Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the associations between prediabetes and the risk of all cause mortality and incident cardiovascular disease in the general population and in patients with a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Design

Updated meta-analysis.

Data sources

Electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar) up to 25 April 2020.

Review methods

Prospective cohort studies or post hoc analysis of clinical trials were included for analysis if they reported adjusted relative risks, odds ratios, or hazard ratios of all cause mortality or cardiovascular disease for prediabetes compared with normoglycaemia. Data were extracted independently by two investigators. Random effects models were used to calculate the relative risks and 95% confidence intervals. The primary outcomes were all cause mortality and composite cardiovascular disease. The secondary outcomes were the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke.

Results

A total of 129 studies were included, involving 10 069 955 individuals for analysis. In the general population, prediabetes was associated with an increased risk of all cause mortality (relative risk 1.13, 95% confidence interval 1.10 to 1.17), composite cardiovascular disease (1.15, 1.11 to 1.18), coronary heart disease (1.16, 1.11 to 1.21), and stroke (1.14, 1.08 to 1.20) in a median follow-up time of 9.8 years. Compared with normoglycaemia, the absolute risk difference in prediabetes for all cause mortality, composite cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke was 7.36 (95% confidence interval 9.59 to 12.51), 8.75 (6.41 to 10.49), 6.59 (4.53 to 8.65), and 3.68 (2.10 to 5.26) per 10 000 person years, respectively. Impaired glucose tolerance carried a higher risk of all cause mortality, coronary heart disease, and stroke than impaired fasting glucose. In patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, prediabetes was associated with an increased risk of all cause mortality (relative risk 1.36, 95% confidence interval 1.21 to 1.54), composite cardiovascular disease (1.37, 1.23 to 1.53), and coronary heart disease (1.15, 1.02 to 1.29) in a median follow-up time of 3.2 years, but no difference was seen for the risk of stroke (1.05, 0.81 to 1.36). Compared with normoglycaemia, in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, the absolute risk difference in prediabetes for all cause mortality, composite cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke was 66.19 (95% confidence interval 38.60 to 99.25), 189.77 (117.97 to 271.84), 40.62 (5.42 to 78.53), and 8.54 (32.43 to 61.45) per 10 000 person years, respectively. No significant heterogeneity was found for the risk of all outcomes seen for the different definitions of prediabetes in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (all P>0.10).

Conclusions

Results indicated that prediabetes was associated with an increased risk of all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease in the general population and in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Screening and appropriate management of prediabetes might contribute to primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Introduction

Prediabetes, also termed intermediate hyperglycaemia or non-diabetic hyperglycaemia, is a high risk metabolic state for diabetes, defined by glycaemic variables that are higher than normal but lower than the thresholds for diabetes.1 2 3 The prevalence of prediabetes is increasing worldwide. Reports estimate that more than 470 million people will have prediabetes by 2030.4 According to an expert panel of the American Diabetes Association, up to 70% of individuals with prediabetes will eventually develop diabetes.5 Our previous meta-analysis, which included 53 prospective cohort studies with more than 1.6 million participants, showed that compared with normoglycaemia, prediabetes was associated with a higher risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality after adjusting for multiple risk factors. The risk was increased even in people with prediabetes defined according to the criteria of the American Diabetes Association, which recommended a cut-off value of 5.6-6.9 mmol/L (100-125 mg/dL) for fasting plasma glucose to define impaired fasting glucose.6 The studies included in the previous meta-analysis were from the general population, so the health risk for prediabetes in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease was not established. In recent years, many studies exploring the associations between prediabetes and the risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality have been published.7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 On their own, most of the studies had limited power to draw solid conclusions, however, and their results have been debated. A recent contentious report in Science defined prediabetes as a “dubious diagnosis” because of the inconsistent association of prediabetes with cardiovascular disease and mortality.15 This opinion reflects the controversy around the term prediabetes, and international consensus is urgently needed.

Given these inconsistencies, we performed an updated meta-analysis to analyse the available data on the prognostic value of prediabetes in individuals with and without baseline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Two key questions were explored: is prediabetes associated with an increased risk of all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease in the general population and in patients with a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; and are different definitions of prediabetes related to different prognoses?

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We performed the search in accordance with the recommendations of the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group.16 Electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar) were searched for studies with a combined MeSH heading and text search strategy, with multiple terms associated with “blood glucose” and “cardiovascular disease” or “mortality.” The first round search was conducted up to 30 June 2019, a second round search was updated on 9 December 2019, and a third round search was updated on 25 April 2020, during the revision process (see supplementary file 1 for the detailed method used to search PubMed). The strategies for the other databases were similar but adapted where necessary. Reference lists were manually checked to identify other potential studies.

Studies were included for analysis if they met these criteria: prospective cohort studies or post hoc analysis of clinical trials of adult individuals (aged ≥18), from the general population or from patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; blood glucose or glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), and other cardiovascular risk factors, were evaluated at baseline; and adjusted relative risks, odds ratios, or hazard ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) were reported for all cause mortality, composite cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke associated with prediabetes in comparison with normoglycaemia.

Prediabetes was defined as any or all of the following: impaired fasting glucose according to the definition of the American Diabetes Association (IFG-ADA)17 or the World Health Organization (IFG-WHO);18 impaired glucose tolerance18; or raised HbA1c according to the criteria of the American Diabetes Association (HbA1c-ADA)17 or the International Expert Committee (HbA1c-IEC).19 Normoglycaemia was defined according to the different guidelines (table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions of normoglycaemia and prediabetes according to different guidelines

| Normal glycaemia | Prediabetes | |

|---|---|---|

| ADA FPG based definition17 | FPG <5.6 mmol/L (<100 mg/dL) | IFG-ADA: FPG 5.6-6.9 mmol/L (100-125 mg/dL) |

| WHO FPG based definition18 | FPG <6.1 mmol/L (<110 mg/dL) | IFG-WHO: FPG 6.1-6.9 mmol/L (110-125 mg/dL) |

| OGTT 2hPG based definition18 | 2hPG <7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL) | IGT: 2hPG 7.8-11.1 mmol/L (140-199 mg/dL) |

| ADA HbA1c based definition17 | HbA1c <39 mmol/mol (5.7%) | HbA1c 39-46 mmol/mol (5.7-6.4%) |

| IEC HbA1c based definition19 | HbA1c <42 mmol/mol (6.0%) | HbA1c 42-46 mmol/mol (6.0-6.4%) |

2hPG=two hour postload plasma glucose; ADA=American Diabetes Association; FPG=fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c= glycated haemoglobin; IGT=impaired glucose tolerance; IEC=International Expert Committee; IFG=impaired fasting glucose; IFG-ADA=impaired fasting glucose according to the definition of the American Diabetes Association; IFG-WHO=impaired fasting glucose according to the definition of the World Health Organization; OGTT=oral glucose tolerance test.

