Abstract

Introduction

Due to the COVID‐19 outbreak, all on‐site undergraduate medical teaching activities in Hong Kong have been suspended. A new web‐based surgical skills learning (WSSL) for basic surgical skills training that were normally taught face‐to‐face was developed.

Methodology

Basic surgical skills were taught with normal face‐to‐face tutorial to 30 final year medical students prior to the outbreak. The same group of students were invited to join the online WSSL using Zoom. Evaluation of WSSL was performed by a standardized questionnaire.

Results

Thirty final year medical students (16 female, 14 male students) were recruited into the study. Median age was 23 (range 22‐24). Most of them believed that WSSL is easy to follow. When compared to face‐to‐face teaching. Most students (N = 22, 73.4%) felt that WSSL was just as difficult/easy as conventional teaching for learning instrumental knots. Students were asked to evaluate WSSL by using a Likert scale of 1 to 10 (with 10 being highly recommended). Twelve (40%) students highly recommended WSSL (Score 9 to 10), 15 students (50%) slightly recommended WSSL (Score 6‐8).

Conclusion

Web‐based surgical skills learning is a feasible alternative for face‐to‐face surgical skills teaching.

Keywords: COVID‐19, medical students, Online teaching, surgical teaching

1. INTRODUCTION

An outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) was identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, 1 the virus has quickly spread across the country and resulted in global pandemic across 210 countries with more than 6.8 million cases and nearly 400 000 deaths as reported by 8 June 2020. Most countries have implemented social distancing measures to slow down the spread of infection including closure of schools from primary to tertiary education. 2 Medical education in Hong Kong has also been severely affected, the University of Hong Kong (HKU), one of the two universities (along with The Chinese University of Hong Kong) providing undergraduate medical education in Hong Kong, has implemented a series of social distancing measures during the COVID‐19 outbreak; medical students were no longer allowed to participate in any clinical or on‐site learning activity and had to attend online classes at home.

The undergraduate medical curriculum in HKU is composed of 3‐year pre‐clinical teaching followed by another 3‐year clinical teaching. Basic surgical skills including simple linear incision by using a scalpel and surgical knot tying (instrumental and hand tie) are normally taught face‐to‐face by a general surgeon (Author: MC) in the final year as an interactive tutorial at Queen Mary Hospital, a HKU affiliated hospital. Final year medical students are divided into seven groups with approximately 30 students per group.

This face‐to‐face interactive basic surgical skills tutorial has been implemented for more than 20 years. Each medical student is given a piece of synthetic skin and a suture set (scissors, needle holder, forceps and three packs of suture materials). The suture sets used were bought online, each suture set costs approximately 5 USD, each synthetic skin costs approximately 2 USD. Students are allowed to practice suturing in front of the tutor. The interactive tutorial normally lasts for 120 minutes (including 30 minutes of live demonstration and 90 minutes of hands‐on practice).

Due to the COVID‐19 outbreak, all clinical and face‐to‐face teaching activities in Hong Kong have been suspended. Medical education, including that from the Department of Surgery, in HKU has been severely affected. Lectures were delivered online with video conferencing platform Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, Inc. San Jose, CA, USA), operating theatre attachments were replaced by online surgical demonstration, clinical case studies were replaced by video case sharing, and the basic surgical skills interactive tutorial has also been replaced by online teaching. Here we describe how this online web‐based surgical skills learning (WSSL) is being delivered. This study aims to evaluate the ease of learning from the students' perspective.

2. METHODS

We recruited 30 final year medical students with informed verbal consent into the study. All students have undergone face‐to‐face surgical skills teaching (Surgical tutor: MC) prior to the COVID‐19 outbreak in January. The same group of students was invited to attend WSSL via Zoom on 14 April delivered by the same surgical tutor (MC). The contents of the surgical skills teaching and duration of teaching via WSSL were identical to that delivered face‐to‐face.

