularly among older adults. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Isolation and containment are the main measures to break chain contamination in primary prevention in this population 6 ; the tertiary prevention is based on the assumption of effective immunization of infected individuals to prevent recurrence of the infection. 5 However, the first cases of possible reinfection by SARS‐CoV‐2 were reported in April 2020 among adults. 7 Here, we report a recurrence of the SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in a series of older patients in Saint‐Etienne, France.

The clinical and laboratory data of cases are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics

| Characteristics | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics | |||

| Age, y | 84 | 90 | 84 |

| Sex | F | F | F |

| Comorbidities | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Diabetes mellitus, type II | ☑ | ||

| Arterial hypertension | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Heart disease | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Cancer | ☑ | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ☑ | ||

| Immunosuppression | ☑ | ||

| COVID‐19 (first time) | |||

| Diagnosis of COVID‐19 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR test | Yes/Mar 26 | Yes/Apr 5 | No/Apr 15 |

| Chest CT scan | Yes/Mar 24 | No/Apr 5 | Yes/Apr 16 |

| Biological markers | |||

| Neutrophil count, ×109 cells/L | 2.77 | 8.23 | 6.17 |

| Lymphocyte count, ×109 cells/L | 0.77 | 2.16 | 0.13 |

| C‐reactive protein, mg/L | 88 | 47 | 160 |

| Treatments received | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Antiviral therapy | |||

| Antibiotics | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Corticosteroids | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Death | No | No | No |

| Biological markers before the second COVID‐19 | |||

| Neutrophil count, ×109 cells/L | 5.98 | 7.29 | 10.41 |

| Lymphocyte count, × 109 cells/L | 1.27 | 1.67 | 0.73 |

| C‐reactive protein, mg/L | 8.7 | 55 | 31.5 |

| COVID‐19 (second time) | |||

| Diagnosis of COVID‐19 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR test | Yes/May 6 | Yes/May 6 | Yes/May 7 |

| Chest CT scan | Yes/May 4 | Yes/May 14 | Yes/May 7 |

| Biological markers | |||

| Neutrophil count, ×109 cells/L | 11.96 | 11.64 | 10.93 |

| Lymphocyte count, × 109 cells/L | 0.47 | 0.89 | 0.23 |

| C‐reactive protein, mg/L | 304.5 | 181 | 146.9 |

| IL‐6, ng/L | 235 | 201 | |

| Treatments received | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Antiviral therapy | |||

| Antibiotics | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Corticosteroids | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Immunotherapy | ☑ | ‐ | ☑ |

| Death | Yes/May 17 | Yes/May 19 | Yes/May 23 |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; F, female; IL‐6, interleukin 6; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

