Abstract

Background

Double checking medication administration in hospitals is often standard practice, particularly for high-risk drugs, yet its effectiveness in reducing medication administration errors (MAEs) and improving patient outcomes remains unclear. We conducted a systematic review of studies evaluating evidence of the effectiveness of double checking to reduce MAEs.

Methods

Five databases (PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Ovid@Journals, OpenGrey) were searched for studies evaluating the use and effectiveness of double checking on reducing medication administration errors in a hospital setting. Included studies were required to report any of three outcome measures: an effect estimate such as a risk ratio or risk difference representing the association between double checking and MAEs, or between double checking and patient harm; or a rate representing adherence to the hospital’s double checking policy.

Results

Thirteen studies were identified, including 10 studies using an observational study design, two randomised controlled trials and one randomised trial in a simulated setting. Studies included both paediatric and adult inpatient populations and varied considerably in quality. Among three good quality studies, only one showed a significant association between double checking and a reduction in MAEs, another showed no association, and the third study reported only adherence rates. No studies investigated changes in medication-related harm associated with double checking. Reported double checking adherence rates ranged from 52% to 97% of administrations. Only three studies reported if and how independent and primed double checking were differentiated.

Conclusion

There is insufficient evidence that double versus single checking of medication administration is associated with lower rates of MAEs or reduced harm. Most comparative studies fail to define or investigate the level of adherence to independent double checking, further limiting conclusions regarding effectiveness in error prevention. Higher-quality studies are needed to determine if, and in what context (eg, drug type, setting), double checking produces sufficient benefits in patient safety to warrant the considerable resources required.

Keywords: health services research; medical error, measurement/epidemiology; medication safety; patient safety; human factors

Introduction

Medication safety continues to present a serious challenge in hospitals. Processing medications involves multiple steps and individuals. Medication errors can occur during different stages, with a high frequency occurring during administration.1 2 Medication administration errors (MAEs) are reported to occur in 20% to 25% of dose administrations.3 4 While prescribing and dispensing errors can be intercepted as a medication order proceeds towards patient administration,5 interventions to reduce errors during administration are especially critical as it is the final step before a patient receives a drug.5 Various strategies have been developed and implemented in clinical practice to minimise MAEs.

The process of double checking is adopted as standard safety practice in many hospitals, as well as in other high-hazard industries such as aviation and nuclear power.6

Double checking medication administration involves two individuals verifying the same information, while single checking involves a single individual verifying the information.

The potential safety benefits of double checking rely on two key factors: two separate individuals verifying key information and independent verification. Two individuals should result in fewer errors by minimising endogenous errors that arise from one individual and are therefore independent from errors that may arise in another individual.7 Exogenous errors that arise from external factors, such as illegible text, are potentially reduced through independent double checking when verification is performed without one checker priming the other with information to be verified.7–9 Several studies have, however, demonstrated that organisational double checking policies often differ in their level of detail of how the double-checking process should be conducted, contributing to variation in the application by nurses.10–12 Some organisations require double checking for all medications while others only for high-risk medications such as opioids, chemotherapeutic agents and intravenous drugs. Significant resources are required, given the process requires two individuals instead of one.

Evidence that the process is effective in reducing errors is central to ensuring that this ingrained policy is justified in terms of resource use and workflow disruptions.13 14 Double checking has been implemented in hospitals based on an assumption that it will result in fewer MAEs, and at times as a response to incidents when single checking was assessed to have contributed to a serious error.15–19 However, its effectiveness in reducing MAEs and improving patient outcomes remains unclear. Much previous literature on double checking involves qualitative studies. A previous systematic review of studies published prior to October 2010 investigated double checking during medication dispensing and administration and found only three quantitative studies which provided insufficient evidence to assess the effectiveness of double checking in error reduction.20 Serious review of this safety procedure is unable to proceed without a sound evidence-base. Thus, we performed a systematic review to examine contemporary evidence of the effectiveness of double checking to reduce medication administration errors and associated harm to identify both the strength of that evidence and where future research needs to focus.

