Abstract

Dual-acting virucidal entry inhibitors (DAVEIs) have previously been shown to cause irreversible inactivation of HIV-1 Env-presenting pseudovirus by lytic membrane transformation. This study examined whether this transformation could be generalized to include membranes of Env-presenting cells. Flow cytometry was used to analyze HEK293T cells transiently transfected with increasing amounts of DNA encoding JRFL Env, loaded with calcein dye, and treated with serial dilutions of microvirin (Q831K/M83R)-DAVEI. Comparing calcein retention against intact Env expression (via Ab 35O22) on individual cells revealed effects proportional to Env expression. “Low-Env” cells experienced transient poration and calcein leakage, while “high-Env” cells were killed. The cell-killing effect was confirmed with an independent mitochondrial activity-based cell viability assay, showing dose-dependent cytotoxicity in response to DAVEI treatment. Transfection with increasing quantities of Env DNA showed further shifts toward “High-Env” expression and cytotoxicity, further reinforcing the Env dependence of the observed effect. Controls with unlinked DAVEI components showed no effect on calcein leakage or cell viability, confirming a requirement for covalently linked DAVEI compounds to achieve Env transformation. These data demonstrate that the metastability of Env is an intrinsic property of the transmembrane protein complex and can be perturbed to cause membrane disruption in both virus and cell contexts.

Graphical Abstract

More than 30 years since its initial recognition as the causative agent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and despite campaigns for HIV-1 awareness, treatment, and prevention, HIV-1 infection has persisted globally, with 2 million new infections per year.1,2 The primary and most effective tool so far in controlling HIV-1 infection has been combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), a tuned drug cocktail targeting multiple steps of the viral life cycle. According to the recommendations of the World Health Organization, front-line ART should consist of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and one non-nucleo-side reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) or one integrase inhibitor (INSTI), typically a fixed dose combination of tenofovir (NRTI), lamivudine (NRTI), and efavirenz (NNRTI).3 However, a limitation of cART is that all of the inhibitor components of reverse transcriptase or integrase act after entry of the virus into the target cell and must be in the target cell simultaneously with the viral RNA. Entry inhibitors, a developing class of anti-HIV treatments, may instead be able to intervene earlier, targeting virus directly at the externally presented viral Env protein complex before cell entry.4,5

Env is the sole surface protein of HIV-1 and is responsible for its interactions with target CD4-positive cells that lead to entry and infection. The Env glycoprotein complex is composed of a trimer of dimers, each a cleaved and folded combination of gp120 and the transmembrane gp41. As such, targeting and inactivating this protein complex could provide an important means of controlling HIV infection and progression. This has led us to investigate the potential to trigger conformational rearrangements and inactivating responses based on the known metastability of the Env protein complex. Previous strategies for Env targeting have focused primarily on gp1206–10 and the six-helix bundle region of gp41.11–13 Nonetheless, some efforts have been aimed at the highly conserved membrane proximal external region (MPER) of gp41, which is at the base of the gp41 ectodomain, partially buried in the membrane, and has been the target of several broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1.14–16 Further more, the literature has reported the MPER as being capable of stimulating lipid mixing in cholesterol rich membranes,17 as well as fusion in lipid vesicles18 and reconstituted lipid monolayers recovered from infectious HIV particles,19 underscoring its importance and function in mediating HIV infectivity.

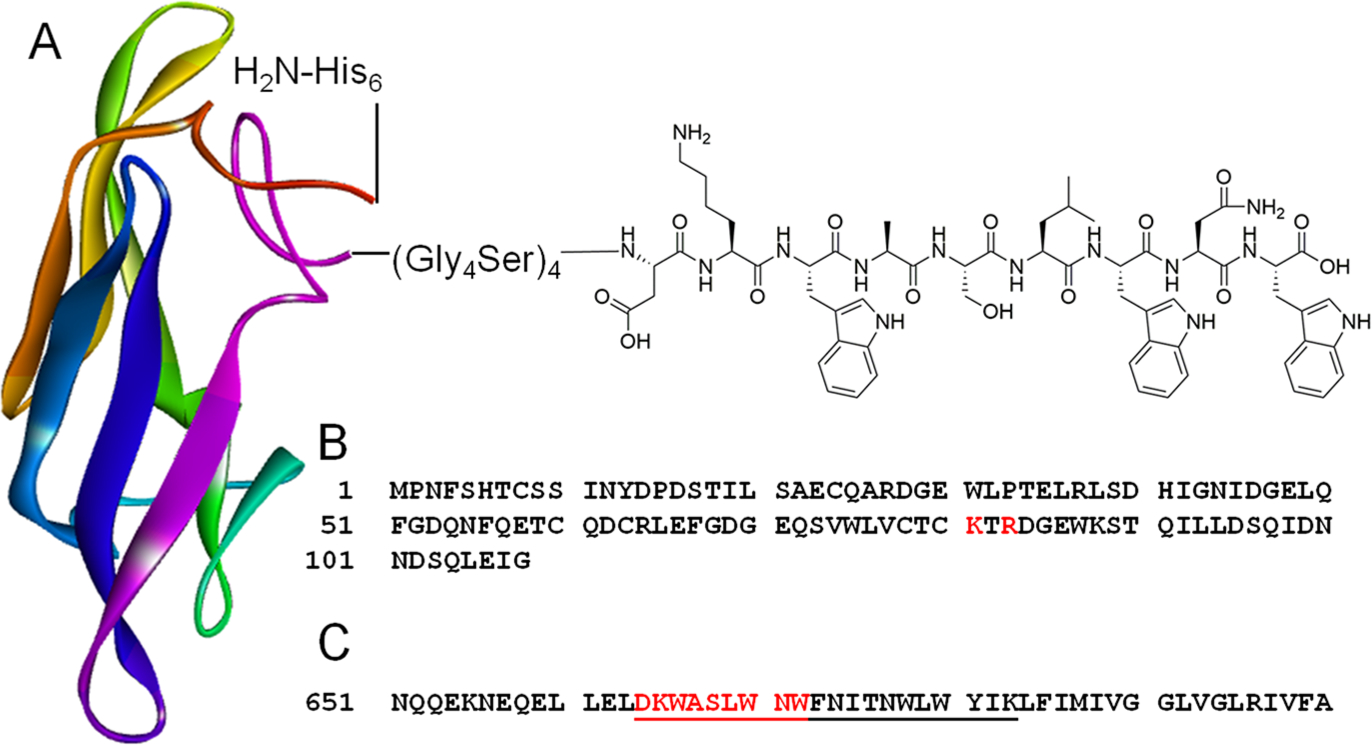

On the basis of the information presented above, we previously established a class of anti-HIV-1 entry inhibitors called DAVEIs (dual-acting virucidal entry inhibitors), containing components that inhibit HIV-1 infection and inactivate HIV-1 virions by interacting with two sites in HIV-1 Env, one composed of gp120 glycans and a second in gp41, to cause radical membrane disruption in viruses and consequent irreversible virus inactivation.20–22 A current-generation DAVEI compound is MVN*-L4-Trp3 [M*DAVEI, M*D (see Figure 1A)], a reengineered lectin DAVEI.22 MVN* is a recombinant variant of the original lectin microvirin (MVN), containing Q81K and M83R mutations (Figure 1B) that enhance MNV’s ability to bind to mannose-α (1–2)-mannose terminating glycans on HIV-1 Env gp120 and has been shown to inhibit HIV-1 infection.23,24 L4 describes the flexible peptide linker (G4S)4. Trp3 is a truncation of the HIV-1 Env membrane proximal external region (MPER) sequence at the third tryptophan [HxBc numbering 664–672 (see Figure 1C)], resulting in the peptide sequence DKWASLWNW.22

Figure 1.

Structural representation of the M*DAVEI inhibitor. (A) Schematic depiction of the lectin DAVEI, starting from the N-terminus and containing hexahistidine, microvirin (Q51K/M53R), the (G4S)4 linker, and Trp3. The microvirin protein shown is Protein Data Bank entry 2Y1S23 visualized with BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer version 19.1 (B) Sequence of the microvirin (Q51K/M53R) protein, with mutations colored red. (C) Excerpted sequence (residues 651–700) of HIV-1 Env, with MPER underlined and the Trp3 sequence (residues 664–672) colored red.

