SUMMARY

Mitochondrial dysfunction and proteostasis failure frequently coexist as hallmarks of neurodegenerative disease. How these pathologies are related is not well understood. Here, we describe a phenomenon termed MISTERMINATE (mitochondrial-stress-induced translational termination impairment and protein carboxyl terminal extension), which mechanistically links mitochondrial dysfunction with proteostasis failure. We show that mitochondrial dysfunction impairs translational termination of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs, including complex-I 30kD subunit (C-I30) mRNA, occurring on the mitochondrial surface in Drosophila and mammalian cells. Ribosomes stalled at the normal stop codon continue to add to the C terminus of C-I30 certain amino acids non-coded by mRNA template. C-terminally extended C-I30 is toxic when assembled into C-I and forms aggregates in the cytosol. Enhancing co-translational quality control prevents C-I30 C-terminal extension and rescues mitochondrial and neuromuscular degeneration in a Parkinson’s disease model. These findings emphasize the importance of efficient translation termination and reveal unexpected link between mitochondrial health and proteome homeostasis mediated by MISTERMINATE.

In Brief

Non-templated C-terminal alanine (Ala) and threonine (Thr) addition to nascent peptides occurs during translational stalling. So far, this CAT-tailing phenomenon has only been shown with reporter constructs. Wu et al. describe a CAT-tailing-like MISTERMINATE process happening to respiratory chain proteins in Parkinson’s disease models and patient cells, linking CAT-tailing to neurodegenerative disease.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Protein aggregation is a defining feature of age-related diseases. Hallmark aggregates include those composed of Aβ, α-Syn, tau, and TDP-43 in various neurodegenerative diseases (Hartl, 2017; Chiti and Dobson, 2017). While it remains unclear whether the large aggregates or some smaller intermediates are the toxic species (Hartl, 2017; Sontag et al., 2017), accumulation of faulty proteins seems to be at play. Previous studies have focused on alterations of mature proteins. Such changes emphasize post-translational modifications, and significant efforts have been directed toward linking these molecular events with agingrelated effects, such as oxidative stress and impairments of the autophagy and ubiquitin-proteosome system (UPS) (Bossy-Wetzel et al., 2004; Ciechanover and Brundin, 2003). Recent studies draw attention to an emerging role of co-translational quality control (QC) of nascent peptide chains (NPCs) in proteome homeostasis (Brandman and Hegde, 2016; Joazeiro, 2017). Ubiquitination and degradation of NPCs associated with stalled as well as active translation is widespread (Wang et al., 2013a; Duttler et al., 2013). NPCs on stalled ribosomes can be modified, while still attached to 60S, by C-terminal alanine (Ala) and threonine (Thr) addition (CAT-tailing) (Shen et al., 2015). This may enable the degradation of aberrant NPCs by making most recently added K residues available for ubiquitination (Kostova et al., 2017). While CAT-tailing as part of the ribosome-associated quality control (RQC) complex may induce the heat shock response (Brandman et al., 2012) or drive degradation of stalled NPCs on and off the ribosomes (Sitron and Brandman, 2019), failure in the timely removal of CAT-tailed proteins can disrupt proteostasis and cause cytotoxicity (Choe et al., 2016; Yonashiro et al., 2016; Defenouillère et al., 2016). Whether this relates to the neurodegeneration caused by mutations in certain RQC genes in mammals (Chu et al., 2009; Ishimura et al., 2014) remains to be seen, as no endogenous CAT-tailing substrate has been found in any organism.

Mitochondrial dysfunction is another pathological hallmark of neurodegenerative disease (Johri and Beal, 2012). In addition to producing ATP, mitochondria host a vast array of metabolic pathways and control Ca2+ homeostasis, apoptosis, etc. Mitochondrial dysfunction is profoundly implicated in major human diseases, from neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases to stroke, diabetes, and cancer (Sorrentino et al., 2018). Disease-associated proteins frequently interact with or enter into mitochondria and interfere with essential functions, and environmental toxins can cause disease by targeting mitochondria (Coskun et al., 2012). How mitochondrial dysfunction arises and contributes to the often tissue- and cell-type-specific pathologies remains enigmatic. Energy supplement has been largely ineffective in treating diseases associated with mitochondrial dysfunction (Weber and Ernst, 2006), implying other pathogenic mechanisms.

The co-presence of proteostasis failure and mitochondrial dysfunction as pathological hallmarks suggests a mechanistic link. In the Drosophila PINK1 model of Parkinson’s disease (PD) with primary mitochondrial defect, reduction of global protein synthesis to relieve demand for protein QC was beneficial (Liu and Lu, 2010). In a mouse model of Leigh syndrome caused by a mitochondrial complex-I defect, inhibition of mRNA translation via mTORC1 slowed disease progression (Johnson et al., 2013). These studies imply an intimate connection between mitochondria and cytosolic translation, albeit with an unclear mechanism.

Here, we show that mitochondrial damage induces translational stalling of mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM)-associated complex-I 30kD subunit (C-I30) mRNA by impairing the termination and ribosome-recycling factors eRF1 and ABCE1. Stalled ribosomes continue to add certain aa to the C terminus of C-I30 in a process analogous to CAT-tailing but with distinct features. C-I30 with C-terminal extension (CTE) inhibits oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) when assembled into complex-I (C-I) and disrupts proteostasis when aggregating in the cytosol. Genetic manipulations of eRF1, ABCE1, or conserved CAT-tailing machinery prevent C-I30 CTE and rescue neuromuscular degeneration in a PINK1 PD model. We also show that PINK1/Parkin regulates the CTE process. These results identify an endogenous CAT-tailing substrate, with implications for understanding the link between mitochondrial dysfunction and proteostasis failure in diseases.

RESULTS

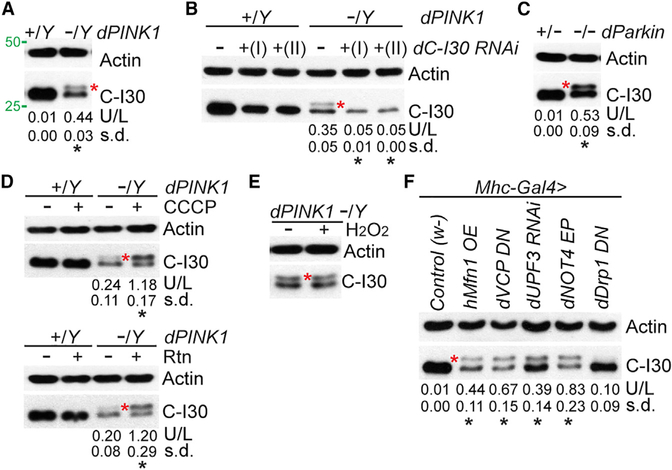

Detection of C-I30-u in PINK1 Neuromuscular Tissues

C-I30 is part of the core assembly of human C-I, the largest of the respiratory chain complexes (Formosa et al., 2018). C-I30 mRNA is recruited to MOM and translationally regulated by PINK1 and Parkin (Gehrke et al., 2015), two factors linked to familial PD. In muscle and brain tissues of PINK1 flies, we detected canonical C-I30, which ran at ~26 kDa on SDS-PAGE gel, reflecting removal of the mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) from the preprotein. This was the only C-I30 band detected in wild-type (WT) flies. A slower migrating band (C-I30-u), however, was detected in PINK1 flies (Figure 1A). C-I30-u was detectable on high percentage (12%−15%) SDS-PAGE gels running in the Tris-glycine-SDS, but not the MOPS buffer system (data not shown). Both C-I30 and C-I30-u were reduced in PINK1 flies expressing independent C-I30 RNAi transgenes (Figure 1B), demonstrating antibody specificity. C-I30-u was also observed in parkin flies (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. C-I30-u Formation in Mutant Flies Suffering Mitochondrial Insults.

(A) Immunoblots of thoracic muscle extracts from WT (dPINK1+/Y) and PINK1 (dPINK1-/Y) flies. Asterisk indicates C-I30-u. Values under the blots represent mean and SD of the ratio of C-I30 upper band/lower band (U/L), accompanied by statistical tests, in this and all subsequent figures. Actin serves as a loading control.

(B) Immunoblots of muscle samples from WT and PINK1 flies with C-I30 knocked down by two different transgenes.

(C) Immunoblots of muscle samples from dParkin1/+ and dParkin1/Δ21 flies.

(D) Immunoblots of muscle samples from WT and PINK1 flies with or without CCCP or rotenone (Rtn) treatment.

(E) Immunoblots of muscle samples from PINK1 flies with or without H2O2 treatment.

(F) Immunoblots of muscle samples from various transgenic flies. w-, WT control.

See also Figure S1.

C-I30-u Induction by Mitochondrial Stress

To probe how C-I30-u was formed, we pharmacologically treated PINK1 flies. The C-I inhibitor rotenone, or the protonophore and mitochondrial uncoupler carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP), caused a significant increase of C-I30-u relative to C-I30 (Figure 1D), but H2O2 had no obvious effect (Figure 1E). Knocking down subunit C of complex V (C-V) also increased the C-I30-u/C-I30 ratio, but surprisingly, subunit α (bellweather [blw]) knockdown showed the opposite effect (Figure S1A). Previous studies showed that overexpression (OE) of the mitochondrial fusion GTPase hMfn1 (Ziviani et al., 2010), or a dominant-negative form of the AAA+ ATPase VCP (Kim et al., 2013), caused mitochondrial dysfunction and muscle degeneration (Figures S1B and S1C), phenocopying PINK1 or parkin. These conditions also induced C-I30-u (Figure 1F). Although inhibiting Drp1 has similar effect as hMfn1-OE on mitochondrial morphology (Ziviani et al., 2010), it did not obviously affect C-I30-u (Figure 1F), suggesting that the effect of hMfn1 on C-I30-u is independent of fission or fusion.

Translational Control of C-I30-u Formation

We explored the molecular basis of C-I30-u formation. One possibility is alternatively splicing. Arguing against this possibility, RT-PCR analysis failed to identify such mRNAs, and C-I30-u was still formed when a fully spliced C-I30 cDNA was expressed as a transgene (C-I30–3xHA) in PINK1, but not WT, flies (Figure S2A). Moreover, when a cDNA encoding FLAG-tagged C-I30 was expressed in HeLa cells, C-I30-u was induced by either CCCP or the respiratory chain inhibitors oligomycin and antimycin A (Figures 2A and S2B), although a low level of tagged C-I30-u was detectable in HeLa cells without treatment (see explanation later). Thus, different mitochondrial insults can trigger C-I30-u formation. Phosphatase or ubiquitin protease failed to alter C-I30-u (Figures 2B and 2C). Intriguingly, C-I30-u was significantly higher in HeLa cells, which express negligible level of Parkin, compared to HeLa cells stably transfected with GFP-Parkin (Figure 2D), suggesting that Parkin restricts the formation of C-I30-u.

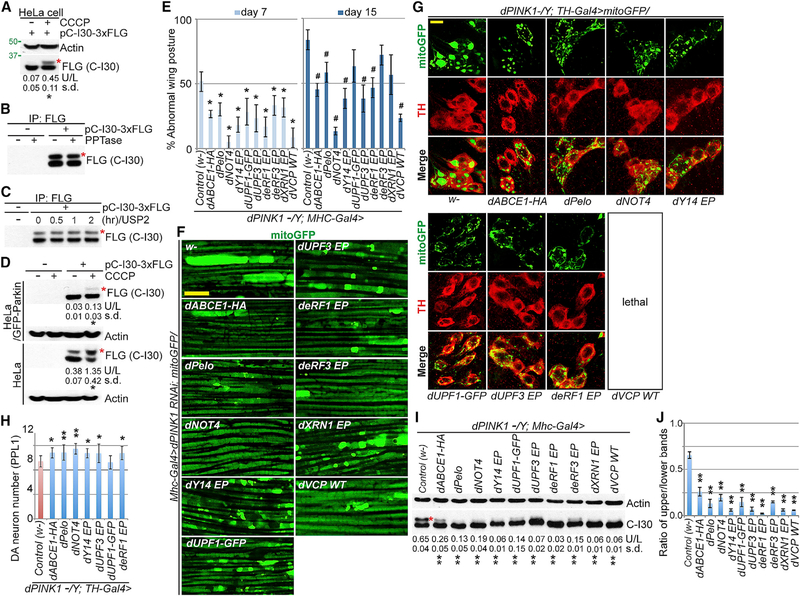

Figure 2. Co-translational QC Genes Regúlate C-I30-u Formation.

(A) Immunoblots of HeLa cells transfected with C-I30-FLAG and treated with 20 μM CCCP.

(B and C) Immunoblots of C-I30-FLAG and C-I30-FLAG-u after phosphatase (PPTase; B) or ubiquitin specific protease 2 (USP2; C) treatment.

(D) Immunoblots of lysates from HeLa or Hela (GFP-Parkin) cells transfected with C-I30-FLAG and with or without CCCP treatment.

(E) Rescue of the PINK1 wing phenotype by QC factors. *p<0.05 and **p < 0.01, Student-Newman-Keuls test (SNK-test) plus Bonferroni correction versus PINK1 group at day 7 or 15, respectively.

(F) Rescue of mitochondrial morphology by QC factors in PINK1 RNAi fly muscle.

(G and H) Rescue of PINK1 DA neuron mitochondrial morphology (G) and number (H) by QC factors. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, SNK-test plus Bonferroni correction versus control (w-).

(I) Immunoblots of muscle samples from PINK1 flies expressing UAS transgenes or enhancer P-element (EP) lines driven by Mhc-Gal4. w-, WT control.

(J) Data quantification of (I). **p < 0.01 in SNK-test plus Bonferroni correction versus control (w-).

Error bars represent SD from three independent assays and normalized with control. Scale bars, 5 μm (F-H). Mitochondrial morphology is monitored with mito-GFP in this and all subsequent figures. See also Figure S2.

Another possibility is that C-I30-u represents C-I30 preprotein. This is unlikely, since unlike other proteins synthesized as preprotein in the cytosol and later imported into mitochondria when MTS is removed, C-I30 engages in co-translational import on MOM (Gehrke et al., 2015). Thus, after the MTS exiting the ribosome and translocated by TOM-TIM, it would be cleaved. Consistently, mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of C-I30-u failed to identify the MTS (see later). To further test this possibility, we mutated the MTS cleavage site in C-I30-FLAG. This construct also produced two bands, with the upper band promoted by mitochondrial stress (Figure S2C). The upshift of this MTS mutant C-I30-FLAG compared to WT C-I30-FLAG verified blockage of MTS processing, and both forms of the protein were protected from protease treatment, indicating import into mitochondria (Figure S2D). This result ruled out C-I30-u being a preprotein.

Co-translational QC Pathways Regúlate C-I30-u Formation

We sought to gain insight into C-I30-u formation through systematic genetic analysis. Given that PINK1/Parkin regulates C-I30 translation on the MOM (Gehrke et al., 2015), we focused on genes in co-translational QC pathways, including the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), no-go decay, non-stop decay, and RQC pathways, which are mechanistically related and share certain components (Brandman and Hegde, 2016). We used the PINK1 wing posture phenotype, caused by mitochondrial and muscle degeneration (Yang et al., 2006), as a readout of genetic interaction. Remarkably, OE of co-translational QC factors, with the OE effect verified for certain key factors (Figure S2E), effectively rescued PINK1 phenotypes in the muscle (Figures 2E and 2F) and disease-relevant dopaminergic (DA) neurons (Figures 2G and 2H). Correspondingly, the C-I30-u level was reduced (Figures 2I and 2J). Loss of function of co-translational QC genes in PINK1 mutant showed little effect on C-I30-u (Figures S2F and S2G), likely because they work in the same pathway to regulate C-I30-u. However, there are exceptions, as shown later.

Consistent with the co-translational QC genes working in the same pathway as PINK1 to control C-I30-u expression and mitochondrial function, muscle-specific knockdown of UPF3, a key NMD factor (Leeds et al., 1992), was sufficient to phenocopy PINK1. Muscle-specific expression of dominant-negative VCP, a key RQC factor (Brandman et al., 2012), or OE of NOT4, a protein implicated in the co-translational QC of C-I30 (Wu et al., 2018), also phenocopied PINK1 (Figures 1F, S1B, and S1C).

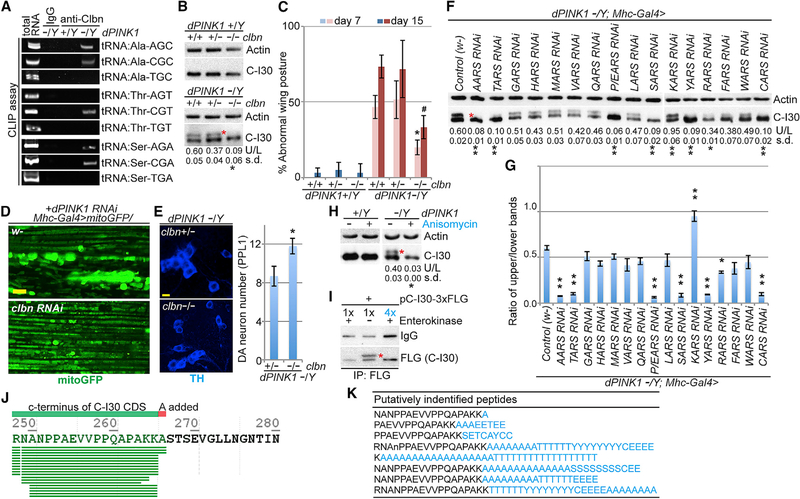

One exception to the general trend of co-translational QC gene interaction with PINK1 is Clbn (Bi et al., 2005), the fly homolog of yeast RQC2 or Tae2. RQC2 or Tae2 recruits charged Ala- and Thr-tRNAs to stalled ribosomes and is required for CAT-tailing in yeast (Shen et al., 2015). In cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP) assays, Clbn binds to Ala- and Thr-tRNAs and, to a lesser extent, Ser-tRNA (Figure 3A). clbn mutant has no obvious phenotype under normal conditions (Wang et al., 2013b). When introduced into PINK1 mutant, complete loss of clbn abolished C-I30-u formation, whereas 50% loss had no obvious effect (Figure 3B). Complete loss of clbn rescued the wing posture (Figure 3C), ATP production (Figure S3A), mitochondrial morphology (Figures 3D and S3B), and DA neuron loss (Figure 3E) phenotypes of PINK1.

Figure 3. C-I30-u Behaves as a CTE Form of C-I30.

(A) CLIP assay showing binding of specific tRNAs to Clbn in PINK1 mutant.

(B) Immunoblots of muscle samples from WT and PINK1 flies with loss of one or two copies of clbn.

(C) Effect of clbn on wing posture in the WT and PINK1 conditions. *p < 0.05 or #p < 0.05 in SNK-test plus Bonferroni correction versus PINK1 at day 7 or 15, respectively.

(D) Effect of clbn RNAi on mitochondrial morphology in PINK1 RNAi fly muscle.

(E) Rescue of DA neuron number by clbn in PINK1 flies. **p < 0.01, two-tailed Student’s t test.

(F and G) Immunoblots of muscle samples from PINK1 flies expressing AARS RNAi transgenes. (G) shows a data quantification of (F). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 in SNK-test plus Bonferroni correction versus control (w-).

(H) Immunoblots of muscle samples from WT and PINK1 flies treated with anisomycin.

(I) Immunoblots of enterokinase (EK)-treated C-I30-FLAG and C-I30-FLAG-u. The post-digestion product showed reduced FLAG reactivity due to removal of one residue from the epitope. 1× and 4× products were loaded to match the uncut sample.

(J) C-terminal peptides identified from generic database searches of fly C-I30-u peptides (see Table S1). SEVGLLNGNA, read-through sequence.

(K) Longer CTE peptides identified from customized pool-based searches. Amino acids (aa) in black, C-I30 CDS; aa in blue, CTE (see Table S2).

Scale bars, 5 mm (D and E). See also Figure S3.

The above results supported C-I30-u formation by a CAT-tailing-like process. To test this further, we examined the requirement for Ala- or Thr-tRNA synthetase (AARS or TARS). Partial inhibition of AARS or TARS preferentially reduced C-I30-u formation (Figures 3F and 3G) and mitochondrial aggregation caused by PINK1 inhibition (Figure S3C). SARS, YARS, CARS, or E/PARS had a similar effect (Figures 3F, 3G, and S3C). The specificity of the ARS effect was demonstrated by lack of effect of the rest of the ARSs tested, with the exception of KARS, whose RNAi moderately increased C-I30-u (Figures 3F and 3G). Anisomycin, which targets the peptidyl-transferase center and can inhibit CAT-tailing in vitro (Osuna et al., 2017), inhibited C-I30-u formation in fly muscle (Figures 3H and S3D). These data indicate that C-I30-u is formed through the addition of Ala (A), Thr (T), and possibly other select aa in a CAT-tailing like process.

C-I30-u Is a CTE Form of C-I30

To further characterize C-I30-u, we used C-I30 constructs containing epitope tags allowing carboxyl-terminal (C-term) analysis. Transfected HeLa cells were treated with CCCP to induce C-I30-u. In the C-I30-FLAG-AK construct, a 3xFLAG tag was inserted 2 codons (encoding AK) before the UAG stop codon. This construct showed CCCP induction of C-I30-FLAG-u (Figure 2A). Cleavage of FLAG with enterokinase removed C-I30-FLAG-u (Figure 3I), consistent with C-I30-FLAG-u having CTE. Although we designed our constructs with the initial thinking that the K at the very end might play a role in CTE, deleting that K or adding another K had no obvious effect (Figure S3E). We made two other constructs, C-I30-TEV-FLAG and C-I30-FLAG-TEV, with a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease-cleavage site inserted before or after FLAG. Both constructs showed C-I30-u induction by CCCP (Figure S3F). With C-I30-TEV-FLAG, we could trace the TEV protease-released CTE with anti-FLAG. Two FLAG-positive fragments (FLAG alone and FLAG with tail) were detected, supporting C-I30-TEV-FLAG-u being a CTE form (Figure S3G).

To determine the nature of the CTE in C-I30-u, we performed mass spectrometry (MS) of C-I30-u purified from PINK1 flies. We took advantage of the fact that C-I30-u is less soluble than C-I30. By enriching for insoluble proteins followed by denaturing immunoprecipitation (IP), we obtained relatively pure C-I30-u (Figure S3H), which was subjected to gel purification, in-gel partial digestion with trypsin, and MS of released peptides. No strong signals for peptides containing MTS, or post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as phosphorylation or ubiquitination, were found. We also did not find evidence of read-through after the stop codon. Based on in vivo aminoacyl tRNA synthetase (ARS) dependency of C-I30-u, we hypothesized that A, T, Ser (S), Tyr (Y), Cys (C), Glu (E), or Pro (P) might be the preferred aa in the CTE, and we built a custom library with that in mind. The MS data supported that notion. For example, a search of tandem mass spectra against the databases frequently identified the peptide with an A added to the very C-term fragment of C-I30 (RNANPPAEVVPPQAPAKK.A), suggesting that A is more preferred at the first position of the CTE (Figures 3J and 3K; Table S1). Since C-I30-u ran as a rather discrete band on SDS-PAGE with an estimated molecular weight (MW) ~3–4 kDa larger than C-I30, we searched for peptides with longer CTE against customized databases. Due to size limitation of the database that could be used in this analysis, we could not exhaust searching all possible aa combinations in the CTE. Nevertheless, our searches uncovered putative longer CTEs containing A, T, and the other preferred aa (Figure 3K; Table S2). Peptide spectra produced by collision-induced dissociation were identified and manually examined (Figure S3I). The shorter peptides we identified might reflect cleavage of the CTEs by trypsin or length heterogeneity of the CTEs hidden by the discrete banding pattern of C-I30-u on SDS-PAGE. Analysis of C-I30 purified from WT flies did not find such CTEs, and searches of databases composed of aa whose ARSs knockdown did not affect C-I30-u came up mostly negative (data not shown). Thus, C-I30 CTE in Drosophila is analogous to CAT-tailing in yeast but with distinct features.

A Stress-Induced Defect in Translation Termination Triggers C-I30-u Formation

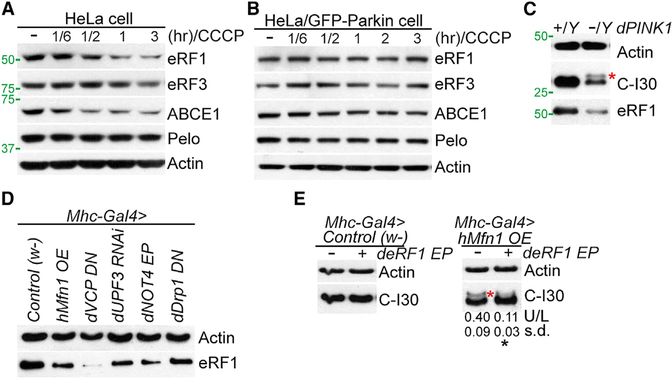

A unique feature of C-I30 CTE is that aa are added to full-length C-I30 instead of incomplete NPCs. We wondered if this is because mitochondrial stress affects normal translation termination. CCCP reduced levels of eRF1 and ABCE1, but not eRF3, in HeLa cells (Figure 4A). Correlating with inhibition of C-I30-u formation by Parkin (Figure 2D), Parkin blocked the CCCP effect on eRF1 and ABCE1 (Figure 4B). Parkin also promoted the ABCE1-eRF1 and ABCE1-Pelo interaction (Figure S4A), suggesting that it normally ensures the fidelity of translation termination and/or ribosome recycling.

Figure 4. eRF1 Regulates C-I30-u Formation.

(A and B) Immunoblots of indicated proteins in CCCP-treated HeLa cells (A) or HeLa (GFP-Parkin) cells (B).

(C) Immunoblots of eRF1 in muscle sample of WT and PINK1 flies. The same blot as in Figure 1A is used.

(D) Immunoblots of eRF1 in muscle samples from WT flies expressing various transgenes.

(E) Immunoblots showing removal of C-I30-u by eRF1-OE.

See also Figure S4.

We next tested the in vivo relevance of the cell culture studies. Full-length eRF1 was reduced in PINK1 muscle tissue (Figure 4C). Due to the lack of antibodies, we could not examine fly ABCE1 and eRF3. eRF1 was also reduced in UPF3-RNAi, VCP-DN, NOT4, or hMfn1 OE flies (Figure 4D), which phenocopied PINK1. Intriguingly, concomitant with the reduction of full-length eRF1, a smaller-sized eRF1 appeared (Figure S4B), suggesting that eRF1 might be processed under these conditions. Importantly, eRF1-OE reduced C-I30-u in PINK1 (Figure 2I) or hMfn-OE flies (Figure 4E), and rescued their mitochondrial and muscle phenotypes (Figures 2E, 2F, and S4C). Moreover, eRF1-OE rescued the mitochondrial and DA neuron degeneration in PINK1 flies (Figures 2G and 2H). ABCE1-OE had a similar effect (Figures 2E–2H and 2I). Supporting C-I30 being a critical target mediating eRF1 and ABCE1 effects, C-I30 RNAi blocked the rescue of PINK1 by eRF1-, ABCE1-, or UPF3-OE, although C-I30 RNAi alone did not cause toxicity or modify PINK1 phenotypes (Figures S4D and S4E).

These results establish impaired translation termination due to eRF1-ABCE1 alteration as a cause of mitochondrial-stress-induced translational stalling and ensuing RQC. We term this phenomenon mitochondrial-stress-induced translational termination impairment and protein CTE (MISTERMINATE).

C-I30-u Assembly into Respiratory Chain Inhibits Energetics and Cellular Survival

The strict correlation between C-I30-u abundance and disease severity in vivo suggests that it may interfere with mitochondrial function and neuromuscular integrity. Within C-I, the C terminus of C-I30 was found in the vicinity of NDUFS1, S4, A5, and A7, but the last 14 aa (SLKLEAGDKKPDAK) were not included due to poor electron density (Gu et al., 2016), suggesting that it may exist in a dynamic state and be regulatory. If so, assembly of C-I30-u into C-I may alter C-I function.

We examined the assembly of C-I30 into C-I. First, we found that in contrast to mito-dsRed, which was synthesized in the cytosol and later imported into mitochondria and thus present in both fractions, C-I30 was found exclusively in the mitochondria fraction (Figure S4F). Moreover, a C-I30 construct containing amino-terminal (N-term) HA and C-term FLAG revealed mitochondria-associated C-I30 intermediate species positive for hemagglutinin (HA), but not FLAG, which are likely partially synthesized C-I30 (Figure S4G). These data further supported the co-translational import of C-I30.

Using two-dimensional (2D) gel, with blue native gel (BNG) being the first dimension to separate large mitochondrial complexes and SDS-PAGE the second dimension to separate constituents of the complexes, we found both C-I30 and C-I30-u in C-I of PINK1 muscle tissues (Figure 5A). The complexes containing C-I30 and C-I30-u were verified as C-I and C-I-associated super-complex based on co-migration of C-I marker (Figure 5A). Thus C-I30-u is assembled into complex-I in vivo, potentially causing mitochondrial toxicity. C-I30-u was also found assembled into C-I in HeLa cells (Figure S5A). Although CCCP was used to induce C-I30-u in HeLa cells and high CCCP concentrations could depolarize mitochondria and arrest C-I30 and C-I30-u import, under our conditions, co-translational import was likely slowed down, but not completely stalled. Slow-down of co-translational import can cause ribosome collision, a triggering event of RQC (Juszkiewicz et al., 2018). Thus, MISTERMINATE and import of C-I30 and C-I30-u both occurred.

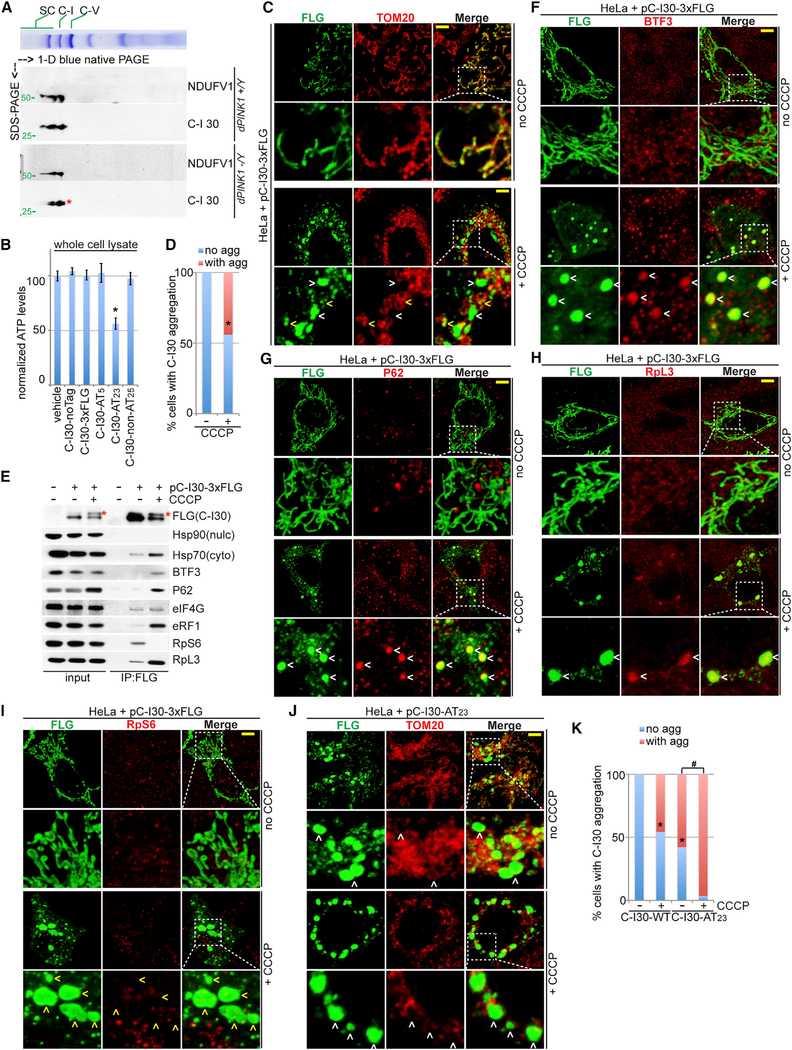

Figure 5. C-I30-u Is Assembled into C-I and Can Form Cytosolic Aggregates.

(A) Immunoblots of 2D gel showing assembly of C-I30-u into the RCC of mitochondria purified from PINK1 flies. Another C-I marker, NDUFV1, serves as a positive control.

(B) ATP measurement in HeLa cells expressing non-tagged C-I30 and C-I30-CAT-Tail. *p < 0.05, SNK-test plus Bonferroni correction versus control (w-).

(C) Immunostaining showing C-I30 aggregation in CCCP-treated HeLa cells. Scale bar, 3 μm. Arrowheads indicate aggregates outside (white) or inside (yellow) mitochondria.

(D) Qualification of data shown in (C). *p < 0.05, chi-squared test.

(E) FLAG IP from HeLa cells transfected with C-I30-FLAG, with or without CCCP treatment.

(F-I) Immunostaining of HeLa cells transfected with C-I30-FLAG and treated with or without CCCP. Scale bar, 3 μm. White arrowheads indicate aggregates colocalizing with BTF3 (F), P62 (G), or RpL3 (H), and yellow arrowheads indicate no RpS6 colocalization (I).

(J) Immunostaining of HeLa cells transfected with C-I30-FLAG-AT23, with or without CCCP. Arrowheads indicate extra-mitochondrial aggregates.

(K) Qualification of data shown in (J). *p < 0.05 and #p < 0.05, chi-squared test.

More than 100 transfected cells in each group were quantified in (D) and (K). Scale bars, 3 μm (C, F-I, and J). See also Figure S5.

Since the removal of C-I30-u in PINK1;clbn flies (Figure 3B) correlated with increased ATP production (Figure S3A), assembly of C-I30-u into C-I might inhibit C-I activity. To test this, we made a C-I30-u mimetic (C-I30-CAT-tail) containing C-term (Ala-Thr [AT])23 repeats. Expression of C-I30-CAT-tail reduced ATP production and C-I activity compared to C-I30-WT, C-I30 with a shorter AT tail, or C-I30 with a similar length but non-AT tail (Figures S5B–S5D and 5B). Moreover, mitochondria from C-I30-FLAG transfected cells also showed mildly reduced C-I activity and ATP production compared to control cells (Figures S5C and S5D). C-I30 seems to be very stringent on its C terminus such that even the FLAG tag partially interferes with its function and causes mitochondrial stress. This may explain the low level C-I30-FLAG-u formation in nontreated HeLa cells. In the case of C-I30-CAT-tail, its toxicity already efficiently activated MISTERMINATE in the absence of CCCP, and CCCP did not cause a further increase of CTE (Figure S5B).

C-I30-u Forms Aggregates and Alters Proteostasis in a CTE-Dependent Manner

When allowed to persist, CAT-tailed GFP formed aggregate in the cytosol of yeast cells (Choe et al., 2016). To test whether C-I30-u forms aggregates in mammalian cells, we examined the localization of C-I30-FLAG. C-I30-FLAG transfected cells exhibited a FLAG localization pattern similar to that of the MOM protein TOM20 under normal conditions (Figure 5C), consistent with mitochondrial inner membrane (IMM) localization of C-I30. Concomitant with the induction of C-I30-FLAG-u by CCCP, prominent FLAG+ aggregates formed (Figures 5C and 5D). CCCP did not induce aggregation of GFP-FLAG (Figure S5E). Aggregates formed by endogenous C-I30 could also be observed in HeLa cells treated with CCCP (Figure S5F). While smaller aggregates tended to co-localize with mitochondria, larger aggregates were mainly cytosolic (Figure 5C). The larger aggregates are likely cytosolic assemblies of C-I30-u released from the MOM where it was synthesized. In HeLa (GFP-Parkin) cells where C-I30-u was restricted to a lower level, C-I30 aggregation was much less pronounced (Figures S5G and S5H).

We next examined proteins associated with C-I30-u aggregates. Using cross-linking followed by fractionation to separate soluble proteins from insoluble aggregates, we enriched for CCCP-induced C-I30-u and then performed coIP. Chaperones (e.g., nascent peptide-associated complex [NAC] subunit BTF3 and Hsp70) and QC factors (p62) showed increased association with C-I30-u (Figure 5E). NAC normally binds to ribosomes to promote NPC folding, but under stress, it may move to protein aggregates and function as chaperone (Preissler and Deuerling, 2012). We also found metastable proteins, including eIF4G and eRF1 (Olzscha et al., 2011), in the aggregates (Figure 5E). Consistent with C-I30-u being synthesized on the split 60S subunit, 60S ribosomal proteins showed preferential association with C-I30-u (Figure 5E). Confocal microscopy validated localization of these factors in C-I30-u aggregates (Figures 5F–5I). Further supporting C-I30-u forming aggregates through the CTE, C-I30-(AT)23 formed aggregates even in the absence of mitochondrial stress (Figures 5J, 5K, and S5B), whereas WT C-I30-FLAG formed aggregates to a much lesser extent and only after CCCP treatment (Figure S5I). C-I30-u induction by CCCP increased the level of p-eIF2α, a marker of integrated stress response (Pakos-Zebrucka et al., 2016), and activated the Hippo-LATS-YAP signaling pathway known to be regulated by proteotoxicity (Meriin et al., 2018), indicating that CTE-mediated aggregation perturbs proteostasis (Figure S5J).

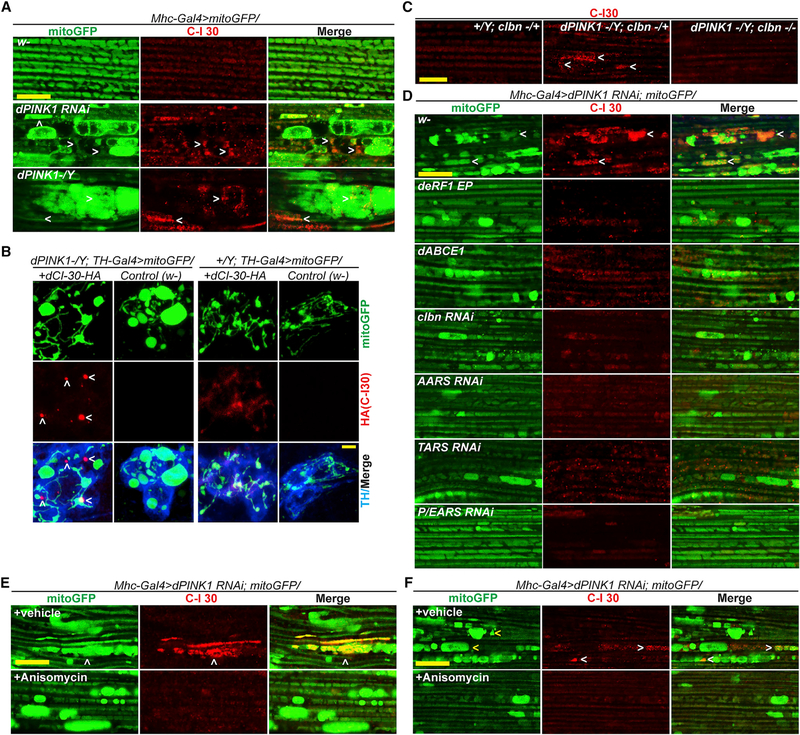

In muscle tissue of PINK1, but not WT, flies, endogenous C-I30 formed aggregates (Figure 6A). In DA neurons, transgenic C-I30-HA also formed aggregates specifically in PINK1 flies (Figure 6B). clbn markedly suppressed C-I30 aggregation (Figure 6C). Together with the removal of C-I30-u by clbn, these results support that C-I30-u is the source of aggregation. Consistently, OE of eRF1 or ABCE1, knockdown of ARSs involved in CTE, or treating cells with anisomycin, conditions that inhibited C-I30-u formation, all prevented C-I30 aggregation (Figures 6D and 6E). Moreover, while shorter-term anisomycin treatment removed C-I30 aggregates without rescuing mitochondrial morphology (Figure 6E), presumably due to differential rates of turnover of protein aggregates and aberrant mitochondria, longer treatment removed C-I30 aggregates and partially restored mitochondrial morphology (Figure 6F), supporting C-I30-u aggregation being causal of mitochondrial toxicity. Knockdown of eRF1, ABCE1, and the ARSs not involved in CTE or clbn-OE did not further modify C-I30 aggregation (Figure S6A). Anisomycin also removed C-I30 aggregates in VCP DN, hMfn1-OE, and UPF3 RNAi flies (Figures S6B and S6C). C-I30 with CTE thus is prone to aggregation and causes proteostasis failure if not adequately removed.

Figure 6. C-I30-u Forms Aggregates in Fly Neuromuscular Tissues.

(A) Immunostaining showing C-I30 aggregates in PINK1 muscle.

(B) Immunostaining showing HA+ aggregates in PINK1 DA neurons expressing C-I30-HA.

(C) Immunostaining showing effect of clbn on C-I30 aggregation in PINK1 muscle.

(D) Immunostaining showing effect of genetic manipulations on mitochondrial morphology and C-I30 aggregation in PINK1 RNAi fly muscle.

(E and F) Short-term (1 day; E) or long-term (7 days; F) anisomycin treatment on C-I30 aggregation and mitochondrial morphology in PINK1 RNAi fly muscle. Scale bars, 5 μm. Arrowheads indicate CI-30 aggregates. See also Figure S6.

Mechanisms of C-I30-u Formation in Mammalian Cells

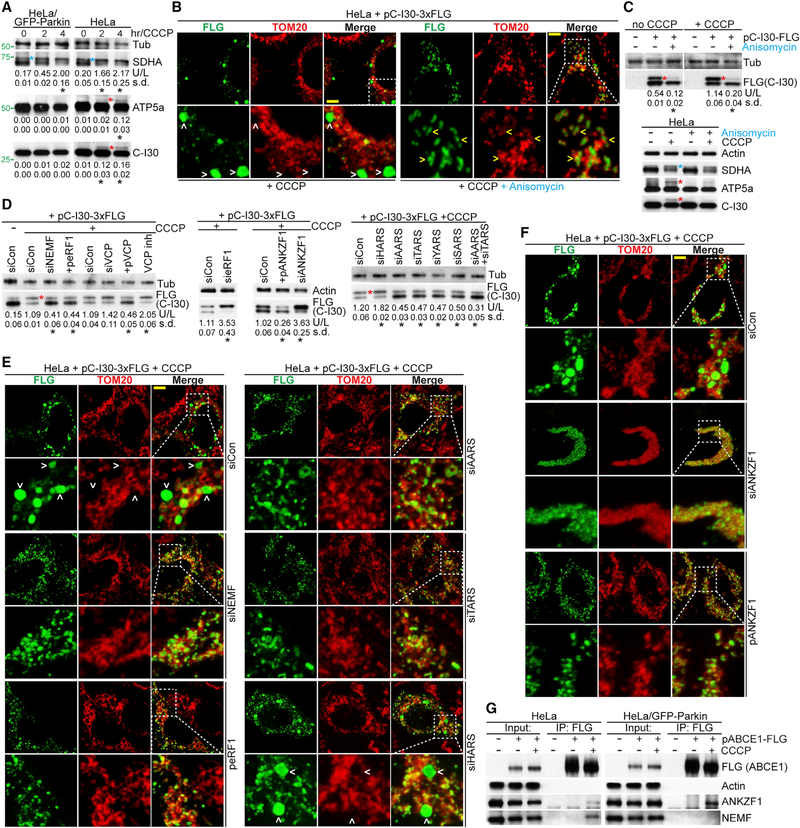

The induction of C-I30-u and C-I30 aggregation by mitochondrial stress in mammalian cells prompted us to study the mechanisms involved. Both C-I30 and ATP5a mRNAs are translated on the MOM in mammalian cells (Gehrke et al., 2015). Endogenous C-I30 and ATP5a both underwent CTE (Figure 7A) and aggregation (Figure S7A) upon CCCP treatment of HeLa cells. Anisomycin could reduce the CTE of the endogenous proteins and the CTE and aggregation of transfected C-I30-FLAG (Figures 7B, 7C, and S7B). CTE and aggregation of ATP5a were also seen in PINK1 flies (Figures S7C and S7D), and ATP5a-u seemed to be under the control of similar QC factors that regulate C-I30-u (Figure S7E).

Figure 7. Mechanism of C-I30-u Formation and Aggregation in Human Cells.

(A) Immunoblots showing induction of C-I30-U and ATP5a-u (red asterisk) in HeLa, but not HeLa (GFP-Parkin), cells. Blue asterisk indicates a succinate dehydrogenase subunit A (SDHA) form not responding to CCCP or Parkin and is likely SDHA preprotein.

(B) Immunostaining showing effect of anisomycin on CCCP-induced C-I30-FLAG aggregation. Arrowheads indicate aggregates outside (white) or inside (yellow) mitochondria.

(C) Immunoblots showing the effect of anisomycin on the CTE (red asterisk) of C-I30-FLAG (upper panel) or endogenous ATP5a and C-I30 (lower panel). Blue asterisk indicates SDHA preprotein not responding to anisomycin.

(D) Immunoblots showing effects of various modifiers or VCP inhibitor on C-I30-FLAG-u levels.

(E) Immunostaining showing effects of various modifiers on CCCP-induced FLAG+ aggregates. Arrowheads indicate aggregates.

(F) Immunostaining showing effects of ANKZF1 RNAi or OE on C-I30-FLAG aggregation.

(G) CoIP assay showing effect of Parkin on the interaction of ANKZF1 or NEMF with ABCE1.

Scale bars, 3 mm (B, E, and F). See also Figure S7.

We next tested the molecular players involved. RNAi of nuclear export mediator factor (NEMF), the mammalian homolog of Tae2 or Clbn, reduced C-I30-u formation and C-I30 aggregation (Figures 7D, 7E, and S7F). eRF1- or ABCE1-OE also reduced C-I30-u levels and C-I30 aggregation (Figures 7D, 7E, S7F, and S7G). Similar effects were observed on ATP5a-u (Figure S7H). VCP negatively regulated C-I30-u, as its OE reduced whereas its inhibition by RNAi or a small-molecule inhibitor increased C-I30-u (Figure 7D). Moreover, attenuating the co-translational import of C-I30 by Tom20 or Tom40 RNAi also promoted C-I30-u formation (Figure S7I), supporting the notion that translational slowdown or stalling due to the inefficient mitochondrial import of NPCs can be the trigger of MISTERMINATE.

Knockdown of A, T, Y, or SARS, but not HARS, significantly reduced C-I30-u levels and aggregation (Figures 7D, 7E, and S7F), in keeping with select aa being chosen for CTE. An interaction between NEMF, AARS, and TARS was seen upon CCCP treatment (Figure S7J), supporting engagement of the CTE process. In the case of C-I30-AT23, inhibition of CTE also reduced its aggregation (Figures S7K and S7L), suggesting that even without external stress, C-I30-AT23 underwent MISTERMINATE, and the additional CTE contributed to its aggregation.

We next tested the role of ANKZF1 in C-I30-u formation. Vms1 or ANKZF1 inhibits the CAT-tailing process (Izawa et al., 2017), at least in part by cleaving the peptidyl-tRNA bond (Verma et al., 2018; Kuroha et al., 2018). ANKZF1 RNAi promoted, whereas its OE inhibited, C-I30-u formation (Figure 7D). Strikingly, ANKZF1 RNAi resulted in C-I30 and C-I30-u largely accumulating on the MOM, without cytosolic aggregation (Figure 7F), suggesting a role for ANKZF1 in the release of C-I30-u from the MOM. This result further supported the MOM as the site of C-I30 and C-I30-u synthesis. ANKZF1 and NEMF interacted with ABCE1 in HeLa cells, and Parkin strengthened ABCE1-ANKZF1 but weakened ABCE1-NEMF interactions (Figure 7G). Parkin promoted the recruitment of ANKZF1 and eRF1 but inhibited that of NEMF to the MOM-associated 60S ribosome in CCCP-treated cells (Figure S7M). Moreover, C-I30-u was specifically found on MOM-associated 60S ribosomes in HeLa cells (Figure S7M). These results further support that C-I30-u is made by a CTE process and implicate a key regulatory role of Parkin. Finally, we tested the relevance of our findingsto human disease. We found increased C-I30-u and ATP5a-u and increased insolubility of C-I30 (Figure S7N) in aged PINK1 and Parkin patient fibroblasts compared to fibroblasts from matched control subjects.

DISCUSSION

Timely removal of aberrant proteins is critical for cellular health. A number of major human diseases exhibit disease-defining protein aggregates. The mechanism of protein aggregate formation has not been clearly defined. Our results demonstrate that defects in co-translational QC can lead to aberrant protein accumulation, aggregation, and proteotoxicity in vivo in settings relevant to disease. Mitochondrial stress impairs translation termination fidelity and impinges on co-translational QC, mechanistically linking mitochondrial dysfunction with proteostasis failure, two cardinal features of neurodegenerative disease.

C-I30 and Possibly ATP5a Are Endogenous Metazoan Proteins Modified by a CTE Process

Artificial templates have been instrumental in previous RQC studies. Before this study, CAT-tailing was observed in yeast on non-stop reporter proteins, where CAT tails were heterogeneous in length and composed exclusively of A and T (Shen et al., 2015). No native yeast protein is known to be CAT-tailed.

Shared features between C-I30 CTE in metazoans and CAT-tailing in yeast include dependency on RQC2, regulation by VCP and Vms1-ANKZF1, non-templated elongation, preferential incorporation of A and T, and sensitivity to anisomycin. Distinct features of C-I30-u CTE include the use of aa other than A and T, modification of a full-length protein, and induction by eRF1-ABCE1 impairment caused by mitochondrial stress. The mechanism underlying aa selectivity is currently unknown.

C-I30-u can be assembled into C-I, leading to impaired OxPhos. Moreover, it forms extra-mitochondrial aggregates and perturbs proteostasis. C-I30-u does not seem to be ubiquitinated. This is likely due to inability of the RQC system to access ubiquitination sites, because C-I30 undergoes co-translational import such that its K residues are shielded from E3 ligases by the 60S ribosome-TOM complex. Other mechanisms, such as Vms1-ANKZF1-mediated cleavage of stalled peptidyl-tRNA (Verma et al., 2018), may play more important roles in MOM-associated RQC, consistent with our data (Figure 7).

Linking Mitochondrial Dysfunction with CTE-Induced Neurodegeneration

Our results indicate that once C-I30-u escapes the surveillance of RQC, it has the potential to form cytosolic aggregates. Such aggregates may attract other aggregation-prone proteins to form disease-specific aggregates. A “seeding” mechanism, in which a cascade of molecular events link mitochondrial dysfunction to proteostasis failure, mediated by CTE-initiated sequestration and aggregation of metastable proteins, may underlie CTE-induced neurodegeneration.

Our studies identify eRF1-ABCE1 as key factors transducing mitochondrial stress signals to the RQC machinery during MISTERMINATE. Yeast eRF3 (Sup35) can form prion aggregates [PSI+] (Glover et al., 1997), which sequesters WT eRF3 away from its normal function. However, the formation of [PSI+] is a rare event even under stress, and there is no indication that metazoan eRF3 can exist in a prion state. We did not find obvious alteration of eRF3 during stress. Instead, we saw reduced eRF1 and ABCE1 and possible proteolytic cleavage of eRF1. ABCE1 is an iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster protein. Fe-S association is essential for ABCE1 function (Alhebshi et al., 2012), and the Fe-S domain of ABCE1 interacts with the C-term domain of eRF1 (Preis et al., 2014). Thus, ABCE1 may be part of the translation machinery that senses mitochondrial health. Indeed, we showed ABCE1 ubiquitination under mitochondrial stress (Wu et al., 2018), and at least in yeast cells, the WT level of ABCE1 is below the threshold sufficient for complete ribosome recycling (Young et al., 2015). ABCE1 is innately metastable and prone to sequestration by disease-associated aggregates (Olzscha et al., 2011). Sequestration of ABCE1 by CTE-induced aggregates may form a positive feedback loop that causes RQC failure. The regulation of the ABCE1-eRF1 interaction by Parkin indicates a multifaceted role of the PINK1-Parkin pathway in MOM-associated translation.

These results highlight the importance of translation termination-ribosome recycling in co-translational QC. A common step in various types of co-translational QC is splitting of stalled ribosomes before the clearance of NPCs (Schuller and Green, 2017). Whether a CTE process is involved in handling all 60S-associated NPCs remains to be seen. The eukaryotic release factors (eRFs) are involved in resolving more than one type of stalled ribosomes. During NMD, SMG1 and UPF1 interact eRF1 or eRF3 to form the SURF complex, which interacts with the exon junction complex (EJC) to trigger degradation of PTC-containing mRNAs. The faulty NPCs are also degraded during NMD (Kuroha et al., 2009), but the mechanism is poorly understood. Two EJC components, UPF3 and Y14, act as strong suppressors of C-I30-u formation. UPF3 knockdown is sufficient to induce C-I30-u and phenocopy PINK1 mutant, which can be rescued by eRF1-OE. UPF3 is shown to interact with eRFs (Neu-Yilik et al., 2017). Further studies will test the mechanism of UPF3 action in MISTERMINATE.

Involvement of Co-translational QC in Disease

Our discovery of C-I30 MISTERMINATE was led by the fortuitous observation of an aberrant form of C-I30 in the fly PINK1 PD model. This emphasizes the importance of RQC to mitochondria biology and PD. PINK1 is extensively studied as a key regulator of mitochondrial QC, particularly in mitophagy (Pickrell and Youle, 2015). Our recent studies reveal that RQC and mitophagy are mechanistically linked, representing different steps in a continuum of organelle QC (Wu et al., 2018). Inefficient RQC may lead to accumulation of C-I30-u and possibly other CTE-carrying proteins such as ATP5a-u, which, if not timely removed from the MOM, can result in activation of UPS and autophagy machineries and eventual mitophagy. A corollary of our finding is that neuronal degeneration caused by defective co-translational QC (Chu et al., 2009; Ishimura et al., 2014) may involve mitochondrial dysfunction. While MISTERMINATE may explain the intimate link between mitochondrial dysfunction and proteostasis failure, a fundamental question is whether the accumulation of CTE forms of many cellular proteins is needed, or that a selective few (e.g., C-I30-u and ATP5A-u) is sufficient, to cause neurodegeneration.

Due to the heavy burdens imposed on cellular QC systems by genomic alterations and increased protein synthesis in cancer cells, proteostasis is also highly relevant to cancer biology. Mitochondrial alterations are common in cancer cells (Deshaies, 2014), and there is evidence implicating various RQC factors in cancer (Tian et al., 2016; Fessart et al., 2013), including Rqc2 or Clbn (Wang et al., 2013b).

Our results suggest that mitochondrial diseases, long thought to arise from defective bioenergetics, could include proteostasis failure as key disease mechanism; conversely, prevalent protein-aggregation diseases could involve altered mitochondrial function. The RQC pathway may offer new therapeutic targets. In particular, Rqc2, Clbn, or NEMF offer an attractive drug target given its essential role in MISTERMINATE and the protective effect of its inactivation in a PD model. Further investigation into the cause of eRF1-ABCE1 deficiency under stress may also lead to therapeutic strategies that boost activities of eRF1-ABCE1 or other QC factors.

STAR★METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents may be obtained from the Lead Contact, Bingwei Lu (bingwei@stanford.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Drosophila stocks

The dPINK1B9 mutant was a gift from Dr. Jongkeong Chung. dparkin1 and dparkinΔ21 mutants were from Dr. Patrik Verstreken. THGal4 was a gift from Dr. Serge Birman. UAS-mito-GFP was from Dr. William Saxton. UAS-dPINK1 RNAi was generated in our lab (Gehrke et al., 2015). UAS-dVCP WT, dVCP RNAi and UAS-dVCP DN were gifts from Dr. Paul Taylor. UASp-Pelo was kindly provided by Dr. Rongwen Xi. UAS-dNOT4-myc (M) and UAS-NOT4 (W) were from Dr. Mika Rämet. clbn+/− and UAS-clbn flies were described before (Wang et al., 2013b). UAS-hMfn1 was a gift from Dr. GW 2nd Dorn. UAS-dDrp1 DN was generated in our lab.

dABCE1-HA (F001097) and dC-I30-HA (F003000) were obtained from FlyORF. dPelo RNAi (v108606), dNOT4 RNAi (v110472), dAARS RNAi (v17171), dTARS RNAi (v7752), dGARS RNAi (v106748), dHARS RNAi (v104672), dMARS RNAi (v106493), dVARS RNAi (v21782), dQARS RNAi (v101761), dP/EARS RNAi (v34995), dLARS RNAi (v45048), dSARS RNAi (v41928), dYARS RNAi (v105615), dRARS RNAi (v42185), dFARS RNAi (v107079), dWARS RNAi (v107049), dCARS RNAi (v45611), dND-SGDH RNAi (v11381, v101385), dATPsynC RNAi (#57705), blw RNAi (v34663) and deRF3 RNAi (v106240) were from the VDRC. dC-I30 RNAi (#44535, #51425), dNOT4 EP (#22246), dABCE1 RNAi (#31601), dY14 EP (#6597), dY14 RNAi (#55367), deRF1 EP (#17265), deRF1 RNAi (#67900), deRF1KY7 mutant (#7069), deRF3 EP (#20740), deRF3LR17 mutant (#7067), UAS-GFP-dUPF1 (#24623), dUPF1 RNAi (#64519), dUPF3 EP (#16558), dUPF3 RNAi (#44565), dXRN1 EP (#33263), dXRN1 RNAi (#34690), dATPsynO RNAi (#43265) and dKARS RNAi (#32967) and other general fly stocks were from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center.

Unless otherwise indicated in the figure legend, male flies at 2–3 weeks of age were used for the experimental procedures described. Fly culture and crosses were performed according to standard procedures and raised at indicated temperatures. Flies were generally raised at 25°C and with 12/12 hr dark/light cycles. Fly food was prepared with a standard receipt (Water, 17 L; Agar, 93 g; Cornmeal, 1,716 g; Brewer’s yeast extract, 310 g; Sucrose, 517 g; Dextrose, 1033 g).

Cell lines

Regular HeLa cells and PINK1 (−/−) HeLa cells (a gift from Dr. Richard Youle, NINDS) were cultured under normal conditions (1× DMEM medium, 8.75% FBS, 5% CO2,37°C). HeLa/GFP-Parkin cells (a gift from Dr. Yuzuru Imai, Juntendo University) were cultured with drug selection (1mg/ml puromycin). The HeLa cell line was derived from cervical cancer cells taken from a female patient who died of cancer.

METHOD DETAILS

Drosophila behavior tests and ATP measurement

For all wing posture assays, male flies at 7-day and 14–15-day old and aged at 29°C were used. 20 male flies were collected/raised in one vial and 3 independent vials were counted per genotype. Measurements of ATP contents in thoracic muscle were performed as described previously (Gehrke et al., 2015), using a luciferase-based bioluminescence assay (ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kit HS II, Roche Applied Science). For each test, three thoraces were dissected by removing heads, wings, legs and abdomen from whole flies, and the remaining part quickly homogenized in 100 μl lysis buffer. The tissue lysates were then boiled for 5 min at 100°C and briefly cleared by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 2 mins. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and kept on ice. 2.5 μl of cleared tissue lysate was-mixed with 187.5 μl dilution buffer and 10 μl luciferase reagent.The luminescence signal wasimmediately measured by a Lumat LB 9507 tube luminometer (Berthold Technologies). For each genotype or drug treatment group, at least 3~4 independent tests were assayed.

Fly muscle and brain staining

For immunohistochemical analysis of mitochondrial morphology of adult fly brains and muscle tissues, 5-day old male flies from 29°C were assayed. In muscle staining, at least 5 individuals were examined for each genotype and the representative images were presented. For analysis of DA neuron number in the various genetic backgrounds, 21-day old male flies were assayed. In DA neuron staining, at least 7 individuals were examined for each genotype. Dissected tissue samples were briefly washed with 1 × PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde in 1 × PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes at room temperature. Fixatives were subsequently blocked with 1 × PBS containing 5% normal goat serum and incubatedfor 1 hour at room temperature followed by incubation with primary antibodiesat 4°Covernight.The primary antibodies used were: chicken anti-GFP (1:5,000, Abcam), rat anti-HA (1:1,000; Sigma), rabbit anti-TH (1:1000, Pel-Freez), mouse anti-C-I30 (1:1,000, Abcam) and mouse anti-ATP5a (1,1000, Abcam). After three washing steps with 1× PBS/0.25% Triton X-100 each for 15 minutes at room temperature, the samples were incubated with Alexa Fluor® 594-conjugated, Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated, and Alexa Fluor® 633-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500, Molecular Probes) for 3 hours at room temperature and subsequently mounted in SlowFade Gold (Invitrogen).

Cell lines, cell culture and cell transfection conditions

Regular HeLa cells and PINK1−/− HeLa cells (a gift from Dr. Richard Youle, NINDS) were cultured under normal conditions (1× DMEM medium, 8.75% FBS, 5% CO2, 37°C). HeLa/GFP-Parkin cells (a gift from Dr. Yuzuru Imai, Juntendo University) were cultured in the same condition with additional drug selection (1μg/ml puromycin).

Cell transfections were performed by using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (cat#: L3000015, Invitrogen) and knocking-down experiments were performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (cat#: 13778150, Invitrogen), according to instructions from the manufacturers. Stealth RNAi siRNAs (Invitrogen) used for the RNAi experiments are: CNOT4 (HSS107246, HSS107245), ABCE1 (HSS109286, HSS109285), siRNAs: siCON (cat#:12935–400, Invitrogen), siNEMF (NEMFHSS113541, NEMFHSS113540), siVCP (VCPHSS111263, VCPHSS111264), siHARS (HARSHSS104694), siAARS (AARSHSS100022), siTARS (TARSHSS110482), siYRAS (YARSHSS112540), siSARS (SARSHSS109468) from Invitrogen Inc.

Immunohistochemical analysis of cultured cells

For immunohistochemical analysis in human cells, the HeLa cells were cultured on the ethanol-cleaned cover glass. Cells were washed with 1×PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde in 1× PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature, later washed and permeabilized with 1× PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes. The fixed samples were subsequently blocked with 1× PBS containing 5% normal goat serum and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature followed by incubation with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used were mouse anti-Flag (1:1,000, Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-Flag (1:1,000, Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-TOM20 (1:1,000, Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-BTF3 (1:500, Abcam), guinea pig anti-P62 (1:500, ProGEN), mouse anti-RpS6 (1:500, Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-RpL3 (1:500, Cell Signaling), mouse anti-ATP5a (1:1,000, Abcam) and mouse anti-SDHA (1:1,000, Abcam). The secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor® 488, 594 and 633-conjugated antibodies (1:500, Molecular Probes).

Drug treatments

For drug treatment of Drosophila, flies were collected after eclosion and divided into separate vials (20~25 flies each vial). Instant fly food (Carolina) was mixed with 1% H2O2 (cat#: H1009, Sigma-Aldrich), 250 μM rotenone (cat#: R8875, Sigma-Aldrich) or 100 μM CCCP (cat#: C2759, Sigma-Aldrich). Vials were changed every day. Samples were collected for further analyses after 5 days of treatment. In order to achieve high efficiency, anisomycin stock (100mM in DMSO, cat#: A9789, Sigma-Aldrich) were diluted with the Schneider’s Medium (cat#: 21720–024, GIBCO™) to 250 μM and injected into fly thorax between mesonotum and scutellum via a hand-made glass needle. After injection, flies were kept in the vial with standard fly food and waited for 24 hours (short-term) before the experiments, and for long-term (7 days) treatment, three injections (day0, day3, day6) were applied to newly eclosed flies.

For drug treatment in human cells, HeLa cells or HeLa/GFP-Parkin cells were cultured and treated with CCCP at the indicated concentrations and durations as described (Narendra et al., 2010). For most experiments, 20 μM CCCP concentration was used. For Antimycin/Oligomycin treatment, 10 μM of each compound was used. For anisomycin, 200 μM was used, and for the VCP inhibitor NMS-873 (cat#: S7285, Selleckchem), 1 μM was used.

SDS-PAGE sample preparing, gel preparing and running conditions

Home-made gels

The home-made Laemmli resolving gel (10 ml) contains 3 mL of 40% Acrylamide/Bis (cat#: 1610148, Bio-Rad), 2.5 mL of 1.5M Tris-HCl pH 8.8 (cat#: 1610798, Bio-Rad), 1 mL of 10% SDS (cat#: 1610416, Bio-Rad), 50 μl of 10% APS (cat#: 1610700, Bio-Rad) and 5 μl of TEMED (cat#: 1610800, Bio-Rad). The stacking gel (2.5 ml) contains 0.25 mL of 40% Acrylamide/ Bis, 0.63 mL of 0.5M Tris-HCl pH 6.8 (cat#: 1610799, Bio-Rad), 250 μl of 10% SDS, 12.5 μl of 10% APS and 2.5 μl of TEMED. The running buffer (1L) contains 3g Tris base (cat#: 11814273001, Sigma-Aldrich), 14.4g Glycine (cat#: G8898, Sigma-Aldrich), and 1g SDS (cat#: L3771, Sigma-Aldrich).

Commercial gels

NuPAGE 4%−12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels (cat#: NP0321BOX, Invitrogen) and NuPAGE® MOPS SDS running buffer (cat#: NP0001, Invitrogen) was used for SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses. NativePAGETM 3%−12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels (cat#: BN1001BOX, Invitrogen) and NativePAGE Running Buffer Kit (cat#: BN2007, Invitrogen) were used for Native-PAGE as the first dimension of the 2-D gel. The gel slices were cut and denatured by heating in the 1× Laemmli SDS sample buffer for 10 minutes and then load to Home-made SDS-PAGE for the second dimension.

Western blotting and antibodies

The primary antibodies used for western blot analyses were presented in the Key Resources Table section.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | INDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Chicken anti-GFP | Abcam | ab13970 |

| Rabbit anti-TH | Pel-Freez | P40101-150 |

| anti-TOM20 | Santa Cruz Biotech | sc-17764, sc-11415 |

| Rabbit anti-NDUFV1 | Novus Biologicals | NBP1-33074 |

| Mouse anti-Opa1 | Novus Biologicals | NBP1-71656 |

| Rabbit anti-Mfn2 | Sigma-Aldrich | M6319 |

| Mouse anti-Cytochrome C | Abcam | ab110325 |

| Mouse anti-ATP5a [15H4C4] | Abcam | ab14748 |

| Mouse anti-SDHA | Abcam | Ab14745 |

| Mouse anti-C-IV s.1 | Abcam | ab14705 |

| Mouse anti-C-I 30 | Abcam | ab14711 |

| Mouse anti-UQCRC2 | Abcam | ab14745 |

| Mouse anti-Actin | Sigma-Aldrich | A2066 |

| Mouse anti-Tubulin | Thermo Fisher | MA 1-80017 |

| anti-FLAG | Sigma-Aldrich | F1804, F7425 |

| Rat anti-HA | Sigma-Aldrich | 11867423001 |

| Rabbit anti-eRF1 | Cell Signaling Biotech | 13916S |

| Rabbit anti-eRF3 | Cell Signaling Biotech | 14980S |

| Rabbit anti-Hsp90 | Selleckchem | A5015 |

| Mouse anti-Hsp60 | Santa Cruz | sc-59567 |

| Rabbit anti-Hsp70 | Selleckchem | A5002 |

| Rabbit anti-BTF3 | Abcam | ab66940 |

| Mouse anti-p62 | Abcam | ab56416 |

| Rabbit anti-eIF4G | Cell Signaling Biotech | 2498S |

| Rabbit anti-RpL7a | Cell Signaling Biotech | 2415S |

| Mouse anti-RpS6 | Cell Signaling Biotech | 2317S |

| Rabbit anti-RpL3 | Santa Cruz | sc-86828 |

| Rabbit anti-pS51-eIF2α | Cell Signaling Biotech | 9721S |

| Rabbit anti-eIF2α | Cell Signaling Biotech | 9722S |

| Rabbit anti-pS127-YAP | Cell Signaling Biotech | 13008T |

| Mouse anti-NEMF | Invitrogen | MA5-27473 |

| Mouse anti-ANKZF1 | Santa Cruz | sc-398713 |

| Rabbit anti-ABCE1 | Dr. R Hegde | N/A |

| Rabbit anti-Pelo | Abcam | ab140615 |

| Mouse anti-AARS | Sigma-Aldrich | SAB1405414 |

| Rabbit anti-TARS | Sigma-Aldrich | SAB2702096 |

| Mouse anti-MARS | Sigma-Aldrich | SAB1409302 |

| Rabbit anti-Clbn | Dr. Bi | N/A |

| Goat anti-Rabbit secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 594 | Invitrogen | R-37117 |

| Goat anti-Chicken secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | Invitrogen | A-11039 |

| Goat anti-Mouse secondary antibody, Alexa Flour 633 | Invitrogen | A-21052 |

| Goat anti-Mouse secondary antibody, Alexa Flour 488 | Invitrogen | A-28175 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG-HRP | Santa Cruz | sc-2005 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG HRP | Santa Cruz | sc-2004 |

| Goat anti-Rat AffiniPure IgG HRP | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 112-035-003 |

| Goat Anti-Chicken IgY HRP | Abcam | ab97135 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant proteins | ||

| H2O2 | Sigma-Aldrich | H1009-100ML |

| Rotenone | Sigma-Aldrich | R8875-1G |

| CCCP | Sigma-Aldrich | C2759-100MG |

| Anisomycin | Sigma-Aldrich | A9789-100MG |

| Cycloheximide | Sigma-Aldrich | C7698-1G |

| Puromycin | Sigma-Aldrich | P7255-100MG |

| Antimycin A | Sigma-Aldrich | A8674-100MG |

| Oligomycin A | Sigma-Aldrich | 75351-5MG |

| NMS-873 | Selleckchem | S7285 |

| Lipofectamine 3000 | Invitrogen | L3000015 |

| Lipofectamine RNAiMAX | Invitrogen | 13778150 |

| Percoll | GE Healthcare | 17089101 |

| EDTA | Sigma-Aldrich | E9884-100G |

| EGTA | Sigma-Aldrich | E3889-100G |

| 40% Acrylamide/Bis buffer | Bio-Rad | 1610148 |

| 1.5M Tris-HCl pH 8.8 buffer | Bio-Rad | 1610798 |

| 0.5M Tris-HCl pH 6.8 buffer | Bio-Rad | 1610799 |

| 10% SDS solution | Bio-Rad | 1610416 |

| 10% APS solution | Bio-Rad | 1610700 |

| TEMED | Bio-Rad | 1610800 |

| Tris base | Sigma-Aldrich | 11814273001 |

| Glycine | Sigma-Aldrich | G8898 |

| SDS | Sigma-Aldrich | L3771 |

| SUPERase· In | Invitrogen | AM2694 |

| Protease inhibitor cocktail | Bimake | B14012 |

| PMSF | Thermo Fisher | 36978 |

| Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail | Bimake | N15001 |

| Anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel | Sigma-Aldrich | A2220-5ML |

| Normal goat serum | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 005-000-121 |

| 3 × FLAG tag peptide | APExBIO | A6001 |

| Pierce 16% Formaldehyde (w/v), Methanol-free | Thermo Fisher | 28908 |

| Triton™ X-100 | Sigma Aldrich | T9284-100ML |

| 5% Digtonin | Invitrogen | BN2008 |

| DMEM, high glucose, GlutaMAX Supplement | GIBCO | 10566016 |

| Schneider’s Medium | GIBCO | 21720-024 |

| Critical Commercial Assays and Services | ||

| ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kit HS II | Roche | 11699709001 |

| Complex I Enzyme Activity Microplate Assay Kit | Abcam | ab109721 |

| Protease K digestion kit | Thermo Fisher | AM2548 |

| CIP phosphatase kit | NEB | M0290S |

| USP reaction kit | BostonBiochem | E-504 |

| Enterokinase reaction kit | NEB | P8070S |

| ProTEV Plus reaction kit | Promega Inc. | V6101 |

| RNeasy Mini kit | QIAGEN | 74104 |

| OneStep RT-PCR kit | QIAGEN | 210212 |

| NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels | Invitrogen | NP0321 BOX |

| NuPAGE® MOPS SDS running buffers | Invitrogen | NP0001 |

| NativePAGETM 3-12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels | Invitrogen | BN1001BOX |

| NativePAGE Running Buffer Kit | Invitrogen | BN2007 |

| Western Lightning Plus-ECL | PerkinElmer Inc. | NEL105001EA |

| HyBlot CL® Autoradiography Film | Denville Scientific Inc. | 1159M38 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Stealth RNAi siRNA Negative Control Hi GC | Invitrogen | 12935-400 |

| Stealth RNAi™ siRNA of CNOT4 | Invitrogen | HSS107246, HSS107245 |

| Stealth RNAi™ siRNA of ABCE1 | Invitrogen | HSS109285, HSS109286 |

| Stealth RNAi™ siRNA of NEMF | Invitrogen | HSS113541, HSS113540 |

| Stealth RNAi™ siRNA of VCP | Invitrogen | HSS111263, HSS111264 |

| Stealth RNAi™ siRNA of HARS | Invitrogen | HSS104694 |

| Stealth RNAi™ siRNA of AARS | Invitrogen | HSS100022 |

| Stealth RNAi™ siRNA of TARS | Invitrogen | HSS110482 |

| Stealth RNAi™ siRNA of YARS | Invitrogen | HSS112540 |

| Stealth RNAi™ siRNA of SARS | Invitrogen | HSS109468 |

| Oligonucleotides for RT-PCR, see Table S3 | N/A | |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG | This study | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-TEV | This study | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-TEV-FLG | This study | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-AT5 | This study | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-AT23 | This study | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30(mMTS)-FLG (36R→A) | This study | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-Astop | This study | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-AKstop | This study | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-AKKstop | This study | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+)-HA-C-I30-FLG | This study | N/A |

| pCMV-FLAG-ABCE1 | Dr. Ramanujan Hegde | N/A |

| pCMV6-FLAG-NOT4 | OriGene Inc. | RC217418 |

| pCMV6-ANKZF1 | OriGene Inc. | RC201054 |

| pCMV-SPORT6.1-eRF1 | DharmaconTM | MHS6278-202804766 |

| pCMV-SPORT6.1-VCP | DharmaconTM | MHS6278-202760239 |

| Experimental Models: Drosophila Stocks | ||

| See Experimental Model and Subject Details | N/A | |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| HeLa cell | Dr. Richard Youle | N/A |

| PINK1 (−/−) HeLa cell | Dr. Richard Youle | N/A |

| HeLa/GFP-Parkin cell | Dr. Yuzuru Imai | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Byonic v 2.14.27 | Protein Metrics Inc. | N/A |

| Thermo Proteome Discoverer (v 1.4.1.14) | Thermo Fisher Inc. | N/A |

To prepare insoluble fractions from human patient fibroblasts for western blotting, cell lysates were mixed with 2× Laemmli SDS sample buffer (1× as final concentration) and denatured by boiling at 100°C for 10 minutes. The insoluble fraction was pelleted via ultra-high-speed centrifugation (100,000 rpm, TLA 120.2 Rotor, 60 min, 4°C). After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer, mixed with 4× Laemmli SDS sample buffer (2× as final concentration) and analyzed by immunoblotting.

To obtain quantitative western blot results, experimental conditions such as the amounts of protein loaded, the antibody dilutions, and exposure times were adjusted to make sure that the western blot signals were in the linear range. For western blots, analyses were performed using standard protocols. After incubation with the ECL reagent (cat# NEL105001EA, PerkinElmer Inc.), the signals were recorded on X-ray film (cat# E3018, Denville Scientific Inc.), scanned, and signal intensity analyzed by ImageJ. For all the blots used in the manuscript, at least three biological repeats were assayed, and the typical ones were presented. The numbers under the blots represent the ratio of presented blot. The statistical analyses in Figures 2J and 3G and S2E were based on data from three independent biological repeats.

Co-IP experiments

For C-I30-u immunoprecipitation, we transiently expressed pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I 30-FLG-TEV plasmici in HeLa cells. Sixty hours post-transfection, we applied UV cross-linking and 0.5% formaldehyde in 1× PBS to the attached cells on the Petri dish. We homogenized the cells in the lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.4,150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1mg/ml cycloheximide, 1× RNase inhibitor, and Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (cat#: B14012, Bimake)], additional Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (cat#: B15001, Bimake) will be applied if phosphorylation signal is to be detected. After centrifugation at 10,000 g for 5 min, the supernatant was subjected to immunoprecipitation using the indicated antibodies, or affinity gels (Anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel, cat#: A2220, Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C for 6 hours with gentle shaking. Subsequently, the Sepharose beads were washed three times (10 minutes each) at 4°C in lysis buffer, mixed with 2× SDS Sample buffer, and loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels.

Mitochondria, mitochondria-associated ribosome purification, proteinase protection assay, and CI-30-u purification and C-I activity measurement

Intact mitochondria from in vitro cell cultures and fly muscle tissue samples were purified and quality controlled for the absence of contamination by other organelles as described previously (Gehrke et al., 2015). For analysis of fly samples, male flies at appropriate ages were used for thoracic muscle dissection. To block the release of mRNAs associated with mitochondria, 0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide was applied to all buffer solutions. Samples were homogenized using a Dounce homogenizer. After two steps of centrifugation (1,500 g and 13,000 g), the mitochondria pellet was washed twice with HBS buffer (5 mM HEPES, 70 mM sucrose, 210 mM mannitol, 1 mM EGTA, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail), then resuspended and loaded onto Percoll gradients. The fraction between the 22% and 50% Percoll gradients containing intact mitochondria were carefully transferred into a new reaction tube, mixed with 1 volume of HBS buffer, and centrifuged again at 20,000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C to collect the samples for further analyses. The mitochondria then were solubilized by 5% Digtonin (cat#: BN2006, Invitrogen) on ice for 30 min and prepared as the sample for Blue Native PAGE using the NativePAGE™ Sample PreP Kit (cat#: BN2008, Invitrogen), or solubilized for C-I30-u purification.

For denature immunoprecipitation of fly C-I30-u, partially purified mitochondria sample was first extracted by mitochondrial lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4,150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 0.1mg/ml cycloheximide, 1× RNase inhibitor, and Complete protease inhibitor cocktail) on ice for 15 minutes, and the remaining pellets were prepared by solubilization with 1× SDS Sample buffer. The samples were denatured by boiling at 100°C, and then diluted with pre-chilled lysis buffer at a 1:5 ratio and subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-CI-30 (cat#: ab14711, Abcam).

Complex-I activity was measured using the Complex I Enzyme Activity Microplate Assay Kit (cat# ab109721, Abcam) and following the manufacturer’s protocol. 200 μg of purified mitochondrial sample was used in each measurement. The colorimetric signals were read using the Epoch plate reader (BioTek, USA).

For mitochondrial ribosomal fraction purification, briefly, purified mitochondria from human cells were lysed with Buffer A (20 mM HEPES, 50 mM KCl and 10 mM MgCl2) with additional 0.1% Triton X-100,0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide and 1× RNase Inhibitor. The mitochondrial lysate was pre-cleared by centrifugation (20,000 g, 10 min, 4°C), and then loaded onto a 25% sucrose cushion (made in Buffer A). The ribosome fraction was pelleted via high-speed centrifugation (70,000 rpm, TLA 100.3 Rotor, 20 min, 4°C). After centrifugation, the ribosomal pellet was resuspended in Buffer A containing 1% Triton X-100 and analyzed by immunoblotting.

For proteinase K digestions, purified intact mitochondria were suspended in either isotonic mitochondrial HBS buffer or osmotic buffer (1 volume of HBS plus 5 volumes of 5 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.2). Mitochondrial suspensions were rotated gently for 30 minutes on ice prior to proteinase K digestion. For detergent-permeabilized mitochondria, Triton X-100 was added to HBS suspended samples from 20% (v/v) stock to a final concentration of 1%; 5 minutes before proteinase K incubations began. Samples of intact, osmotic shocked, and detergent-permeabilized mitochondria were then treated with proteinase K (cat# AM2548; Thermo Fisher) at concentrations of 5 μg/ml for 30 minutes on ice. Digestion was terminated with 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, cat# 36978; Thermo Fisher). Mitochondrial proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by western blotting with indicated antibodies.

Trypsin partial digestion and Mass Spec

C-I30 IP samples were combined and run on a 4%−12% SDS-PAGE gel and resolved protein bands stained by Coomassie blue R-250 staining. Protein bands were excised out into a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and then cut into 1×1 mm squares. The excised gel pieces were then reduced with 5 mM DTT, 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate at 55°C for 30 min. Residual solvent was removed and alkylation was performed using 10 mM acrylamide in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate for 30 min at room temperature. The gel pieces were rinsed 2 times with 50% acetonitrile, 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and placed in a speed vac for 5 min. Digestion was performed with Trypsin/LysC (Promega) in the presence of 0.02% protease max (Promega) in both a standard overnight digest at 37°C as well as in a limited digest format (2 hours at 50°C). Samples from both digestion conditions were combined to one tube, centrifuged and the solvent including peptides were collected and further peptide extraction was performed by the addition of 60% acetonitrile, 39.9% water, 0.1% formic acid and incubation for 10–15 min. The peptide pools were dried in a speed vac. Samples were reconstituted in 12.5μl reconstitution buffer (2% acetonitrile with 0.1% Formic acid) and 3μl (100ng) of it was injected into the instrument.

LC/MS data of the trypsin-Partially-digested peptides were collected on an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) with a Nanoacquity M Class UPLC (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). For a typical experiment, a flow rate of either 300 nL/min or 450 nL/min was used, where mobile phase A was 0.2% formio acid in water and mobile phase B was 0.2% formio acid in acetonitrile. Analytical columns were prepared in-house with an I.D. of 100 microns pulled to a nanospray emitter using a P2000 laser puller (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA). The column was packed using C18 reprosil Pur 2.4 μM (Dr. Maisch) to a length of ~25cm. Peptides were directly injected onto the analytical column using a linear gradient (4%−40% B) of 80min. The mass spectrometer was operated in a data dependent fashion using CID fragmentation for MS/MS spectra generation collected in the ion trap with a collisional energy of 35%.

Customized database searches

For the Generic Database Searches

In a typical LCMS data analysis, the .RAW data files were processed using Byonic v 2.14.27 (Protein Metrics, San Carlos, CA) to identify peptides and infer proteins. Proteolysis was assumed to be semi-tryptic with up to four missed cleavage sites. Precursor mass accuracies were held within 12 ppm, and 0.4 Da for MS/MS fragments. Proteins were held to a false discovery rateof 1%, using standard approaches (Elias and Gygi, 2007). Resulting peptides were then investigated for potential modification using either wildcard search conditions, or modified .fasta files including potential peptide sequences of interest (see text).

For the Customized Database Searches

Raw data were analyzed using the Thermo Proteome Discoverer computational software (version 1.4.1.14) with Sequest HT as search engine. A precursor mass tolerance was set to ± 12 ppm and a fragment mass tolerance of ± 0.8 Da. We allowed up to 4 missed tryptic cleavages for trypsin semi-digestion. The maximum false peptide discovery rate was specified as 1% (FDR < 0.01). The resulting peptide files were searched against in-house peptide sequencing pools, based on our finding of ARS-dependency of C-I30-u formation. Identified peptides were filtered for high confidence, a search engine rank of 1 and peptide mass derivation of 7 ppm. All the peptide assignments with interest were also manually validated. The proteomics data can be accessed via ProteomeXchange (PXD*). The source code (requiring Python environment) to generate the in-house peptide sequencing pools will be available upon request.

Plasmids and molecular cloning

The original human C-I30 CDS sequence was from the pPM-N-D-C-His (PV394217, abm) plasmid. pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG and pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-TEV plasmids were generated by cloning the human C-I30 CDS with different tags into pcDNA3.1(+) vector via KpnI and Xba I sites.

pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-TEV-FLG; pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-AT5; pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-AT23; pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-non-AT25; pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30(mMTS)-FLG (36R/A); pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-Astop; pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-AKstop; pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-AKKstop and pcDNA3.1(+)-HA-C-I30-FLG; were modified based on the pcDNA3.1(+)-C-I30-FLG-TEV plasmid via the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (cat#: E0554S, NEB). pCMV-FLAG-ABCE1 was a gift from Dr. Ramanujan Hegde. pCMV6-FLAG-NOT4 and pCMV6-ANKZF1 was obtained from OriGene Inc (cat#: RC217418 and RC201054 TrueORF). pCMV-SPORT6.1-eRF1 (cat#: MHS6278–202804766, DharmaconTM) and pCMV-SPORT6.1-VCP (cat#: MHS6278–202760239, DharmaconTM) were from GE healthcare. All plasmids have been confirmed by sequencing.

CLIP assay and tRNA RT-PCR

CLIP assays were performed as we described before (Gehrke et al., 2015). Briefly, we placed the fly lysates on ice and performed UV cross-linking using a Stratalinker 2000. We then performed regular IP, washed the beads and added 2×SDS buffer to the beads as usual. Samples were loaded onto 12% SDS-PAGE gel and prepared for WB. After WB, we cut out a small section from the PVDF membrane covering the expected protein position of Clbn. We prepared 4mg/ml proteinase K in 1×PBS and add 30ul to the cut out membrane, incubated 20min at 37°C. We then extracted RNA from the membrane strip by following manufacturer’s manual of the RNA extraction kit (RNeasy kit, cat# 74104, QIAGEN) by adding 100ul of RLT+ β-mercaptoethanol. We used a homogenizer to enhance RNA removal from the membrane. We then used the purified RNA samples for RT-PCR with the OneStep RT-PCR kit (cat# 210210, QIAGEN).

The following primers were used in RT-PCR analyses to detect fly tRNAs from the CLIP assay: RT-tRNA(Ala_AGC)-N: GGGGATGTAGCTCAGATG;

RT-tRNA(Ala_AGC)-C: TGGAGATGCGGGGTATCG;

RT-tRNA(Ala_CGC)-N: GGGGACGTAGCTCAGTG;

RT-tRNA(Ala_CGC)-C: TGGAGACGCCGGGGTTT;

RT-tRNA(Ala_TGC)-N: GGGGATGTAGCTCAGTGG;

RT-tRNA(Ala_TGC)-C: TGGAGATGCCGGGGATCG;

RT-tRNA(Thr_AGT)-N: GGCGCCGTGGCTTAGTT;

RT-tRNA(Thr_AGT)-C: AGGCCCCGGCGAGATTC;

RT-tRNA(Thr_CGT)-N: GCCTCTTTAGCTCAGTGG;

RT-tRNA(Thr_CGT)-C: TGCCTCCTGTGAGGGTTG;

RT-tRNA(Thr_TGT)-N: GCCTCTTTAGCTCAGTGG;

RT-tRNA(Thr_TGT)-C: TGCCTCCTGTGAGGATTG;

RT-tRNA(Ser_CGA)-N: GCAGTCGTGGCCGAGTG;

RT-tRNA(Ser_CGA)-C: CGCAGCCGGTAGGATTCG;

RT-tRNA(Ser_AGA)-N: GCAGTCGTGGCCGAGCG;

RT-tRNA(Ser_AGA)-C: CGCAGTCGGTAGGATTCG;

RT-tRNA(Ser_TGA)-N: GCTGCGGTGTCCGAGTG;

RT-tRNA(Ser_TGA)-C: CGCTGCGGACAGGACTTG.

PPTase, USP2 treatment, Enterokinase digestión and TEV Digestion

For Phosphatase reaction, the purified C-I30-Flag protein (30μl beads) was digested on beads (Anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel) with final 10U CIP Phosphatase (cat#: M0290S, NEB) in the 1× CIP buffer (50 mM Potassium Acetate, 20 mM Tris-acetate, 10 mM Magnesium Acetate, 100 ug/ml BSA, pH 7.9 at 25°C). The reaction was performed for 30 minutes at 37°C with gentle shaking.

For USP2 reaction, the purified C-I30-Flag protein (30μl beads) was pre-equilibrated with 1× DUB reaction buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl and 5 mM DTT) and digested on beads (Anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel). USP2 was diluted in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl and 2 mM DTT buffer and pre-incubated for 10 min at 22C. Subsequently, each sample was incubated with pre-incubated 3 μM USP2 (cat#: E-504, Boston Biochem) for different time points (0.5, 1 and 2 hours) at 37°C with gentle shaking.

For Enterokinase digestion, the purified C-I30-Flag protein (30μl beads) was digested on beads (Anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel) with final 5U Enterokinase (cat#: P8070S, NEB) in the 1× EK reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2 pH 8.0). The reaction was performed for 16 hours to balance the efficiency and specificity at 22°C with gentle shaking.

For TEV digestion, the purified C-I30-Flag protein (30μl beads) was digested on beads (Anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel) with 10U ProTEV Plus (cat#: V6101, Promega) in the 1× ProTEV digestion buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.0,0.5 mM EDTA). The reaction was performed for 6 hours to achieve the maximal efficiency at 30°C with gentle shaking.

After reaction, the supernatant was separated from the beads via centrifugation. Beads were washed once with 1× PBS. The samples were mixed with 2× SDS sample buffer and denatured by heating, and then loaded for western blot analyses.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All analyses were performed with SPSS (IBM, USA) and further confirmed by MATLAB (MathWorks, USA). Error bars represent standard deviation (s.d.). Data in Figures 5D and 5K and Figure S5H, S7D and S7F were analyzed by Chi-square test. For pairwise comparisonsin Figure 3E, S3A, S4C, S4E weusedtwo-tailedStudent’sttest. Forcomparing multiple groups as in Figure S1C, 2E, 2H, 2J, S2F, 3G, S4E, 5B, S5C and S5D we used one-way ANOVA test followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test (or SNKtest) plus Bonferroni correction (multiple hypotheses correction). In our statistical comparisons, * indicating p < 0.05 and ** indicating p < 0.01 were considered as significant differences. Sample size/statistical details were stated separately in the figure legends.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

Raw data have been deposited to Mendeley Data and are available at https://doi.org/10.17632/cctkk3hg3h.1.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Longer forms of respiratory chain proteins accumulate under mitochondrial stress

Such proteins are formed by co-translational C-terminal extension (MISTERMINATE)

Such proteins can impair respiratory chain and also form cytosolic aggregates

MISTERMINATE links mitochondrial dysfunction with proteostasis failure in disease

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS