Abstract

The emergence of artemisinin resistance, combined with certain sub-optimal properties of ozonide agents arterolane and artefenomel has necessitated the search for new drug candidates in the endoperoxide class. Our group has focused on trioxolane analogs with substitution patterns not previously explored. Here we describe the enantioselective synthesis of analogs bearing a trans-3” carbamate side chain and find these to be superior, both in vitro and in vivo, to the previously reported amides. We identified multiple analogs that surpass the oral efficacy of arterolane in the P. berghei model while exhibiting drug-like properties (logD, solubility, metabolic stability) similar or superior to next-generation clinical candidates like E209 and OZ609. While the preclinical assessment of new analogs is still underway, current data suggest the potential of this chemotype as a likely source of future drug candidates from the endoperoxide class.

Keywords: Antimalarials, endoperoxides, trioxolanes, lead optimization, stereoselective synthesis

Graphical Abstract

Despite significant recent progress in the prevention and treatment of malaria, infection by Plasmodium spp. parasites remains a cause of significant morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia.1 Emerging artemisinin resistance resulting from mutations in the PfKelch13 (K13)2–3 protein has spurred the search for new compounds that might replace current artemisinin analogs as the rapidly killing component in future antimalarial combination therapies. The 1,2,4-trioxolane artefenomel (OZ439)4 remains a strong candidate to play this role due to a prolonged exposure profile in human patients that when modelled in ring-stage survival assays5–7 predicts for clinical efficacy against K13-mutant parasites. However, the 800 mg dose of artefenomel studied clinically has proven extremely challenging to formulate due to its poor aqueous solubility and lipophilic nature.8 Thus, despite promising pharmacodynamic (PD) properties, it remains unclear whether artefenomel will ultimately prove a suitable replacement for artemisinin in antimalarial combinations. Nor does a tetraoxane development candidate (E209),10 which bears an artefenomel-like structure and even higher reported LogD7.4 value, seem likely to overcome these challenges. A recent resurgence of efforts aimed at identifying compounds with superior drug-like properties, notably enhanced solubility and stability to metabolism, has seen the nomination of OZ6096 (Figure 1) as the leading drug candidate from this class.

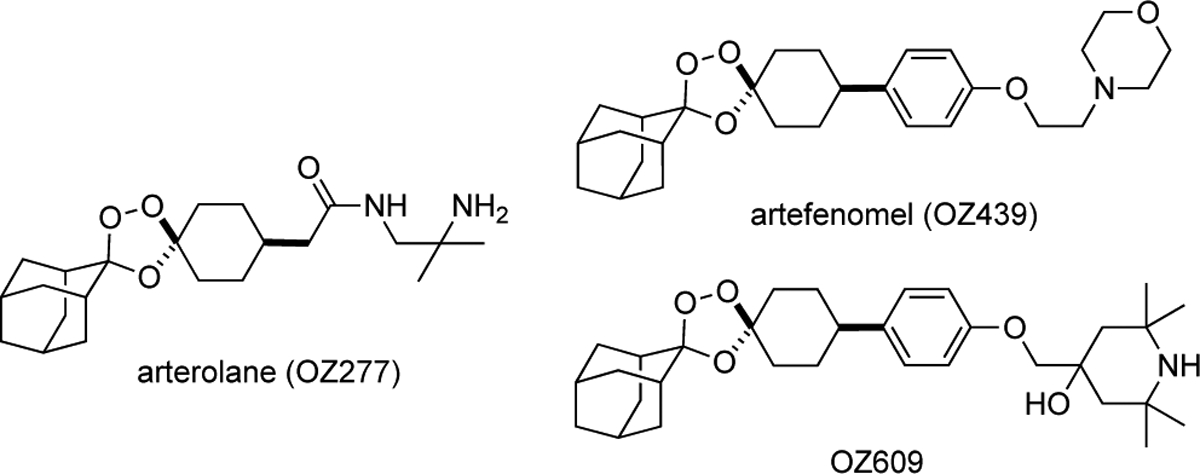

Figure 1.

Structure of arterolane11 and newer trioxolane drug candidates artefenomel4 and OZ6096.

Arterolane11 in fact exhibits excellent solubility and reduced lipophilicity as compared to the more recent drug candidates. However, a shorter half-life of the drug in infected patients predicts for inferior clinical efficacy, including against K13-mutant parasites where the more durable killing effect conferred by OZ439 and OZ609 is most desirable.7 It is worth noting that the distinct pharmacological properties of the various ‘OZ’ agents derive entirely from differences in the side chain emerging from the cyclohexane ring (Figure 1). Indeed, Vennerstrom and Charman first proposed12 that the ferrous iron reactivity, and thus antiparasitic activity, of OZ compounds is governed by the conformational preferences of the cyclohexane ring, which are in turn determined by the nature of the pendant side chain. Following this reasoning, we considered that control over conformation might be equally well achieved with trans-R3 substitution (Figures 2 and 3). To test this notion, we devised a stereocontrolled synthesis of arterolane-like analogs bearing trans-R3 side chains13 and gratifyingly found that these compounds exhibited potencies and in vivo efficacy on par with or even superior to canonical OZ-like cis-R4 analogs (Figure 2).13

