Abstract

Study of immunological features of immune response in 14 children (aged from 12 days up to 15 years) and of 10 adults who developed COVID‐19 show increased number of activated CD4 and CD8 cells expressing DR and higher plasmatic levels of IL‐12 and IL‐1β in adults with COVID‐19, but not in children. In addition, plasmatic levels of CCL5/RANTES are higher in children and adults with COVID‐19, while CXCL9/MIG was only increased in adults. Higher number of activated T cells and expression of IL‐12 and CXCL9 suggest prominent Th1 polarization of immune response against SARS‐CoV2 in infected adults as compared with children.

Keywords: CCL5/RANTES, COVID‐19, CXCL9/MIG, SARS‐CoV‐2, T‐cell activation

To the Editor

COVID‐19 [1, 2] has broad spectrum of manifestations, ranging from mild respiratory illness to severe pneumonia resulting in multiorgan failure and death in adult population. In children, the disease has a mild course characterized by fever, cough, and diarrhea [2, 3, 4]. In addition, the infection can often be asymptomatic in infants in their first year of life despite respiratory diseases such as cystic fibrosis [5, 6]. Despite the large number of children infected by SARS‐Cov‐2, little is known about their immune response.

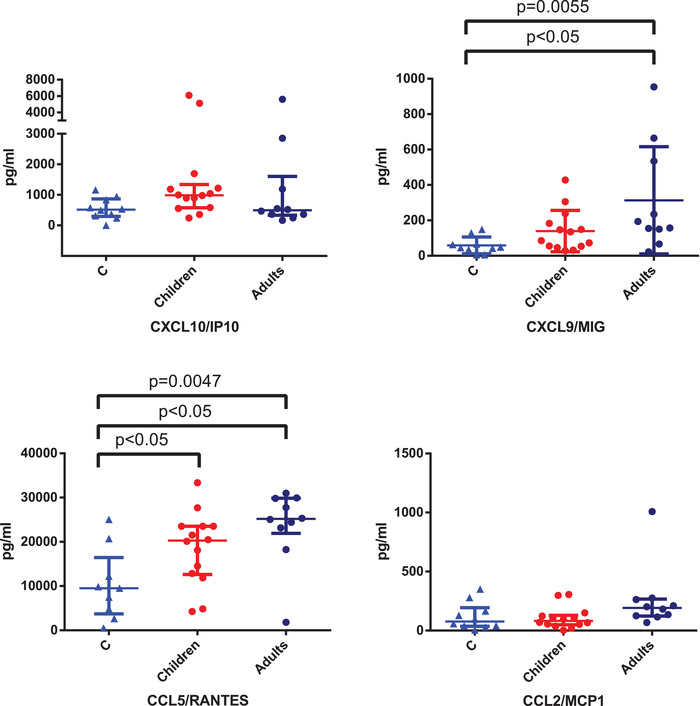

We describe 14 children (P1 to P9; age from 12 days to 15 years) who have been infected during the SARS‐Cov‐2 epidemics and have developed from mild to moderate clinical manifestations (Supporting information Table 1). In order to evaluate the inflammatory response during SARS‐Cov‐2 infection, we measured the levels of chemokines, or cytokines which are produced during viral or bacterial infection and are important in the innate immune response [7]. CXCL10/IP10, CXCL9/MIG, CCL5/RANTES CCL2/MCP‐1, and IL‐8 (CXCL8/IL‐8) were measured on plasma of 14 children and 9 adults with COVID‐19 (Supporting information Table 1). We observed that levels of plasmatic CCL5/RANTES were significantly higher in both children and adults with COVID‐19 as compared to control subjects (Fig. 1). While CXCL9/MIG was higher in adults with COVID‐19 in comparison with control group (Fig. 1). CXCL10/IP10, CCL2‐MCP1, and CXCL8/IL‐8 (data not shown) were detected at comparable levels in the three groups of subjects (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Chemokines and cytokines evaluation in children and adults affected by COVID‐19. Plasmatic levels of CXCL10/IP10, CXCL9/MIG, CCL5/RANTES, and CCL2/MCP‐1 in 14 children, 10 adults with COVID‐19 were measured by Bead Array flow cytometry assay on a single plasma sample at the time of hospital admission, and 10 children with other infections are shown as median ± semi‐interquartile range (pg/ml). Kruskal–Wallis comparison test was used to compare values between healthy control subjects, COVID‐19 children, and adults for analysis of CXCL10/IP10 (NS), CXCL9/MIG (p = 0.0055), CCL5/RANTES (p = 0.0047), and CCL2/MCP‐1 (NS). When the test was statistically significant between three groups, Dunn's multiple comparison test was used for pairwise differences between control group and COVID‐19 children or adults. This was analysis showed significant difference in CXCL9 levels in between COVID‐19 adults and control subjects (p < 0.05), in CCL5 levels between COVID‐19 adults and control subjects (p < 0.05) and between COVID‐19 and control subjects. Nonsignificant (NS) when p > 0.05.

