Abstract

Purpose:

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer death in the United States, yet one in three Americans have never been screened for colorectal cancer. Annual screening using fecal immunochemical tests (FIT) is often a preferred modality in populations experiencing CRC screening disparities. While multiple studies evaluate the clinical effectiveness of FITs, few studies assess patient preferences toward kit characteristics. We conducted this community-led study to assess patient preferences for FIT characteristics and to use study findings in concert with clinical effectiveness data to inform regional FIT selection.

Methods:

We collaborated with local health system leaders to select six FITs and recruit age eligible (50–75), English- or Spanish-speaking community members. Participants completed up to six FITs and associated questionnaires and were invited to participate in a follow up focus group. We used a sequential explanatory mixed methods design to assess participant preferences and rank FIT kits. First, we used quantitative data from user testing to measure acceptability, ease of completion, and specimen adequacy through a descriptive analysis of 1) fixed response and open-ended questionnaire items on participant attitudes toward and experiences with FIT kits and 2) a clinical assessment of adherence to directions regarding collection, packaging and return of specimens. Second, we analyzed qualitative data from focus groups to refine FIT rankings, gain deeper insight into the pros and cons associated with each tested kit, and identify CRC screening needs in the community.

Findings:

Seventy-six FITs were completed by 18 participants (Range: 3–6 kits per participant). Over half (56%, n=10) of the participants were Hispanic and 50% were female (n=9). Thirteen participants attended one of three focus groups. Participants preferred FITs that were single sample, used a probe and vial for sample collection, and had simple, large font instructions with colorful pictures. Participants reported difficulty using paper to catch samples, had difficulty labeling tests, and emphasized the importance of having care team members provide instruction no test completion and follow up support for patients with abnormal results. FIT rankings from most to least preferred were: OC-Light®, Hemosure® iFOB Test, InSure® FIT™, QuickVue®, OneStep+, and Hemoccult® ICT.

Conclusions:

FIT characteristics influenced patient’s perceptions of test acceptability and feasibility. Health system leaders, payers, and clinicians should select FITs that are both clinically effective and incorporate patient preferred test characteristics. Consideration of patient preferences may facilitate FIT return, especially in populations at higher risk for experiencing screening disparities.

Keywords: Cancer screening, colorectal cancer, fecal testing, rural, health disparity, patient preferences

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States.1 Screening for CRC aids in early detection and treatment of the disease.2,3 However, in 2015 only 63% of age-eligible adults were up-to-date with CRC screening, and 1 in 3 adults had never been screened.4,5 This is far behind the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable goal to have 80% of age-eligible adults up-to-date by 2018.6 It also falls behind national screening rates for breast and cervical cancer (72% and 81%, respectively).7 Further, disparities in CRC screening persist among rural, minority, and low-income groups.5,8,9

To improve CRC screening rates and to facilitate early detection and treatment, national experts encourage shared decision making and promoting the message, “the best test is the one that gets done.”10,11 The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends multiple screening modalities for average risk adults, including endoscopic (colonoscopy every 10 years; flexible sigmoidoscopy ever 5 years) and annual home-based fecal testing options.12 While colonoscopy is commonly used for CRC testing, many resource-challenged communities find that it is not practical for population-level screening.13,14 Colonoscopy is an expensive test that includes risk of intestinal perforation, requires specially trained medical staff, and has finite capacity, especially in rural areas.15–18 Patients may experience barriers to completing colonoscopies related to emotional (e.g., fear) and logistical challenges (e.g., costs, bowel preparation, transportation, time off work).19–22 Some patients, particularly those in populations experiencing low CRC screening rates, prefer home-based fecal testing to colonoscopy.23–26

Fecal testing is an important component of population-level CRC screening programs,27 the success of which depends highly on participation rates.13,28 Fecal testing detects hidden (occult) or overt blood in the stool, identifies people who are more likely to have early stage CRC, and directs them to colonoscopy.5 More than 130 tests are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the detection of fecal blood on the CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments)-waived database as of June 13, 2017 (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfCLIA/results.cfm). Although guaiac fecal occult blood tests (gFOBT) are cheap and efficacious, they are being replaced by Fecal Immunochemical Tests (FITs) due to superior performance data and higher participation rates.27,29,30 Studies suggest that FITs may have greater adherence because they only require 1 or 2 stool samples and they do not require dietary or medication restrictions.31,32 However, they have not assessed how patients perceive other test characteristics (e.g., collection tool, instruction clarity) nor have they allowed patients to complete and to compare multiple FITs concurrently.

FITs vary in test effectiveness (e.g., sensitivity and specificity)32,33 and other test characteristics (e.g., cost, number of samples, collection tool). While test effectiveness and cost may be primary motivators in FIT selection by clinics and health systems, specific test characteristics may be associated with patient willingness and ability to complete screening as recommended. In 2016, data to inform FIT selection was identified as a priority at Oregon’s CRC Screening Roundtable. Beyond the number of samples required in a fecal test, we found a paucity of research identifying FIT characteristics associated with completion28 and little practical guidance for stakeholders regarding FIT selection. Therefore, we conducted this community-led research study to assess and describe patient preferences for FIT characteristics and to utilize our novel findings from user testing in concert with evidence on test effectiveness to inform selection of a single FIT that could be utilized by primary care and health system leaders in the study region to improve CRC screening rates.

METHODS

This manuscript utilizes data from Finding the Right FIT, a small-scale community-led study conducted from June 1, 2015 to November 30, 2016 with three aims: 1) understand patient preferences for FIT characteristics, 2) assess clinician preferences for CRC screening, and 3) evaluate clinical workflows for fecal testing for CRC. This manuscript reports on findings related to patient preferences, which were assessed using a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design.34,35 First, we used quantitative data from FIT user testing to measure acceptability, ease of completion, and specimen packaging and adequacy. Second, we gathered qualitative data from focus groups to refine FIT rankings and gain deeper insight into the pros and cons associated with each tested FIT kit.

Study design, data collection, and analysis were driven by community-based team members (SC, BF, KC, CY, KD) with the support from academic partners (MD, RP). Our multidisciplinary team had expertise in primary care and community health, health system leadership, popular education and community engagement, and quantitative and qualitative research methodology. This study received approval from the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board (IRB #11893); we received a full waiver of the HIPAA Authorization of written consent. All team members involved in data collection and analysis completed Human Subjects training.

