Abstract

Background

Extant literature warns of elevated suicide risks in adults post-bariatric surgery, making understanding risks for adolescent patients imperative.

Objectives

To examine prevalence and predictors/correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) in adolescents with severe obesity who did/did not undergo bariatric surgery from presurgery/baseline to 4 years postsurgery.

Setting

Five academic medical centers

Method

Utilizing a prospective observational design, surgical adolescents (n=153; 79% female, 65% White, Mage=17, MBMI=52) and nonsurgical comparators (n=70; 80% female, 54% White, Mage=16, MBMI=47) completed psychometrically sound assessments at presurgery/baseline and postsurgery Years 2 and 4 (Year 4: n=117 surgical [MBMI=38], n=56 nonsurgical [MBMI=48]).

Results

For the surgical group, rates of STBs were low (Year 2 [1.3–4.6%]; Year 4 [2.6–7.9%], similar to national base rates. Groups did not differ on a Year 4 postsurgical STBs composite (PostSTBs: ideation/plan/attempt; n=18 surgical [16%], n=10 nonsurgical [18%]; OR=0.95,p=0.90). For the surgical group, predictors/correlates identified within the broader suicide literature (e.g., psychopathology [ps<.01], victimization [ps<.05], dysregulation [p<.001, drug use [p<.05], knowing an attemptor/completer [p<.001]) were significantly associated with PostSTBs. Surgery-specific factors (e.g., % weight loss, weight satisfaction) were nonsignificant. Of those reporting a lifetime attempt history at Year 4, only a minority (4/13 surgical, 3/9 nonsurgical) reported a first attempt during the study period. Of 3 decedents (2 surgical, 1 nonsurgical), none were confirmed suicides.

Conclusions

The current study indicates that undergoing bariatric surgery in adolescence does not heighten (or lower) risk of STB engagement across the initial 4 years postsurgery. Suicide risks present prior to surgery persisted, and also newly emerged in a subgroup with poorer psychosocial health.

Keywords: adolescent, young adult, suicidal behavior, suicide, bariatric surgery

Suicide prevention is a public health priority. Extant literature warns of elevated suicide behavior risks in adults pre and/or post bariatric surgery. These risks include higher rates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) and/or history of self-harm in pre- and postsurgical patients and higher postsurgery suicide deaths relative to nonsurgical controls or population base rates.1–4 While suicide deaths are small in number, estimated at about 1% over a 12 year period in a large comprehensive study,5 they bear devastating consequences. Across this literature, there is a call for assessment and close monitoring of suicidal behaviors in patients postsurgery, and for comprehensive studies aimed at understanding why, when, how, and in whom suicide risks unfold.6

As the empirical base establishing the safety and efficacy for bariatric surgical procedures in adolescent patients matures, understanding suicide risks is imperative when placed in the broader context of national epidemiological data. STBs typically begin and then increase across the adolescent and young adult (AYA) years.7–9 Moreover, the suicide rate for AYAs reached their highest point this century in 2017,8 with suicide as the second leading cause of death among 10–25 year olds.10 Further, a series of reports accessing the biennial Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (YRBSS) demonstrated that having obesity conferred significantly greater risks of engaging in STBs during adolescence relative to being of healthy weight.11–14 In fact, those of severe obesity status were nearly 2 times more likely to have reported suicidal ideation in the past year.13

The most comprehensive examinations of STBs and associated risk factors were recently published by the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium and focus on adults postsurgery. In an initial report,15 approximately 1 in 4 (25.7%) reported a presurgery history of STBs, of whom nearly half (46.3%) also reported STBs during the initial 5 years postsurgery, including 13 nonfatal suicide attempts (0.8%). While several presurgical predictors and postsurgical correlates were identified (e.g., mental health status and related care utilization), STBs were unrelated to % excess weight loss. Seven (17.5%) of the 40 postsurgery deaths observed over the 5-year study period in the original sample (n=2,458) were categorized as suicides (n=3) or “potential” suicides (n=4; “drug poisoning”). A subsequent analysis at 7 years16 further warned of higher than expected drug- and alcohol-related overdose deaths following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), specifically.

Our initial understanding of suicide risks in the adolescent bariatric patient is limited to 3 studies, representing three surgical procedures (RYGB, sleeve gastrectomy [SG], and adjustable gastric banding [AGB]). Together, these initial studies document a varied history of STBs, and in a minority of patients ranging from 13–40%, pre- and/or post-surgically.17–19 Adolescents who had poor mental health and/or lower quality of life, pre- and/or postsurgery were at increased risk of STBs.18,19 Importantly, each study has notable weaknesses (i.e., retrospective chart reviews, cross-sectional, single-item metrics) and were limited to postsurgery follow-up ≤ 2 years. Two suicide deaths were reported from one of these study groups, yet timing of death (i.e., pre- versus post AGB) was not stated.18 However, a related prospective study from the same group reported only one known suicide death which occurred between postsurgery years 3 and 5.20 To our knowledge, this is the only reported suicide death in the broader adolescent bariatric outcome literature to date.21–24

The present study tracked adolescents who underwent bariatric surgery across the first 4 postsurgical years and prospectively characterized STBs (ideation, plans, attempts). Lifetime history of attempts were also documented. A contemporaneous nonsurgical group with severe obesity was tracked in parallel. Based on the aforementioned literatures (adolescent bariatric surgery, national surveillance), we hypothesized there would be a subgroup of adolescents who underwent bariatric surgery who experienced STBs, pre- and/or postsurgery. To begin to understand whether undergoing bariatric surgery is associated with heightened suicide risks in this age group, we explored whether presence of postsurgery STBs differed between surgical and nonsurgical groups. In addition, and to inform clinical monitoring targets, we explored what factors may increase the likelihood of a patient engaging in STBs postsurgery. These factors included surgery-related factors (i.e., BMI, percent weight loss, procedure type) as well as patient-reported outcomes related to weight and health (weight satisfaction, physical health and weight-related quality of life [WRQOL]). Additional explanatory factors included were based on the broader adolescent suicide literature, many of which are known correlates of severe obesity in adolescence, including adolescents who undergo bariatric surgery. These included: psychopathology (i.e., depressive symptoms, externalizing symptoms)7,25–28 and disordered eating,29–32 as well as high risk contexts of a history of child maltreatment,33,34 peer victimization and weight-specific peer group experiences,35–37 and exposure to nonfatal attempts or suicide deaths in family or friends.38 The co-occurrence of high risk behaviors and contexts including hazardous alcohol use,39,40 illicit drug use,38,41 and impulsivity/dysregulation38,42 were also explored.