Studies were excluded if: they were retrospective studies or case-control studies; enrolment was not from the general population or from patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; the risk of associated events was unadjusted; and the length of follow-up was less than a year. If multiple articles were derived from the same cohort and reported the same associated outcome, only the latest published report was included for analysis.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators (XC and YZ) independently conducted the literature searches and reviewed the full articles of potentially suitable studies. Quality assessment of the studies was based on the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale for observational studies,20 where a study is judged based on selection (four items, one point each), comparability (one item, up to two points), and exposure/outcome (three items, one point each), up to a maximum score of nine points. The quality of the studies was graded as poor (fewer than four points), fair (four to six points), and good (seven or more points).21 We also evaluated whether the studies had been adequately adjusted for potential confounders, that is, if they included at least five of six risk factors: sex; age; smoking; blood pressure, hypertension, or antihypertensive treatment; body mass index or other measures of overweight or obesity; and hypercholesterolaemia or serum concentrations of cholesterol.22 23

Statistical analysis

Primary outcomes were the risk of all cause mortality and composite cardiovascular events in the general population and in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, respectively. Secondary outcomes were the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in individuals with prediabetes compared with normoglycaemia. Data for outcomes adjusted for the highest number of variables were used for the meta-analysis. We combined the log relative risks or log hazard ratios and corresponding standard errors by the inverse variance approach. Where the odds ratios (ORs) were presented, data were converted to relative risks (RRs) for the meta-analysis (RR=OR/([1−pRef]+[pRef×OR]), where pRef is the prevalence of the outcome in the reference group (normoglycaemia group).24 We used I2 statistics to test for heterogeneity. An I2 value of more than 50% was considered to indicate significant heterogeneity. Even when no statistically significant heterogeneity was seen, however, a random effects model was used as the primary approach to combine results across studies rather than the fixed effects model, owing to underlying methodological heterogeneity (eg, baseline characteristics of the participants, length of follow-up, and adjustment for confounders).

We calculated the absolute risk difference for all cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes associated with prediabetes by multiplying the assumed comparator risk of each outcome of interest by the estimated RR−1, according to the recommendation of the Cochrane guidelines.25 We used the median risks of outcomes in individuals with normoglycaemia across studies as the assumed comparator risks. Absolute risk differences were expressed as events per 10 000 person years.

Subgroup analyses of primary outcomes were conducted according to sex (men v women), ethnicity (Asian v non-Asian), age (average <60 v ≥60), sample size (<5000 v ≥5000 participants), length of follow-up (<10 years v ≥10 years), and study quality (adequate adjustment v inadequate adjustment). We also conducted sensitivity analyses where the use of random effects models was changed to fixed effects models for the meta-analysis or the relative risks were recalculated by omitting one study at a time. Publication bias was evaluated by inspecting funnel plots for the outcomes, and further tested with Begg’s test and Egger’s test.

Meta-regression analysis was used to determine the effect of the definition of prediabetes, ethnicity, sex, participants’ age, length of duration, and number of adjusted confounders on the outcomes if the data were reported in more than 10 studies, according to the Cochrane guidelines.26 The regression coefficient was used to describe how the outcomes changed with the explanatory variable (the potential effect modifier). To assess whether the different ranges of fasting plasma glucose concentrations in impaired fasting glucose had heterogeneity for the prognosis, we reviewed studies with data for prognosis for fasting plasma glucose concentrations of 5.6-6.05 mmol/L (100-109 mg/dL) and 6.1-6.9 mmol/L (110-125 mg/dL), compared with those with fasting plasma glucose concentrations of less than 5.6 mmol/L; the pooled results were then compared for heterogeneity.

Analyses were performed with RevMan 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) and Stata 15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All P values were two tailed, and statistical significance was set at P=0.05.

Patient and public involvement

Most of the authors have been actively involved in the prevention of cardiometabolic disease and maintain strong community links for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. The concerns about the association between health outcomes and prediabetes from the patient and public inspired the author team to perform the study. Because this study was a meta-analysis, patient recruitment or use of patient data was not required. Therefore, we did not involve patients and the public in setting the research question, in the outcome measures, in the design, or the implementation of the study. We also did not ask patients for advice on interpretation or writing up of results. Where possible, the results of this study will be disseminated to the patient community or individual patients through the investigators.

Results

Studies retrieved and characteristics

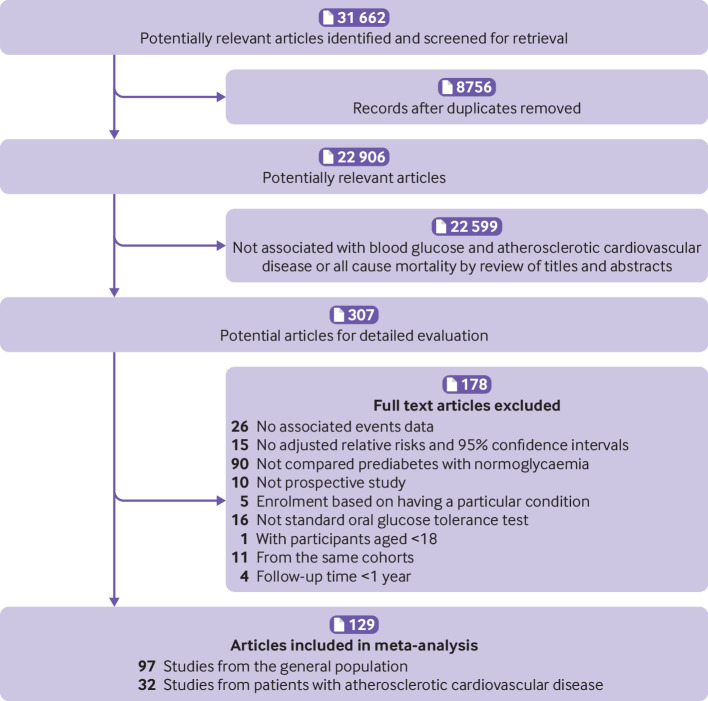

Our initial search returned 31 662 articles. After screening titles and abstracts, 307 articles qualified for a full review (fig 1), and 129 studies, involving 10 069 955 individuals, were included in the analysis. Ninety seven studies (9 972 629 participants with a median follow-up time of 9.8 years, supplementary file 2) and 32 studies (97 326 participants with a median follow-up time of 3.2 years, supplementary file 3) reported an association of prediabetes with the primary outcomes in the general population and in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, respectively.