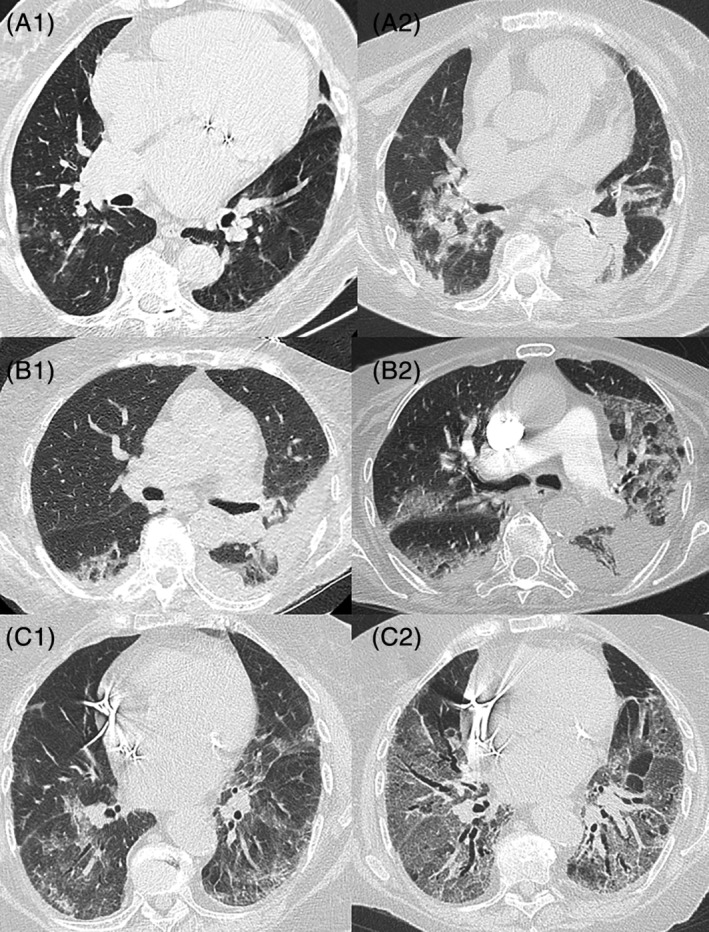

Patient 1 was an 84‐year‐old woman with medical history of high blood pressure, beta‐lactam allergy, heart failure, atrial fibrillation treated by rivaroxaban, diabetes mellitus, type II, treated with insulin, chronic renal failure, and chronic respiratory failure under long‐term oxygen (1 L/15 h a day). The patient exhibited specific symptoms of COVID‐19, with cough, fever, and respiratory signs with oxygen desaturation at 79%. The COVID‐19 diagnosis was made on the typical computed tomographic (CT) scan appearance on March 24, 2020, with bilateral ground glass lesions predominating on the right lung (Figure 1‐A1), confirmed by a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) performed on nasopharyngeal sample on March 26 (cycle threshold (Ct) of 31.4). She was hospitalized in an acute‐care unit dedicated to COVID‐19 on the same day. The patient received levofloxacin for 7 days and a short course of corticosteroids by methylprednisolone, which resulted in clinical and biological improvements, allowing the patient to be referred to a COVID‐19 rehabilitation care unit on April 7. During her stay in this unit, C‐reactive protein (CRP) and lymphocyte rate were normalized. On May 4, more than 1 month after the first episode, the patient presented with hyperthermia and respiratory signs. She was readmitted into an acute‐care unit dedicated to COVID‐19, and SARS‐CoV‐2 RT‐PCR tests were performed on May 8, in nasopharyngeal swab and sputum, and were positive (Ct of 17.5 and 18.1, respectively). Viral cultures of sputum and nasopharyngeal secretions performed on Vero cells showed cytopathic effect in plaque assay. Virological sequencing has been performed and belongs to the B1 (European) lineage, according to the Pangolin classification. 8 Chest CT scan was compatible with COVID‐19 acute infection and revealed bilateral moderate lung lesions (10%–25%), which were greater than previously (Figure 1‐A2). The biological inflammatory syndrome was marked, with CRP at 304.5 mg/L and a deep lymphopenia at 0.47 Giga/L and interleukin (IL)‐6 = 235 ng/L. Neutralizing antibodies to SARS‐CoV‐2 were negative on May 8 and faintly positive (rate of 1:10) on May 15. The patient was treated symptomatically with oxygen therapy and noninvasive ventilation due to respiratory acidosis from May 12. She received levofloxacin from May 5 and aztreonam from May 8, although no superinfection was documented. Methylprednisolone, 60 mg/d, was added on May 10. Immunotherapy by tocilizumab (8 mg/kg) was administered on May 12. The patient finally died on May 17 due to respiratory and heart failure despite high‐dose furosemide.

Figure 1.

Chest computed tomography scans.

Patient 2 was a 90‐year‐old dependent woman living in a nursing home and exhibiting diabetes mellitus, type II, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and major neurodegenerative pathology (Alzheimer's disease). Diagnosis of COVID‐19 was suspected in early April 2020 based on a clinical picture of cardiorespiratory decompensation with atrial fibrillation with fever and was confirmed on April 5 with SARS‐CoV‐2 RT‐PCR positive test on a nasopharyngeal specimen (Ct of 21). She was hospitalized in a COVID‐19 acute‐care unit. The chest CT scan revealed signs of pleural effusions bilaterally, with no sign typical of pulmonary SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (Figure 1‐B1). The patient received various treatments with preventive anticoagulation (the risk‐benefit ratio was not in favor of curative anticoagulation), diuretics, and antibiotics by ofloxacin and 5 days of prednisolone, 40 mg/d. Clinical improvement was noted, and the patient was transferred to a COVID‐19 rehabilitation care unit on April 21, before she was able to return to her nursing home on May 7. The patient kept an inflammatory syndrome with a CRP stable at 55 in the context of chronic pressures sores. Her second hospitalization, in a COVID‐19 acute‐care unit, on May 11, was motivated by the onset of major dehydration with hypernatremia measured at 166 mmol/L, oxygen saturation at 93% under 4 L of oxygen, melena, and marked deterioration of her general condition. Biology reported a marked lymphopenia at 0.18 Giga/L and CRP at 181 mg/L. The SARS‐CoV‐2 RT‐PCR test was positive on a nasopharyngeal swab (Ct at 18.8) on May 6. On May 14, following respiratory degradation, a chest CT scan showed pulmonary condensation and bilateral diffuse crazy paving affecting approximately 25% to 50% of the lung parenchyma, with bilateral proximal lobar pulmonary embolism (Figure 1‐B2). No serological test was performed. Palliative care was decided after discussion with the family and multidisciplinary validation. The patient finally died on May 19.