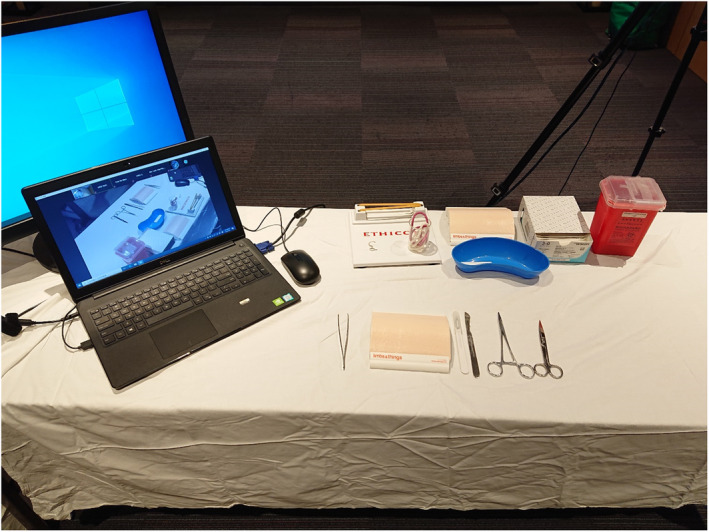

Setup of the computer and camera on the tutor's side is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, instruments used for teaching are shown in Figure 3. Two cameras were used for the live broadcast: Camera One for close‐up capturing tutor's hands for surgical skills demonstration; another built‐in camera (Camera Two) on the computer was used as the usual video conference camera (Figure 3). Camera One is best placed behind the tutor to avoid mirror imaging of the tutor's hand movements.

FIGURE 1.

Setup of the cameras and computers on tutor's side

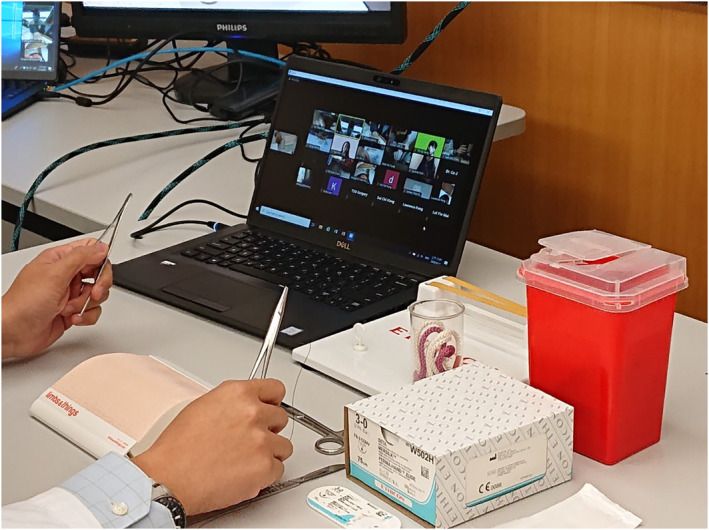

FIGURE 2.

Instruments used in the surgical skills demonstration

FIGURE 3.

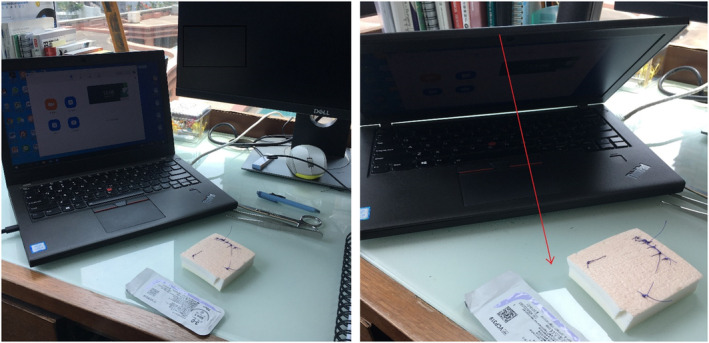

Face‐to‐face tutorial with online platform

Students were instructed to setup their computer at home with camera turned on during WSSL. Camera angle was adjusted to focus on their hands when they were asked to demonstrate the surgical skills (mainly knot tying) to the surgical tutor (Figure 4) and tutor can assess their surgical skills from the monitor (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Setup of the computers and camera at student's home (Arrow illustrating the viewing angle of the camera to focus on student's hands during surgical skills assessment)

