Abstract

Background

Best practice for prevention, diagnosis, and management of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is unknown due to limited published data in this population.

Objectives

We aimed to assess current global practice and experience in management of COVID‐19–associated coagulopathy to identify information to guide prospective and randomized studies.

Methods

Physicians were queried about their current approach to prophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment of VTE in patients with COVID‐19 using an online survey tool distributed through multiple international organizations between April 10 and 14, 2020.

Results

Five hundred fifteen physicians from 41 countries responded. The majority of respondents (78%) recommended prophylactic anticoagulation for all hospitalized patients with COVID‐19, with most recommending use of low‐molecular‐weight heparin or unfractionated heparin. Significant practice variation was found regarding the need for dose escalation of anticoagulation outside the setting of confirmed or suspected VTE. Respondents reported the use of bedside testing when unable to perform standard diagnostic imaging for diagnosis of VTE. Two hundred ninety‐one respondents reported observing thrombotic complications in their patients, with 64% noting that the complication was pulmonary embolism. Of the 44% of respondents who estimated incidence of thrombosis in patients with COVID‐19 in their hospital, estimates ranged widely from 1% to 50%. One hundred seventy‐four respondents noted bleeding complications (34% minor bleeding, 14% clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, and 12% major bleeding).

Conclusion

Well‐designed epidemiologic studies are urgently needed to understand the incidence and risk factors of VTE and bleeding complications in patients with COVID‐19. Randomized clinical trials addressing use of anticoagulation are also needed.

Keywords: anticoagulants, bleeding, blood coagulation, COVID‐19, venous thromboembolism

Essentials.

Physicians were surveyed about current venous thromboembolism (VTE) practice patterns.

Anticoagulant recommendations for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) vary.

Estimates of VTE incidence and dose and duration of anticoagulation varied among respondents.

Randomized trials of anticoagulation in patients with COVID‐19 are urgently needed.

1. INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) was first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, and now has infected over 8.6 million people and caused in excess of 460 000 deaths worldwide as of June 20, 2020 (www.statista.com). 1,2 Studies have demonstrated that patients who died of COVID‐19 had higher levels of plasma D‐dimers on admission compared with those who survived. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Furthermore, autopsy studies of patients with COVID‐19 have found fibrin thrombi within the pulmonary vasculature supporting the presence of a hypercoagulable state. 8 , 9 The overall incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients with COVID‐19 is unknown. Studies evaluating incidence have been limited to case reports and case series, with estimates ranging from as low as 1% in the general wards to as high as 69% in intensive care units using screening ultrasound. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 The limited data present a challenge for health care providers in prevention, diagnosis, and management of VTE in patients with COVID‐19. We therefore sought to assess current global practice patterns in the management of COVID‐19–associated coagulopathy and to identify unanswered questions that may guide prospective and randomized studies. We asked clinicians to share their experience and recommendations about thromboprophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment of VTE in patients with COVID‐19.

2. METHODS

Physicians were surveyed using an online survey tool (SurveyMonkey). The survey was sent by email to members of the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society, Venous thromboEmbolism Network US, the Latin American Cooperative Group for Hemostasis and Thrombosis, Unit for Thrombosis and Hemostasis at the Hospital de Clínicas in Uruguay, the Mexican Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis, the Asia Pacific Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, the Thrombosis and Haemostasis Society of Australia and New Zealand, the Irish Network for VTE Research, and the ISTH between April 10 and 14, 2020. Social media links were also provided. The survey was written in English, but the introduction was translated into Spanish for the Latin American Thrombosis and Hemostasis societies. The survey included direct questions, with the option of writing in a response if a specific one was not provided in the selections listed (see Appendix S1). Topics of the 28‐question survey included estimates of thrombotic and hemorrhagic complications, management of various clinical scenarios in patients with COVID‐19, type and intensity of anticoagulation, and laboratory testing and diagnostic approaches. Multiple selections were permitted (such that the combined percentage in each question could exceed 100%) given the complexity of potential scenarios. Demographics of respondents collected included practice patient population (adult or pediatric), practice location, country of practice, and years of experience.

Survey results were summarized using descriptive statistics. Student t tests and chi‐square tests were used to evaluate for associations between responses to questions and demographic factors or between survey responses.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics of respondents

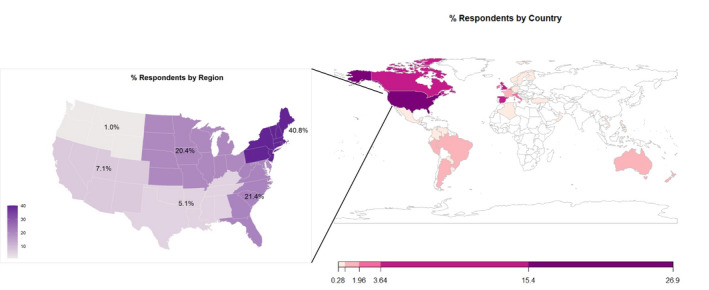

Five hundred fifteen participants answered at least one question on the survey and 71% of participants completed the survey. Baseline characteristics of survey respondents are listed in Table 1 and Figure 1. Based on the responses of 278 respondents that listed their affiliated hospital, 266 hospitals were represented across 41 countries.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and characteristics of survey respondents

| Characteristic | Number of respondents |

|---|---|

| Country | n = 357 (%) |

| United States | 96 (26.9) |

| Spain | 55 (15.4) |

| United Kingdom | 51 (14.3) |

| Canada | 48 (13.5) |

| Ireland | 13 (3.6) |

| Belgium | 10 (2.8) |

| Italy | 9 (2.5) |

| Australia | 7 (2.0) |

| Peru | 6 (1.7) |

| Netherlands | 5 (1.4%) |

| New Zealand | 5 (1.4) |

| Argentina | 5 (1.4) |

| France | 4 (1.1) |

| Other | 43 (12.0) |

| Practice | n = 353 (%) |

| Adult | 305 (86.4) |

| Adults/Pediatrics | 37 (10.5) |

| Pediatrics | 11 (3.1) |

| Specialty | n = 347 (%) |

| Hematology | 224 (64.6%) |

| General internal medicine/Hospitalist | 69 (19.9) |

| Pulmonary/Critical care | 38 (11.0) |

| Vascular medicine | 24 (6.9) |

| Cardiology | 18 (5.2) |

| Medical ncology | 15 (4.3) |

| General pediatrics | 4 (1.2) |

| Years in practice | n = 352 (%) |

| <5 | 44 (12.5) |

| 5‐10 | 62 (17.6) |

| 11‐15 | 62 (17.6) |

| 16‐20 | 52 (14.8) |

| >20 | 132 (37.5) |

| Number of patients who are COVID positive at practicing hospital | n = 365 (%) |

| <100 | 134 (36.7) |

| 100‐250 | 84 (23.0) |

| 251‐500 | 68 (18.6) |

| 501‐1000 | 41 (11.2) |

| 1001‐3000 | 18 (4.9) |

| >3000 | 5 (1.4) |

| Unknown | 15 (4.1) |

| Number of patients cared for who are COVID positive | n = 361 (%) |

| <10 | 180 (49.9) |

| 11‐25 | 85 (23.6) |

| 26‐50 | 43 (11.9) |

| 51‐100 | 35 (9.7) |

| 101‐250 | 14 (3.9) |

| 251‐500 | 3 (0.8) |

| >500 | 1 (0.3) |

COVID, coronavirus disease 2019.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of survey respondents by county. Respondents from the United States were identified by region. This figure represents the nationalities reported by each respondent. The expanded area is the breakdown of United States by region

3.2. Anticoagulation

All of the participants provided responses to the question to whom they would recommend thromboprophylaxis. The majority of respondents (78%) recommended prophylactic anticoagulation for all hospitalized patients with COVID‐19, while 43% also selected that they would follow institutional guidelines for criteria for prophylaxis. Eight percent of respondents recommended thromboprophylaxis for all patients with COVID‐19, irrespective whether inpatient or outpatient. Multiple selections for choice of anticoagulant were allowed. Of the 453 respondents who indicated use of low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) for thromboprophylaxis, 61% (n = 278) recommended fixed‐dose LMWH, and 62% (n = 281) recommended weight‐adjusted LMWH. One‐third recommended unfractionated heparin (UFH) (22% prophylactic fixed dose and 12% weight‐adjusted dose). Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) were recommended by 6% (n = 27), with another 6% recommended a variety of other regimens including escalated doses of LMWH for all patients or based on D‐dimer or disease severity.

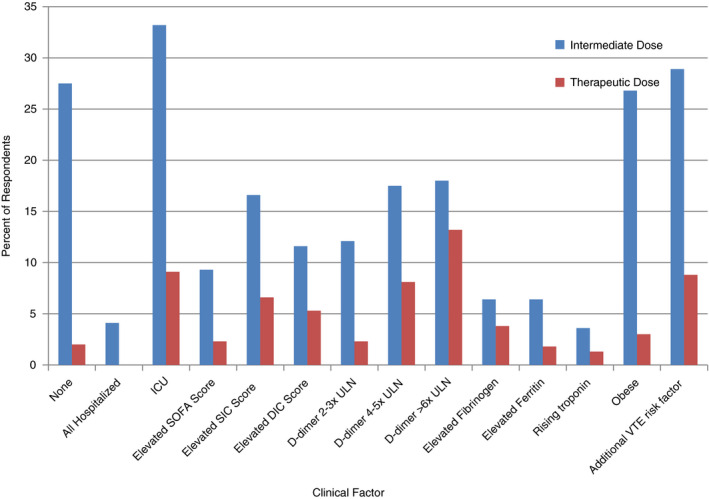

In response to when dose escalation of prophylactic anticoagulation to intermediate dose was considered, 28% (n = 122) of respondents did not recommend escalated doses of prophylactic anticoagulation for any indication (Figure 2). If recommended, a variety of factors were used to select patients for dose escalation (Figure 2), and LMWH was the most commonly mentioned agent (98%; n = 279) followed by UFH (26%; n = 73). Recommendations to escalate to intermediate dosing did not differ between physicians practicing in the United States and other countries, between providers practicing in hospitals with <250 patients who were COVID positive or >250 patients who were COVID positive, or between hematologists and other medical specialties. Eighty‐two percent of physicians recommending dose escalation also noted that their patients experienced thromboembolism compared to 69% of physicians who did not recommend intermediate prophylaxis (P < .01).

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of survey respondents recommending escalated doses of anticoagulation to intermediate or therapeutic dosing based on clinical scenarios. This figure highlights the indications for which respondents would elect to escalate prophylactic anticoagulation to intermediate or therapeutic doses. DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; ICU, intensive care unit; SIC, sepsis‐induced coagulopathy; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; ULN, upper limit of normal; VTE, venous thromboembolism

Recommendations for escalation to a therapeutic dose of anticoagulation was reported by 398 (77%) of respondents. Indications for dose escalation included a new diagnosis of atrial fibrillation or VTE (86%; n = 341) and high clinical suspicion of VTE but unable to obtain diagnostic testing (78%; n = 310). No respondents reported that they would escalate to therapeutic anticoagulation in all patients hospitalized with COVID‐19, while 2% reported that there was no indication that would lead them to escalate to therapeutic anticoagulation (Figure 2). Other indications for which respondents would escalate to therapeutic doses of anticoagulant therapy varied, including some respondents using certain clinical scoring systems to guide escalation to full‐dose anticoagulation (Figure 2). In addition, seven respondents reported clotting of circuits such as continuous renal replacement therapies (CRRT), dialysis filters, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) catheters leading them to recommend escalation to therapeutic anticoagulation for those affected patients. Ninety‐six percent of the 391 respondents recommended LMWH, 48% UFH, 27% DOACs, 13% vitamin K antagonists, 10% fondaparinux, and 7% intravenous (IV) direct thrombin inhibitors for therapeutic anticoagulation.

Extended VTE prophylaxis (after discharge), depending on the presence of risk factors, was recommended by 276 of the 449 (62%) respondents who answered this question. The most common risk factor for recommending this approach was a history of VTE before COVID‐19 (31%, n = 141), but other indications included a history of cancer (24%; n = 109), patients who required admission to the intensive care unit (ICU; 22%; n = 98), and patients meeting inclusion criteria of prior trials for extended prophylaxis for medically ill patients (21%; n = 93). Other risk factors identified include hospitalization for COVID‐19 (20%; n = 87), D‐dimer greater than two times the upper limit of normal (ULN; 18%; n = 79), obesity (15%; n = 69), and pregnancy (12%; n = 54). Most respondents recommend LMWH (78%, n = 207) for extended VTE prophylaxis, followed by rivaroxaban (32%; n = 86), apixaban (24%; n = 65), and betrixaban (2%, n = 6). Recommendations for extended prophylaxis did not differ between physicians practicing in the United States and other countries but was more often recommended by those who practiced in hospitals with more than 250 COVID‐19 admissions (67% vs 54%; P = .02), hematologists/oncologists compared to other medical specialties (67% vs 47%; P < .01), or from physicians who noted their patients experienced thrombotic complications (66% vs 38%; P < .01).

3.3. Diagnosis

Three hundred ninety‐one (75%) participants responded to questions regarding using compression ultrasound (CUS) to diagnose deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in patients who are COVID‐19 positive. Eighty percent reported obtaining CUS only in patients with clinical symptoms of DVT, 17% of participants reported testing based on the D‐dimer results, and 8% reported testing in all ICU patients (some even reported monitoring periodically or based on D‐dimer trends). An additional 2% reported obtaining CUS in all patients upon hospital admission. If unable to obtain standard imaging, 59% reported diagnosing patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) based on worsening respiratory status or right‐heart strain on bedside echocardiogram. Fifty‐five percent reported using hemodynamic instability, 48% reported unilateral limb swelling, and 42% reported using clinical scoring tools. An additional 35% reported using increasing D‐dimer, 11% reported IV‐line malfunction or increase in ventilated to perfused lung areas (ie, dead space), and 5% reported the need for proning as surrogates for thrombosis.

3.4. COVID‐19 laboratory monitoring

Three hundred ninety‐two (76%) respondents answered questions regarding baseline laboratory ordering practices, while 380 answered questions regarding ongoing laboratory monitoring. The most frequent baseline laboratory test ordered was a complete blood cell count (CBC; 93.9%). Laboratory tests ordered at baseline by more than 75% of respondents included D‐dimer, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), fibrinogen, and C‐reactive protein (CRP). Additional laboratory tests frequently ordered included baseline basic metabolic panel (BMP) or comprehensive metabolic panel, ferritin, and lactate dehydrogenase. Similarly, the most frequent laboratory tests ordered to monitor COVID‐19 patients at least three times per week was a CBC. Additional laboratory tests ordered at least three times per week by >50% of respondents included BMP, D‐dimer, PT, aPTT, fibrinogen, and CRP. The infrequently ordered (<5%) coagulation tests at baseline or for routine monitoring included antithrombin activity, ADAMTS‐13 activity, antiphospholipid antibodies (APLAs), thromboelastography, troponin, and von Willebrand factor activity. Finally, when asked about changes in practice, several respondents indicated a shift from monitoring UFH using aPTT to monitoring with anti‐Xa levels, while some respondents indicated incorporating the practice of using anti‐Xa levels to monitor dosing of prophylactic or therapeutic LMWH.

4. OUTCOMES

4.1. Bleeding complications

Questions about bleeding complications were answered by 377 (73%) physicians. Over half (n = 203) reported they had witnessed no bleeding complications, minor bleeding was reported by 34% (n = 129), clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding by 14% (n = 54), and major bleeding by 12% (n = 46). The most common bleeding sites reported included cutaneous/line related (41%; n = 65), mucous membranes (41%; n = 65), gastrointestinal (27%; n = 43), hemoptysis/alveolar hemorrhage (22%; n = 35), genitourinary (16%; n = 27), retroperitoneal (13%; n = 21), neurologic (10%; n = 16), and muscular (3%; n = 2). Bleeding complications were most often reported in patients on therapeutic anticoagulation (65%; n = 97), followed by intermediate (27%; n = 41) or prophylactic dose (41%; n = 62). Nine percent of respondents reported that bleeding occurred without anticoagulation.

4.2. Thrombotic complications

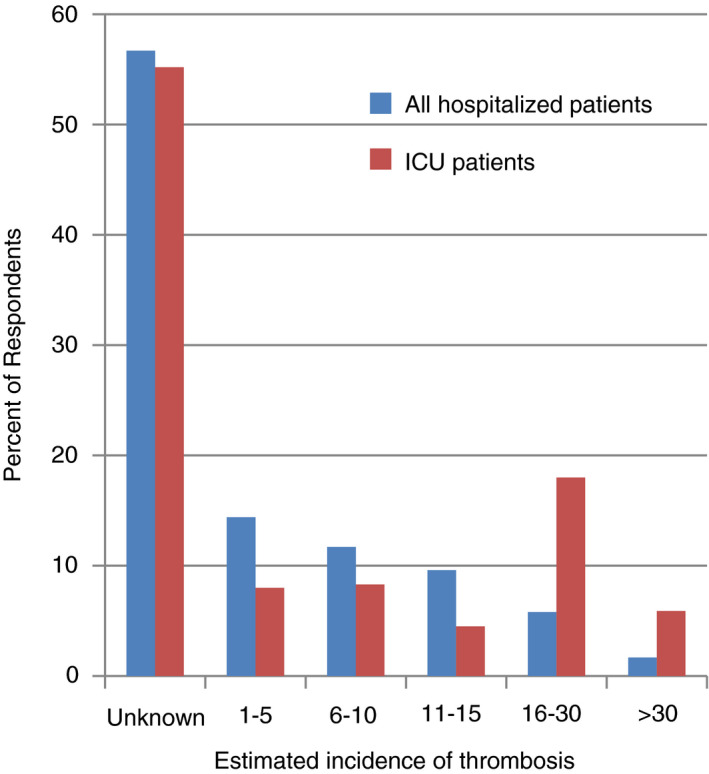

When queried about the approximate incidence of VTE in patients with COVID‐19, 56% of the 293 and 55% of the 290 participants did not know the incidence in their hospitalized and ICU patients, respectively (Figure 3). Of the respondents who estimated the incidence of thrombosis, approximates ranged from 1% to >50% (Figure 3). Incidence of thrombosis was estimated to be higher in ICU patients compared to all hospitalized patients (P = .02). Of the 261 respondents who provided what dose of anticoagulation patients were on when thrombotic complications occurred, 39% (n = 101) reported none, 84% (n = 218) reported prophylactic, 18% (n = 47) reported intermediate, and 11% (n = 30) reported therapeutic dose.

FIGURE 3.

Reported incidence of thrombosis in hospitalized and ICU patients with COVID‐19. This figure represents the estimated incidence of thrombosis, reported by each respondent, for all hospitalized patients and ICU patients. COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; ICU, intensive care unit.

Of the 367 respondents who reported on thrombotic complications, 21% (n = 76) reported no thrombotic complications in their COVID‐19 patients. The majority of thrombotic complications reported were PE (64%; n = 234) followed by lower‐extremity DVT (49%; n = 181), upper‐extremity DVT (19%; n = 71), and superficial vein thrombosis (9%; n = 34). Few participants identified thrombosis in unusual locations with 5% (n = 19) reporting intracardiac thrombosis, 3% (n = 11) splenic vein thrombosis, and 4% (n = 13) cerebral vein thrombosis. For arterial thrombosis, 20% (n = 75) of respondents reported ischemic stroke, 12% (n = 52) myocardial infarction, and 9% (n = 34) peripheral artery embolism had occurred in their patients. Twenty nine percent (n = 105) of respondents reported a high clinical suspicion for VTE in patients for whom they were unable to obtain diagnostic testing. In addition, 16% (n = 59) reported sudden death with concern for thrombosis. For adjunctive therapies, 12% (n = 45) reported thrombotic complications associated with mechanical circulatory support (ie, ECMO, ventricular assist device), and 25% (n = 90) reported these complications with dialysis or CRRT.

5. DISCUSSION

The COVID‐19 pandemic has affected all countries and has required rapid adaptation to clinical practice with limited published evidence. Our survey identified several areas with consensus on management of COVID‐19, including the use of therapeutic anticoagulation for all confirmed or clinically suspected VTE and universal use of thromboprophylaxis for all hospitalized patients. Common VTE risk factors identified that might prompt consideration of higher‐dose prophylaxis or extended prophylaxis included ICU care and cancer. Most clinicians recommended LMWH or UFH as anticoagulants of choice.

Many organizations including American Society of Hematology (ASH), ISTH, World Health Organization, American College of Cardiology (ACC), Anticoagulation Forum, British Thoracic Society, and CHEST have published guidance for the prevention of VTE in patients with COVID‐19 (Table 2). 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 These guidance statements recommend standard thromboprophylaxis in all hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 infection unless a strong contraindication is present. Our survey responses reflect adoption of this guidance into practice. The use of LMWH as the most commonly recommended regimen is also consistent with published guidance. LMWH in addition to heparin has been shown to have anti‐inflammatory properties, which may be an added benefit in COVID‐19 infection where proinflammatory cytokines are markedly elevated. 39 , 40 , 41

TABLE 2.

Summary of recommendations in VTE prophylaxis from various guidance and survey responses for patients with COVID‐19

| Study | Acutely ill; no bleeding risk | Critically ill; no bleeding risk | Acute or critically ill with bleeding | Acute or critically ill with CrCl < 30 mL/min | Escalation from prophylactic dose to therapeutic or intermediate dose | Extended prophylaxis post discharge (criteria, agent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASH‐FAQ 33 | LMWH or fondaparinux favored over UFH to reduce contact unless the risk of bleeding is judged to exceed the risk of thrombosis | Same as acutely ill and recommend participation in well‐designed clinical trials and/or epidemiologic studies when available | Mechanical prophylaxis | UFH (twice daily to three times daily) |

Unknown in critically ill Reasonable to consider in patients who experience recurrent clotting of access devices Recommend participation in well‐designed clinical trials and/or epidemiologic studies when available. |

Consider based on inclusion criteria from previous trials (eg, combination of age, comorbidities, and D‐dimer >2 times ULN). Any decision needs to consider VTE risk factors (including reduced mobility) and bleeding risk as well as feasibility. |

| Anticoagulation forum 36 | Standard‐dose VTE prophylaxis as per existing societal guidelines |

Suggest increased doses of VTE prophylaxis (intermediate dose LMWH/UFH or low‐intensity UFH infusion), based largely on expert opinion. Reasonable to employ both pharmacologic and mechanical VTE prophylaxis if no contraindication |

Mechanical prophylaxis with regular reassessment for conversion to pharmacologic prophylaxis. | Dose adjust for renal function | Suggest against intensification of anticoagulant dosing based only on biomarkers. However, acutely worsening clinical status in conjunction with laboratory value changes, may necessitate further thromboembolic workup or empiric treatment. | Consider on a case by case basis in patients with ongoing VTE risk factors and low bleeding risk. |

| ACC 28 | LMWH may be advantageous over UFH to reduce exposure | LMWH may be advantageous over UFH to reduce exposure | Mechanical prophylaxis | UFH (twice daily to three times daily) |

Insufficient data Majority reccommend against escalation 32% favored intermediate and 5% therapeutic |

Consider up to 45 d if elevated VTE risk without high bleeding risk. Panelist breakdown if considering: 51% DOAC 24% LMWH |

| ISTH 29 | LMWH in the absence of any contraindications (active bleeding and platelet count <25 × 109/L | LMWH in the absence of any contraindications (active bleeding and platelet count <25 × 109/L | Not Specified | UFH (twice daily to three times daily) | Escalation to therapeutic if presumed VTE | Not specified |

| SSC of the ISTH 35 |

Standard‐dose UFH or LMWH should be used after careful assessment of bleed risk, with LMWH as the preferred agent a Intermediate‐dose LMWH may also be considered (30% of respondents) |

Prophylactic‐dose UFH or LMWH. Intermediate‐dose LMWH (50% of respondents) can also be considered in high‐risk patients Multimodal thromboprophylaxis with mechanical methods should be considered (60% of respondents) |

Mechanical thromboprophylaxis | VTE prophylaxis recommendations should be modified based on deteriorating renal function |

Patients with obesity as defined by actual body weight or BMI should be considered for a 50% increase in dose of thromboprophylaxis Treatment‐dose heparin should not be considered for primary prevention until results of randomized controlled trials are available |

Consider for all hospitalized patients that meet high VTE risk criteria Either LMWH (30%) or a DOAC (ie, rivaroxaban or betrixaban 30% of respondents can be used. Duration can be approximately 14 d at least (50% of respondents), and up to 30 d (20% of respondents) |

| BTS 31 |

Standard risk: prophylactic LMWH (daily) High risk: LMWH (twice daily) |

Standard risk: prophylactic LMWH (daily) High risk: LMWH (twice daily) |

Not specified | Not specified |

Not possible to advocate any particular escalation approach and suggest developing local protocols for risk stratification in patients with COVID‐19 Consider intermediate dose in high risk patients and therapeutic in proven or suspected acute VTE. |

Consider in high‐risk patients (h/o VTE, cancer, reduced mobility, or ICU admission) and if risk of VTE is greater than risk of bleeding If considering: prophylactic LMWH or DOAC |

| Thrombosis‐UK/BSH 32 ,65 | LMWH or fondaparinux according to license | LMWH + mechanical compression stockings | Mechanical prophylaxis (in bleeding and if platelets <30 × 109/L) | UFH (twice daily to three times daily) or reduced dose LMWH | Therapeutic for presumed PE | Not specified |

| Dutch 50 | Prophylactic LMWH irrespective of risk score | Prophylactic LMWH irrespective of risk score | Not specified | Not specified |

Therapeutic if VTE is confirmed If imaging not possible and D‐dimer increases progressively, consider therapeutic AC |

Not specified |

| Chinese 30 | Use Padua or IMPROVE RAM to calculate risk and if high or moderate risk, LMWH recommended. | LMWH over UFH | Mechanical Prophylaxis | UFH (BID) | If VTE suspected and unable to be confirmed due to restricted conditions, curative anticoagulation recommended in absence of contraindications |

Consider if persistent risk of VTE at time of discharge LMWH favored over DOAC due to potential drug‐drug interactions and/or frequent comorbidities |

| CHEST 34 | LMWH or fondaparinux over UFH b ; and LMWH, fondaparinux or UFH over DOAC c | LMWH over UFH b ; and LMWH or UFH over fondaparinux or DOAC c | Mechanical prophylaxis | Not specified | Insufficient data to justify increased‐intensity anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis in the absence of randomized controlled trials | Extended thromboprophylaxis in patients at low risk of bleeding should be considered, if emerging data on the postdischarge risk of VTE and bleeding indicate a net benefit of such prophylaxis |

| VENUS Survey |

78% VTE prophylaxis 61% LMWH 33% UFH 6% DOAC |

33% use intermediate dose in ICU patients 9% use therapeutic dose in ICU patients |

Not specifically queried | Not specifically queried |

28% no escalation 72% escalation for select patients |

39% no postdischarge, 61% postdischarge (risk factors including ICU stay, D‐dimer, obesity, cancer, h/o VTE) Respondent breakdown: 78% LMWH, 24% apixaban, 2% betrixaban, 32% rivaroxaban |

ACC, American College of Cardiology; ASA, aspirin; ASH, American Society of Hematology; BMI, body mass index; BTS, British Thoracic Society; COVID‐19, coronavirus 2019; CrCl, creatinine clearance; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; FAQ, frequently asked questions; H/o, history of; ICU, intensive care unit; LMWH, low‐molecular‐weight heparin; N/A, not applicable; RAM, risk assessment models; SIC, sepsis‐induced coagulopathy; SSC, Scientific and Standardization Committee; SSH, Swedish Society of Hematology; UFH, unfractionated heparin; ULN, upper limit of normal; VENUS, Venous thromboEmbolism Network United States; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

VTE prophylaxis recommendations should be modified based on extremes of body weight, severe thrombocytopenia (ie, platelet counts of 50 000 × 109/L or 25 000 × 109/L). DOACs should be considered with caution as coadministration of immunosuppressant, antiviral and other experimental therapies may potentiate or interfere with DOAC therapy.

Favors this approach to limit staff exposure.

Cautions against the use of DOACs in these patients secondary to the high risk of rapid clinical deterioration in these patients.

Our study also demonstrated significant differences in practice patterns such as the decision to escalate the dose of anticoagulation and/or to consider extended prophylaxis and in the use of laboratory monitoring. The indication to consider dose escalation from prophylactic to intermediate doses of anticoagulation is a subject of debate that is not currently informed by high‐quality data. International guidance reflects this discrepancy in practice, with some organizations suggesting intermediate‐dose anticoagulation for prophylaxis, whereas others have not (Table 2). Escalation to intermediate dosing for thromboprophylaxis in ICU patients may be based on the limited existing data that suggests ICU patients have a higher risk of VTE than non–critical care patients (Table 3). Almost one‐third of our respondents recommended dose escalation in obese patients, likely based on prior studies: One retrospective analysis demonstrated decreased VTE incidence in obese patients with escalated prophylactic dosing, 42 and another showed that weight‐based dosing of enoxaparin, 0.5 mg/kg twice daily, achieved higher anti‐Xa levels in obese patients compared to prophylactic or fixed dosing. 43 However, major VTE guidelines have not addressed weight‐based dosing due to lack of randomized data, and additional studies are needed.

TABLE 3.

Published studies evaluating incidence of VTE in patients with COVID‐19

| Study | Country | Study design | N | Population | Anticoagulant and dose | Rate of VTE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klok et al 12 , 53 | Netherlands | Retrospective cohort | 184 | ICU | Prophylactic or intermediate |

Original cumulative incidence of VTE and ATE (median of 7 d): 31%. (VTE: 27%) Updated cumulative incidence of VTE and ATE (median 14 d) a : 49% |

| Cui et al 10 | China | Retrospective cohort | 81 | ICU | None | 25% (20/81) (DVT) |

| Helms et al 19 | France | Prospective cohort | 150 | ICU |

Prophylactic: 70% Therapeutic: 30% |

18.7% (28/150) |

| Poissy et al 13 | France | Retrospective cohort | 107 | ICU |

Prophylactic: 91% Therapeutic: 9% |

15‐d cumulative incidence: 20.4% (PE) |

| Desborough et al 17 | United Kingdom | Retrospective cohort | 66 | ICU |

Prophylactic: 83% Therapeutic: 17% |

15% (10/66) PE in 30 d |

| Fraissé et al 18 | France | Retrospective cohort | 92 | ICU |

Prophylactic: 47% Therapeutic: 53% |

31/92 (33.7%) |

| Thomas et al 24 | United Kingdom | Retrospective cohort | 63 | ICU | Prophylactic | Cumulative incidence: 27% |

| Llitjos et al 20 | France | Retrospective cohort | 26 |

ICU Screening 100% |

Prophylactic: 31% Therapeutic: 69% |

69% (18/26) |

| Longchamp 27 | France | Retrospective cohort | 25 |

ICU Screening 100% |

Prophylactic: 92% (weight‐based) Therapeutic: 8% |

32% (8/25) |

| Nahum et al 23 | France | Retrospective cohort | 34 |

ICU Screening 100% |

Prophylactic | 27/34 (79%) |

| Voicu et al 25 | France | Prospective cohort | 56 |

ICU Screening 100% |

Prophylactic: 78% Therapeutic: 13% |

26/56 (46%) DVT |

| Middeldorp et al 22 | Netherland | Retrospective cohort | 75 |

ICU Screening 27% |

Prophylactic or intermediate | 21‐d cumulative incidence a : 59% (symptomatic: 34%) |

| Goyal et al 11 | United States (New York) | Retrospective cohort | 393 |

Invasive mechanical ventilation Noninvasive mechanical ventilation |

Not specified |

7.7% (10/130) 3/263 (1.1%) |

| Lodigiani et al 21 | Italy | Retrospective cohort | 388 |

ICU: 16% Regular ward: 84% |

Prophylactic, intermediate, or therapeutic (100% in ICU, 75% in ward) | Cumulative rate (VTE + ATE) 21% (27.6% ICU, 6.6% ward) |

| Bompard et al 15 | France | Retrospective cohort | 135 |

ICU (18%) Regular ward (35%) ER (47%) |

Prophylactic or intermediate (obese and ICU) in inpatients |

Total 32/135 (24%) PE ICU 50% Others 18% |

| Al‐Samkari et al 7 | United States (Boston) | Retrospective cohort | 400 |

ICU (36%) Regular ward (64%) |

Prophylactic |

Total: 4.8% radiographically confirmed VTE (4.13 per 100 patient‐weeks) ICU – 7.6% (4.76 per 100 patient‐weeks) Regular ward‐ 3.1% (3.49 per 100 patient‐weeks) |

| Zhang et al 26 | China | Retrospective cohort | 143 |

Regular ward Screening 100% |

Prophylactic: 37.1% | 66/143 (46.1%) LE DVT |

| Middeldorp et al 22 | Netherland | Retrospective cohort | 123 |

Regular ward Screening 27% |

Prophylactic | 21‐d cumulative incidence of both any VTE and symptomatic VTE a : 9% |

| Artifoni et al 14 | France | Retrospective cohort | 71 |

Regular ward Screening 100% |

Prophylactic | 16/71 (22.5%) [including 7 (9.8%) PE] |

| Demelo‐Rodriguez et al 16 | Spain | Prospective cohort | 156 |

Regular ward Screening 100% |

Prophylactic: 98% | 23/156 (14.7%) DVT |

ATE, arterial thrombotic event; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; ER, emergency room; ICU, intensive care unit; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

These studies released updates or were finalized after the surveys were submitted.

We also found that while the majority of respondents recommended escalation to therapeutic anticoagulation only in those with confirmed or high suspicion of VTE, a small number of clinicians recommended escalation to therapeutic anticoagulation in patients with additional risk factors (such as elevated D‐dimer). The risks and benefits of this approach remain unknown and several multicenter international trials are under way to address the utility of escalating doses of anticoagulation in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19.

There is also uncertainty in the role for extended prophylaxis. While the majority of respondents (62%) recommended this practice for selected patients with COVID‐19, there were a variety of clinical factors influencing this practice. Furthermore, while LMWH was the most commonly recommended agent for extended prophylaxis, additional anticoagulants, including various DOACs, were suggested. These responses highlight the variability of current clinical practice and the uncertainty surrounding optimal management. The role for extended prophylaxis following hospitalization has been previously studied because of a high percentage of VTE events (as high as 57%) occurring after hospital discharge. 44 Two DOACs, rivaroxaban and betrixaban, have been approved for extended prophylaxis (30‐45 days); 45 , 46 however, they are not approved or reimbursed for this indication in all countries, and how often these regimens are used in practice remains unclear. Moreover, our study demonstrates that the acutely ill population in these studies are not the only factors influencing the decision to recommend extended prophylaxis. Extended VTE prophylaxis has been shown to be beneficial in clinical settings such as following orthopedic surgery, and abdominal and pelvic surgery for patients with cancer, 47 as well as in high‐risk ambulatory patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. 48 , 49

Our study supports that clinicians are concerned that patients with COVID‐19 are at increased risk of VTE, leading to recommendations for a role for extended thromboprophylaxis following discharge; a practice that is considered in many guidelines. 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 50 However, almost 40% of providers do not recommend VTE prophylaxis after hospital discharge. Our survey also highlights a variability in current practice on the type of anticoagulant used following hospital discharge. This variability may reflect local availability and costs of different drugs across different regions and countries. In addition, the need for thromboprophylaxis in patients who are COVID‐19 positive treated as outpatients is another commonly encountered question for clinicians, and practices vary. Prospective studies are needed to better define the management of extended prophylaxis in patients with COVID‐19.

This survey also draws attention to some of the challenges in diagnosing VTE events. Patients’ clinical instability and the scarcity of personal protective equipment may affect the ability to obtain prompt diagnostic imaging. In addition, renal function can be compromised in patients with severe COVID‐19 infection and limit imaging requiring contrast. The majority of the participants report using bedside Doppler ultrasound and echocardiogram to diagnose a VTE. Case reports have highlighted the importance of awareness for PE as a potential cause for acute decompensation in patients with COVID‐19. 51 Consensus recommendations from Obi et al 52 provide practical guidance in the diagnosis and treatment of VTE in patients with COVID‐19 if imaging is unavailable. As is practiced by almost 80% of respondents, empiric anticoagulation without confirmatory imaging should be considered in patients with a high clinical suspicion of VTE while balancing the risk of bleeding.

