Abstract

Microbial α-glucans produced by GH70 (glycoside hydrolase family 70) glucansucrases are gaining importance because of the mild conditions for their synthesis from sucrose, their biodegradability, and their current and anticipated applications that largely depend on their molar mass. Focusing on the alternansucrase (ASR) from Leuconostoc citreum NRRL B-1355, a well-known glucansucrase catalyzing the synthesis of both high- and low-molar-mass alternans, we searched for structural traits in ASR that could be involved in the control of alternan elongation. The resolution of five crystal structures of a truncated ASR version (ASRΔ2) in complex with different gluco-oligosaccharides pinpointed key residues in binding sites located in the A and V domains of ASR. Biochemical characterization of three single mutants and three double mutants targeting the sugar-binding pockets identified in domain V revealed an involvement of this domain in alternan binding and elongation. More strikingly, we found an oligosaccharide-binding site at the surface of domain A, distant from the catalytic site and not previously identified in other glucansucrases. We named this site surface-binding site (SBS) A1. Among the residues lining the SBS-A1 site, two (Gln700 and Tyr717) promoted alternan elongation. Their substitution to alanine decreased high-molar-mass alternan yield by a third, without significantly impacting enzyme stability or specificity. We propose that the SBS-A1 site is unique to alternansucrase and appears to be designed to bind alternating structures, acting as a mediator between the catalytic site and the sugar-binding pockets of domain V and contributing to a processive elongation of alternan chains.

Keywords: glucansucrase, alternan, biosourced, polysaccharide, GH70, polymerase, sugar-binding pockets, surface-binding site, processivity, alternansucrase, enzyme catalysis, enzyme mechanism, carbohydrate structure, biotechnology, dextran, green chemistry

In recent decades, microbial polysaccharides have gained attention as promising biosourced polymers that can be regularly supplied and are less sensitive to market and climate fluctuations than plant polymers (1, 2). In addition, today's progress in structure–function studies and engineering of polymerases allows us to better control their structures and by extension their physicochemical properties. In this field, the glucansucrases belonging to GH70 (family 70 of glycoside hydrolases) (3) are very interesting enzymes. These α-transglucosylases catalyze the formation of high-molar-mass (HMM) and low-molar-mass (LMM) homopolysaccharides of d-glucose from sucrose, a low-cost and abundant substrate. The panel of polymers produced by glucansucrases varies dramatically in terms of size, type, and arrangement of α-glycosidic linkages and degree of branching, with all these features defining polymer structural properties and, consequently, the range of ongoing or potential applications. Among them, dextran, an α-1,6-linked glucan, was the first microbial polymer to be commercialized and used as plasma substitute (4). Other applications of α-glucans are mainly in the biomedical and analytical fields, but they are also used as thickening agents for food and cosmetics or as flocculants for ore mining (5, 6). Recently, the α-1,3-linked α-glucan named mutan was proposed to be used for biomaterial applications (7, 8).

To produce size-defined α-glucans directly from sucrose and avoid fractionation steps, it seems essential to identify the molecular determinants involved in the control of polymer size. Since 2010, the 3D structure resolution of five different glucansucrases established that they all adopt a U-shaped fold made up by four domains (A, B, C, and IV), which are flanked by an additional domain V (9–13) formerly known as the glucan-binding domain (GBD). Structure–function studies that followed further showed that sugar-binding pockets in the domain V of at least three GH70 family enzymes—the branching sucrase GBD-CD2 that catalyzes α-1,2 branches formation in dextran, as well as the dextransucrase DSR-M from Leuconostoc citreum NRRL B-1299 and the dextransucrase DSR-OK from Oenococcus kitaharae—participate in polymer binding and were proposed to be involved in dextransucrase processivity leading to HMM polymer formation (12, 14, 15). Other residues located in the enzyme active site, particularly in subsites +2 or +3 (near subsites −1 and +1 where the glucosyl and fructosyl moieties of sucrose are accommodated, respectively (16)) were also found critical for HMM dextran formation in the dextransucrases DSR-S from Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-512F, GTF180 from Lactobacillus reuteri 180, and DSR-M from L. citreum NRRL B-1299 (17–19).

Surprisingly, additional surface (or secondary) binding sites more distant from the active site were never described in the domains A, B, or IV of GH70 dextransucrases, contrary to what was observed for GH13 enzymes, which belong to the same clan as the GH70 enzymes and for which the distant surface-binding sites were found to play a role in substrate targeting, allosteric regulation, and also processivity (20–24).

Given the structural diversity of α-glucans, we wondered whether the role of sugar-binding pockets in the synthesis of HMM dextran could be generalized to all glucansucrases, especially those producing polymers with a structure very different from that of dextran. With this in mind, we focused on the recombinant alternansucrase (ASR) from the L. mesenteroides NRRL B-1355 strain, recently reclassified as L. citreum (25), which stands out as a distinct GH70 glucansucrase synthesizing a polysaccharide made of alternating α-1,3- and α-1,6-linkages, named “alternan” (26). From sucrose, ASR catalyzes the synthesis of a bimodal population of alternan, one of high molar mass (∼1,700,000 g mol−1) and one of much lower molar mass (1300 g mol−1) (27). These two populations are formed during the early stage of the reaction, suggesting that ASR follows a semi-processive mechanism of polymerization involving polymer anchoring regions in the enzyme to facilitate HMM alternan formation (28). HMM alternan is more soluble in water and less viscous than dextran, making it a good substitute for gum arabic (29, 30). It was also recently shown to form nanoparticles of interest for biomedical applications (31) and to promote the proliferation, migration and differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (32). In addition, oligoalternans obtained by acceptor reaction with maltose (33–36) are hydrolyzed only by a limited number of microbial glycoside hydrolases such as isomaltodextranases (29) or alternanases (37) and are resistant to mammalian enzymes, which is of interest for applications as prebiotics.

Recently, the resolution of ASR 3D structure combined to mutagenesis and molecular docking unraveled the structural basis for α-1,3- and α-1,6-linkage specificity and for the alternance mechanism that is governed by the recognition of the terminal glucosidic linkage of the incoming acceptor, thanks to specific subsites (13). Several residues in the proximity of the active site were also found to be critical for HMM alternan formation. In particular, the replacement of Trp675 (subsite +2) and Trp543 (subsite +3′) by alanine resulted in 82 and 54% decreases of HMM polymer synthesis, respectively. In addition, four putative sugar-binding pockets (V-A, V-B, V-C, and V-D) homologous to those found in other GH70 family enzymes have been identified in ASR domain V. Surprisingly, removal of the entire domain V did not completely abolish polymer formation but reduced it by 86% (13).

