Abstract

Objective

The objective was to assess anxiety and burnout levels, home life changes, and measures to relieve stress of U.S. academic emergency medicine (EM) physicians during the COVID‐19 pandemic acceleration phase.

Methods

We sent a cross‐sectional e‐mail survey to all EM physicians at seven academic emergency departments. The survey incorporated items from validated stress scales and assessed perceptions and key elements in the following domains: numbers of suspected COVID‐19 patients, availability of diagnostic testing, levels of home and workplace anxiety, severity of work burnout, identification of stressors, changes in home behaviors, and measures to decrease provider anxiety.

Results

A total of 426 (56.7%) EM physicians responded. On a scale of 1 to 7 (1 = not at all, 4 = somewhat, and 7 = extremely), the median (interquartile range) reported effect of the pandemic on both work and home stress levels was 5 (4–6). Reported levels of emotional exhaustion/burnout increased from a prepandemic median (IQR) of 3 (2–4) to since the pandemic started a median of 4 (3–6), with a difference in medians of 1.8 (95% confidence interval = 1.7 to 1.9). Most physicians (90.8%) reported changing their behavior toward family and friends, especially by decreasing signs of affection (76.8%). The most commonly cited measures cited to alleviate stress/anxiety were increasing personal protective equipment (PPE) availability, offering rapid COVID‐19 testing at physician discretion, providing clearer communication about COVID‐19 protocol changes, and assuring that physicians can take leave for care of family and self.

Conclusions

During the acceleration phase, the COVID‐19 pandemic has induced substantial workplace and home anxiety in academic EM physicians, and their exposure during work has had a major impact on their home lives. Measures cited to decrease stress include enhanced availability of PPE, rapid turnaround testing at provider discretion, and clear communication about COVID‐19 protocol changes.

Background and Importance

Although the effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the public's anxiety levels have been well documented by traditional media, the degree to which the pandemic affects physician stress and personal life has not yet been quantified in the United States. 1 , 2 Investigators reported a heavy psychological toll on health care workers in Wuhan and other regions of China. 3 Anticipating a surge in mental health care needs in U.S. health care workers, others have called for similar systematic assessments of frontline providers. 4 , 5

Goals of This Investigation

In mid‐March 2020, we initiated a longitudinal survey study to assess multiple factors affecting the psychological health of emergency medicine (EM) physicians in the United States during the COVID‐19 pandemic. In our study design, we seek to evaluate different topics that are relevant to three phases of the pandemic: the acceleration phase, the plateau/deceleration phase, and the resolution phase. Herein we report results of the first (acceleration) phase of this study to aid EM physicians and health care systems in their development of programs for stress mitigation in real time. Specifically, we sought to assess home and workplace anxiety, burnout, work‐related stressors, changes to home life, and perceptions as to what measures might ease provider anxiety.

Study Design, Setting, and Selection of Participants

This was a cross‐sectional survey administered via e‐mail from February 23, 2020, to April 10, 2020, to all EM physicians (attending, fellow, and resident) at seven EM residencies and affiliated institutions: University of California San Francisco–UCSF (San Francisco, CA); UCSF–Fresno Medical Education Program (Fresno, CA); Cooper Medical School of Rowan University–CMSRU (Camden, NJ); University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA‐Olive View program with affiliated West Los Angeles VA and Santa Monica UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA); Kern Medical Emergency Medicine Residency (Bakersfield, CA); Louisiana State University Health Science Center (New Orleans, LA); and University of California at San Diego–UCSD (San Diego, CA). Participating sites were primarily recruited through their involvement in the National Emergency X‐radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) network. To broaden the sampling to sites that were experiencing heavy surges of COVID‐19 patients, we contacted investigators at two residencies in New York City (NYC) and one in New Orleans; investigators in NYC believed that their staff were too overloaded to meaningfully participate. We excluded non–clinically active physicians. This study was deemed exempt by the respective institutional review boards.

Methods of Measurement

Collaborating with the University of California Stress Network, we developed a survey instrument to assess perceptions and key elements about the following domains: provider estimates of numbers of patients treated with suspected COVID‐19 infection, availability of COVID‐19 diagnostic testing, home and workplace anxiety, work burnout, identification of work‐related stressors, changes in behavior at home arising from their work during the pandemic, and perceptions as to what measures might decrease provider anxiety. Anticipating the difficulty with response rates to lengthy questionnaires during the acceleration phase of the pandemic, we sought to make our instrument pragmatic and succinct; we adapted selected questions from validated stress and burnout assessment scales that would address our particular domains of study. 6 , 7 For example, to assess emotional exhaustion and burnout, participants were asked to rate on a 1 to 7 scale (1 = not at all, 4 = somewhat, and 7 = very much) “to what extent were you experiencing severe, ongoing job stress where you felt emotionally exhausted, burned out, cynical about your work and fatigued, even when you wake up?” To assess what measures might relieve anxiety related to their work during the pandemic, respondents were presented a list of 11 measures and asked to assign their top five measures (1 = highest priority and 5 = fifth highest priority) that they thought would alleviate some of their anxiety/stress. After pilot testing our preliminary instrument on five physicians to ensure understanding and a completion duration of <10 minutes, our final survey consisted of 32 Likert‐type scale, yes/no, multiple‐choice, and free‐response questions. We sent repeat e‐mail requests to nonresponders twice to increase response rate (Data Supplement S1, Table S1, available as supporting information in the online version of this paper, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acem.14065/full).

Primary Data Analysis

Keeping responses anonymous, we managed survey data using REDCap hosted by the University of California at San Francisco. We used STATA v 15.1 for analyses, summarizing patient characteristics and key responses as raw counts, frequency percent, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQRs). We additionally stratified data and used the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test for medians and difference (Δ) in proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for proportions to compare key question responses for the following subgroups: female versus male, faculty versus resident/fellow, children at home versus no children at home, and surge cities (New Orleans and Camden) versus nonsurge cities (California cities). For the question regarding measures to relieve stress, we created a rank summary of aggregate points. Each respondents' highest priority measure was given 5 points, second given 4 points, and so forth, with the fifth given 1 point; noncited measures were given 0 points.

Results

Characteristics of Participants

We sent the survey to 751 EM physicians and received 426 responses (56.7% response rate; Data Supplement S1, Appendix S1). The response rate among female EM physicians was higher than that from male EM physicians (60.4% vs. 51.9%, difference = 8.5%, 95% CI = 1.4% to 15.5%). Response rates from faculty, fellows, and residents were 57.6, 42.4, and 51.4%, respectively (Table 1, respondent characteristics).

Table 1.

Demographics (n = 426)

| Age (years) | 35 (31–43) |

| Female | 192 (45.1) |

| Physician training level | |

| Faculty | 236 (55.4) |

| Fellow | 19 (4.5) |

| Resident | 168 (39.4) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| African American | 14 (3.3) |

| Asian | 69 (16.2) |

| Asian‐Indian | 3 (0.7) |

| Latinx | 36 (8.5) |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (0.2) |

| Native American | 1 (0.2) |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (0.2) |

| White | 306 (71.8) |

| Home living situation | |

| Alone | 63 (14.8) |

| With roommate(s) | 47 (11) |

| With partner(s) | 308 (72.3) |

| With child < 18 years | 166 (39) |

| With adult > 70 years | 9 (2.1) |

Data are reported as median (IQR) or n (%).