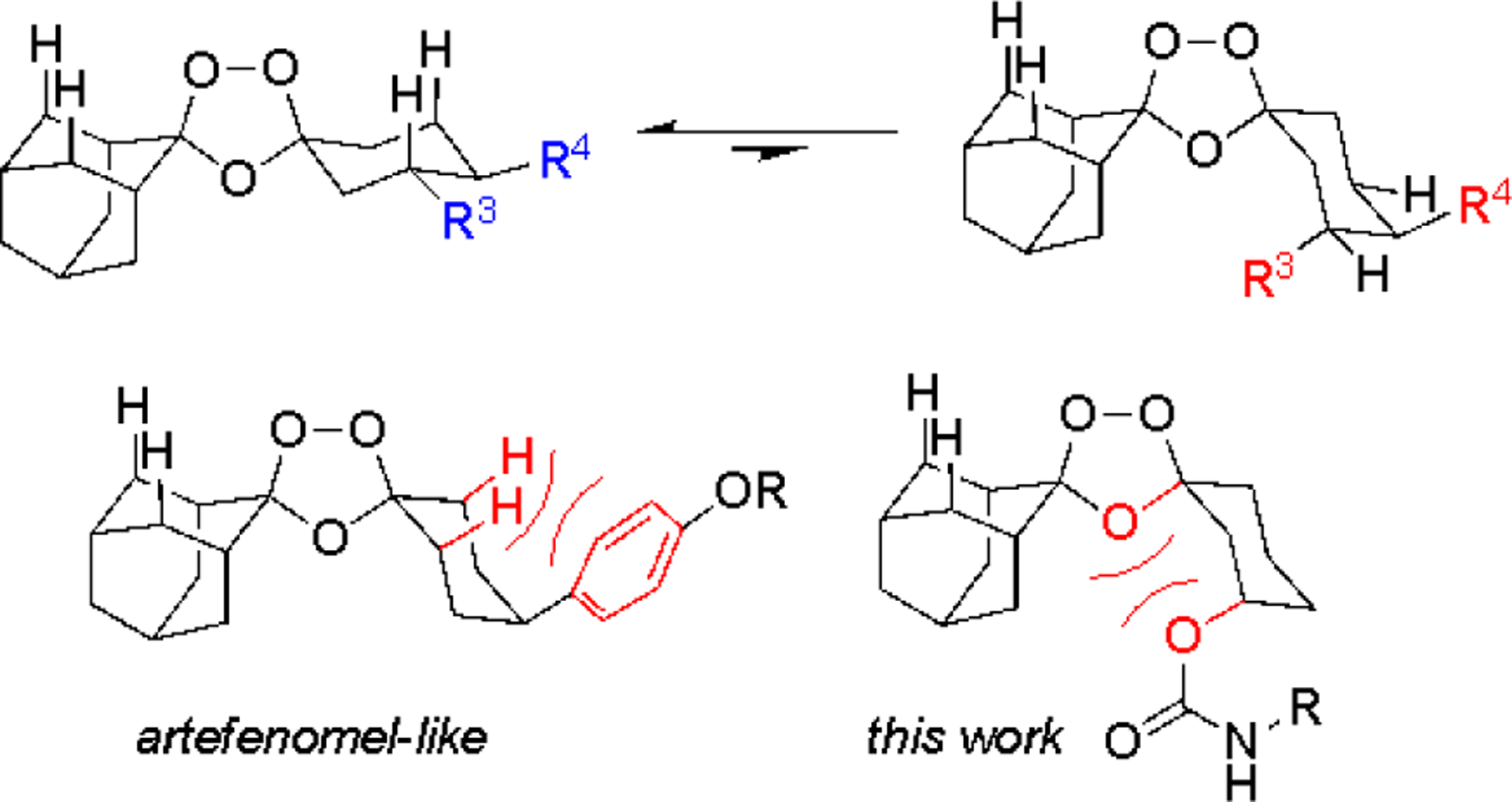

Figure 2.

Chemotypes explored by our laboratory previously13 and in the present communication.

Figure 3.

Iron reactivity is governed by conformational dynamics of the cyclohexane ring,12 with the peroxide-exposed conformer (top right) comprising the ferrous iron-reactive species. 1,3-Diaxial interactions (bottom in red) disfavor the iron-reactive conformer in artefenomel, and similarly in the trans-R3 carbamate analogs described in herein.

These encouraging findings compelled further exploration of the trans-R3 chemotype as described herein. In particular, we considered that a carbamate side chain at R3 might swing conformational dynamics in a favorable direction with respect to iron reactivity. Thus, much as the bulky aryl R4 substituent of OZ439/OZ609 is thought to reduce iron reactivity by disfavoring the peroxide-exposed conformer, so we reasoned might lone-pair–lone-pair interactions of the carbamate sp3 O-atom and O-4 of the trioxolane ring (Figure 3). The ultimate goal of such exploration, naturally, is to identify new molecules that combine the PK/PD profile of artefenomel with the more favorable drug-like properties (reduced MW and logD, enhanced solubility) of arterolane.

Here we describe the enantioselective synthesis of trans-R3 carbamate-substituted trioxolanes. We generally find these analogs to exhibit superior in vitro potency and in vivo efficacy when compared to their amide congeners, consistent with our design hypotheses. The combination of excellent physiochemical properties and promising pharmacodynamics argues for the further study of this chemotype in the search for new antimalarial drug candidates with enhanced properties.

Results and Discussion

We devised an asymmetric synthesis of the desired (R,R) and (S,S) forms of carbamate analogs leveraging our previous findings14 that Griesbaum co-ozonolysis of 3-substituted cyclohexanones proceeds with good selectivity for the trans diastereomer. Controlling both stereocenters thus requires access to non-racemic cyclohexanone starting materials. A known asymmetric borylation15 reaction of cyclohexenone with B2(pin)2, mediated by a CuCl/(S)-Taniaphos complex, afforded intermediate (R)-2 in yields of 89–91% (Scheme 1). The use of (R)-Taniaphos in turn afforded (S)-2 in similarly high yield. Oxidation of 2 with NaBO3 afforded intermediate 3, which was prone to undergo elimination and was best converted immediately to the silyl ether 4. Griesbaum co-ozonolysis reaction of 4 with two equivalents of adamantan-2-one O-methyloxime and ozone in CCl4 afforded the expected 1,2,4-trioxolane intermediate 5 in yields of 77–94%. As expected, 1H NMR analysis of 5 confirmed that the reaction proceeded with high diastereoselectivity (12:1 d.r). Deprotection of silyl ether 5 with TBAF in THF proceeded smoothly to give alcohol 6. Mosher ester analysis of intermediate alcohol 6 prepared via asymmetric and racemic routes confirmed the reported15 high enantioselectivity of the asymmetric borylation reaction (see Supporting Information).

Scheme 1.

Optimized enantiocontrolled synthetic route used to prepare analogs (R,R)-8a–n. The same route was used to prepare analogs (S,S)-9a–c, using (R)-Taniaphos in the first step.

To complete the synthesis of final analogs, alcohol 6 was activated as the p-nitrophenylcarbonate (7). Reaction of this key intermediate with primary or secondary amines afforded the final analogs (8a-n, 9a-c) in modest to excellent yields depending on the amine employed. A final, carefully controlled Boc deprotection step (AcCl, MeOH, 0°C) was required for analogs 8c/9c, 8j-k, and 8m-n. This new process is amenable to multi-gram laboratory scales and should serve to enable preclinical PK/PD and toxicological assessment of both enantiomeric forms. It is likely that drug candidates of this chemotype would be studied clinically as the racemate to reduce drug costs and leverage existing process routes to cis-R4 substituted agents like arterolane and artefenomel.

The new carbamate analogs were evaluated for antiplasmodial effect in the W2 strain using our standard protocol.16 With few exceptions, the carbamate analogs were found to be 2–3 fold more potent than amide-side chain congeners, modest differences that were nevertheless statistically significant (Chart 1). Carbamate enantiomer pairs 8a-c/9a-c were by contrast found to be essentially equipotent. The exceptional potency of analogs 8c and 8i bearing terminal primary amines inspired the synthesis of homologs 8j and 8k and ring contracted congeners 8m and 8n. These new analogs exhibited 2-fold weaker EC50 values than 8c, with the exception of aminopyrrolidine 8n, which mostly retained the excellent potency of the aminopiperidine progenitor. While most of the analogs explored bore basic amines intended to enhance aqueous solubility, the presence of such functionality was not required for potent activity (e.g., 8f and 8l).

Chart 1.

In vitro activity of 1a–i,13 8a–n, and 9a–c against W2 P. falciparum parasites (EC50 ± SEM). Reported EC50 values are the means of at least three determinations. EC50 values for controls used in specific experiments are indicated at bottom of figure.

Next we evaluated the physiochemical and ADME properties of select carbamate analogs, using as a benchmark the measured or reported10, 17 values for current clinical candidates OZ439, OZ609, and E209 (Table 1). As expected, the new carbamate analogs exhibited much more favorable LogD/cLogD (pH 7.4) values compared to the current candidates, and this translated to superior aqueous solubility. Selected analogs were assessed for human liver microsome (HLM) stability and analogs 8a/9a, 8b/9b, and 9c showed notably showed superior T1/2 and intrinsic clearance (CLint) values when compared to measured or reported values for OZ439 and E209, though all were inferior to values for the OZ609 control.