Regional Context and Study Setting

This study was led by community and academic partners associated with the Community Health Advocacy and Research Alliance (CHARA, see www.communityresearchalliance.org) and the Columbia Gorge Health Council (CGHC). The CGHC is governed by a board consisting of healthcare providers, community members, and other stakeholders.36 The CGHC oversees a clinical advisory panel, which consists of primary and behavioral clinicians who provide guidance on clinical standards and implement clinical priorities, and a consumer advisory council. The consumer advisory council includes representatives of the community and each county government served by the Coordinated Care Organization (CCO); Medicaid members must constitute a majority of the council’s membership.37 The CGHC works in partnership with the Columbia Gorge Coordinated CCO, one of 16 accountable care organizations in Oregon that provide coordinated systems of physical and behavioral healthcare for Medicaid recipients in their region.38–40 CCOs were established in 2012 and are accountable to the state through multiple financially-incentivized quality measures, including preventive care, and as of 2013 CRC screening.41,42 CRC screening rates across Medicaid members in Oregon’s CCOs averaged 46.2% and 46.6% in 2014 and 2015 respectively.42

The Columbia Gorge CCO includes two counties in North-Central Oregon, part of the larger 6-county Columbia Gorge region that spans both Oregon and Washington. The region’s 70,000 residents are mostly Caucasian, have lower incomes, and are older than the U.S. average. In addition, some counties have up to 31.1% Latino residents and a significant number of undocumented and uninsured residents.43 The Columbia Gorge CCO’s CRC screening rate was 46.7% in 2014 and 47.3% in 2015.42

Materials: Fecal Immunochemical Tests (FITs)

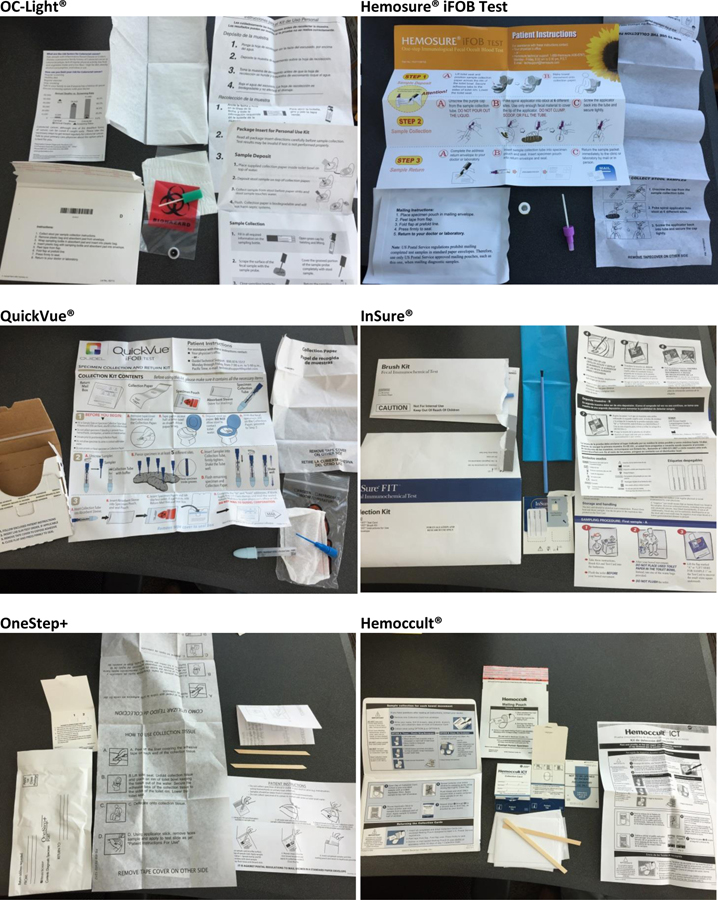

We worked with local primary care clinics and the clinical advisory panel to identify six FIT kits for inclusion, see Table 1. Five FITs (OneStep+, InSure® FIT™, QuickVue®, Hemosure® iFOB Test, Hemoccult® ICT) were used by primary care clinics within the Columbia Gorge CCO. One FIT (OC-Light®) was used widely by other CCOs in Oregon and being considered for use by a clinic in the study region. These FITs varied in terms of collection tools and methods, number of required samples, packaging, instructions, and clinical characteristics (see Table 1). Although laboratory processing of completed FITs was outside the scope of our current study, all 6 FITs were CLIA-waived and could be manually processed at the point of care. We could not locate published data on clinical performance for two of the tests, QuickVue® and OneStep+. Photographs of each FIT kit appear in Appendix 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Fecal Immunochemical Tests (FITs) Identified for User Testing (Selection Date: Summer/Fall 2015)

| FIT kit name (Manufacturer) |

Test Instructions | Materials Included in Kit | # Samples | # Cards | Other Kit Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collection/ Storage Method | Instructions Provided | Other Materials | Positivity Ratea | Sensitivity for CRCb | ||||

| OC-Light® (Polymedco) |

Place paper in toilet, deposit stool onto paper, use grooved probe to collect sample before stool touches water, store sample inside liquid vial. Fill out the label on the tube, wrap tube in absorbent pad, insert into specimen bag. | Grooved probe / Vial | English – Y Spanish – Online only Color Pictures – N |

Specimen bag, biodegradable paper, absorbent pad, CRC fact sheet | 1 | N/A | 8.4–14.2%53,54 | 88–96%53,54 |

| Hemosure® iFOB Test (Hemosure Inc.) |

Affix adhesive paper on toilet, deposit stool on paper, poke grooved probe in stool at 6 different sites, screw applicator back into vial, place into specimen bag. | Grooved probe / Vial | English – Y Spanish – Y Color Pictures – Y |

Specimen bag, adhesive flushable tissue | 1 | N/A | No studies available | 94%55 88%56 (per company website) |

| QuickVue® (Quidel) |

Fill out label on collection vial. Affix paper on toilet and deposit stool on paper. Poke grooved probe in stool at 5 different sites, screw probe into vial, shake. Insert vial into absorbent pad and specimen bag, seal. | Grooved probe / Vial | English – Y Spanish – Y Color Pictures – Y |

Specimen bag, absorbent pad, adhesive flushable tissue | 1 | N/A | No studies available | No studies available |

| InSure® FIT™ (Enterix Inc.) |

Brush stool in toilet water, brush sample on card A. Complete label and affix onto flap to reseal. Repeat process with a different bowel for card B. | Brush (2) / Card | English – Y Spanish – Online only Color Pictures – English only |

N/A | 2 | 1 | 4.6–5.6%57 | 87%57 |

| OneStep+ (Henry Schein) |

Affix paper on toilet, deposit stool on paper, collect sample from 4 different sites of stool using wooden stick. Open flap on sample card, apply sample to window 1, spread evenly to cover, close flap. Repeat to complete window 2 with next bowel. | Wooden Stick (2) / Card | English – Y Spanish – Y Color Pictures – N |

Adhesive flushable tissue | 1–2 | 1 | No studies available | No studies available |

| Hemoccult® ICT (Beckman Coulter) | Place plastic wrap or newspaper over toilet, place provided tissue on top of wrap/newspaper to catch stool over water. Deposit stool, collect two samples with wooden stick, open flap on card, spread samples on flap, close, and dry overnight. Repeat with additional card(s) on a new day. | Wooden Stick (2–3) / Cards | English – Y Spanish – Online only Color Pictures – N |

Flushable tissue | 2 or 3 days | 2–3 | 3.2–9%58,59 | 98%55 |

Positivity rate is the proportion of test that have a positive result.