METHODS

Overview of Study Design

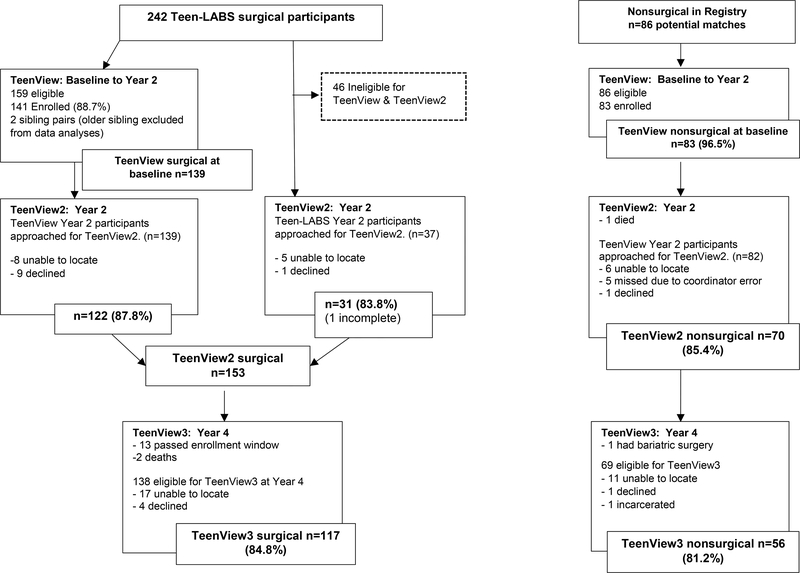

Participants in the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases’ Teen Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery consortium (NIDDK Teen-LABS NCT00474318; n=242, ages 13–19), a multi-site prospective observational safety and efficacy study,21 were invited if eligible (i.e., age ≤ 18 years) to participate in a parallel series of independently funded studies (TeenView series) tracking psychosocial health outcomes from presurgery and across the first four postsurgery years. The TeenView series recruited a comparator group (“nonsurgical”) of demographically similar adolescents with severe obesity from the 5 Teen-LABS sites. Eligibility criteria and presurgery enrollment for the parent and initial TeenView study were previously described.21,34 With additional funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, TeenView participants retained at Year 2, as well Teen-LABS participants initially ineligible for TeenView due to age (i.e., > 18 years old at baseline), were approached for TeenView2. Further, participation in TeenView2 was an eligibility criterion for TeenView3 at Year 4. Study aims were focused on high-risk behaviors, including suicidal behaviors. Respective study protocols were approved by site Institutional Review Boards. Recruitment/participation information are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment and retention.

Study Procedures

Data from presurgery/baseline, Year 2, and Year 4 were utilized. Participants provided written assent/consent at each study phase and were told their responses would remain confidential except in cases of past or current potential for serious harm to self, as detailed below. A comprehensive battery of assessments and validated self-report measures were administered and are summarized in Table 1. Baseline assessments were completed at in-person research visits at a Teen-LABS site with trained personnel administering paper/pencil forms. Visits at Years 2 and 4 occurred onsite or at home via a secure web-based portal or paper/pencil. When home-based, height and weight measurements were obtained via field visits by study affiliates21 (Year 2 n=20 surgical; Year 4 n=21 surgical) or self-reported (Year 2, n=5 nonsurgical; Year 4, n=6 surgical; n=56 nonsurgical).

Table 1.

Assessments at Baseline (B), Year 2 (Y2) and Year 4 (Y4).

| Suicidal Tdoughts and Behaviors (STBs) | Measure | Timepoint | ||

| B | Y2 | Y4 | ||

| Ideation (past 2 weeks) | Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) | x | x | x |

| Ideation (past month) | Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ) or Adult SIQ (ASIQ)a,b | x | ||

| Ideation, Plan, Attempt (past year) | Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS)b | x | x | |

| Attempts in Lifetime | Suicide History Form (SHF)b | x | ||

| Predictors and Correlates of STBs | Measure | Timepoint | ||

| B | Y4 | |||

| Surgical Factors | ||||

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Measured height/weight ratio (kg/m2) | x | x | |

| Procedure | RYGB vs SG | x | ||

| % weight change | ((weightpresurgery-weightYear4)/weightpresurgery)*10 | x | ||

| Weight Satisfaction and Quality of Life | ||||

| Weight Satisfaction | “How satisfied are you with your current weight?” (1=extremely dissatisfied to 5=extremely satisfied) | x | ||

| Physical Health Related Quality of Life | Short Form-36 (SF-36): Physical Health Composite Score | x | x | |

| Weight-Related Quality of Life | Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Kids (IWQOL-Kids) or IWQOL-Lite: Total a | x | x | |

| Psychopathology and Loss of Control Eating | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms | BDI-II: Total Score | x | x | |

| Externalizing Symptoms | Youth Self Report (YSR) or Adult Self Report (ASR): Externalizing Score a | x | x | |

| Loss of Control Eating (LOC) | Questionnaire of Eating Weight Patterns-Revised (QEWP-R): 2 itemsc | x | x | |

| High Risk Contexts | ||||

| Negative Peer Experiences | Revised Peer Experience Questionnaire (RPEQ): Total Relational & Reputational victimization IWQOL-Kids: Social Life Score | x | ||

| Child Maltreatment | Child Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ): >Moderate severity classification | x | ||

| Exposure to Suicide | Know any family, friends, classmates, or coworkers made nonfatal or fatal attempts | x | ||

| High Risk Behaviors | ||||

| Dysregulation | Dysregulation Inventory (DI): Total Score | x | ||

| Hazardous Alcohol Consumption | Alcohol Use Disorders Test (AUDIT)d | x | ||

| Illicit Drug Use | Monitoring the Future (MTF)e | x | ||

Measure given based on age (<19 years old versus ≥19 years old).

These measures at Year 4 were included as part of the composite postSTB score.

Endorsed yes to: “During the past 6 months, have you had times when you eat continuously during the day or parts of the day without planning what and how much you would eat?”; and “Did you experience a loss of control, that is, you felt like you could not control your eating?”.

Endorsed “≥3 drinks per occasion on a typical drinking day” or “≥6 drinks on >1 occasion” in past year.

Any past year use not prescribed by a doctor of Marijuana, LSD, Hallucinogens other than LSD, Cocaine, Amphetamines, Barbiturates, Tranquilizers, Heroin, Narcotics other than heroin, or Inhalants

STB assessment increased in depth over time and included both current and past thoughts/feelings/events. Methods of administration varied and subsequent risk assessments were deliberately thorough given potential for safety concerns. Studies’ Data Safety Monitoring Plans identified specific items from measures of STBs that were deemed “safety action items” (i.e., current ideation, future intent, or any history of previous suicide attempt) which would prompt a protocolized risk assessment by a licensed Study Psychologist. Specifically, for measures assessing “current” STBs (i.e., within past 2 weeks, month), administration occurred in person or via phone by trained staff to allow for risk identification in “real-time” and to facilitate an immediate response by the Study Psychologist if needed. For measures assessing past STBs (i.e., past year, lifetime), administration occurred via web with an automated alert sent to research staff by email if safety action items were endorsed by the participant. Then, for those participants and within 7 days, the Study Psychologist completed risk assessments in person or by phone, and per protocol, assessed for current risk and lethality, facilitated emergency services as needed, and identified appropriate care referrals in the participant’s local area. At Year 4, participants who endorsed any safety action items were additionally provided with the toll-free National Suicide Prevention Lifeline phone number and sent a secured email summarizing all potential resources discussed.

Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors (STBs) Assessments

Current Suicidal Ideation (“past 2 weeks”)

Participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II43) at presurgery/baseline, Year 2 and Year 4, as a measure of depressive symptoms (see below). There is a single-item on the BDI-II that asks about current suicidal ideation in the “past 2 weeks”. We included this suicidal ideation item in descriptive analyses only, as it has been reported in aforementioned adolescent (i.e., AMOS19) and adult (i.e., LABS15) bariatric surgery outcome studies as an indicator of suicidality. For these descriptive analyses, an endorsement of one of three response options, “I would like to kill myself” and “I would kill myself if I had the chance” (both safety action items), as well as third response option, “I have thoughts of killing myself, but I would not carry them out” were coded as “current ideation,” with the fourth response of “I don’t have any thoughts of killing myself” coded as “no current ideation.”

Recent Suicidal Ideation (“past month”)

At Year 4, participants completed the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ44) or if >19 years of age, the Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (ASIQ45,46). The SIQ/ASIQ assessed the frequency of ideation in the past month from 0 “I never had this thought” to 6 “... almost every day.” While the majority of items are identical across measures, the SIQ contains 5 additional items found to be developmentally appropriate only for adolescents. A total score is summed with recommended clinical cut-points (SIQ ≥ 41, ASIQ ≥ 31) and manual-identified safety action items.

Past year STBs

At Years 2 and 4, participants completed questions from the YRBSS regarding suicidal behaviors “during the past 12 months”47 including any suicidal ideation (“… did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?”), suicidal plan (“… did you make a plan about how you would attempt suicide?”), or suicide attempt (“… how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” [dichotomized as none=0, any=1]). All were considered safety action items.

Lifetime Suicide Attempt History

At Year 4, participants completed a lifetime Suicide History Form (SHF) designed for the current study. Participants answered yes or no to: “Has there been a time in the past when you ever tried to kill yourself? Include any attempt in which there was an intent to die, including attempts that were interrupted or aborted.” A positive endorsement prompted responses to the “total number of attempts,” “age at first attempt,” “age at most recent attempt,” and methods (i.e., “poisoning, drugs,” “knife or sharp object”). All were considered safety action items.

PostSTB Composite

A composite of postsurgery suicidal thoughts and behaviors score (PostSTBs: 0=none, 1=any) was computed and defined as any endorsement at Year 4 of past-year ideation/plan/attempt (YRBSS), past-month clinical range suicidal ideation (ASIQ/SIQ) or any postsurgery attempt from baseline to Year 4 (SHF).

Potential Predictors and Correlates of PostSTBs

Potential predictors and correlates of the PostSTB composite focused on 5 domains. Surgical factors, were defined as surgery type (RYGB versus sleeve gastrectomy [SG] only), BMI (kg/m2), and percent weight change from pre-surgery/baseline to Year 4. The additional four domains (detailed in Table 1) included: patient-reported outcomes related to weight and health (i.e., weight satisfaction, weight-related48,49 and health-related quality of life50), psychopathology/disordered eating (i.e., depressive symptoms,43 externalizing symptoms,51,52 loss of control eating [LOC]53), high risk contexts for suicide (i.e., negative peer experiences,48,54 history of child maltreatment,55 social exposure to suicide38), and high risk behaviors (i.e., dysregulation,56 hazardous alcohol consumption,57,58 illicit drug use59).

Other Measures

Participants completed a demographics form. At each timepoint, participants self-reported current use of medication for psychiatric or emotional problems (i.e., antidepressants, major or minor tranquilizers, mood stabilizers, stimulants) which were combined and dichotomized (0=none; 1=any use). Participants also reported past 12-month engagement in outpatient mental treatment (0=none; 1=any) as well as inpatient psychiatric hospitalization(s) (0=none; 1=any).

Data Analyses

Missing data ranged from 0.01–7.1% for all variables of interest and were handled via maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus (Version 7.11). The nesting of participants within the five sites was controlled in hypothesized analyses via specialized variable and analysis commands to avoid Type-1 errors. T-tests and chi-square tests were used to examine demographics and BMI for surgical/nonsurgical groups and completers/noncompleters of Year 4 assessments.

Prevalence or means/standard deviations were calculated for all variables of interest. For the surgical group, a series of separate logistic regressions examined each potential predictor/correlate of PostSTBs, with sex, age, race, and baseline caregiver education controlled. Individual predictor/correlates fell into 5 domains, including surgical factors, patient-reported outcomes related to weight and health, psychopathology/disordered eating, high risk contexts for suicide, and high risk behaviors. Separate models were utilized due to sample size and the low prevalence of suicidal behaviors. Confidence intervals (CI) were generated with a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 re-samples.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

As detailed in Table 2, the majority of adolescents self-identified as White and of female sex, with the surgical group older (p <.001) relative to nonsurgical. At Year 4, 5 were currently completing high school, with the majority high school graduates and either engaged in post-secondary education and/or working full- or part-time. Most continued to live with parents or other relatives and were not married/engaged. Relative to nonsurgical, surgical participants presented with a higher baseline BMI (p<.001), but by Year 4, had lower BMI (p<.001) and a greater percent change in weight (surgical: −24.5%; nonsurgical: +6.1%; p<.001).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of adolescents in the surgical and nonsurgical groups.

| Surgical | Nonsurgical | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | Mean ± SD n (%) | Mean ± SD n (%) | pa |

| Baseline | n=153 | n=70 | |

| Age | 17.04 ± 1.44 | 16.10 ± 1.38 | <0.001 |

| Gender (% Female) | 121 (79.1%) | 56 (80.0%) | 0.88 |

| Race (% White) | 99 (64.7%) | 38 (54.3%) | 0.14 |

| Caregiver Education (% ≤ High School Graduation) b | 61 (41.5%) | 33 (47.1%) | 0.43 |

| BMI (pre-surgery/baseline) | 52.21 ± 8.49 | 46.53 ± 5.83 | <0.001 |

| Surgical Procedure | |||

| Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass | 98 (64.1%) | ||

| Sleeve Gastrectomy | 47 (30.7%) | ||

| Adjustable Gastric Band | 8 (5.2%) | ||

| Year 2 | n=153 | n=70 | |

| BMI c | 36.48 ± 8.81 | 48.84 ± 8.53 | <0.001 |

| % Change in Weightd | −29.79 ± 11.67 | 7.35 ± 10.70 | <0.001 |

| Year 4 | n=117 | n=56 | |

| Age | 21.28 ± 1.50 | 20.52 ± 1.40 | <0.001 |

| BMIe | 38.33 ± 9.80 | 48.05 ± 10.83 | <0.001 |

| % Change in Weightf | −24.49 ± 15.45 | 6.08 ± 17.40 | <0.001 |

| High School Graduate/GEDg | 103 (93.6%) | 47 (87.0%) | 0.16 |

| In school or workingh | 89 (80.9%) | 40 (72.7%) | 0.23 |

| Living with Parent(s) or other relativesh | 75 (68.2%) | 41 (74.5%) | 0.40 |

| Not Married or Engagedh | 94 (85.5%) | 50 (90.9%) | 0.32 |

Abbreviations: BMI= Body Mass Index

p-values are based on two-tailed independent t-tests when examining mean values and on Chi-Square tests when examining percentages.