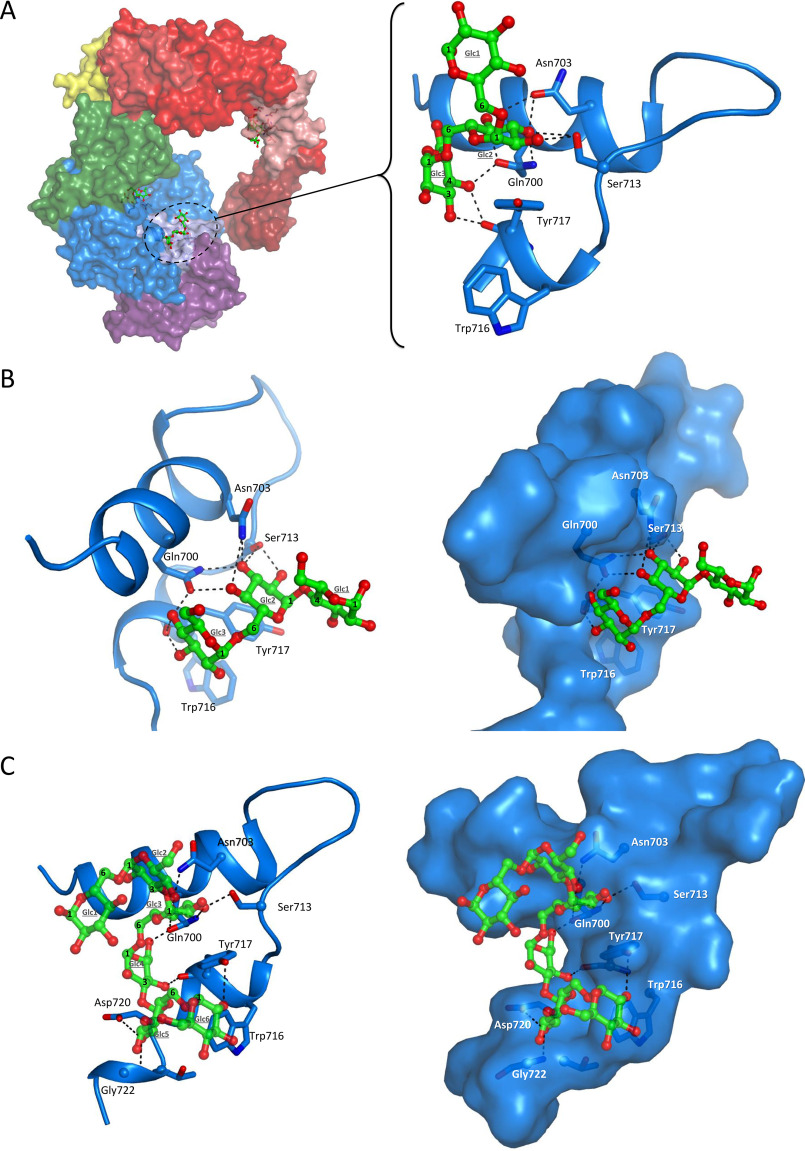

The control of polymer elongation by ASR is thus complex, involving residues of both the catalytic site and domain V. To get deeper insight in this mechanism, we placed our effort in the resolution of several ASR complexes. To this end, ASR crystals were soaked with different sugars varying in terms of degree of polymerization (DP) and glycosidic linkages. We obtained several complexes with different types of oligosaccharides bound in domains A and V. Combined with mutant characterization, the study highlighted the contribution of the domain V in HMM alternan formation and shed light on the importance of a new surface/secondary binding site found in domain A but remote from the catalytic core, which is defined by residues Tyr717 and Gln700 and was named SBS-A1.

Results

New complexes and identification of two sugar-binding sites: pocket V-B in domain V and SBS-A1 in domain A

To explore the structural determinants for alternan elongation, ASRΔ2 crystals were soaked with different acceptors varying in size and structures (Fig. 1). The following ligands were tested: glucose, isomaltose (I2), nigerose (α-d-Glcp-(1→3)-d-Glc), isomaltotriose (I3), panose, isomaltononaose (I9), isomaltododecaose (I12, α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-[α-d-Glcp-(1→6)]10-d-Glc), and a partially purified oligoalternan (OA) with a DP of ∼8 that contains 39% of α-1,3-linkages and 61% of α-1,6-linkages (Figs. S1 and S2).

Figure 1.

Identification of the new sugar-binding sites: SBS-A1 and sugar-binding pocket V-B in ASR. The list of ligands found at these binding sites is indicated in the right panel with an illustration of the structure visible in the complexes. Gray, catalytic residues Asp635, Glu673, and Asp767. See Figs. S4 and S7 for electron density maps sugar-binding pocket V-B and in surface-binding site A1, respectively.

For the complexes with I2, I3, panose, and OA, we unexpectedly observed a positive difference electron density in the domain A, in a site that we named surface-binding site A1 (SBS-A1) and that has never been described before in GH70 family enzymes (Fig. 1). For the same four ligands plus the I9, density was also observed in the domain V at a position corresponding to the sugar-binding pocket V-B (Gly234–Thr304) previously proposed to be a putative sugar-binding pocket (13). In contrast, no interpretable electron density was found in the pocket referred as V-A, also previously predicted to be a sugar-binding pocket. In all the complexes, the ASR crystallized in the space group P212121 with the presence of two protein molecules in the asymmetric unit and a very similar unit cell as the previously solved unliganded structure. Resolutions obtained are between 3.0 and 3.5 Å. Of note, in all the obtained complexes we will refer to the chain A in which the electron density is better defined. The glucosyl units of each oligosaccharide will be numbered in ascending order from their reducing end.

Domain V sugar-binding pockets: description and comparison

We used the I2 and I3 complexes for which we obtained the highest resolution (3.0 Å) to model the isomaltose and isomaltotriose that are bound in pocket V-B. Comparison with the high resolution structures of the branching sucrase GBD-CD2 from L. citreum NRRL B-1299 in complex with I2 and I3 helped the assignment of protein–ligand interactions (Fig. S3). The Glcp2 is in CH-π stacking interaction with Tyr241 (ASR numbering) and interacts with Gln278, Gln270, and Lys280 through O2, O3, and O1 atoms, respectively, and also with the main-chain oxygen of Thr297 through O3 (Fig. 2A and Fig. S4). The Glcp1 mainly interacts with the Thr249 through its O5 and with the Lys280 through O6 and O5 hydroxyls, which suggests that Lys280 is a pivotal residue for the recognition of isomaltose moiety, as already observed in branching sucrase GBD-CD2 and dextransucrase DSR-M structures. In the I3 complex, Glcp3 occupies the remaining part of the pocket, which is delimited by Asp266 and weakly interacts with Asp266 and Asn268. Although obtained at lower resolution (Fig. S4), the other complexes obtained in pocket V-B (panose, OA, and I9) have also been modeled on the basis of the already established I2–I3 interaction. Panose interacts mainly with its isomaltose moiety because the presence of the short α-1,4 linkage probably destabilizes the interaction between Lys280 and Glcp1. For the OA complex, only three monosaccharides could be modeled into the electron density, which has a different shape than the I3 molecule (Fig. S4). Assuming that an isomaltose moiety is still in interaction with Gln278/Gln280, this ligand has been modeled as one isomaltose moiety further decorated by an α-1,3-linked glucose on its nonreducing end (Fig. 2C). Unfortunately, the remaining part of the oligosaccharide is not visible, and the lower resolution of this complex does not allow a complete modeling of this interaction. Lastly, it should be observed that in all complexes two protein monomers are arranged around a pseudo 2-fold axis in the asymmetric unit, and the domain V of each unit is intertwined with its equivalent of the second chain. Only seven of nine glucosyl units of isomaltononaose are visible into electron density, and they appear to bind at the interface of the two pockets V-B of each chain (Fig. S5).

Figure 2.

Complexes in sugar-binding pockets. A, crystal structure of isomaltotriose binding in pocket V-B (PDB code 6SYQ). B, possible location of isomaltotriose in pocket V-A as superimposed from pocket V-B. C, crystal structure of the OA bound in pocket V-B (PDB code 6T18). The probable interaction network is displayed as dashed lines. D, sequence alignment of the sugar-binding pockets identified in ASR, DSR-M, and DSR-E glucansucrases. Pink highlighted residues were shown to directly interact with sugar ligands in 3D structures. Residues in blue ovals have been mutated to Ala in this study.

In our structures Gln270, Tyr241, Gln278, and Lys280 of pocket V-B are well-aligned with Gln186, Tyr158, Gln194, and Lys196 of pocket V-A (Fig. 2, A and B), whereas different residues are found in the pocket V-C (Fig. 2D and Fig. S6). On this basis we can propose that the sugar-binding pockets V-A and V-B are functional, whereas the pocket V-C is likely to be nonfunctional because of the absence of the QXK motif that, associated with a Tyr residue at the bottom of the pocket, was suggested to be a signature of sugar-binding pocket functionality (Fig. 2D) (12, 14). The structural comparison of pockets V-A and V-B revealed similarities but also subtle differences; in particular, the pocket V-A seems to be more open with a longer distance between the aromatic platform (Tyr158 OH) and the top of the pocket (Thr213 O) that might explain the reduced affinity for oligosaccharides, at least in the crystalline form (Fig. S6).

Mutation of the conserved tyrosine in the sugar-binding pockets of domain V

To further investigate the role of V-A and V-B pockets, the central stacking residues, Tyr158 and Tyr241, respectively, were replaced by an alanine. The mutations resulted in a slight decrease of the HMM polymer yield, from 31.5% for the WT to 27.2, 28, and 27.6% for the Y158A mutant, the Y241A mutant, and the Y158A/Y241A double mutant, respectively (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Enzyme specific activity, specificity, and melting temperature were not significantly affected for these three mutants (Table 1).

Figure 3.

HPSEC analysis of the mutants in the sugar-binding pockets of domain V. The reaction was from sucrose at 30 °C with 1 unit ml−1 of pure enzyme and 50 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.75.

Table 1.

Biochemical data of the characterized mutants. The reaction from sucrose only at 30 °C with 1 unit ml−1 of pure enzyme and 50 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.75, is shown. The specific activity of ASRΔ2 was 30.2 ± 1.0 units mg−1. Specific activity was determined in triplicate. The Tm was determined by differential scanning fluorimetry

| Residual activity | ΔTm with the WT enzyme | NMRa |

HPSEC |

Hydrolysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-1,3-Linkages | α-1,6-Linkages | Polymer formed (area) | tR polymer | ||||

| % | °C | % | % | % | min | % | |

| WT | |||||||

| ASRΔ2 | 100 ± 3.3 | 0 | 35 | 65 | 31.5 ± 1.6 | 37 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.4 |

| Mutations in domain V | |||||||

| ASRΔ2 Y158A (pocket V-A) | 80.2 ± 3.0 | +0.1 | 34 | 66 | 27.2 | 36.8 | 4.7 |

| ASRΔ2 Y241A (pocket V-B) | 78.4 ± 3.2 | +0.2 | 35 | 65 | 28.0 | 36.6 | 4.7 |

| ASRΔ2 Y158A/Y241A (pockets V-A + V-B) | 77.5 ± 2.4 | +0.2 | 33 | 67 | 27.6 | 36.5 | 4.7 |

| ASRΔ5 | 79.1 ± 2.7 | −2 | 30 | 70 | 4.5 | 38.2 | 5.8 |

| Mutations in SBS-A1 | |||||||

| ASRΔ2 N703A | 95.3 ± 6.0 | −0.1 | 35 | 65 | 33.5 | 36.9 | 4.3 |

| ASRΔ2 S713A | 95.8 ± 3.3 | −0.3 | 35 | 65 | 31.7 | 36.6 | 4.3 |

| ASRΔ2 W716A | 76.4 ± 7.0 | −1.0 | 35 | 65 | 30.0 | 36.4 | 5.0 |

| ASRΔ2 Q700A | 80.5 ± 2.8 | −0.2 | 35 | 65 | 20.4 | 35.7 | 5.6 |

| ASRΔ2 Y717A | 80.2 ± 2.4 | −0.1 | 33 | 67 | 18.8 | 35.6 | 5.2 |

| ASRΔ2 Q700A/Y717A | 26.1 ± 7.7 | −0.9 | 35 | 65 | 18.3 | 35.5 | 5.8 |

| Mutations in domain V + SBS-A1 | |||||||

| ASRΔ2 Y158A/Y717A | 62.9 ± 3.9 | −0.1 | 32 | 68 | 13.3 | 35.3 | 5.5 |

| ASRΔ2 Y241A/Y717A | 78.3 ± 5.8 | −0.2 | 31 | 69 | 8.5 | 35.4 | 5.9 |

| ASRΔ5 Y717A | 63.1 ± 3.6 | −2.4 | 30 | 70 | 2.3 | 36.4 | 6.2 |

a NMR was performed on crude reaction medium.

To explore the affinity of the enzyme with glucan, we performed affinity gel electrophoresis of ASRΔ2, dextransucrase DSR-M (C-terminally truncated form DSR-MΔ1 that includes sugar-binding pockets V-A, V-B, and V-C (12); Fig. 2D), and branching sucrase GBD-CD2 (N-terminally truncated form ΔN123-GBD-CD2 (38) that includes sugar-binding pockets V-J, V-K, and V-L (14); Fig. 2D) in native conditions. The two latter enzymes also possess functional sugar-binding pockets in which oligosaccharides were experimentally shown to bind. Logically, the migration of the three enzymes is delayed in the presence of dextran because enzyme sugar-binding pockets bind to a certain extent to the dextran-containing gel matrix. In contrast, only ASR was slightly retained by the presence of alternan in the gel (Fig. 4A). Focusing on ASR sugar-binding pockets, both single and double mutations Y158A (V-A) and Y241A (V-B) affected the binding ability of the enzyme with dextran and alternan, confirming a participation of the sugar-binding pocket stacking residue in glucan binding. A subtle difference is observed between the migration of Y158A and Y241A mutants in particular with the presence of alternan, with the Y241A mutant being almost not delayed (Fig. 4B). This suggests that the pocket V-B (Tyr241) has slightly more affinity than the pocket V-A and thus is in agreement with our complexes where we clearly see the presence of oligosaccharides only in the pocket V-B.

Figure 4.

Affinity gel electrophoresis. A, affinity gel electrophoresis of ASRΔ2, ASRΔ5, and ASRΔ5-Y717A. DSR-MΔ1 and ΔN123-GBD-CD2 (branching sucrase) are used as a positive control (12, 14). 1% BSA and protein standard (ladder) are used as negative controls. The gels were made in the presence or absence of 0.45% (w/v) dextran 70,000 g mol−1 or alternan. B, affinity gel electrophoresis of ASRΔ2, ASRΔ2-Y158A, ASRΔ2-Y241A, ASRΔ2-Y158A/Y241A, and ASRΔ5. Protein standard (ladder) is used as negative control. The gels were made in the presence or absence of 0.45% (w/v) dextran 2,000,000 g mol−1 or 0.9% (w/v) alternan.

Description of the surface-binding site identified in the domain A: SBS-A1

The SBS-A1 site was never described before for any other GH70 enzymes. To model the various ligands found in SBS-A1, we first sought to determine the direction of the sugar chain in the binding site. To do so, I2 was fitted in the electron density considering two possible orientations with either Glcp1 or Glcp2 in stacking interaction with Tyr717 (Fig. S7). The retained configuration corresponds to Glcp1 in stacking interaction with Tyr717 because this positioning sets the 1-6 glucosidic linkage in a low energy conformation (Fig. S8) and also allows the preferred interaction between α-d sugars and aromatic platforms, with the O1 pointing in the opposite direction of the stacking residue (39, 40). To further validate this binding mode, automatic docking of I2 has been performed, confirming that the lowest energy pose is with the Glcp1 in stacking interaction with Tyr717 (Fig. S7). A similar electron density was observed around Tyr717 for both the I3 and the panose complexes, suggesting that I2, I3, and panose all interact with their isomaltose moiety (Fig. S7). Concerning the oligoalternan and assuming that this molecule is composed of alternative α-1,6- and α-1,3-linkages, we modeled its visible part as an hexasaccharide and succeeded to fit in the electron density with the Glcp3 ring in stacking interaction with Tyr717 (Fig. S7). Lastly and interestingly, no electron density could be observed in SBS-A1 for the longer isomaltooligosaccharides (I9 and I12) that have been tested.

Isomaltotriose, isomaltose, and panose adopt a similar positioning

Four residues are found in interaction with I3 (Fig. 5A). Tyr717 is in CH-π stacking with Glcp2 (parallel configuration) and Glcp3 (T-shaped configuration). In addition, the O3 and O4 of Glcp3 interact with the main chain O of Tyr717 and with the side chain of Gln700. The O4 of Glcp2 interacts with Gln700 and Asn703; the O3 interacts with Gln700, Ser713, and Asn703; and the O2 interacts with Ser713 only. Glcp1 is not stabilized by any interactions with the protein. Glcp1 and Glcp2 of I2 superimpose well with Glcp2 and Glcp3 of I3 and are bound through the same network of interactions (Fig. S9). Panose binding involves the same four residues as those described for I2 or I3 complexes. Similarly, Glcp1 of panose is not maintained by any interactions (Fig. 5B). Noteworthy, we also attempted crystal soaking with glucose and nigerose but could not obtain any complex bound in SBS-A1. Hence, we suggest that at least two α-1,6-linked glucosyl units are required for a correct positioning around Tyr717: one in parallel and the other in T-shaped stacking interaction.

Figure 5.

Complexes in SBS-A1. A, crystal structure of isomaltotriose binding in surface-binding site A1 (PDB code 6SYQ). Sucrose molecule in the active site was positioned from the superimposition of the ASR catalytic domain with GTF-180–sucrose complex (PDB code 3HZ3). B, crystal structure of panose binding in SBS-A1 (PDB code 6T16). C, crystal structure of OA binding in SBS-A1 (PDB code 6T18).

Oligoalternan wraps around Tyr717

The glucosyl units Glcp2, Glcp3, and Glcp4 of the six visible glucosyl residues of the OA are in the same region as the three glucosyl residues of I3 and panose (Fig. 5C). The units Glcp1 and Glcp2 are unbound. The O3 of Glcp3 interacts with Ser713 and Gln700, and the O4 is coordinated with Gln700 and Asn703. There is a CH-π stacking interaction between Glcp3 and Tyr717 and also a T-shaped stacking interaction with Glcp4. The latter is also hydrogen-bonded with Gln700 through O6 and Tyr717 carbonyl through O4. The unit Glcp5 interacts with residues not identified previously with its O2 bound to Asp720 and the main chain of Gly722. Finally, the O2 of Glcp6 interacts only with the hydroxyl group of the Tyr717 side chain. For Glcp5 and Glcp6, there may also be a parallel-displaced stacking interaction with Trp716. It is noteworthy that Tyr717 is in interaction with Glcp3, Glcp4, and Glcp6. The OA literally wraps around this amino acid, making it a pillar residue of the SBS-A1–binding site.

The SBS-A1 is a mediator of HMM alternan formation

The five residues described in interaction with both I3 and OA (Gln700, Asn703, Ser713, Trp716, and Tyr717) were individually replaced by an alanine to evaluate their importance for enzyme specificity and polymer size distribution. The mutations did not affect the enzyme melting temperature, linkage specificity, or hydrolysis rate (Table 1). The specific activity was also globally well-conserved, with all mutants keeping between 76.4 and 95.8% of residual activity compared with WT ASRΔ2. The product profile was unchanged for the N703A, S713A, and W716A mutants (Fig. S10). In contrast, the polymerization process was clearly affected by the mutations of Gln700 and Tyr717, confirming the importance of these residues for oligosaccharide binding. Indeed, the amount of HMM polymer decreased from 31.5% for the WT enzyme to 20.4%, 18.8%, and 18.3%, respectively, for the Q700A and Y717A mutants and the Q700A/Y717A double mutant (Table 1 and Fig. 6A). The peak apex of HMM polymer formed with the mutants is also slightly displaced toward higher masses. This may reflect a possible variation of the polymer supramolecular organization as suggested by the dynamic light scattering assay used to compare the size distribution of WT and mutant alternan in solution. Indeed, the WT alternan has the ability to form nanoparticles with a diameter of ∼90 nm and low polydispersity, whereas the Y717A polymer is much more polydisperse and tends to aggregate (Fig. S11). This could be due to variation of branching length (among other possible reasons) even if the global percentage of α-1,3 linkages was unchanged compared with the WT alternan. Further analyses would be required to investigate the WT and mutant alternan structures in more detail and make conclusions. Note that alternan from ASRΔ2 and L. citreum ABK-1 alternansucrase (31) showed an almost identical nanoparticle size.

Figure 6.

Reaction product analysis of SBS-A1 mutants. A, HPSEC chromatograms of the products synthesized by SBS-A1 mutants. B, HPAEC-PAD chromatogram of the oligoalternans produced from sucrose with ASRΔ2 and mutant Y717A. The reaction was from sucrose at 30 °C with 1 unit ml−1 of pure enzyme and 50 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.75. C, HPAEC-PAD chromatogram of the acceptor reaction products from maltose, with ASRΔ2 and mutant Y717A. The reaction was from sucrose and maltose with sucrose:maltose mass ratio 2:1 at 30 °C with 1 unit ml−1 of pure enzyme and 50 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.75. For detailed structures, see “Experimental procedures.”

Chromatographic analysis by HPAEC-PAD of the sucrose reaction products obtained with ASRΔ2 and the Y717A mutant confirmed that the amount of oligosaccharides formed with the mutant is more abundant, hence corroborating the results of HPSEC (Fig. 6B). However, when performing the maltose acceptor reaction, the chromatograms of the reaction products for the 6 mutants were perfectly stackable to the WT, as shown for example for the Y717A mutant (Fig. 6C). These products result from maltose glucosylation and correspond to previously characterized oligoalternans with a maltose unit at the reducing end (13, 41).

To assess binding interactions with alternan or glucans, we performed affinity gel electrophoresis of ASRΔ5, which is a truncated form of ASR devoted of its domain V, or mutant ASRΔ5 Y717A in native conditions with dextran or alternan. The idea was to check whether the SBS-A1 site could confer affinity for dextran and alternan in the absence of domain V. We did not observe any differences between the ASRΔ5 and ASRΔ5-Y717A migration in the presence of dextran or alternan, indicating that the contribution of Tyr717 of SBS-A1 to glucan binding remains weaker than that conferred by Tyr158 or Tyr241 of sugar-binding pockets from domain V (Fig. 4A).

The Y717A mutation was combined with mutations of the stacking residues in the sugar-binding pocket of the domain V, Y158A and Y241A for pocket V-A and V-B, respectively. The resulting HMM alternan yield was reduced from 18.8% for the Y717A single mutant to 13.3 and 8.5% for the Y717A/Y158A and Y717A/Y241A double mutants, respectively (Fig. 7A). The mutations did not impact significantly the specificity, and the residual activity was higher than 60% for both mutants (Table 1). HMM polymer formation starts earlier with WT ASRΔ2 than with the mutant Y717A (∼5 and 10 min, respectively), and the production rate is almost twice as fast (0.50 and 0.27 g liter−1 min−1, respectively) (Fig. 7B and Fig. S12). In parallel, oligoalternans formation is enhanced with the mutant Y717A, which is in accordance with a reduced formation of HMM polymer (Fig. S13). Notably, HMM polymer formation rate is even lower for the double mutants Y717A/Y158A (pocket V-A) and Y717A/Y241A (pocket V-B). Mutation in pocket V-B affects the kinetics and yield of HMM polymer formation more than that in pocket V-A (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Analysis of mutants combined to the Y717A mutation. A, HPSEC chromatograms of alternan populations produced with Y717A and the double mutants Y717A/Y158A mutant (pocket V-A) and Y717A/Y241A mutant (pocket V-B). The reaction was from sucrose at 30 °C with 1 unit ml−1 of pure enzyme and 50 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.75. B, monitoring of polymer formation with time. The reaction was from sucrose at 30 °C with 1 unit ml−1 of pure enzyme and 50 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.75. The production rate was calculated from 5 to 75 min (R2 of 0.997) and from 10 to 75 min (R2 of 0.999) for ASRΔ2 and ASRΔ2 Y717A, respectively.

Discussion

We disclose here five crystal structures of alternansucrase in complex with different oligosaccharides. They are the first complexes ever obtained with this enzyme, a α-transglucosylase showing a unique linkage specificity among the GH70 glucansucrases by alternating α-1,6- and α-1,3-linkages. These structures enabled us to locate several oligosaccharide-binding sites in the enzyme. Two of them were located in the domain V, and a new site was identified in the domain A. We have investigated their role in the linkage specificity, the stability, and the ability to synthesize HMM alternans. It is important to emphasize the fact that this enzyme naturally catalyzes the synthesis of both HMM and LMM alternans. The idea behind this work was to identify structural parameters that could allow the design of ASR strictly specific for either HMM or LMM polymer synthesis in the future. What have we learned?

Involvement of ASR domain V and the sugar-binding pockets in HMM alternan formation

For all the complexes we solved, we have found isomaltooligosaccharides and oligoalternans bound in domain V. This domain shares a high percentage of identity with its counterpart exhibited by dextransucrase DSR-M. As for DSR-M, we have identified two sugar-binding pockets, V-A and V-B, showing the structural traits close to those previously described. We have found clear electron density for isomaltooligosaccharides in pocket V-B of alternansucrase. Affinity gel electrophoresis revealed that ASR binds dextran like dextransucrase DSR-M (12). More interestingly, we also found oligoalternans bound in pocket V-B and affinity gel confirmed the interaction between alternan and the domain V of the enzyme, thus demonstrating the binding promiscuity of this domain. In contrast, dextransucrase DSR-M and branching sucrase GBD-CD2 were not retained by alternan, showing that despite structural similarities, the sugar-binding pockets affinity could be subtly different from one enzyme to another. In particular, the positioning of isomaltooligosaccharide is different in both DSR-M and GBD-CD2 with the presence of a second aromatic platform (Tyr187 and Trp1849, respectively) that could prevent the orientation observed in ASR pocket V-B (Fig. S3). Lastly, in the complex with I9, the oligosaccharide seems to bind at the interface of the two domains V, giving a striking example of how multiple glucansucrase chains can simultaneously bind to a single polymer chain, and this is very likely to take place in solution.

Analysis of the complexes revealed the same interaction network as dextransucrase DSR-M and branching sucrase GBD-CD2 involving a QXK motif and a conserved aromatic residue with the oligosaccharides. Replacing the aromatic residues with alanine in each pocket induces a slight but significant effect on the HMM polymer yield (Table 1), indicating that these pockets may interact with the alternan chain and promote its elongation by providing anchoring platforms for long chains. Interestingly, mutations in the pockets were less detrimental to HMM alternan formation than deletion of the entire domain V (truncated mutant named ASRΔ5). ASRΔ5 synthesized only 4.5% of HMM polymer (13) versus 31.5% for ASRΔ2 and ∼27% for the single or double mutants targeting the aromatic residue of the sugar-binding pockets V-A and V-B. The mutation of only the conserved aromatic residue of the pockets (Tyr158 and Tyr241) may not be sufficient to totally abolish the interactions, even in the double mutant, and to obtain similar effect to an entire deletion. However, it should be noted that deletion of the entire domain V (removal of 481 residues, approximately one-third of the protein; Fig. S14) may also modify the folding of the other domains as suggested by lower melting temperature of ASRΔ5 variant (−2 °C compared with ASRΔ2), and this could have an impact on the production of HMM polymer. Altogether, our findings show that domain V plays a limited role in the formation of HMM polymer. Additional mutations targeting the conserved Gln and/or Lys of the QXK motif should help to make conclusions with more confidence regarding the role of the pockets in ASR domain V.