Sensitivity is the proportion of actual positives which are correctly identified as such (e.g. the percentage of patients with colorectal cancer who are correctly identified as having the condition).

Note: All 6 FIT kits are Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-waived and can be used at the point of care. We could not locate clinical effectiveness data for two of the tests. Many of the 132 tests listed by the Federal Drug Administration for detection of fecal occult blood lack publically available data on clinical effectiveness.

Participants and Recruitment

We engaged local health and social service providers and a bilingual community health worker (BF) to assist with participant recruitment in the CCO region. We distributed English and Spanish recruitment fliers to consumer advisory council and clinical advisory panel members and posted them in public health departments, primary care clinics, and local businesses. We also produced a study public service announcement that was broadcasted on a local Spanish-language radio station.

We sought to enroll up to 30 participants in user testing, with the intent to recruit at least 50% Spanish speaking adults. Eligible participants were (1) residents in the Columbia Gorge region, (2) English or Spanish speaking, (3) uninsured or receiving government insurance coverage, and (4) age eligible for CRC screening (i.e., 50–75). We originally targeted Medicaid patients in the CCO region, but we expanded eligibility to include participants in the broader Columbia Gorge region to increase the final sample size. We conducted an intake call to assess interest and eligibility. Eligible participants were invited to participate in user testing and a focus group. Participants received a $25 gift card for completing up to three FIT kits, a $50 gift card for completing six kits, and an additional $50 gift card for attending a focus group. Participants could elect to have one of the completed FITs returned to their primary care clinic for clinical processing and follow-up. Participants had to return at least one completed questionnaire and a FIT kit to be included in the final analysis.

Data Collection and Analysis

A bilingual community health worker (BF) enrolled participants, distributed FIT kits and questionnaires in a participant’s preferred language (English or Spanish) and instructed them to complete the kits according to manufacturer instructions. Participants were instructed to place all completed kits and questionnaires in a single pre-addressed mailer for return to study staff.

Questionnaires

For each FIT, participants were asked to complete a 20-item questionnaire that assessed ease of completion (e.g., unpacking, mailing), instruction clarity, attitudes toward the process, and time to complete (see example in Appendix 2). Items on the questionnaire were gathered from existing instruments44,45 and revised using partner feedback to facilitate readability (Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level: 4.4). The questionnaire was reviewed by local partners for cultural literacy and translated into Spanish by a certified translator at a regional partner organization. Items employed Likert-style and open-ended response options. For the 13 fixed-response items, we calculated the percentage of participants who endorsed positively worded items (i.e., “Agree” or “Strongly Agree”) and who did not endorse negatively directed items (i.e., (“Disagree” or “Strongly Disagree”). For each item, we then identified the highest and lowest performing kit(s) based on these percentages. Due to the small sample sizes, we provide descriptive statistics only. Open-ended response-options were categorized as “pro” or “con” and tabulated. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0.

Focus Groups

Three focus groups (one English and two Spanish language) were facilitated by community health workers using a semi-structured interview guide (see Appendix 3). Additional project staff attended focus groups to audio record each session, collect detailed field notes, and record FIT prioritization using flip charts. Focus groups lasted 90 minutes on average. The project manager (SC) and the community health worker (BF) used field notes and flip chart lists to prioritized FITs and identify characteristics that facilitated or impeded sample collection. Three team members (RP, MD, KD) conducted an inductive qualitative descriptive analysis to identify patient preferred FIT characteristics.46,47 This included an independent review of field notes followed by group meetings to review codes, reconcile discrepancies, and to identify and finalize emergent themes.

Specimen Adequacy Analysis

Participants could elect to have one completed kit returned to their primary care clinic for laboratory processing. All other returned FITs were included in a specimen adequacy analysis completed by a physician (KD) to assess three main attributes: 1) adequacy of the sample provided, 2) labelling of the specimen kit, and 3) packaging of kit for shipping. FITs that were returned to participant’s primary care clinic for routine clinical care were excluded from the specimen analysis. Criteria for an adequate specimen collection were not included in the manufacturer instructions. Therefore, a descriptive specimen evaluation rubric was developed through an initial examination of kits returned by 5 participants, expert consultation, and input from the study team (Appendix 4); all kits were then evaluated in a single session. Specimens were rated for adequacy using a visual assessment of coloration in vial tests (clear, tan, or brown) or percentage coverage of a card’s test area (more than 50%). Additionally, we assessed if participants attempted to label vials or cards as outlined in the instructions, and if different collection dates were noted for multi-day kits. Finally, we evaluated adherence to manufacturer instructions for repackaging completed kits.

FIT Kit Final Ranking

Two members of the study team (SC, KD) reviewed findings from the questionnaires, specimen evaluation, and focus groups to create a preliminary list of preferred tests and test characteristics. This list was reviewed by the full study team and refined using themes from the focus groups. Differences in FIT rankings were resolved through consensus.