Methods

Search strategy

Two reviewers (AKK and C-SSM) independently performed each step of the literature search. A Boolean search strategy (online supplementary eTables 1 and 2) was used to search for relevant articles in the MEDLINE, Embase, Ovid@Journals and CINAHL databases. Grey literature was searched using the OpenGrey database (online supplementary eTable 3). Articles were searched from the inception of each database through October 2018. Reference lists of all articles included in the full-text review and review papers20 21 were also searched for relevant articles. Each reviewer independently screened the title and abstract to first identify relevant articles. Next, the full text of each article was independently screened. After each stage, agreement on included studies was reached through discussion. This review followed PRISMA guidelines for the reporting of systematic reviews.22

bmjqs-2019-009552supp001.pdf (74.4KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria

For a study to be included, it had to evaluate the use and/or effectiveness of the double checking of medication administration within a hospital setting and report at least one of the following quantitative measures: (1) an effect estimate such as a risk ratio or risk difference representing the association between double checking (compared with single checking) and MAEs; (2) an analogous effect estimate for the outcome of patient harm. As the effectiveness of double checking can depend in part on the extent to which nurses adhere to the double checking policy, studies were also included if they reported a rate of adherence to double checking. Studies using either an observational study design or randomised controlled trial (RCT) design were included. Studies using an observational study design are non-experimental studies that do not randomise an intervention, which in this instance is the double-checking process. The observational study design categorisation is distinguished from the method of ‘direct observation’ which is the use of observers to collect information during a study. Studies involving administrations of all medication types or select groups of medications were included as were those involving adult and/or paediatric populations. Only English-language studies published in peer-reviewed journals were included; abstracts and case studies were excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction was performed by two reviewers (AKK and C-SSM) using a standardised extraction form. Abstracted variables were used to characterise studies and assess study quality. Variables included first author name, year of publication, country of study, years of data collection, study design, patient population, sample size and types of medications studied. If medication errors were assessed, the types of medications and errors, as well as the method of assessing errors were recorded. Variables specific to the double-checking process included the definition of double checking used, how double checking was measured (eg, through self-report or direct observation) and the policy of double checking at the participating institutions (ie, when double checking was required). Effect estimates for the association between double checking and MAEs or harm, along with corresponding p values and/or CIs, as well as double checking adherence rates were recorded. For one study,23 error-free medication administration rates were transformed into error rates for consistency with other studies. Study quality was measured using the assessment tools provided by the National Institutes of Health,24 assigning each study a rating of ‘poor’, ‘fair’ or ‘good’. For RCTs, the Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies was used. For studies using an observational study design, the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies was used. The tools measured study characteristics specific to the study type (eg, adequate randomisation for trials) as well as those common to both study types (eg, validity of the methods used to measure the outcomes of MAEs and double checking). All studies rated as good quality were required to have used direct observation to measure both MAEs and double checking.

Results

Study selection

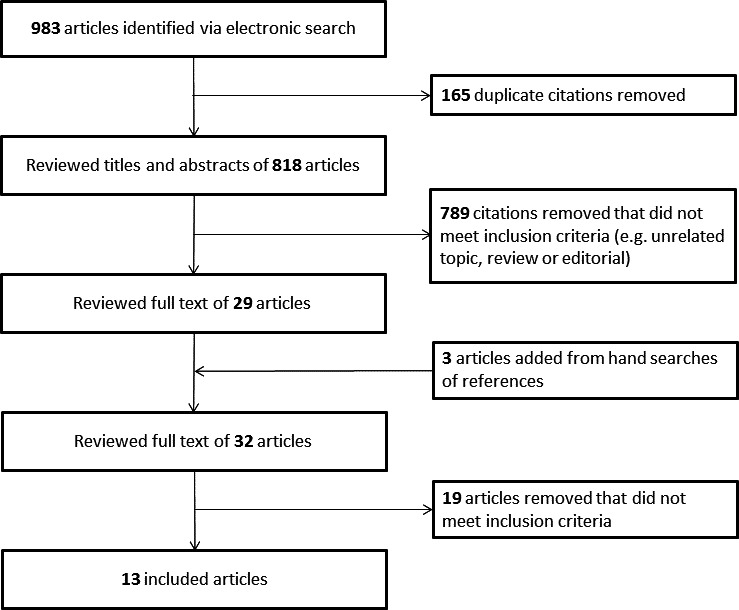

The study selection process is illustrated in figure 1. A total of 983 articles were retrieved from all databases. After removal of 165 duplicate articles, 818 unique articles remained for the title and abstract review. A further 789 articles were removed after title and abstract review as they did not meet inclusion criteria. From the resulting 29 articles, an additional three articles were added from hand searches of references, resulting in 32 articles. Nineteen articles were excluded during full-text review since they did not report any measure of association between double checking and MAEs, or double checking adherence rate. Thirteen articles were included in the final review, which comprised five articles reporting the association between double checking and MAEs,16 23 25–27 six articles reporting adherence rates28–33 and two articles reporting both measures.19 34 No studies assessed patient harm as an outcome.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study selection.