Main Results

Of the 419 (98.4%) respondents who reported patient contact from February 15, 2020, to their survey time, 410 (97.9%) reported seeing patients who they suspected had COVID‐19 infections; the median number of patients they suspected had COVID‐19 was 20 (IQR = 10–30). Respondents estimated that 40% (IQR = 10%–80%) of these suspected cases had received the swab test for COVID‐19; 289 (67.8%) stated that they had a patient test positive and 89 (20.9%) were unsure. On the 1 to 7 scale, the median reported effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on work stress levels was 5 (IQR = 4–6) and on home stress levels was 5 (IQR = 4–6). With regard to emotional exhaustion and burnout, EM physicians reported a before‐the‐pandemic median of 3 (IQR = 2–4) and a since‐the‐pandemic‐started median of 4 (IQR = 3–6; Δ = 0.8, 95% CI = 1.7 to 1.9). We found no significant differences in key question responses comparing faculty versus resident/fellow, children at home versus no children at home, and surge city versus nonsurge city. Female gender respondents reported a higher effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on work anxiety levels (6 vs. 5; median Δ = 1, IQR = 0–2) and on home anxiety levels (6 vs. 5; median Δ = 1, IQR = 0 to 2) than men (Table 2).

Table 2.

Stratification for Key Response Questions

| Characteristics | Effect of Pandemic on Workplace Stress | Effect of Pandemic on Home Stress | Emotional Exhaustion and Burnout | Changed Behavior With Friends and Family Because of Possible Excess Work Exposure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prepandemic | Postpandemic | |||||

| Female (n = 192) | 6 (5,6) | 6 (5,7) | 3 (2,4) | 4 (3,6) | Yes | 174 (90.6) |

| No | 13 (7.8) | |||||

| Unsure | 3 (1.6) | |||||

| Male (n = 229) | 5 (4,6) | 5 (4,6) | 2 (2,4) | 4 (3,6) | Yes | 209 (91.3) |

| No | 17 (74.2) | |||||

| Unsure | 2 (0.9) | |||||

| Faculty (n = 236) | 5 (4,6) | 5 (4,6) | 3 (2,4) | 5 (3,6) | Yes | 210 (89) |

| No | 21 (8.9) | |||||

| Unsure | 3 (1.3) | |||||

| Resident or fellow (n = 187) | 5 (4,6) | 5 (4,6) | 3 (2,4) | 4 (3,6) | Yes | 175 (93.6) |

| No | 9 (4.8) | |||||

| Unsure | 2 (1.1) | |||||

| Have children < 18 in home (n = 166) | 5 (4,6) | 5 (4,6) | 3 (2,4) | 4 (3,6) | Yes | 149 (89.8) |

| No | 13 (7.8) | |||||

| Unsure | 2 (1.2) | |||||

| No children in home (n = 259) | 5 (4,6) | 5 (4,6) | 3 (2,4) | 4 (3,6) | Yes | 238 (91.9) |

| No | 18 (6.9) | |||||

| Unsure | 3 (1.2) | |||||

| California sites (n = 306) | 5 (4,6) | 5 (4,6) | 3 (2,4) | 4 (3,6) | Yes | 279 (91.2) |

| No | 7 (2.3) | |||||

| Unsure | 1 (0.3) | |||||

| Non‐California sites (n = 120) | 5 (4,6) | 5 (4,6) | 3 (2,4) | 4 (3,6) | Yes | 109 (90.8) |

| No | 7 (5.8) | |||||

| Unsure | 1 (0.8) | |||||

Data are reported as median (IQR) or n (%).

IQR = interquartile range.