Fig 1.

Flow of papers through review

The key characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis are presented in supplementary files 4 and 5. Of the 129 studies included, 50 were from Europe, 47 from Asia, 25 from North America (United States and Canada), two from South America (Brazil), three from Oceania (Australia), and one from Africa (Mauritius). One study included patients from Europe and Asia. Based on adjusted confounders, 91 studies (67 from the general population and 24 from patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease) met our criteria for adequate adjustment, while 38 studies (30 from the general population and eight from patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease) did not adequately adjust for potential confounders (supplementary files 6 and 7). According to the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale, 15 studies (11 from the general population and four from patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease) were graded as having fair quality; all other studies were graded as having good quality. Details of the quality assessment are presented in supplementary files 8 and 9.

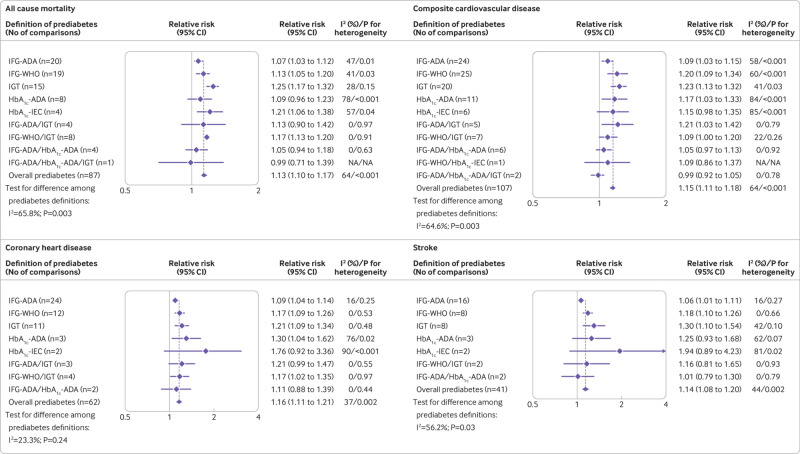

All cause mortality and cardiovascular disease associated with prediabetes in the general population

In the general population, prediabetes was associated with an increased risk of all cause mortality (relative risk 1.13, 95% confidence interval 1.10 to 1.17), composite cardiovascular disease (1.15, 1.11 to 1.18), coronary heart disease (1.16, 1.11 to 1.21), and stroke (1.14, 1.08 to 1.20; fig 2). Significant heterogeneity was seen for the risk of all outcomes (all I2 >50%, P<0.05) except for coronary heart disease (I2=23.3%, P=0.24), for the different definitions of prediabetes.

Fig 2.

Association between prediabetes and the risk of all cause mortality, composite cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke in the general population. HbA1c-ADA=raised glycated haemoglobin according to the definition of the American Diabetes Association; HbA1c-IEC=raised glycated haemoglobin according to the recommendation of the International Expert Committee; IFG-ADA=impaired fasting glucose according to the definition of the American Diabetes Association; IFG-WHO=impaired fasting glucose according to the definition of the World Health Organization; IGT=impaired glucose tolerance

Compared with normoglycaemia, the risk of all cause mortality was significantly increased when prediabetes was defined as IFG-ADA (relative risk 1.07, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.12), IFG-WHO (1.13, 1.05 to 1.20), impaired glucose tolerance (1.25, 1.17 to 1.32), HbA1c-IEC (1.21, 1.06 to 1.38), or combined IFG-WHO and impaired glucose tolerance (1.17, 1.13 to 1.20), but not in studies with other definitions of prediabetes (fig 2). The risk of cardiovascular disease was increased when prediabetes was defined as IFG-ADA (relative risk 1.09, 95% confidence interval 1.03 to 1.15), IFG-WHO (1.20, 1.09 to 1.34), impaired glucose tolerance (1.23, 1.13 to 1.32), HbA1c-ADA (1.17, 1.03 to 1.33), or combined IFG-ADA and impaired glucose tolerance (1.21, 1.03 to 1.42), but not in studies with other definitions of prediabetes (fig 2). Figure 2 also shows the associations of different definitions of prediabetes and the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. The relative risks of all outcomes in individual studies are presented in supplementary files 10-13. We found no evidence of publication bias for all outcomes associated with prediabetes identified by visual inspection of the funnel plot (supplementary file 14) or by Begg’s test and Egger’s test (all P>0.10).

When cardiovascular outcomes or mortality associated with fasting plasma glucose concentrations of 5.6-6.05 mmol/L versus concentrations less than 5.6 mmol/L, or fasting plasma glucose concentrations of 6.1-6.9 mmol/L versus concentrations less than 5.6 mmol/L were reported in the same study, data were pooled to explore whether a step increase in the risk of all cause mortality or composite cardiovascular disease existed in the fasting plasma glucose range in the IFG-ADA definition. Compared with a fasting plasma glucose concentration of less than 5.6 mmol/L, concentrations of 5.6-6.05 mmol/L were associated with only a mildly increased risk of coronary heart disease (relative risk 1.05, 95% confidence interval 1.01 to 1.10) but not with other outcomes. Fasting plasma glucose concentrations of 6.1-6.9 mmol/L were associated with an increased risk of all cause mortality (1.26, 1.16 to 1.36), coronary heart disease (1.12, 1.05 to 1.19), and stroke (1.18, 1.05 to 1.32). Significant heterogeneity was seen for the risk of all cause mortality (I2=92.3%, P<0.001) and stroke (I2=76.5%, P=0.04), but not for composite cardiovascular disease or coronary heart disease, when fasting plasma glucose concentrations of 6.1-6.9 mmol/L were compared with concentrations of 5.6-6.05mmol/L (fig 3).

Fig 3.

