Abstract

Background

Due to the pandemic, there is a significant interest in the therapeutic resources linked to TCIM to support potentially therapeutic research and intervention in the management of Coronavirus - 19 (COVID-19). At the date of this evidence map´s publication, there is no evidence of specific treatments for COVID-19. This map organizes information about symptoms management (especially on dimensions related to mental health and mild viral respiratory infections, as well as immune system strengthening and antiviral activity).

Method

This evidence map applies methodology developed by Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information based on the 3iE evidence gap map. A search was performed in the Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine Virtual Health Library and PubMed, using the MeSH and DeCS terms for respiratory viral diseases associated with epidemics, COVID-19 symptoms, relevant mental health topics, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions related to TCIM.

Results

For the map, 126 systematic reviews and controlled clinical studies were characterized, distributed in a matrix with 62 interventions (18 phytotherapy, 9 mind-body therapies, 11 traditional Chinese medicine, 7 homeopathic and anthroposophic dynamized medicines and 17 supplements), and 67 outcomes (14 immunological response, 23 mental health, 25 complementary clinical management of the infection and 5 other).

Conclusion

The map presents an overview of possible TCIM contributions to various dimensions of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in the field of mental health, and it is directed to researchers and health professionals specialized in TCIM. Most of the antiviral activity outcomes described in this map refers to respiratory viruses in general, and not specifically to SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome CoronaVirus 2). This information may be useful to guide new research, but not necessarily to support a therapeutic recommendation. Finally, any suspicion of COVID-19 infection should follow the protocols recommended by the health authorities of each country/region.

Keywords: COVID-19, Evidence map, Systematic review, Complementary therapies, Integrative medicine

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) has been encouraging and strengthening the insertion, recognition and use of traditional, complementary and integrative medicine (TCIM), products and their practitioners in national health systems at all levels of activity: primary care, specialized care and hospital care, through the recommendations of the WHO Strategy on Traditional Medicine 2014–2023 based on the regulation of quality, safety and efficacy.1

According to WHO, 43% of Latin American countries have legislation on TCIM, and 54% of them have a regulatory system for herbal therapies. Although 88% of WHO member states have recognized their use of T&CM, which corresponds to 170 member states, data from Latin America show a lack of mechanisms to monitor the safety of T&CM practices and safety of T&CM products (61%); lack of financial support for T&CM research (61%).2

Evidence maps are a useful method with the dual function of synthesizing available evidence on a specific topic and identifying knowledge gaps. It requires a systematic review of the literature and an assessment of the type and quality of available evidence. Evidence maps, unlike other synthesis methods, use graphical representations (or dynamic representations, through interactive online databases), which facilitate the interpretation of results.3

Because of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, The Brazilian Academic Consortium for Integrative Health - CABSIn, the TCIM Americas Network, and the Latin-American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information (BIREME/PAHO/WHO) have joined efforts to recruit volunteer researchers from Latin America, to systematize the available scientific evidence. The objective of this evidence map is to describe possible contributions of Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicines (TCIM) in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method

This evidence map summarizes TCIM interventions and health outcomes related to improved immunity/antiviral effect for respiratory viruses, treatment of symptoms of respiratory infections and contributions to mental health. We report the method and results according to PRISMA guidelines4 and the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3iE) Evidence Gap Methodology.5 This evidence map was supported by a technical expert panel of librarians, practitioners, policy maker and researcher content experts.

Data sources

We searched PUBMED and Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine Virtual Health Library (TCIM VHL) from database inception to March 2020 for studies published in English, Spanish and Portuguese. VHL is a decentralized and dynamic collection of information sources, designed to provide equitable access to scientific knowledge on health. It is maintained by BIREME, a PAHO Specialized Center. This collection includes databases such as LILACS, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library and SciELO. We consulted topic experts and developed the search strategy together with BIREME. A search strategy was developed, using the MeSH and DeCS terms for respiratory viral diseases associated with epidemics, COVID-19 symptoms, relevant mental health topics, pharmacological interventions related to TCIM (medicinal plants/ phytotherapy, herbal medicine, Chinese and Ayurvedic herbology, drugs related to homeopathy and anthroposophic medicine, probiotics, nutritional supplements, among others), as well as non-pharmacological TCIM interventions (yoga, taichi, mindfulness, meditation, qigong, tapping, body practices, among others). The terms used in the search strategy were reviewed by TCIM experts and researchers, and by librarians.

Inclusion criteria

-

●

Any type of Traditional and Complementary therapies interventions, of any duration and follow up;

-

●

Controlled clinical studies;

-

●

Systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses with humans, for any age group.

-

●

Relevant non-systematic reviews;

-

●

Outcomes related to improved immunity/antiviral effect for respiratory viruses, treatment of symptoms of respiratory infections or contributions to mental health (depression, social isolation, anxiety and stress disorders including work stress);

-

●

Studies in Portuguese, Spanish, and English;

-

●

All participants of all ages regardless of health status.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies that did not focus on TCIM interventions and studies not accessed in full.

Procedure

Two independent literature reviewers screened the systematic review search output blinded at the software Rayyan. Citations deemed potentially relevant by at least one reviewer and unclear citations were obtained as full text. The full-text publications were screened against the specified inclusion criteria by two independent reviewers; disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data synthesis

From each included study, we extracted the intervention (e.g., mind-body therapies practice, yoga, acupuncture) and the main health outcomes (e.g., stress, anxiety, depression) that were summarized across included studies. Researchers and health professionals duly trained in the use of Complementary Therapies in the management of symptoms, especially in the dimension of mental health and mild symptoms analyzed the data.

We developed a characterization matrix to synthesize the findings. This matrix included: Full Text Citation; Interventions; Outcomes Group; Outcomes; Effect; Population; Database ID; Focus Country; Publication Country; Publication Year; Study Design. The search and analysis of documents was performed in April 2020.

Results

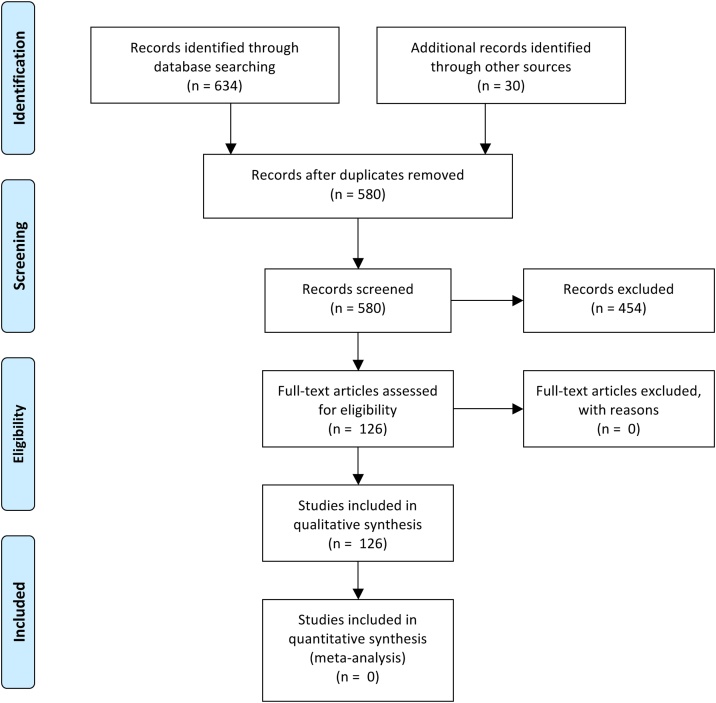

We identified 126 studies that met the criteria for inclusion in the evidence map (Fig. 1). The studies selected came from 12 countries. The complete list of references and the interactive evidence map can be accessed in the MTCI VHL, available at: http://mtci.bvsalud.org/en/contributions-of-traditional-complementary-and-integrative-medicine-tcim-in-the-context-of-covid-19/.

Fig. 1.

Literature flow.

