Abstract

As the architect of racial disparity, racism shapes the vulnerability of communities. Socially vulnerable communities are less resilient in their ability to respond to and recover from natural and human‐made disasters compared with resourced communities. This essay argues that racism exposes practices and structures in public administration that, along with the effects of COVID‐19, have led to disproportionate infection and death rates of Black people. Using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Social Vulnerability Index, the authors analyze the ways Black bodies occupy the most vulnerable communities, making them bear the brunt of COVID‐19's impact. The findings suggest that existing disparities exacerbate COVID‐19 outcomes for Black people. Targeted universalism is offered as an administrative framework to meet the needs of all people impacted by COVID‐19.

COVID‐19 emerged of unknown origin in the last quarter of 2019, first gaining global attention from an outbreak of respiratory illness in Wuhan, China (Hui et al. 2020; Roberts 2020). The virus had reached pandemic levels by March 2020, with countries around the world implementing various forms of public health measures designed to reduce the rate of infection (Adhanom Ghebreyesus 2020). As of this writing, the virus had killed 382,867 people globally and 110,562 people in the United States, infected 6.4 million, and touched everyone (Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center 2020). While much about COVID‐19 remains a mystery, symptomatically, the virus manifests as troubled breathing, a cough, persistent muscle pain or pressure in the chest, and confusion (CDC 2020). The symptoms of COVID‐19 are, in many ways, like the symptoms of American racism—pressure and pain that stifles one's ability to breathe and move freely. Outcomes associated with the daily conditions of Black life in the most vulnerable communities predispose Black people to a host of disparities, health and otherwise (Budoff et al. 2006; Gupta, Carrión‐Carire, and Weiss 2006; Hoberman 2012; Mehta et al. 2006; Wright and Merritt 2020). COVID‐19, for some, further exposes and reiterates, for others, half a millennium of structural racism and repression targeted with administrative precision on the Black body.

As the architect of racial disparity, racism also shapes the vulnerability of communities. Socially vulnerable communities were created through political decisions such as redlining, gentrification, and industrialization and are less resilient in their ability to respond to and recover from natural and human‐made disasters compared with higher‐resourced communities (Pulido 2000). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines social vulnerability as “the resilience of communities when confronted by external stresses on human health, stresses such as natural or human‐caused disasters, or disease outbreaks” (CDC 2018). Socially vulnerable communities (and those living within them) may not be able to respond to COVID‐19 in ways that limit the spread and deathly impact of the virus.

In this essay, we argue that racism exposes structures, policies, and practices that have created social vulnerability. Consequently, these vulnerabilities have interacted with the effects of COVID‐19 in such a way that has led to disproportionate infection and death rates of Black people in the United States. To make this argument, we use the CDC's Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) to analyze the ways in which Black bodies occupy the most vulnerable communities, making them bear the brunt of COVID‐19's impact. Because of high‐level vulnerabilities in many Black communities, the pathogen of racism carries COVID‐19 in such a way that it permeates every aspect of Black life. By using the SVI, we are able to locate the vulnerabilities in a county and examine the relationship between social vulnerability and the Black infection and death rates due to COVID‐19. Ultimately, we seek to understand whether there is a relationship between social vulnerability and the disparate impact of COVID‐19 on Black bodies.

We observe the SVI of two locales—Cuyahoga County, Ohio, and Wayne County, Michigan—along with the death rates of Black people due to COVID‐19 in these counties. We propose the use of targeted universalism as a practice‐oriented framework that achieves universal goals through targeted strategies. Inherently, policy and administrative practices take either a universal approach—guaranteeing a uniform set of rights or benefits for all people, regardless of their social group membership (e.g., the right to vote)—or a targeted approach—policy provisions for specific social groups, generally while excluding others (e.g., the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP). This approach allows the policy discourse to shape implementation and, ultimately, operates to maintain and/or exacerbate inequities (Starke 2020). Conversely, targeted universalism aids policy makers and administrators in responding to COVID‐19 and its disparate effects by developing an outcome‐oriented policy strategy that sets and achieves universal goals through transactional and transformative changes that benefit the most marginalized, thus benefiting the collective (powell, Menendian, and Ake 2019).