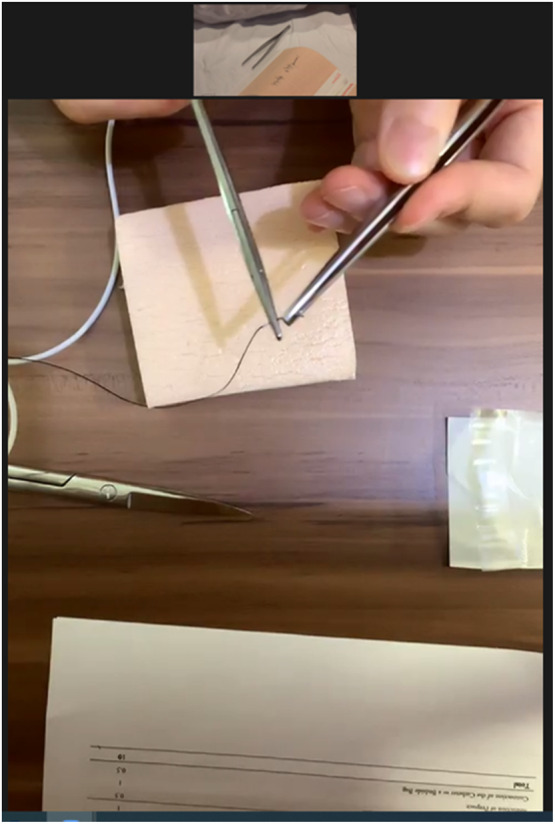

FIGURE 5.

Screen capture illustrating how students' surgical skills can be assessed by the tutor

Immediately after online demonstration of surgical knot tying, students were invited to demonstrate how they perform surgical knots online, one by one. Comments and instructions were given by the surgical tutor (MC).

All students were invited to fill in a standardized questionnaire for feedback after WSSL for objective evaluation of the new teaching program.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline demographics

Thirty students were recruited into the study and responded to the questionnaire. There were 16 female and 14 male students, median age was 23 (Range 22‐24). All students were undergraduate final year medical students and none had other bachelor degree. Twenty‐eight (93.4%) students were right‐handed, one (3.3%) student was left‐handed and one (3.3%) student was ambidextrous. The majority of the students (N = 27, 90%) did not encounter technical issues while installing the necessary hardware or software at home for WSSL. All students were able to participate in WSSL.

3.2. Ease of acquiring basic surgical skills

Students were asked to evaluate the clarity of online demonstration of surgical knot tying using a Likert scale of 1 to 10 (10 being extremely clear and easy to follow). Most of them believed that online demonstration is easy to follow with six (20%) students rated 10/10, eight (26.7%) students rated 9/10, seven (23.3%) students rated 7/10 and eight (26.7%) rated 6/10. Only one (3.3%) student rated 4/10.

Students were also asked to compare demonstration of instrumental surgical knot by WSSL with conventional face‐to‐face teaching. Most students (N = 22, 73.4%) felt that learning of instrumental surgical knot was just as difficult / easy as conventional teaching. Four students (13.3%) felt slightly easier with web‐based teaching and the remaining four (13.3%) students felt slightly more difficult with web‐based learning.

Similarly, students were also asked to compare online demonstration of surgical hand knot with conventional face‐to‐face teaching. More than half of the students (N = 16, 53.3%) felt that WSSL was just as difficult/easy as conventional teaching. Three (10%) students felt that WSSL was slightly easier to follow. Eight (26.7%) students felt slight difficulty with WSSL, while three (10%) students found WSSL much more difficult than conventional face‐to‐face teaching.

3.3. Feedbacks from students

Students were asked to evaluate WSSL by using a Likert scale of 1 to 10, with 9‐10 being highly recommended, 6‐8 being slightly recommended 5 being neutral, 2‐3 being slightly not recommended and 1 being strongly not recommended.

Twelve (40%) students highly recommended the new web‐based surgical teaching format, 15 students (50%) slightly recommended the new web‐based surgical students. Web‐based surgical teaching was slightly unrecommended by three students (10%)

4. DISCUSSION

Acquirement of surgical skill is dependent on both psychomotor and cognitive proficiency, 3 therefore conventional surgical skills demonstration and training relies very much on face‐to‐face teaching where immediate feedback can be given to the learners. Making a secure and proper surgical knot is fundamental in undergraduate surgical training. Students in HKU are normally taught face‐to‐face in the form of a 2‐hour interactive tutorial followed by self‐practice and formal surgical skills assessment.