Study design

Studies included were designed as randomized controlled studies (n = 59), non-randomized controlled studies (n = 6), Coorte (n = 1), prospective (n = 5), retrospective (n = 1), observational (n = 2), meta-analysis (n = 8), evidence maps (n = 3), systematic reviews (n = 16), systematic reviews with metaanalysis (n = 12), narrative reviews (n = 9), and scoping reviews (n = 2).

Interventions

The included studies presented 62 TCIM interventions divided into five major groups: phytotherapy (18), mind-body therapies therapies (9), traditional Chinese medicine interventions (11), Homeopathic and Anthroposophic dynamized medicines (7) and Supplements (17), as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Interventions in traditional, complementary and integrative medicines.

| Interventions Group | Interventions |

|---|---|

| Body-Mind Therapies | Mantra |

| Meditation | |

| Mindfulness | |

| Qi Gong | |

| Tai Chi | |

| Tai Chi Qi Gong | |

| Therapeutic Touch | |

| Trascendental Meditation | |

| Yoga | |

| Homeopathic and Anthroposofic dynamized medicines | Bryonia |

| Cinnabar comp (Apis venenum, Atropa belladonna, Cinnabaris) | |

| Cinnabar/Pyrite | |

| Influenza nosodes | |

| Oscillococcinum (Anas barbariae hepatis et cordis extractum) | |

| Plantago Bronchial Balm (D-Campher, Cera flava, Drosera, Eucalypti aetheroleum, Petasites hybridus, Plantago lanceolata, Terebinthina laricina, Thymi aetheroleum) | |

| Streptococcus and Staphylococcus nosodes | |

| Phytotherapy | Allium sativum |

| Brassica oleraceae | |

| Bupleurum chinense | |

| Cistus × incanus | |

| Citrus limonum | |

| Citrus × sinensis | |

| Echinacea purpurea | |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra | |

| Houttuynia cordata | |

| Lavandula angustifolia | |

| Lycium barbarum | |

| Panax ginseng | |

| Panax quinquefolius | |

| Rheum palmatum | |

| Sambucus nigra | |

| Scutellaria baicalensis | |

| Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry polyphenols) | |

| Viscum album | |

| Supplements | Catechine |

| Complex B | |

| ELOM-080 (Eucalyptus oil, Sweet orange oil, Myrtle oil, and lemon oil) | |

| Iron | |

| Lactobacillus | |

| Lactoferrin | |

| Mekabu fucoidan (algae Nemacystis decipiens) | |

| Omega-3 | |

| Pinimenthol | |

| Prebiotics | |

| Probiotics | |

| Selenium | |

| Vitamin A | |

| Vitamin C | |

| Vitamin D | |

| Vitamin E | |

| Zinco | |

| Traditional Chinese Medicine | Acupressure |

| Acupuncture | |

| Antiwei (Rhizoma Imperatae, Radix puerariae, Rhizoma Zingiberis, Ephedra sinica, Cinnamomum cassia, Prunus armeniaca, Glycyrrhiza uralensis) | |

| Auriculotherapy | |

| Chinese Herbology Medications | |

| Cupping Therapy | |

| Eletroacupunture | |

| Lianhuaqingwen | |

| Maoto (Ephedra sinica, Cinnamomum cassia, Prunus armeniaca, Glycyrrhiza uralensis) | |

| Maxingshigan–Yinqiaosan | |

| Qingwen Decoction |

Outcomes and effects

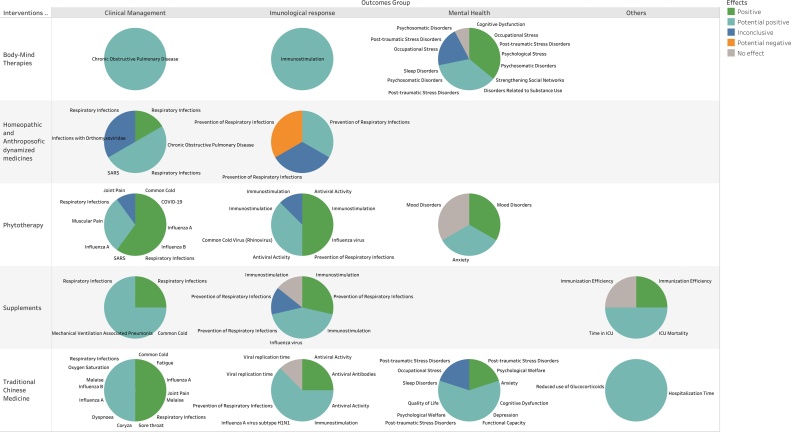

TCIM was evaluated as an intervention for several health outcomes. The 126 studies showed 67 outcomes in total divided into major groups: immunological response (14); mental health (23); complementary clinical management of the infection (25) and Others (5). Every outcome effect was classified, more than one outcome for some studies: 1 as potential negative6; 6 as no effect; 14 as inconclusive; 78 as potential positive and 47 as positive (Fig. 2). Effects classification was extracted from mapped studies’ results as reported by their authors.

Fig. 2.

Traditional, complementary and integrative medicine evidence map for interventions, outcomes and effects.

Immunological response

The results in this category have shown for mind-body therapies and traditional chinese medicine interventions potential positive effects and positive effects. For phytotherapy and Supplements there were more studies indicating potential positive and positive effects than studies indicating no effect or inconclusive effect, and for dinamized medicines the findings showed inconclusive, potential positive results and in only one study did it show one potential negative effect, headache.6

Also, in this category, a systematic review points out the relevance of the use of probiotics7 for the prevention of respiratory diseases in hospitalized patients, as well as for the improvement of the immunological8 condition as a preventive resource for cases of aggravation of the disease. Another systematic review demonstrates that the use of prebiotics and probiotics can improve the efficiency of vaccines against influenza family viruses9 a factor of great relevance for future research.

In the phytotherapy category, other clinical studies on immunostimulating activity of Echinacea purpúrea10 Viscum album,11 individualized chinese herbal therapy12 and Wolfberry13 stand out. The Viscum album has been employed mainly by the complex medical system of anthroposophic medicine.

In general, research on vitamin supplementation using Vitamin C, Vitamin D, Selenium, and other nutrients for immunological efficiency stands out as relevant only in cases of nutritional deficiency.14, 15, 16.

Mental health

This category included outcomes only related to mind-body therapies, phytotherapy and traditional Chinese medicine. There was a mix of potential positive, positive, inconclusive and no effect outcomes.

Findings in this category point to resources for post-traumatic stress disorder, relevant in a situation of pandemic and social isolation, in this category mind-body therapies and yoga,17, 18., 19., 20. meditation techniques21., 22., 23. and acupuncture24 stand out.

Other resources that promote resilience are highlighted from mindfulness25 meditation techniques with the reduction of negative affective symptoms,26 as well as factors such as stress,27, 28. anxiety and depression.28., 29., 30., 31., 32 Aromatherapy resources are also described for application in cases of anxiety.33., 34.

Management of respiratory infections symptoms

The results of the group were mostly potentially positive and positive effects with only two inconclusive outcomes. The results also call attention to evidence of various formulations for respiratory symptoms present in COVID-19, these being potential resources for management of symptoms such as fever, body pain, runny nose and other symptoms.35, 36.

The interventions with the greatest number of publications showing a positive effect refer to Chinese herbology, with systematic reviews bringing relevant conclusions for the treatment of symptoms in acute respiratory syndromes.37, 38., 39., 40. Additionally, we found studies with good positive results from prospective controlled clinical studies with the herbal medicines Sambucus nigra41 and Allium Sativum16 besides anthroposophic remedies.35, 42.

Discussion

America is now the epicenter of the pandemic worldwide.43 Despite the need for evidence-based treatment for COVID-19, another health problems are related to the pandemic, such as mental health problems and management of respiratory infections symptoms.

This TCIM evidence map is based on 126 studies and provides a broad overview of available evidence of complementary therapies in times of COVID-19. It shows the volume of available research and highlights areas where the interventions showed potential positive and positive effects.

While evidence maps can only provide a broad overview of the research, the findings have had more positive than negative effects to help guide evidence-based decisions. The reviews and controlled clinical studies selected in this map with potentially positive effects and positive effects for the outcomes studied account for 85% of publications.

The duration and frequency of the TCIM interventions cited in the studies have not been analyzed and need more research. Furthermore, inconclusive evidence warrants further research and can help to guide different institutions funding calls.

The creation and publication of evidence maps consists of graphically representing the best evidence found, analyzed and categorized, in addition to linking with the bibliographic records and full texts (when available) of the studies in order to facilitate access to information for all those interested.

Although evidence maps have several limitations, such as the fact that we only used published studies to provide an overview of the research and that no further evidence was included, for example qualitative studies. We did not calculate effect sizes in a meta-analysis, neither provide risk of bias assessments, but we tried to overcome these limitations by relying on the author’s skills in conducting and evaluation the studies quality, choice of outcomes, analysis of effects and susceptibility to publication and outcome reporting bias.

This evidence map will also not be able to answer more refined questions, such as the most adequate TCIM application, difference between health services, adequate training for practitioners, access of patients and self-application effects. Future research, including qualitative research and case studies, are necessary to answer these questions, extremely important to the development of TCIM related evidence. Future studies should also adopt economic (cost-benefit) and organizational impact assessments of health services. Gaps remain in the methodologies used by the reviews and the clinical studies included.

Although all research has been peer-reviewed and is associated with large research databases, further steps in studying this evidence should include an individual quality assessment of each clinical trial and map review. With the high speed of the number of publications on the theme of COVID-19, specific publications demonstrating the beneficial effect of TCIM in facing the pandemic should emerge generating the need for an update of this map of evidence. Despite the outlined limitations, this evidence map provides an easy visualization of TCIM valuable information for patients, health practitioners and managers, in order to promote evidence-based complementary therapies as promoted by the WHO 2014–2024 agenda.

We recommend that any suspicion of COVID-19 infection should follow the protocols recommended by the health authorities of each country/region.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to TCIM Americas Network volunteers and BIREME/PAHO/WHO for support for this research and the technical expert panel advising of the project. Any errors of fact or interpretation in this manuscript remain the responsibility of the authors. We would like do a special knowledge to Natalia Sofia Aldana, Alan Kornin, Lissandra Zanovelo Fogaça, Alan da Silva Menezes de Assis, Daniel Alan Costa, Mikaelly Pereira Coser, Fabian, Laszlo Flegner, Erika Cardozo Pereira, Danilo Alberti dos Santos, Gleyce Moreno Barbosa, Priscilla Araújo Duprat de Britto Pereira, Rosely Cordon, Cassio Guedes Pelegrini Junior, Raquel da Silva Terezam, Leila Brito Bergold, Raquel de Luna Antonio, Andres Felipe Rodriguez Molina.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: CF, RG, CV, MC; Methodology: CV, MC; Formal Analysis: CF, CV; Investigation: CF, RG, CV, MC; Data Curation: CF, CV; Writing – Original Draft: MC, CF; Writing – Review & Editing: CF, RG, CV, MC; Supervision: RG, CV; Project Administration: CV.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical statement

This research did not require an ethical approval as it does not involve any human or animal experiment.

Data availability

Study flow was tracked in citation management software and data were extracted in online systematic review programs – Mendeley, Rayyan and Excel; all files can be obtained from the authors. The complete list of included studies is in the public domain, available at the Virtual Health Library (VHL) - http://mtci.bvsalud.org/en/evidence-map/.

Footnotes

Search strategy can be found in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imr.2020.100473.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Organization WH. WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine 2019. WHO Glob. Rep. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2019, WHO; 2019.

- 2.Organización Mundial de la Salud . Organ Mund La Salud; 2013. Estrategia de la OMS sobre medicina tradicional 2014-2023; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant M.J., Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26:91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snilstveit B., Vojtkova M., Bhavsar A., Stevenson J., Gaarder M. Evidence & Gap Maps: a tool for promoting evidence informed policy and strategic research agendas. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;79:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathie R.T., Frye J., Fisher P. Homeopathic Oscillococcinum® for preventing and treating influenza and influenza-like illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2017 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001957.pub6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrof E.O., Dhaliwal R., Manzanares W., Johnstone J., Cook D., Heyland D.K. Probiotics in the critically ill: a systematic review of the randomized trial evidence. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:3290–3302. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318260cc33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akatsu H., Iwabuchi N., Xiao J.Z., Matsuyama Z., Kurihara R., Okuda K. Clinical effects of probiotic bifidobacterium longum BB536 on immune function and intestinal microbiota in elderly patients receiving enteral tube feeding. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2013;37:631–640. doi: 10.1177/0148607112467819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Te Lei W., Shih P.C., Liu S.J., Lin C.Y., Yeh T.L. Effect of probiotics and prebiotics on immune response to influenza vaccination in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2017;9:1175. doi: 10.3390/nu9111175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sperber S.J., Shah L.P., Gilbert R.D., Ritchey T.W., Monto A.S. Echinacea purpurea for prevention of experimental rhinovirus colds. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1367–1371. doi: 10.1086/386324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chernyshov V.P., Heusser P., Omelchenko L.I., Chernyshova L.I., Vodyanik M.A., Vykhovanets E.V. Immunomodulatory and clinical effects of Viscum album (Iscador M and Iscador P) in children with recurrent respiratory infections as a result of the chernobyl nuclear accident. Am J Ther. 2000;7:195–203. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200007030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poon P.M.K., Wong C.K., Fung K.P., Fong C.Y.S., Wong E.L.Y., Lau J.T.F. Immunomodulatory effects of a traditional Chinese medicine with potential antiviral activity: a self-control study. Am J Chin Med. 2006;34:13–21. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X0600359X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vidal K., Bucheli P., Gao Q., Moulin J., Shen L.S., Wang J. Immunomodulatory effects of dietary supplementation with a milk-based wolfberry formulation in healthy elderly: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Rejuvenation Res. 2012;15:89–97. doi: 10.1089/rej.2011.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L., Liu Y. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: a systemic review. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee M.D., Lin C.H., Te Lei W., Chang H.Y., Lee H.C., Yeung C.Y. Does vitamin D deficiency affect the immunogenic responses to influenza vaccination? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2018;10:409. doi: 10.3390/nu10040409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mousa H.A.L. Prevention and treatment of influenza, influenza-like illness, and common cold by herbal, complementary, and natural therapies. J Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med. 2017;22:166–174. doi: 10.1177/2156587216641831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan-Porter W., Coeytaux R.R., McDuffie J.R., Goode A.P., Sharma P., Mennella H. Evidence map of yoga for depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Phys Act Heal. 2016;13:281–288. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2015-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilton L., Maher A.R., Colaiaco B., Apaydin E., Sorbero M.E., Booth M. Meditation for posttraumatic stress: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Trauma Theory, Res Pract Policy. 2017;9:453–460. doi: 10.1037/tra0000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Love M.F., Sharrief A., Chaoul A., Savitz S., Beauchamp J.E.S. Mind-body interventions, psychological stressors, and quality of life in stroke survivors: A systematic review. Stroke. 2019;50:434–440. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cushing R.E., Braun K.L. Mind-body therapy for military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24:106–114. doi: 10.1089/acm.2017.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilton L., Maher A.R., Colaiaco B., Apaydin E., Sorbero M.E., Shanman R.M. Psychological trauma: Theory, research, practice, and policy meditation for posttraumatic stress: systematic review meditation for posttraumatic stress: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Trauma Theory, Res Pract Meta-Analysis. 2017;9:453–460. doi: 10.1037/tra0000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heffner K.L., Crean H.F., Kemp J.E. Meditation programs for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: aggregate findings from a multi-site evaluation. Psychol Trauma Theory, Res Pract Policy. 2016;8:365–374. doi: 10.1037/tra0000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallegos A.M., Crean H.F., Pigeon W.R., Heffner K.L. Meditation and yoga for posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;58:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant S., Colaiaco B., Motala A., Shanman R., Sorbero M., Hempel S. Acupuncture for the treatment of adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Dissociation. 2018;19:39–58. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1289493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joyce S., Shand F., Tighe J., Laurent S.J., Bryant R.A., Harvey S.B. Road to resilience: a systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. BMJ Open. 2018;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carpenter J.K., Conroy K., Gomez A.F., Curren L.C., Hofmann S.G. The relationship between trait mindfulness and affective symptoms: a meta-analysis of the five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;74 doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strauss C., Thomas N., Hayward M. Can we respond mindfully to distressing voices? A systematic review of evidence for engagement, acceptability, effectiveness and mechanisms of change for mindfulness-based interventions for people distressed by hearing voices. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pascoe M.C., Thompson D.R., Jenkins Z.M., Ski C.F. Mindfulness mediates the physiological markers of stress: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;95:156–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dusek J.A., Abrams D.I., Roberts R., Griffin K.H., Trebesch D., Dolor R.J. Patients receiving integrative medicine effectiveness registry (PRIMIER) of the BraveNet practice-based research network: Study protocol. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1025-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang J., Nigatu Y.T., Smail-Crevier R., Zhang X., Wang J. Interventions for common mental health problems among university and college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;107:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patwardhan B., Warude D., Pushpangadan P., Bhatt N. Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine: a comparative overview. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:465–473. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams Jr J.W., Gierisch J.M., McDuffie J., Strauss J.L., Nagi A., Wing L. Suppl to Effic Complement Altern Med Ther Posttraumatic Stress Disord [Internet] Washingt Dep Veterans Aff; 2011. An overview of complementary and alternative medicine therapies for anxiety and depressive disorders. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mannucci C., Calapai F., Cardia L., Inferrera G., D’Arena G., Di Pietro M. Clinical pharmacology of citrus aurantium and citrus sinensis for the treatment of anxiety. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/3624094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karan N.B. Influence of lavender oil inhalation on vital signs and anxiety: a randomized clinical trial. Physiol Behav. 2019;211 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.112676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamre H.J., Fischer M., Heger M., Riley D., Haidvogl M., Baars E. Anthroposophic therapy of respiratory and ear infections. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117:500–501. doi: 10.1007/s00508-005-0389-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao P., Yang H.Z., Lv H.Y., Wei Z.M. Efficacy of lianhuaqingwen capsule compared with oseltamivir for influenza a virus infection: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Altern Ther Health Med. 2014;20:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu X., Zhang M., He L., Li Y. Chinese herbs combined with Western medicine for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004882.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen W., Lim C.E.D., Kang H.J., Liu J. Chinese herbal medicines for the treatment of type A H1N1 influenza: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J., Manheimer E., Shi Y., Gluud C. Chinese herbal medicine for severe acute respiratory syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10:1041–1051. doi: 10.1089/acm.2004.10.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang M.M., Liu X.M., He L. Effect of integrated traditional Chinese and Western medicine on SARS: a review of clinical evidence. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3500–3505. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i23.3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zakay-Rones Z., Thom E., Wollan T., Wadstein J. Randomized study of the efficacy and safety of oral elderberry extract in the treatment of influenza A and B virus infections. J Int Med Res. 2004;32:132–140. doi: 10.1177/147323000403200205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamre H.J., Glockmann A., Schwarz R., Riley D.S., Baars E.W., Kiene H. Antibiotic use in children with acute respiratory or ear infections: prospective observational comparison of anthroposophic and conventional treatment under routine primary care conditions. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/243801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Organization WH . Situation; 2020. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak situation. Coronavirus dis outbreak situat.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200503-covid-19-sitrep-104.pdf?sfvrsn=53328f46_2 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Study flow was tracked in citation management software and data were extracted in online systematic review programs – Mendeley, Rayyan and Excel; all files can be obtained from the authors. The complete list of included studies is in the public domain, available at the Virtual Health Library (VHL) - http://mtci.bvsalud.org/en/evidence-map/.