Missing for n=6 surgical.

Missing for n=7 surgical and n=8 nonsurgical

((weight24-months -weightpre-surgery/baseline) /weightpre-surgery/baseline)*100; Missing for n=5 surgical and n=8 nonsurgical

Missing for n=2 surgical and n=5 nonsurgical.

((weight48-months -weightpre-surgery/baseline) /weightpre-surgery/baseline)*100; Missing for n=4 nonsurgical

Missing for n= 7 surgical and n=2 nonsurgical

Missing for n= 7 surgical and n=1 nonsurgical

No significant differences were identified between participants who completed Year 4 assessments (n=173) and those who did not (n=50) for group status (surgical versus nonsurgical), race, age or baseline BMI. However, a significantly greater percentage of males did not complete Year 4 assessments (16 of 46, 34.8%) than females (34 of 177, 19.2%; X2=5.09, p=0.02).

PostSTBs

Rates of suicidal ideation (within past 2 weeks, month, and year) and making a suicidal plan and/or attempt (within past year) at presurgery/baseline, Year 2 and Year 4 are reported in Table 3. Ideation, plan, and attempt prevalence were low for both groups, with the majority of participants reporting no STBs.

Table 3.

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors at Baseline, Year 2 and Year 4 for adolescents in the surgical group and nonsurgical group.

| Baseline | Year 2 | Year 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical (n=153) | Nonsurgical (n=70) | Surgical (n=153) | Nonsurgical (n=70) | Surgical (n=117) | Nonsurgical (n=56) | |

| Ideation | ||||||

| Past 2 weeks (BDI-II)a | 17 (11.2%) | 13 (18.6%) | 6 (4.1%) | 12 (17.9%) | 4 (3.7%) | 6 (11.5%) |

| Past month (SIQ/ASIQ)b | 5 (4.4%) | 4 (7.4%) | ||||

| Past year (YRBSS)c,d | 6 (4.0%) | 8 (12.1%) | 9 (7.9%) | 5 (8.9%) | ||

| Plan | ||||||

| Past Year (YRBSS)c,d | 7 (4.6%) | 3 (4.5%) | 8 (7.0%) | 1 (1.8%) | ||

| Attempt History | ||||||

| Past year (YRBSS)c,d | 2 (1.3%) | 2 (3.0%) | 3 (2.6%) | 3 (5.4%) | ||

| Lifetime (SHF)d | 14 (12.3%) | 10 (17.9%) | ||||

| Median number of lifetime attempts (SHF)e | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Mean age 1st attempt (SHF)d | 15.31 ± 2.78 | 14.70 ± 2.41 | ||||

Abbreviations: BDI-II=Beck Depression Inventory-II; SIQ=Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire; ASIQ=Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire; SHF=Suicide History Form; YRBSS=Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System

Any endorsement of suicidal thoughts on item 9 of the BDI-II. Missing for n=1 surgical at baseline; Missing for n=5 surgical and n=3 nonsurgical at Year 2; missing for n=8 surgical at Year 4 and n=4 nonsurgical at Year 4.

Missing for n=3 surgical and n=2 nonsurgical at Year 4. For the combined sample (surgical and nonsurgical), mean raw scores for the SIQ/ASIQ were: SIQ: M=11.00±18.38 (n=13) and ASIQ: M=5.38±12.01 (n=154). Mean percentile scores were: SIQ: M=35.85±33.56 (n=13) and ASIQ: M=33.32±26.58 (n=153).

Missing for n=2 surgical and n=4 nonsurgical at Year 2.

Missing for n=3 surgical and n=0 nonsurgical at Year 4.

Missing for n=1 of 14 surgical who endorse a lifetime history of attempt.

At Year 4, 14 of 114 (12.3%, n=13 females, n=1 male) in the surgical group reported a history of one or more suicide attempts in their lifetime. Of those, 13 surgical participants provided age of first attempt, with 9 first attempting suicide prior to surgery/study enrollment. Eight of those 9 also provided age at most recent attempt, with 5 attempting again during the 4-year study period. In addition, 4 reported a first attempt postsurgery. Thus, a total of 9 of 114 adolescents reported at least one attempt postsurgery (7.9%). When asked to endorse a method(s) used in an attempt(s) over their lifetime, the most common method among surgical participants was intentional poisoning by drug ingestion (n=12), followed by use of a knife/sharp object (n=9), suffocation/hanging (n=5), poisoning solids/liquids (n=1), and drowning (n=1).

For nonsurgical, 10 of 56 (17.9%, n=9 females, n=1 male) reported one or more suicide attempts in their lifetime. Of those, 9 nonsurgical provided age of first attempt, with 6 first attempting suicide prior to study enrollment. Five of those 6 provided age at most recent attempt, with 2 attempting again during the 4-year study period. Three reported their first suicide attempt was post-enrollment. Most frequent methods of attempt included use of a knife/sharp object (n=6); followed by intentional poisoning by drug ingestions (n=3), drowning (n=1), and stepping in front of car (n=1).

Predictors and Correlates of the PostSTB Composite

Eighteen (16.4%) surgical participants and 10 (18.2%) nonsurgical met criteria for the PostSTB composite. Logistic regression controlling for demographic variables indicated engagement in PostSTBs was unrelated to group status (surgical vs. nonsurgical: Odds Ratio [OR]=0.95; 95%CI:0.42–2.14; p=0.90). Given this nonsignificant finding and our specific research interests, predictors and correlates of the PostSTB composite were examined for the surgical group only (Table 4). The initial regression model examined demographic variables, with participants self-identifying as female (OR=4.56, p<0.001) having higher odds of engaging in PostSTBs (female: 17 of 90 [19%]; male: 1 of 20 [5%]), with other demographic variables nonsignificant (non-White race [OR=1.88, p=0.08], age [OR=0.93, p=0.73], caregiver education [OR=0.51, p=0.16]). These variables were included as control variables in each subsequent regression model. Significant presurgical/baseline predictors of engaging in postsurgery PostSTBs included lower WRQOL, greater depressive symptomatology, greater externalizing symptomatology, screening positive for LOC eating, greater peer victimization, and greater impact of weight on peer experiences. Significant postsurgery (Year 4) correlates included lower WRQOL and physical QOL, greater depressive symptomatology, greater externalizing symptomatology, greater dysrégulation, illicit drug use in the past year, and exposure to someone who attempted or completed suicide, with hazardous alcohol consumption marginally significant.