Living as the Vulnerable

For some communities across the country, natural disasters, human‐made events, and disease outbreaks have the potential to impose drastic hardships on local infrastructure and individuals living within these communities. Factors such as poverty, poor housing conditions, and inadequate transportation can exacerbate the local impact of emergency events, making some communities more vulnerable to human suffering than others (CDC 2018). Social vulnerability, therefore, refers to the demographic and socioeconomic factors that shape a community's resilience, particularly as it relates to preparing for, responding to, and managing emergency events—natural and otherwise (CDC 2018; Flanagan et al. 2011). Even within communities, the impact of disaster events is inequitable and fall largely along racial and economic lines (Flanagan et al. 2011).

On March 31, 2020, when referring to the coronavirus, New York governor Andrew Cuomo tweeted “this virus is the great equalizer.” 1 Madonna, in an Instagram post that was later deleted, stated, “what's terrible about it is that it's made us all equal in many ways—and what's wonderful about it is that it's made us all equal in many ways.” 2 While perhaps well intentioned, Governor Cuomo's tweet and Madonna's post advance a wider narrative that suggests that everyone, despite their social group membership, has the same potential to be impacted by the virus and in similar ways. However, the “great equalizer” narrative, which has gained some traction in media outlets, runs counter to the historical patterns evident in disasters throughout U.S. history. Emergency management researchers have demonstrated that the impact of emergency events is not random but is, rather, informed “by everyday patterns of social interaction and organization, particularly the resulting stratification paradigms which determine access to resources” (Morrow 1999, 2). Existing inequitable social structures and conditions facilitate vastly different realities for more vulnerable communities and individuals when coping with and being resilient to disaster events. As population characteristics directly impact social vulnerability in contexts of natural and human‐made disasters, it would seem to also hold true with the COVID‐19 pandemic. Perhaps rather than the “great equalizer,” COVID‐19 is “the great revealer” of the persistent inequity that has caused long‐standing social vulnerability (Dahir 2020).

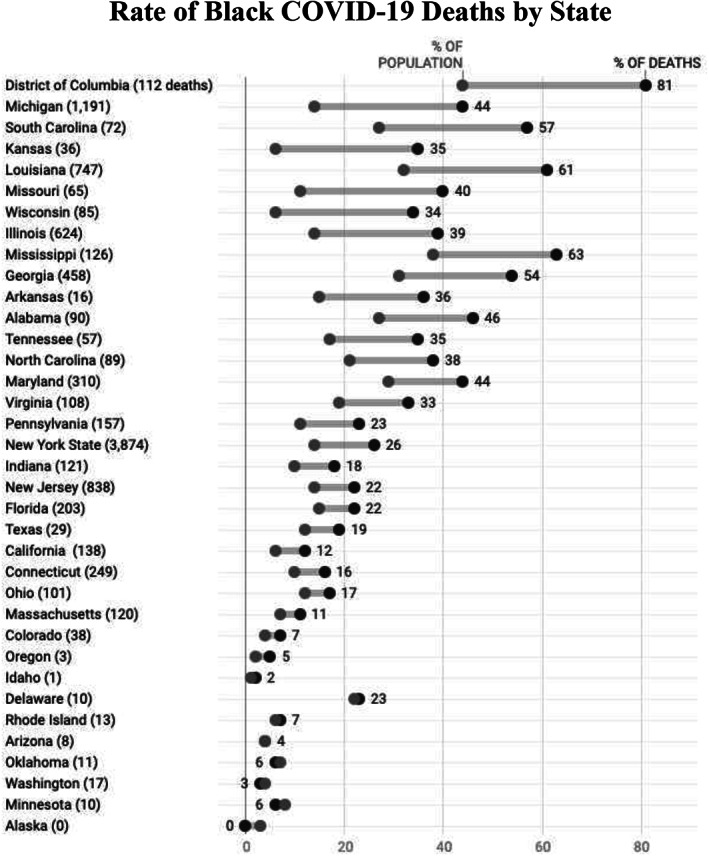

Preliminary data indicate that people of color, primarily Black people, are overwhelmingly and disproportionately affected by the spread of the COVID‐19 virus. In fact, the CDC reported that as of May 15, 2020, 40 percent of national COVID‐19 hospitalizations were non‐Hispanic Black people, compared with 36.5 percent non‐Hispanic White, 14.2 percent Hispanic, and 9.3 percent other (CDC 2020). When comparing these hospitalization rates with population estimates, Black people are, according to these data, hospitalized at a rate almost 3.1 times their population size and the only racial group drastically above their population estimates. Where Black people make up 13.4 percent of the U.S. population, they represent 40 percent of COVID‐19 related hospitalizations (CDC 2020; U.S. Census Bureau n.d.). This disproportionate impact is also evident at the state level. In Illinois, Black people represent 14 percent of the state's population yet 41 percent of those who have died from COVID‐19 (reported as of May 3, 2020) (Illinois Department of Public Health 2020). Black people make up 14 percent of Michigan's population but 40 percent of COVID‐19‐related death cases (APM Research Lab 2020; DeShay 2020; Michigan.gov 2020). As figure 1 highlights, this trend can be seen across the majority of states reporting race‐based COVID‐19 data.

Figure 1.

Rate of Black COVID‐19 Deaths by State.

Note: Total deaths given in parentheses.

Sources: APM Research Lab, data as of April 27, 2020; CDC Social Vulnerability Index.

A community's ability to respond to and recover from a disastrous event rests on social and economic resources. Being able to carry out the recommended practices to “flatten the curve” and slow the spread of COVID‐19 requires individuals and communities access to the privileges that afford such a response. Charles Blow (2020) illustrated in an April 2020 New York Times opinion piece that the privilege of social distancing is not an option for many in the Black community. Black people make up large percentages of the essential workforce and frontline jobs, including workers in grocery and courier delivery, postal service, public and urban transport, and health care (DeShay 2020). Therefore, those who are working are less able to engage in social distancing practices, as for many, social distancing would mean no income (Pedersen and Favero 2020). Further, the Pew Research Center (2020) revealed that Black survey respondents are twice as likely to know someone who has been hospitalized or died from COVID‐19. These disparities underscore the presence of institutional racism in existing public systems (e.g., housing, industrialization, health care, public education, employment patterns, among many others) and the failure of systemic public administration to address the race‐based inequities that left communities vulnerable to heightened COVID‐19 impacts.

Investigating Social Vulnerability and Black Deaths

To explore the relationship between social vulnerability and the disparate impact of COVID‐19, we focus our investigation on Cuyahoga County, Ohio, and Wayne County, Michigan, as each county has the largest Black population in its state. Specifically, we explore the proposition that Black people are more likely to live in communities that are deemed socially vulnerable and, therefore, more likely to be infected by or die from COVID‐19. Our proposition is rooted in a history of social science research that considers that marginally situated people—specifically Black—are left in the most vulnerable communities without necessary resources to mobilize or shift circumstances. These communities have been stripped of its resources and are often in areas where residents are more likely to be exposed to environmental hazards (Mays, Cochran, and Barnes 2007; Wilson 2010). At the intersection of being in highly vulnerable communities, being exposed to environmental injustices, and racism is a perfect storm with Black communities at the center of the COVID‐19 pandemic (Gupta 2020; Taylor 2020). Therefore, we consider the role that racism has played in the creation of socially vulnerable communities and its implications for strengthening equitable public management and emergency relief approaches in local responses to COVID‐19.

Nationally, the response to COVID‐19 has been a patchwork of public officials updating their knowledge base and leveraging resources where possible. In Ohio and Michigan, the governors reacted quickly with stay‐at‐home orders issued to take effect on March 22 and 23, respectively. This universal approach was intended to slow the transmission of the virus; however, it did not consider that businesses deemed essential are occupied by a largely Black labor force. Policy makers, alternatively, could have created an approach that acknowledged that laborers deemed essential were more vulnerable to infection and proceeded accordingly.

In 2007, shortly after the signing of the Pandemic and All‐Hazards Preparedness Act of 2006, the CDC created the Social Vulnerability Index based on U.S. census data from 2000; it is updated with both census and American Community Survey data. The SVI is a database and mapping tool designed to aid public health and disaster management officials in identifying communities with higher vulnerabilities before, during, and after a disaster or emergency crisis (Flanagan et al. 2011). Data used to determine the SVI are based on 15 variables across four individual and community measures: (1) socioeconomic status; (2) household composition and disability; (3) race, ethnicity, and language; and (4) housing and transportation. The SVI produces a score, on a scale from 0 to 1 (lowest to highest vulnerabilities), for each U.S. county and census tract.