Evaluation of T‐cell subsets revealed CD8 lymphopenia in three children with COVID‐19 (P3, P6, P9). None of the adults with COVID‐19 showed CD4 or CD8 lymphopenia. CD4/CD8 ratio, distribution of naïve, central memory, effector memory, and terminally differentiated CD4 and CD8 cells were normal in children as compared to lymphocyte populations of age‐matched subjects analyzed in recent years for unrelated conditions (Supporting information Tables 2 and 3). However, comparison of terminally differentiated CD8 cells between children and adults infected with SARS‐COV‐2 showed a significantly higher number of this subset in adults subjects (data not shown). To investigate whether T detected in children with COVID‐19 was related to impaired lymphocyte generation from thymus and bone marrow, respectively, we measured T‐cell receptor excision circles (TRECs) and, which are considered biomarkers for adequate new T‐cells production. We observed that the levels of TRECs were within the range of age‐matched control subjects in all children with COVID‐19 (data not shown), suggesting that decrease in lymphocyte counts was probably related to lymphocyte apoptosis or to migration of these cells to affected organs such as the lungs.

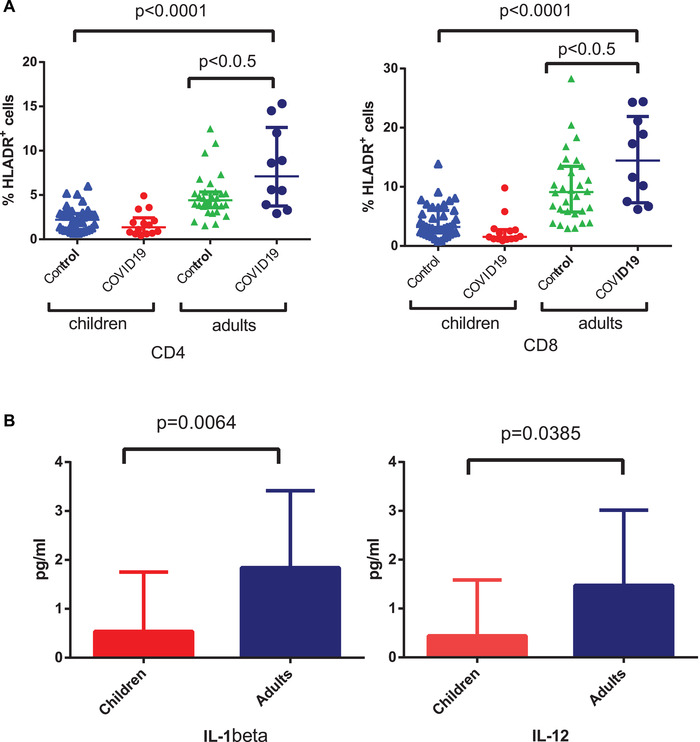

Then, we evaluated the expression of the T‐cell activation marker HLA‐DR in COVID‐19 children and adults as compared to respective age‐matched control groups. We found that the percentage of CD4 and CD8 subsets expressing HLA‐DR was significantly higher in the adults as compared to control subjects, but not in children (Fig. 2, panels A). Additional analyses of HLA‐DR expression by CD4 and CD8 T cells in subjects with dyspnea, including adults (median CD4+/HLA‐DR+: 7.2%; median CD8+/HLA‐DR+: 17.4%) and children (median CD4+/HLA‐DR+: 1.2%; median CD8+/HLA‐DR+: 4.2%), did not show higher activation levels in adults with more severe clinical manifestation as compared with adults (median CD4+/HLA‐DR+: 7.1%; median CD8+/HLA‐DR+: 14.4%) or children (median CD4+/HLA‐DR+: 1.5%; median CD8+/HLA‐DR+: 1.3%) without dyspnea.

Figure 2.