The number of studies reporting VTE continues to increase, although rates of VTE vary dramatically (Table 3). Our survey responses reflect the differences and heterogeneity in the literature currently available. When screening ultrasound was performed on admission, Llitjos et al 20 reported a cumulative incidence of VTE of as high as 69%, 23% of which were PE, despite 30% of patients receiving prophylactic anticoagulation and 70% receiving therapeutic anticoagulation. In another study of three ICUs in the Netherlands, Klok et al 12 , 53 reported a cumulative rate of all thrombosis of 49%, despite all the patients receiving a prophylactic dose of anticoagulation. However, it is important to note that the prophylactic LMWH dose initially used in two of the three ICUs was lower than what is recommended by the manufacturer. 54 In another study in ICUs in France, when compared with a matched historical control of patients who do not have COVID‐19 but have acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), patients with COVID‐19 with ARDS had a 2.6‐fold increased odds of thromboembolic complications and a 6‐fold increased odds of PE. 19 In contrast to these high rates of VTE, retrospective reports from the United States found much lower rates of VTE. In 393 consecutive patients admitted to two New York hospitals, the rate of VTE in patients on mechanical ventilation was only 7.7%, and in the first 400 patients admitted to five affiliated Boston hospitals, the overall rate of VTE in ICU patients was similar, at 7.6%. 7 , 11 Differences in the VTE incidence may be reflective of differences in screening, disease severity (such as ICU status), patient characteristics, or other concurrent therapies, or detection of immunothromboses that are counted as PE instead of in situ thrombosis, and other factors that have yet to be identified. 55 An online COVID registry of thrombosis is being planned, and although observational, it aims to provide representative data on the magnitude of this problem. 56

Not to be overlooked, anticoagulation, particularly with intermediate or therapeutic doses, may increase the risk of bleeding. Hemorrhage was not initially perceived as a major complication in most studies of patients with COVID‐19; however, more recent studies have reported higher numbers. In a study of 150 French ICU patients, only 4 (2.7%) were reported to have bleeding complications, which included intracerebral hemorrhage and extracorporeal circulation cannula hematoma. 19 In the Boston area study, the overall rate of hemorrhage was 4.8%, which was similar to the overall rate of VTE reported. 7 In a recent study from the United Kingdom of patients admitted to a critical care unit, 11% suffered from a major bleed. 17 Similarly, in a French study of 92 ICU patients, the overall rate of hemorrhagic events was 21%, and notably, 84% of those were on therapeutic anticoagulation. 18 In the current survey, 43% of respondents noted that their patients had bleeding complications. Importantly, this response does not reflect a true bleeding incidence; it is the percentage of bleeding per respondent and not per patient. Furthermore, it may be influenced by recall bias in our survey, lack of documentation of bleeding complications in previous studies, and difficulty with obtaining data on hemorrhage without intensive chart review. The majority of bleeding events (65%) were reported to be on therapeutic anticoagulation, which is similar to what has been described in the latest studies. In a recent nationwide data set from China, patients found to have a high risk of VTE using the Padua Prediction Score on admission were also found to have a high risk of bleeding. 57 Thus, attention should be paid to the balance of bleeding and thrombosis in the management of patients with COVID‐19, and more studies evaluating these risks are much needed.

Laboratory monitoring of hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 provides a means to guide care but also may provide predictive and prognostic information. One of the most commonly reported abnormal laboratory findings in patients with COVID‐19 is highly elevated D‐dimer levels. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Others include elevated fibrinogen, normal or mildly decreased platelets, and normal or near‐normal aPTT and PT. 58 , 59 , 60 The laboratory testing recommended by major organizations aligns with the reported practice by the survey respondents (Table 4). 28 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 The association of laboratory findings with disease severity also has been identified in several studies. In a single‐center cohort study of 198 patients, an elevated D‐dimer was associated with a 50% increased risk of developing VTE. 22 Moreover, laboratory data may have prognostic value in patients with COVID‐19. 66 Higher levels of D‐dimer have been associated with increased risk of mortality in COVID‐19. 6 , 7 , 67 , 68 In a study of 343 patients, those with a D‐dimer of ≥2.0 μg/mL had a 51.5‐fold increased risk of in‐hospital mortality compared to those with a D‐dimer of <2.0 μg/mL. 69 Our survey findings reflect the ubiquitous monitoring of D‐dimer; 88% of respondents recommend obtaining this test at baseline, and 72% recommend monitoring it three times a week.

TABLE 4.

Recommended laboratory monitoring of hospitalized patients with COVID‐19

| ASH 63 , 70 | ISTH 64 | ACC 28 |

Thrombosis |

SSH 61 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory parameter | |||||

| aPTT | x | x | |||

| ALT | x | ||||

| Creatinine | x | ||||

| D‐dimer | x | x | x | x | |

| Fibrinogen | x | x | x | x | |

| LDH | x | ||||

| Platelets | x | x | x | x | |

| PT/INR | x | x | x | x | |

| DIC transfusion management | |||||

| Nonbleeding patient | Routine blood products not recommended | Maintain: PLT > 25 × 109/L | Maintain: PLT > 20 × 109/L in those with a high bleeding risk or requiring an invasive procedure | Routine blood products not recommended | Not specified |

| Bleeding patient |

Maintain: PLT ≥ 50 × 109/L Fibrinogen ≥ 1.5 g/L INR < 1.8 |

Maintain: PLT > 50 × 109/L Fibrinogen > 1.5 g/L PT Ratio < 1.5 |

Maintain: PLT > 50 × 109/L Fibrinogen ≥ 1.5 g/L aPTT or PT ≤ 1.5 × ULN |

Maintain: PLT > 50 × 109/L Fibrinogen ≥ 1.5 g/L aPTT or PT ≤ 1.5 × ULN TA 1 g IV for patients without DIC rVIIa and PCC are not recommended given they are prothrombotic |

Not specified |

ACC, American College of Cardiology; ALT, alanine transaminase; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; ASH, American Society of Hematology; INR, International normal ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PCC, prothrombin complex concentrate; PLT, platelet count; PT, protime; rVIIa, recombinant activated factor VIIa; SSH, Swedish Society of Hematology; TA, tranexamic acid; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Although rare, COVID‐19 can be associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), usually in the later stages of infection. 4 While the current guidelines provide recommendations for the management of COVID‐19–associated DIC, these recommendations are conflicting. 28 , 29 , 64 , 70 The interim ISTH guidance supports keeping the platelet count >25 × 109/L in patients with DIC even in the absence of bleeding (Table 4). 29 , 64 However, the recently published guidance from ACC and the ASH guidance statement recommend use of blood products only in the setting of DIC‐related bleeding and/or for those in need of invasive procedures or with high risk of bleeding (Table 4) 28 , 70 Although none of the guidelines suggest escalation of anticoagulation in DIC, 12% of the survey participants reported escalating to intermediate‐dose anticoagulation in patients with an elevated DIC score.

Routine testing for APLAs is not recommended in patients with COVID‐19, 6 and only 5% of survey participants reported checking APLAs at baseline. Disease severity and medications used in COVID‐19 can affect lupus anticoagulant testing. Additional coagulation laboratory testing is either not recommended for routine patient management (eg, thromboelastography) 70 or is indicated only in special circumstances. 61 In line with this counsel, <5% of respondents pursue these tests.

Our study provides valuable information to reflect the current practice pattern of a diverse background of clinicians from 41 countries. However, we note a few limitations. Due to the nature of the survey, recall biases of the perceived rates of bleeding or thrombotic complications are likely. Although physicians from 41 countries responded to the survey, there is limited representation from the Asian or African countries. Furthermore, we are unable to provide the percentage of respondents, as we could not collect information on the total number of people who were invited to participate. Our survey was sent via email to multiple international thrombosis groups as well as available on social media. Lastly, studies of COVID‐19 patients are published daily and literature continues to evolve rapidly. Our survey results reflect practice in April 2020 which may change over time.