While the inactivating activity of M*DAVEI was initially defined as a virolytic process occurring with pseudovirus membranes,22 a fundamental question that remained unsolved was whether the underlying activity originated in the metastability of the Env protein complex. We therefore asked whether the membrane disruption effect of DAVEIs can be generalized to any biological membrane in which the Env has been embedded, as opposed to only specific and stressed virus and pseudovirus membranes. In the work reported here, we examined this question by testing the hypothesis that M*DAVEI membrane disruption can be applied to cells presenting Env and that induced poration of the lipid bilayer results from the Env glycoprotein and the membrane bilayer acting as a combined metastable unit driven by the metastability of the Env protein. We investigated this by means of HEK293T cells transiently transfected with only Env-encoding DNA, as a platform for Env and membrane analysis. The results demonstrate such cellular effects, arguing that Env protein structural perturbations triggered by dual-site engagement can lead to changes in the integrity of the Env–membrane interface.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production and Validation of MVN*-DAVEI, MVN*, and L3-Trp3.

MVN*-DAVEI, MVN*, and L3-Trp3 were produced according to the previous MVN*-DAVEI study.22,23 Briefly, plasmids for MVN*-DAVEI and MVN* alone were transformed on Novagen Rosetta (DE3) competent cells (Millipore, Burlington, MA), plated on LB-ampicillin agar plates for 16 h at 37 °C, from which positive colonies were selected, inoculated, and subcultured to 4 L in LB-ampicillin at 37 °C. Cells were induced with isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside when the optical density was between 0.6 and 0.8, for 16 h at 16 °C while being shaken at 225 rpm. Grown cells were then pelleted, lysed, and centrifuged again to retrieve the supernatant for separation by a Ni-NTA column, followed by a Sephacryl S100 16/60 prep-grade column (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL), using AKTA FPLC. Protein eluates were assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for homogeneity.

The L3-Trp3 peptide was synthesized using a LibertyBlue microwave peptide synthesizer (CEM, Matthews, NC), using standard Fmoc chemistry on Rink amide resin, and purified to >95% homogeneity by analytical reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography on a C18 column.

Cell Preparation.

The plasmid encoding JRFL Env was a kind gift from S. Cocklin. HEK293T cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Polyethylenimine, 25 kDa linear, was obtained from Polysciences, Inc. (Warrington, PA). All other reagents, unless otherwise noted, were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH).

HEK293T cells were seeded at a density of 3 million cells per flask, transiently transfected with 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8 μg of JRFL Env plasmid DNA and 12 μg of PEI/μg of DNA, an adaptation from the pseudovirus production protocol used in prior DAVEI studies.20–22,25 Cells were detached with 5 mM EDTA in DPBS at 24 h after transfection and reseeded at a density of 10K cells per well in 96-well plates for cell viability assays or 50K cells per well in 48-well plates for flow cytometry assays.

Flow Cytometry Assays.

Mock and transfected 293T cells were incubated with 1 μM calcein acetoxymethyl-ester (Calcein AM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 30 min to load cells with fluorescent dye, washed with medium, and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C with serial dilutions of MVN*-L4-Trp3, MVN* alone, L3-Trp3 alone, MVN* and L3-Trp3 in a 1:1 mixture, or a PBS control. Cells were washed with medium and allowed to rest for 1 h in medium after treatment, so any in-progress transformations could reach completion. After resting, cells were detached with 5 mM EDTA, washed and resuspended in FC buffer [1% BSA and 1 mM EDTA in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4)], fixed with 2% fresh paraformaldehyde in PBS (15 min at room temperature), and then washed and resuspended three times. Fixed cells were then stained with Ab 35O22 (NIH AIDS Reagent Program) for 1 h at room temperature and 5 μg/mL, followed by three washes in FC buffer, incubation with secondary stain anti-Hu PerCP (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) for 1 h at room temperature, and 1:500 dilution. Cells were washed a final three times and resuspended in FC buffer before cell counts, retained fluorescence (green), and Env staining (red) were assessed in counted cells on a Guava EasyCyte 5HT flow cytometry system (Millipore). Analyzed cells were subject to forward/side scatter gating based on untreated control populations of identical transfection, and median fluorescence values were obtained using Guava InCyte 3.2 software. Data were plotted using OriginPro 8 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) and modeled using a logistic fit regression to produce dose–response curves and/or analyzed using ANOVA in OriginPro 8 to calculate p values among cell populations.

Cell Viability.

Mock and transfected 293T cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C with serial dilutions of MVN*-L4-Trp3 or a PBS control. Cells were then washed with medium and then incubated with 10% WST-1 Cell Proliferation Reagent (Takara Bio USA, Mountain View, CA) in medium for 1 h, before measurement of the absorbance at 450 nm using a Tecan (Männedorf, Switzerland) Infinite F50 plate reader, indicative of mitochondrial activity and cell viability.

RESULTS

Treatment with M*DAVEI Causes Intracellular Loss of Dye from Transfected Env-Presenting Cells.

Env-presenting cells were derived by modifying the protocol25 used previously to produce pseudovirus by transfection of HEK293T cells with only the Env-encoding plasmid (omitting the NL4–3 capsid core plasmid). On the basis of the known synthesis and trafficking pathways of Env, no processing or modification of the Env trimer itself should occur between transit to the cell surface and budding off onto virus particles.19,26 We evaluated whether membrane disruption could occur with cell-presenting Env, analogously to virus-presenting Env. To address this possibility, we established a cellular dye leakage assay. Calcein AM in its initial state is both membrane permeable and nonfluorescent but, upon cleavage by intracellular esterases into free calcein, becomes both membrane impermeable and highly fluorescent.27 Transfected and nontransfected cells were preincubated for 30 min with 1 μM calcein AM for cells to take up and cleave the dye. Cells were then incubated with the indicated concentrations of M*DAVEI for 18 h at 37 °C, before washing, plate detachment, fixation with 2% paraformaldehyde, Env staining with Ab 35O22 and anti-human IgG-PerCP, and analysis by flow cytometry. Ab 35O22 was selected for its binding to the gp120–gp41 interface and used as an indicator for the presence of mature, intact Env spike.28,29

Representative dot plots are shown in Figure 2, depicting Env-dependent reductions in both the number of cells counted and calcein-associated green fluorescence as M*DAVEI concentrations were increased. This trend was observed in all transfection cases examined and was more pronounced in the cases with more Env DNA. Plots were divided into four quadrants on the basis of the distribution and fluorescence intensity of cells stained green (Y-axis; higher is indicative of calcein retention) and red (X-axis; farther right is indicative of intact Env expression), and the same quadrant divisions and gain settings were applied to all graphs (X marker at 2 × 103, Y marker at 2 × 103). The nontransfected case (top row) provides a baseline for zero Env expression (generally not exceeding X = 102) and shows a distribution of retained calcein in the untreated case (roughly 65% above the Y = 2 × 103 marker, and 35% below). As M*DAVEI treatment was applied to the nontransfected cell case, the calcein distribution did not notably change, though there was a slight decrease in the number of cells counted at the highest treatment concentration (4 μM). In the transfected cell cases, the X = 2 × 103 marker divided cells into “high-Env” (X > 2 × 103) and “low-Env” (102 < X < 2 × 103) populations. The transfection efficiency for these cells was 90–95% as determined by flow cytometry. As the level of treatment of transfected cells increased, we observed two different phenomena occur on the basis of Env expression. “Low-Env” cells appeared to show movement from high-calcein to low-calcein quadrants (i.e., shifting from top left to bottom left) as indicated by both percentage and absolute cell counts. Supporting this is the observation that the combined total of cells in both left-side quadrants of transfected cells remained relatively stable, even as M*DAVEI treatment concentrations increased (see Table 1).

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry dot plots depicting cell populations charted by calcein dye retention (Y-axis, green) and JRFL HIV-1 Env expression (X-axis, red) after MVN*DAVEI (M*D) treatment. Calcein dye on the Y-axis, 35O22 primary/PerCP secondary staining on the X-axis, on fixed cells after treatment with the indicated concentrations of M*D over 18 h. Quadrant labels show the percentage and absolute cell counts for each quadrant. Cells were gated by forward and side scatter to remove dead cells and cellular debris. Dot plots are representative for one of four independent experiments.