Activation marker expression by T cells in COVID‐19 patients. (A) Expression of HLA‐DR+ (%) in CD4 (left panel) and CD8 (right panel) cells in children and adults with COVID‐19 as compared to respective control subjects and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are shown as median ± semi‐interquartile range (% of cells). HLA‐DR expression was measured on a single blood sample collected at the time of hospital admission. Kruskal–Wallis comparison test was used to compare between healthy control subjects, COVID‐19 children, and adults values of CD4+/HLA‐DR+ cells (p < 0.0001) and of CD8+/HLA‐DR+ cells (p < 0.0001). When the test was statistically significant between three groups, Dunn's multiple comparison test was used for pairwise differences of CD4+/HLA‐DR+ and CD8+/HLA‐DR+ cells between control group and COVID‐19 children or adults. This analysis showed a significant difference in the values of CD4+/HLA‐DR+ and of CD8+/HLA‐DR+ in COVID‐19 adults as compared to control subjects (p < 0.005). (B) Cytokines evaluation in children and adults affected by COVID‐19. Plasmatic levels of IL‐1beta, IL‐12 (p70) in 14 children and 10 adults with COVID‐19 were measured by Bead Array flow cytometry assay on a single plasma sample at the time of hospital admission. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (pg/mL). Mann–Whitney comparison test showed significant differences of IL‐1β and IL‐12 values between COVID‐19 children and adults (p < 0.05).

Next, we measured plasmatic levels of cytokines released during inflammatory or immune response including IF‐α (IFN‐α), IF‐γ (IFN‐γ), IL‐1β, IL‐4, IL‐5, IL‐6, IL‐10, IL‐12 (p70), IL‐17A, and TNF‐α. Remarkably, IL‐12 (p70) and IL‐1β were significantly higher in plasma of COVID‐19 children as compared with adults (Fig. 2B). Likewise, IL‐6, IL‐10, and IL‐5 concentrations were higher in plasma of adults with COVID‐19, while IFN‐α was increased in children, but these differences were not statistically significant (data not shown). Concentrations of IL‐4, IL‐17A were below detection levels in both groups of patients (data not shown).

It is remarkable that lymphopenia was associated with reduction of CD8 cell counts in some patients, while CD4 counts were normal in all subjects, suggesting that CD8 might be mobilized to lymphoid organs or to the lungs. While adults with COVID‐19, especially severe cases can display persistent lymphopenia [8].

Detection of elevated plasmatic levels of CCL5/RANTES at the early stages of SARS‐Cov‐2 infection suggests its potential role in mobilizing T lymphocytes and monocytes to pulmonary tissues where these chemokines are produced at large amounts. CCL5/RANTES mediates recruitment of T lymphocytes and monocytes; it has also been implicated in arterial injury and in sustaining CD8 T‐cell responses during a viral infection [9]. CCL5/RANTES is produced in large amounts by platelets and activated T cells but it is also expressed by respiratory epithelial cells and has been detected in the lungs of patients with SARS‐COV‐2 infection [7].

HLA‐DR expression on CD4 and CD8 cells was lower in children than in adults with COVID‐19 at the time of hospital admission. One might speculate that activated T cells expressing chemokine receptors for CCL5/RANTES are not detected in peripheral blood because these cells were already mobilized to tissues or that innate immune response might be more effective in children. This is consistent with a recent report describing a moderate increase of CD8+ cells coexpressing HLA‐DR and CD38 during COVID‐19 recovery in one adult patient [10]. Alternatively, SARS‐CoV2 viral load might be more elevated in adult subjects as compared to children resulting in stronger T‐cell activation. In addition, we detected higher levels of IL‐12 (p70) and of CXCL9/MIG in adults with COVID‐19 suggesting that prolonged T‐cell activation in adults with COVID‐19 might result in Th1 polarization and possibly in pulmonary tissue damage by activated T cells.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no commercial or financial conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

The study was supported with funds from University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy.

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/eji.202048724

References

- 1. Guan, W.‐J. , et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020. 382: 1–13.31826359 [Google Scholar]

- 2. January, F. , C orrespondence detection of Covid‐19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. 2020. 382: 2019–2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lu, Q. and Shi, Y. , J. Med. Virol. 2020. 0–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zheng, F. , et al. Curr. Med. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kam, K. , et al. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020. 2019–2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Poli, P. , et al. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2020. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Romera‐Liebana, L. , et al. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Romera‐Liebana, L. , et al. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Culley, F. J. , et al. J. Virol. 2006. 80: 8151–8157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Irani, T. , et al. Nat. Med. 2020. 26: 453–455.32284614 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information