Considering the nascency of COVID‐19, data consist of an amalgamation of several sources selected because they are up to date and verifiable. We compared the SVIs of Cuyahoga and Wayne Counties with their respective COVID‐19 confirmed cases and deaths. We recognize there is limited demographic data on COVID‐19, as the CDC, the federal government broadly, and states are not all sharing race‐specific data. Our findings are preliminary and simply show a relationship that requires further investigation when more robust data are made available.

For COVID‐19 data, we use the State of Ohio's COVID‐19 dashboard, the State of Michigan's coronavirus data source, the CDC's Data and Surveillance site, the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, the AWS COVID‐19 Data Lake for hospitalization, and GitHub. We focus on data that use both laboratory‐confirmed cases and presumed cases, as well as a true case fatality rate (CFR). For consistency, we emphasize data that explore testing capacity because the information is integral to producing the most holistic evidence, even as we accept that all data at this time are incomplete.

Other than the clear limitations for epidemiological and public health reasons, we know that no local, county, state, or federal government entity has produced a uniform collection of race data in COVID‐19 reporting (Wolfe 2020). The methods for racial transparency have been ad hoc since the government was called out in early April for its failure to report racial demographics on people impacted by COVID‐19. The government's formal reply was a report that suggested that “black populations might be disproportionately affected by COVID‐19” (Garg 2020). This analysis does not suggest causality but rather trends and trajectories in the available data.

The two counties were selected because they have similar compositions and racial, financial, and industrial histories. Both of these counties have embarked on a re‐creation since the Great Recession, which hit the midwestern region hard, stifling their resilience. Cuyahoga County is in the northeastern part of Ohio and home to Cleveland. The SVI score for Cuyahoga County is 0.6552, indicating moderate to high levels of vulnerabilities. Wayne County is a densely populated area in southeastern Michigan that is known for its ties to the auto industry through Detroit. While it is home to multinational conglomerates, it is also one of Michigan's most vulnerable communities, with a SVI score of 0.8682, marking it as a highly vulnerable community.

Beginning with vulnerability allows us to observe the baseline susceptibility of a community to any disaster; we are then able to adapt that susceptibility to COVID‐19. The SVI considers that vulnerable populations are more disadvantaged in disasters; therefore, it gives more insight into just how vulnerable these populations are when considering the ways COVID‐19 spreads. Densely populated communities are impacted because people have less room to socially distance. SVI indicators are most informative as we consider the transmission of COVID‐19. Seven of these indicators—(1) population over 65, (2) single‐parent households with children under 18, (3) household structures with more than 10 units, (4) more people than rooms, (5) no vehicle available, (6) percent population below poverty, and (7) percent minority population—directly interact with vulnerable populations (e.g., age) to create difficulty in social distancing and shelter‐in‐place orders. Table 1 shows the SVI indicators for the two counties. On the surface, these communities are pretty similar for scales of presumed social vulnerability. Thus, perhaps, both communities are almost equally vulnerable to the virus.

Table 1.

Social Vulnerability Indicators in Cuyahoga County, OH, and Wayne County, MI (percent)

| Cuyahoga County, OH | Wayne County, MI | |

|---|---|---|

| Population over 65 | 17 | 14 |

| Single parent | ||

| Household with children under 18 | 4 | 5 |

| Household structures with more than 10 units | 9 | 5 |

| Household with more people than rooms | 43 | 38 |

| Household with no vehicle | 6 | 5 |

| Population below poverty line | 18 | 23 |

| Minority | 41 | 50 |

Source: CDC Social Vulnerability Index.

These data do not show that either community is more exponentially vulnerable to the virus than the other, but both have vulnerabilities. Wayne County has a higher population of underrepresented people by 10 percent. However, that 10 percent shift does not account for the differential in infections and deaths due to COVID‐19 that separates these communities (see table 2). Wayne County has eight times the number of total infections and 16 times the number of deaths as Cuyahoga County. Both of these communities are vulnerable, but only one, Wayne County, has 2,213 deaths because of COVID‐19, of which 1,255 are in Detroit.

Table 2.

COVID‐19 Data

| Confirmed Cases | Total Deaths | Hospital Bed Utilization (percent) | Black (percent) | Overall CFR (percent) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuyahoga County, OH | 3,321 | 173 | 57 | 5 | |

| Cleveland, OH | 1,046 | 153 | 64 | 15 | |

| Wayne County, MI | 16,729 | 1,782 | 68 | 41 | 11 |

| Detroit, MI | 10,348 | 1,255 | 65 | 12 |

Sources: CDC Case Dashboard; Michigan COVID‐19 Dashboard; Ohio COVID‐19 Dashboard; COVID‐19 Data Lake.