Patient 3 was an 84‐year‐old woman with medical history of rhythmic heart disease treated with a pacemaker, pulmonary embolism treated with rivaroxaban, arterial hypertension, and rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate, 15 mg/wk, and corticosteroids (prednisone, 13 mg/d). She exhibited symptoms of COVID‐19, combining fever, asthenia, ageusia, and respiratory signs with dry cough, polypnea (breathing rate = 32/min), oxygen desaturation with 93% under 3 L of oxygen. She was hospitalized in an acute‐care unit dedicated to COVID‐19 on April 16, 2020, with a positive diagnosis of COVID‐19 based on a typical chest CT scan showing lung lesions, such as crazy paving and ground glass opacity greater than 50% bilaterally (Figure 1‐C1). The SARS‐CoV‐2 RT‐PCR test performed on nasopharyngeal sample was negative twice. These were probably false negatives due to inadequate sampling. Patient has typical COVID‐19 symptoms, and no other infectious cause was found. Sputum could not be collected. The CRP was measured at 160 mg/L and lymphocytes at 0.13 Giga/L. The patient received ceftriaxone for 7 days, rovamycine for 5 days, and discontinuation of methotrexate treatment replaced by an increase in corticosteroids (prednisone = 60 mg/d) and oxygen therapy until 4 L. There was a clinical‐biological improvement, with oxygen withdrawal and normalization of the inflammatory syndrome that allowed the patient to be referred to a rehabilitation care unit dedicated to COVID‐19 on April 27 under prednisone, 30 mg/d. Sudden respiratory deterioration occurred on May 6, with 80% desaturation requiring oxygen therapy, dry cough, and fever. Nasopharyngeal samples for SARS‐Cov‐2 RT‐PCR test were found positive (Ct at 16.9 and 14.7 on May 8 and 11, respectively). Viral culture was performed on Vero cells and found positive. Virological sequencing has been performed and belongs to the B1 (European) lineage, according to the Pangolin classification. 8 CT scan revealed a severe bilateral pneumonia (Figure 1‐C2). At readmission, biology reported marked lymphopenia at 0.23 Giga/L, CRP at 146 mg/L, and IL‐6 at 201 ng/L. A rise of neutralizing antibodies against SARS‐CoV‐2 was observed from May 8 to May 15 (titers from <10 to 40). She received ceftriaxone and methylprednisolone, 60 mg/d, from May 8 and high‐flow oxygen. Cotrimoxazole was adjuncted on May 19 to exclude plausible pneumocystosis superinfection. After validation in a multidisciplinary meeting, the patient received convalescent COVID‐19 plasma transfusion on May 16. However, the respiratory status deteriorated, with major desaturation despite 20 L of oxygen and she finally died on May 23.

DISCUSSION

We reported here three geriatric cases with two episodes of COVID‐19 separated by a symptom‐free interval of weeks.

This sequential picture may be explained by either the persistence of nonviable RNA of SARS‐CoV‐2 after the first COVID‐19 episode, by SARS‐CoV‐2 reinfection, or by COVID‐19 relapse. 9 In fact, viral replication was found during the second episode in all three cases, which makes the first hypothesis unlikely. The second wave of respiratory disease could have been caused by something other than SARS‐CoV‐2, but all virological and bacteriological infectious samples were negative, except for COVID‐19. Also, the three women were placed in isolation rooms in hospital units dedicated to COVID‐19, with caregivers trained and equipped to comply with the isolation measures. In addition, the symptom‐free interval was relatively short. Thus, the hypothesis of reinfection with a new strain is also unlikely.