Table 4.

Baseline predictors and Year 4 correlates of postsurgery suicidal thoughts and behaviors (PostSTBs)a for surgical participants (N=153).

| OR | 95% CI OR | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Predictor Models b | ||||

| Model | ||||

| 1 | BMI | 0.97 | 0.92 – 1.03 | 0.32 |

| 2 | Surgical Procedurec | 1.67 | 0.65 – 4.31 | 0.29 |

| 3 | Physical Health-Related Quality of Life (SF-36) | 0.95 | 0.88 – 1.02 | 0.16 |

| 4 | Total Weight-Related Quality of Life (IWQOL-Kids) | 0.96 | 0.94 – 0.98 | <0.001 |

| 5 | Peer Victimization (RPEQ)d | 1.52 | 1.01 – 2.28 | 0.04 |

| 6 | Weight-Related Peer Experiences (IWQOL-Kids) | 0.98 | 0.96 – 1.00 | 0.02 |

| 7 | Child Maltreatment (CTQ)d | 3.57 | 0.55 – 23.06 | 0.18 |

| 8 | Depressive symptoms (BDI-II) | 1.09 | 1.04 – 1.14 | <0.001 |

| 9 | Externalizing Symptoms (YSR)d | 1.07 | 1.02 – 1.13 | 0.007 |

| 10 | Loss of Control Eating | 4.90 | 1.94 – 12.39 | 0.001 |

| Year 4 Concurrent Models b | ||||

| 11 | BMI | 0.99 | 0.94 – 1.03 | 0.53 |

| 12 | % Weight Loss | 1.00 | 0.99 – 1.02 | 0.84 |

| 13 | Weight Satisfaction | 0.93 | 0.69 – 1.25 | 0.63 |

| 14 | Physical Health-Related Quality of Life (SF-36) | 0.96 | 0.95 – 0.97 | <0.001 |

| 15 | Total Weight-Related Quality of Life (IWQOL-Kids/IWQOL-Lite) | 0.97 | 0.95 – 0.99 | 0.007 |

| 16 | Depressive Symptoms (BDI-II) | 1.17 | 1.11 – 1.22 | <0.001 |

| 17 | Externalizing Symptoms (ASR) | 1.09 | 1.04 −1.15 | <0.001 |

| 18 | Loss of Control Eating | 1.50 | 0.27 – 8.37 | 0.65 |

| 19 | Know Attemptor (SHF) | 1.91 | 1.49 – 2.44 | <0.001 |

| 20 | Know Completor (SHF) | 4.86 | 2.19 – 10.80 | <0.001 |

| 21 | Dysregulation (DI) | 1.02 | 1.02 – 1.03 | <0.001 |

| 22 | Hazardous Drinking (AUDIT) | 2.19 | 0.97 – 4.93 | 0.06 |

| 23 | Illicit Drug Use | 2.59 | 1.19 – 5.64 | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: AUDIT: Alcohol Use Disorders Test; ASR: Adult Self-report; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; BMI: Body Mass Index; CI: Confidence Interval; CTQ: Child Trauma Questionnaire; DI: Dysregulation Inventory; IWQOL: Impact of Weight on Quality of Life; OR: Odds Ratio; RPEQ: Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire; SF-36: Short Form 36; SHF: Suicide History Form; YSR: Youth Self-Report

For each model, the dependent variable was PostSTBs (0=none, 1=any), measured at Year 4.

In a separate logistic regression, the effects of demographic variables on PostSTBs were examined. Findings: female gender (OR=4.56, p<0.001), non-White race (OR=1.88, p=0.08), age (OR=0.93, p=0.73), and caregiver education (OR=0.51, p=0.16). These variables were included as control variables for each of the predictor and concurrent models above.

For this model, participants receiving the adjustable gastric band were excluded, and comparisons were made between the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (0) versus sleeve gastrectomy (1).

These measures were available for a subsample of Surgical participants (n=122) who also participated in the TeenView study.

Mental Health Care

Mental health care, including current medication use, and outpatient or inpatient psychiatric treatment or counseling in the past year at each timepoint are provided in Table 5 for the surgical participants who did/did not meet criteria for the PostSTB composite. While inpatient hospitalizations were infrequent (i.e., 7 inpatient admissions over time across 4 participants), approximately half of those who engaged in PostSTBs reported outpatient care and/or current medication use prior to/at time of surgery and at Year 4. At all timepoints, participants who engaged in PostSTBs reported higher engagement in mental health care.

Table 5.

Psychiatric treatment history of surgical participants who did/did not endorse postsurgery suicidal thoughts and behaviors (PostSTBs) at Year 4.

| Surgical | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Year 2 | Year 4 | ||||

| PostSTBs n=18 |

No PostSTBs n=92 |

PostSTBs n=18 |

No PostSTBs n=92 |

PostSTBs n=18 |

No PostSTBs n=92 |

|

| Current psychiatric medication | 9 (52.9%)a | 12 (13.5%)b | 7 (38.9%) | 15 (17.0%) c | 8 (53.3%)b | 13 (14.8%) c |

| Psychiatric hospital admission in past 12 months | 3 (16.7%) | 8 (8.8%) a | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (1.1%) c | 2 (13.3%)b | 1 (1.1%) c |

| Psychiatric outpatient treatment in past 12 months | 10 (55.6%) | 22 (24.2%) a | 7 (38.9%) | 11 (12.5%) c | 10 (66.7%)b | 8 (9.1%) c |

Missing for n=1

Missing for n=3

Missing for n=4

Deaths

Of the 3 deaths previously reported by the parent Teen-LABS study,23 2 of the decedents were participants in the TeenView series (2 of 169 surgical, or 1.2%), whose deaths occurred between Year 2 and Year 4 assessments. Both were females who underwent RYGB, with coroner-based cause of death documented as “acute combined drug toxicity”, with no determination whether intentional (i.e., self-harm/suicide) or accidental. One of these surgical decedents had a notable history of treatment for mental health concerns. In the nonsurgical group, there was one known death (1 of 83 or 1.2%), discovered during unsuccessful attempts to contact/schedule for the Year 2 assessment, and confirmed via an online obituary search. Cause of death was unknown, with no further details available. None of the TeenView decedents endorsed STBs (within past 2 weeks, month and year) when last assessed, with all 3 having died prior to the comprehensive Year 4 assessments which included a full lifetime history of prior attempts.

DISCUSSION

Utilizing a controlled design, the present study suggests suicide risks were not heightened (nor lowered) in adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery across the initial 4 years postsurgery, even in differing contexts of clinically significant weight loss (surgical) versus progressive weight gain (nonsurgical). Findings should be considered preliminary given the small sample size to detect what are low prevalence behaviors, even in the general population. However, rates of ideation, plans, and attempts at Year 4 were consistent with national base rates during a similar study window (e.g., during 2015 for 18–25 year olds: ideation≈8.3%, plan≈2.7%, attempts≈1.6%).60 While these outcomes reported herein fell within “age-normative” ranges, their impact should not be interpreted as benign. In the present sample, suicide risks that were present prior to surgery persisted, and also newly emerged in a subgroup with poorer psychosocial health. Two thirds of AYA with a postsurgery nonfatal attempt also reported a previous attempt before surgery.