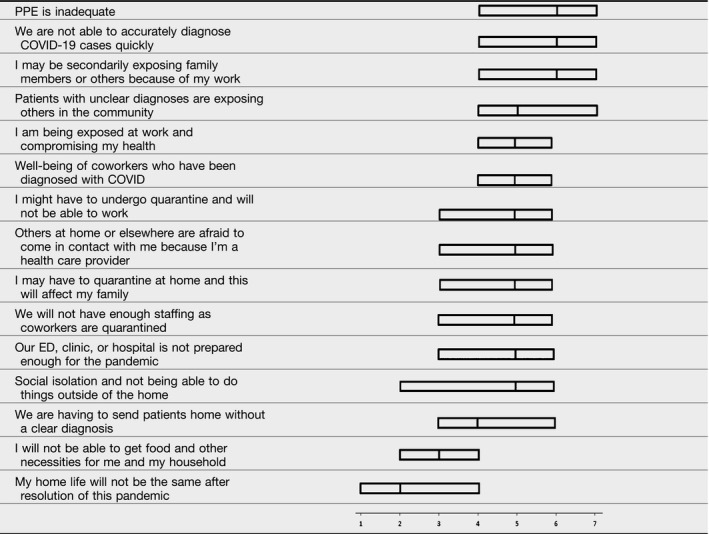

We asked EM physicians' concerns regarding their work as health care providers during the pandemic. The primary concerns were worries about the adequacy of personal protective equipment (PPE), worries about the ability to accurately diagnose COVID‐19 cases quickly, worries about the well‐being of coworkers who have been diagnosed with COVID‐19, and worries that patients with unclear diagnoses are exposing others in the community (Table 3).

Table 3.

Physicians' Concerns Relating to Their Work During the COVID‐19 Pandemic

Median and IQRs to questions “I worry about or that …” on 1 to 7 scale, in which 1 = “not at all,” 4 = “somewhat,” and 7 = “extremely.”

PPE = personal protective equipment.

Median and IQRs to questions “I worry about or that …” on 1 to 7 scale, in which 1 = “not at all,” 4 = “somewhat,” and 7 = “extremely.”

PPE = personal protective equipment.

Most EM physicians (81.7%) had discussed the risks of their excess exposure as health care workers during the pandemic with family and friends and most (90.8%) had changed their behavior with them as a result of this possible excess exposure, with decreased signs of affection (decreased hugging and kissing) being the most commonly cited change (76.8%). Respondents were somewhat concerned when asked how much they believed that friends and family were treating them differently as a result of their work‐related potential exposure to COVID‐19, with a median level of concern of 4 (IQR = 2–5). The most common reported changes by friends and family were expressions of concern about the EM physician participants' health (65.3%), expressions of concern about their exposure to COVID‐19 because of contact with the EM physician (42.3%), and a reluctance of family members to be in close contact with the EM physician (40.4%).

In Table 4, we present a ranked summary of responses of measures that would alleviate provider stress. The highest ranked measures to alleviate anxiety/stress related to the COVID‐19 pandemic were enhanced availability of PPE, rapid COVID‐19 testing with physician discretion, clear communication about changes in COVID‐19 protocols, and assurance that physicians can take leave for care of family and self.

Table 4.

Rank Summary of Measures That Emergency Physicians Believe Would Relieve Their Stress Related to the COVID‐19 Pandemic

| Measure | Aggregate Points | No. (%) of Respondents Citing Measure (N = 426) |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced availability of PPE | 1637 | 410 (96.2) |

| Rapid turnaround (< 6 hours) testing | 1362 | 392 (92.0) |

| Testing for COVID‐19 for patients at my discretion (instead of as limited by current protocols) | 1054 | 351 (82.4) |

| Clearer communication about changes in protocols | 976 | 313 (73.5) |

| Assurances that I can take leave to care for myself and family members | 933 | 306 (71.8) |

| Greater clarity regarding my risk for exposure | 858 | 284 (66.7) |

| Assurances that my (and my dependents') medical care will be covered by my employer | 799 | 270 (63.4) |

| Ability to request testing of myself for COVID‐19 even if I do not have symptoms | 787 | 295 (69.2) |

| Assurances about disability benefits | 741 | 243 (57.0) |

| Easily available mental health consultations for myself and other health care providers | 660 | 242 (56.8) |

| Departmental ZOOM or other video sessions to discuss COVID‐19 response and changes | 638 | 236 (55.4) |

Respondents were asked: “From the list below, pick the top 5 measures (1 = highest priority) that you think would alleviate some of your anxiety/stress related to the COVID‐19 pandemic.” Aggregate Points are the sum of points in which 1 (highest priority) = 5 points, 2 = 4 points, 3 = 3 points, 4 = 2 points, 5 = 1 point.