Table 1.

In vitro ADME data for selected analogs and controls.

| compound | HLM T1/2 (min) | HLM CLint (μL/min/mg) | MLM T1/2 (min) | MLM CLint (μL/min/mg) | Log D in octanol/PBS; pH 7.4 or cLogDd | Solubility in PBS pH 7.4 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OZ439a | 21.8 | 63.7 | 165 | 8.4 | 5.81; 5.5c | 0.181b |

| OZ609a | 180.4 | 7.7 | 451 | 3.1 | 5.14 | 94.3b |

| OZ277b | >60 | <7 | n.t | n.t | 2.6 | 504 |

| E209c | 68 | 25 | 132 | 13 | 6.4c; 5.5d | 0.112b |

| 8a | 108.4 | 12.8 | n.t. | n.t. | 1.6c | n.t. |

| 9a | >120 | <11.5 | n.t. | n.t. | 1.6c | 173.7 |

| 8b | 96.8 | 14.3 | n.t. | n.t. | 2.4c | n.t. |

| 9b | 64.8 | 21.4 | n.t. | n.t. | 2.4c | 164.1 |

| 8ca | 11.3 | 123 | 9.0 | 155 | 2.44; 1.1c | 144.5 |

| 9c | 117.4 | 11.8 | n.t. | n.t. | 1.1c | 118.0 |

| 8ea | 35.2 | 39.4 | 4.3 | 321 | 3.25; 3.3c | 157.0 |

| 8na | 30.3 | 45.8 | 9.4 | 147 | 2.89; 1.6c | 167.0 |

| verapamila | 9.4 | 147.6 | 5.2 | 268 | n.t. | n.t. |

| diclofenaca | n.t. | n.t. | n.t | n.t | n.t. | 199 |

data generated via Medicines for Malaria Venture.

data from ref 17.

data from ref 10.

cLogD (pH 7.4) calculated in Marvin Sketch v17.22 from ChemAxon.

We used the P. berghei mouse malaria model as a convenient means to assess the oral efficacy of selected new carbamate analogs, using arterolane (OZ277), 1a, or OZ439 as controls. The data presented in Table 2 reflects four separate studies examining different dosing paradigms in cohorts of five animals per compound/dosing arm, with animals judged to be cured if parasitemia could not be detected in blood smears at day 30. All regimens shown in Table 2 were well tolerated, with no overt signs of toxicity observed for any of the analogs studied. The data in experiment 1 is reproduced from our previous report,13 wherein we found that trans-R3 amide analogs such as 1a, and 1d, were at least as efficacious as OZ277 with four QD oral doses of 6 mg/kg. Experiment 2 was a bridge study designed to compare carbamate analogs 8a-e to arterolane and 1a, under a similar dosing schedule. We were pleased to find that the carbamate analogs were highly efficacious, the lone exception (8e) mirroring the similarly poor in vivo efficacy we observed13 for its direct amide congener 1e. Lowering the daily oral dose to just 2 mg/kg revealed the clear superiority of carbamate analogs 8a-d and 8i over arterolane and 1a. Reducing the number of daily doses of analog 8c led to fewer cures, although it was impressive that three, or even two QD doses at 4 mg/kg produced cures in some animals.

Table 2.

Oral efficacy of trans-R3 analogs and controls in P. berghei-infected female Swiss Webster mice.a

| compound | PO dose (days) | cures |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1b | ||

| OZ277 | 6 mg/kg/day (4 days) | 4/5 |

| 1a | 5/5 | |

| 1b | 0/5 | |

| 1c | 4/5 | |

| 1d | 5/5 | |

| 1e | 1/5 | |

| 1g | 0/5 | |

| Experiment 2 | ||

| OZ277 | 4 mg/kg/day (4 days) | 5/5 |

| 1a | 5/5 | |

| 8a | 5/5 | |

| 8b | 5/5 | |

| 8c | 5/5 | |

| 8d | 5/5 | |

| 8e | 0/5 | |

| OZ277 | 2 mg/kg/day (4 days) | 2/5 |

| 1a | 1/5 | |

| 8a | 5/5 | |

| 8b | 4/5 | |

| 8c | 5/5 | |

| 8d | 5/5 | |

| 8i | 4/5 | |

| 4 mg/kg/day | ||

| 8c | 4 days | 5/5 |

| 3 days | 4/5 | |

| 2 days | 1/5 | |

| 8c | 40 mg/kg (1 day) | 1/5 |

| 80 mg/kg (1 day) | 5/5 | |

| Experiment 3 | ||

| OZ439 | 40 mg/kg (1 day) | 5/5 |

| 8c | 3/5 | |

| 8j | 1/5 | |

| 8k | 2/5 | |

| 8n | 3/5 | |

| Experiment 4 | ||

| OZ439 | 40 mg/kg (1 day) | 5/5 |

| 8c | 5/5 | |

| 9c | 3/5 | |

Mice were judged cured if parasitemia was undetectable at day 30.

data reported previously in ref 13

Compound 8c administered in a single 40 mg/kg or 80 mg/kg dose was partially or fully curative, respectively. The OZ439 control cured all animals at 40 mg/kg, and has been reported4 to be effective at a single dose of just 20 mg/kg in this model. In experiment 3 we explored the single-exposure efficacy of analogs with 8c-inspired side chains, employing 8c and OZ439 as controls. At a single 40 mg/kg dose, analog 8n was just as effective as 8c (3/5 cures), superior to 8j and 8k, but again inferior to OZ439 (5/5 cures). In experiment 4 we compared analog 8c with its (S,S) form 9c, and found the former to be more efficacious than the latter. Some variability in inoculation challenge likely explains the variable efficacy of 8c between experiments 2–4 (e.g. ranging between 1 and 5 cures at 40 mg/kg). Valid comparisons can nonetheless be made between compounds in contemporaneous experiments, as we have been careful to do here.

To better understand the results of these in vivo studies, we considered the in vitro microsome stability data and further, generated mouse pharmacokinetic data for selected analogs (8c and 8n as ‘actives’; 8e as ‘inactive’). The superior in vivo efficacy of 8c and 8n when compared to 8e was consistent with more rapid metabolism of the latter in mouse liver microsomes (MLM), although 8c and 8n were also prone to metabolism by MLM. In a mouse PK study with oral dosing, compound 8e achieved ~three-fold lower systemic exposure than 8c or 8n (Table 3 and Supporting Information), a difference that seemed insufficient to fully explain the poor efficacy of this analog relative to 8c/8n. In this regard our findings echo those of a previous report18 describing the SAR effort leading to OZ439, which noted that curative efficacy in the P. berghei model was not well correlated with exposure as determined in PK studies. Despite this challenge, superior PK and PD were ultimately married in the form of OZ439, whereas currently available data for carbamate analogs like 8c and 8n suggest compounds with superior PD properties but a sub-optimal PK profile, at least in mice. The much more rapid elimination of 8c/8e/8b vs. OZ439 is apparent when comparing plasma-concentration time courses (Supporting Information).

Table 3.

Selected pharmacokinetic parameters for analogs 8c, 8e, 8n, and OZ439 following a single dose of 50 mg/kg by oral gavage in male CD-1 mice.

| compound | Tmax (hr) | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUClast (hr•ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OZ439 | 2 | 5660 ± 732 | 52600 ± 4810 |

| 8c | 2 | 631 ± 205 | 3430 ± 772 |

| 8e | 2 | 223 ± 25 | 1070 ± 127 |

| 8n | 2 | 594 ± 99 | 2800 ± 373 |

Ultimately PK in rodents is of secondary importance compared to PK in humans, and measures of human liver microsome (HLM) stability must be weighed alongside efficacy in mouse models. Although compound 8c became a focus of the in vivo studies detailed herein, compounds 8a/9a and 8b/9b in fact exhibit much more promising HLM CLint values, similar or even superior to those of current clinical candidates (Table 1). This is noteworthy, considering that the carbamate analogs also exhibit highly favorable cLogD values and superior aqueous solubility, the very properties that are highly sought in next-generation endoperoxide drug candidates. Further optimization and preclinical assessment of the chemotypes described herein therefore seems advisable.

Conclusions.

Here we described the stereocontrolled synthesis of ozonide-class antimalarials bearing trans-3” carbamate substitution of the cyclohexane ring, informed by conformational design principles. We find that prototypical trans-R3 carbamate analogs like 8a/9a combine excellent in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy with high aqueous solubility and good stability toward cultured human liver microsomes. It remains to be seen whether extended, artefenomel-like, exposure profiles can be achieved in these arterolane-like trans-R3 carbamates. Overcoming current, formidable challenges in drug formulation and a higher than preferable human dose, remains our long-term goal and is the focus of ongoing efforts.

METHODS

Materials.

All chemical reagents were obtained commercially and used without further purification, unless otherwise stated. Anhydrous solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. Solvents used for flash column chromatography and reaction work-up procedures were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher Scientific. Column chromatography was performed on Silicycle Sili-prep cartridges using a Biotage Isolera Four automated flash chromatography system.

Instrumentation.

NMR spectra were recorded on either a Varian INOVA 400 MHz spectrometer (with 5 mm Quad-Nuclear Z-Grad Probe), or a Bruker AvanceIII HD 400 MHz (with 5mm BBFO Z-gradient Smart Probe), calibrated to CH(D)Cl3 as an internal reference (7.26 and 77.00 ppm for 1H and 13C NMR spectra, respectively). Data for 1H NMR spectra are reported in terms of chemical shift (δ, ppm), multiplicity, coupling constant (Hz), and integration. Data for 13C NMR spectra are reported in terms of chemical shift (δ, ppm), with multiplicity and coupling constants in the case of C–F coupling. The following abbreviations are used to denote the multiplicities; s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, br = broad, app = apparent, or combinations of these. LC-MS and compound purity were determined using Waters Micromass ZQ 4000, equipped with a Waters 2795 Separation Module, Waters 2996 Photodiode Array Detector, and a Waters 2424 ELSD. Separations were carried out with an XBridge BEH C18, 3.5μm, 4.6 × 20 mm column, at ambient temperature (unregulated) using a mobile phase of water-methanol containing a constant 0.10 % formic acid.

Synthetic Procedures

(R)-3-((tert-butyldiphenylsilyl)oxy)cyclohexan-1-one (4).

A 200-mL round bottom flask equipped with a stirbar, rubber septum, and argon inlet was charged with (R)-3-hydroxycyclohexan-1-one15 (2.1 g, 18.4 mmol, 1.0 equiv), N,N-dimethylformamide (40 mL), and imidazole (2.51 g, 36.8 mmol, 2.0 equiv). The mixture was cooled at 0 °C while tert-butyl(chloro)diphenyl silane (5.3 mL, 20.2 mmol, 1.1 equiv) was added dropwise via syringe. The reaction mixture was allowed to slowly warm to rt. After stirring for 16 h, the reaction was judged complete based on TLC and LC/MS analysis. The reaction mixture was then diluted with EtOAc (100 mL) and DI H2O (100 mL). The organic phase was separated and washed with brine (2 × 50 mL), dried (MgSO4), filtered and concentrated to afford a colorless oil. The crude material was purified using flash column chromatography (330 g silica gel cartridge, 0–20% EtOAc–Hexanes, product eluted during 8% EtOAc–Hex) to give the desired ketone 4 (6.01 g, 17.05 mmol, 93%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.68–7.72 (m, 4 H), 7.39–7.49 (m, 6 H), 4.23 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 1 H), 2.47 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2 H), 2.35–2.42 (m, 1 H), 2.25–2.32 (m, 1 H), 2.17 (br dd, J = 8.5, 5.8 Hz, 1 H), 1.78–1.83 (m, 2 H), 1.64–1.71 (m, 1 H), 1.08–1.12 (s, 9 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 210.0, 135.8, 135.7, 134.9, 133.9, 133.6, 129.9, 129.8, 127.7, 127.7, 71.1, 50.4, 41.2, 32.9, 26.9, 26.6, 20.6, 19.2; MS (ESI) calcd for C22H29O2Si [M + H]+: m/z 353.19, found 353.46.

(1R,3”R)-tert-butyl((dispiro[adamantane-2,3’-[1,2,4]trioxolane-5’,1”-cyclohexan]-3”-yl)oxy) diphenylsilane (5).

A 200-mL recovery flask was charged with ketone (R)-4 (1.51 g, 4.28 mmol, ca. 1 equiv), carbon tetrachloride (100 mL), and O-methyl 2-adamantanone oxime (768 mg, 4.28 mmol, 1.0 equiv). The solution was cooled to 0 °C and sparged with O2 for 10 minutes. The reaction was maintained at 0 °C while ozone was bubbled (2 L/min, 40% power) through the solution. After stirring for 90 mins, the reaction was judged to be incomplete based on TLC and LC/MS analysis so additional oxime (0.386 g, 2.14 mmol, 0.5 equiv) was added in a single portion to the reaction mixture followed by additional carbon tetrachloride (50 mL). Ozone was bubbled through the reaction mixture for another 45 mins, after which a third portion of oxime (0.386 g, 2.14 mmol, 0.5 equiv) was added and ozone again bubbled through the reaction for a final 45 mins. The solution was then sparged with O2 for 10 minutes to remove any dissolved ozone, followed by sparging with argon gas for 10 minutes to remove any dissolved oxygen. The solution was then concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a viscous oil. The crude material was purified using flash column chromatography (120 g silica gel cartridge, 0–20% EtOAc–Hexanes, product eluted during 5% EtOAc–Hex) to give the desired trioxolane product 5 (2.01 g, 3.87 mmol, 91%, 12:1 dr) as a colorless semi-solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.69 (td, J = 7.7, 1.5 Hz, 4 H); 7.36–7.46 (m, 6 H), 3.89–3.96 (m, 1 H), 3.78–3.85 (m, 1 H), 1.95–2.05 (m, 3 H), 1.65–1.84 (m, 12 H), 1.46–1.65 (m, 3 H), 1.19–1.36 (m, 3 H), 1.08 (s, 9 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 135.8, 135.8, 134.5, 134.4, 129.6, 129.5, 127.6, 127.5, 111.2, 109.2, 69.8, 43.8, 36.8, 36.3, 36.2, 34.8, 34.4, 33.8, 33.2, 27.0, 26.9, 26.5, 19.9, 19.2; MS (ESI) calcd for C32H42NaO4Si [M + Na]+ m/z 541.28, found 541.56.