The potency of a presurgical attempt history signaling later suicidal risks has been reported in adult patients.15,61 However, rates of attempts postsurgery were notably higher in our younger age group relative to LABS adults (Teen-LABS surgical: 9/114 [7.9%] vs LABS surgical: 13/1534 [0.8%]).15 The number of attempts in this AYA subgroup was also notable, with 1 in 3 surgical group attempters (38.5%) reporting a history of 3 or more attempts in their lifetime as compared to 1 in 5 nonsurgical attempters. The broader AYA literature indicates a previous nonfatal attempt as the prominent risk factor for a future attempt or suicide death.62,63 Therefore, while not an absolute contraindication for surgery, understanding nonfatal attempt history appears to be highly relevant. Similar to adults in LABS,15 STBs were not related to objective surgical metrics (e.g., baseline BMI, percent weight lost, Year 4 BMI outcome). While Teen-LABS was not designed as a procedural comparative trial, STB rates postsurgery were similar between those who underwent RYGB and SG (i.e., attempts in 5 RYGB vs. 4 SG). In contrast, patient-reported outcomes regarding weight and health provided unique insights. While unrelated to current weight satisfaction at Year 4, those who perceived a greater negative impact of weight and physical health on their day-to-day life (i.e., lower QOL) were more likely to report STBs postsurgery, similar to findings from LABS linking perceptions of a postsurgery decline in general health with suicidality.15

The remaining predictors and correlates of STBs were known risk factors for suicidality in the general AYA literature, yet are documented in this unique clinical population for the first time. AYAs who reported greater depressive or externalizing symptomatology, whether pre- or postsurgery, were at higher risk for postsurgical STBs, confirming initial reports by other investigators,18,19 yet extending postsurgery follow-up to Year 4. LOC eating is the most common form of presurgery disordered eating in this clinical group.31 While often remitting postsurgery,32 LOC presence presurgery is a known indicator of poor mental health28 and now, increased STB risks. Many adolescents who undergo bariatric surgery experience peer victimization and weight-related negative peer experiences (i.e., lower social WRQOL),36,37 risk factors for suicidal behaviors in the broader literature35 and supported herein. Moreover, the social context of suicide exposure was common in the PostSTB group. Post hoc, nearly half (44%) were exposed to a friend or family member who had made a nonfatal suicide attempt, and 1 in 3 a suicide death. In the general population, including adolescents, recent estimates indicate that 1 in 5 know someone in their social network who died by suicide.64

Finally, STBs and other risky behaviors (i.e., illicit drug use, hazardous alcohol use, or psychological dysregulation) co-occurred in our sample, consistent with the general AYA population.38,39,41 Post hoc review indicated approximately half of those who engaged in STBs postsurgery also reported illicit drug use (10 of 18 [55.6%]) and/or hazardous alcohol use (7 of 18 [46.7%]). While the most common substance used in the surgical PostSTB group was marijuana (9 of 10), use of barbiturates, tranquilizers, and/or narcotics was also reported. In a previous report at Year 2 with these participants,40 warnings of safety concerns regarding adolescents’ postsurgical hazardous alcohol were relayed particularly given pharmacokinetic evidence of elevated risk of intoxication and impairment postsurgery.65 Moreover, when these Year 4 data are considered against adult evidence indicating elevated risks postsurgery for drug- and alcohol-related deaths and self-harm via drug poisoning,15,16,61,66concern is warranted. To date there have been no confirmed suicide deaths in the present subsample, nor the larger parent Teen-LABS consortium to Year 5.23 However, the documented cause of death for 2 surgical group decedents (i.e., “acute combined drug toxicity”), even in the absence of understanding intent (i.e., accidental vs. intent of self-harm vs. intent of suicide), is troubling. In addition to these decedents, the most common nonfatal attempt method was “intentional poisoning by drug”, a method on the rise in the general population, and for females in particular.67,68

Suicide risk reduction is a public health priority for all AYAs, including adolescents with severe obesity who undergo bariatric surgery. The present data provide guidance on clinical assessment and monitoring targets, many of which are already AYA public health targets for risk reduction in their own right (i.e., alcohol use, illicit drug use, psychopathology) or for adolescents after bariatric surgery specifically (i.e., alcohol40,69). To date, adolescent bariatric guidelines only address suicide by the inclusion of “current suicidality” as a contraindication for surgical candidacy.69–71 Any attempt history, whether presurgical or postsurgical, should be a strong indication for close monitoring as well as a comprehensive treatment plan supporting mental health. A history of suicide in the patient’s social network should be routinely assessed. Irrespective of weight status/weight loss outcomes, discussions regarding patient experiences of weight and health burden on their daily life (i.e., QOL) are clinically indicated. Encouragingly, approximately half of those with STBs postsurgery reported engagement in outpatient mental health treatment or psychiatric medication use, at rates higher than those who did not report STBs. Nonetheless, and as seen in the broader AYA suicide literature,7,72 a notable percentage of AYA who experience postsurgical STBs did not receive any mental health care.

The Joint Commission recently updated recommendations for suicide risk screening to occur across all medical settings via validated measures (www.jointcommission.org/topics/suicide_prevention_portal.aspx). One example, the NIMH Ask Suicide-Screening Questions Toolkit (www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-conducted-at-nimh/asq-toolkit-materials/index.shtml), contains a validated, freely available suicide risk screening tool in multiple languages for youth (ages 10–21)73 and related tools for patient safety management.74 Bariatric programs are encouraged to designate clinical team members (e.g., nurse practitioner, social worker, psychologist) for AYA suicide risk assessment training and to develop clinical pathways with appropriate community resources. Ongoing monitoring should extend beyond the surgical program to all pediatric healthcare settings as these patients transition to adult care.

Teen-LABS and associated TeenView series provide the most comprehensive prospectively collected data characterizing adolescent RYGB and SG outcomes, enhanced by ancillary inclusion of nonsurgical comparators. Participants were predominantly White, female, and between the ages of 13 and 19 at time of surgery, limiting generalizability, yet consistent with national adolescent bariatric surgery trends.75 Moreover, although AYA males remain at higher risk for suicide deaths in general,8 recent work has revealed greater rates of increase in AYA female emergency and inpatient hospital encounters for STBs, and a narrowing of the gender gap in suicide deaths.9,76,77 While our STB assessments were comprehensive, particularly at Year 4, gaps were still present. For instance, the pre-surgery/baseline assessment was limited to “current” suicidality on one BDI-II item. Indeed, only a small percentage of the surgical group reporting PostSTBs also endorsed current suicidality on this item, whether at pre-surgery/baseline (n=4, 22.2%), Year 2 (n=3, 16.7%), or Year 4 (n=4, 26.7%). This demonstrates that assessment of suicide risk by this single BDI-II item is inadequate for identifying adolescents at risk for postsurgery suicidality. Finally, it is possible, yet unknown, whether participation in these studies impacted rates of STBs. All participants who endorsed suicidality at any timepoint received follow-up risk assessments and referrals via a licensed study psychologist.

Longer-term postsurgery outcome studies that utilize a controlled design and consider presurgical suicidality are needed and ongoing as part of the TeenView study series. This is of particular importance given adult data indicate suicide deaths typically occur beyond postsurgery Year 4,78 and national trends indicate suicide deaths disproportionately occur during young adulthood.8,26 Tracking STBs during this developmental period is critically important to defining patient care guidelines for this age group, for whom efficacious weight loss treatment options are urgently needed.

Highlights.

Surgical and nonsurgical groups were similar in suicidal behaviors across 4 years.

An at risk subgroup had a presurgical attempt history and poor psychosocial health.

Uniquely adolescent post-operative care guidelines are indicated.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of additional TeenView Study Group Co-Investigators and staff. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center: Faye Doland, BS, Ashley Morgenthal, BS, Taylor Howarth, BS, Sara Comstock, MA, Shelley Kirk, PhD, Michael Helmrath, MD, PhD; Texas Children’s Hospital: Margaret Callie Lee, MPH, David Allen, BS, Beth Garland, PhD, Carmen Mikhail, PhD, Mary L. Brandt, MD; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center: Ronette Blake, BS, Nermeen El Nokali, PhD, Silva Arslanian, MD; Children’s Hospital of Alabama-University of Alabama: Krishna Desai, MD, Amy Seay, PhD, Beverly Haynes, BSN, Carroll Harmon, MD, PhD; Nationwide Children’s Hospital Medical Center: Melissa Ginn, BS, Amy E. Baughcum, PhD, Marc P. Michalsky, MD; Teen-LABS Data Coordinating Center: Michelle Starkey Christian, Jennifer Andringa, BS, Carolyn Powers, RD, Rachel Akers, MPH.

Funding source: The TeenView ancillary studies (R01DK080020 and R01DA033415; PI: Zeller) were conducted in collaboration with the Teen-LABS Consortium. Teen-LABS was funded by cooperative agreements with the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), through grants: U01DK072493, UM1DK072493, and UM1DK095710 (University of Cincinnati). Dr. Kidwell’s effort was supported by an NIH postdoctoral training grant (T32 DK063929).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors have indicated they have no relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Financial Disclosure: Thomas H. Inge has served as a consultant for Standard Bariatrics, UpToDate, and Independent Medical Expert Consulting Services, all unrelated to this project. Anita P. Courcoulas has received research grants from Allurion Inc., unrelated to this project.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mitchell JE, Crosby R, de Zwaan M, et al. Possible risk factors for increased suicide following bariatric surgery. Obesity. 2013;21(4):665–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peterhansel C, Petroff D, Klinitzke G, Kersting A, Wagner B. Risk of completed suicide after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2013;14(5):369–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams TD, Mehta TS, Davidson LE, Hunt SC. All-cause and cause-specific mortality associated with bariatric surgery: A Review. Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 2015;17(12):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castaneda D, Popov VB, Wander P, Thompson CC. Risk of suicide and self-harm is increased after bariatric surgery-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2019;29(1):322–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes 12 years after gastric bypass. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1143–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Who Courcoulas A., why, and how? Suicide and harmful behaviors after bariatric surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;265(2):253–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Colpe L, Huang L, McKeon R. National trends in the prevalence of suicidal ideation and behavior among young adults and receipt of mental health care among suicidal young adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(1):20–27.e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miron O, Yu KH, Wilf-Miron R, Kohane IS. Suicide rates among adolescents and young adults in the United States, 2000–2017. JAMA. 2019;321(23):2362–2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruch DA, Sheftall AH, Schlagbaum P, Rausch J, Campo JV, Bridge JA. Trends in suicide among youth aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, 1975 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e193886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute of Mental Health. Suicide. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml Accessed December 10, 2018.

- 11.Eaton DK, Lowry R, Brener ND, Galuska DA, Crosby AE. Associations of body mass index and perceived weight with suicide ideation and suicide attempts among US High School Students. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(6):513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swahn MH, Reynolds MR, Tice M, Miranda-Pierangeli MC, Jones CR, Jones IR. Perceived overweight, BMI, and risk for suicide attempts: findings from the 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(3):292–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeller MH, Reiter-Purtill J, Jenkins TM, Ratcliff MB. Adolescent suicidal behavior across the excess weight status spectrum. Obesity. 2013;21(5):1039–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Suicide Disparity Details by Obesity Status 2009–2017. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data/disparities/summary/Chart/4810/19.1 Accessed February 1, 2019.