Study characteristics

The studies in the final review included 10 studies using an observational study design,19 26–34 two RCTs16 23 and one RCT conducted in a simulated setting.25 Studies using an observational study design are described in table 1 and RCTs in table 2. Seven studies were conducted among adult patients,16 23 26 27 31 32 34 one used a simulated adult patient25 and five involved paediatric patients.19 28–30 33 The majority of studies investigated all types of medications administered in the hospital, while three investigated only specific parenteral drugs.19 23 32 One study assessed only oral, inhaled and topical preparations.16 Seven studies investigated medication safety as a primary aim26 29–34 and double checking as a secondary aim.

Table 1.

Studies using an observational study design investigating double checking of medication administration

| Study | Country | Sample size/study duration | Setting | Method of measuring double checking | Method of measuring errors | Findings | Study quality |

| Jarman 2002*27 | Australia | 14 months | Inpatient units, operating suites, birthing suite and ED at a 400-bed academic tertiary care hospital | None (before and after study of change in policy) | Incident report forms |

|

Poor |

| Manias 200531 | Australia | 175 administrations to 47 patients over 2 months | Metropolitan academic teaching hospital | Direct observation | – |

|

Fair |

| Conroy 200730 | UK | 752 administrations to 253 patients over 6 weeks | Medical and surgical wards, PICU, NICU, ED in a 92-bed paediatric hospital | Direct observation | Direct observation |

|

Fair |

| Alsulami 201428 | UK | 2000 administrations to 876 patients over 4 months | Medical and surgical wards, PICU, NICU in a paediatric hospital | Direct observation | Direct observation |

|

Good |

| Bulbul 201429 | Turkey | 98 nurses | Paediatric emergency, paediatric and neonatology, paediatric surgery wards in two teaching and research hospitals | Self-report | Self-report |

|

Poor |

| Schilp 201432 | Netherlands | 2154 administrations of intravenous drugs over 1 year | ICU, internal medicine, general surgery and other departments administering intravenous drugs in 19 hospitals (2 academic, 6 tertiary teaching, 11 general) | Direct observation | – |

|

Fair |

| Härkänen 201534 | Finland | 1058 administrations to 122 patients over 2 months | Medical and surgical wards in an 800-bed academic hospital | Direct observation | Direct observation, medical records |

|

Good |

| Young 201533 | USA | 60 administrations to 47 paediatric and 10 adult patients over 24 days | 198-bed paediatric inpatient hospital | Direct observation | Direct observation |

|

Poor |

| Cochran 201626 | USA | 6497 administrations to 1374 patients | 12 rural hospitals | Direct observation | Direct observation, medical records |

|

Poor |

| Subramanyam 201619 | USA | 1473 intravenous infusions over 1 year | Paediatric patients undergoing radiological imaging at a tertiary academic paediatric hospital | Self-report | Self-report |

|

Poor |

*This study used a before-and-after design. All other studies were observational cohort studies.

ED, emergency department; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit.

Table 2.

Randomised controlled trials investigating double checking of medication administration

| Study | Country | Sample size/study duration | Setting | Method of measuring errors | Findings | Study quality |

| Kruse 199216 | Australia | 129 234 oral, inhaled or topical administrations over 46 weeks | 3 wards of a geriatric assessment and rehabilitation unit | Chart review data supplemented by incident reports |

|

Fair |

| Modic 201623 | USA | 5238 administrations of subcutaneous insulin to 266 patients | Patients with diabetes at a 1400-bed quaternary care hospital | In double check group, anonymous self-report; in single check group, review of electronic medical records |