In addition to social vulnerability, we examined the hospitalization rate and hospital capacity in these communities. Hospitalization rate was considered because the CDC indicated that hospital capacity would be the factor that hamstrung the health care system (Devakumar et al. 2020; Garg 2020). Data show that across the United States, Black people are hospitalized at higher rates, in part because of higher rates of COVID‐19 comorbidities (e.g., asthma, heart disease, obesity, etc.). With these other health conditions, if they contract the virus, Black people are more likely to need respiratory therapy (Zephyrin et al. 2020). Both hospital systems are running below capacity and prepared to expand if needed. Cuyahoga is at 55.2 percent intensive care unit (ICU) bed utilization and Wayne is at 67.2 percent ICU bed utilization. The hospitals have not yet reached their capacity, yet more people are dying in Wayne County than in Cuyahoga County. The CFR is higher in Wayne than in Cuyahoga even with widespread testing efforts. Wayne County has a CFR of 10.9 percent, and the Black population has an estimated 12 percent CFR. Table 2 shows rates of infection and percentages of people infected and killed by race. Strikingly, the entire state of Ohio has fewer deaths than Wayne County.

The CFR and rate of infection are vastly underreported because of the lack of free and available testing, which would show asymptomatic cases and shift the denominator on the CFR. Access to testing would have allowed officials to isolate quickly and stop community spread. With these limited data, we are confident in noting preliminary trends that warrant further research, but show promising results that support the proposition. Black people do live in communities that are deemed socially vulnerable; therefore, more likely to contract or die from COVID‐19.

Targeted Universalism for Systemic Change

To restate, the focus of this essay is to examine the relationship between social vulnerability, as measured by the SVI, and the Black infection and death rate due to COVID‐19. Our theoretical mechanisms are rooted in the United States' history of racial bias and social vulnerability.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore (2007, 28) defines racism as “the state‐sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group‐differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” As our findings reveal, socially vulnerable communities, oftentimes communities that are predominantly Black, lack the infrastructure to adequately respond to the impact of COVID‐19 and thus are experiencing disproportionately higher rates of infection and deaths. The relationship between social vulnerability and COVID‐19 outcomes underlines how imperative an equitable public administration is to the well‐being of society at large. Elected officials and career administrators have maintained inequitable systems that operate in such a way that a community's ability to manage a disaster is largely based on its members' access to resources, including economic and racial capital. Communities where redlining occurred, where schools are segregated, and where jobs are scarce are more socially vulnerable. Communities that are economically disadvantaged and have higher concentrations of individuals being discriminated against because of their racial and/or ethnic identity are also more likely to have a higher vulnerability rating.

The legacy of racism and capitalism that has been disproportionately entrenched in Black communities leaves Black people more vulnerable to premature death in the face of COVID‐19. Similar outcomes were present when the levees broke after Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans (Flanagan et al. 2011; Stivers 2007), in Houston after Hurricane Harvey (Bodenreider et al. 2019), and in so many other communities, with many disasters. The difference now seems only to be that this time the disaster is not weather related, but a viral outbreak. Following Gilmore's definition, the social vulnerability allowed to persist in communities across the United States has led to group‐differentiated effects, that in the context of COVID‐19, has prematurely killed Black people at a much higher rate than people of all other ethnic and racial groups.

What can be gleaned, as early lessons, from a better understanding of the trends highlighted? What seems clear is that the maintenance of status quo administration allows for racially disparate outcomes. As long as administrators operate with a business‐as‐usual approach, these racialized disparities will continue. Powell (2020) argues that targeted universalism can be used as a strategy to address the complexities and nuanced nature of the COVID‐19 pandemic, particularly how it impacts different people in different ways. Targeted universalism is a framework to develop inclusive policies and programs that consider the needs of all groups in order to move everyone toward a universal goal. This approach differs from others as it is designed with a focus on inclusion and undermines “active or passive forces of structural exclusion and marginalization, and promotes tangible experiences of belonging. Outgroups are moved from societal neglect to the center of societal care at the same time that more powerful or favored groups' needs are addressed” (powell, Menendian, and Ake 2019, 6). Such an approach requires a range of strategies to facilitate long‐term, transformative impacts.