Table 1.

| 0 μM M*DAVEI |

0.16 μM M*DAVEI |

4 μM M*DAVEI |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 μg of Env DNA | 4756 (100%) | 4410 (−7.3%) | 4638 (−2.5%) |

| 4 μg of Env DNA | 4387 (100%) | 3943 (−10%) | 4233 (−3.5%) |

| 6 μg of Env DNA | 3365 (100%) | 3315 (−1.5%) | 3571 (6.1%) |

| 8 μg of Env DNA | 2876 (100%) | 2688 (−6.5%) | 2466 (−14%) |

Sum of cell counts in the top left and bottom left quadrants for each dot histogram in Figure 2 and the percent change in the total cell count relative to 0 μM M*DAVEI treatment.

In contrast, “high-Env” cells disappeared from the field of observation altogether as the level of M*DAVEI treatment increased, again as indicated by the absolute cell counts, although there was also some shifting from high calcein to low calcein in moderate transfection and moderate treatment cases (e.g., 2 and 4 μg transfection at 0.16 μM treatment). The sum of the right-side, “high-Env”, cell counts dropped precipitously with an increased level of M*DAVEI treatment, suggesting that “high-Env” cells were damaged or destroyed by the M*DAVEI–Env interaction (see Table 2).

Table 2.

| 0 μM M*DAVEI |

0.16 μM M*DAVEI |

4 μM M*DAVEI |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 μg of Env DNA | 17228 (100%) | 11843 (−31%) | 1879 (−89%) |

| 4 μg of Env DNA | 12326 (100%) | 9492 (−23%) | 910 (−93%) |

| 6 μg of Env DNA | 9068 (100%) | 5172 (−43%) | 1438 (−84%) |

| 8 μg of Env DNA | 5125 (100%) | 1811 (−65%) | 674 (−87%) |

Sum of cell counts in the top right and bottom right quadrants for each dot histogram in Figure 2 and percent change in total cell count relative to 0 μM M*DAVEI treatment.

In addition, the data in Figure 2 show that Env-dependent poration occurred without loss of gp120. We conclude this because dye-depleted cells could be detected by the mAb 35022, which recognizes Env-containing sequence regions from gp120, and because while the “low-Env” cell population does not decrease, neither does it increase, discounting the conversion of “high-Env”/gp120-positive cells into “low-Env”/ gp120-negative cells upon M*DAVEI treatment.

In summary, these data suggest that “low-Env” cells treated with M*DAVEI are subject to transient poration, wherein they leak fluorescent calcein but survive. In contrast, “high-Env” cells are destroyed or damaged to such an extent that they no longer appear in the gated cell population, either as debris or having undergone rounding and detachment from the plate prior to flow cytometry.

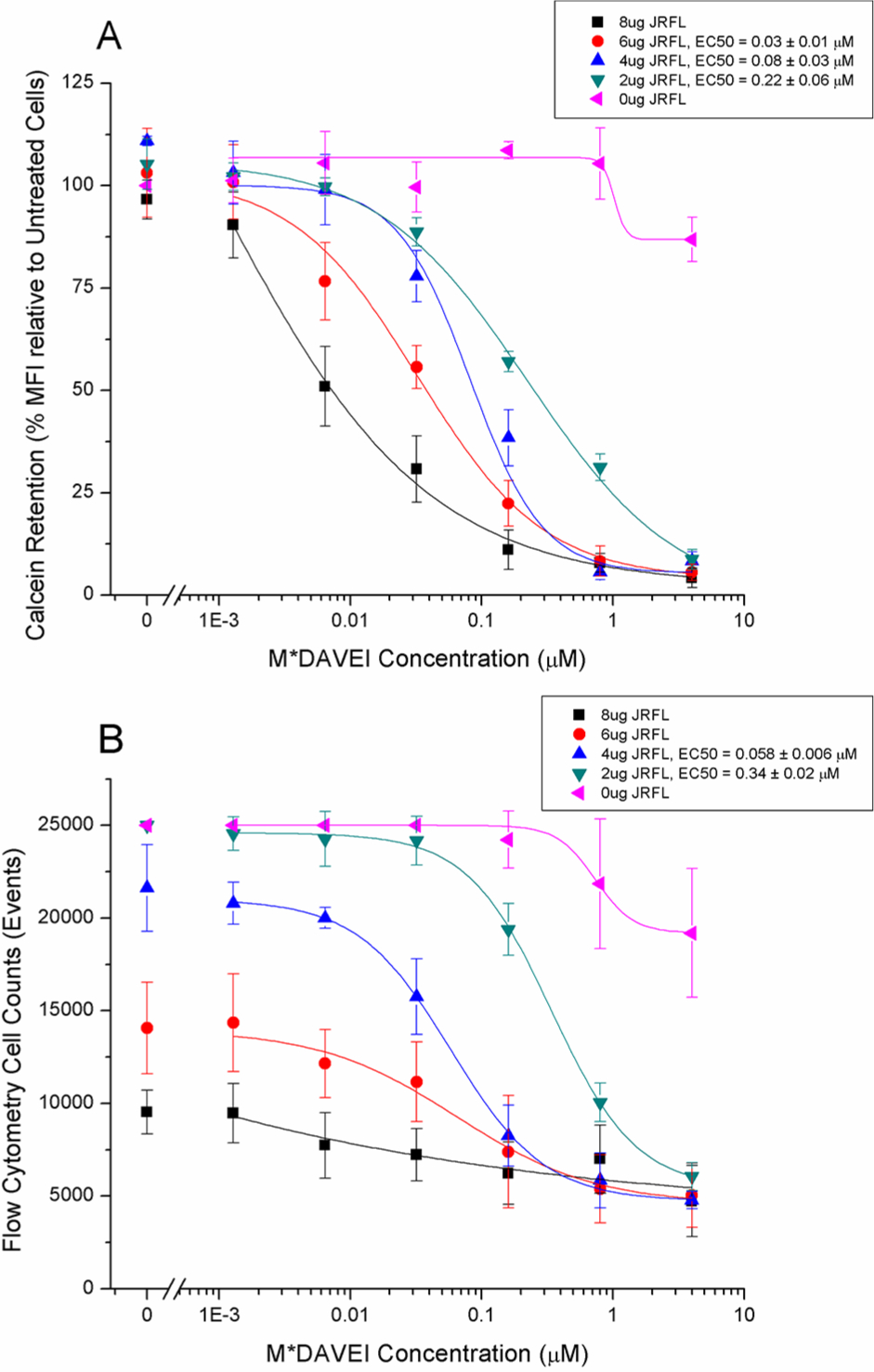

The combined flow cytometry data obtained from four repeats, and including all intermediate M*DAVEI treatment concentrations, are shown in Figure 3. Figure 3A shows, for all transfected cells, a dose-dependent, near-total loss of fluorescence based on the median fluorescent index of the green channel/calcein. Analysis and logistic curve fitting to the data suggest that as the level of Env transfection increased, so did sensitivity to M*DAVEI treatment. Notably, the loss of fluorescence described in Figure 3A applied only to cells counted by the flow cytometer in this assay. Treatment with M*DAVEI as well as transfection itself strikingly reduced the number of cells counted in this assay despite identical initial plating numbers, as graphed in Figure 3B. Although flow cytometry preparation requires several rigorous wash steps, cell losses from this should be uniform among samples, further suggesting that M*DAVEI treatment has caused an effect on the number of cells available to be analyzed at the end of this experiment.

Figure 3.

Membrane leakage and cell count effects of M*DAVEI. (A) Calcein dye retention as a percent of the median fluorescence intensity of untreated cells of the same transfection. Calcein retention values in nontreated groups were compared to those of nontransfected and nontreated populations. Fluorescence intensity is normalized for cell count and reflects the median among cells counted only. (B) Numbers of cells counted by flow cytometry for the dye retention experiment depicted in panel A. Cells were transfected with 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8 μg of HIV-1 JRFL Env gp160 DNA. Data are the average of four independent experiments. For all graphs, error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean.

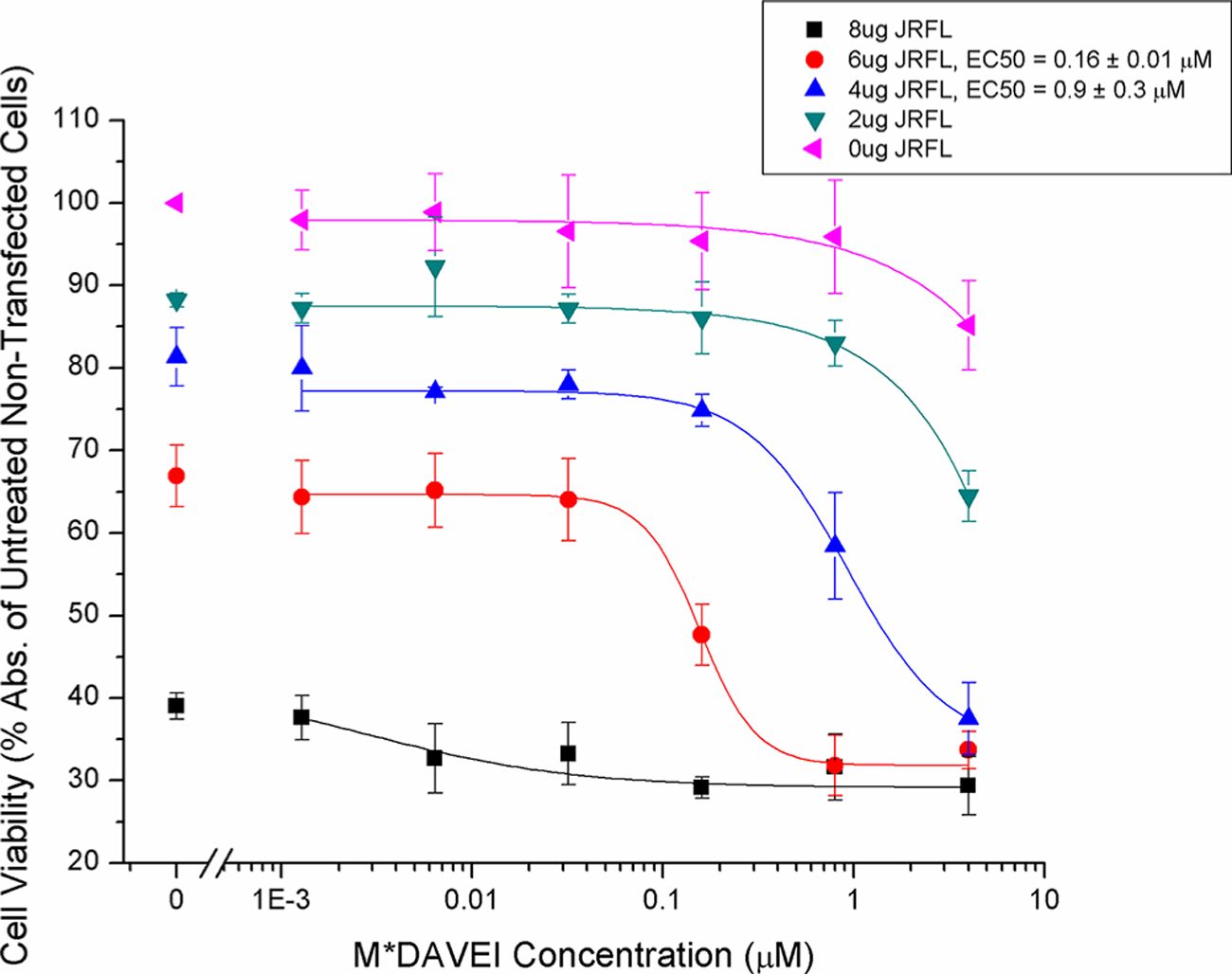

Dose-Dependent Cell Viability Loss upon Treatment with M*DAVEI.

Because the flow cytometry experiment showed dose-dependent cell losses, we proceeded to test specifically for impacts to cell viability in response to M*DAVEI treatment. We verified cell viability loss by testing directly for mitochondrial activity as detected by the WST-1 reagent (Takara), a method that does not depend on membrane intactness. As shown in Figure 4, cell viability was strongly affected by both M*DAVEI treatment and transfection load. Relative to untreated control cells (unlinked data points before the axis break), transfected cells showed dose-dependent viability losses, with cytotoxic potency increasing in cells with more Env DNA transfection. We also found a degree of nonspecific cytotoxicity in nontransfected HEK293T cells, albeit only at the highest concentration (4 μM M*DAVEI) at the extended durations tested here (18 h incubation). Interestingly, the maximum cell viability loss observed was ~70%, suggesting that ~30% of the cells remain viable, possibly due to a low level of or no Env complex expression.

Figure 4.

Cell viability detection of M*DAVEI effects on HIV-1 Env-expressing cells. Bulk cell viability was measured using WST-1 mitochondrial activity reagent. An initial 10000 transfected or nontransfected cells were seeded per well and treated with the indicated concentrations of M*DAVEI for 18 h at 37 °C. Afterward, inhibitor-containing medium was removed and immediately replaced with medium containing 10% WST-1 reagent and incubated for an additional 1 h at 37 °C. Data are the average of four independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean.

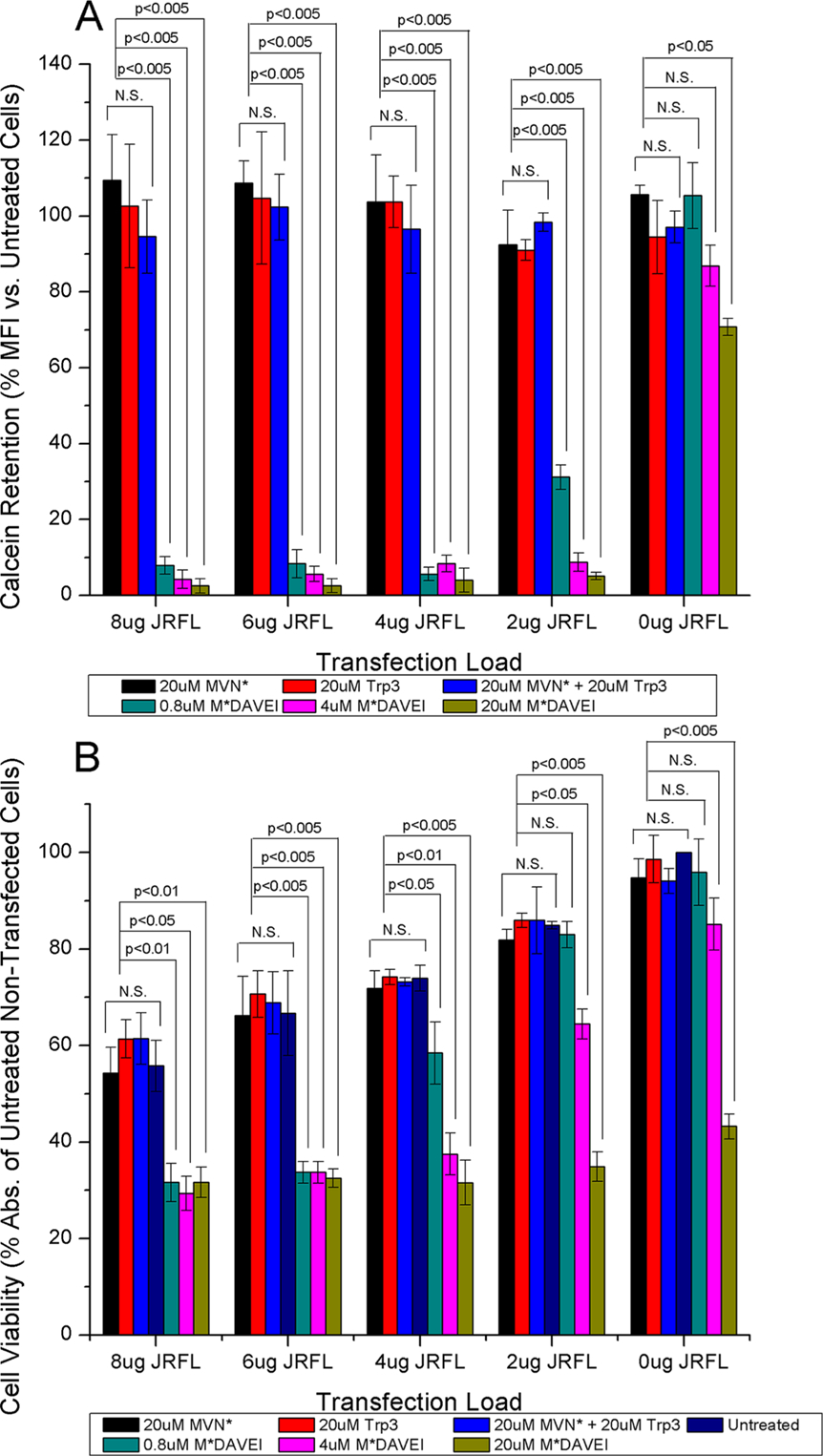

Dependence of M*DAVEI Cell Effects on Covalent Chimeric Linkage.

To validate the specificity of the leakage and loss of cell viability effects observed, individual and unlinked components of M*DAVEI were tested for the ability to cause dye leakage and loss of cell viability in transfected and nontransfected cells. Concentrations of 20 μM were selected to make any effect from individual or unlinked components readily apparent. This also served as a check on the nonspecific effects seen when nontransfected cells were treated with high concentrations of M*DAVEI, to determine if individual components of the linked molecule were responsible. Figure 5A shows that individual and unlinked components of M*DAVEI were unable to cause poration and dye leakage as elicited by the conjugated M*DAVEI construct. However, at the highest concentrations tested, M*DAVEI was able to cause some poration in nontransfected cells, though the effect was minor compared to that in Env-transfected cells.

Figure 5.

Specificity of M*DAVEI cell effects. (A) Calcein retention as the percent median fluorescence intensity relative to untreated cells at the same transfection load. No significance (p > 0.05) in calcein retention was detected between treatment with individual or unlinked components of M*DAVEI (20 μM MVN*, Trp3, or MVN*+Trp3) and untreated cells. Cells treated with linked M*DAVEI showed significant effects at multiple transfection loads; data for 0.8, 4, and 20 μM are included for comparison. (B) Cell viability as the percent absorbance at 450 nm relative to untreated, nontransfected cells. No significant loss (p > 0.05) in cell viability was detected between treatment with individual or unlinked components of M*DAVEI (20 μM MVN*, Trp3, or MVN*+Trp3) and untreated cells of the same transfection. Comparatively, cells treated with linked M*DAVEI showed significant effects at multiple transfection loads. Data for 0.8, 4, and 20 μM treatment sets are included for comparison. The significance of data was determined by ANOVA. Data are averages from three independent experiments. Error bars depict the standard deviation of the mean.

Figure 5B shows cell viability (using WST-1) of transfected and nontransfected cells in response to individual and unlinked components of M*DAVEI. Again, individual components and unlinked component mixtures had no apparent effect relative to untreated cells of the same transfection. In addition, as for dye leakage, the highest concentration of M*-DAVEI revealed cytotoxic effects with untransfected cells. Potential reasons for this off-target effect are presented in the Discussion.

To rule out the possibility that M*DAVEI cell effects resulted from nonspecific membrane weakening due to an elevated level of membrane protein expression, we performed additional control experiments (data not shown) using cells transfected with the non-Env membrane protein CD4-YFP at 0, 4, and 8 μg of DNA (the cDNA was a gift from T. Jin, Immunogenetics, Twinbrook II Facility, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Rockville, MD). Transfection with variable amounts of CD4-YFP encoding the plasmid resulted in a baseline viability reduction commensurate with the transfection load, likely due to PEI (see the Discussion). Nonetheless, treatment with M*DAVEI reduced cell viability in all transfection variants only fractionally, with minimal and irregular dose–response trends, and maximul partial loss (<30%) restricted to the highest concentrations (4 and 20 μM). We observed no dependence of this fractional M*DAVEI effect on transfection load. Furthermore, intracellular calcein was substantially retained upon M*DAVEI treatment except with a slight loss (<20%) at the highest M*DAVEI concentrations (4 and 20 μM). In all transfection cases, the sensitivity of CD4-YFP control cells to M*DAVEI did not increase with higher DNA transfection loads. This is in contrast to the observed effects of M*DAVEI upon JRFL Env-transfected cells. These results reinforce the notion that it is the metastable structure of Env that permits membrane disruption by M*DAVEI.

DISCUSSION

M*DAVEI Disrupts Env in Cell Membranes, Resulting in Poration and Loss of Cell Viability.

We asked in this work whether Env transformations associated with metastability-derived virolysis can occur generally in Env-containing membranes. Here, we have demonstrated membrane disruption in cells as being caused by an Env-dependent poration event and detected by calcein leakage. This also supports the notion that Env and the membrane act as a metastable unit, especially as consistent levels of 35O22 binding show no large-scale fusion-like rearrangements of the Env trimer proteins. Furthermore, our cell platform has been validated as a tool for mechanical investigations of Env–membrane transformations.

The Degree of Env-Specific Poration Determines Cell Fate.

While cell membrane intactness and impermeability have frequently been used to test for cell viability, the literature and now our own data have shown that this is not absolute. As the dot histograms of calcein versus Env staining showed (Figure 2), Env expression is not uniform, even within each transfection category, but had “high-Env” and “low-Env” expression populations. As described above, “low-Env” cells appeared to shift from a strong calcein signal (top left) to a weak calcein signal (bottom left) with an increasing level of M*DAVEI treatment. Free calcein is a small (622.55 Da, estimated hydrodynamic size of ~1.3 nm30) but membrane impermeable molecule, suggesting that the only way it would be removed from the cell on these time scales would be poration or permeabilization of the cell membrane (Figure 3A shows the median calcein retention drops to ~5% with sufficient M*DAVEI treatment). However, the continued presence of the cells to be counted by this assay shows that this is not an overly destructive or damaging event. In contrast, while there is some analogous shifting from high calcein (top right) to low calcein (bottom right) in the “high-Env” right-side populations, the disappearance of cells from the observable window in flow cytometry is the dominant effect. Combined with the cytotoxicity results established in Figure 4, we take this to mean that “high-Env” cells are damaged or destroyed as a result of M*DAVEI treatment.

These results reinforce the previously established22 Env dependence of M*DAVEI’s lytic effect. Env expression facilitates poration, but a certain density or abundance of surface Env appears to be necessary to enable cell damage and killing. One potential explanation is that individual pores activated by M*DAVEI may merge (either spatially or temporally) into larger membrane disruptions, sufficient to overwhelm and damage or kill the Env-presenting cell.

Studies focused on characterizing bacterial pore-forming toxins have also described the distinction between poration and cytotoxicity/cytolysis.31–33 In these studies, bulkier proteins (e.g., hemoglobin) and polydextrans were used as nonleaking size controls, while smaller molecules leaked freely, much as calcein did in our observations. The literature on repair from pore-forming toxins and mechanical rupture also argues that pores and membrane disruptions can be repaired if not too extreme, which may explain our observations in the “low-Env” cell populations. Depending on the size and source of the lesion, mechanisms for cell membrane repair include patching with intracellular membranes (e.g., vesicles and organelles, Golgi), clogging/clotting with protein aggregates, or even pinching the damaged region off of the cell membrane as in endocytosis or exocytosis.34–37 We surmise that such repair mechanisms may occur in the aftermath of the interactions of low-Env cells with M*DAVEI.

Dual Engagement of gp120 and gp41 by Covalently Linked MVN*-Trp3 Is Necessary for Poration and Cytotoxicity.

The results obtained here demonstrate that the cell-killing effects of MVN*-Trp3 depend on covalent attachment of the two functional moieties and hence that both moieties must be binding at the same time to Env. To ascertain the importance of the covalent linkage between MVN* and Trp3 components, individual components and the unlinked mixture of components were tested against the covalently linked M*DAVEI for poration and cytotoxicity. Figure 5 shows that unlinked component concentrations of ≤20 μM were unable to cause any significant poration or cytotoxicity effect in cells, demonstrating the need for dual engagement by a single chimeric molecule to achieve poration. This finding is consistent with the dual-engagement requirements of virus lysis by DAVEI compounds as investigated previously21,22 and further supports cell and virus having similar specific DAVEI effects due to having a shared target in Env.

While dual-site Env engagement underpins DAVEI function, localization of the epitopes in Env where the two components of MVN*-Trp3 DAVEI bind coordinately remains incompletely defined. Prior results for lectin MVN binding argue strongly that the MVN* domain of the DAVEI molecule binds to a cluster of glycans in the outer domain of the gp120 protein subunits of Env.23 In contrast, the site of interaction of the Trp3 domain is less understood. Because lysis requires gp41 and gp41-specific antibodies inhibit lysis, we previously concluded that the Trp3 sequence in DAVEIs binds to a sequence region in the gp41 subunit.21,22,38 Several possible sites are contained in the gp41 subunits. One possibility is that the Trp3 interaction occurs at the membrane permeable external region (MPER) of an Env trimer on the surface of a virus or infected cell.22,38 Specifically, because Trp3 is derived from the MPER sequence itself, Trp3 may be able to displace one of Env’s native MPER protomers (see Figure 6 for a schematic of this predicted event cascade) and disrupt the membrane by forcing a mixed trimer state incorporating two native Env protomers plus the DAVEI Trp3, as suggested in recently reported molecular simulation.38 Such a process would be complementary with the MPER’s apparent ability to insert into cholesterol rich membrane outer leaflets to cause fusion,17 coupling hydrophobic interactions with protein trimerization. Other models39 hypothesize an open, “tripod” configuration of MPER, which would leave both the MPER and the membrane available for Trp3 interaction.

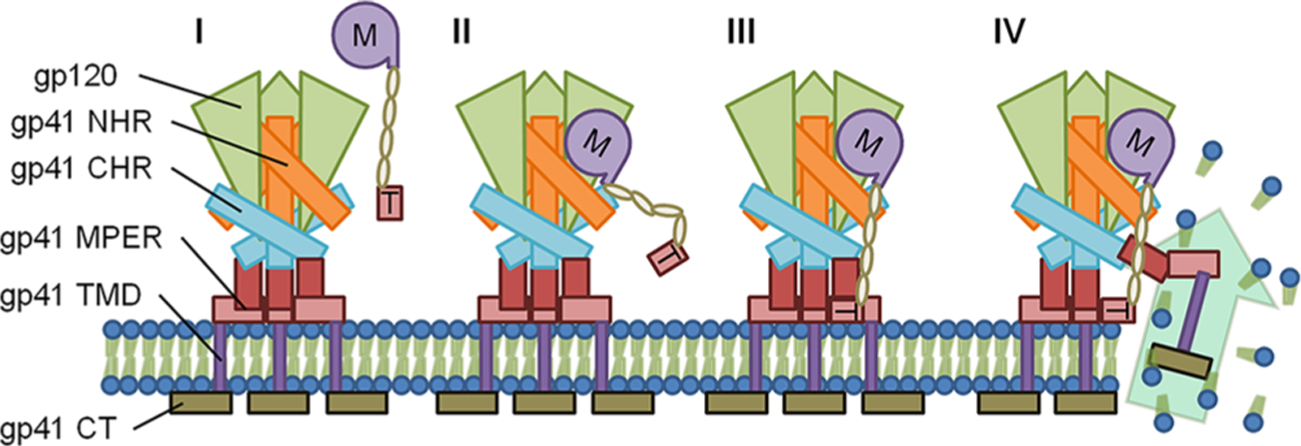

Figure 6.

Schematic of the predicted interaction of M*DAVEI with Env and the membrane. (I) MVN*-L4-Trp3, with MVN* denoted “M” and Trp3 denoted “T”, approaches the surface-exposed Env trimer. (II) The MVN* component binds to gp120 via man-α(1–2)-man terminating glycans, anchoring Trp3 in the vicinity of Env and the membrane via a linker. (III) THe Trp3 component inserts into the membrane and potentially displaces one of the native Env’s MPER and TMD regions. (IV) Displacement of the native MPER/ TMD results in membrane disruption and poration.

An alternative possibility is Trp3 interaction in the NHR region of gp41. Recent studies have identified binding sites for a Trp3-like sequence of T20 in the C-terminal end of the gp41 NHR, resulting in disruption of the NHR’s α-helical structure.40 As M*DAVEI treatment does not cause 6HB rearrangement, binding of Trp3 to the NHR is plausible, though further work would be needed to determine if poration and cytotoxicity would follow from NHR α-helical disruption.

Regardless of the site Trp3 targets in Env, we currently envision that, in dual engagement of Env by MVN*-DAVEI, the role of MVN* would be to securely anchor Trp3 in the vicinity of Env and the membrane, ensuring that Trp3 has the opportunity to interact with gp41 and cause disruption in the membrane. This order of events (i.e., MVN* anchoring followed by Trp3–gp41 interaction) is predicted on the basis of prior data for binding of SPR and ITC to gp120 showing that Trp3 contributes little affinity enhancement and M*DAVEI binding is dominated by the MVN* component [Kd values for MVN* and gp120, 0.021 ± 0.005 μM (SPR) and 0.075 ± 0.011 μM (ITC); Kd values for M*DAVEI and gp120, 0.020 ± 0.006 μM (SPR) and 0.077 ± 0.011 μM (ITC)].22

Cell Membrane Poration by M*DAVEI Occurs without gp120 Being Shed from the gp120–gp41 Complex.

Interestingly, the leakage/poration and cytotoxicity effects induced by M*DAVEI against Env-presenting cells appear to be decoupled from one of the key functional steps of Env rearrangement, gp120 shedding. As described in the Results, Figure 2 and Table 1 show that even as increased concentrations of M*DAVEI were applied to Env-presenting cells, the total “low-Env” detection by mAb 35O22 remains stable, neither increasing nor decreasing significantly. The mAb 35O22 binds to a conformational epitope encompassing the gp120–gp41 interface in prefusion Env and will not bind in the absence of gp120.28,29 The fact that leakage/poration and cytotoxicity proceed in the absence of such transformation suggests that Env–membrane metastability can be accessed by means other than the full native fusion mechanism and that perhaps Env-presenting cells and virus could be inactivated without disturbing immunologically significant epitopes.

When interpreting the data in Figure 2 and Table 1, we cannot rule out the possibility that M*DAVEI could induce an Env conformation not recognized well by mAb 35O22, as suggested by previously observed 35O22 competition of binding of Trp3 to Env.21 However, such a change in antibody recognition does not appear to be the predominant effect of M*DAVEI in this work, as indicated by cell count data. In the assay used, raw cell counts were not dependent on antibody detection. Thus, the population shifts in Figure 2 from the top right quadrant to the bottom left quadrant, as M*DAVEI concentrations increased, cannot be ascribed as being predominantly due to loss of the 35O22 epitope. Although there was some fluctuation of the left-side total cell populations, the lower left cell counts never showed an increase equivalent to the ≥85% of cells lost from the right side. Conceivably, if a significant number of cells were transformed to lose the 35O22 epitope and shift from a theoretical top right quadrant to a post-treatment bottom left quadrant, the cell number for the bottom left would have had to be masked, for example, by nonspecific cytotoxicity. However, no evidence was obtained supporting this possibility, with nonspecific toxicity observed only in some cases at the highest concentrations of M*DAVEI treatment. Thus, the loss of cell counts from the top right quadrants can be concluded to be due mainly to loss of cells rather than to Env transformation.

Off-Target Effects Do Not Account for the Degree of Observed M*DAVEI-Induced Membrane Disruption.

While the cell disruption effects were largely Env-specific, some low-potency, nonspecific effects were also observed. Transfection-dependent loss of cells and cell viability (Figures 3B and 4) was unexpected and presented a concern that excess transfection could harm the cells. The literature on PEI-based transfection reveals well-documented concerns about toxicity and balancing against transfection efficacy, typically becoming apparent within the first 9 h after transfection.41–44 The protocol used in this study did not apply M*DAVEI treatment until 48 h after transfection, so PEI cytotoxicity should already be accounted for by the untreated controls (i.e., addition of 0 μM M*DAVEI).

The control calcein retention and cell viability experiments with nontransfected cells demonstrated a weak nonspecific leakage and killing effect (nontransfected cells in Figure 5). MVN binds to mannose-α(1–2)-mannose terminal glycans, including those on HIV-1 Env, with mutations Q81K and M83R further stabilizing interactions.22–24,45,46 Man-α(1–2)-man-terminating glycans have been quantified on the cell surfaces of nontransfected HEK293 cells (8.4–12.8% of total glycans).47,48 HEK293T cells stably express the SV40 large T antigen but otherwise resemble their parent 293 cell line. This suggests that HEK293T cells present recognizable densities of man-α(1–2)-man glycans on non-HIV surface proteins, allowing M*DAVEI to anchor Trp3 in the vicinity of the cell membrane and potentially cause poration by an off-target effect not involving Env engagement. MVN* acting as a guide and anchor for Trp3’s poration ability is consistent with weak lytic activity observed before by MPER and Trp3 peptides alone against pseudovirus.22

Impact and Future Directions.

We have demonstrated in this study that M*DAVEI causes membrane disruption in Env-presenting cells by means of Env-dependent poration, with sufficient Env expression resulting in cytotoxicity. Furthermore, control experiments show that these poration and cytotoxicity effects are specific to the covalently linked MVN*-L4-Trp3 DAVEI compound and that separate and unlinked mixtures of recombinant protein components are insufficient to cause these effects. These data demonstrate how Env, as a metastable trimer, can be prematurely perturbed to cause membrane disruption, but without triggering key steps in Env’s native fusion program such as gp120 shedding. This vulnerability appears to be inherent to the properties necessary for Env’s fusion and membrane transformation functionality.

The results reported here set the stage for further development of DAVEI constructs for targeting infectious viruses, infected cells, virus-to-cell infection and potentially cell-to-cell infection using Env as the shared target. Further tuning and investigation of gp120 glycan binding beyond the scope of this work could include deglycosylating cells before treatment, either nonspecifically (e.g., PNGase F and Endo H) or specifically (e.g., α−1,2-mannosidase49,50), or by testing against alternate cell lines with differing glycosylation patterns (e.g., H4 human glioma, TZMbl, and CHO-K1). Determining the size of pores formed will also be an important goal. Calcein has an estimated size of ~1.3 nm, which allows it to leak through most pores.30 Bulkier dyes, such as polydextran-linked fluorophores, could provide larger markers for determining the size of individual pores, much as dextran and hemoglobin were used in toxin studies,31,33 and importantly allow estimation of the size of individual membrane disruptions caused by Env perturbation. Experimental determination of DAVEI stoichiometry will be another key future direction for research, utilizing such strategies as heterodisabled Env to determine protomer occupancy in the trimers needed for both infection inhibition and lysis/poration effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Drs. Carole Bewley for providing lectin expertise, Joseph Sodroski, Walther Mothes, and Andres Finzi for key discussions on data and interpretations, and Michael Root and Bibek Parajuli for discussions on trimer interaction statistics.

Funding

This work received funding from National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM115249.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Charles G. Ang, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine and School of Biomedical Engineering, Science, and Health Systems, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102, United States.

Md. Alamgir Hossain, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102, United States.

Marg Rajpara, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102, United States.

Harry Bach, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine and School of Biomedical Engineering, Science, and Health Systems, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102, United States.

Kriti Acharya, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102, United States.

Alexej Dick, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102, United States.

Adel A. Rashad, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102, United States.

Michele Kutzler, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, College of Medicine, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102, United States.

Cameron F. Abrams, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, College of Engineering, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States.

Irwin Chaiken, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Sengupta S, and Siliciano RF (2018) Targeting the Latent Reservoir for HIV-1. Immunity 48, 872–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Hernandez-Vargas EA (2017) Modeling Kick-Kill Strategies toward HIV Cure. Front. Immunol 8 (995), 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Clinical Guidelines: Antiretroviral Therapy In Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach, 2nd ed. (2016) World Health Organization, Geneva. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Gravatt LAH, Leibrand CR, Patel S, and McRae M (2017) New Drugs in the Pipeline for the Treatment of HIV: a Review. Current Infectious Disease Reports 19 (11), 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Xu F, Acosta EP, Liang L, He Y, Yang J, Kerstner-Wood C, Zheng Q, Huang J, and Wang K (2017) Current Status of the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of HIV-1 Entry Inhibitors and HIV Therapy. Curr. Drug Metab 18, 769–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Selhorst P, Grupping K, Tong T, Crooks E, Martin L, Vanham G, Binley J, and Arien K (2013) M48U1 CD4 mimetic has a sustained inhibitory effect on cell-associated HIV-1 by attenuating virion infectivity through gp120 shedding. Retrovirology 10, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Teixeira C, Gomes JR, Gomes P, and Maurel F (2011) Viral surface glycoproteins, gp120 and gp41, as potential drug targets against HIV-1: brief overview one quarter of a century past the approval of zidovudine, the first anti-retroviral drug. Eur. J. Med. Chem 46, 979–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Pacheco B, Alsahafi N, Debbeche O, Prevost J, Ding S, Chapleau JP, Herschhorn A, Madani N, Princiotto A, Melillo B, Gu C, Zeng X, Mao Y, Smith AB 3rd, Sodroski J, and Finzi A (2017) Residues in the gp41 Ectodomain Regulate HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein Conformational Transitions Induced by gp120-Directed Inhibitors. J. Virol 91 (5), e02219–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Acharya P, Lusvarghi S, Bewley CA, and Kwong PD (2015) HIV-1 gp120 as a therapeutic target: navigating a moving labyrinth. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 19, 765–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Finzi A, Pacheco B, Xiang SH, Pancera M, Herschhorn A, Wang L, Zeng X, Desormeaux A, Kwong PD, and Sodroski J (2012) Lineage-specific differences between human and simian immunodeficiency virus regulation of gp120 trimer association and CD4 binding. Journal of virology 86, 8974–8986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kesavardhana S, and Varadarajan R (2014) Stabilizing the native trimer of HIV-1 Env by destabilizing the heterodimeric interface of the gp41 postfusion six-helix bundle. J. Virol 88, 9590–9604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Markovic I, Stantchev TS, Fields KH, Tiffany LJ, Tomic M, Weiss CD, Broder CC, Strebel K, and Clouse KA (2004) Thiol/disulfide exchange is a prerequisite for CXCR4-tropic HIV-1 envelope-mediated T-cell fusion during viral entry. Blood 103, 1586–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Li J, Chen X, Huang J, Jiang S, and Chen YH (2009) Identification of critical antibody-binding sites in the HIV-1 gp41 six-helix bundle core as potential targets for HIV-1 fusion inhibitors. Immunobiology 214, 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Rujas E, Insausti S, Garcia-Porras M, Sanchez-Eugenia R, Tsumoto K, Nieva JL, and Caaveiro JM (2017) Functional Contacts between MPER and the Anti-HIV-1 Broadly Neutralizing Antibody 4E10 Extend into the Core of the Membrane. J. Mol. Biol 429, 1213–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Cerutti N, Loredo-Varela JL, Caillat C, and Weissenhorn W (2017) Antigp41 membrane proximal external region antibodies and the art of using the membrane for neutralization. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 12, 250–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Fu Q, Shaik MM, Cai Y, Ghantous F, Piai A, Peng H, Rits-Volloch S, Liu Z, Harrison SC, Seaman MS, Chen B, and Chou JJ (2018) Structure of the membrane proximal external region of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115, E8892–E8899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Shnaper S, Sackett K, Gallo SA, Blumenthal R, and Shai Y (2004) The C- and the N-terminal regions of glycoprotein 41 ectodomain fuse membranes enriched and not enriched with cholesterol, respectively. J. Biol. Chem 279, 18526–18534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Apellaniz B, Rujas E, Carravilla P, Requejo-Isidro J, Huarte N, Domene C, and Nieva JL (2014) Cholesterol-dependent membrane fusion induced by the gp41 membrane-proximal external region-transmembrane domain connection suggests a mechanism for broad HIV-1 neutralization. J. Virol 88, 13367–13377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Huarte N, Carravilla P, Cruz A, Lorizate M, Nieto-Garai JA, Krausslich HG, Perez-Gil J, Requejo-Isidro J, and Nieva JL (2016) Functional organization of the HIV lipid envelope. Sci. Rep 6, 34190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Contarino M, Bastian AR, Kalyana Sundaram RV, McFadden K, Duffy C, Gangupomu V, Baker M, Abrams C, and Chaiken I (2013) Chimeric Cyanovirin-MPER recombinantly engineered proteins cause cell-free virolysis of HIV-1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 57, 4743–4750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Parajuli B, Acharya K, Yu R, Ngo B, Rashad AA, Abrams CF, and Chaiken IM (2016) Lytic Inactivation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus by Dual Engagement of gp120 and gp41 Domains in the Virus Env Protein Trimer. Biochemistry 55, 6100–6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Parajuli B, Acharya K, Bach HC, Parajuli B, Zhang S, Smith AB 3rd, Abrams CF, and Chaiken I (2018) Restricted HIV-1 Env glycan engagement by lectin-reengineered DAVEI protein chimera is sufficient for lytic inactivation of the virus. Biochem. J 475, 931–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Shahzad-ul-Hussan S, Gustchina E, Ghirlando R, Clore GM, and Bewley CA (2011) Solution structure of the monovalent lectin microvirin in complex with Man(alpha)(1–2)Man provides a basis for anti-HIV activity with low toxicity. J. Biol. Chem 286, 20788–20796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Shahzad-Ul-Hussan S, Sastry M, Lemmin T, Soto C, Loesgen S, Scott DA, Davison JR, Lohith K, O’Connor R, Kwong PD, and Bewley CA (2017) Insights from NMR Spectroscopy into the Conformational Properties of Man-9 and Its Recognition by Two HIV Binding Proteins. ChemBioChem 18, 764–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Montefiori DC (2005) Evaluating neutralizing antibodies against HIV, SIV, and SHIV in luciferase reporter gene assays., In Current Protocols in Immunology (Coligan JE, et al., Eds.) Chapter 12, Unit 12.11, Wiley. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Checkley MA, Luttge BG, and Freed EO (2011) HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein biosynthesis, trafficking, and incorporation. J. Mol. Biol 410, 582–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Holló Z, Homolya L, Davis CW, and Sarkadi B (1994) Calcein accumulation as a fluorometric functional assay of the multidrug transporter. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 1191, 384– 388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Huang J, Kang BH, Pancera M, Lee JH, Tong T, Feng Y, Imamichi H, Georgiev IS, Chuang GY, Druz A, Doria-Rose NA, Laub L, Sliepen K, van Gils MJ, de la Pena AT, Derking R, Klasse PJ, Migueles SA, Bailer RT, Alam M, Pugach P, Haynes BF, Wyatt RT, Sanders RW, Binley JM, Ward AB, Mascola JR, Kwong PD, and Connors M (2014) Broad and potent HIV-1 neutralization by a human antibody that binds the gp41-gp120 interface. Nature 515, 138–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Pancera M, Zhou T, Druz A, Georgiev IS, Soto C, Gorman J, Huang J, Acharya P, Chuang GY, Ofek G, Stewart-Jones GB, Stuckey J, Bailer RT, Joyce MG, Louder MK, Tumba N, Yang Y, Zhang B, Cohen MS, Haynes BF, Mascola JR, Morris L, Munro JB, Blanchard SC, Mothes W, Connors M, and Kwong PD (2014) Structure and immune recognition of trimeric pre-fusion HIV-1 Env. Nature 514, 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Bonnafous P, and Stegmann T (2003) Pore Formation in Target Liposomes by Viral Fusion Proteins In Methods in Enzymology, pp 408–418, Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Ratner AJ, Hippe KR, Aguilar JL, Bender MH, Nelson AL, and Weiser JN (2006) Epithelial cells are sensitive detectors of bacterial pore-forming toxins. J. Biol. Chem 281, 12994–12998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Tran SL, Puhar A, Ngo-Camus M, and Ramarao N (2011) Trypan blue dye enters viable cells incubated with the pore-forming toxin HlyII of Bacillus cereus. PLoS One 6 (9), e22876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Tomita N, Abe K, Kamio Y, and Ohta M (2011) Cluster-forming property correlated with hemolytic activity by staphylococcal gamma-hemolysin transmembrane pores. FEBS Lett. 585, 3452–3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Etxaniz A, Gonzalez-Bullon D, Martin C, and Ostolaza H (2018) Membrane Repair Mechanisms against Permeabilization by Pore-Forming Toxins. Toxins 10 (6), 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Cooper ST, and McNeil PL (2015) Membrane Repair: Mechanisms and Pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev 95, 1205–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Jimenez AJ, and Perez F (2017) Plasma membrane repair: the adaptable cell life-insurance. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 47, 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Bischofberger M, Gonzalez MR, and van der Goot FG (2009) Membrane injury by pore-forming proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 21, 589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Gossert ST, Parajuli B, Chaiken I, and Abrams CF (2018) Roles of conserved tryptophans in trimerization of HIV-1 membrane-proximal external regions: Implications for virucidal design via alchemical free-energy molecular simulations. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet 86, 707–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wang Y, Kaur P, Sun ZJ, Elbahnasawy MA, Hayati Z, Qiao ZS, Bui NN, Chile C, Nasr ML, Wagner G, Wang JH, Song L, Reinherz EL, and Kim M (2019) Topological analysis of the gp41 MPER on lipid bilayers relevant to the metastable HIV-1 envelope prefusion state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 116, 22556–22566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Zhu Y, Ding X, Yu D, Chong H, and He Y (2019) The Tryptophan-Rich Motif of HIV-1 gp41 Can Interact with the N-Terminal Deep Pocket Site: New Insights into the Structure and Function of gp41 and Its Inhibitors. J. Virol 94, e01358–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Godbey WT, Wu KK, and Mikos AG (2001) Poly(ethylenimine)-mediated gene delivery affects endothelial cell function and viability. Biomaterials 22, 471–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lv H, Zhang S, Wang B, Cui S, and Yan J (2006) Toxicity of cationic lipids and cationic polymers in gene delivery. J. Controlled Release 114, 100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Godbey WT, Wu KK, Hirasaki GJ, and Mikos AG (1999) Improved packing of poly(ethylenimine)/DNA complexes increases transfection efficiency. Gene Ther. 6, 1380–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Breunig M, Lungwitz U, Liebl R, and Goepferich A (2007) Breaking up the correlation between efficacy and toxicity for nonviral gene delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 14454–14459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).West MB, Partyka K, Feasley CL, Maupin KA, Goppallawa I, West CM, Haab BB, and Hanigan MH (2014) Detection of distinct glycosylation patterns on human gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 1 using antibody-lectin sandwich array (ALSA) technology. BMC Biotechnol. 14, 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).West MB, Wickham S, Parks EE, Sherry DM, and Hanigan MH (2013) Human GGT2 does not autocleave into a functional enzyme: A cautionary tale for interpretation of microarray data on redox signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signaling 19, 1877–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Costa J, Gatermann M, Nimtz M, Kandzia S, Glatzel M, and Conradt HS (2018) N-Glycosylation of Extracellular Vesicles from HEK-293 and Glioma Cell Lines. Anal. Chem 90, 7871–7879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Hamouda H, Kaup M, Ullah M, Berger M, Sandig V, Tauber R, and Blanchard V (2014) Rapid analysis of cell surface N-glycosylation from living cells using mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res 13, 6144–6151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Kim M-S, and Leahy D (2013) Chapter Nineteen -Enzymatic Deglycosylation of Glycoproteins In Methods in Enzymology (Lorsch J, Ed.) pp 259–263, Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Tremblay LO, and Herscovics A (2000) Characterization of a cDNA encoding a novel human Golgi alpha 1, 2-mannosidase (IC) involved in N-glycan biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem 275, 31655–31660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]