Risk of all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease for different ranges of fasting plasma glucose concentrations, based on prediabetes defined as impaired fasting glucose according to the definition of the American Diabetes Association (reference group was fasting plasma glucose concentration <5.6 mmol/L)

The absolute risks of all cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with normoglycaemia across studies from the general population are presented in supplementary file 15. Compared with normoglycaemia, the absolute risk difference in prediabetes for all cause mortality, composite cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke was 7.36 (95% confidence interval 9.59 to 12.51), 8.75 (6.41 to 10.49), 6.59 (4.53 to 8.65), and 3.68 (2.10 to 5.26) per 10 000 person years, respectively. The absolute risk differences for men and women separately are presented in supplementary file 15.

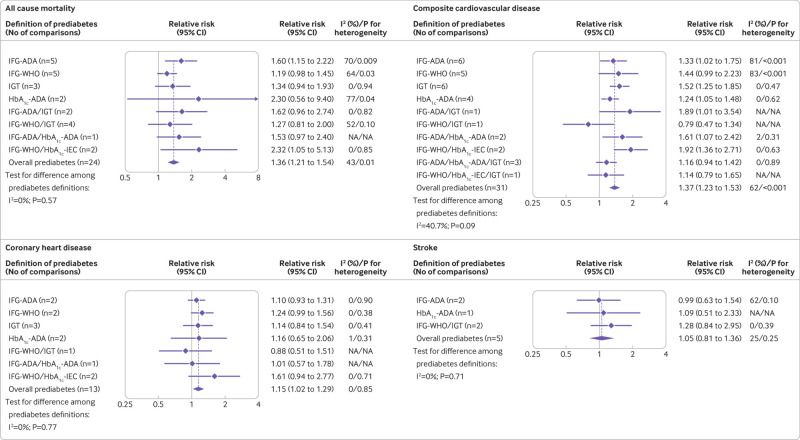

All cause mortality and cardiac outcomes associated with prediabetes in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

In patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, prediabetes was associated with an increased risk of all cause mortality (relative risk 1.36, 95% confidence interval 1.21 to 1.54), composite cardiovascular disease (1.37, 1.23 to 1.53), and coronary heart disease (1.15, 1.02 to 1.29), but no difference was seen for the risk of stroke (1.05, 0.81 to 1.36; fig 4 and supplementary files 16-19). We found no significant heterogeneity for the risk of all outcomes for the different definitions of prediabetes (all I2 <50%, P>0.10). Furthermore, the IFG-ADA definition was associated with an increased risk of all cause mortality (relative risk 1.60, 95% confidence interval 1.15 to 2.22) and composite cardiovascular disease comorbidity (1.33, 1.02 to 1.75) in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. No evidence of publication bias for all outcomes associated with prediabetes was identified by visual inspection of the funnel plot (supplementary file 20) or by Begg’s test and Egger’s test (all P>0.10).

Fig 4.

Association between prediabetes and the risk of all cause mortality, composite cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. HbA1c-ADA=raised glycated haemoglobin according to the definition of the American Diabetes Association; HbA1c-IEC=raised glycated haemoglobin according to the recommendation of the International Expert Committee; IFG-ADA=impaired fasting glucose according to the definition of the American Diabetes Association; IFG-WHO=impaired fasting glucose according to the definition of the World Health Organization; IGT=impaired glucose tolerance

The absolute risks of all cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with normoglycaemia across studies from patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease are presented in supplementary file 21. Compared with normoglycaemia, the absolute risk difference in prediabetes for all cause mortality, composite cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke was 66.19 (95% confidence interval 38.60 to 99.25), 189.77 (117.97 to 271.84), 40.62 (5.42 to 78.53), and 8.54 (−32.43 to 61.45) per 10 000 person years, respectively. We did not report the absolute risk difference associated with men and women separately because of the limited number of studies available.

Subgroup analyses, meta-regression analyses, and sensitivity analyses

The predefined subgroup analyses showed that in the general population, prediabetes was associated with an increased risk of all cause mortality (relative risk range 1.08-1.17), composite cardiovascular disease (1.10-1.22), coronary heart disease (1.09-1.22), and stroke (1.07-1.35) in most subgroup comparisons. We found no significant heterogeneity in most of the subgroup comparisons (table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of the association between prediabetes and outcomes in general population

| Subgroup | All cause mortality | Composite cardiovascular disease | Coronary heart disease | Stroke | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of comparisons | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value* | No of comparisons | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value* | No of comparisons | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value* | No of comparisons | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value* | |||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||

| Asian | 44 | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.19) | 0.96 | 54 | 1.12 (1.07 to 1.17) | 0.29 | 37 | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.12) | 0.01 | 22 | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.17) | 0.23 | ||||

| Non-Asian | 43 | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.18) | 56 | 1.16 (1.11 to 1.22) | 28 | 1.20 (1.12 to 1.29) | 22 | 1.19 (1.08 to 1.33) | ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Men | 30 | 1.13 (1.08 to 1.19) | 0.60 | 33 | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.22) | 0.72 | 23 | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.17) | 0.11 | 12 | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.15) | 0.70 | ||||

| Women | 25 | 1.16 (1.09 to 1.23) | 28 | 1.17 (1.08 to 1.27) | 23 | 1.19 (1.11 to 1.29) | 10 | 1.07 (0.93 to 1.22) | ||||||||

| Participant’s average age | ||||||||||||||||

| <60 | 56 | 1.16 (1.12 to 1.20) | 0.02 | 69 | 1.15 (1.11 to 1.20) | 0.15 | 48 | 1.19 (1.13 to 1.25) | 0.22 | 31 | 1.13 (1.07 to 1.20) | 0.27 | ||||

| ≥60 | 29 | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.14) | 33 | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16) | 13 | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.22) | 13 | 1.23 (1.07 to 1.42) | ||||||||

| Sample | ||||||||||||||||

| <5000 | 34 | 1.15 (1.08 to 1.23) | 0.70 | 45 | 1.22 (1.15 to 1.30) | 0.02 | 33 | 1.16 (1.10 to 1.22) | 0.78 | 23 | 1.23 (1.09 to 1.40) | 0.17 | ||||

| ≥5000 | 53 | 1.13 (1.10 to 1.17) | 65 | 1.12 (1.08 to 1.16) | 32 | 1.17 (1.11 to 1.24) | 21 | 1.12 (1.06 to 1.19) | ||||||||