RESULTS

A total of 76 FIT kits and 76 questionnaires were completed by 18 participants (Mean: 4 FITs per participant; Range: 3–6 FITs). As summarized in Table 2, mean participant age was 55 years (Range: 50 – 66 years), 50% (n = 9) were female and 56% (n = 10) self-identified as Hispanic. The majority of participants received government subsidized health insurance including Medicaid, Medicare, or disability (67%); two participants (11%) were uninsured. Thirteen individuals attended one of three focus groups: 10 who completed FIT kits and questionnaires, three who had not (two were 49 years old, one was 78 years old). Seven (54%) focus group participants were Hispanic.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants Engaged in FIT Testing and Focus Groups

| Characteristics | Completed FIT kits and questionnaires (N=18) | Participated in focus group (N=13) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 9 (50) | 8 (62) |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 55.6 (4.3) | 55.5 (7.4) |

| Primary language | ||

| English | 9 (50.0) | 7 (53.8) |

| Spanish | 9 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicaid | 9 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) |

| Medicare | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Uninsured | 3 (16.7) | 5 (38.4) |

| Private | 3 (16.7) | 2 (15.4) |

| Unknown | 1 (5.5) | 0 (0) |

| County of Residence | ||

| Wasco | 10 (55.6) | 9 (69.2) |

| Hood River | 5 (27.8) | 2 (15.4) |

| Multnomah | 2 (11.0) | 1 (7.7) |

| Klickitat | 1 (5.6) | 1 (7.7) |

| FIT or gFOBT in prior 3 years | 5 (29) 1 | 1 (7.7) 2 |

N=17

N=12

Questionnaires

Participant agreement or disagreement with key statements about each FIT kit are summarized in Table 3. Participants reported the most challenges with the Hemoccult® ICT kit, which employs a wooden stick for sample collection and requires multiple samples that are dried between collection days. The OneStep+ kit also employs a wooden stick, but was viewed as easier than completing the Hemoccult® ICT. Participants generally responded positively to the other kits. Participants generally agreed with the statement that collecting the sample was quick (Range: 60%–92%) and reported that they felt confident that they completed the kit correctly (Range: 64%–86%). However, the majority of participants viewed kit completion as disgusting (Range: 18% – 55% disagreed).

Table 3.

Participant Agreement with Statements about the FIT kits on the Study Questionnaires

| OC-Light® n = 12 |

Hemosure® iFOB Test n = 13 |

InSure® FIT™ n = 14 |

QuickVue® n = 12 |

OneStep+ n = 11 |

Hemoccult® ICT n = 11 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Responses Agree/Strongly Agree | ||||||

| After reading the directions, I felt sure I knew how to use the kit correctly. | 83% | 69% | 79% | 75% | 73% | 45% |

| The kit package was easy to open. | 100% | 92% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| The collection tool (tube, brush or stick) was easy for me to use. | 100% | 100% | 93% | 75% | 91% | 64% |

| Collecting the sample was quick. | 92% | 85% | 86% | 83% | 91% | 60% |

| I feel confident I did everything correctly. | 83% | 77% | 86% | 75% | 82% | 64% |

| Most people I know would be willing to complete a kit like this. | 83% | 50% | 67% | 55% | 50% | 27% |

| Using this kit was no big deal. | 84% | 75% | 77% | 58% | 82% | 36% |

| % Responses Disagree/Strongly Disagree | ||||||

| I had problems collecting the stool sample. | 82% | 85% | 79% | 83% | 73% | 60% |

| Collecting the sample was disgusting. | 55% | 46% | 46% | 50% | 18% | 36% |

| [It was] embarrassing to store the sample. | N/A | N/A | 55% | N/A | 50% | 25% |

Overall, participants rated FITs that used probes for sample collection the highest. All respondents reported that the Hemosure® iFOB Test and OC-Light® probes were easy to use and that they had minimal problems with sample collection. Over 90% of participants found the InSure® brush easy to use for sample collection. Although QuickVue® and Hemosure® iFOB has similar characteristics to OC-Light® (i.e., probe, 1 sampling day), participants rated OC-Light® more favorably.

Focus Groups

Four themes emerged from focus groups pertaining to preferences for FIT characteristics and CRC screening. First, in contract to colonoscopy, participants liked that fecal tests could be completed at home, were convenient, generally easy to use, and required no preparation in advance. Second, participants preferred tests that required “one trip to the bathroom” to complete and provided a grooved probe for collecting the sample. In contrast, they disliked collection sticks, multi-sample tests, and cards that required drying samples overnight. However, focus group participants raised questions about how much stool was needed to satisfy a sample, why some kits required six pokes while others only one, and expressed concerns about the effectiveness of using the provided paper to catch the stool sample. Because participants experienced problems with the paper provided to hold the stool out of the toilet water, they recommended using a pie tin or collection hats, such as those provided in hospitals. Additionally, some participants wondered if tests with more cards/samples were better able to detect CRC than single sample tests. Third, participants preferred instructions printed in large font with colorful pictures and were appropriately translated. Specifically, Spanish speakers requested instructions written for Spanish readers instead of relying on automatic translation. Additionally, focus groups participants noted that having a care team member or community health worker review the FIT with them was helpful in understanding how to complete the test and recommended creating instructional videos that could accompany the tests or available on YouTube. Finally, focus groups identified barriers to CRC screening irrespective of modality such as cost, fear, and cultural sensitivities. Participants stressed the importance of providing follow up care and navigation support for colonoscopy scheduling to patients with abnormal FIT results.

Specimen Adequacy Analysis

Table 4 summarizes findings from the specimen evaluation of 66 returned FIT kits (85.7%) in relation to sample adequacy, labeling, and packaging; the remaining 11 FITs were sent to participants’ primary care clinics for processing. Nearly all, 92% (33/36), vial-based kits had an adequate specimen (i.e., liquid in the vial was tan or brown in color) whereas 80% (24/30) of card-based kits had an adequate sample (i.e., specimen covered > 50% of the test area). Many multi-sample cards, especially kits that required two samples on one card, appeared to have been completed with a single sample.

Table 4.

Descriptive Findings from the FIT Kit Specimen Adequacy Analysis (N = 66)

|

OC-Light® (n=12) |

Hemosure® iFOB Test (n=13) |

InSure® FIT™ (n=7) |

QuickVue® (n=11) |

OneStep+ (n=12) |

Hemoccult® ICT (n=11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Packaged correctly | 7/12 (58) | 8/13 (62) | 7/7 (100) | 8/11 (73) | 12/12 (100) | 10/11 (91) |

| In mailer (Y) | 11/12 (92) | 11/13 (85) | 7/7 (100) | 10/11 (91) | 12/12 (100) | 10/11 (91) |

| In bio bag (Y) | 8/12 (67) | 11/13 (85) | N/A | 11/11 (100) | N/A | N/A |

| With pad (C) | 7/12 (58) | 8/13 (62) | N/A | 9/11 (82) | N/A | N/A |

| Labeled correctly | 8/12 (67) | 5/13 (38) | 6/7 (86) | 5/11 (45) | 8/12 (67) | 7/11 (64) |