|

Fair |

| Douglass 201825 | USA | 43 pairs of ED and ICU nurses | Simulated adult patient in a medical education centre | Direct observation |

|

Good |

ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

Study quality varied, and many studies were underpowered to provide meaningful results regarding the association between double checking and MAEs. Three studies had small study populations,25 29 33 and five studies relied partially or completely on self-report to measure medication errors, likely resulting in a large under-ascertainment of actual error rates.16 19 23 27 Furthermore, one of these studies used self-report only for double-checked administrations and medical record review for single-checked administrations, possibly biasing results towards a positive association between double checking and a reduced medication error rate.23 Two studies using an observational study design reported very low error rates (1.2% overall26; four errors in a 7-month double checking period compared with five in a 7-month single checking period27), making it difficult to adequately assess any association between double checking and medication errors.

Among studies using an observational study design, the majority measured double checking through direct observation26 28 30–34 and two used self-report of double checking.19 29 One study did not measure double checking but employed a before-and-after design, assessing MAEs in the hospital before and after implementation of a double checking policy.27 Among the three RCTs, one study used direct observation to measure adherence to double checking,25 while the other two did not measure adherence.16 23

The majority of studies provided few details on what steps comprised the double-checking procedure. Only two studies reported the individual steps in the medication administration process which required double checking.23 28 In addition, only three studies25 30 34 reported if and how independent and primed double checking were differentiated. Most hospitals required double checking based on nurse qualifications and administration of high-risk drugs,16 25 27 30 31 with one study requiring double checking for all drugs.28

Double checking and MAEs

Three RCTs (table 2) evaluated the possible effect of double checked compared with single-checked administrations on MAEs as the primary objective.16 23 25 Two of these studies were conducted in a hospital,16 23 while the third was a simulation trial.25 Although results from two of the three studies reported a significant association between double checking and a reduction in medication errors, methodological concerns in each study limited the validity of the findings. In a fair-quality RCT16 published in 1992, three wards of a geriatric assessment and rehabilitation unit were randomised in a cross-over design to have non-restricted drugs either (1) double checked then single checked, (2) single checked then double checked, or (3) always double checked, as a control. A total of 129 234 oral, inhaled or topical administrations were evaluated over 46 weeks. MAEs were recorded from chart review and incident reports, depending on the type of error. The rate of errors was significantly lower for double-checked compared with single-checked administrations (2.12 (1.69 to 2.55) vs 2.98 (2.45 to 3.51) per 1000 administrations). Findings may have been affected by an observer effect from study participation, as error rates significantly decreased in all wards over the course of the study. Moreover, results were not adjusted for correlated administrations and some types of errors were likely under-ascertained as they relied solely on voluntary incident reports.

In a parallel RCT conducted at a quaternary care hospital, 5238 subcutaneous insulin injections were administered to 266 adult patients with diabetes across two groups23: one group required double checking and a second group was subject to standard hospital policy that did not require double checking. Five medical and surgical units were randomised to one of the two groups. In multivariate regression, double checking was significantly associated with a lower odds of any type of error (OR 0.72 (0.64 to 0.81)), but this association was no longer significant after adjusting for nurse to account for multiple administrations by the same nurse (OR 0.85 (0.59 to 1.21)). However, there was a significant methodological flaw in the study. To record MAEs, anonymous self-reporting was used for double checking versus chart review for single checking. Study quality was rated as fair, as under-ascertainment of errors through self-report likely biased the results in favour of the double checking group.

In a good-quality experimental trial involving care of a simulated adult patient, 43 pairs of nurses were randomised to a setting in which they would administer either a drug requiring a double check according to hospital policy (insulin) or a single check drug (midazolam).25 A wrong drug and wrong dose error were both introduced as part of the experimental intervention and nurses were directly observed to see if the errors were intercepted. In the single check group, 9% of nurses detected the dose error compared with 33% in the double check group (OR 5.0 (0.90 to 27.74)). For the wrong drug error, 54% of nurses in the single check group detected the error, compared with 100% in the double check group (OR 19.9 (1.0 to 408.5)). A limitation of this study is the use of different drugs in each scenario, as it is possible that nurses may be more likely to double check insulin compared with midazolam regardless of hospital policy.