The surface-binding site A1, a signature of alternansucrase

SBS-A1 is the first functional surface-binding site described for a GH70 family enzyme, e.g. (i) located in the catalytic domain, (ii) where carbohydrates bound noncatalycally, and (iii) at a fixed position relative to the catalytic site. This is in agreement with the presence of surface-binding sites in GH13 and GH77 enzymes, which belong to the same GH-H clan as GH70 enzymes (20, 22).

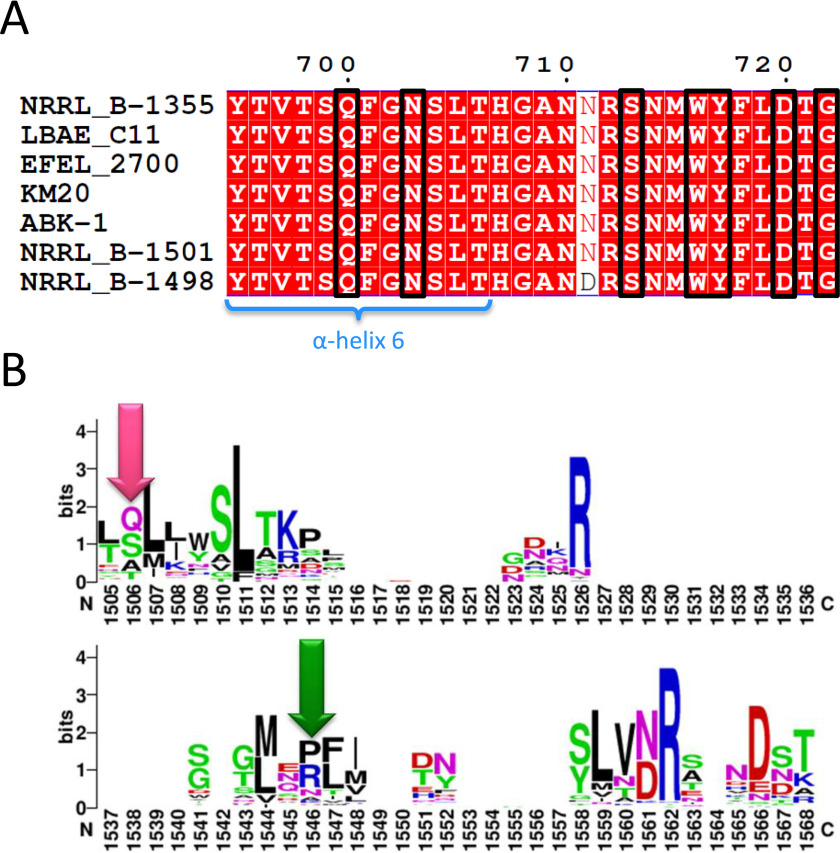

Of the various ligands tested in our soaking experiments, I2, I3, and panose did bind to SBS-A1 (Fig. 1), but nigerose, I9, and I12 did not (data not shown). A close inspection of the I3 complex revealed that in the proposed configuration, a fourth α-1,6-linked glucose could not be added to the nonreducing end of I3 because of a steric clash with the protein surface. In contrast, the addition of an α-1,3-linked glucose enables the steric clash to be avoided and also supports the proposed binding mode of the OA in Fig. 5C. The shape complementarity between protein surface and the OA indicates that the site is particularly well-designed to interact with oligosaccharides containing alternating α-1,6- and α-1,3-linkages above a DP of 4. Two residues appeared to be particularly important: Tyr717 and Gln700. Their replacement by Ala greatly reduced HMM polymer yield from 31.5% for ASRΔ2 to 18.8 and 20.4% for the mutants, showing that there is an important contribution of SBS-A1 to alternan elongation. In agreement with this assumption, mutagenesis of Tyr717 together with the deletion of domain V led to a further decrease of the percentage of HMM polymer produced from 4.5 to 2.3%. Thus, SBS-A1 would be involved in keeping the acceptor chain in close proximity to the catalytic site for further elongation, enhancing processivity, similarly to what was described for the GH13 amylosucrase of Neisseria polysaccharea (42), a transglucosidase that belongs to the same GH-H clan than ASR and uses sucrose as substrate to catalyze the formation of an amylose-like polymer. Finally, the glucosylation of short oligosaccharides (DP 3 to DP 6) seems not at all impacted by the mutations operated in SBS-A1, confirming that SBS-A1, which is remote from the active center, comes on stage only when the formed oligosaccharides reach a sufficient length. Furthermore, we propose the SBS-A1–binding site as a signature of alternansucrase specificity. Indeed, Gln700 and Tyr717 are conserved in all characterized (26, 31) and putative alternansucrase sequences identified by BLASTp search (from L. citreum NRRL B-1501, NRRL B-1498, LBAE-C11, KM20, and EFEL 2700 strains) (54) (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, of 64 characterized GH70 glucansucrases, residue Tyr717 is only found in alternansucrase sequences and is mainly replaced by an arginine (22 of 64) or a proline residue (20 of 64) in the other glucansucrases (Fig. 8B). Finally, a question remains: is there an interplay between SBS-A1 site and the domain V of ASR? To address this question, we constructed double mutants bearing the Y717A combined with mutation of the stacking tyrosine residue in each of the two pockets V-A and V-B. The HMM alternan yield changed from 31.5% (ASRΔ2) to 18.8% (Y717A) and further decreased to 13.3 and 8.5% for the Y158A/Y717A and Y241A/Y717A double mutants, respectively. This was also correlated with the slowdown of HMM alternan formation rate and provides evidence of an interplay between SBS-A1 and the sugar-binding pockets, in particular with the pocket V-B. Therefore, SBS-A1 could act as a molecular bridge, favoring oligosaccharide capture and the semi-processive mode of elongation as previously suggested by Moulis et al. (28). This hypothesis adds a further level of complexity in the role of surface-binding sites because not only do both the SBS-A1 and the domain V seem to have a role in processivity, but they also probably cooperate. This is in agreement with the observation that SBSs and carbohydrate binding modules frequently co-occur in carbohydrate active enzymes (23).

Figure 8.

SBS-A1 sequence comparison. A, alignment of the residues corresponding to SBS-A1 (in black boxes) in all characterized and putative alternansucrases. Only the strain name is indicated. The species was L. citreum or L. mensenteroides. Alignment created with ENDscript 2 (54). B, WebLogo of all GH70 characterized enzymes. The pink arrow corresponds to the Gln700 position, and the green arrow corresponds to the Tyr717 position.

Conclusion

To sum up, we described herein five new 3D structures of ASR in complex with different sugars (isomaltose, isomaltotriose, isomaltononaose, panose, and oligoalternan) bound either in domain A (SBS-A1) or in domain V (sugar-binding pocket V-B). The role of the domain V, as well as the new site SBS-A1 proposed as a signature of alternansucrase specificity, has been clarified. We have generated mutants quasi exclusively specific for the formation of oligoalternans (ASRΔ5-Y717A produces less than 3% of HMM alternan). Engineering alternansucrase for the exclusive formation of HMM alternan remains highly challenging. One might think to engineer the domain V and the sugar pockets to increase the affinity for alternan and shift the enzyme mechanism toward more processivity. Acquiring a clear vision of the interaction with a longer alternan chain and possibly during catalysis would be a major achievement. Because the resolution of crystal structures in complex with longer oligosaccharides (DP > 9) is likely to be very difficult, the use of different techniques such as time-resolved CryoEM and/or NMR could be of interest. Molecular dynamic simulations could also be performed to predict the positioning of long chains connecting the active site to the domain V via the site SBS-A1.

Experimental procedures

Production and purification of ASRΔ2 and ASRΔ5

ASRΔ2 and ASRΔ5 (Fig. S14) were produced from cultures of Escherichia coli BL21 DE3* transformed with plasmid pET53-asrΔ2 or pET53-asrΔ5 and purified using the conditions described in Ref. 13.

Crystallization and data collection

Crystals of ASRΔ2 were obtained using the conditions identified previously (13). The crystals were soaked in the reservoir solution complemented with 15% (v/v) ethylene glycol along with variable concentration of different oligosaccharide (Table 2). Isomaltose (α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-d-Glc), isomaltotriose (α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-d-Glc), and panose (α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→4)-d-Glc) were ordered from Carbosynth. Oligoalternan (α-(1→6)/α-(1→3) alternated) and isomaltononaose (α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-d-Glc) were purified in-house. The crystals were then directly cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen. To note, the soakings seemed to affect crystal integrity and data quality, especially those with longer ligands. This could explain the higher R-factors and also B-factors shown by some of our structures. Data collection was performed at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France) on Beamline ID23-1 for the isomaltose and panose complexes and at ALBA synchrotron (Barcelona, Spain) on Beamline XALOC for the isomaltotriose, isomaltononaose, and oligoalternan complexes. Diffraction images were integrated using XDS (43) and converted to structure factors using CCP4 programs (44). The structure was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER and the unliganded ASRΔ2 structure (PDB code 6HVG) as search model. To complete the model and build the oligosaccharides in the density, cycles of manual rebuilding using COOT (45) were alternated to restrained refinement using REFMAC5 (46). The structures were validated using MolProbity (47) and deposited in the Protein Data Bank. The data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table 2. The validation of oligosaccharide structures was done using the CARP server (RRID:SCR_009021) (48) and is shown in Fig. S8.

Table 2.

Crystallographic statistics. The values in parentheses refer to the high-resolution shell

| Enzyme |

pET53-His-ASRΔ2-Strep |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand | Isomaltose | Isomaltotriose | Panose | Oligoalternan | Isomaltononaose |

| PDB code | 6SZI | 6SYQ | 6T16 | 6T18 | 6T1P |

| Soaking concentration | 100 mm | 100 mm | 100 mm | 100 g/liter | 100 mm |

| Soaking duration | 1 min | 5 min | 5 min | 5 min | 5 min |

| Data collection | |||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9734 | 0.9793 | 0.9979 | 0.9793 | 0.9979 |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Molecules/asymmetric unit | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Cell constants (Å) | |||||

| a | 100.74 | 100.72 | 101.00 | 100.87 | 100.57 |

| b | 134.69 | 135.65 | 134.30 | 135.65 | 135.21 |

| c | 236.04 | 238.94 | 235.37 | 239.42 | 237.20 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.00–3.00 | 50.00–3.00 | 50.00–3.10 | 50.00–3.15 | 50.00–3.50 |

| Measured reflections | 440,819 | 352,514 | 275,779 | 255,328 | 187,213 |

| Unique reflections | 65,077 | 61,391 | 58,714 | 57,606 | 39,240 |

| Data completeness (%) | 99.9 | 92.4 | 99.7 | 99.9 | 94.9 |

| Rmerge | 0.11 (0.77) | 0.07 (0.77) | 0.10 (0.78) | 0.09 (0.72) | 0.14 (0.76)a |

| I/σ(I) | 6.1 (1.0) | 8.5 (1.0) | 6.7 (1.0) | 7.5 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.0) |

| CC1/2 | 0.99 (0.85) | 0.99 (0.82) | 0.99 (0.80) | 0.99 (0.71) | 0.99 (0.71) |

| Wilson B-factor (Ų) | 74.2 | 73.7 | 83.0 | 78.5 | 99.4a |

| Refinement | |||||

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.207/0.237 | 0.201/0.237 | 0.223/0.253 | 0.200/0.226 | 0.206/0.266a |

| RMSD | |||||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.009 |

| Angles (°) | 1.332 | 1.308 | 1.282 | 1.222 | 1.250 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%) | |||||

| Favored | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 |

| Allowed | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Outliers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of atoms | |||||

| Protein | 19,318 | 19,242 | 19,251 | 19,221 | 19,271 |

| Calcium | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Carbohydrates | 69 | 103 | 136 | 146 | 78 |

| Average B-factor (Ų) | 82.0 | 73.7 | 105.6 | 90.0 | 108.2a |

| CCall/CCfree | 0.94/0.92 | 0.95/0.93 | 0.94/0.92 | 0.94/0.92 | 0.94/0.89 |

| Clashscore (percentile) | 3 (100th) | 3 (100th) | 4 (100th) | 3 (100th) | 3 (100th) |

a Soakings, in particular those with longer ligands, affected diffraction quality and refinement statistics.

Automatic docking in the SBS-A1

Starting conformations for I2 were generated using the Carbohydrate Builder (RRID:SCR_018260). Receptor and ligand structures were prepared for docking with AutoDockTools (49, 50) and automatically docked with Vina-Carb (51) using standard settings.

Oligoalternan preparation for soaking experiments

Acceptor reactions with a sucrose:glucose mass ratio of 2:1 were set up in the same conditions as above to produce oligoalternans. Oligoalternans were partially purified by size-exclusion chromatography using two 1-m XK 26 columns (GE Healthcare) in series packed with Bio-Gel P6 and P2 resin (Bio-Rad) and water as eluent at 1 ml/min flow rate. The fraction used for soaking experiments was analyzed using HPAEC-PAD (Fig. S1), 1H NMR in the same conditions as described below, and MALDI-TOF-MS (Fig. S2). The molecular mass of the partially purified oligoalternan was determined in a Waters® MALDI-Micro MX-TOF mass spectrometer. The measurements were performed with the mass spectrometer in positive reflectron mode using an accelerating voltage of 12 kV. The mass spectra were acquired from 400 to 3000 m/z. The samples were dissolved in water (1 mg ml−1). A 0.75 ml of sample solution was mixed with 0.75 ml of the matrix solution (2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid 10 mg ml−1 in H2O:EtOH 0.5:0.5; v/v), and a total of 1.5 µl was applied to a stainless steel sample slide and dried at room temperature.

Site-directed mutagenesis study

The mutants were constructed by inverse PCR using the pET53-asr-Δ2 or pET53-asr-Δ5 genes as template, Phusion® polymerase (NEB), and the primers described in Table S1. Following overnight DpnI (NEB) digestion, the PCR product was transformed into competent E. coli DH5α, and clones were selected on solid LB medium supplemented with 100 µg ml−1 ampicillin. The plasmids were extracted with the Qiagen spin miniprep kit, and mutated asr genes were checked by sequencing (GATC Biotech). All mutants were produced and purified as described above.

Activity measurement

Activity was determined in triplicate at 30 °C in a Thermomixer (Eppendorf) using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid method (52). 50 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.75, 292 mm sucrose, and 0.05 mg ml−1 pure enzyme were used. One unit of activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that hydrolyzes 1 µmol of sucrose per minute.

Enzymatic reaction and product characterization

Polymer productions were performed using 1 unit ml−1 of pure enzyme with 292 mm sucrose in 50 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.75, at 30 °C over a period of 24 h. The products were analyzed using HPSEC with Shodex OH-Pak 805 and 802.5 columns in series in a 70 °C oven with a flow rate of 0.250 ml min−1 connected to a IOTA 2 refractive index detector (Precision Instruments). The eluent was 50 mm sodium acetate, 0.45 m sodium nitrate, and 1% (v/v) ethylene glycol. The polymer yield was calculated using the area of the peak corresponding to HMM glucan divided by the sum of the areas of all the peaks arising on the chromatogram.

The products were also analyzed by HPAEC-PAD using a CarboPac TM PA100 guard column upstream of a CarboPac TM PA100 analytical column (2 mm × 250 mm) at a flow rate of 0.250 ml min−1. The eluents were A: 150 mm NaOH and B: 500 mm sodium acetate with 150 mm NaOH. Sugars were eluted with an increasing 0 to 60% gradient of eluent B for 30 min Quantification was performed using standards of glucose and sucrose at 5, 10, 15, and 20 mg liter−1. The hydrolysis percentage was calculated by dividing the final molar concentration of glucose by the initial molar concentration of sucrose.

Acceptor reactions were set up in the presence of maltose (sucrose:maltose mass ratio, 2:1) using 1 unit ml−1 of pure enzyme with 292 mm sucrose in 50 mm NaAc buffer, pH 5.75, at 30 °C over a period of 24 h. The products were analyzed by HPAEC with the same conditions as described above. The structures corresponding to the nomenclature used are: OD4, α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→4)-d-Glc; OD5, α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→4)-d-Glc; OA4, α-d-Glcp-(1→3)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→4)-d-Glc; OA5, α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→3)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→4)-d-Glc; OA6, α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→3)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→4)-d-Glc; and α-d-Glcp-(1→3)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→3)-α-d-Glcp-(1→6)-α-d-Glcp-(1→4)-d-Glc.

NMR samples were prepared by dissolving 10 mg of the total products from sucrose in 0.5 ml of D2O. Deuterium oxide was used as the solvent, and sodium 2,2,3,3-tetradeuterio-3-trimethylsilylpropanoate was selected as the internal standard (δ1H = 0 ppm, δ13C = 0 ppm). 1H and δ13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 500-MHz spectrometer operating at 500.13 MHz for 1H NMR and 125.75 MHz for δ13C using a 5-mm z-gradient TB1 probe. The data were processed using TopSpin 3.0 software. 1D 1H NMR spectra were acquired by using a zgpr pulse sequence (with water suppression). Spectra were performed at 298 K with no purification step, for all mutants.

Dynamic light scattering was performed after the partial purification of the polymer using a 14-kDa cutoff cellulose dialysis tubing (Sigma) against water. The analysis was performed at 1% (w/v) in water with a DynaPro Nanostar instrument (Wyatt Corporation). The samples were pre-equilibrated for 1 mn at 25 °C and analyzed with a refractive index of 1.33, with 90° scattering optics at 658 nm.

Differential scanning fluorimetry was performed with 7 μm of pure enzyme in 50 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.75, supplemented with 0.5 g liter−1 of calcium chloride and 10× SYPRO orange (Life Technologies). A ramp from 20 to 80 °C was applied with 0.3 °C increments at the rate of 0.3 °C per second on a CX100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad).

Affinity gel electrophoresis

4 µg of purified enzyme were loaded in 6.5% (w/v) acrylamide gels containing from 0 to 0.9% (w/v) of 70-kDa dextran, 2000-kDa dextran (Sigma), or alternan produced by ASRΔ2 in the conditions described above. Alternan was purified by dialysis against water using a 14-kDa cutoff cellulose dialysis tubing (Sigma). BSA in 1% (w/v) of NaCl and ladder All Blue Standard were used as negative control (Bio-Rad). Migration was performed in mini PROTEAN system (Bio-Rad) for 30 min at 65 V followed by 2 h at 95 V in ice. The gels were stained with Colloidal Blue.

Multiple sequence alignment

Sequence alignment of putative sugar-binding pockets was performed using Clustal Omega (RRID:SCR_001591), inspected, and corrected manually using the structural superimposition of pockets V-A and V-B of ASR (PDB ID: 6HVG) and DSR-M (5NGY) and pocket V-L of GBD-CD2 (4TVD) to align the first aromatic residue. Then the alignment was submitted to WebLogo3 (RRID:SCR_010236) (53).

Data availability

The crystal structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank and are freely accessible under the accession numbers 6SZI, 6SYQ, 6T16, 6T18, and 6T1P. All the other data are contained within the article.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Metasys, the Metabolomics and Fluxomics Center at the Toulouse Biotechnology Institute (Toulouse, France) for the NMR experiments. We are grateful to the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France), the ALBA synchrotron (Barcelona, Spain), and the Structural Biophysics team of the Institute of Pharmacology and Structural Biology (Toulouse, France) for access to crystallization facilities and help in synchrotron data collection. We also thank the Engineering and Screening for Original Enzymes facility (ICEO), part of the Integrated Screening Platform of Toulouse, for access to HPLC and protein purification facilities. Technical assistance provided by Valérie Bourdon of the ICT-FR 2599 (Toulouse, France) is gratefully acknowledged.

This article contains supporting information.

Author contributions—M. M., C. M., G. C., and M. R.-S. conceptualization; M. M. and G. C. formal analysis; M. M., N. M., D. G., S. M., and G. C. investigation; M. M. and G. C. visualization; M. M., N. M., and G. C. methodology; M. M. writing-original draft; M. M., C. M., G. C., and M. R.-S. writing-review and editing; C. M., D. G., S. M., G. C., and M. R.-S. supervision; C. M. and M. R.-S. funding acquisition; M. R.-S. validation; M. R.-S. project administration.

Conflict of interest—The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- ASR

- alternansucrase

- HPSEC

- high-pressure size-exclusion chromatography

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- HMM

- high molar mass

- LMM

- low molar mass

- SBS

- surface-binding site

- GBD

- glucan-binding domain

- DP

- degree of polymerization

- I2

- isomaltose

- I3

- isomaltotriose

- I9

- isomaltononaose

- I12

- isomaltododecaose

- OA

- oligoalternan

- HPAEC-PAD

- high-pressure anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection.

References

- 1. Freitas F., Alves V. D., and Reis M. A. (2011) Advances in bacterial exopolysaccharides: from production to biotechnological applications. Trends Biotechnol. 29, 388–398 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moscovici M. (2015) Present and future medical applications of microbial exopolysaccharides. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1012 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lombard V., Golaconda Ramulu H., Drula E., Coutinho P. M., and Henrissat B. (2014) The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D490–D495 10.1093/nar/gkt1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moulis C., André I., and Remaud-Siméon M. (2016) GH13 amylosucrases and GH70 branching sucrases, atypical enzymes in their respective families. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 2661–2679 10.1007/s00018-016-2244-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leemhuis H., Pijning T., Dobruchowska J. M., van Leeuwen S. S., Kralj S., Dijkstra B. W., and Dijkhuizen L. (2013) Glucansucrases: three-dimensional structures, reactions, mechanism, α-glucan analysis and their implications in biotechnology and food applications. J. Biotechnol. 163, 250–272 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Soetaert W., Schwengers D., Buchholz K., and Vandamme E. J. (1995) A wide range of carbohydrate modifications by a single micro-organism: Leuconostoc mesenteroides. Prog. Biotechnol. 10, 351–358 10.1016/S0921-0423(06)80116-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dennes T. J., Perticone A. M., and Paullin J. L. (June 25, 2015) U.S. Patent 9,957,334

- 8. Paullin J. L., Perticone A. M., Kasat R. B., and Dennes T. J. (December 16, 2013) U.S. Patent 9,139,718

- 9. Vujičić-Žagar A., Pijning T., Kralj S., López C. A., Eeuwema W., Dijkhuizen L., and Dijkstra B. W. (2010) Crystal structure of a 117 kDa glucansucrase fragment provides insight into evolution and product specificity of GH70 enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21406–21411 10.1073/pnas.1007531107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ito K., Ito S., Shimamura T., Weyand S., Kawarasaki Y., Misaka T., Abe K., Kobayashi T., Cameron A. D., and Iwata S. (2011) Crystal structure of glucansucrase from the dental caries pathogen Streptococcus mutans. J. Mol. Biol. 408, 177–186 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pijning T., Vujičić-Žagar A., Kralj S., Dijkhuizen L., and Dijkstra B. W. (2012) Structure of the α-1,6/α-1,4-specific glucansucrase GTFA from Lactobacillus reuteri 121. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 68, 1448–1454 10.1107/S1744309112044168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Claverie M., Cioci G., Vuillemin M., Monties N., Roblin P., Lippens G., Remaud-Siméon M., and Moulis C. (2017) Investigations on the determinants responsible for low molar mass dextran formation by DSR-M dextransucrase. ACS Catal. 7, 7106–7119 10.1021/acscatal.7b02182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Molina M., Moulis C., Monties N., Pizzut-Serin S., Guieysse D., Morel S., Cioci G., and Remaud Siméon M. (2019) Deciphering an undecided enzyme: investigations of the structural determinants involved in the linkage specificity of alternansucrase. ACS Catal. 9, 2222–2237 10.1021/acscatal.8b04510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brison Y., Malbert Y., Czaplicki G., Mourey L., Remaud-Siméon M., and Tranier S. (2016) Structural insights into the carbohydrate binding ability of an α-(1→2) branching sucrase from glycoside hydrolase family 70. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 7527–7540 10.1074/jbc.M115.688796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Claverie M., Cioci G., Vuillemin M., Bondy P., Remaud-Simeon M., and Moulis C. (2020) Processivity of dextransucrase synthesizing very high molar mass dextran is mediated by sugar-binding pockets in domain V. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 5602–5613 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davies G. J., Wilson K. S., and Henrissat B. (1997) Nomenclature for sugar-binding subsites in glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem. J. 321, 557–559 10.1042/bj3210557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Claverie M., Cioci G., Guionnet M., Schörghuber J., Lichtenecker R., Moulis C., Remaud-Siméon M., and Lippens G. (2019) Futile encounter engineering of the DSR-M dextransucrase modifies the resulting polymer length. Biochemistry 58, 2853–2859 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Irague R., Tarquis L., André I., Moulis C., Morel S., Monsan P., Potocki-Véronèse G., and Remaud-Siméon M. (2013) Combinatorial engineering of dextransucrase specificity. PLoS One 8, e77837 10.1371/journal.pone.0077837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meng X., Pijning T., Tietema M., Dobruchowska J. M., Yin H., Gerwig G. J., Kralj S., and Dijkhuizen L. (2017) Characterization of the glucansucrase GTF180 W1065 mutant enzymes producing polysaccharides and oligosaccharides with altered linkage composition. Food Chem. 217, 81–90 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.08.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cuyvers S., Dornez E., Delcour J. A., and Courtin C. M. (2012) Occurrence and functional significance of secondary carbohydrate binding sites in glycoside hydrolases. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 32, 93–107 10.3109/07388551.2011.561537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wilkens C., Svensson B., and Møller M. S. (2018) Functional roles of starch binding domains and surface binding sites in enzymes involved in starch biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 01652 10.3389/fpls.2018.01652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cockburn D., Wilkens C., Ruzanski C., Andersen S., Willum Nielsen J., Smith A. M., Field R. A., Willemoës M., Abou Hachem M., and Svensson B. (2014) Analysis of surface binding sites (SBSs) in carbohydrate active enzymes with focus on glycoside hydrolase families 13 and 77: a mini-review. Biologia 69, 705–712 10.2478/s11756-014-0373-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cockburn D., and Svensson B. (2013) Surface binding sites in carbohydrate active enzymes: an emerging picture of structural and functional diversity. In Carbohydrate Chemistry (Lindhorst T. K., and Rauter A. P.) pp. 204–221, Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, UK [Google Scholar]

- 24. Skov L. K., Mirza O., Sprogøe D., Dar I., Remaud-Simeon M., Albenne C., Monsan P., and Gajhede M. (2002) Oligosaccharide and Sucrose Complexes of Amylosucrase: structural implications for the polymerase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 47741–47747 10.1074/jbc.M207860200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bounaix M.-S., Gabriel V., Robert H., Morel S., Remaud-Siméon M., Gabriel B., and Fontagné-Faucher C. (2010) Characterization of glucan-producing Leuconostoc strains isolated from sourdough. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 144, 1–9 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Côté G. L., and Robyt J. F. (1982) Isolation and partial characterization of an extracellular glucansucrase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-1355 that synthesizes an alternating (1→6),(1→3)-α-d-glucan. Carbohydr. Res. 101, 57–74 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)80795-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Joucla G., Pizzut S., Monsan P., and Remaud-Siméon M. (2006) Construction of a fully active truncated alternansucrase partially deleted of its carboxy-terminal domain. FEBS Lett. 580, 763–768 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moulis C., Joucla G., Harrison D., Fabre E., Potocki-Veronese G., Monsan P., and Remaud-Siméon M. (2006) Understanding the polymerization mechanism of glycoside-hydrolase family 70 glucansucrases. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 31254–31267 10.1074/jbc.M604850200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Côté G. L. (1992) Low-viscosity α-d-glucan fractions derived from sucrose which are resistant to enzymatic digestion. Carbohydr. Polym. 19, 249–252 10.1016/0144-8617(92)90077-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leathers T. D., Nunnally M. S., and Côté G. L. (2009) Modification of alternan by dextranase. Biotechnol. Lett. 31, 289–293 10.1007/s10529-008-9866-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wangpaiboon K., Padungros P., Nakapong S., Charoenwongpaiboon T., Rejzek M., Field R. A., and Pichyangkura R. (2018) An α-1,6-and α-1,3-linked glucan produced by Leuconostoc citreum ABK-1 alternansucrase with nanoparticle and film-forming properties. Sci. Rep. 8, 8340 10.1038/s41598-018-26721-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Charoenwongpaiboon T., Supraditaporn K., Klaimon P., Wangpaiboon K., Pichyangkura R., Issaragrisil S., and Lorthongpanich C. (2019) Effect of alternan versus chitosan on the biological properties of human mesenchymal stem cells. RSC Adv. 9, 4370–4379 10.1039/C8RA10263E [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Côté G. L., Holt S. M., and Miller-Fosmore C. (2003) Prebiotic oligosaccharides via alternansucrase acceptor reactions. In Oligosaccharides in Food and Agriculture, pp. 76–89, ACS Symposium Series, American Chemical Society, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hernandez-Hernandez O., Côté G. L., Kolida S., Rastall R. A., and Sanz M. L. (2011) In vitro fermentation of alternansucrase raffinose-derived oligosaccharides by human gut bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 10901–10906 10.1021/jf202466s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Holt S. M., Miller-Fosmore C. M., and Côté G. L. (2005) Growth of various intestinal bacteria on alternansucrase-derived oligosaccharides. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 40, 385–390 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01681.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sanz M. L., Côté G. L., Gibson G. R., and Rastall R. A. (2005) Prebiotic properties of alternansucrase maltose-acceptor oligosaccharides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 5911–5916 10.1021/jf050344e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Biely P., Côté G. L., and Burgess‐Cassler A. (1994) Purification and properties of alternanase, a novel endo-α-1,3-α-1,6-d-glucanase. Eur. J. Biochem. 226, 633–639 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brison Y., Pijning T., Malbert Y., Fabre É., Mourey L., Morel S., Potocki-Véronèse G., Monsan P., Tranier S., Remaud-Siméon M., and Dijkstra B. W. (2012) Functional and structural characterization of α-(1→2) branching sucrase derived from DSR-E glucansucrase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 7915–7924 10.1074/jbc.M111.305078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Asensio J. L., Ardá A., Cañada F. J., and Jiménez-Barbero J. (2013) Carbohydrate–aromatic interactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 946–954 10.1021/ar300024d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hudson K. L., Bartlett G. J., Diehl R. C., Agirre J., Gallagher T., Kiessling L. L., and Woolfson D. N. (2015) Carbohydrate–aromatic interactions in proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 15152–15160 10.1021/jacs.5b08424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Côté G. L., and Sheng S. (2006) Penta-, hexa-, and heptasaccharide acceptor products of alternansucrase. Carbohydr. Res. 341, 2066–2072 10.1016/j.carres.2006.04.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Albenne C., Skov L. K., Tran V., Gajhede M., Monsan P., Remaud‐Siméon M., and André-Leroux G. (2006) Towards the molecular understanding of glycogen elongation by amylosucrase. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 66, 118–126 10.1002/prot.21083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kabsch W. (2010) XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 10.1107/S0907444909047337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Winn M. D., Ballard C. C., Cowtan K. D., Dodson E. J., Emsley P., Evans P. R., Keegan R. M., Krissinel E. B., Leslie A. G. W., McCoy A., McNicholas S. J., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S., Potterton E. A., Powell H. R., et al. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242 10.1107/S0907444910045749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Emsley P., and Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 10.1107/S0907444904019158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Murshudov G. N., Skubák P., Lebedev A. A., Pannu N. S., Steiner R. A., Nicholls R. A., Winn M. D., Long F., and Vagin A. A. (2011) REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 355–367 10.1107/S0907444911001314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Williams C. J., Headd J. J., Moriarty N. W., Prisant M. G., Videau L. L., Deis L. N., Verma V., Keedy D. A., Hintze B. J., Chen V. B., Jain S., Lewis S. M., Arendall W. B. 3rd, Snoeyink J., Adams P. D., et al. (2018) MolProbity: more and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 27, 293–315 10.1002/pro.3330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lütteke T., Frank M., and von der Lieth C.-W. (2005) Carbohydrate Structure Suite (CSS): analysis of carbohydrate 3D structures derived from the PDB. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D242–D246 10.1093/nar/gki013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morris G. M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M. F., Belew R. K., Goodsell D. S., and Olson A. J. (2009) AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791 10.1002/jcc.21256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sanner M. F. (1999) Python: a programming language for software integration and development. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 17, 57–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nivedha A. K., Thieker D. F., Makeneni S., Hu H., and Woods R. J. (2016) Vina-Carb: improving glycosidic angles during carbohydrate docking. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 892–901 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Miller G. L. (1959) Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 31, 426–428 10.1021/ac60147a030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J.-M., and Brenner S. E. (2004) WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 10.1101/gr.849004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Robert X., and Gouet P. (2014) Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324 10.1093/nar/gku316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The crystal structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank and are freely accessible under the accession numbers 6SZI, 6SYQ, 6T16, 6T18, and 6T1P. All the other data are contained within the article.