| Label (Y) | 7/12 (58) | 5/13 (38) | 5/7 (71) | 5/11 (45) | 7/12 (58) | 7/11 (64) |

| Different days (Y) | N/A | N/A | 4/7 (57) | N/A | 4/12 (33) | 5/11 (45) |

| Collection date (Y) | 8/12 (67) | 5/13 (38) | 6/7 (86) | 4/11 (36) | 7/12 (58) | 7/11 (64) |

| Sampled correctly | 10/12 (83) | 12/13 (92) | 6/7 (86) | 11/11 (100) | 11/12 (92) | 7/11 (64) |

| Color of liquid (T/B) | 10/12 (83) | 12/13 (92) | N/A | 11/11 (100) | N/A | N/A |

| Returned all cards | N/A | N/A | 7/7 (100)* | N/A | 12/12 (100) | 9/11 (82)** |

| Sample on all cards | N/A | N/A | 7/7 (100) | N/A | 11/12 (92) | 8/11 (73)** |

| Specimen appearance (N/S/So) | N/A | N/A | 7/7 (100) | N/A | 12/12 (100) | 10/11 (91) |

| Coverage (>50%) | N/A | N/A | 6/7 (86) | N/A | 11/12 (92) | 7/11 (64) |

| Closed | N/A | N/A | 7/7 (100) | N/A | 12/12 (100) | 10/11 (91) |

Y = Yes; C = Correct; T=Tan; B= Brown; N=None; S=stain; So=Solid

1 card total,

3 cards total

When participants attempted to write on vials that had pre-attached labels, their handwriting was often illegible. However, only 38% (5/13) of Hemosure® iFOB Test kits were labeled compared to 86% (6/7) of InSure® FIT™ kits. Kit packaging also varied widely. Overall, 64% (23/36) of vial-based tests were packaged correctly. Specifically, 83% (30/36) of the vial-based tests were properly returned in the biohazard bag, but only 55% (24/36) were wrapped in the absorbent pad. Packaging errors on vial tests included placing the vial directly in the mailer without enclosing in the biohazard bag and returning the vial without the absorbent pad included. Comparatively, 97% (29/30) of card based tests were packed according to manufacturer instructions with secured card flaps over the sample site with stickers. However, two of the mailing envelopes included waste materials from the kit, making them too heavy for mailing with the recommended postage.

Final FIT Ranking

As summarized in Table 5, the top two tests (OC-Light® and Hemosure® iFOB Test) utilized a probe and required a single sample. The third FIT (InSure® FIT™) required a brush and two days of sampling, yet ranked highly on all assessments in part due to a colorful and clear instruction sheet.

Table 5.

FIT Kit Rankings from Most to Least Preferred by Questionnaire and Focus Group Data.

| A. Combined Rankings for FIT kit User Testing Data Sets. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Source |

||||

| FIT Name | Questionnaire (n =79) |

English Focus Group (n=6) |

Spanish Focus Group (n=8) |

Overall |

| OC-Light® | 1 | 1 | 2/3* | 1 |

| Hemosure® iFOB Test | 2/3* | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| InSure® FIT™ | 2/3* | 2 | 2/3* | 3 |

| QuickVue® | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| OneStep+ | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Hemoccult® ICT | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| B. Test Characteristics for Overall FIT Kit Ranking. | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collection Tool | Instructions | # Sampling Days | # Cards | ||||||||

| Kit Ranking | Probe | Stick | Brush | Colored Pictures | Large Font | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1. OC-Light® | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 2. Hemosure® iFOB Test | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 3. InSure® FIT™ | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 4. QuickVue® | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 5. OneStep+ | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 6. Hemoccult® ICT | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

2/3 signify a tie for second place.

DISCUSSION

Participants in our study clearly preferred FITs that utilize a probe and vial for collection, had simple instructions that include large font text and colorful pictures, and require only one sample. Participants had difficulty providing accurate and legible labeling on samples, and multi-specimen tests often appeared to have been completed with a single sample. Final FIT rankings from most to least preferred were: OC-Light®, Hemosure® iFOB Test, InSure® FIT™, QuickVue®, OneStep+, and Hemoccult® ICT. Additionally, participants provided suggestions for kit improvement, described the benefit of having care team members provide instruction for FIT completion, and stressed the importance of providing follow-up care and navigation support for patients with abnormal results. Attending to patient preferred FIT characteristics may facilitate patient return, clinical processing, and thus improve CRC screening rates and ultimately reduce cancer morbidity and mortality.

Current guidelines and national recommendations emphasize helping patients use the CRC screening modality that best suits their preferences. 10,11 Our study evaluated FITs, which prior to fall 2016 were one of three screening modalities recommended by the USPSTF.12,48 In the United States and internationally, FITs are replacing older gFOBT options as the standard of care for home-based fecal testing for CRC due to superior performance data and higher participation rates.27,29,30 Currently, 132 different FOBT/FITs are cleared for use in the United States by the FDA for the “detection of blood” in the stool. We assessed 6 FITs that were actively being used by primary care clinics within one region. However, two of the selected FITs did not include published data on clinical effectiveness. A 2013 study by Daly and colleagues found that many FOBT/FIT products listed on the FDA website lacked publically available proficiency testing information to help healthcare professionals make informed decisions regarding test selection.32 An important consideration for future research is how to generate publically available data on FIT effectiveness, and how best to support the adoption and use of FITs that are clinically effective and preferred by patients in practice.

Test effectiveness is a critical factor to consider when selecting a FIT kit. However, other physical test characteristics may determine whether patients complete these tests and if they do so correctly. Understanding how patients view the characteristics of FITs currently available on the market can inform product refinement and may facilitate completion. Previous research identified preferences for certain FITs, such as those that only require a single sample.31,49 Other studies have assessed patient perceptions of FIT/FOBTs and reason for completion.44,49–51 For example Gordon and colleagues identified nonusers discomfort in completing the kit and uses suggestions to add disposable gloves, extra paper, and wider-mouth collection vials.50 However, no studies that we are aware of allow patients complete multiple FITs such that they can compare and contrast between them. Our study addresses key gaps in the research by identifying multiple characteristics that patients perceive make specific FITs easier to complete. Although initially our study set out to recommend a single FIT kit, we found that patients preferred test characteristics shared by more than one kit.