Identification of current practice patterns about prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of VTE in patients with COVID‐19 has important implications. Our survey highlights consensus including the use of VTE prophylaxis with LMWH or UFH in hospitalized patients. However, there are many unanswered questions, as is reflected in the heterogeneity of current available literature as well as of our survey responses, including the true incidence of VTE in different patient populations with COVID‐19, the use and effects of escalated doses of anticoagulation, and whether extended prophylaxis should be considered and changes outcomes. Well‐conducted epidemiologic studies and clinical trials are urgently needed, and randomized trials addressing these issues are under way.

RELATIONSHIP DISCLOSURE

TZW, SS, KAM, BJH, SRK, BK, and CM declare no conflicts of interest. RPRhas received grants to her institution from BMS and Janssen and consultant/advisory board for BMS, Dova, Janssen, and Portola, all outside the submitted work; KS is a consultant for Pfizer Inc and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; has received grant funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant; and has received travel support from AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals Inc, all outside of the work submitted). SKRajan has received research support from Octapharma, Uniqure, Kedrion, Appelis and consultancy & speakers' honorarium from Alexion, Takeda, Biomarin, Sanofi‐Genzyme, Bayer and Novo Nordisk, all outside the submitted work; FNÁhas received investigator‐initiated grants (paid to university) from Leo Pharma, Actelion, and Bayer, all outside the submitted work; MH has received grants from ZonMW Dutch Healthcare Fund and grants and personal fees from Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Pfizer‐BMS, Bayer Health Care, Aspen, and Daiichi‐Sankyo, outside the submitted work; AYYLee has received honoraria for consultancy for Bayer, BMS, LEO Pharma, Servier, and Pfizer and research support from BMS, all outside the submitted work; LBKis a consultant for the DHHS Vaccine Injury Compensation Program and has received honoraria for participation in advisory boards for CSL Behring and Quercegen Pharmaceuticals, all outside the submitted work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RR and LBK created the concept and design, and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, creation of tables, critical writing and revision of the intellectual content; and final approval. KMS, TFW, SKR, SS, KM contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, writing and revision of the intellectual content; and final approval. FNA, MH, BJH, SRK, BK, AYYL, CM contributed to the design, revision of the intellectual content, and final approval.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society, Venous thromboEmbolism Network United States, Latin American Cooperative Group for Hemostasis and Thrombosis, Unit for Thrombosis and Hemostasis at the Hospital de Clínicas in Uruguay, and the Mexican Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis, the Asia Pacific Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, the Thrombosis and Haemostasis Society of Australia and New Zealand, the Irish Network for VTE Research, and the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis for support of the survey. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1‐TR002494. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr Kahn is a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair holder, and an investigator of the CanVECTOR Network, which receives grant funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Funding Reference: CDT‐142654).

Rosovsky RP, Sanfilippo KM, Wang TF, et al. Anticoagulation practice patterns in COVID-19: A global survey. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4:969–983. 10.1002/rth2.12414

Handling Editor: Dr Cihan Ay

Contributor Information

Rachel P. Rosovsky, Email: rprosovsky@mgh.harvard.edu, @Rosovsky.Rachel.

Kristen M. Sanfilippo, @KSanfilippoMD.

Fionnuala Ní Áinle, @fniainle.

Beverley J. Hunt, @BHWords.

Susan R. Kahn, @SusanRKahn1.

Barry Kevane, @BarryKevane.

Agnes Y. Y. Lee, @AggieLeeMD.

Claire McLintock, @doctormclintock.