As states begin to relax stay‐at‐home orders, the possibility of increases in overall infection and death rates looms. This means that Black communities are likely to bear the brunt of the compounded impacts of COVID's initial effects and any subsequent spikes. Targeted universalism allows for a coordinated response that addresses the current and potential future impacts of COVID‐19 for those in resource rich and vulnerable communities. Using a five‐step process, decision makers can work to create and implement their COVID‐19 responses to be targeted, with universal impact (powell, Menendian, and Ake 2019).

The process begins with the identification of a universal goal stemming from a shared societal problem. Currently, local governments across the country are working to slow the spread of COVID‐19 and reduce the number of new cases and related deaths. Second, assessing the overall population performance as it relates to this goal sets a baseline metric for COVID infection and death rates. Having this baseline allows administrators to closely examine the gaps in infection and death rates specific to vulnerable groups. This baseline, while not an overall measure to evaluate the success of an implemented strategy, offers insight into the severity of the problem being addressed.

Having this information makes it easier for administrators to, third, identify populations whose measures are below the baseline metric. Collecting and examining race‐based data—in a uniform, institutionalized, and systemic manner—allows for the identification of existing COVID‐19 inequities as they relate to individuals living in socially vulnerable communities. Data highlighting racial inequity helps administrators, fourth, understand how existing structures advance or limit vulnerable populations from achieving the universal goal. Having a clear understanding of the communities that are more socially vulnerable and the policies and practices that have, over time, allowed these communities to remain and/or grow in this vulnerability enables decisions to be made in such a way that considers and perhaps addresses the structural and systemic barriers that have exacerbated COVID's impact on Black people.

Lastly, the development and implementation of targeted strategies that aid the collective in meeting the universal goal is required. This may include, but is certainly not limited to: extending stay‐at‐home orders allowing frontline workers to remain at home with pay, decreasing their chances of viral exposure; strengthening the quality of health care systems in socially vulnerable communities; and developing equitable and accessible transportation systems that ease one's ability to access quality health care providers.

Preliminary data reveal that Black life is extremely susceptible to the impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic (Deslatte, Hatch, and Stokan 2020). Racism, for Black people, under the conditions of COVID‐19 operates as a comorbidity (Austin 2020). In a just society, race would not shape one's likelihood of dying from a viral pandemic. Underscoring the data is something far greater than differences in infection and death rates. Underlying these data are systems of oppression. What we know about COVID‐19 is that, as a virus, it does not see race, gender, or class, yet it interacts with each of these modifiers in ways that exacerbate the existing oppressive systems that operate to maintain social hierarchy. At a time when New York City is digging mass graves and Michigan communities are scouting ice rinks to store the deceased (Anderson 2020; Dixon 2020; Entress, Tyler, and Sadiq 2020), it feels like a new age, a new day, a new moment. Perhaps the most difficult question is, is the targeting of Black bodies, outside of labor, new in the United States? The novel coronavirus has all but halted the vast majority of the global labor market, but as this essay reveals it is also halting the Black body.

Biographies

Tia Sherèe Gaynor (she/her) is assistant professor in political science and director of the Center for Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation at the University of Cincinnati. Her research focuses on the unjust experiences that individuals at the intersection of race, gender identity, and sexual orientation have when interacting with systemic racism and social hierarchy in public administration.

Email: tiasheree.gaynor@uc.edu

Meghan E. Wilson (she/her) is research associate in political science at Michigan State University. Her research centers public finance, political institutions, and marginally situated people—with a focus on the urban core.

Email: mwilson@msu.edu

Notes

Andrew Cuomo (@NYGovCuomo), “This virus is the great equalizer. Stay strong little brother. You are a sweet, beautiful guy and my best friend. If anyone is #NewYorkTough it's you,” Twitter, March 31, 2020, 12:13 p.m., https://twitter.com/NYGovCuomo/status/1245021319646904320.

Madonna (@madonna), “That's the thing about COVID‐19, It doesn't care about how rich you are, how famous you are, how funny you are, how smart you are, where you live, how old you are, what amazing stories you can tell. It's the great equalizer and what's terrible about it is what's great about it. What's terrible about it is that it's made us all equal in many ways, and what's wonderful about it is that it's made us all equal in many ways. Like I used to say at the end of ‘Human Nature’ every night, if the ship goes down, we're all going down together,” Instagram, March 22, 2020.