| Length of follow-up (years) | ||||||||||||||||

| <10 | 52 | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.15) | 0.09 |

59 | 1.10 (1.06 to 1.14) | 0.009 | 28 | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.13) | 0.007 | 16 | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.16) | 0.15 | ||||

| ≥10 | 35 | 1.17 (1.12 to 1.23) | 51 | 1.20 (1.14 to 1.27) | 37 | 1.19 (1.13 to 1.27) | 28 | 1.20 (1.09 to 1.32) | ||||||||

| Possibility of enrolling patients with cardiovascular disease | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 28 | 1.08 (1.04 to 1.13) | 0.03 | 52 | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.19) | 0.88 | 52 | 1.18 (1.12 to 1.24) | 0.03 | 38 | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.22) | 0.99 | ||||

| Might enrolled | 59 | 1.16 (1.12 to 1.20) | 58 | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.21) | 13 | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.15) | 6 | 1.15 (0.92 to 1.45) | ||||||||

| Adjustment of confounders | ||||||||||||||||

| Adequate† | 72 | 1.15 (1.11 to 1.19) | 0.11 | 84 | 1.14 (1.10 to 1.18) | 0.44 | 47 | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.21) | 0.13 |

31 | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.17) | 0.003 | ||||

| Not adequate | 15 | 1.08 (1.00 to 1.17) | 26 | 1.18 (1.09 to 1.27) | 18 | 1.22 (1.15 to 1.30) | 12 | 1.35 (1.20 to 1.51) | ||||||||

For heterogeneity in subgroups.

Adequate adjustment denotes adjustment of at least five of six confounders: sex; age; hypertension, blood pressure, or antihypertensive treatment; body mass index or other measure of overweight or obesity; cholesterol; and smoking.

In patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, the risk of all cause mortality associated with prediabetes was higher in Asian (relative risk 1.66, 95% confidence interval 1.37 to 2.01) than in non-Asian patients (1.22, 1.07 to 1.40; P=0.01 for heterogeneity). The risk of composite cardiovascular disease was higher in women with prediabetes (2.26, 1.27 to 4.04) than in men with prediabetes (1.16, 0.54 to 2.47; P=0.02 for heterogeneity). No significant heterogeneity was seen in the other subgroup comparisons for all outcomes (all P>0.05; table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses of association between prediabetes and outcomes in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

| Subgroup | All cause mortality | Composite cardiovascular disease | Coronary heart disease | Stroke | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of comparisons | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value* | No of comparisons | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value* | No of comparisons | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value* | No of comparisons | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value* | |||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||

| Asian | 9 | 1.66 (1.37 to 2.01) | 0.01 | 11 | 1.42 (1.21 to 1.67) | 0.47 | 4 | 1.35 (1.08 to 1.70) | 0.14 | 2 | 1.12 (0.74 to 1.70) | 0.97 | ||||

| Non-Asian | 15 | 1.22 (1.07 to 1.40) | 20 | 1.32 (1.14 to 1.51) | 9 | 1.11 (0.97 to 1.27) | 3 | 1.11 (0.71 to 1.71) | ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Men | 1 | 1.57 (0.83 to 2.95) | 0.93 | 2 | 1.16 (0.54 to 2.47) | 0.02 | NA | — | — |

NA | — | — | ||||

| Women | 1 | 1.68 (0.45 to 6.29) | 2 | 2.26 (1.27 to 4.04) | NA | — | NA | — | ||||||||

| Participant’s average age | ||||||||||||||||

| <60 | 5 | 1.32 (1.16 to 1.49) | 0.44 | 9 | 1.29 (1.08 to 1.54) | 0.43 | 4 | 1.22 (1.02 to 1.47) | 0.42 | 3 | 1.03 (0.71 to 1.50) | 0.52 | ||||

| ≥60 | 19 | 1.44 (1.19 to 1.73) | 22 | 1.42 (1.22 to 1.65) | 9 | 1.16 (1.00 to 1.36) | 2 | 1.24 (0.81 to 1.88) | ||||||||

| Sample | ||||||||||||||||

| <5000 | 20 | 1.50 (1.26 to 1.78) | 0.11 | 26 | 1.40 (1.21 to 1.61) | 0.19 | 10 | 1.11 (0.97 to 1.26) | 0.08 | 4 | 1.08 (0.79 to 1.47) | 0.99 | ||||

| ≥5000 | 4 | 1.24 (1.05 to 1.45) | 5 | 1.24 (1.12 to 1.38) | 3 | 1.38 (1.12 to 1.71) | 1 | 1.09 (0.51 to 2.33) | ||||||||

| Length of follow-up (years) | ||||||||||||||||

| <10 | 21 | 1.44 (1.25 to 1.66) | 0.04 | 29 | 1.40 (1.24 to 1.58) | 0.21 | 13 | 1.15 (1.02 to 1.29) | — | 5 | 1.05 (0.81 to 1.36) | — | ||||

| ≥10 | 2 | 1.20 (1.08 to 1.33) | 2 | 1.07 (0.71 to 1.60) | NA | — | NA | — | ||||||||

| Adjustment of confounders | ||||||||||||||||

| Adequate† | 17 | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.59) | 0.64 | 22 | 1.27 (1.15 to 1.41) | 0.21 | 8 | 1.20 (1.06 to 1.36) | 0.45 | 4 | 0.97 (0.78 to 1.23) | 0.18 | ||||

| Not adequate | 7 | 1.28 (0.90 to 1.81) | 9 | 1.61 (1.12 to 2.32) | 5 | 1.07 (0.82 to 1.40) | 1 | 1.71 (0.77 to 3.78) | ||||||||

NA=not applicable.

For heterogeneity in subgroups.

Adequate adjustment denoted adjustment of at least five of six confounders: sex; age; hypertension, blood pressure, or antihypertensive treatment; body mass index or other measure of overweight or obesity; cholesterol; and smoking.

Meta-regression analysis showed that in the general population, impaired glucose tolerance carried a higher risk of all cause mortality (P=0.002) and stroke (P=0.043) compared with impaired fasting glucose. The prediabetes IFG-WHO definition also had a higher risk of stroke than the IFG-ADA definition (P=0.02, supplementary file 22). In patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, the risk of all cause mortality associated with prediabetes was also higher in Asian than in non-Asian patients (P=0.03), as reported in the subgroup analysis. No other significant associations in study characteristics and risk of endpoint events were seen (all P>0.10, supplementary file 23).