A relapse of COVID‐19 seems to be the preferred hypothesis that would yet need comparisons of strains with sequencing to be affirmed. However, the absence of antibodies presented at readmission for two of the three patients, 22 and 41 days after the first episode, is in favor of a possible reactivation. 10 For the two patients with initially negative serology, a common seroconversion to clinical severity should be noted. This immune reaction may be the cause of clinical deterioration. 11 , 12 One hypothesis would be that these episodes are linked to the persistence of the virus in a reservoir (sanctuary site), as previously suggested for other viral infections. 13 Immunosenescence would have a role in the observed clinical pictures, with a possible nonresponse at the time of the first COVID‐19 episode. Seroconversion monitoring appears important in the management of the disease. Differential causative diagnoses were excluded for the second episode corresponding to a pneumonia in all cases. This series of three geriatric cases with COVID‐19 diagnosed two times apart for several weeks questions the possibility of reinfection with SARS‐CoV‐2. This raises questions in clinical practice about the value of testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection again in the event of symptomatic reoccurrence.

The three cases we present here did not received diagnostic tests, supposedly negative, during the transient improvement in clinical signs. 14 Prolonged infections 15 , 16 , 17 and reactivations have already been described previously. 18 , 19 , 20 If the risk of recurrence is confirmed, it will be crucial to analyze the risk factors (comorbidities, undernutrition, lymphopenia, and weak immune reaction with a low or even negative serology) but also their severity. The inclusion of these patients in therapeutic trials is complex. 21 It can be assumed that the cytokine storm could be greater than during the first contamination, leading to more serious and more frequently lethal forms. In the three cases reported here, the second episode was fatal in each patient. In the case of the second wave, special attention should be paid to older patients who were affected by COVID‐19 during the first wave.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Author Contributions

All authors had access to the data and a role in writing the manuscript.

Sponsor's Role

No sources of funding were used to assist in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control [Internet]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19-pandemic. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 2. Sacco G, Brière O, Asfar M, Guérin O, Berrut G, Annweiler C. Symptoms of COVID‐19 among older adults: systematic review of biomedical literature. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil. 2020;18(2):135‐140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Applegate WB, Ouslander JG. COVID‐19 presents high risk to older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(4):681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abrams HR, Loomer L, Gandhi A, Grabowski DC. Characteristics of U.S. nursing homes with COVID‐19 cases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ahn D‐G, Shin H‐J, Kim M‐H, et al. Current status of epidemiology, diagnosis, therapeutics, and vaccines for novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;30(3):313‐324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Celarier T, Lafaie L, Goethals L, et al. Covid‐19: adapting the geriatric organisations to respond to the pandemic. Respir Med Res. 2020;100774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.South Korea reports more recovered coronavirus patients testing positive again. Reuters [Internet]. 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-southkorea-idUSKCN21V0JQ. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 8. Rambaut A, Holmes EC, Hill V, et al. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS‐CoV‐2 to assist genomic epidemiology. bioRxiv. 2020;046086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gombar S, Chang M, Hogan CA, et al. Persistent detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA in patients and healthcare workers with COVID‐19. J Clin Virol. 2020;129:104477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID‐2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465‐469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, et al. Antibody responses to SARS‐CoV‐2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kirkcaldy RD, King BA, Brooks JT. COVID‐19 and postinfection immunity: limited evidence, many remaining questions. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2245‐2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Malvy D, McElroy AK, Clerck H de, Günther S, Griensven J van . Ebola virus disease. The Lancet. 2019;393(10174):936‐948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haut Conseil de Santé Publique [Internet]. SARS coronavirus‐2: clinical criteria for safely ending isolation of infected patients. https://www.hcsp.fr/Explore.cgi/AvisRapports. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- 15. Ye G, Pan Z, Pan Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 reactivation. J Infect. 2020;80(5):e14‐e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ravioli S, Ochsner H, Lindner G. Reactivation of COVID‐19 pneumonia: a report of two cases. J Infect. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lan L, Xu D, Ye G, et al. Positive RT‐PCR test results in patients recovered from COVID‐19. JAMA. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li X‐J, Zhang Z‐W, Zong Z‐Y. A Case of a readmitted patient who recovered from COVID‐19 in Chengdu. China. Crit Care Lond Engl. 2020;24(1):152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yoo SY, Lee Y, Lee GH, Kim DH. Reactivation of SARS‐CoV‐2 after recovery. Pediatr Int. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoang VT, Dao TL, Gautret P. Recurrence of positive SARS‐CoV‐2 in patients recovered from COVID‐19. J Med Virol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goh EF, Tan CN, Pek K, Leong S, Wong WC, Lim WS. Not wasting a crisis: how geriatrics clinical research can remain engaged during COVID‐19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]