- 15.Gordon KH, King WC, White GE, et al. A longitudinal examination of suicide-related thoughts and behaviors among bariatric surgery patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(2):269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White GE, Courcoulas AP, King WC. Drug- and alcohol-related mortality risk after bariatric surgery: evidence from a 7-year prospective multicenter cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(7):1160–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duffecy J, Bleil ME, Labott SM, Browne A, Galvani C. Psychopathology in adolescents presenting for laparoscopic banding. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43(6):623–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McPhee J, Khlyavich Freidl E, Eicher J, et al. Suicidal Ideation and Behaviours Among Adolescents Receiving Bariatric Surgery: A Case-Control Study. European Eating Disorders Review. 2015;23(6):517–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarvholm K, Karlsson J, Olbers T, et al. Characteristics of adolescents with poor mental health after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(4):882–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zitsman JL, DiGiorgi MF, Fennoy I, Kopchinski JS, Sysko R, Devlin MJ. Adolescent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB): prospective results in 137 patients followed for 3 years. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(1):101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inge TH, Courcoulas AP, Jenkins TM, et al. Weight loss and health status 3 years after bariatric surgery in adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inge TH, Jenkins TM, Xanthakos SA, et al. Long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery in adolescents with severe obesity (FABS-5+): a prospective follow-up analysis. The lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2017;5(3):165–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inge TH, Courcoulas AP, Jenkins TM, et al. Five-year outcomes of gastric bypass in adolescents as compared with adults. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(22):2136–2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olbers T, Beamish AJ, Gronowitz E, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in adolescents with severe obesity (AMOS): a prospective, 5-year, Swedish nationwide study. The lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2017;5(3):174–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):300–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olfson M, Blanco C, Wall M, et al. National trends in suicide attempts among adults in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(11):1095–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pascal de Raykeer R, Hoertel N, Blanco C, et al. Effects of psychiatric disorders on suicide attempt: Similarities and differences between older and younger adults in a national cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunsaker SL, Garland BH, Rofey D, et al. A multisite 2-year follow-up of psychopathology prevalence, predictors, and correlates among adolescents who did or did not undergo weight loss surgery. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(2):142–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crow S, Eisenberg ME, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Suicidal behavior in adolescents: Relationship to weight status, weight control behaviors, and body dissatisfaction. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(1):82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown KL, LaRose JG, Mezuk B. The relationship between body mass index, binge eating disorder and suicidality. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Utzinger LM, Gowey MA, Zeller M, et al. Loss of control eating and eating disorders in adolescents before bariatric surgery. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49(10):947–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldschmidt AB, Khoury J, Jenkins TM, et al. Adolescent loss-of-control eating and weight loss maintenance after bariatric surgery. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1):e20171659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis L, Barnes AJ, Gross AC, Ryder JR, Shlafer RJ. Adverse childhood experiences and weight status among adolescents. J Pediatr. 2019;204:71–76 e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeller MH, Noll JG, Sarwer DB, et al. Child maltreatment and the adolescent patient with severe obesity: Implications for clinical care. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40(7): 640–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sutin AR, Robinson E, Daly M, Terracciano A. Perceived body discrimination and intentional self-harm and suicidal behavior in adolescence. Child Obes. 2018;14(8):528–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reiter-Purtill J, Gowey MA, Austin H, et al. Peer victimization in adolescents with severe obesity: The roles of self-worth and social support in associations with psychosocial adjustment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42(3):272–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeller MH, Inge TH, Modi AC, et al. Severe obesity and comorbid condition impact on the weight-related quality of life of the adolescent patient. J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):651–659 e654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mars B, Heron J, Klonsky ED, et al. What distinguishes adolescents with suicidal thoughts from those who have attempted suicide? A population-based birth cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2019;60(1):91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McManama O’Brien KH, Becker SJ, Spirito A, Simon V, Prinstein MJ. Differentiating adolescent suicide attempters from ideators: examining the interaction between depression severity and alcohol use. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(1):23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeller MH, Washington GA, Mitchell JE, et al. Alcohol use risk in adolescents 2 years after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(1):85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong SS, Zhou B, Goebert D, Hishinuma ES. The risk of adolescent suicide across patterns of drug use: a nationally representative study of high school students in the United States from 1999 to 2009. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2013;48(10):1611–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gowey MA, Reiter-Purtill J, Becnel J, et al. Weight-related correlates of psychological dysregulation in adolescent and young adult (AYA) females with severe obesity. Appetite. 2016;99:211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reynolds WM. Manual for the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reynolds JM. Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire: Professiional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reynolds WM. Psychometric characteristics of the Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire in college students. J Pers Assess. 1991;56(2):289–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. 2009; Available at http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/index.htm Accessed April 16, 2009.

- 48.Kolotkin RL, Zeller MH, Modi AC, et al. Assessing weight-related quality of life in adolescents. Obesity. 2006;14(3):448–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, Williams GR. Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9:102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Achenbach TMR, L.A.. Manual for the ASEBA Adult Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spitzer RL, Yanovski SZ, Marcus MD. The Questionnaire of Eating and Weight Patterns-Revised (QEWP-R, 1993). (Available from the New York State Psychiaric Institute, 722 West 168th Street, New York, NY 10032: ). 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. J Clin Child Psychol. 2001;30(4):479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(2):169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mezzich AC, Tarter RE, Giancola PR, Kirisci L. The Dysregulation Inventory: A new scale to assess the risk for substance use disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Use. 2001;10(4):35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidleines for use in primary care. Vol No. 89.4 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knight JR, Sherritt L, Harris SK, Gates EC, Chang G. Validity of brief alcohol screening tests among adolescents: a comparison of the AUDIT, POSIT, CAGE, and CRAFFT. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(1):67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnston L, O’Malley P, Bachman J, Schulenberg J. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2010. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Piscopo K, Lipari RN, Cooney J, & Glasheen C Suicidal thoughts and behavior among adults: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Data Review 2016; http:www.samhsa.gov/data/ Accessed 02/23/18.

- 61.Bhatti JA, Nathens AB, Thiruchelvam D, Grantcharov T, Goldstein BI, Redelmeier DA. Self-harm emergencies after bariatric surgery: A population-based cohort study. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(3):226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Borges G, Angst J, Nock MK, Ruscio AM, Kessler RC. Risk factors for the incidence and persistence of suicide-related outcomes: A 10-year follow-up study using the National Comorbidity Surveys. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;105(1–3):25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bostwick JM, Pabbati C, Geske JR, McKean AJ. Suicide Attempt as a Risk Factor for Completed Suicide: Even More Lethal Than We Knew. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;173(11):1094–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Andriessen K, Rahman B, Draper B, Dudley M, Mitchell PB. Prevalence of exposure to suicide: A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2017;88:113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ivezaj V, Benoit SC, Davis J, et al. Changes in alcohol use after metabolic and bariatric surgery: Predictors and mechanisms. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(9):85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tindle HA, Omalu B, Courcoulas A, Marcus M, Hammers J, Kuller LH. Risk of suicide after long-term follow-up from bariatric surgery. Am J Med. 2010;123(11):1036–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spiller HA, Ackerman JP, Spiller NE, Casavant MJ. Sex- and age-specific increases in suicide attempts by self-poisoning in the United States among youth and young adults from 2000 to 2018. J Pediatr. 2019;210:201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rockett IR, Lilly CL, Jia H, et al. Self-injury mortality in the United States in the early 21st Century: A comparison with proximally ranked diseases. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(10):1072–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pratt JSA, Browne A, Browne NT, et al. ASMBS Pediatric Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Guidelines, 2018. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(7):882–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Austin H, Smith K, Ward WL. Psychological assessment of the adolescent bariatric surgery candidate. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(3):474–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sysko R, Zandberg LJ, Devlin MJ, Annunziato RA, Zitsman JL, Walsh BT. Mental health evaluations for adolescents prior to bariatric surgery: A review of existing practices and a specific example of assessment srocedures. Clinical Obesity. 2013;3(3–4):62–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Husky MM, Olfson M, He JP, Nock MK, Swanson SA, Merikangas KR. Twelve-month suicidal symptoms and use of services among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(10):989–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Horowitz LM, Bridge JA, Teach SJ, et al. Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ): a brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166(12):1170–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brahmbhatt K, Kurtz BP, Afzal KI, et al. Suicide risk screening in pediatric hospitals: Clinical pathways to address a global health crisis. Psychosomatics. 2019;60(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Griggs CL, Perez NP Jr., Goldstone RN, et al. National Trends in the use of metabolic and bariatric Surgery among pediatric patients with severe obesity. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(12):1191–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Burstein B, Agostino H, Greenfield B. Suicidal attempts and adeation among children and adolescents in US emergency departments, 2007–2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(6):598–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, et al. Hospitalization for suicide adeation or attempt: 2008–2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Neovius M, Bruze G, Jacobson P, et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: results from two matched cohort studies. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2018;6(3):197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]