References

- Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Tedros . 2020. WHO Director‐General's Opening Remarks at the Mission Briefing on COVID‐19. February 19. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who‐director‐general‐s‐opening‐remarks‐at‐the‐mission‐briefing‐on‐covid‐19 [accessed March 12, 2020].

- Anderson, Meg . 2020. Burials on New York Island Are Not New, but Are Increasing during Pandemic. National Public Radio, April 10. https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus‐live‐updates/2020/04/10/831875297/burials‐on‐new‐york‐island‐are‐not‐new‐but‐are‐increasing‐during‐pandemic [accessed April 10, 2020].

- APM Research Lab . 2020. The Color of Coronavirus: COVID‐19 Deaths by Race and Ethnicity in the U.S. https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths‐by‐race [accessed April 28, 2020].

- Austin, John C . 2020. “COVID‐19 Is Turning the Midwest's Long Legacy of Segregation Deadly.” Brookings. April 30, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the‐avenue/2020/04/17/covid‐19‐is‐turning‐the‐midwests‐long‐legacy‐of‐segregation‐deadly/.

- Blow, Charles M. 2020. Social Distancing Is a Privilege. New York Times, April 5. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/05/opinion/coronavirus‐social‐distancing.html [accessed July 28, 2020].

- Bodenreider, Coline , Wright Lindsey, Barr Omid, Xu Kevin, and Wilson Sacoby. 2019. Assessment of Social, Economic, and Geographic Vulnerability Pre‐ and Post‐Hurricane Harvey in Houston, Texas. Environmental Justice 12(4): 182–93. 10.1089/env.2019.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budoff, Matthew J. , Nasir Khurram, Mao Songshou, Tseng Philip H., Chau Alex, Liu Sandy T., Flores Ferdinand, and Blumenthal Roger S.. 2006. Ethnic Differences of the Presence and Severity of Coronary Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 187(2): 343–50. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . 2018. CDC's Social Vulnerability Index. https://svi.cdc.gov/index.html [accessed September 5, 2018].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . 2020. Symptoms of Coronavirus. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/symptoms‐testing/symptoms.html [accessed April 27, 2020].

- Dahir, Abdi . 2020. Instead of Coronavirus, the Hunger Will Kill Us. A Global Food Crisis Looms. New York Times, April 22, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/world/africa/coronavirus‐hunger‐crisis.html [accessed July 28, 2020 ].

- DeShay, Akiim . 2020. Black COVID‐19 Tracker. https://blackdemographics.com/black‐covid‐19‐tracker/ [accessed May 1, 2020].

- Deslatte, Aaron , Hatch Meghan E., and Stokan Eric. 2020. How Can Local Governments Address Pandemic Inequities? Public Administration Review 80(5): 827–31. 10.1111/puar.13257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devakumar, Delan , Shannon Geordan, Bhopal Sunil S., and Abubakar Ibrahim. 2020. Racism and Discrimination in COVID‐19 Responses. The Lancet 395(10231): 1194. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30792-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, Jennifer . 2020. Oakland County Scouts Ice Rinks to Potentially Store Bodies in “Last Resort” Scenario. Detroit Free Press, April 15. https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/2020/04/15/coronavirus‐oakland‐ice‐rinks‐bodies/5137771002/ [accessed July 28, 2020].

- Entress, Rebecca , Tyler Jenna, and Sadiq Abdul‐Akeem. 2020. Managing Mass Fatalities during COVID‐19: Lessons for Promoting Community Resilience during Global Pandemics. Public Administration Review 80(5): 856–61. 10.1111/puar.13232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, Barry E. , Gregory Edward W., Hallisey Elaine J., Heitgerd Janet L., and Lewis Brian. 2011. A Social Vulnerability Index for Disaster Management. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 8(1): 1–24. 10.2202/1547-7355.1792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garg, Shikha . 2020. Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Laboratory‐Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019—COVID‐NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69(15): 458–64. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, Ruth Wilson . 2007. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Ruchi S. , Carrión‐Carire Violeta, and Weiss Kevin B.. 2006. The Widening Black/White Gap in Asthma Hospitalizations and Mortality. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 117(2): 351–8. 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Sujata . 2020. Why African‐Americans May be Especially Vulnerable to COVID‐19. Science News (blog), April 10. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/coronavirus‐why‐african‐americans‐vulnerable‐covid‐19‐health‐race [accessed July 28, 2020].