(1R,”R)-Dispiro[adamantane-2,3’-[1,2,4]trioxolane-5’,1”-cyclohexan]-3”-ol (6).

To a stirred solution of 5 (2.0 g, 3.86 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in THF (20 mL) was added a solution of tetrabutylammonium fluoride (1.0 M in THF, 19.2 ml, 19.3 mmol, 5.0 equiv) dropwise whilst stirring at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was allowed to slowly warm to rt and stirred for 12 h, at which point conversion was determined to be complete based on TLC and LC/MS analysis. The reaction was then diluted with brine (100 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (2 × 100 mL). The organic layer was then dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a yellow oil. The crude material was purified using flash column chromatography (80 g silica gel cartridge, 0–50% EtOAc–Hexanes, product eluted during 20% EtOAc–Hexanes) to yield the desired product 6 (1.01 g, 3.60 mmol, 93%) as a colorless solid: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.94–4.14 (m, 1 H), 2.47 (br s, 1 H), 2.07 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 1.90–2.05 (m, 7 H), 1.69–1.88 (m, 12 H), 1.47–1.63 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 111.9, 109.1, 67.9, 41.7, 36.7, 36.2, 36.2, 34.9, 34.9, 34.8, 34.7, 33.8, 33.1, 26.8, 26.4, 19.1; MS (ESI) calcd for C16H24O4 [M + H]+ m/z 281.17, found 281.51.

(1R,3”R)-Dispiro[adamantane-2,3’-[1,2,4]trioxolane-5’,1”-cyclohexan]-3”-yl (4-nitrophenyl) carbonate (7).

To an oven-dried round bottom flask containing a magnetic stir bar under an Ar(g) atmosphere was added alcohol 6 (0.150 mg, 0.54 mmol, 1.0 equiv), dichloromethane (10 mL), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.30 mL, 1.74 mmol, 3.25 equiv), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (0.078 g, 0.64 mmol, 1.2 equiv). The mixture was cooled to 0 °C while 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate (0.350 g, 1.74 mmol, 3.25 equiv) was added as a solid in two portions. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to rt and stirred for 3 h. The reaction was diluted with DI H2O (100 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (1 × 100 mL). The organic layer was washed repeatedly with 1 M aq K2CO3 solution until the aqueous layer was colorless and no longer yellow (indicating that most of the p-nitrophenol had been successfully removed from the organic layer). The organic layer was then dried (Na2SO4), filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to yield a viscous yellow oil. The crude material was purified using flash column chromatography (80 g silica gel cartridge, 0–25% EtOAc–Hexanes, product eluted during 10% EtOAc–Hex) to yield the desired product 7 (208 mg, 0.467 mmol, 87%) as a pale yellow oil (93:7 dr). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.26 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2 H), 7.38 (br d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2 H), 4.94 (td, J = 9.2, 4.5 Hz, 1 H, minor diastereomer), 4.79–4.88 (m, 1 H), 2.32–2.42 (m, 1 H), 2.10 (br d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H), 1.69–2.00 (m, 1 H), 1.64–2.01 (m, 17 H), 1.40–1.64 (m, 3 H), 1.20–1.28 (m, 1 H), 0.83–0.96 (m, 1 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.5, 151.6, 145.3, 125.3, 121.9, 121.7, 111.9, 108.3, 76.2, 39.5, 36.7, 36.3, 36.3, 34.8, 34.7, 34.7, 34.7, 33.5, 30.0, 26.8, 26.4, 19.5; MS (ESI) m/z [M+Na]+ calcd for C23H27NNaO8: 468.16; found 467.99.

Representative procedure for synthesis of final analogues 8a-b and 8d-i. (1R,3”R)-Dispiro[adamantane-2,3’-[1,2,4]trioxolane-5’,1”-cyclohexan]-3”-yl l (2-amino-2-methylpropyl)carbamate (8a). To a solution of 7 (50 mg, 0.112 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in dichloromethane (1.5 mL) was added Et3N (50 μL, 0.359 mmol, 3.2 equiv), followed by 1,2-diamino-2-methylpropane (60 μL, 0.561 mmol, 5.0 equiv) at rt. The bright yellow mixture was allowed to stir at rt for 3 h. The reaction was quenched with 1 M aq NaOH (20 mL) and diluted with EtOAc (30 mL). The organic phase was separated and washed with additional 1 M aq NaOH (4 × 30 mL) until the aqueous layer was colorless (indicating that p-nitrophenol had been successfully removed from the organic layer). The combined aqueous layers were then back extracted with EtOAc (1 × 30 mL). The combined organic layers were then washed with brine (20 mL), dried (MgSO4), filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified using flash column chromatography (12 g silica gel cartridge, 0–20% MeOH (containing 0.7 N NH3)/CH2Cl2, with the desired product eluting during 15% MeOH (containing 0.7 N NH3)/CH2Cl2). The fractions containing product were combined and lyophilized to give carbamate 8a (39.0 mg, 0.099 mmol, 88%) as a colorless solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 4.62–4.72 (m, 1H), 3.13–3.23 (m, 2H), 2.22–2.30 (m, 1H), 2.03 (br d, J = 12.7 Hz, 3H), 1.86–1.98 (m, 6H), 1.72–1.86 (m, 13H), 1.60–1.70 (m, 1H), 1.29–1.56 (m, 3H), 1.24 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, MeOD) δ 157.6, 111.4 (minor diastereomer), 111.2, 108.7, 108.5 (minor diastereomer), 71.4 (minor diastereomer), 71.1, 53.1, 49.6, 40.0, 39.6 (minor diastereomer), 36.4, 36.4, 36.4, 34.4, 33.4, 30.3, 29.4 (minor diastereomer), 27.0, 26.6, 23.7 (app d, J = 2.0 Hz), 19.5; MS (ESI) calculated for C21H35N2O5 [M + H]+: m/z 395.25, found 395.05.

(1R,3”R)-Dispiro[adamantane-2,3’-[1,2,4]trioxolane-5’,1”-cyclohexan]-3”-yl (3-amino-2,2-dimethylpropyl)carbamate (8b).

Prepared according to the standard procedure described above for 8a with the following modification: 2,2-dimethyl-1,3-propanediamine (59.1 mg, 0.561 mmol, 5.0 equiv) was added to the reaction as a solution in dichloromethane (0.5 mL). Purification via flash column chromatography (12 g silica gel cartridge, 0–75% EtOAc–Hexanes, followed by 0–20% MeOH (containing 0.7 N NH3)/CH2Cl2, with the desired product eluting during 15% MeOH (containing 0.7 N ammonia)/CH2Cl2) afforded carbamate 8b (45.9 mg, 0.112 mmol, 100%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 4.64 (tt, J = 10.0, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.97 (s, 2H), 2.41 (s, 2H), 2.29–2.14 (m, 1H), 2.08–1.98 (m, 2H), 1.98–1.87 (m, 5H), 1.87–1.68 (m, 11H), 1.65 (td, J = 12.8, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 1.48 (qt, J = 12.7, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 1.39–1.25 (m, 1H), 0.88 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, MeOD) δ 158.9, 112.5, 110.0, 72.1, 50.1, 48.6, 41.3, 37.8, 37.7, 35.8, 34.8, 31.7, 28.3, 27.9, 23.5, 20.8; MS (ESI) calcd for C22H36N2O5K [M + K]+: m/z 447.23, found 447.57.

(1R,3”R)-Dispiro[adamantane-2,3’-[1,2,4]trioxolane-5’,1”-cyclohexan]-3”-yl (2-aminoethyl) carbamate (8d).

Prepared according to the standard procedure described above for 8a with the following modification: ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (74.6 mg, 0.561 mmol, 5.0 equiv) was added to the reaction as a solution in dichloromethane (0.5 mL) and the reaction was stirred for 1 h. Purification was performed using flash column chromatography (12 g silica gel cartridge, 0–20% MeOH (containing 0.7 N NH3)/CH2Cl2, with the desired product eluting during 15% MeOH (containing 0.7 N ammonia)/CH2Cl2) to give carbamate 8d (31.3 mg, 0.085 mmol, 76%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 4.63 (tt, J = 9.9, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 3.19 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 2.75 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.28–2.14 (m, 1H), 2.08–1.98 (m, 2H), 1.98–1.87 (m, 5H), 1.87–1.68 (m, 11H), 1.63 (td, J = 12.8, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 1.54–1.40 (m, 1H), 1.40–1.27 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, MeOD) δ 158.6, 112.6, 110.0, 72.2, 43.4, 42.1, 41.3, 37.8, 37.8, 37.7, 35.8, 35.8, 34.7, 31.7, 28.4, 28.0, 20.8; MS (ESI) calcd for C19H30N2O5K [M + K]+: m/z 405.18, found 405.63.

(1R,3”R)-Dispiro[adamantane-2,3’-[1,2,4]trioxolane-5’,1”-cyclohexan]-3”-yl piperazine-1-carboxylate (8e).

Prepared according to the standard procedure described above for 8a with the following modification: piperazine (24.2 mg, 0.281 mmol, 2.5 equiv) was added to the reaction which was stirred at rt for 5 h. Purification via flash column chromatography (12 g silica gel cartridge, 0–75% EtOAc–Hexanes, followed by 0–20% MeOH (containing 0.7 N NH3)/CH2Cl2, with desired product eluting during 10% MeOH (containing 0.7 N ammonia)/CH2Cl2) afforded carbamate 8e (33.8 mg, 0.086 mmol, 77%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.86–4.96 (m, 1H, minor diastereomer), 4.72–4.85 (m, 1H), 3.35–3.52 (m, 4H), 2.81 (br s, 4H), 2.67 (br s, 1H), 2.09–2.25 (m, 1H), 1.86–2.02 (m, 8H), 1.62–1.81 (m, 13H), 1.46–1.56 (m, 1H), 1.31–1.42 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 154.6, 111.6, 108.6, 71.2, 45.6, 44.4, 39.8, 36.7, 36.3, 36.2, 34.9, 34.8, 34.6, 34.6, 34.1, 30.6, 26.9, 26.4, 19.5; MS (ESI) calcd for C21H32N2O5K [M + K]+: m/z 431.19, found 431.53.

(1R,3”R)-Dispiro[adamantane-2,3’-[1,2,4]trioxolane-5’,1”-cyclohexan]-3”-yl morpholine-4-carboxylate (8f).

Prepared according to the standard procedure described above for 8a with the following modifications: morpholine (25 μL, 0.281 mmol, 2.5 equiv) was added to the reaction, which was stirred at rt for 3.5 h. Purification via flash column chromatography (12 g silica gel cartridge, 0–50% EtOAc–Hexanes, with desired product eluting during 15% EtOAc–Hexanes) afforded carbamate 8f (43.5 mg, 0.111 mmol, 99%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 4.93–4.85 (m, 1H, minor diastereomer), 4.77 (tt, J = 9.1, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 3.71–3.55 (m, 4H), 3.54–3.35 (br s, 4H), 2.24–2.07 (m, 1H), 2.07–1.85 (m, 7H), 1.85–1.65 (m, 12H), 1.57–1.39 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, MeOD) δ 156.4, 112.7, 109.8, 73.1, 67.5, 40.5, 37.8, 37.7, 35.9, 35.8, 35.7, 35.7, 35.0, 31.4, 28.3, 27.9, 20.5; MS (ESI) calcd for C21H31NO6K [M + K]+: m/z 432.18, found 432.53.

(1R,3”R)-Dispiro[adamantane-2,3’-[1,2,4]trioxolane-5’,1”-cyclohexan]-3”-yl piperidine-1-carboxylate (8g).

Prepared according to the standard procedure described above for 8a with the following modifications: piperidine (28 μL, 0.281 mmol, 2.5 equiv) was added to the reaction which was stirred at rt for 2 h. Purification via flash column chromatography (12 g silica gel cartridge, 0–50% EtOAc–Hexanes, with desired product eluting during 10% EtOAc–Hexanes) afforded carbamate 8g (43.3 mg, 0.111 mmol, 99%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.90 (tt, J = 8.7, 4.4 Hz, 1H, minor diastereomer), 4.79 (tt, J = 9.3, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 3.52–3.25 (m, 4H), 2.25–2.11 (m, 1H), 2.06–1.85 (m, 7H), 1.85–1.61 (m, 12H), 1.61–1.43 (m, 7H), 1.43–1.32 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.7, 111.5, 108.6, 70.8, 44.6, 39.8, 36.7, 36.3, 36.2, 34.9, 34.8, 34.6, 34.5, 34.1, 30.6, 26.9, 26.4, 24.4, 19.5; MS (ESI) calcd for C22H33NO5K [M + K]+: m/z 430.20, found 430.57.

(1R,3”R)-Dispiro[adamantane-2,3’-[1,2,4]trioxolane-5’,1”-cyclohexan]-3”-yl 4-methyl piperazine-1-carboxylate (8h).

Prepared according to the standard procedure described above for 8a with the following modifications: 1-methylpiperazine (31.0 μL, 0.281 mmol, 2.5 equiv) was added to the reaction. Purification via flash column chromatography (12 g silica gel cartridge, 0–75% EtOAc–Hexanes, followed by 0–20% MeOH (containing 0.7 N NH3)/CH2Cl2, with desired product eluting during 5% MeOH (containing 0.7 N ammonia)/CH2Cl2) afforded carbamate 8h (24.8 mg, 0.061 mmol, 54%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.91 (tt, J = 8.3, 4.2 Hz, 1H, minor diastereomer), 4.79 (tt, J = 9.2, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 3.58–3.35 (m, 4H), 2.42–2.26 (m, 7H), 2.23–2.13 (m, 1H), 2.05–1.84 (m, 7H), 1.84–1.61 (m, 12H), 1.58–1.47 (m, 1H), 1.43–1.33 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.5, 111.5, 108.5, 71.2, 54.6, 46.0, 39.7, 36.7, 36.2, 36.2, 34.9, 34.8, 34.6, 34.5, 34.1, 30.5, 26.8, 26.4, 19.4; MS (ESI) calcd for C22H34N2O5K [M + K]+: m/z 445.21, found 445.55.

(1R,3”R)-Dispiro[adamantane-2,3’-[1,2,4]trioxolane-5’,1”-cyclohexan]-3”-yl [(trans)-4-aminocyclohexyl]carbamate (8i).

Prepared according to the standard procedure described above for 8a with the following modifications: dichloromethane was substituted for THF (2 mL) and trans-1,4-cyclohexanediamine (32 mg, 0.281 mmol, 2.5 equiv) was added to the reaction which was stirred for 1.5 h at rt. The reaction was quenched with 1M aq NaOH (20 mL) and extractions were performed with dichloromethane (1 × 30 mL) rather than EtOAc. Purification via flash column chromatography (12 g silica gel cartridge, 0–100% EtOAc–Hexanes, followed by 0–20% MeOH (containing 0.7 N NH3)/CH2Cl2, with the desired product eluting during 10–15% MeOH (containing 0.7 N ammonia)/CH2Cl2) afforded carbamate 8i (36.8 mg, 0.088 mmol, 78%) as a white foam. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 4.63 (tt, J = 9.8, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 3.45–3.27 (m, 1H), 2.78–2.60 (m, 1H), 2.26–2.13 (m, 1H), 2.10–1.99 (m, 2H), 1.99–1.88 (m, 9H), 1.88–1.70 (m, 11H), 1.64 (td, J = 12.7, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 1.56–1.42 (m, 1H), 1.40–1.19 (m, 5H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, MeOD) δ 157.6, 112.5, 110.0, 71.9, 54.8, 50.7, 50.7, 41.3, 37.8, 37.7, 35.8, 35.8, 34.8, 34.7, 32.5, 31.7, 28.3, 27.9, 20.8; MS (ESI) calcd for C23H37N2O5 [M + H]+: m/z 421.27, found 421.65.

(1R,3”R)-Dispiro[adamantane-2,3’-[1,2,4]trioxolane-5’,1”-cyclohexan]-3”-yl (2-amino-2-oxoethyl)carbamate (8l)

To a solution of carbonate 7 (54 mg, 0.121 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in dichloromethane (1.5 mL) was added glycinamide HCl (27.1 mg, 0.245 mmol, 2.0 equiv) followed by N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.1 μL, 0.574 mmol, 4.74 equiv) at rt. The resulting suspension was stirred for 3 h, after which it was determined that the reaction was not progressing. The solution was then purged with Ar(g) for 10 min to evaporate all volatile organic materials from the mixture before DMSO (0.50 mL) and Et3N (78 μL, 0.561 mmol, 4.6 equiv) were added to the reaction. The resultant homogenous yellow solution was stirred at rt for 3 h before being judged complete by TLC and LCMS. The reaction was then diluted with EtOAc (30 mL) and DI H2O (75 mL). Following separation of the layers, the organic layer was washed with satd aq NaHCO3 (2 × 30 mL) and the combined aqueous layers were back extracted with EtOAc (1 × 30 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine (1 × 20 mL), dried (Na2SO4), filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to a crude residue. Purification via flash column chromatography (12 g silica gel cartridge, 0–50% EtOAc–Hexanes, followed by 0–20% MeOH (containing 0.7 N NH3)/CH2Cl2, with desired product eluting during 15% MeOH (containing 0.7 N NH3)/CH2Cl2) afforded carbamate 8l (40.4 mg, 0.106 mmol, 88%) as a white foam. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 4.65 (tt, J = 10.1, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.74 (s, 2H), 2.30–2.18 (m, 1H), 2.10–1.87 (m, 7H), 1.87–1.68 (m, 11H), 1.63 (td, J = 12.8, 4.0 Hz, 1 H), 1.54–1.26 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, MeOD) δ 174.9, 158.4, 112.6, 110.0, 72.6, 44.4, 41.2, 37.8, 37.7, 35.8, 35.7, 34.7, 31.6, 28.3, 27.9, 20.8; MS (ESI) calcd for C19H28N2O6K [M + K]+: m/z 419.16, found 419.50.

Plasmodium falciparum EC50 determinations

The growth inhibition assay for P. falciparum was conducted as described previously16 with minor modifications. Briefly, P. falciparum strain W2 synchronized ring-stage parasites were cultured in human red blood cells in 96-well flat bottom culture plates at 37 °C, adjusted to 1% parasitemia and 2% hematocrit under an atmosphere of 3% O2, 5% CO2, 91% N2 in a final volume of 0.1 mL per well in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 0.5% Albumax, 2 mM L-glutamine and 100 mM hypoxanthine in the presence of various concentrations of inhibitors. Tested compounds were serially diluted 1:3 in the range 10,000 – 4.6 nM (or 1,000–0.006 nM for more potent analogs), with a maximum DMSO concentration of 0.1%. Following 48 hours of incubation, the cells were fixed by adding 0.1 ml of 2% formaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline, pH = 7.4 (PBS). Parasite growth was evaluated by flow cytometry on a FACsort (Becton Dickinson) equipped with AMS-1 loader (Cytek Development) after staining with 1 nM of the DNA dye YOYO-1 (Molecular Probes) in 100 mM NH4Cl, 0.1% Triton x-100 in 0.8% NaCl. Parasitemias were determined from dot plots (forward scatter vs. fluorescence) using CELLQUEST software (Becton Dickinson). EC50 values for growth inhibition were determined from plots of percentage control parasitemia over inhibitor concentration using GraphPad Prism software.

P. berghei Mouse Malaria Model

Female Swiss Webster Mice (~20 g body weight) were infected intraperitoneally with 106 P. berghei-infected erythrocytes collected from a previously infected mouse. Beginning 1 hour after inoculation the mice were treated once daily by oral gavage for 1–4 days with 100 μL of solution of test compound formulated in 10% DMSO, 40% [20% 2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin in water], and 50% PEG400. There were five mice in each test arm. Infections were monitored by daily microscopic evaluation of Giemsa-stained blood smears starting on day seven. Parasitemias were determined by counting the number of infected erythrocytes per 1000 erythrocytes. Body weight was measured over the course of the treatment. Mice were euthanized when parasitemia exceeded 50% or when weight loss of more than 15% occurred. Parasitemias, animal survival, and morbidity were closely monitored for 30 days post-infection when experiments were terminated.

Animal Welfare

No alternative to the use of laboratory animals is available for in vivo efficacy assessments. Animals were housed and fed according to NIH and USDA regulations in the Animal Care Facility at San Francisco General Hospital. Trained animal care technicians provide routine care, and veterinary staff are readily available. Euthanasia was performed when malarial parasitemias top 50%, a level that does not appear to be accompanied by distress, but predicts progression to lethal disease. Euthanasia was accomplished with CO2 followed by cervical dislocation. These methods are in accord with the recommendations of the Panel on Euthanasia of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Our studies are approved by the UCSF Committee on Animal Research.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis:

Here Blank, et. al. describe an antimalarial chemotype intended to combine the favorable physiochemical properties of arterolane with the superior pharmacodynamics of artefenomel. Design principles are detailed, as are in vitro and in vivo data for several analogs, including compound 8a which is curative in mouse malaria models with QD oral doses as low as 2 mg/kg.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

A. R. Renslo acknowledges funding from the US National Institutes of Health, R01 Grant AI105106. Pharmacokinetic studies were performed at SRI International with funding from NIAID preclinical services under DMID contract No. HHSN272201100022I. We thank Medicines for Malaria Venture for generating the ADME data reported in Table 1 for 8c, 8e, 8n, OZ439, and OZ609.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Detailed synthetic procedures and characterization for analogues 8j-n, 9a-c and Mosher ester of intermediate 6. Scans of 1H NMR, 13C NMR and LC/MS spectra for all final analogs. Bioanalytical data and time-concentration curves for PK studies.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Conflict of Interest

A.R.R. is a founder and reports equity in Tatara Therapeutics, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Malaria Report 2019, World Health Organization: Geneva, 2019. ISBN: 978-92-4-156572-1

- 2.Amaratunga C; Lim P; Suon S; Sreng S; Mao S; Sopha C; Sam B; Dek D; Try V; Amato R; Blessborn D; Song L; Tullo GS; Fay MP; Anderson JM; Tarning J; Fairhurst RM Dihydroartemisinin–Piperaquine Resistance in Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria in Cambodia: A Multisite Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 357–365. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00487-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birnbaum J; Scharf S; Schmidt S; Jonscher E; Hoeijmakers WAM; Flemming S; Toenhake CG; Schmitt M; Sabitzki R; Bergmann B; Fröhlke U; Mesén-Ramírez P; Blancke Soares A; Herrmann H; Bártfai R; Spielmann T, A Kelch13-defined endocytosis pathway mediates artemisinin resistance in malaria parasites. Science 2020, 367, 51–59. DOI: 10.1126/science.aax4735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charman SA; Arbe-Barnes S; Bathurst IC; Brun R; Campbell M; Charman WN; Chiu FC; Chollet J; Craft JC; Creek DJ; Dong Y; Matile H; Maurer M; Morizzi J; Nguyen T; Papastogiannidis P; Scheurer C; Shackleford DM; Sriraghavan K; Stingelin L; Tang Y; Urwyler H; Wang X; White KL; Wittlin S; Zhou L; Vennerstrom JL, Synthetic ozonide drug candidate OZ439 offers new hope for a single-dose cure of uncomplicated malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2011, 108, 4400–4405. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1015762108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Straimer J; Gnädig NF; Stokes BH,; Ehrenberger M; Crane AA; Fidock DA Plasmodium falciparum K13 Mutations Differentially Impact Ozonide Susceptibility and Parasite Fitness In Vitro. mBio 2017, 8:e00172–17. DOI: 10.1128/mBio.00172-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumgärtner F; Jourdan J; Scheurer C; Blasco B; Campo B; Mäser P; Wittlin S In vitro activity of anti-malarial ozonides against an artemisinin-resistant isolate. Malar J. 2017, 16, 45 DOI: 10.1186/s12936-017-1696-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walz A; Leroy D; Andenmatten N; Mäser P; Wittlin S Anti-malarial ozonides OZ439 and OZ609 tested at clinically relevant compound exposure parameters in a novel ring-stage survival assay. Malar J. 2019, 18, 427. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-3056-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salim M; Khan J; Ramirez G; Clulow AJ; Hawley A; Ramachandruni H; Boyd BJ Interactions of Artefenomel (OZ439) with Milk during Digestion: Insights into Digestion-Driven Solubilization and Polymorphic Transformations. Mol. Pharm 2018, 15, 3535–3544 DOI: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phyo AP; Jittamala P; Nosten FH; Pukrittayakamee S; Imwong M; White NJ; Duparc S; Macintyre F; Baker M; Möhrle JJ Antimalarial Activity of Artefenomel (OZ439), a Novel Synthetic Antimalarial Endoperoxide, in Patients with Plasmodium Falciparum and Plasmodium Vivax Malaria: An Open-Label Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 61–69. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00320-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Neill PM; Amewu RK; Charman SA; Sabbani S; Gnädig NF; Straimer J; Fidock DA; Shore ER; Roberts NL; Wong MH-L; Hong WD; Pidathala C; Riley C; Murphy B; Aljayyoussi G; Gamo FJ; Sanz L; Rodrigues J; Cortes CG; Herreros E; Angulo-Barturén I; Jiménez-Díaz MB; Bazaga SF; Martínez-Martínez MS; Campo B; Sharma R; Ryan E; Shackleford DM; Campbell S; Smith DA; Wirjanata G; Noviyanti R; Price RN; Marfurt J; Palmer MJ; Copple IM; Mercer AE; Ruecker A; Delves MJ; Sinden RE; Siegl P; Davies J; Rochford R; Kocken CHM; Zeeman AM; Nixon GL; Biagini GA, Ward SA A tetraoxane-based antimalarial drug candidate that overcomes PfK13-C580Y dependent artemisinin resistance. 2017, Nat. Commun 8, 15159 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms15159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vennerstrom JL; Arbe-Barnes S; Brun R; Charman SA; Chiu FC; Chollet J; Dong Y; Dorn A; Hunziker D; Matile H; McIntosh K; Padmanilayam M; Santo Tomas J; Scheurer C; Scorneaux B; Tang Y; Urwyler H; Wittlin S; Charman WN, Identification of an antimalarial synthetic trioxolane drug development candidate. Nature 2004, 430, 900–904. DOI 10.1038/nature02779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creek D; Charman W; Chiu FCK; Prankerd RJ; McCullough KJ; Dong Y; Vennerstrom JL; Charman SA Iron-Mediated Degradation Kinetics of Substituted Dispiro-1,2,4-Trioxolane Antimalarials. J. Pharm. Sci 2007, 96, 2945–2956. DOI: 10.1002/jps.20958. 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blank BR; Gut J; Rosenthal PJ; Renslo AR Enantioselective Synthesis and in Vivo Evaluation of Regioisomeric Analogues of the Antmalarial Arterolane. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 6400–6407. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontaine SD; DiPasquale AG; Renslo AR, Efficient and stereocontrolled synthesis of 1,2,4-trioxolanes useful for ferrous iron-dependent drug delivery. Org. Lett 2014, 16, 5776–5779. DOI: 10.1021/ol5028392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng X; Yun J Catalytic enantioselective boron conjugate addition to cyclic carbonyl compounds: a new approach to cyclic β-hydroxy carbonyls. Chem. Commun 2009, 6577–6569. DOI: 10.1039/B914207J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sijwali PS; Rosenthal PJ Gene disruption confirms a critical role for the cysteine protease falcipain-2 in hemoglobin hydrolysis by Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2004, 101, 4384–4389. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0307720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charman SA; Andreu A; Barker H; Blundell S; Campbell A; Campbell M; Chen G; Chiu FCK; Crighton E; Katneni K; Morizzi J; Patil R; Pham T; Ryan E; Saunders J; Shackleford DM; White KL; Almond L; Dickins M; Smith DA; Moehrle JJ; Burrows JN; Abla N An in vitro toolbox to accelerate anti-malarial drug discovery and development. Malar. J 2020, 19, 1 DOI: 10.1186/s12936-019-3075-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong Y; Wang X; Kamaraj S; Bulbule VJ; Chiu FCK; Chollet J; Dhanasekaran M; Hein CD; Papastogiannidis P; Morizzi J; Shackleford DM; Barker H; Ryan E; Scheurer C; Tang Y; Zhao Q; Zhou L; White KL; Urwyler H; Charman WN; Matile H; Wittlin S; Charman SA; Vennerstrom JL Structure-Activity Relationship of the Antimalarial Ozonide Artefenomel (OZ439). J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 2654–2668 DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.