There are a few notable limitations in the present study. First, we tested six FITs that were actively used in the region and varied in their clinical effectiveness, two of which did not have publically available data on clinical effectiveness. Health system leaders should consider both clinical and physical test characteristics when selecting a FIT for local or regional use. Additionally, there may be other FIT characteristics that merit evaluation. Second, we had difficulty recruiting users in our original target population. In response, we expanded our geographic range, included individuals beyond those covered by Medicaid, extended the recruitment timeframe, and implemented protocols to allow participants to return one test to their primary care practice for laboratory testing. Attending to these factors as well as asking patients to complete fewer FITs may facilitate recruitment in future studies. Third, our study was a small-scale community-based study primarily designed to inform FIT selection in one rural region. Although 76 FITs were completed, they were returned by 18 participants who all identified as either Caucasian or Hispanic/Latino. Future studies with a larger, more diverse participant sample could evaluate how FIT preferences differ by participant characteristics (e.g., low versus higher socioeconomic status) and may reveal different preferences across racial/ethnic subgroups and regions. Lastly, although we allowed participants to send one kit for laboratory analysis, our assessment of sample adequacy used a qualitative rubric designed through expert consultation. Given that we assessed color and/or card coverage and instructed participants not to label tests with their names, actual laboratory processing may have resulted in different outcomes for sample completion.

Despite these limitations, we observed variation in participants’ ability to complete and their perceptions of different FITs. Our findings add to the body of knowledge on patient perceptions of FIT acceptability and feasibility of use. Results – when used in concern with data on clinical effectiveness - can inform primary care clinicians, health system leaders, and payers who seek to increase CRC screening through home-based fecal testing. Additionally, findings provide important feedback for manufacturers who can improve kit characteristics (e.g., collection method) and to refine the associated instructions to address patient concerns with completing the test (i.e., what if sample gets wet). Although some systems and research teams have created pictographs or wordless instructions for low-literacy adults,52 changes by the manufacturer could support wide-spread distribution and uptake in low as well as high resourced settings. Finally, our results can advise the design of future studies that assess additional FIT kits in larger samples that extend beyond rural English- and Spanish-speakers and single geographic regions. These studies can offer more sophisticated analyses measuring adequacy of returned FITs and tease apart the association between FIT kit characteristics (e.g., number of samples, collection method, instructions) on patient adherence in clinical practice.

CONCLUSION

Test characteristics influenced patient’s perceptions of FIT acceptability and feasibility of use. Study participants preferred FITs that require only one sample, use a probe and vial to collect the sample, and have descriptive instructions with large font and colored pictures. Participants reported difficulty using paper to catch samples, had difficulty labeling tests, and emphasized the importance of having care team members provide instruction on test completion and offering follow up support for patients with an abnormal result. Findings can be used by manufacturers to improve test characteristics and by researchers to inform larger-scale studies and intervention trials. When considered in concert with information on FIT effectiveness, clinics and health systems can use our results to inform test selection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank our study participants and the various community partners who supported study recruitment. The Columbia Gorge Health Council served as the fiscal agent, provided time for staff participation, and supported engagement of the Columbia Gorge Coordinated Care Organization’s Community Advisory Council (CAC) and Clinical Advisory Panel (CAP). The Community Health Advocacy and Research Alliance (CHARA) provided training and infrastructure that enabled the current study. Gloria Coronado, PhD helped team members identify and procure Fecal Immunochemical Tests (FITs). Staff from Nuestra Comunidad Sana at The Next Door Inc. created community flyers and translated Spanish surveys. FITs used in this study were donated by the manufactures: Beckman Coulter, Polymedco, Henry Schein, Hemosure, Enterix and Quidel. We appreciate the assistance of Eliana Sullivan with manuscript revisions.

FUNDING

This study was funded in part through a research grant from the Oregon Health and Science University Knight Cancer Institute Community Partnership Program (ID # CPP.2014.07). Dr. Davis is partially supported by an Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality patient centered outcomes research (PCOR) K12 award (Award # K12 HS022981 01). The Community Health Advocacy and Research Alliance (CHARA) was developed through a series of Pipeline to Proposal Awards from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (ID #7735932, 7735932-A, 7735932B). The findings and conclusions in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funders.

Appendix 1. Images and Materials Associated with each FIT kit Tested (N = 6).

Appendix 2. Sample FIT Questionnaire, Administered with each FIT Kit

| FIT Kit Feedback Form | ID number: |

| Please complete one form for each FIT kit as soon as you are done with that kit. | |

| Return this completed form and completed FIT kit by mail using the envelope provided within 2 weeks. | |

Participant # ______

Brand name of KIT you are rating:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The kit package was easy to open. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. The directions were confusing. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. After reading the directions, I felt sure I knew how to use the kit correctly. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4. I had problems collecting the stool sample. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 5. The collection tool (tube, brush or stick) was easy for me to use. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 6. Collecting the sample was quick. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 7. Collecting the sample was disgusting. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 8. I feel confident I did everything correctly. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I know how to return the kit. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. I have a convenient place to mail the kit. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. Most people I know would be willing to complete a kit like this. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 4. Using this kit was no big deal. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

13. How many different bowel movements were required to complete this kit? 1 2 3

If more than 1 bowel movement was required, please answer the following:

| Strongly Disagree |

Disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13a. It was embarrassing to store the stool card between samples. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 13b. I would rather do a one-sample test, even if a multi-day test is a little better at finding symptoms of cancer. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| 13c. I would rather do a one-sample test, even if a multi-day test is a lot better at finding symptoms of cancer. | □ | □ | □ | □ |

14. How many days did it take you to do all of the steps for this FIT kit, from receiving the package to getting the completed kit ready to mail? Circle your answer.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15+

15. Overall, what did you think about completing this FIT kit? If you have completed the other kits as part of this study, is this kit better or worse?