The sensitivity analyses confirmed that the association between prediabetes and risk of endpoint events did not change with the use of random effects models or fixed effects models for the meta-analysis, or with recalculation of the relative risks by omitting one study at a time.

Discussion

Principal findings

In this comprehensive meta-analysis with 129 studies involving more than 10 million participants, three major findings emerged. Firstly, compared with normoglycaemia, prediabetes was associated with an increased risk of all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease in the general population and in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Secondly, in the general population, impaired glucose tolerance carried a higher risk of all cause mortality, coronary heart disease, and stroke than impaired fasting glucose. Thirdly, the risk of all cause mortality associated with impaired fasting glucose was mainly attributed to fasting plasma glucose concentrations in the range 6.1-6.9 mmol/L.

Comparison with previous studies

According to the current definition of the American Diabetes Association, the prevalence of prediabetes in adults is up to 36.2% in the United States27 and 35.7% in China.28 Despite discrepancies in definitions, the prevalence of prediabetes is clearly rising. The term prediabetes, however, has been much debated. One view is that recognition of this condition could help to boost efforts to reduce the future burden of diabetes and its complications.4 29 The counterargument is that describing people with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes as having prediabetes creates more problems than benefits in terms of prevention and treatment, resulting in unnecessary medical intervention and an unsustainable burden on healthcare systems.15 30 In 2016, our group reported that prediabetes, defined as impaired fasting glucose according to the definition of the American Diabetes Association or the World Health Organization, or impaired glucose tolerance, was associated with increased all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease in the general population.6 In this study, we updated our data and further supported our previous research, which showed that the risk of all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease was increased in people with prediabetes, even when defined according to the lower cut-off point of impaired fasting glucose proposed by the current definition of the American Diabetes Association.

Furthermore, our study showed new findings. Firstly, significant heterogeneity was found for the risk of all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease for different definitions of prediabetes in the general population. Individuals with impaired glucose tolerance were susceptible to a higher risk of all cause mortality than those with impaired fasting glucose. The increased risk was seen even when fasting plasma glucose concentrations were as low as 5.6-6.9 mmol/L, supported by a meta-analysis of individual participant data performed by the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, which showed that fasting plasma glucose concentrations exceeding 5.6 mmol/L were associated with increased mortality.31 We also found that the risk was mainly driven by fasting plasma glucose concentrations in the range 6.1-6.9 mmol/L. These results are important for future selection of those at high risk for prevention trials. Secondly, the inclusion of HbA1c as a criterion for diabetes and prediabetes has led to concerns of its limited use for predicting future cardiovascular disease events.32 In this study, we found that the risk of composite cardiovascular events and coronary heart disease was increased in the general population with a HbA1c concentration of 39-47 mmol/mol (5.7-6.4%). These results provide evidence for the inclusion of HbA1c in defining prediabetes. HbA1c is an easier method for screening than the oral glucose tolerance test, which is time consuming. Hence this information would help stratification to prioritise a screening programme. Thirdly, we found that prediabetes was also associated with an increased risk of mortality and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. These results suggest that managing prediabetes in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease might also be an important goal to lower their future risk of recurrent cardiovascular disease and premature death.

Implications of the study and future research

Considering the high prevalence of prediabetes, and the robust and significant association between prediabetes and health risk shown in our study, successful intervention in this large population could have a major effect on public health. Although prediabetes is commonly asymptomatic, it represents a window of opportunity to prevent progression to type 2 diabetes and its complications.33 Community mobilisation and lifestyle intervention for prediabetes can lead to a significant reduction in the incidence of diabetes.29 34 Follow-up studies from the Diabetes Prevention Programme have shown that lifestyle intervention can be cost effective in preventing diabetes, and that treatment with metformin can even be cost saving.35 The Let’s Prevent Diabetes cluster randomised controlled trial showed that a relatively low resource, a pragmatic diabetes prevention programme, had modest benefits for biomedical, lifestyle, and psychosocial outcomes.36 Two systematic reviews and network meta-analyses also reported that lifestyle intervention in prediabetes is beneficial in reducing the risk of progression to type 2 diabetes.37 38 Furthermore, the 30 year results of the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome Study showed that lifestyle intervention in people with impaired glucose tolerance reduced the incidence of cardiovascular events and all cause mortality, providing strong justification for intervention for prediabetes.39

Similarly, the NAVIGATOR (long term study of nateglinide and valsartan to prevent or delay type II diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular complications) trial showed that in individuals at high risk of cardiovascular disease with impaired glucose tolerance, baseline levels of daily ambulatory activity and change in ambulatory activity showed a graded inverse association with the subsequent risk of a cardiovascular event.40 Based on these results, guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology on diabetes, prediabetes, and cardiovascular disease recommended lifestyle changes as a key prevention aspect of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.41 Data on prevention of cardiovascular disease in people with impaired fasting glucose or raised HbA1c concentrations are lacking. However, whether results from trials with impaired glucose tolerance will apply to individuals with other definitions of prediabetes is questionable. Thus intervention studies in prediabetes identified by fasting plasma glucose or HbA1c concentrations are warranted.

In patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, the risk of all cause mortality associated with prediabetes was higher in Asian than in non-Asian patients. Although a chance finding cannot be excluded, previous studies have suggested plausible and interesting mechanisms. Firstly, compared with their Western counterparts, Asian individuals might have a different pattern for complications of diabetes.42 A meta-analysis of interventional randomised controlled trials showed that the risk of microvascular events and new or worsening nephropathy was significantly higher in Asian patients than in western patients.43 In our analysis, the risk of macrovascular disease (composite cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke) associated with prediabetes was similar in Asian and non-Asian patients. Therefore, the increased risk of all cause mortality might be attributed to microvascular events. This finding is further supported by previous studies which showed that Asian patients with prediabetes might progress more rapidly to clinical diabetes,44 and when they develop diabetes, microvascular complications develop more rapidly.45

Secondly, differences in genetics, socioeconomic factors, and treatment approaches for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease between Asia and other continents might also have a role in the influence of prediabetes on mortality in Asia.43 46 Based on these results, prediabetes management programmes, tailored to Asian patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, might be clinically important, and these programmes should be investigated in future studies. Thirdly, in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, there might be a survival advantage associated with overweight or obesity (so-called obesity paradox).47 48 Phenotypic differences in people with impaired glucose regulation have been seen between ethnic groups. Asian populations develop impaired glucose regulation at lower levels of body mass index than European populations,49 and therefore they might not experience the obesity paradox similarly to their Western counterparts.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Our study has several strengths. Firstly, only prospective cohort studies or post hoc analysis of clinical trials with adjusted relative risks were included. Most of the studies included in the analysis were of high quality and adequately adjusted for confounders. This might mitigate the possibility of other cardiovascular risk factors influencing the association of prediabetes with the health risk observed. Secondly, the number of available studies and the sample size were large, which allowed us to perform multiple subgroup analyses and meta-regression analysis to explore the association in different definitions of prediabetes and the risk of mortality and cardiovascular disease. Similar risk across subgroups according to age, sex, and length of follow-up further strengthens our conclusion.