COVID‐19 started in December 2019 and has resulted in a worldwide pandemic, 1 many countries implementing social distancing policies to contain the viral spread, and undergraduate medical education has also been affected. However, unlike primary or secondary education, delayed graduation from medical schools can result in disastrous outcomes during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 4 , 5 While lectures can be easily delivered online, surgical skills training, which requires a high level of teacher–student interaction, may not be easily demonstrated by pre‐recorded videos. 6 , 7 The Centre for Education and Training at the Department of Surgery, HKU has developed a new web‐based interactive surgical training session to overcome this problem.

This web‐based surgical training has overcome two important obstacles in online surgical training by pre‐recorded videos. Lack of teacher–student interaction and difficulty of learning sophisticated surgical skills due to limited camera viewing angles. Tutors and students were met online and surgical skills were demonstrated live by a second camera zooming and focusing onto the tutor's hands. Camera angle and level of magnification of tutor's hands can be adjusted at any time. Students were allowed to make comments, ask questions during surgical skills demonstration and they were also asked to perform surgical skills tasks in front of the tutor via the same online platform. The same effect cannot be achieved by pre‐recorded video demonstration.

Students involved in this pilot study have undergone both face‐to‐face teaching and the new web‐based training and most of them see this new WSSL as a good replacement to real‐time face‐to‐face surgical skill training during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Only a minority of them experienced initial difficulty in installing the necessary software/hardware for the tutorial. Eventually, all students were able to join the tutorial online without technical difficulty.

Students were each given a set of surgical instruments; this allows immediate demonstration of the newly learnt surgical skills to the tutor during the same WSSL session. However, safety issues of sharps handling must be addressed. Sharp boxes were not distributed to individual student for the disposal of used needles, they were advised not to dispose sharps and needles into their own household rubbish bins. They were advised to collect all used needles, preferably with a small covered plastic box and bring it back to our administrative staff for central disposal of sharps at the end of the surgical rotation.

This web‐based surgical training is affordable, it does not require highly specialized computer programs or professional equipment. We believe online teaching will be the future direction in medical education, even after the COVID outbreak. It is an efficient and convenient way of learning as reflected by the feedback from our students.

With the promising results we have demonstrated in this pilot study, we have formally launched WSSL in the undergraduate surgical curriculum since May 2020. Each 120‐minute WSSL session can accommodate up to 15‐16 students, this allows sufficient time for all students to demonstrate surgical skills in front of the tutor.

We recognize the inherent limitation of this pilot study for the lack of formal performance assessment on students who underwent WSSL. In addition, as all students have already undergone conventional face‐to‐face tutorial prior to WSSL, they should have acquired the surgical skills prior to WSSL and this may affect their perceived difficulty in acquiring the “new” surgical skills. Blinded assessment of student's surgical skills, or preferably in the form of randomized trial, will be needed for evaluation of teaching efficacy of this new teaching method in the future.

In conclusion, WSSL is a feasible alternative to face‐to‐face surgical skills teaching.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Michael Co: Conceptualization, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript.

Kent‐Man Chu: Conceptualization, supervision, final editing.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

All authors report no conflict of interests.

Co M, Chu K‐M. Distant surgical teaching during COVID‐19 ‐ A pilot study on final year medical students. Surg Pract. 2020;24:105–109. 10.1111/1744-1633.12436

Disclaimers

This study is not sponsored by external source of funding.

Full manuscript of this study has never been submitted for publication elsewhere.

REFERENCES

- 1. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. COVID‐19 educational disruption and response. 2020. https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-emergencies/coronavirus-school-closures. Accessed April 12, 2020.

- 3. Treves F. A Manual of Operative Surgery. London, UK: Cassell and Company; 1891. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murphy B. COVID‐19: states call on early medical school grads to bolster workforce. American Medical Association. www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-19-states-call-early-medical-school-grads-bolster-workforce. Accessed April 5, 2020.

- 5. DeWitt DE. Fighting COVID‐19: enabling graduating students to start internship early at their own medical school. Ann Intern Med. 2020;M20‐M1262. [published online ahead of print]. 10.7326/M20-1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gaber DA, Shehata MH, Amin HA. Online team‐based learning sessions as interactive methodologies during the pandemic. Med Educ. 2020;54:666‐667. [published online ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsang ACO, Lee PPW, Chen JY, Leung GKK. From bedside to webside: a neurological clinical teaching experience. Med Educ. 2020;54:660. [published online ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]