Lisa Baumann Kreuziger, @Lbkreuziger.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web‐based dashboard to track COVID‐19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:533–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Al‐Samkari H, Karp Leaf RS, Dzik WH, Carlson JC, Fogerty AE, Waheed A, et al. COVID and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS‐CoV2 infection. Blood. 2020. 10.1182/blood.2020006520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fox SE, Akmatbekov A, Harbert JL, Li G, Brown JQ, Vander Heide RS. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in Covid‐19: the first autopsy series from New Orleans. medRxiv. 2020:2020.04.06.20050575. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luo W, Hong YU, Gou J, Li X, Sun Y, Li J, Liu L. Clinical pathology of critical patient with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID‐19). Preprints (not peer reviewed). Posted 10 April 2020; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1421–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, Schenck EJ, Chen R, Jabri A, et al. Clinical characteristics of Covid‐19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2372–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID‐19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, Parmentier E, Duburcq T, Lassalle F, et al. Pulmonary embolism in COVID‐19 patients: awareness of an increased prevalence. Circulation. 2020;142(2):184–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Artifoni M, Danic G, Gautier G, Gicquel P, Boutoille D, Raffi F, et al. Systematic assessment of venous thromboembolism in COVID‐19 patients receiving thromboprophylaxis: incidence and role of D‐dimer as predictive factors. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50:211–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bompard F, Monnier H, Saab I, Tordjman M, Abdoul H, Fournier L, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with Covid‐19 pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Demelo‐Rodriguez P, Cervilla‐Munoz E, Ordieres‐Ortega L, Parra‐Virto A, Toledano‐Macias M, Toledo‐Samaniego N, et al. Incidence of asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in patients with COVID‐19 pneumonia and elevated D‐dimer levels. Thromb Res. 2020;192:23–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Desborough MJR, Doyle AJ, Griffiths A, Retter A, Breen KA, Hunt BJ. Image‐proven thromboembolism in patients with severe COVID‐19 in a tertiary critical care unit in the United Kingdom. Thromb Res. 2020;193:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fraisse M, Logre E, Pajot O, Mentec H, Plantefeve G, Contou D. Thrombotic and hemorrhagic events in critically ill COVID‐19 patients: a French monocenter retrospective study. Crit Care. 2020;24:275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, Leonard‐Lorant I, Ohana M, Delabranche X, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1089–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Llitjos JF, Leclerc M, Chochois C, Monsallier JM, Ramakers M, Auvray M, et al. High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in anticoagulated severe COVID‐19 patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1743–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, Cecconi M, Ferrazzi P, Sebastian T, et al. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID‐19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Middeldorp S, Coppens M, van Haaps TF, Foppen M, Vlaar AP, Muller MCA, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. 10.1111/jth.14888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nahum J, Morichau‐Beauchant T, Daviaud F, Echegut P, Fichet J, Maillet JM, et al. Venous thrombosis among critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2010478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thomas W, Varley J, Johnston A, Symington E, Robinson M, Sheares K, et al. Thrombotic complications of patients admitted to intensive care with COVID‐19 at a teaching hospital in the United Kingdom. Thromb Res. 2020;191:76–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Voicu S, Bonnin P, Stepanian A, Chousterman BG, Le Gall A, Malissin I, et al. High prevalence of deep vein thrombosis in mechanically ventilated COVID‐19 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang L, Feng X, Zhang D, Jiang C, Mei H, Wang J, et al. Deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in Wuhan, China: prevalence, risk factors, and outcome. Circulation. 2020142(2):114–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Longchamp A, Longchamp J, Manzocchi‐Besson S, Whiting L, Haller C, Jeanneret S, et al. Venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients with Covid‐19: results of a screening study for deep vein thrombosis. Res Pract Thromb Haemostas. 2020;4(5):842–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, Chuich T, Dreyfus I, Driggin E, et al. COVID‐19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow‐up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, Falanga A, Cattaneo M, Levi M, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1023–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhai Z, Li C, Chen Y, Gerotziafas G, Zhang Z, Wan J, et al. Prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism associated with coronavirus disease 2019 infection: a consensus statement before guidelines. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(06):937–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Society BT . BTS Guidance on Venous Thromboembolic Disease in Patients with COVID‐19; 2020. https://www.brit‐thoracic.org.uk/about‐us/covid‐19‐information‐for‐the‐respiratory‐community/ Accessed May 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hunt B, Retter A, McClintock C. Practical Guidance for the Prevention of Thrombosis and Management of Coagulopathy and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation of Patients Infected with COVID‐19. British Society of Hematology; 2020. https://b‐s‐h.org.uk/media/18171/th‐and‐covid‐25‐march‐2020‐final.pdf Accessed March 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hematology ASo . COVID‐19 and VTE/Anticoagulation: Frequently Asked Questions; Version 2.1; 2020. https://www.hematology.org/covid‐19/covid‐19‐and‐vte‐anticoagulation Accessed April 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moores LK, Tritschler T, Brosnahan S, Carrier M, Collen JF, Doerschug K, et al. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID‐19: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2020. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Spyropoulos AC, Levy JH, Ageno W, Connors JM, Hunt BJ, Iba T, et al. Scientific and Standardization Committee Communication: clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. 10.1111/jth.14929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barnes GD, Burnett A, Allen A, Blumenstein M, Clark NP, Cuker A, et al. Thromboembolism and anticoagulant therapy during the COVID‐19 pandemic: interim clinical guidance from the anticoagulation forum. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(1):72–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cannegieter SC, Klok FA. COVID‐19 associated coagulopathy and thromboembolic disease: commentary on an interim expert guidance. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4:439–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cohoon KP, Mahé G, Tafur AJ, Spyropoulos AC. Emergence of institutional antithrombotic protocols for coronavirus 2019. Res Pract Thrombosis Haemostasis. 2020;4(4):510–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alhazzani W, Moller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Crit Care Med. 2020;48(6):e440–e469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Poterucha TJ, Libby P, Goldhaber SZ. More than an anticoagulant: do heparins have direct anti‐inflammatory effects? Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:437–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu J, Li J, Arnold K, Pawlinski R, Key NS. Using heparin molecules to manage COVID‐2019. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4:518–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang TF, Milligan PE, Wong CA, Deal EN, Thoelke MS, Gage BF. Efficacy and safety of high‐dose thromboprophylaxis in morbidly obese inpatients. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:88–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Freeman A, Horner T, Pendleton RC, Rondina MT. Prospective comparison of three enoxaparin dosing regimens to achieve target anti‐factor Xa levels in hospitalized, medically ill patients with extreme obesity. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:740–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Amin AN, Varker H, Princic N, Lin J, Thompson S, Johnston S. Duration of venous thromboembolism risk across a continuum in medically ill hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:231–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cohen AT, Harrington RA, Goldhaber SZ, Hull RD, Wiens BL, Gold A, et al. Extended thromboprophylaxis with betrixaban in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:534–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Spyropoulos AC, Ageno W, Albers GW, Elliott CG, Halperin JL, Hiatt WR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis after hospitalization for medical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1118–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Streiff MB, Holmstrom B, Angelini D, Ashrani A, Bockenstedt PL, Chesney C, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: cancer‐associated venous thromboembolic disease, Version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1289–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carrier M, Abou‐Nassar K, Mallick R, Tagalakis V, Shivakumar S, Schattner A, et al. Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:711–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Khorana AA, Soff GA, Kakkar AK, Vadhan‐Raj S, Riess H, Wun T, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in high‐risk ambulatory patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:720–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Oudkerk M, Buller HR, Kuijpers D, van Es N, Oudkerk SF, McLoud TC, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of thromboembolic complications in COVID‐19: report of the National Institute for Public Health of the Netherlands. Radiology. 2020; 10.1148/radiol.2020201629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Casey K, Iteen A, Nicolini R, Auten J. COVID‐19 pneumonia with hemoptysis: acute segmental pulmonary emboli associated with novel coronavirus infection. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1544.e1–1544.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Obi AT, Barnes GD, Wakefield TW, Brown Rvt S, Eliason JL, Arndt E, et al. Practical diagnosis and treatment of suspected venous thromboembolism during COVID‐19 Pandemic. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(4):526–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID‐19: an updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;19:148–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Aspen Pharmacare Canada Inc . Product Monograph: Fraxiparine®. Fraxiparine‐Product‐Monograph‐ENG‐20190924.pdf. https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00049107.PDF Accessed September 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Maley JH, Petri CR, Brenner LN, Chivukula RR, Calhoun TF, Vinarsky V, et al. Anticoagulation, immortality, and observations of COVID‐19. Res Pract Thrombosis Haemostasis. 2020;4(5):674–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Barco S, Konstantinides SV, Investigators TC‐T. Thrombosis and thromboembolism related to COVID‐19 A clarion call for obtaining solid estimates from large‐scale multicenter data. Res Pract Thrombosis Haemostasis. 2020;4(5):741–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang T, Chen R, Liu C, Liang W, Guan W, Tang R, et al. Attention should be paid to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the management of COVID‐19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e362–e363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lippi G, Plebani M. Laboratory abnormalities in patients with COVID‐2019 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58(7):1131–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Panigada M, Bottino N, Tagliabue P, Grasselli G, Novembrino C, Chantarangkul V, et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID‐19 patients in intensive care unit: a report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J Thrombosis Haemostasis. 2020;18(7):1738–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Spiezia L, Boscolo A, Poletto F, Cerruti L, Tiberio I, Campello E, et al. COVID‐19‐related severe hypercoagulability in patients admitted to intensive care unit for acute respiratory failure. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(06):998–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. La Alessandroa C, Annec A, Pierrea F, Bernhardd G, Lukase G, Ingaf H, et al. Suggestions for thromboprophylaxis and laboratory monitoring for in‐hospital patients with COVID‐19. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020; 10.4414/smw.2020.20247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hematology ASo . COVID‐19 and aPL Antibodies: Frequently Asked Questions; 2020. https://www.hematology.org/covid‐19/covid‐19‐and‐apl‐ab Accessed April 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hematology ASo . COVID‐19 and D‐dimer: Frequently Asked Questions; 2020. https://www.hematology.org/covid‐19/covid‐19‐and‐d‐dimer Accessed April 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, Falanga A, Levi M, Clark C, et al. Laboratory haemostasis monitoring in COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. 10.1111/jth.14866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hunt B, Retter A, McClintock C. Practical Guidance for the Prevention of Thrombosis and Management of Coagulopathy and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation of Patients Infected with COVID‐19; 2020. https://thrombosisuk.org/downloads/T&H%20and%20COVID.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 66. Thachil J, Cushman M, Srivastava A. A proposal for staging COVID‐19 coagulopathy. Res Pract Thrombosis Haemostasis. 2020;4(5):731–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Internal Med. 2020;180(7):934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhang L, Yan X, Fan Q, Liu H, Liu X, Liu Z, et al. D‐dimer levels on admission to predict in‐hospital mortality in patients with Covid‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1324–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hematology ASo . COVID‐19 and Coagulopathy: Frequently Asked Questions; 2020. https://www.hematology.org/covid‐19/covid‐19‐and‐coagulopathy Accessed April 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Anderson DR, Dunbar M, Murnaghan J, Kahn SR, Gross P, Forsythe M, et al. Aspirin or rivaroxaban for VTE prophylaxis after hip or knee arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Weitz JI, Raskob GE, Spyropoulos AC, Spiro TE, De Sanctis Y, Xu J, et al. Thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban in acutely ill medical patients with renal impairment: insights from the MAGELLAN and MARINER trials. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120:515–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1