Four studies using an observational study design provided results for the association between double checking and medication errors. In a good-quality study of 122 medical and surgical inpatients at an academic hospital, double checking was directly observed to occur in 81% (856/1058) of administrations.34 Details about medication administrations were recorded by two independent nurse observers using a structured form, and medication errors were identified by comparing information on the forms with medication information in patients’ electronic records. Multivariate regression showed that double checking was significantly associated with a lower odds of any medication error (OR 0.44 (0.27 to 0.72)). A further study, in a large academic hospital, reported medication error rates before and after the introduction of a double checking policy.27 Little could be inferred from this study as the number of errors reported, based on incident reports, was very low.

One study conducted in 12 rural hospitals reported only the numbers of directly observed combined preparation and administration errors that occurred and reached patients, when different processes were in place. Nine out of 10 errors reached patients when double checks were used, 16 out of 23 during single checks and four out of 12 during bar code administration.26 In one study of the introduction of enforced double checking for paediatric patients undergoing radiological imaging, reported rates of intercepted MAEs decreased from 4 to 1 per month, but study conclusions were limited due to the small number of MAEs.19 Six studies using an observational study design provided adherence rates but did not test for an association between double checking and MAEs.28–33

Adherence to double checking

Reported adherence rates varied from 52% to 97% of administrations in studies of adult patients.31 32 34 Among studies of paediatric patients, methods of reporting adherence varied and ranged from 64% of nurses,29 84% of patients,30 and 75% to 90% of administrations.19 33 One study of 2000 directly observed administrations in a small paediatric hospital reported adherence rates for individual steps of the administration process. Adherence was 90% or greater for 11 of 15 steps, and lowest for the actual administration to the patient (83%), rate of intravenous bolus (71%), labelling of flush syringes (67%) and dose calculation (30%).28 The RCT conducted in a simulated setting study found all 21 nurses in the double check group used a double check as instructed.25

Discussion

There is little compelling evidence from studies undertaken in hospitals that double checking of medications is associated with a significant reduction in MAEs. Only three good-quality studies were found, among which two reported on the association between double checking and MAEs.25 34 Of these, one reported that double checking was significantly associated with lower rates of MAEs compared with single checking34 while the other reported no significant association.25 Of particular concern was the use of self-reports or incident report data to measure MAEs in 5 of 13 studies reviewed, given such measures have been demonstrated to significantly underestimate the true error rate.35 While we did not identify any studies with quantifiable evidence regarding the association between double checking and patient harm, we can hypothesise as to the potential effects. Since the proportion of MAEs that result in actual harm is reported to be approximately 1% to 4%,34 36 even a large risk ratio in favour of double checking conveying a protective effect may not result in a substantial reduction in harm. An important consideration in assessing the value of the double-checking process is its potential value in preventing rare but catastrophic errors. Evidence of such occurrences is difficult to identify as cases are most likely to rely on reported ‘near-miss’ incidents or case reports, which were not included in this review. Large, robust trials measuring both the frequency and severity of errors identified and prevented during the double-checking process, as well as potential and actual outcomes of errors are required to more adequately address the question of the effectiveness of the double-checking process.

A lack of evidence was also apparent in relation to the fidelity of the double-checking processes applied in the reviewed studies. Details of how compliance was measured was rarely reported. For example, a key component of the double-checking process is the independence of the check, yet few studies reported on this measure. Thus, the question arises as to whether the lack of association between double checking and outcomes is due to poor fidelity of the intervention (ie, double checking is rarely performed in a rigorous, complete way) or due to a lack of effect. Qualitative studies have highlighted factors which may influence the fidelity and effectiveness of double checking, such as the automatic nature of the task which may decrease one’s attention, diffusion of responsibility between checkers, and deference to authority when a junior nurse may not correct an error made by a more senior nurse.13 14 Examples of the latter were directly observed in one of the reviewed studies conducted in a simulated setting.25 Future studies require closer attention to the details of the double-checking process used, in particular the extent to which checks are performed independently and whether all steps in the process are completed as specified.

Defining and implementing double checking

There is considerable variation and often a lack of clarity about how the double check should be performed.13 14 37 38 Evidence from qualitative studies and cognitive theory suggest a clear and consistent process of independent double checking is desirable,9 13 but few studies report details of what the double-checking process actually entails. Three of the reviewed studies listed the specific items to be double checked23 28 32 but provided no further detail on how to perform the double check. One study provided a flow diagram of the administration process that included which items were to be double checked.19 Other studies of double checking have reported the process of double checking to range from no well-defined procedure14 to standardised checklists8 or a flow chart designed by a human factors team.39 While certain aspects of a checklist, such as step-by-step instructions, compared with abstract general reminders, have been shown to be more effective in detecting errors,8 other evidence remains scant as to which methods of double checking may be most effective.

In addition, most studies investigating double checking did not explicitly differentiate between independent and primed double checking. Two studies specifically described the double checking performed as independent28 34 and one provided counts for both independent and primed double checks.25 However, neither of these studies provided rates of MAEs comparing independent versus primed double checking. Independent double checking is preferred since if the checker is primed, an error may not be detected due to confirmation bias.8 Supporting this point, in the simulation study, both the dosage and wrong drug errors were discovered more frequently during independent double checks than during primed double checks.25 It is possible that double checking is never truly independent in real-world settings regardless of how the double-checking process is defined. For example, since the checker knows whose work they are checking, confidence in the correct medication administration can become biased based on the other nurse’s experience and qualifications. Moreover, psychological theory suggests that any level of priming between the two checks can substantially decrease the probability of the checker detecting an error.40

Even if the double-checking process is well defined, nurses may not be clear about how to put it into action.11 38 Only two studies provided detail on how double checking was implemented. One study, aiming to reduce intravenous infusion errors in a paediatric hospital, used multiple methods including staff education, visual aids, reminders and a modification to the electronic medical record system to properly record double checking.19 Another study in a paediatric hospital aimed to reduce MAEs through multiple safety practices, including double checking, by training nurses in a simulated clinical environment.41 While there is a small number of examples, a well-defined process of double checking and a structured, formal method of training, along with feedback should be employed for effective policy implementation. Despite an absence of well-defined or reported definitions of double checking, reported adherence rates were relatively high across studies, ranging from 52% to 97%. This may be partly a reflection of nurses’ belief that the process is effective and of value to perform.

Limitations

This review includes potential limitations. First, non–English-language studies were not searched, which may lead to publication bias. As only three of the 14 reviewed studies were rated as good quality, methodological limitations can also affect the collective findings. For example, five studies partially or completely relied on self-report to measure MAEs. Self-report likely resulted in under-ascertainment of MAEs, limiting the studies’ findings. Decreased power may arise if under ascertainment was equal across all administrations, or bias, if under-ascertainment was systematically different across double-checked and single-checked administrations.23 Many studies also had insufficient sample sizes resulting in inadequate power to evaluate the association between double checking and medication errors. In addition, many studies only conducted basic bivariate analysis which may not properly account for potential confounding and other biases. Reviewed studies were also heterogeneous in their statistical analyses and reporting methods, making quantitative comparisons such as a meta-analysis infeasible. Lastly, inter-reviewer reliability was not formally estimated since consensus between two reviewers was reached. Conversely, a particular strength of this review is that it provides much updated evidence on the effectiveness of double checking, reviewing an additional 12 quantitative studies published since a prior systematic review.20

Conclusions

Double checking presents at face value as a logical safety precaution which has been embedded in nursing practice for decades. However, as this review reveals, there is no solid evidence-base to support its use. Our review of the evidence shows both an absence of good-quality studies, and generally an absence of effectiveness in reducing medication error rates and patient harm. In most studies, the double-checking process tested was ill-defined and the fidelity of the double-checking process left un-investigated. Given the extent to which it is embedded as part of routine nursing practice, and the considerable costs involved, there would appear to be a compelling reason to establish a sound evidence-base for its ongoing use and to inform decisions about when and how it might be most effective to improve medication safety. Higher-quality studies addressing the limitations of previous studies are needed including the measurement of robust outcome measures that do not rely on self-reports of medication error rates. Current evidence is insufficient to make recommendations about how, if or when double checking should be performed in hospitals in order to best improve safety. Even if double checking is indeed an ineffective means of improving patient safety, it can be very difficult to de-implement such a policy with likely resistance to changes11 42 as well as potential legal ramifications if serious errors subsequently occur.

Many hospitals are increasing the use of information technology to facilitate the medication administration process, and the ability for two nurses to sign off as part of the double-checking process has become an essential requirement in these systems. As such, their use may further increase the time taken for the double-checking process, as both nurses need to log onto the system, rather than co-signing a paper chart. The introduction of bar-coding may negate the need for two individuals to check some steps of the process, but as several studies have identified, workarounds and inconsistency in the way bar-coding technology is used in practice often jeopardises its effectiveness.43 Implementation of significant work flow changes, associated with the introduction of new technologies, however can be a useful impetus to examine work practices and provide an opportunity to re-consider long-held practices, informed by evidence. Thus, even with the introduction of potentially helpful technology, there remains a need for high-quality research to address fundamental questions about when and where double checking, either using humans or technology, is beneficial to patient safety outcomes.

Footnotes

Contributors: AKK was responsible for the study design, literature search, data extraction, study quality assessment and manuscript preparation. C-SSM was responsible for the literature search, data extraction and study quality assessment. LL and JIW contributed to the study design and manuscript preparation. TB contributed to manuscript preparation.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement statement: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information.

References

- 1. Ruano M, Villamañán E, Pérez E, et al. New technologies as a strategy to decrease medication errors: how do they affect adults and children differently? World J Pediatr 2016;12:28–34. 10.1007/s12519-015-0067-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller MR, Robinson KA, Lubomski LH, et al. Medication errors in paediatric care: a systematic review of epidemiology and an evaluation of evidence supporting reduction strategy recommendations. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:116–26. 10.1136/qshc.2006.019950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Westbrook JI, Woods A, Rob MI, et al. Association of interruptions with an increased risk and severity of medication administration errors. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:683–90. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hayes C, Jackson D, Davidson PM, et al. Medication errors in hospitals: a literature review of disruptions to nursing practice during medication administration. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:3063–76. 10.1111/jocn.12944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Noguchi C, Sakuma M, Ohta Y, et al. Prevention of medication errors in hospitalized patients: the Japan Adverse Drug Events Study. Drug Saf 2016;39:1129–37. 10.1007/s40264-016-0458-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spath PL. Error reduction in health care: a systems approach to improving patient safety. Wiley, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seki J, Turner L. Medication safety alerts. Can J Hosp Pharm 2003;56:97–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8. White RE, Trbovich PL, Easty AC, et al. Checking it twice: an evaluation of checklists for detecting medication errors at the bedside using a chemotherapy model. BMJ Qual Saf 2010;19:562–7. 10.1136/qshc.2009.032862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Winters BD, Gurses AP, Lehmann H, et al. Clinical review: Checklists—translating evidence into practice. Crit Care 2009;13 10.1186/cc7792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fossum M, Hughes L, Manias E, et al. Comparison of medication policies to guide nursing practice across seven Victorian health services. Aust Health Review 2016;40:526–32. 10.1071/AH15202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schwappach DLB, Pfeiffer Y, Taxis K. Medication double-checking procedures in clinical practice: a cross-sectional survey of oncology nurses’ experiences. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011394 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Conroy S, Davar Z, Jones S. Use of checking systems in medicines administration with children and young people. Nurs Child Young People 2012;24:20–4. 10.7748/ncyp.24.3.20.s25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Armitage G. Double checking medicines: defence against error or contributory factor? J Eval Clin Pract 2008;14:513–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00907.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dickinson A, McCall E, Twomey B, et al. Paediatric nurses’ understanding of the process and procedure of double-checking medications. J Clin Nurs 2010;19:728–35. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dobish R, Shultz J, Neilson S, et al. Worksheets with embedded checklists support IV chemotherapy safer practice. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2016;22:142–50. 10.1177/1078155214556009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kruse H, Johnson A, O'Connell D, et al. Administering non-restricted medications in hospital: the implications and cost of using two nurses. Aust Clin Rev 1992;12:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Monroe PS, Heck WD, Lavsa SM. Changes to medication-use processes after overdose of U-500 regular insulin. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2012;69:2089–93. 10.2146/ajhp110628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Henry TR, Azuma L, Shaban HM. Learning and process improvement after a sentinel event. Hosp Pharm 1999;34:839–44. 10.1177/001857879903400710 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Subramanyam R, Mahmoud M, Buck D, et al. Infusion medication error reduction by two-person verification: a quality improvement initiative. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20154413 10.1542/peds.2015-4413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alsulami Z, Conroy S, Choonara I. Double checking the administration of medicines: what is the evidence? A systematic review. Arch Dis Child 2012;97:833–7. 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kellett P, Gottwald M. Double-checking high-risk medications in acute settings: a safer process. Nurs Manage 2015;21:16–22. 10.7748/nm.21.9.16.e1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Modic MB, Albert NM, Sun Z, et al. Does an insulin procedure improve patient safety? JONA 2016;46:154–60. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Study quality assessment tools [Accessed Nov 2018].

- 25. Douglass AM, Elder J, Watson R, et al. A randomized controlled trial on the effect of a double check on the detection of medication errors. Ann Emerg Med 2018;71:74–82. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cochran GL, Barrett RS, Horn SD. Comparison of medication safety systems in critical access hospitals: combined analysis of two studies. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2016;73:1167–73. 10.2146/ajhp150760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jarman H, Jacobs E, Zielinski V. Medication study supports registered nurses’ competence for single checking. Int J Nurs Pract 2002;8:330–5. 10.1046/j.1440-172X.2002.00387.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alsulami Z, Choonara I, Conroy S. Paediatric nurses’ adherence to the double-checking process during medication administration in a children's hospital: an observational study. J Adv Nurs 2014;70:1404–13. 10.1111/jan.12303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bulbul A, Kunt A, Selalmaz M, et al. Assessment of knowledge of pediatric nurses related with drug administration and preparation. Turk Arch Ped 2015;49:333–9. 10.5152/tpa.2014.1751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Conroy S, Appleby K, Bostock D, et al. Medication errors in a children's hospital. Paediatr Perinat Drug Ther 2007;8:18–25. 10.1185/146300907X167790 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Manias E, Aitken R, Dunning T. How graduate nurses use protocols to manage patients’ medications. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:935–44. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schilp J, Boot S, de Blok C, et al. Protocol compliance of administering parenteral medication in Dutch hospitals: an evaluation and cost estimation of the implementation. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005232 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Young K, Cochran K. Ensuring safe medication administration through direct observation. Quality in Primary Care 2015;23:167–73. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Härkänen M, Ahonen J, Kervinen M, et al. The factors associated with medication errors in adult medical and surgical inpatients: a direct observation approach with medication record reviews. Scand J Caring Sci 2015;29:297–306. 10.1111/scs.12163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Westbrook JI, Li L, Lehnbom EC, et al. What are incident reports telling us? A comparative study at two Australian hospitals of medication errors identified at audit, detected by staff and reported to an incident system. Int J Qual Health Care 2015;27:1–9. 10.1093/intqhc/mzu098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gates PJ, Meyerson SA, Baysari MT, et al. Preventable adverse drug events among inpatients: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2018;142:e20180805 10.1542/peds.2018-0805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gill F, Corkish V, Robertson J, et al. An exploration of pediatric nurses’ compliance with a medication checking and administration protocol. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2012;17:136–46. 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2012.00331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hewitt T, Chreim S, Forster A. Double checking: a second look. J Eval Clin Pract 2016;22:267–74. 10.1111/jep.12468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Evley R, Russell J, Mathew D, et al. Confirming the drugs administered during anaesthesia: a feasibility study in the pilot National Health Service sites, UK. Br J Anaesth 2010;105:289–96. 10.1093/bja/aeq194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Swain AD. Handbook of human reliability analysis with emphasis on nuclear power plant applications: final report, ed. Sandia National Laboratories. Vol. 80. 662 Albuquereque, New Mexico and Livermore, California, USA: The Commission, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hebbar KB, Colman N, Williams L, et al. A quality initiative: a system-wide reduction in serious medication events through targeted simulation training. Simul Healthc 2018;13:324–30. 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. O'Connell B, Crawford S, Tull A, et al. Nurses' attitudes to single checking medications: before and after its use. Int J Nurs Pract 2007;13:377–82. 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2007.00653.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Westbrook JI, Baysari M. Technological approaches for medication administration : Tully MP, Franklin BD, Safety in medication use. London, UK: Taylor and Francis, 2016: 229–37. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjqs-2019-009552supp001.pdf (74.4KB, pdf)