16. What problems, if any, did you have using this kit?

17. Please share any additional comments or thoughts here.

Appendix 3. FIT Kit Evaluation Rubric Used in Specimen Adequacy Analysis

Participant #:

Test Kit #:

| 1) “Packaged correctly” (if applicable): | Y* / N |

| a) For all tests - Was the specimen returned inside the mailer (without regard to whether it was sealed or left unsealed)? | Y / N |

| b) For vial tests - Was the specimen inside the biohazard bag/inner envelope (without regard to whether it was sealed)? | Y / N |

| c) For vial tests - Was the absorbent pad in the bag/envelope? | Yes Correctly/Yes, but incorrectly/No |

| 2) ”Labeled correctly” | Y* / N |

| a) Was the specimen labeled in any way? | Y / N |

| b) For card-based tests – Are the stool specimens dated on different days? | Y / N |

| c) For all tests – Is the collection date listed? | Y / N |

| 3) “Sampled correctly” | Y* / N |

| For vial tests | |

| a) Liquid appearance | Clear/Tan/Brown |

| For card-based tests | |

| b) Number of cards returned | 1 / 2 / 3 |

| b) Do the specimens appear different from each other in color or texture? | Y / N |

| c) Specimen appearance | None / Staining / Solid |

| d) Percentage of test area with visible staining or solid stool | 0 / 1–50% / 51–80% / 80–100% |

| e) Were the specimen cards closed according to instructions (without regard to whether the adhesive seal was used)? | Y / N |

Where Y = yes to all

Appendix 4. Semi-structured Interview Guide for Focus Groups

Materials to bring:

Study Information sheet

Gift cards of appreciation

Food

Information handouts from American Cancer Society (ACS) in English and Spanish

FIT kits

Recorder

Flip chart and markers

Prior to Starting Focus Group

Hand out study information sheet and review with participants

Welcome Group

Introductions

Thanks for coming

- Purpose of today’s meeting

- Help us better understand opinions on the FIT kits that are used in the community and understand the best ways to educate about colorectal cancer prevention

- Gather valuable opinions from the group about the FIT kits

- How to educate the community on colorectal cancer screening

- Ground rules to encourage participation and ensure everyone feels safe sharing their thoughts

- As the information sheet indicated, the information you provide will be kept private and so will the identity of every person participating in this study.

- It’s best if only one person speaks at a time. It is important that we all listen and try to understand what each other is saying.

- If someone says something and I say “do you all agree with that statement?” No comment assumes you agree.

- As you answer questions, I may ask you follow-up questions to help make sure I understand your responses.

- There are no “right” or “wrong” answers.

- It is important for you to know that you do not have to answer any questions if you do not want to.

Any questions?

Announce you are turning on recorder [turn on audio recorder].

[Note: These questions provide a semi-structured guide for the discussion. Follow-up questions may be necessary for further clarification.]

Questions for the group:

-

1

I know we know many of you, but can we quickly go around the room and have you state your name.

FIT test questions: Let’s talk about the FIT kits (group facilitator to take out all the FIT kits and have them in front of the group)

-

2

Brainstorm overall impressions of the process of FIT testing and the kits

-

3

Discuss each FIT kit and if it was one that you tried, please let us know what you liked about the kit and what was challenging for you. Think about the tools given in the kit, the process, and directions.

-

4

Review Positives and Drawbacks for kits (materials, process, and directions).

-

5

Ask participants to agree on a ranking for all 6 kits from most preferred to least preferred.

-

6

Ask participants to make recommendations to the medical community about the FIT kits and FIT testing in general.

CRC Screening Questions:

-

7

Ask about CRC Screening (general brainstorm – what comes to mind?)

-

8

Ask: What makes it harder to complete screening? What are the barriers to screening?

-

9

Ask: What are some positives about testing? Can the group come up with ideas or ways to make screening a more positive experience?

Sharing Information about CRC screening:

-

10

Ask: Where do people get health information/CRC screening information from?

-

11

Ask: Who would they like to receive their health information from?

-

12

Ask: How do we increase education and awareness about colorectal cancer and screening in the community?

If time allows: ask for feedback on what went well and what could be improved on with this focus group.

Thank the group for coming and hand out resource materials. Read below:

We want to thank each and every one of you for participating in this project. We have realized that this effort was only one small piece in a long path toward improving linkages between primary care and community-based resources for colorectal cancer screening and awareness. Work in this area will continue to grow and your opinions and time are so valuable to us. We’ve learned a lot from this process and we greatly appreciate your time and energy in working on such an important area of research.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None stated.

NOTE TO NIH: PLEASE INCLUDE:

The published version of this article can be accessed on the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine website at: http://jabfm.org/content/30/5/632.full

Contributor Information

Robyn Pham, Tiny Hands International.

Suzanne Cross, Columbia Gorge Health Council.

Bianca Fernandez, The Next Door Inc..

Kathryn Corson, Research Consultant.

Kristen Dillon, PacificSource Columbia Gorge CCO.

Coco Yackley, Columbia Gorge Health Council.

Melinda M Davis, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon 97239.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2014–2016. Atlanta: American Cancer Society;2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zauber AG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, Wilschut J, van Ballegooijen M, Kuntz KM. Evaluating test strategies for colorectal cancer screening: a decision analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):659–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, Beil TL, Fu R. Screening for colorectal cancer: A targeted, updated systematic review for the u.s. preventive services task force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;149(9):638–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morbidity, and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Vital Signs: Colorectal Cancer Screening Test Use - United States, 2012. MMWR. 2013;62(44):881–888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Society AC. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2017–2019. Atlanta: American Cancer Society;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.80% by 2018. 2016; http://nccrt.org/tools/80-percent-by-2018/. Accessed January 23, 2017.

- 7.Sabatino SA, White MC, Thompson TD, Klabunde CN, Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Cancer screening test use - United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(17):464–468. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole AM, Jackson JE, Doescher M. Urban-rural disparities in colorectal cancer screening: cross-sectional analysis of 1998–2005 data from the Centers for Disease Control’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Study. Cancer medicine. 2012;1(3):350–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis MMRS, Pham R, et al. Geographic and Popluation-Level Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Multilevel Analysis if Medicaid and Commercial Claims Data. Preventive medicine. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Gupta S, Sussman DA, Doubeni CA, et al. Challenges and possible solutions to colorectal cancer screening for the underserved. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(4):dju032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieberman D, Ladabaum U, Cruz-Correa M, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer and evolving issues for physicians and patients: A review. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2135–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United, States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Final Update Summary: Colorectal Cancer: Screening. 2016.

- 13.Honein-AbouHaidar GN, Kastner M, Vuong V, et al. Benefits and barriers to participation in colorectal cancer screening: a protocol for a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackie A Moving from guaiac faecal occult blood test (gFOBT) to a faecal immunochemical test for haemoglobin (FIT) in the bowel screening programme: A consultation. 2015.