- Hoberman, John M. 2012. Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hui, David S. , Azhar Esam I., Madani Tariq A., Ntoumi Francine, Kock Richard, Dar Osman, Ippolito Giuseppe, et al. 2020. The Continuing 2019‐NCoV Epidemic Threat of Novel Coronaviruses to Global Health—The Latest 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 91: 264–6. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Department of Public Health . 2020. COVID‐19 Statistics. https://www.dph.illinois.gov/covid19/covid19‐statistics [accessed May 18, 2020].

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center . 2020. COVID‐19 United States Cases by County. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us‐map [accessed May 17, 2020].

- Mays, Vickie M. , Cochran Susan D., and Barnes Namdi W.. 2007. Race, Race‐Based Discrimination, and Health Outcomes among African Americans. Annual Review of Psychology 58: 201–25. 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, Rajendra H. , Marks David, Califf Robert M., Sohn SeeHyang, Pieper Karen S., Van De Werf Frans, Peterson Eric D., et al. 2006. Differences in the Clinical Features and Outcomes in African Americans and Whites with Myocardial Infarction. American Journal of Medicine 119(1): 70.e1–8. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michigan.gov. 2020. Coronavirus: Michigan Data. https://www.michigan.gov/coronavirus/0,9753,7‐406‐98163_98173—‐,00.html [accessed May 19].

- Morrow, Betty Hearn . 1999. Identifying and Mapping Community Vulnerability. Disasters 23(1): 1–18. 10.1111/1467-7717.00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, Mogens Jin , and Favero Nathan. 2020. Social Distancing during the COVID‐19 Pandemic: Who Are the Present and Future Noncompliers? Public Administration Review 80(5): 805–14. 10.1111/puar.13240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center . 2020. Health Concerns from COVID‐19 Much Higher among Hispanics and Blacks than Whites. April 14. https://www.people‐press.org/2020/04/14/health‐concerns‐from‐covid‐19‐much‐higher‐among‐hispanics‐and‐blacks‐than‐whites/ [accessed July 28, 2020].

- Powell, John A. 2020. Opinion: Coronavirus Is Not the “Great Equalizer” Many Say It Is. East Bay Times, April 16. https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2020/04/16/opinion‐coronavirus‐is‐not‐the‐great‐equalizer‐many‐say‐it‐is/?mc_cid=b9a8355a54&mc_eid=8bf296b3a1 [accessed July 28, 2020].

- Powell, John A. , Menendian Stephen, and Ake Wendy. 2019. Targeted Universalism: Policy & Practice. Haas institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, May. https://www.socalgrantmakers.org/sites/default/files/resources/targeted_universalism_primer.pdf [accessed July 28, 2020].

- Pulido, Laura . 2000. Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90(1): 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Alasdair . 2020. The Third and Fatal Shock: How Pandemic Killed the Millennial Paradigm. Public Administration Review 80(4): 603–9. 10.1111/puar.13223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starke, Anthony M., Jr. 2020. Poverty, Policy, and Federal Administrative Discourse: Are Bureaucrats Speaking Equitable Antipoverty Policy Designs into Existence? Public Administration Review. Published online May 5. 10.1111/puar.13191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stivers, Camilla . 2007. So Poor and So Black: Hurricane Katrina, Public Administration, and the Issue of Race.” Special issue,. Public Administration Review 67: 48–56. 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00812.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Keeanga‐Yamahtta . 2020. The Black Plague. New Yorker, April 16. https://www.newyorker.com/news/our‐columnists/the‐black‐plague [accessed July 28, 2020].

- U.S. Census Bureau . n.d. QuickFacts: United States. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 [accessed May 1, 2020].

- Wolfe, Jan . 2020. “African Americans More Likely to Die from Coronavirus Illness, Early Data Shows.” Reuters. April 30, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us‐health‐coronavirus‐usa‐race‐idUSKBN21O2B6.

- Wright, James, II , and Merritt Cullen. 2020. Social Equity and COVID‐19: The Case of African Americans. Public Administration Review 80(5): 820–26. 10.1111/puar.13251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zephyrin, Laurie . 2020. “COVID‐19 More Prevalent, Deadlier in U.S. Counties with Higher Black Populations,” To the Point (blog), Commonwealth Fund, Apr. 23, 2020. 10.26099/y3xs-qr19. [DOI]