Some limitations of the study should be noted. Firstly, we had no access to individual participants’ data and potential confounders could not be ruled out. Secondly, it is unclear whether the increased risk seen in our study was a result of prediabetes or the transition from prediabetes to diabetes during follow-up. Several studies have provided evidence that the increased risk associated with prediabetes is not, however, dependent on progression to diabetes. A Finnish study showed that an increased risk of cardiovascular disease associated with impaired glucose tolerance remained significant after excluding patients with impaired glucose tolerance who subsequently developed overt diabetes during follow-up analyses.50 Similarly, a nested case-control study from Japan showed that persistent prediabetes, defined by fasting plasma glucose concentrations of 5.6-6.9 mmol/L or HbA1c 39-47 mmol/mol (5.7-6.4%), was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, in people with prediabetes before progression to overt diabetes, inverse linear associations were found between measures of glycaemia (HbA1c, fasting, and two hour postload glucose concentrations) and microvascular function, independent of cardiovascular risk factors.51 Thirdly, in most of the included studies, people with low blood glucose concentrations were not excluded. Some studies have shown that the association of fasting plasma glucose concentrations with cardiovascular disease has a J shaped curve.52 53 54 The inclusion of people with low blood glucose concentrations in the reference group would make the association of prediabetes and risk towards null. Fourthly, we did not find that the risk of stroke was associated with prediabetes in patients with baseline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Most of the studies included patients with coronary heart disease, however, only one study included patients based on previous stroke. Therefore, whether prediabetes is associated with the recurrent risk of stroke is still unclear.

Conclusions

Prediabetes was associated with an increased risk of all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease in the general population and in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Screening and proper management of prediabetes might contribute to primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

What is already known on this topic

Prediabetes is a common condition worldwide with a high prevalence

A previous meta-analysis showed that prediabetes was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events in the general population, although this finding was controversial

Reports on the association of prediabetes with prognosis in patients with a history of cardiovascular disease are inconsistent

What this study adds

Prediabetes was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality

Different definitions of prediabetes were associated with a similar prognosis in patients with a history of cardiovascular disease

Screening and proper management of prediabetes might contribute to primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Supplementary material

Contributors: XC, YHu, and YHuang were responsible for the initial plan, study design, conducting the study, and data interpretation. XC, YZ, ML, LM, and YHuang were responsible for data collection, data extraction, statistical analysis, and manuscript drafting. YZ, JHYW, YHu, JL, YY, and YHuang analysed and interpreted the data, and critically revised the paper. XC and YHuang are guarantors and had full access to all of the data, including statistical reports and tables, and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This project was supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Fund (key project of Guangdong-Foshan Joint Fund, 2019B1515120044), Science and Technology Innovation Project from Foshan, Guangdong (FS0AA-KJ218-1301-0006), and the Clinical Research Startup Programme of Shunde Hospital, Southern Medical University (CRSP2019001). The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: support from the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Fund, Science and Technology Innovation Project, and Clinical Research Startup Programme of Shunde Hospital, Southern Medical University for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: Additional data available from the corresponding author at hyuli821@smu.edu.cn.

The lead author (YHuang) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: The results from the study will be disseminated to appropriate audiences such as academia, clinicians, policy makers, and the general public through various channels, including press release, social media, e-newsletter, websites of collaborators’ universities, and monthly bulletins.

References

- 1. Vas PRJ, Alberti KG, Edmonds ME. Prediabetes: moving away from a glucocentric definition. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:848-9. 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30234-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tabák AG, Herder C, Rathmann W, Brunner EJ, Kivimäki M. Prediabetes: a high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet 2012;379:2279-90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60283-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beulens J, Rutters F, Rydén L, et al. Risk and management of pre-diabetes. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019;26(2_suppl):47-54. 10.1177/2047487319880041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Makaroff LE. The need for international consensus on prediabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:5-7. 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30328-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Diabetes Association 3. Prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 2020;43(Suppl 1):S32-6. 10.2337/dc20-S003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huang Y, Cai X, Mai W, Li M, Hu Y. Association between prediabetes and risk of cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016;355:i5953. 10.1136/bmj.i5953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang T, Lu J, Su Q, et al. 4C Study Group Ideal cardiovascular health metrics and major cardiovascular events in patients with prediabetes and diabetes. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:874-83. 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.2499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lu J, He J, Li M, et al. 4C Study Group Predictive value of fasting glucose, postload glucose, and hemoglobin A1c on risk of diabetes and complications in Chinese adults. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1539-48. 10.2337/dc18-1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hubbard D, Colantonio LD, Tanner RM, et al. Prediabetes and risk for cardiovascular disease by hypertension status in black adults: the Jackson heart study. Diabetes Care 2019;42:2322-9. 10.2337/dc19-1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tang O, Matsushita K, Coresh J, et al. Mortality implications of prediabetes and diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care 2020;43:382-8. 10.2337/dc19-1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Welsh C, Welsh P, Celis-Morales CA, et al. Glycated hemoglobin, prediabetes, and the links to cardiovascular disease: data from UK Biobank. Diabetes Care 2020;43:440-5. 10.2337/dc19-1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vistisen D, Witte DR, Brunner EJ, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease and death in individuals with prediabetes defined by different criteria: the Whitehall II study. Diabetes Care 2018;41:899-906. 10.2337/dc17-2530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim NH, Kwon TY, Yu S, et al. Increased vascular disease mortality risk in prediabetic Korean adults is mainly attributable to ischemic stroke. Stroke 2017;48:840-5. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Warren B, Pankow JS, Matsushita K, et al. Comparative prognostic performance of definitions of prediabetes: a prospective cohort analysis of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:34-42. 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30321-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Piller C. Dubious diagnosis. Science 2019;363:1026-31. 10.1126/science.363.6431.1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008-12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2003;26(Suppl 1):S5-20. 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.S5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization Consultation. Definition and diagnosis of diabetes and intermediate hyperglycaemia. 2006. https://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/Definition%20and%20diagnosis%20of%20diabetes_new.pdf.