- 15.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer and Adenomatous Polyps, 2008: A Joint Guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology*†. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2008;58(3):130–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levin TR, Zhao W, Conell C, et al. Complications of Colonoscopy in an Integrated Health Care Delivery System. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145(12):880–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman RM, Espey D, Rhyne RL. A public-health perspective on screening colonoscopy. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 2011;11(4):561–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panteris V, Haringsma J, Kuipers EJ. Colonoscopy perforation rate, mechanisms and outcome: from diagnostic to therapeutic colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41(11):941–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoenberg NE, Eddens K, Jonas A, et al. Colorectal cancer prevention: Perspectives of key players from social networks in a low-income rural US region. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2016;11(1):30396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowyer HL, Vart G, Kralj-Hans I, et al. Patient attitudes towards faecal immunochemical testing for haemoglobin as an alternative to colonoscopic surveillance of groups at increased risk of colorectal cancer. Journal of medical screening. 2013;20(3):149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruffin MTt, Creswell JW, Jimbo M, Fetters MD. Factors influencing choices for colorectal cancer screening among previously unscreened African and Caucasian Americans: findings from a triangulation mixed methods investigation. J Community Health. 2009;34(2):79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green BB, Coronado GD, Devoe JE, Allison J. Navigating the murky waters of colorectal cancer screening and health reform. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):982–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inadomi JM, Md, Vijan S, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: A randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172(7):575–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shokar NK, Carlson CA, Weller SC. Informed Decision Making Changes Test Preferences for Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Diverse Population. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2010;8(2):141–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeBourcy A, Lichtenberger S, Felton S, Butterfield K, Ahnen D, Denberg T. Community-based Preferences for Stool Cards versus Colonoscopy in Colorectal Cancer Screening. J GEN INTERN MED. 2008;23(2):169–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta S, Halm EA, Rockey DC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of fecal immunochemical test outreach, colonoscopy outreach, and usual care for boosting colorectal cancer screening among the underserved: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2013;173(18):1725–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allison JE, Fraser CG, Halloran SP, Young GP. Population screening for colorectal cancer means getting FIT: the past, present, and future of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal immunochemical test for hemoglobin (FIT). Gut and liver. 2014;8(2):117–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vart G, Banzi R, Minozzi S. Comparing participation rates between immunochemical and guaiac faecal occult blood tests: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Preventive medicine. 2012;55(2):87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tinmouth J, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Allison JE. Faecal immunochemical tests versus guaiac faecal occult blood tests: what clinicians and colorectal cancer screening programme organisers need to know. Gut. 2015;64(8):1327–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Endoscopy Organization. FIT for Screening. 2017; http://www.worldendo.org/about-us/committees/colorectal-cancer-screening/ccs-testpage2-level4/fit-for-screening/. Accessed Jan 31, 2017

- 31.Chubak J, Bogart A, Fuller S, Laing SS, Green BB. Uptake and positive predictive value of fecal occult blood tests: A randomized controlled trial. Preventive medicine. 2013;57(5):671–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daly JM, Bay CP, Levy BT. Evaluation of Fecal Immunochemical Tests for Colorectal Cancer Screening. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health. 2013;4(4):245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, Levin TR, Corley DA. Accuracy of Fecal Immunochemical Tests for Colorectal Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2014;160(3):171–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark VL, Smith KC. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences. Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR);2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nay B, Knivila K. Oregon’s Coordinated Care Organizations—Health System Transformation or Managed Care Revisited? Insights. Vol Winter 2013: Williamette Management Associates; 2013.

- 37.OregonLaws.org. 2015 ORS 414.627 Community Advisory Councils. 2015.

- 38.McConnell K Oregon’s medicaid coordinated care organizations. JAMA. 2016;315(9):869–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McConnell KJ. Oregon’s Medicaid Coordinated Care Organizations. Jama. 2016;315(9):869–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McConnell KJ, Renfro S, Chan BK, et al. Early Performance in Medicaid Accountable Care Organizations: A Comparison of Oregon and Colorado. JAMA internal medicine. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Oregon Health Authority. CCO Metrics. 2013.

- 42.Oregon Health Authority. Oregon’s Health System Transformation: CCO Metrics 2015 Final Report. 2016.

- 43.Columbia Gorge Regional Community Health Assessment [PDF]. December 2013.

- 44.Worthley DL, Cole SR, Mehaffey S, et al. Participant satisfaction with fecal occult blood test screening for colorectal cancer. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2007;22(1):142–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deutekom M, van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, et al. Comparison of guaiac and immunological fecal occult blood tests in colorectal cancer screening: the patient perspective. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2010;45(11):1345–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Andersen RS, Sondergaard J. Qualitative description – the poor cousin of health research? BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2009;9(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandelowski M Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.File Update Summary: Colorectal Cancer: Screening. July 2015; https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening.

- 49.Cole SR, Young GP, Esterman A, Cadd B, Morcom J. A randomised trial of the impact of new faecal haemoglobin test technologies on population participation in screening for colorectal cancer. Journal of medical screening. 2003;10(3):117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gordon NP, Green BB. Factors associated with use and non-use of the Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) kit for Colorectal Cancer Screening in Response to a 2012 outreach screening program: a survey study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Sullivan I, Orbell S. Self-sampling in screening to reduce mortality from colorectal cancer: a qualitative exploration of the decision to complete a faecal occult blood test (FOBT). Journal of medical screening. 2004;11(1):16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coronado GD, Sanchez J, Petrik A, Kapka T, DeVoe J, Green B. Advantages of wordless instructions on how to complete a fecal immunochemical test: lessons from patient advisory council members of a federally qualified health center. Journal of cancer education : the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education. 2014;29(1):86–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chiang TH, Lee YC, Tu CH, Chiu HM, Wu MS. Performance of the immunochemical fecal occult blood test in predicting lesions in the lower gastrointestinal tract. CMAJ. 2011;183(13):1474–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheng TI, Wong JM, Hong CF, et al. Colorectal cancer screening in asymptomaic adults: comparison of colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and fecal occult blood tests. J Formos Med Assoc. 2002;101(10):685–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daly JM, Bay CP, Levy BT. Evaluation of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer screening. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4(4):245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benefits. The New Recommended Technology for Occult Blood Detection to Aid in Colorectal Cancer Screening [Website]. http://hemosure.com/sales/benefits/. Accessed March 23, 2017, 2017.

- 57.Smith A, Young GP, Cole SR, Bampton P. Comparison of a brush-sampling fecal immunochemical test for hemoglobin with a sensitive guaiac-based fecal occult blood test in detection of colorectal neoplasia. Cancer. 2006;107(9):2152–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allison JE, Sakoda LC, Levin TR, et al. Screening for colorectal neoplasms with new fecal occult blood tests: update on performance characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(19):1462–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ko CW, Dominitz JA, Nguyen TD. Fecal occult blood testing in a general medical clinic: comparison between guaiac-based and immunochemical-based tests. Am J Med. 2003;115(2):111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]