PPE = personal protective equipment.

Discussion

In this cross‐sectional survey conducted during the acceleration phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic, EM physicians in seven cities reported that the pandemic has induced moderate to severe levels of anxiety at work and at home. Their primary work concerns relate to COVID‐19 exposure compromising their personal health, availability of adequate PPE, limited rapid diagnostic testing, and risks of community spread of discharged COVID‐19 patients. Occupational exposure has changed the vast majority of physicians' behavior at home, where they are worried about exposing family members and roommates, the possibility of needing to self‐quarantine, and the effects of excess social isolation. Respondents' highest ranked anxiety relief measures included improved access to PPE, rapid turnaround COVID‐19 testing at provider discretion, clearer communications about COVID‐19 protocol changes, assurances about leave, and ability to request self‐testing.

Although several investigators have examined the effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on health care worker mental health in other countries, we were unable to find any similar studies of U.S. physicians. The moderate to severe levels of stress we found have not been consistently replicated in these other international studies. In a study of 906 health care providers in Singapore and India, with 30% physician enrollment, anxiety was documented in 15.7%, depression in 10.6%, and stress in 5.2% of all study participants. 8 Lu et al. 9 documented higher levels of moderate fear in high‐risk (emergency, critical care, and infectious disease) health care workers at Fujian Provincial Hospital, when compared to low‐risk medical and administrative staff. Our findings are most congruent with those of Lai et al., 3 who found symptoms of depression (50.4%), anxiety (44.6%), insomnia (34.0%), and distress (71.5%) in frontline health care workers at 34 hospitals in China.

Similar to our findings, investigators in China, Italy, and Turkey have reported higher levels of anxiety and depression in female health care providers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 3 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 While investigators in Turkey found that having a child was associated with lower anxiety and depression levels, we did not find a similar protective effect of parenthood or differences in any of the other factors that we examined.

It is important to note that respondents' greatest concern and best anxiety relief measure both related to having adequate PPE. Investigators in China reported that lack of PPE was associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression. Although the availability of PPE has increased substantially over the course of the pandemic, the National Nurses United survey of 8,200 U.S. nurses conducted during the time of our study found that only 55% of nurses had access to N95 respirators on their units and only 24% believed that their employer had sufficient PPE stock for a rapid surge in COVID‐19 patients. 15

Of note, this a longitudinal study with different goals in each of the three phases. In this first phase during the acceleration interval of the COVID‐19 pandemic, we have quantified high levels of work and home life anxiety experienced by EM physicians in the United States, we have identified sources of this stress, and we have presented a number of anxiety mitigation measures. Although some of our findings may be intuitive, this work provides a critical early template for the design and implementation of interventions that will address the mental health needs of emergency physicians in the COVID‐19 pandemic era. Most, if not all, of respondents' measures to relieve stress are readily actionable items for emergency departments (EDs) and their parent institutions, and the central PPE concern is a fundamental workplace safety issue. As discussed by Wong et al., 16 institutions should act expeditiously to address these root cause workplace stressors and consider programs to improve emotional resilience for EM physicians.

In terms of future directions of this work, our study design and survey instruments are fluid. As the pandemic has progressed, additional important stressors, such as childcare and homeschooling demands, the economic impact of declining ED volumes, and changes in health care delivery (lack of personal connections with patients because of limited time in rooms) have arisen. We plan to address these stressors, along with concerns about the development of long‐term posttraumatic stress, in our subsequent follow‐up surveys.

Limitations

Our primary limitation is the moderate response rate of 57%, which we attribute to general e‐mail and clinical work overload during the frenetic early stage of the pandemic and inability to provide gift cards or other incentives in this unfunded study. Although waiting for funding and conducting the survey in a less chaotic time (after the pandemic acceleration phase) may have produced a higher response rate, this method would undoubtedly have introduced recall bias in terms of respondents' self‐assessment of anxiety levels and particular stressors. We believe that our survey provides accurate estimates of how the responding physicians were feeling in real time during the acceleration phase. Another limitation is that those who were experiencing more anxiety may have been more likely to respond to the survey request, thus leading to an overestimation of stress; however, it is also possible that those with more anxiety declined to participate. In terms of spectrum effects, our survey was limited to providers at academic institutions and therefore may not reflect the experience of nonacademic EM physicians.

Additionally, most of our participant sites were in cities in California that had not yet seen large surges of patients as seen in other areas of the country. It is very likely that EM physicians in NYC and other “hot spots” for COVID‐19 have been suffering higher levels of anxiety and effects on home life. Nevertheless, median levels of anxiety in the California sites were similar to those of the New Orleans and Camden sites, which were experiencing surges. This suggests that the impact of COVID‐19 is pervasive and that measures to mitigate stress should be enacted universally.

Conclusions

The acceleration phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic has induced moderate to severe workplace and home anxiety in academic emergency medicine physicians. The pandemic has had considerable impact on the home life of most physicians, especially in terms of decreased signs of affection and worries about exposing family members and friends to infection. Institutional measures, including enhanced availability of personal protective equipment, rapid turnaround testing at provider discretion, and clear communication about COVID‐19 protocol changes, should be enacted to mitigate physician stress.

Supporting information

Data Supplement S1. Supplemental material.

Academic Emergency Medicine 2020;27:700–707.

The authors have no relevant financial information or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author contributions: RMR and RF contributed to study concept, design, and analysis. All authors contributed to data acquisition, interpretation of data, drafting, and revision of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Keeter S. People Financially Affected by Coronavirus Outbreak Are Experiencing More Psychological Distress Than Others. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/30/people-financially-affected-by-covid-19-outbreak-are-experiencing-more-psychological-distress-than-others/. Accessed Apr 9, 2020.

- 2. Nelson LM, Simard JF, Oluyomi A, et al. US public concerns about the COVID‐19 pandemic from results of a survey given via social media. JAMA Intern Med 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetwopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ayanian JZ. Mental health needs of health care workers providing frontline COVID‐19 care. JAMA Health Forum 2020;1:e200397. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA 2020;323:2133–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, et al. The primary care PTSD screen for DSM‐5 (PC‐PTSD‐5): development and evaluation within a Veteran primary care sample. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:1206–11. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prins A, Bovin MH, Kimerling R, et al. Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM‐5 (PC‐PTSD‐5). 2015. Available at: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/screens/pc-ptsd.asp. Accessed Apr 9, 2020.

- 8. Chew NW, Lee GK, Tan BY, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID‐19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:1110.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a cross‐sectional study. Psychiatry Res 2020;288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barello S, Palamenghi L, Graffigna G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID‐19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res 2020;290:113129. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yin Q, Sun Z, Liu T, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms of health care workers during the corona virus disease 2019. Clin Psychol Psychother 2020;27:384–95. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sun D, Yang D, Li Y, et al. Psychological impact of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) outbreak in health workers in China. Epidemiol Infect 2020;148:e96. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xiao X, Zhu X, Fu S, Hu Y, Li X, Xiao J. Psychological impact of healthcare workers in China during COVID‐19 pneumonia epidemic: a multi‐center cross‐sectional survey investigation. J Affect Disord 2020;274:405–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yeni Elbay RY, Kurtulmuş A, Arpacıoğlu S, Karadere E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in Covid‐19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res 2020;290:113130. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. NNU COVID‐19 Survey Results. National Nurses United. 2020. Available at: https://act.nationalnursesunited.org/page/-/files/graphics/0320_NNU_COVID-19_SurveyResults_Updated_031920.pdf. Accessed Apr 29, 2020.

- 16. Wong AH, Pacella‐LaBarbara ML, Ray JM, Ranney ML, Chang BP. Healing the healer: protecting emergency healthcare workers' mental health during COVID‐19. Ann Emerg Med 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.04.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Supplement S1. Supplemental material.