- 19. International Expert Committee International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1327-34. 10.2337/dc09-9033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 21. Li M, Huang JT, Tan Y, Yang BP, Tang ZY. Shift work and risk of stroke: A meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2016;214:370-3. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.03.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, et al. Methods Work Group, Third US Preventive Services Task Force Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med 2001;20(Suppl):21-35. 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00261-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang Y, Huang W, Mai W, et al. White-coat hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and total mortality. J Hypertens 2017;35:677-88. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA 1998;280:1690-1. 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schünemann HJ, Higgins JPT, Vist GE, et al. Chapter 14: Completing ‘Summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0. Cochrane, 2019. https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- 26.Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0. Cochrane, 2019. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- 27. Bullard KM, Saydah SH, Imperatore G, et al. Secular changes in US prediabetes prevalence defined by hemoglobin A1c and fasting plasma glucose: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1999-2010. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2286-93. 10.2337/dc12-2563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang L, Gao P, Zhang M, et al. Prevalence and ethnic pattern of diabetes and prediabetes in China in 2013. JAMA 2017;317:2515-23. 10.1001/jama.2017.7596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cefalu WT, Petersen MP, Ratner RE. The alarming and rising costs of diabetes and prediabetes: a call for action! Diabetes Care 2014;37:3137-8. 10.2337/dc14-2329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nguyen BM, Lin KW, Mishori R. Public health implications of overscreening for carotid artery stenosis, prediabetes, and thyroid cancer. Public Health Rev 2018;39:18. 10.1186/s40985-018-0095-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rao Kondapally Seshasai S, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, et al. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med 2011;364:829-41. 10.1056/NEJMoa1008862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vajravelu ME, Lee JM. Identifying prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in asymptomatic youth: should HbA1c be used as a diagnostic approach? Curr Diab Rep 2018;18:43. 10.1007/s11892-018-1012-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mangan A, Docherty NG, Le Roux CW, Al-Najim W. Current and emerging pharmacotherapy for prediabetes: are we moving forward? Expert Opin Pharmacother 2018;19:1663-73. 10.1080/14656566.2018.1517155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fottrell E, Ahmed N, Morrison J, et al. Community groups or mobile phone messaging to prevent and control type 2 diabetes and intermediate hyperglycaemia in Bangladesh (DMagic): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;7:200-12. 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30001-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carris NW, Cheng F, Kelly WN. The changing cost to prevent diabetes: A retrospective analysis of the Diabetes Prevention Program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2017;57:717-22. 10.1016/j.japh.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Davies MJ, Gray LJ, Troughton J, et al. Let’s Prevent Diabetes Team A community based primary prevention programme for type 2 diabetes integrating identification and lifestyle intervention for prevention: the Let’s Prevent Diabetes cluster randomised controlled trial. Prev Med 2016;84:48-56. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stevens JW, Khunti K, Harvey R, et al. Preventing the progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults at high risk: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of lifestyle, pharmacological and surgical interventions. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015;107:320-31. 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yamaoka K, Nemoto A, Tango T. Comparison of the effectiveness of lifestyle modification with other treatments on the incidence of type 2 diabetes in people at high risk: a network meta-analysis. Nutrients 2019;11:E1373. 10.3390/nu11061373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gong Q, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study Group Morbidity and mortality after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance: 30-year results of the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;7:452-61. 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30093-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yates T, Haffner SM, Schulte PJ, et al. Association between change in daily ambulatory activity and cardiovascular events in people with impaired glucose tolerance (NAVIGATOR trial): a cohort analysis. Lancet 2014;383:1059-66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62061-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J 2020;41:255-323. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang JJ, Yu D, Wen W, et al. Association of diabetes with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Asia: a pooled analysis of more than 1 million participants. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e192696. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li J, Dong Y, Wu T, Tong N. Differences between Western and Asian type 2 diabetes patients in the incidence of vascular complications and mortality: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials on lowering blood glucose. J Diabetes 2016;8:824-33. 10.1111/1753-0407.12361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Admiraal WM, Holleman F, Snijder MB, et al. Ethnic disparities in the association of impaired fasting glucose with the 10-year cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;103:127-32. 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gupta R, Misra A. Epidemiology of microvascular complications of diabetes in South Asians and comparison with other ethnicities. J Diabetes 2016;8:470-82. 10.1111/1753-0407.12378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Spanakis EK, Golden SH. Race/ethnic difference in diabetes and diabetic complications. Curr Diab Rep 2013;13:814-23. 10.1007/s11892-013-0421-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Uretsky S, Messerli FH, Bangalore S, et al. Obesity paradox in patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease. Am J Med 2007;120:863-70. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pagidipati NJ, Zheng Y, Green JB, et al. TECOS Study Group Association of obesity with cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: Insights from TECOS. Am Heart J 2020;219:47-57. 10.1016/j.ahj.2019.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hare MJ, Shaw JE. Ethnicity considerations in diagnosing glucose disorders. Curr Diabetes Rev 2016;12:51-7. 10.2174/1573399811666150211112455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Qiao Q, Jousilahti P, Eriksson J, Tuomilehto J. Predictive properties of impaired glucose tolerance for cardiovascular risk are not explained by the development of overt diabetes during follow-up. Diabetes Care 2003;26:2910-4. 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sörensen BM, Houben AJ, Berendschot TT, et al. Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes are associated with generalized microvascular dysfunction: the Maastricht study. Circulation 2016;134:1339-52. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Palta P, Huang ES, Kalyani RR, Golden SH, Yeh HC. Hemoglobin A1c and mortality in older adults with and without diabetes: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (1988-2011). Diabetes Care 2017;40:453-60. 10.2337/dci16-0042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liu L, Chen X, Liu Y, et al. The association between fasting plasma glucose and all-cause and cause-specific mortality by gender: The rural Chinese cohort study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2019;35:e3129. 10.1002/dmrr.3129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhou L, Mai JZ, Li Y, et al. Fasting glucose and its association with 20-year all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Chinese general population. Chronic Dis Transl Med 2018;5:89-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplementary material