Abstract

This review analyzes recent mechanistic studies that have provided new insights into how the structure of a metal complex influences the rate and selectivity of base-assisted C–H cleavage. Partitioning a broader mechanistic continuum into classes delimited by the polarization between catalyst and substrate during C–H cleavage is postulated as a method to identify catalysts favoring electrophilic or nucleophilic reactivity patterns, which may be predictive based on structural features of the metal complex (i.e., oxidation state, d-electron count, charge). Multi-metallic cooperativity and polynuclear speciation also provide new avenues to affect energy barriers for C–H cleavage and site selectivity beyond the limitations of single metal catalysts. An improved understanding of mechanistic nuances and structure-activity relationships on this important bond activation step carries important implications for efficiency and controllable site selectivity in non-directed C–H functionalization.

1. Introduction

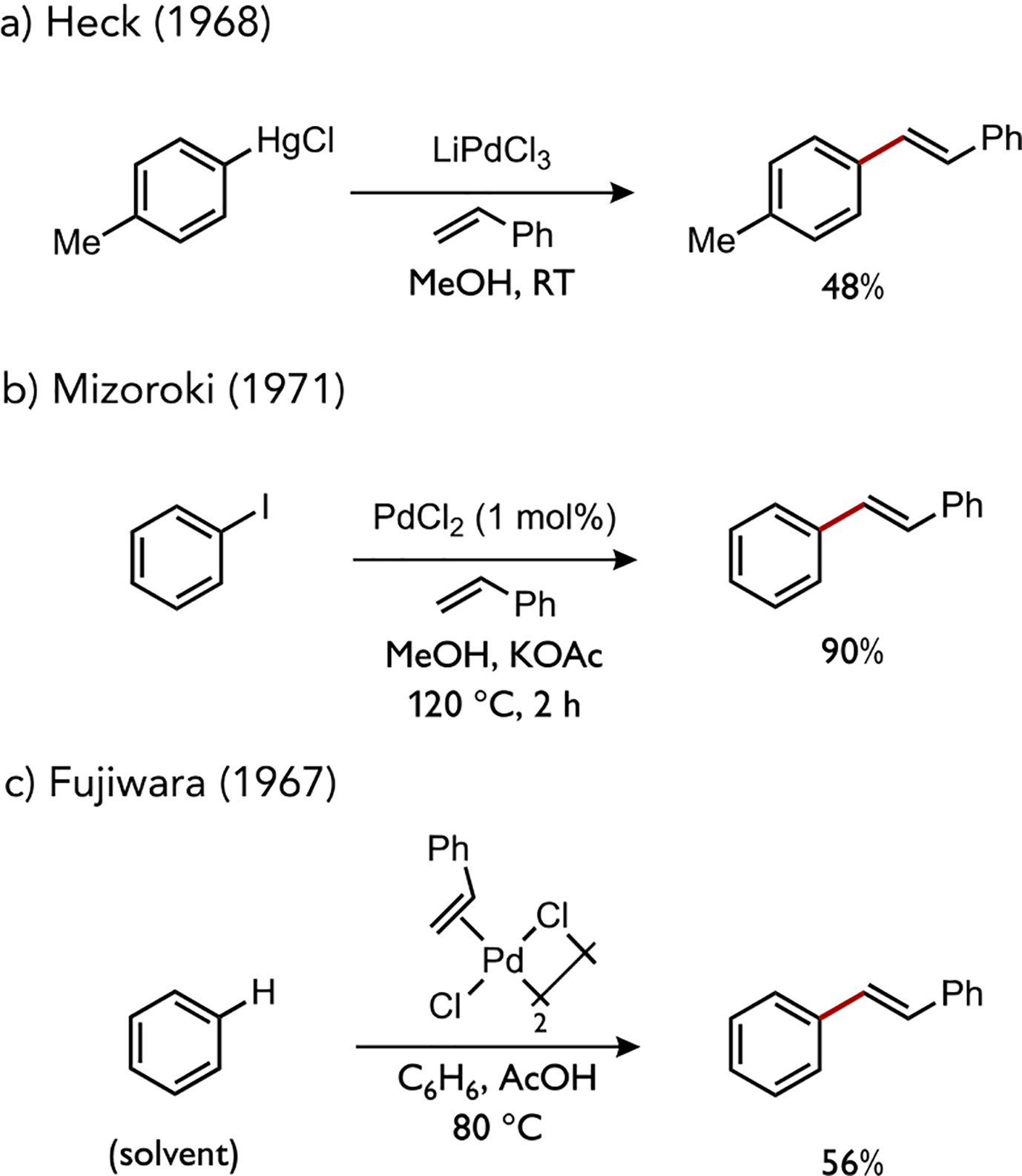

The generation of organotransition metal complexes by cleavage of unactivated C–H bonds is a powerful elementary organometallic reaction featured in a range of modern catalytic processes that form carbon-carbon or carbon-heteroatom bonds.[1] An attractive feature of such C–H activation reactions is the potential to substitute for other elementary catalytic steps that require pre-functionalized substrates, such as transmetalation using organometallic reagents or oxidative addition to (hetero)aryl halides. Several classic cases highlighted in Figure 1 illustrate how the interchangeability of these catalytic steps in unique processes can nevertheless converge to the formation of analogous organic products. Heck demonstrated that alkenylation of arylmercury reagents can be promoted by Pd(II) salts.[2] Shortly thereafter, Mizoroki and Heck independently disclosed that catalytic alkenylation of arylpalladium(II) intermediates could instead be accomplished through a more attractive route initiated by oxidative addition of an aryl iodide to Pd(0).[3]

Figure 1.

Early reports on alkenylation of organopalladium intermediates generated through (a) transmetalation, (b) oxidative addition, or (c) C–H bond cleavage.

At nearly the same time as the development of what would become the Mizoroki-Heck reaction, a more direct route to the same types of alkenyl arene products was developed by Fujiwara and Moritani involving instead the direct metalation of benzene by a styrene-coordinated palladium(II) acetate complex.[4] The acid co-solvent was important in that no reaction was observed in its absence or by substitution for solvents such as acetone, ethanol, or diethyl ether, though chloroacetic acid was also effective.[5] Moreover, Fujiwara found that excess sodium acetate could promote this reaction and the yield of stilbene correlated to the amount of acetate base.[6] The non-innocent role of coordinated carboxylate ligands in catalytic C–H functionalization has been observed in a wide array of processes beyond the Fujiwara-Moritani reaction, and numerous mechanistic studies have established the general potential for a basic ligand to participate in transition metal-promoted C–H bond heterolysis.[7] Catalytic applications featuring this elementary step in catalysis have been comprehensively reviewed.[8]

This review will focus on recent experimental mechanistic studies of base-assisted C–H cleavage and will emphasize how seemingly subtle variations in the transition state can be associated with non-trivial changes in site selectivity. A potentially predictive model has been suggested to associate structural traits of a particular transition metal catalyst with either electrophilic or nucleophilic type reactivity patterns in non-directed C–H functionalization reactions. This structure-reactivity correlation could be useful in the context of a broader goal within this field, which is the realization of predictable and tunable catalyst control of selectivity. Recent evidence supporting the potential mechanisms by which bimetallic cooperativity can influence catalytic C–C and C–X cross-coupling featuring a base-assisted C–H cleavage step will also be discussed, which carries the potential to augment reactivity and selectivity beyond the limitations of any single transition metal complex operating through a monometallic pathway.

2.1. Early Mechanistic Support for Base Assistance During C–H Bond Cleavage

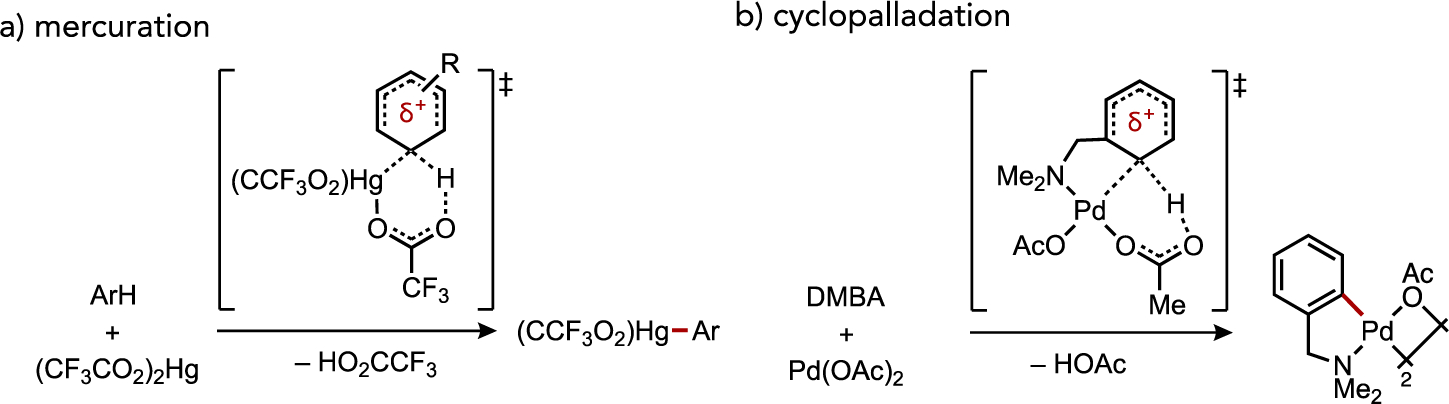

A brief discussion of the origins of base-assisted C–H cleavage mechanistic models is warranted for context relevant to newer studies discussed in subsequent sections below. A more complete discussion of this historical background can be found in several excellent reviews on this subject.[1, 8b, 9] Winstein and Traylor proposed a cyclic, concerted mechanism for protodemetalation of diphenylmercury by acetic acid in 1955,[10] while Roberts later proposed an analogous concerted transition state in the reverse process, mercuration of arenes by Hg(O2CCF3)2 (Figure 2a).[11] Both of these processes feature signatures of electrophilic mechanisms akin to SEAr, but data in subsequent sections will highlight the potential fallacy in assuming electrophilic reactivity is indicative of step-wise SEAr in cases where the pertinent transition metal complex possesses an internal base.

Figure 2.

Similar proposed transition state structures from experimental mechanistic studies on (a) arene murcuration or (b) cyclopalladation of N,N-dimethylbenzylamine (DMBA) by Roberts and Ryabov, respectively.

Returning to early work by Fujiwara on catalytic C–H alkenylation reactions, the pathway(s) by which an arylpalladium(II) species was generated from Pd(OAc)2 and arene was postulated to involve electrophilic attack from arene substituent effects that paralleled Friedel-Crafts chemistry, such as the determination of a negative Hammett ρ value (–1.4).[7, 12] However, a specific mechanism or transition state to understand this Pd-mediated C–H activation step was not explicitly forwarded by Fujiwara at that time. Sokolov later suggested the role for added acetate may extend beyond being the terminal base during cyclopalladation at N,N-dimethylaminomethylferrocene (DMAF). A cyclic transition state was instead proposed involving intramolecular carboxylate assistance.[13] Kinetic analysis by Ryabov of ortho-palladation with substituted N,N-dimethylbenzylamines also pointed toward a highly ordered, polar transition state (Figure 2b) based on observations of a ρ = −1.6, primary kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of kH/kD = 2.2, and a negative entropy of activation (–250 J・K–1).[14] Computational support for such an intramolecular base-assisted concerted mechanism was reported by Sakaki in 2000.[15]

A computational study on the N,N-dimethylbenzylamine (DMBA) cyclopalladation by Davies, Macgregor and co-workers disfavored a potential SEAr pathway through a discrete σ-arenium intermediate.[16] This finding is important because transition metal-catalyzed or mediated C–H functionalizations reactions that favor electron-rich (hetero)arenes are frequently associated with a step-wise SEAr mechanism. The results of DFT analyses nevertheless suggest that concerted mechanisms can also kinetically favor reactions with more π-basic substrates or sites. Thus, Hammett analysis alone may not be a reliable indicator of step-wise versus concerted mechanisms.[17] Ess, Periana, and Goddard later proposed a model, internal electrophilic substitution (IES),[18] to highlight the importance of an electrophilic transition metal center and an internal proton acceptor during C–H cleavage. The term “ambiphilic metal ligand activation” (AMLA) was also coined by Davies and Macgregor to emphasize the important roles of both an electrophilic metal and nucleophilic coordinated base in a concerted C–H bond heterolysis event.[9] Studies of Ru(II)–, Rh(III)–, or Ir(III)–promoted cyclometalations highlight the variety of electrophilic metal complexes possessing a coordinated base (e.g., acetate) that can activate C–H bonds through an analogous concerted mechanism while kinetically favoring π-basic sites, which parallels Friedel-Crafts selectivity.[16, 19]

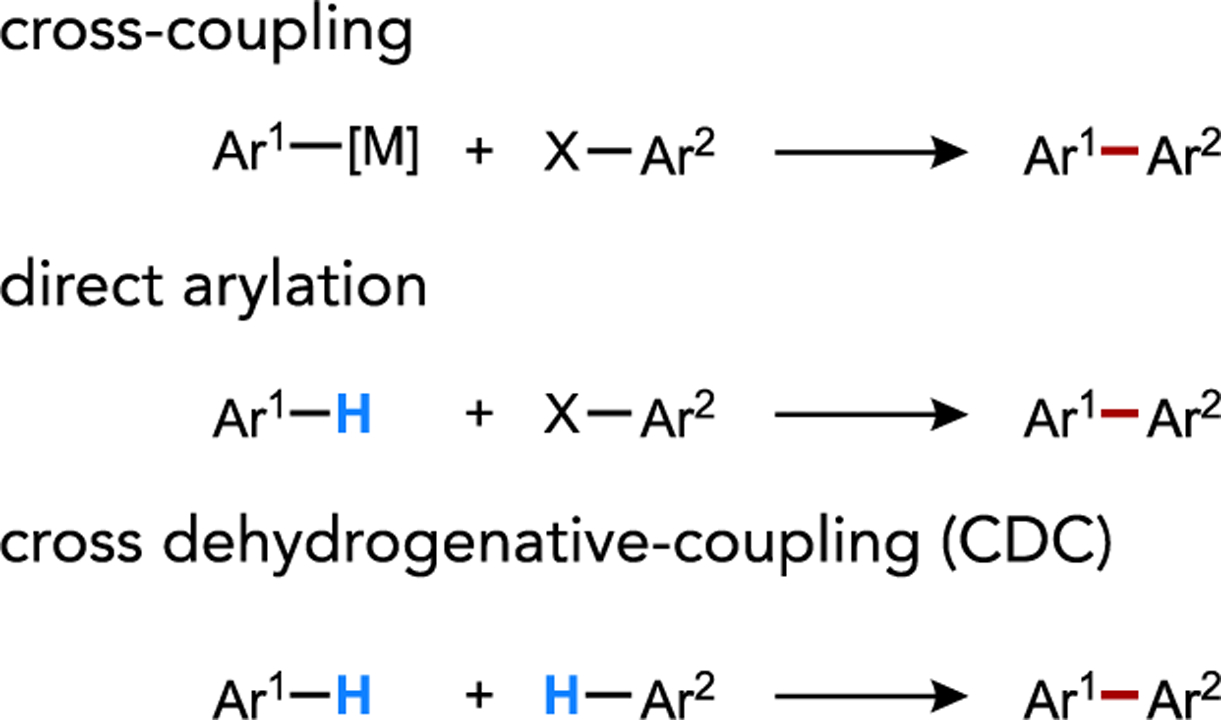

Direct arylation reactions represent an important class of catalytic C–H functionalization reaction where a (hetero)arene substitutes for the typical organometallic reaction partner of a classic cross-coupling reaction (Figure 3). Notably, palladium-catalyzed direct arylation typically strays significantly from the electrophilic selectivity patterns associated with the cyclometalation reactions discussed above. Pioneering mechanistic investigations of Pd-catalyzed direct arylation by Fagnou led to the formalization of a mechanistic model termed “concerted metalation-deprotonation” (CMD), of which a canonical transition state is illustrated in Figure 4.[20] Both the AMLA and CMD models have been widely proposed as typical mechanisms by which C–H activation occurs in direct arylation, Fujiwara-Moritani reactions, and a host of related cross-dehydrogenative coupling (CDC) chemistry involving functionalizations of a broad diversity of C(sp2)–H and C(sp3)–H bonds by distinct classes of transition metal complex possessing some manner of internal base.[8b, 21] The AMLA, CMD and (base-assisted) internal electrophilic substitution (IES or BIES)[18a, 22] models for base-assisted C–H cleavage have often been conflated in the literature, reasonably so given the similarities in the proposed concertedness and transition state connectivity shared among these models. Nevertheless, parsing this general mechanism class into its nuanced variations may nevertheless be informative and of practical value in the context of catalyst design and control of non-directed site selectivity. This will be discussed further in Section 2.5.

Figure 3.

Streamlining C–C cross-coupling reactions by substitution of the organometallic or electrophilic reactant for a transition metal-promoted C–H bond activation step.

Figure 4.

Representative transition state for the concerted metalation-deprotonation (CMD) model formulated by Fagnou.[20b]

2.2. Site Selectivity Trends in Processes Involving AMLA/CMD

Site selectivity in current methods for undirected C–H functionalization,[23] such as C–H borylation,[24] C–H silylation,[25] and the Fujiwara-Moritani reaction (oxidative dehydrogenative Heck reaction), is typically influenced strongly by steric factors. This reactivity pattern can be advantageous in numerous contexts, such as in non-directed C–H borylation or silylation catalyzed by Ir or Rh complexes that provide access to arene substitution patterns complementary to classic SEAr reactions. For instance, mono-substituted benzenes are converted by this chemistry into predominantly meta-disubstituted products while meta-disubstituted benzenes lead to high selectivity for 1,3,5-trisubstituted products. This occurs irrespective of the donating or withdrawing effect of the existing substituents, which provides rapid access to functional group patterns not readily accessible through Friedel-Crafts chemistry. In this regard, the development of Pd-catalyzed direct arylation chemistry is also notable for its departure away from the electrophilic site selectivity associated with earlier examples of C–H metalation reactions, such as mercuration that mirrors SEAr selectivity.[11]

Several important site selectivity trends were identified by Echavarren and Maseras in early mechanistic studies of intramolecular Pd-catalyzed direct arylation reactions.[26] First, functionalization ortho to substituents larger than fluorine was disfavored regardless of their donating or withdrawing capacity, which reflects a sensitivity of the catalyst to the steric environment about the reacting C–H bond. Experimental and computational data also demonstrated a preference for the aryl-Pd(II) carbonate complex to turnover faster by reaction with more acidic C–H bonds, such as those proximal to withdrawing substituents (e.g., F, Cl, NO2).[20a, 27]

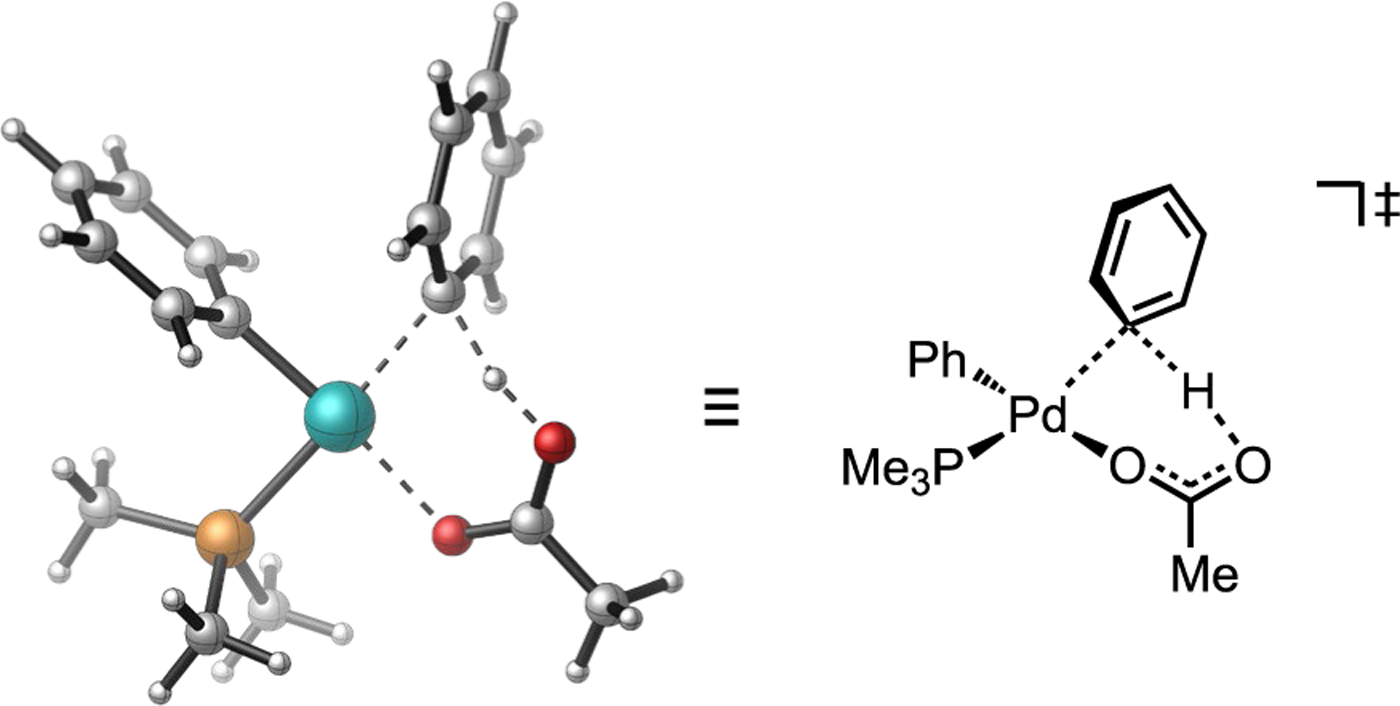

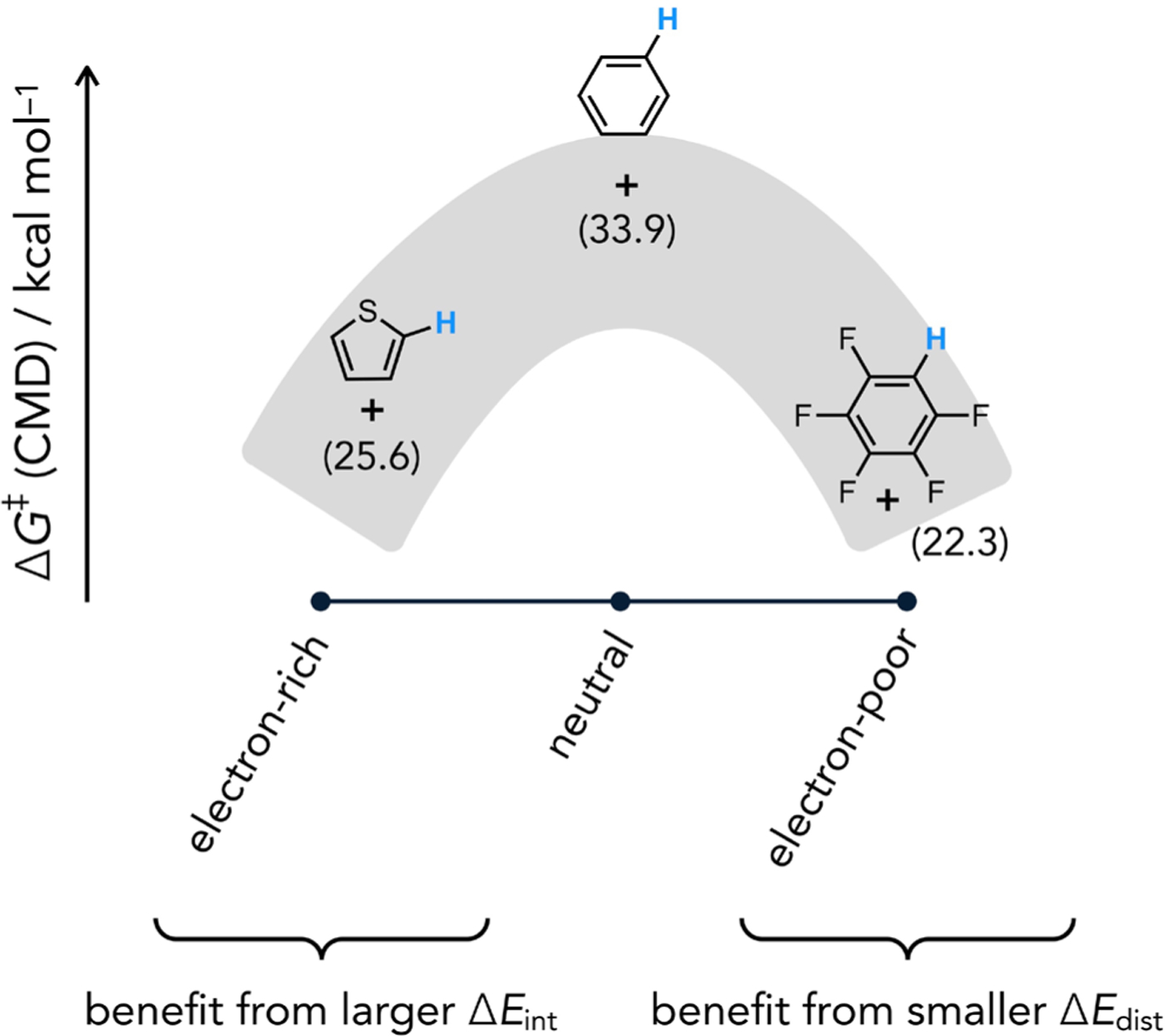

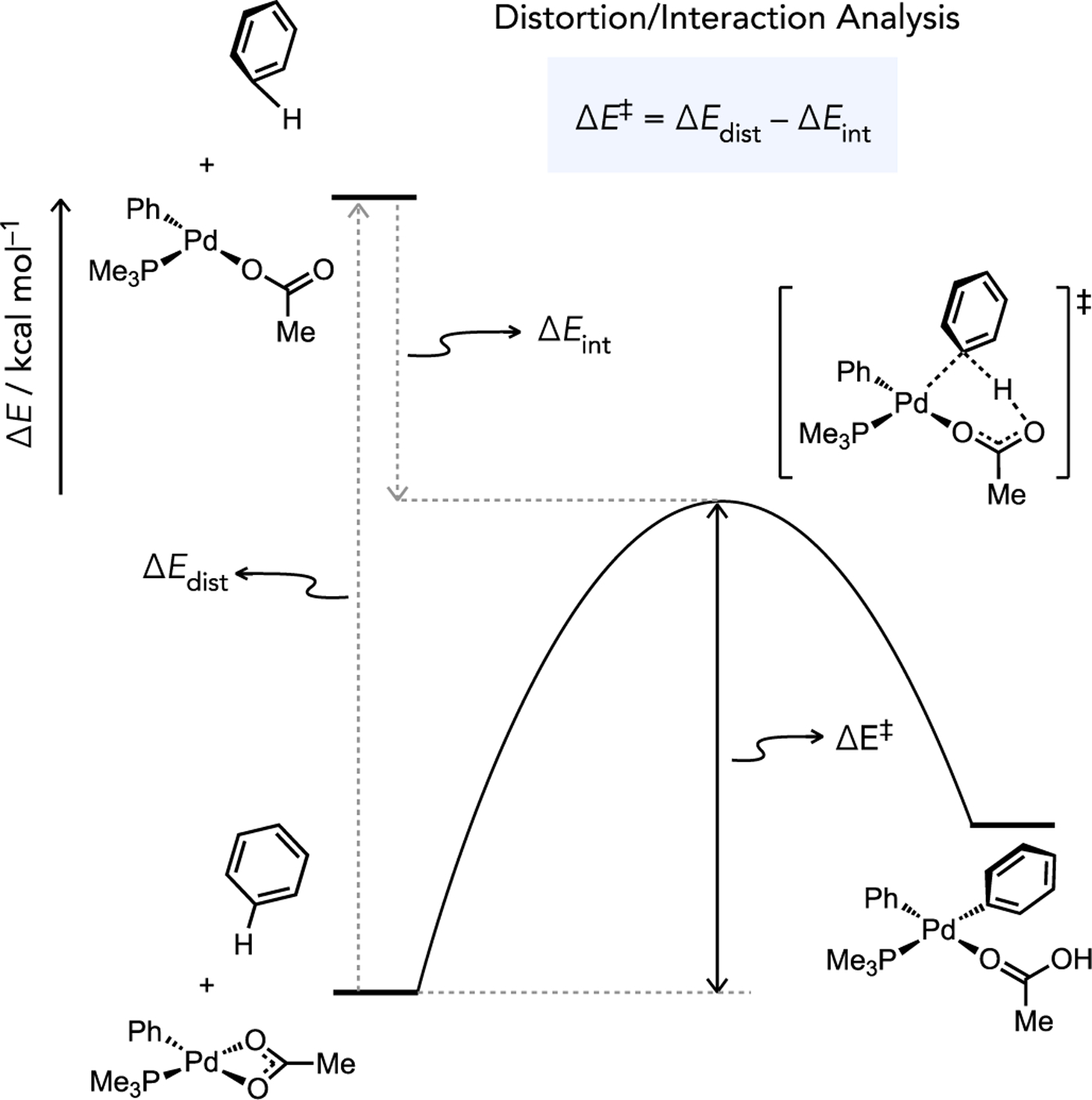

Fagnou and Gorelsky studied the effect of substrate identity on intermolecular direct arylation reactions involving (PMe3)Pd(Ar)OAc intermediates across a wide diversity of (hetero)arene structures and noted several unique reactivity trends. For instance, intermolecular competition experiments and computed CMD energy barriers were used to establish a kinetic selectivity that generally favors more acidic, less hindered C–H bonds. Another notable revelation from these CMD studies was that low energy barriers are predicted for both electron-rich (e.g. thiophene, ΔG‡ = 25.6 kcal/mol at C2) and electron-poor (e.g., C6F5H, ΔG‡ = 22.3 kcal/mol) substrates, the latter of which argues strongly against a mechanism directly analogous to step-wise SEAr pathways. Moreover, simple electron-neutral arenes such as benzene were found to generally be the least reactive (Figure 5) through the CMD pathway (ΔG‡ = 33.9 kcal/mol). A distortion/interaction analysis[28] was used to understand how C–H cleavage can be faster for both electron-rich and electron-poor substrates relative to a simple arene (Figure 6).[20b] From these analyses it became apparent that CMD transition states involving electron-rich substrates typically benefit from higher interaction energies (stabilizing effect), which is intuitive in the capacity of the (hetero)arene to coordinate to an empty site on the transition metal through its π system. On the other hand, the distortion energy required for the substrate to adopt the transition state geometry (destabilizing effect) was found to generally be lower for very electron-poor substrates.

Figure 5.

Representative free energies of activation for CMD between the indicated (hetero)arene and (PMe3)Pd(Ph)OAc.[20b]

Figure 6.

Activation strain analysis of CMD for an arylpalladium intermediate relevant to catalytic direct arylation. Adapted from Ref. [20b].

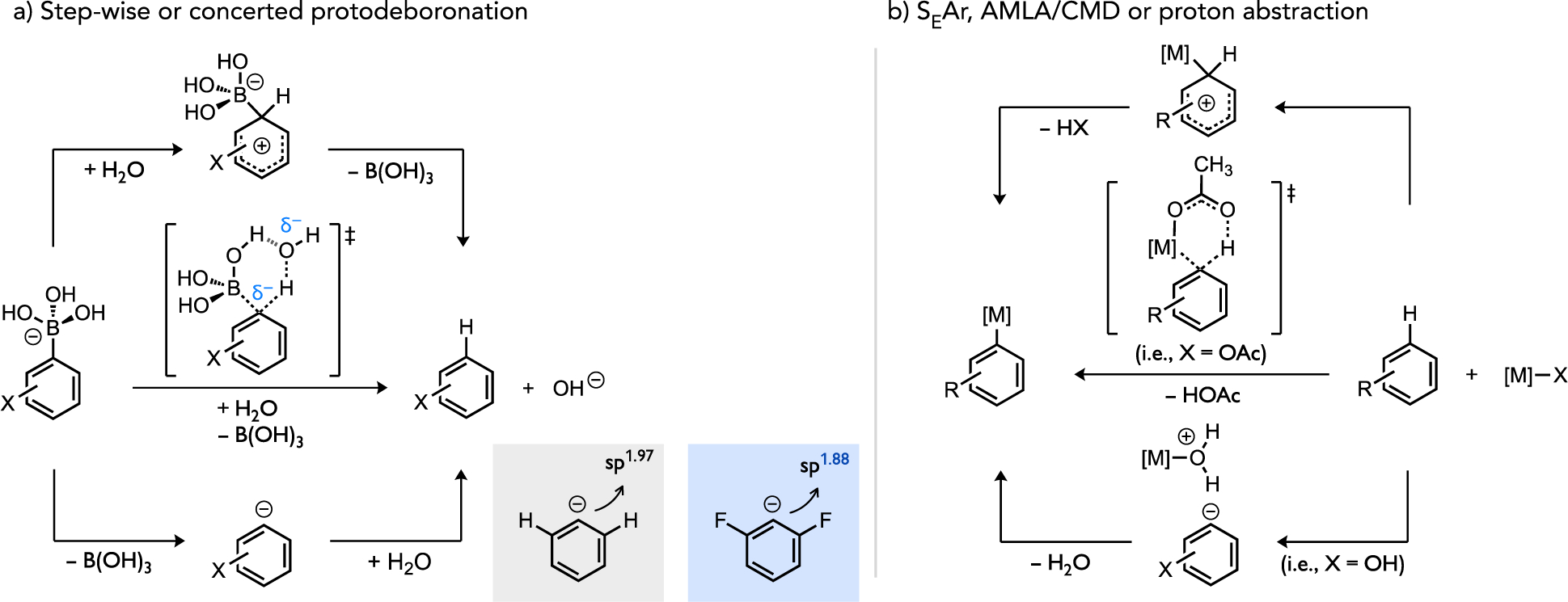

A related effect has been noted in protodemetalation reactions, the reverse process of the above C–H metalation reactions. Particularly for protodeboronation (PDB), Lloyd-Jones elucidated that the rate of PDB of aryltrihydroxyborates possessing di-ortho-fluorination is markedly faster and occurs through a distinct step-wise heterolysis mechanism (Figure 7a, bottom pathway). Analogues lacking such ortho-fluorines instead react through a concerted pathway (Figure 7a, middle pathway), which is mechanistically analogous to CMD.[29] The influence of fluorine substitution on the preferred reaction course was linked to an increase in the s-character of the ipso-carbon that more effectively accommodates build-up of negative charge to the extent that formation of a discrete aryl anion becomes energetically preferable through a step-wise mechanism versus a concerted pathway. Earlier studies of PDB had also postulated an electrophilic substitution mechanism (Figure 7a, top pathway),[30] but direct rate measurements of PDB by Lloyd-Jones found small reaction constants inconsistent with the intermediacy of a σ-arenium complex. It is interesting to note the similarities in the general mechanistic pathways, related through the principle of microscopic reversibility, between protodemetalation reactions of main group organometallic compounds (i.e., arylboronic acids) and potential pathways for C–H cleavage by transition metal complexes (Figure 7b) that are the focus of this review. Specifically, in both reaction classes electron-poor arenes can better accommodate mechanistic pathways necessitating buildup of (partial) negative charge at the rate-limiting transition state or intermediate (i.e., bottom pathways in Figure 7a–b). Consistent with this, the most favorable rates in direct arylation chemistry featuring the CMD mechanism are associated with very electron-poor (hetero)arenes (e.g., C6F5H) and positive reaction constants reflect a propensity to build-up partial negative charge on the substrate during rate-determining C–H cleavage.

Figure 7.

Potential step-wise or concerted mechanistic pathways for (a) a model protodemetalation reaction and for the reverse process (b) C–H metalation.[31]

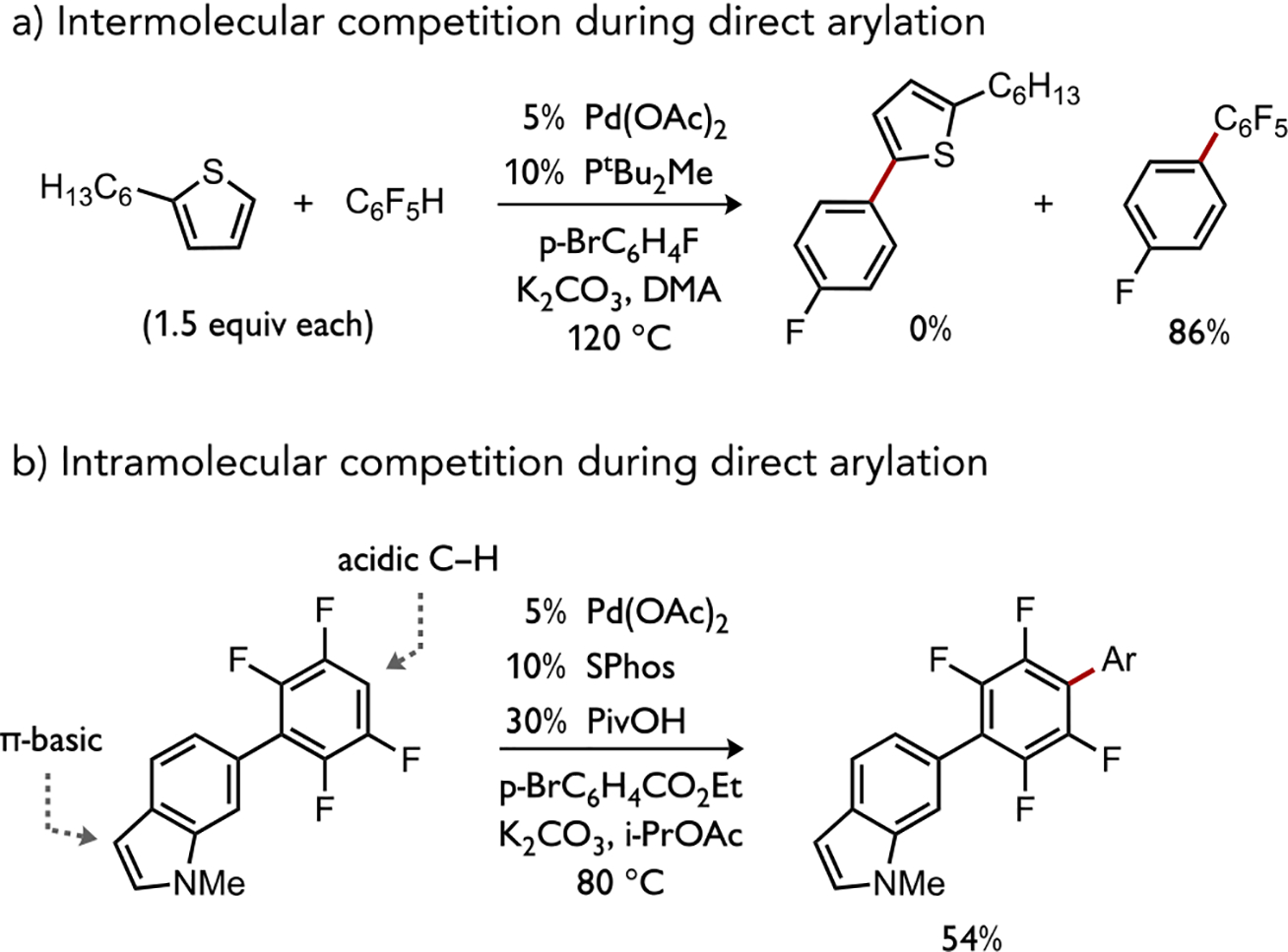

Build-up of partial negative charge in a concerted metalation pathway could mirror the effects observed in protodemetalation reactions; both experiment and computation have predicted that cleavage of C–H bonds during direct arylation can be fastest at sites directly flanked by electronegative atoms.[32] Considering that pentafluorobenzene undergoes CMD with (PMe3)Pd(Ph)(OAc) through a much lower calculated energy barrier than does parent benzene (ΔΔG‡ 11.6 kcal/mol) or does an electron-rich thiophene substrate (ΔΔG‡ 3.3 kcal/mol),[20b, 33] this trend may suggest transition state polarization through charge transfer between catalyst and substrate could be an important kinetic contributor to site selectivity during base-assisted C–H cleavage by a CMD-type mechanism (see Section 2.3). It is thus noteworthy that an intermolecular competition experiment confirmed the high selectivity for direct arylation with C6F5H in the presence of an equimolar amount of thiophene, both present in excess (Figure 8a).[34] Similarly, an intramolecular competition experiment highlights the preference of Pd-catalyzed direct arylation to occur at a more electron-poor site over an electron-rich site (Figure 8b).[35] These computational and experimental results contrast the kinetic selectivity observed, for instance, during cyclometalation reactions by Rh(III) and Ir(III) complexes (vide infra), which favors π-basic sites.[17]

Figure 8.

(a) Inter- and (b) intramolecular competition experiments highlighting kinetic selectivity for an electron-poor over an electron-rich (hetero)arene during Pd-catalyzed direct arylation.[34–35]

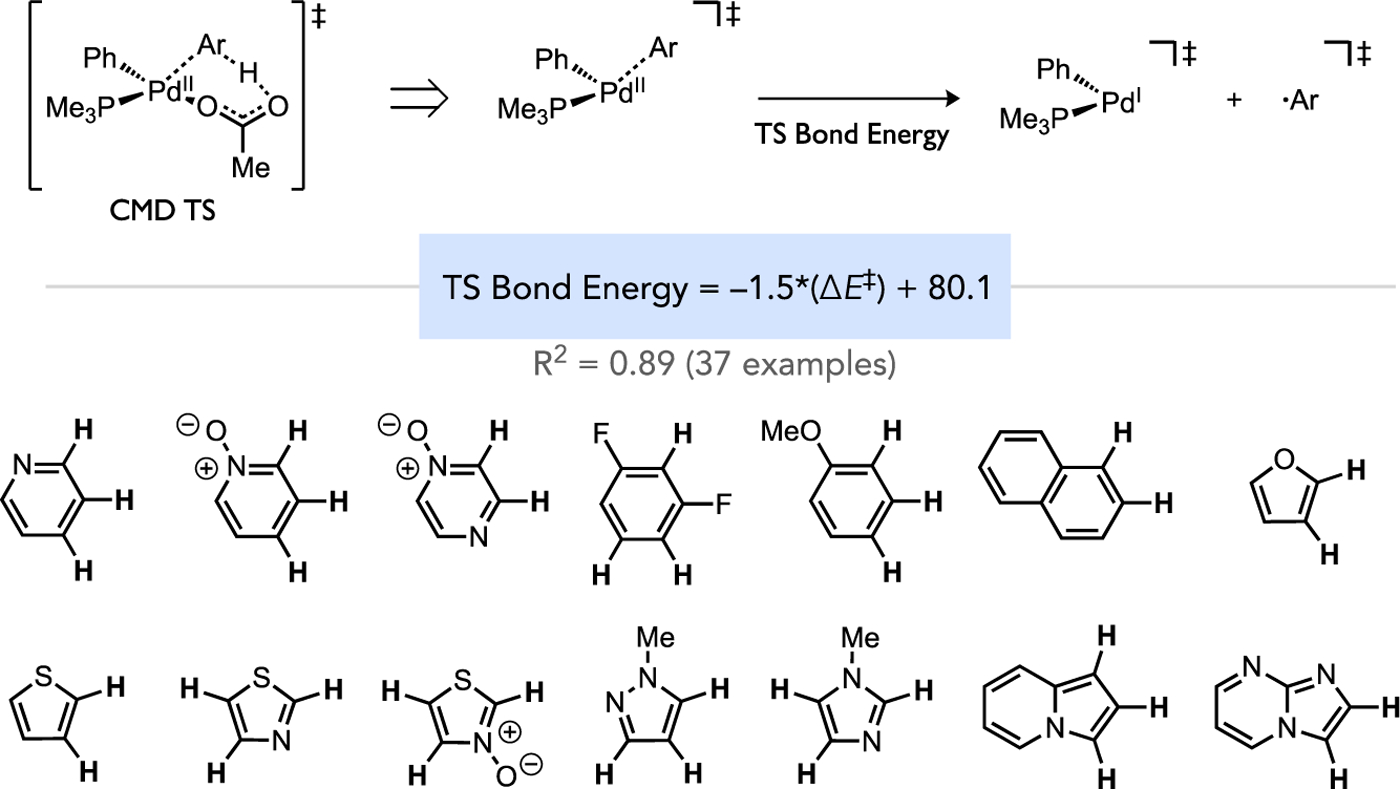

Ess proposed a model to explain the kinetic site selectivity of Pd-catalyzed direct arylation, which parallels the thermodynamic driving force for the reaction.[36] While a general correlation was found between the CMD activation energy and the thermodynamic stability of the resultant organopalladium intermediate, a stronger correlation was found between the calculated energy of the developing Pd–C bond in the CMD transition state (TS) and the overall CMD activation energy. This was determined by computing transition state Pd–C bond energies by first deleting the HOAc fragment from the transition state, then calculating the Pd–C bond energy without geometry relaxation, as illustrated schematically in Figure 9. The linear relationship between the transition state Pd–C bond energy and ΔE‡ for CMD gave a good correlation (R2 = 0.89) from analysis of 37 transition states that vary by the identity of the reacting (hetero)arene. This study thus highlights another contributor to control of site selectivity.

Figure 9.

Computational correlation of the Pd–C bond energy in the CMD transition state versus the overall CMD activation energy to understand the origin of kinetic selectivity during direct arylation.[36]

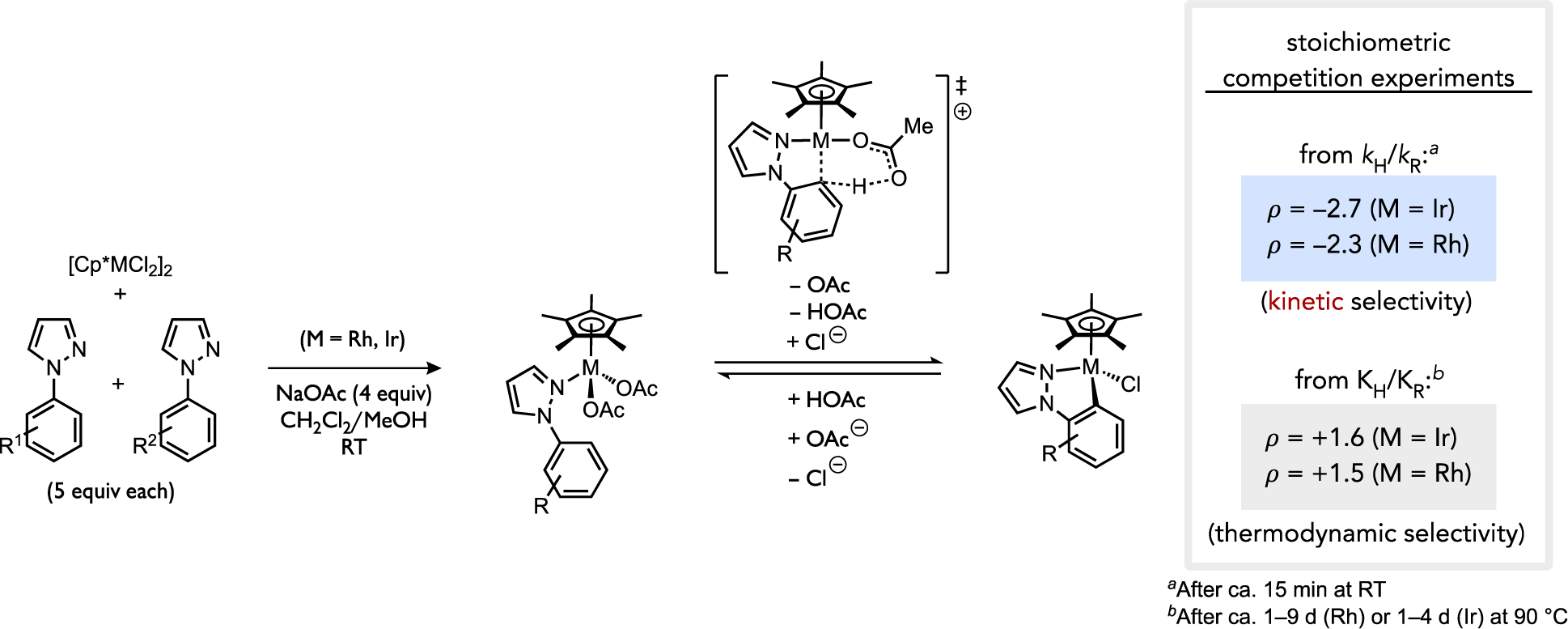

Studies by Fagnou and Gorelsky, along with Ess’s kinetic-thermodynamic selectivity model for direct arylation reactions, have established a kinetic selectivity pattern during CMD reactions that favors sites with more acidic C–H bonds. Under conditions where C–H cleavage is reversible, however, thermodynamic control might also favor reactions with a more electron-poor (hetero)arene or more acidic site due to the formation of a more stable organometallic intermediate (stronger metal-carbon bond). Davies and Macgregor have thoroughly studied cyclometalation reactions of [Cp*RhIIICl2]2 or [Cp*IrCl2]2 complexes in the presence of acetate, species that are proposed to cleave C–H bonds by the base-assisted AMLA mechanism via intermediates of the general form [Cp*M(OAc)(ArH)]+.[9, 17, 19b, 37] At early reaction times (kinetic control) these cyclometalation reactions favor more π-basic sites (Figure 10), which contrasts the kinetic selectivity of direct arylation reactions. This contrasting selectivity is pertinent because the AMLA and CMD mechanisms are often proposed as two descriptors of the same general base-assisted C–H cleavage pathway. The discrepancy in site selectivity for neutral d8 aryl-Pd(II) complexes versus cationic d6 Rh(III) or Ir(III) complexes could be suggestive of non-trivial changes in the C–H cleavage transition states as a function of the reacting metal complex that leads to such changes in substrate or site selectivity. This point will be discussed further in Section 2.5.

Figure 10.

Analysis of selectivity in 1-arylpyrazole cyclometalations under kinetic or thermodynamic control.[17]

The study by Davies and Macgregor on cyclometalation of 1-arylpyrazoles onto Cp*Rh(III) or Cp*Ir(III) complexes also emphasized the importance of validating the rate-determining step in a catalytic process when drawing conclusions about C–H cleavage mechanism from selectivity data.[17] Depending on the substrate identity, it was found that cyclometalation at [Cp*M(OAc)(ArH)]+ (C) can potentially be rate- and selectivity-determining at any of the multiple steps required to traverse the C–H cleavage process by an AMLA pathway (Figure 11). A full reaction analysis for all substrates in the study suggested that a change in hapticity of coordinated acetate (κ2 in B to κ1 in C), leading to an agostic intermediate can be rate-determining, such as when M = Ir and R = 4-NMe2 in the reacting 1-arylpyrazole. On the other hand, loss of acetic acid following C–H cleavage (E to G via intermediate F) was found to incur the highest activation energy in the overall AMLA sequence for M = Rh and R = 2-NMe2.

Figure 11.

Computational results examining elementary steps of stoichiometric cyclometalation reactions involving a Cp*M(κN-1-arylpyrazole)(OAc)2 (A) where M = Rh or Ir. Representative cases are illustrated for different potential rate-determining steps.[17]

After long reaction times (ca. 1–9 d) when the cyclometalation reactions shown in Figure 10 were allowed to reach equilibrium, the preferred metallacycle switched from what was initially observed under kinetic control. The ultimate complex that formed generally correlated to the thermodynamically stronger metal-carbon bond, which appears to be a dominant effect on the equilibration between accessible metallacycle isomers. Together, these observations emphasize that inference of the nature of the C–H heterolysis mechanism in a reaction based on linear free energy relationships or pairwise substrate competition experiments can be potentially problematic if the C–H bond cleavage step is not verified as rate- and selectivity-determining.

With consideration of the above mechanistic models (AMLA, CMD, and IES) that originated from studies of C–H cleavage in distinct transition metal complexes, it is pertinent to consider if these models are in fact supernumerary representations of one general mechanism, as has been postulated.[17, 37] In the context of the broader utility of any one mechanistic model, Goddard, et. al has contended: “[w]hile the definition of precise language regarding mechanisms is worthwhile in its own right, the ultimate utility is whether it provides sufficient insight into the chemistry to suggest improved catalysts.”[18a] In this regard, reconciling how different metal complexes that ostensibly fall under one general model can react with complementary substrate preferences or site selectivity should have practical benefits. For instance, clarifying mechanistic models for guidance in the design of new catalysts that can yield improved selectivity in non-directed C–H functionalizations through a base-assisted C–H bond cleavage pathway remains a desirable endeavor, particularly when applicable to metal catalysts not structurally analogous to species already subjected to deep mechanistic scrutiny. The development of more nuanced subsets of mechanism might be informative in this regard, particularly if systematic structure-mechanism and/or structure-selectivity correlations can be inferred. Consideration of the following questions will guide subsequent discussions in this regard:

How do specific attributes of a metal catalyst (i.e., d-electron count, oxidation state, formal charge, ancillary ligands) influence experimentally-observed site selectivity during base-assisted C–H cleavage?

Is substrate identity more influential than the metal catalyst structure, notwithstanding the presence or absence of an internal base, with regard to selectivity favoring π-basic sites or more acidic C–H bonds?

Are there identifiable, general trends in metal catalyst structure that could be applied toward a priori prediction of non-directed site selectivity that would not require involved calculations of transition states or determination of linear free energy relationships?

Answers to the above questions are relevant to broader goals of advancing catalytic processes featuring C–H functionalization to supplant more traditional, and less sustainable, methods for C–C and C–X bond formation, such as cross-coupling.

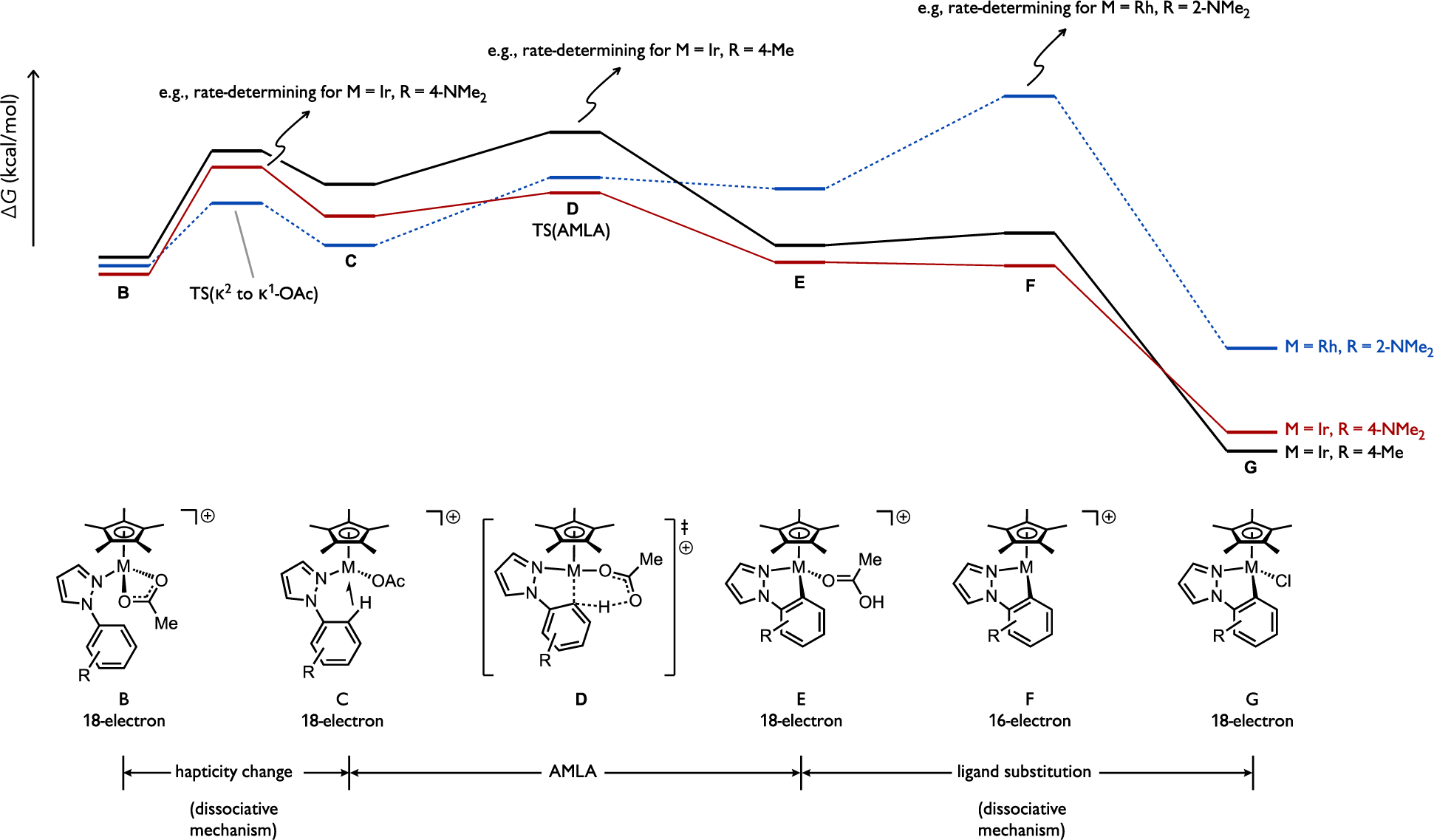

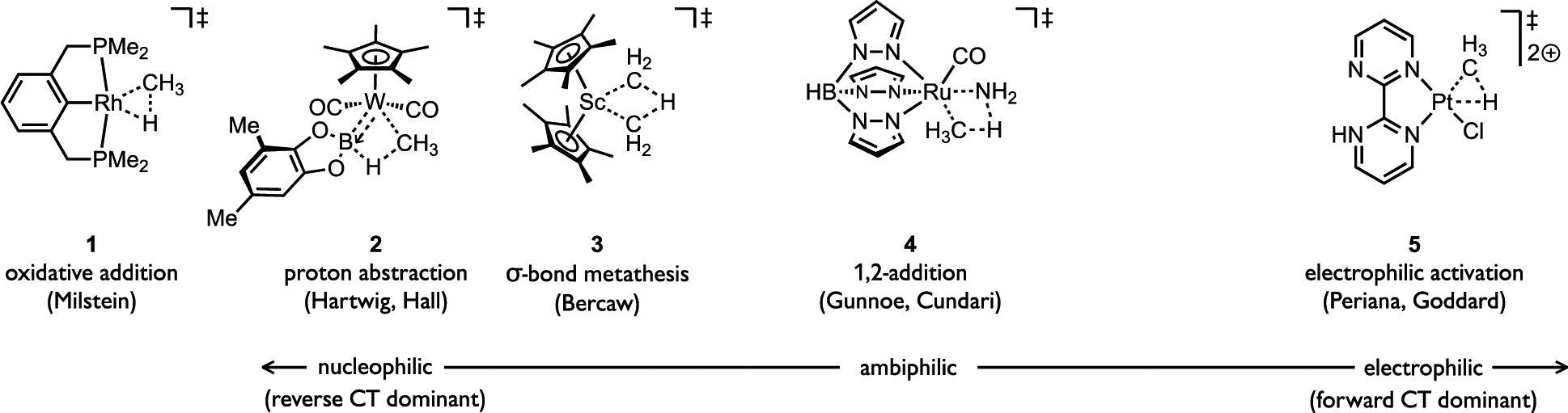

2.3. A Mechanistic Continuum for Base-Assisted C–H Cleavage

The cleavage of (hetero)arene C–H bonds through distinct pathways, such as step-wise SEAr, concerted AMLA/CMD, or proton abstraction mechanisms (see Figure 7b) can be intrinsically linked within a mechanistic continuum that varies by the extent of C–H bond cleavage and M–C bond formation at the rate-limiting transition state. The concept of a mechanistic continuum has previously been proposed in the context of concerted alkane C–H activation mechanisms based on theoretical studies by Ess, Goddard, and Periana. [38] Frontier orbital interactions between the transition metal complex and substrate in the C–H cleavage transition state interactions (Figure 12a) lead to differing extents of forward or reverse charge transfer, and the ensemble of these effects then define where a particular metal complex locates in the continuum. For instance, metal complexes regarded as reacting by oxidative addition (OA) or σ-bond metathesis (σ-BM) mechanisms can be located within a region of the mechanistic continuum defined by greater reverse charge transfer (CT) versus forward CT, as illustrated in Figure 12a. In the case of the low valent d8 Rh(I) pincer complex studied by Milstein (1),[39] the source of electron density is the filled d-orbitals while the d0 Sc(III) alkyl complexes studied by Bercaw (3)[40] derives nucleophilic character from the high ionic character in the M–C bond that interacts with σ*(C–H) of the reacting alkane at the transition state (Figure 13).

Figure 12.

Frontier orbital interactions during responsible for forward and reverse charge transfer relevant to transition state position for (a) alkane C–H activation mechanisms within a charge transfer continuum,[38] and (b) additional frontier interactions contributing to base-assisted C–H activation of (hetero)arenes.[43]

Figure 13.

General illustration of a mechanistic continuum proposed by Ess, Goddard, and Periana defined by the relative contribution of forward and reverse charge transfer (CT) between the reacting metal complex, irrespective of the specific mechanism.[38]

Hybrid mechanisms, such as sigma complex-assisted metathesis (σ-CAM),[41] also locate in this continuum. For instance, reactions between alkanes and a tungsten boryl complex (2) reported by Hartwig and Hall locate in the nucleophilic region of the continuum due to greater reverse CT based on back-bonding from the metal to boron in the C–H cleavage transition state.[42] Complexes with a more balanced contribution of forward and reverse CT reside in the ambiphilic region, such as the (Tp)Ru(II) complex 4. On the other hand, when forward CT becomes dominant, such as for Periana’s Pt(II) dication complex 5, the C–H cleavage transition state locates in the electrophilic region of the continuum. Note that CT interactions are not restricted to the C–H orbitals; so-called syndetic interactions are possible for (hetero)arene substrate through interactions involving π(C–C), or even σ(C–C), orbitals.[43] Another study by Hall used an atoms-in-molecules analysis and also relates a series of different alkane activation mechanisms through the same general transition state by the subtle variations in transition state bonding patterns.[44]

An important consideration in the context of controlling selectivity during C–H activation is that the CT effect on transition state polarization can be enhanced, diminished, or even fully reversed (with respect to catalyst and substrate) depending on the extent of interactions between filled or empty orbitals on the transition metal complex with the complementary orbitals on the reacting substrate. A concept that flows from this idea is that fluctuations in selectivity can be associated with the electronic sensitivity of the transition state. The position of the transition state within the continuum thus suggests what selectivity should be favored, and tuning the polarization could facilitate differentiation between substrates or sites that better “match” a catalyst that favors predominantly forward or reverse CT. The notion of polarity matching is discussed further in Section 2.6.

Gorelsky and Fagnou also postulated the concept of a mechanistic continuum for base-assisted C–H cleavage that included their CMD pathway as one point or region. They wrote: “At one end of this continuum lies a “pure” stepwise SEAr pathway in which the metal–carbon bond is fully formed before the C–H bond cleavage occurs. On the other end would reside a fully concerted process in which the metal–carbon bond is formed at the same time as the C–H bond is cleaved.”[45] In other words, the CMD model as it was originally formulated may not have been intended to comprehensively span an entire mechanistic spectrum of base-assisted transition metal-mediated C–H bond cleavage transition states. The study did, however, indicate that CMD is rather insensitive (i.e. “general”) with respect to the structure of the reacting (hetero)arene, which is consistent with the small reaction constants generally observed in Pd-catalyzed direct arylation. Whether, and to what extent, the identity of the reacting substrate dictates what type of AMLA/CMD or related mechanism (i.e., step-wise SEAr) is favored for other transition metal complexes requires further study.

The potential of the CT continuum concept to help contextualize and classify how certain AMLA/CMD reactions display characteristics of electrophilic or nucleophilic reactivity toward (hetero)arene C–H bonds has to date not been studied in any great detail. Preliminary indications of this possibility were probed by Wang and Carrow through examination of the relative changes in C–H cleavage and M–C formation during concerted, base-assisted (hetero)arene activation across different combinations of transition metal complex and substrate, which was inspired by earlier work by Fagnou.[20b, 45] Such systematic changes could potentially be considered as a mechanistic continuum of base-assisted C–H cleavage pathways that differ by the extent of forward and reverse CT during the concomitant cleavage of a C–H bond and formation of a metal-carbon bond. The relative degree to which either has occurred at the transition state should correlate to the extent of asynchronicity in the concerted mechanism, which should in turn be associated with fluctuations in the magnitude of polarization between catalyst and substrate. Highly polarized transition states would be expected to exhibit a large degree of sensitivity to the electronic properties of the substrate or reacting site, which could be advantageous for the discrimination of one C–H bond among many in a target substrate. On the other hand, minimally polarized transition states may be correlated with a low sensitivity to the substrate electronic properties, which could be advantageous if broad scope is of paramount importance.

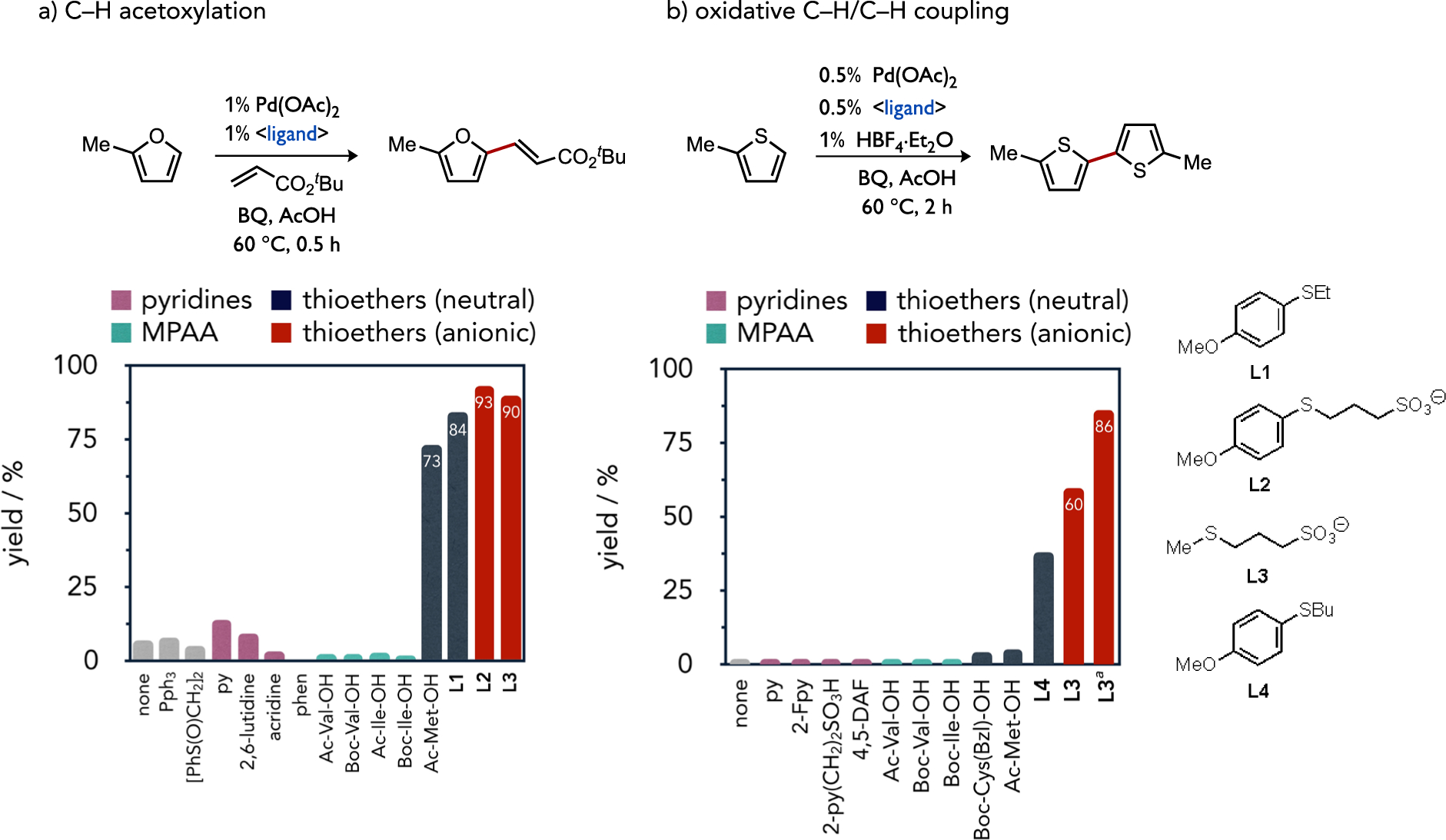

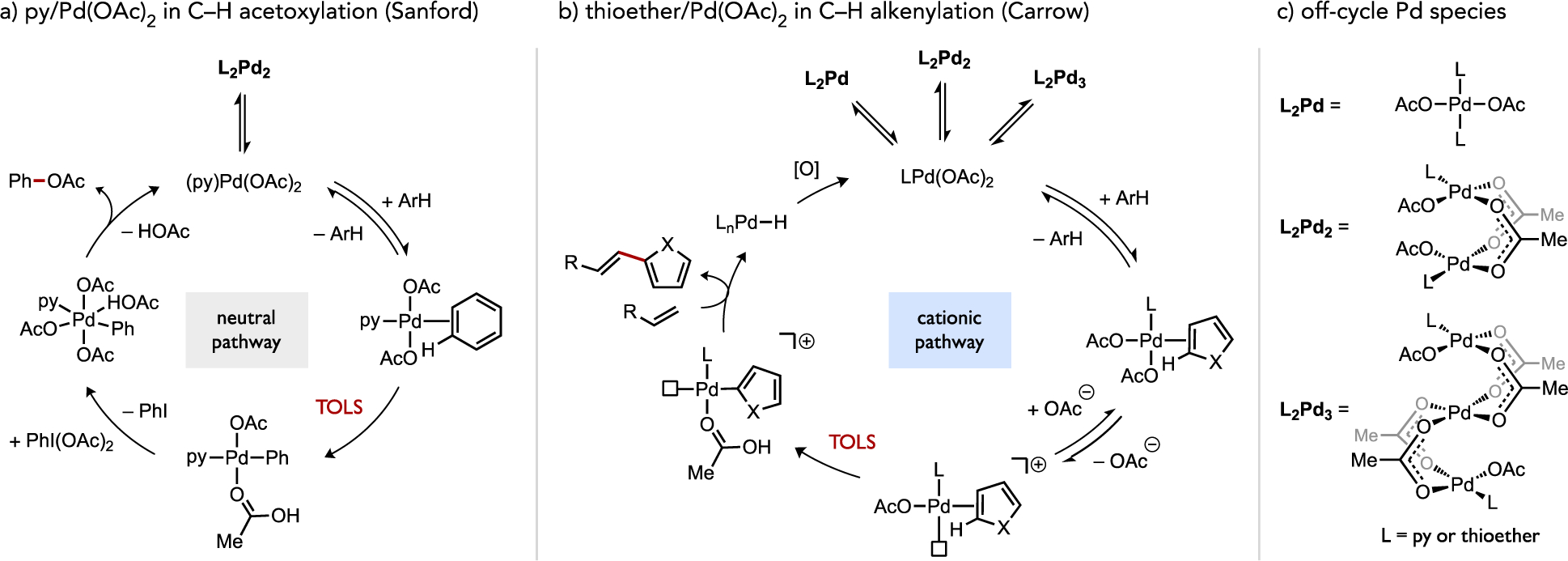

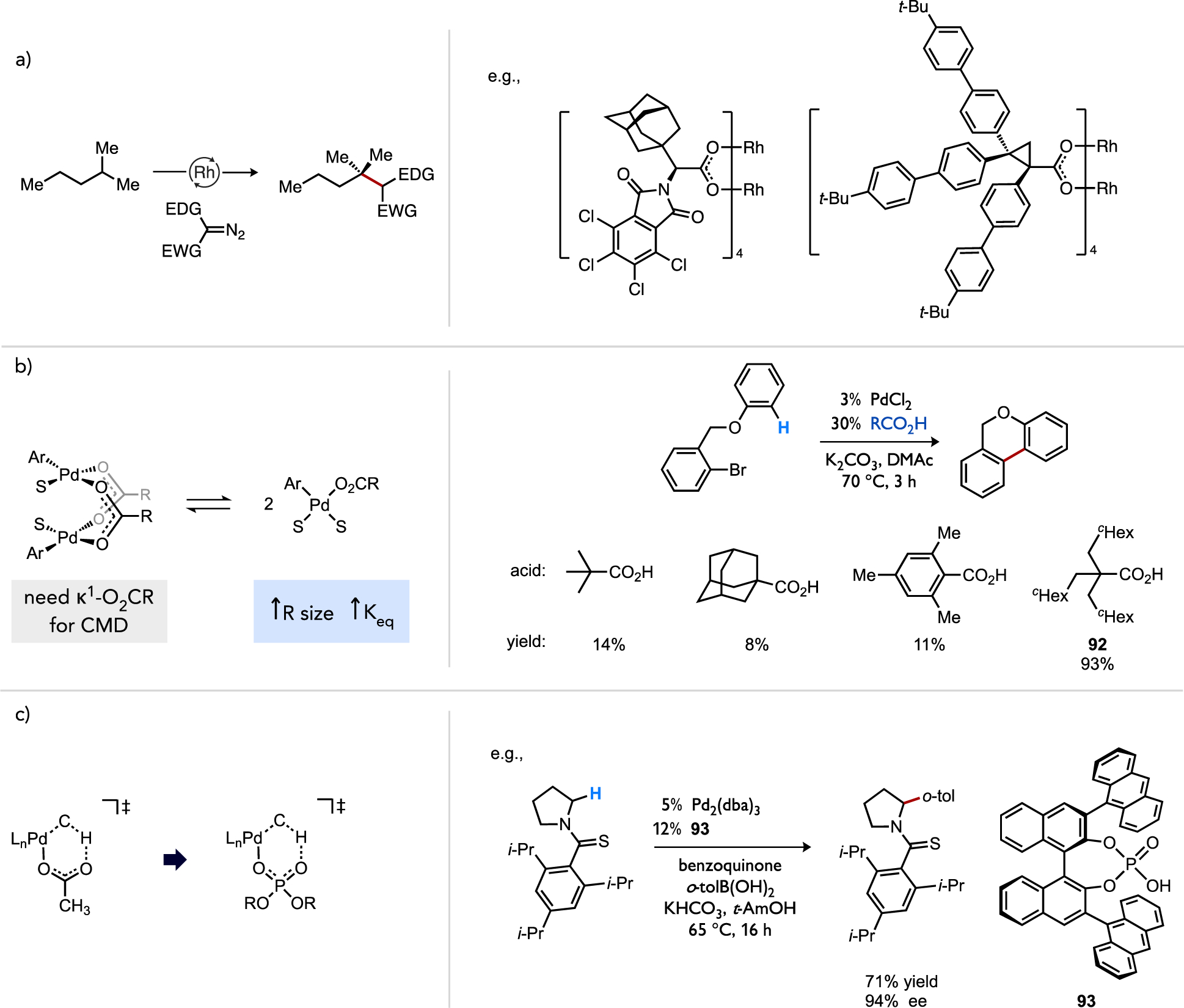

2.4. Electrophilic Thioether-Pd(II) Catalysts

The field of cross-dehydrogenative coupling (CDC) prominently features base-assisted C–H cleavage in one or more catalytic steps.[8d] Catalyst control over the selection of a specific C–H bond for functionalization remains an intense focus of research in both directed and non-directed CDC chemistry, and oxidatively stable ligands are an important tool for enacting control to this end.[46] Pyridine,[47] monoprotected amino acid (MPAA),[48] and 4,5-diazafluorenone (DAF)[49] ligands represent particularly successful examples for oxidative Pd catalysis. Access to other ligand classes remains a need in the field, particularly those leading to new reactivity profiles versus established ligands types.[50] Sulfur-based ligands[51] have relatively recently been demonstrated to markedly accelerate both the Fujiwara-Moritani reaction, also known as the oxidative dehydrogenative Heck reaction (DHR),[4],[7, 52] and C–H/C–H coupling of thiophenes.[53] The impact of ligand choice is evident in screens for ligand-accelerated reactivity in either a model DHR between 2-methylfuran and an acrylate (Figure 14a) or in bithiophene formation by C–H/C–H coupling of 2-methylthiophene (2-MT) shown in Figure 14b.

Figure 14.

Variations in ligand-acceleration during a model dehydrogenative Heck (left) or C–H/C–H coupling to form a bithiophene using common ligand classes developed for oxidative Pd catalysis.[34, 54] aCSA substituted for HBF4, and THF/AcOH used as solvent.

A mechanistic study on the DHR using 4-Me2NC6H4SEt (L1) subsequently uncovered a key mechanistic difference in the structure of the catalyst that promotes C–H cleavage versus mechanisms generally proposed for arene CDC reactions with other Pd catalysts (Figure 15). Conventionally, a neutral pathway for (hetero)arene activation by CMD-type mechanisms is proposed for Pd(OAc)2-catalyzed reactions. Benzene C–H acetoxylation promoted by pyridine-coordinated Pd(OAc)2 represents one such catalytic system studied in detail by Sanford (Figure 15a).[55] When a neutral thioether (e.g., L1) instead coordinates to Pd(OAc)2, kinetic and isotope effect experiments indicated a switch in mechanism wherein ionization of the neutral Pd(II) species occurs reversibly prior to C–H activation. The putative cationic Pd(II) species generated in situ then reacts faster in the turnover-limiting C–H cleavage step with electron-rich heteroarenes (Figure 15b). Cyclometalation involving Cp*MX2 complexes (M = Rh, Ir; X = Cl or OAc) has also been proposed in separate studies by Davies and Macgregor and Jones to proceed by initial ionization to a generate a more reactive cationic species, such as [Cp*M(OAc)]+, prior to C–H bond cleavage.[19, 56] Complexes such as these are all associated with electrophilic reactivity patterns through a concerted mechanism for C–H cleavage. This formal charge difference between neutral and cationic pathways for C–H bond cleavage (i.e., during the catalytic oxidative DHR) also bears analogy to the distinct substrate preferences and selectivity patterns associated with the Mizoroki-Heck reaction operating through either a neutral or cationic catalytic pathway.[57]

Figure 15.

Proposed catalytic mechanisms through (a) a neutral pathway for benzene C–H acetoxylation using pyridine-coordinated Pd(OAc)2 or (b) a cation pathway for heteroarene C–H alkenylation using thioether-coordinated Pd(OAc)2.[54–55] (c) Off-cycle catalytic intermediates identified in these studies are also noted.

The mechanistic pictures for ligand effects on catalysis are complicated by the formation of multi-metallic species, which have been separately identified by Sanford and Carrow through ligand titration experiments and internally-calibrated DOSY NMR molecular weight determination (Figure 15c).[54–55] It was concluded that these aggregates are off-cycle species during C–H acetoxylation or alkenylation reactions, respectively, but the existence of such species begs the question of whether, under other circumstances, multi-metallic pathways could be more reactive or selective than monometallic analogues during AMLA/CMD-type catalytic C–H functionalization (see Section 2.6).

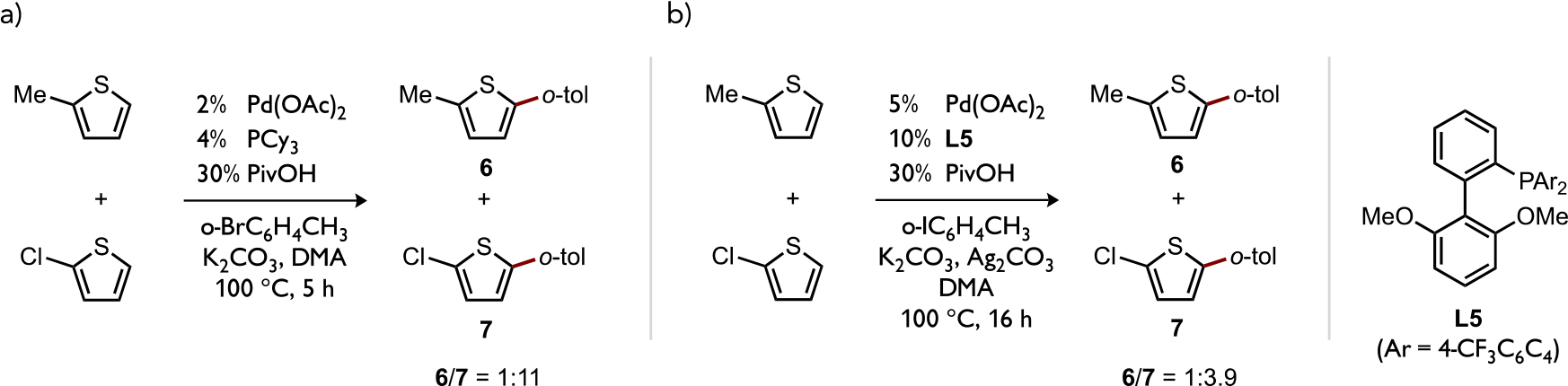

The potential consequences of ligand-enhanced effects on reactivity patterns or selectivity during Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalizations are also pertinent. For instance, Fagnou had shown the preference for a (PR3)Pd(Ar)OAc (PR3 = PCy3 or L5) intermediate to competitively react by CMD with a 2-substituted thiophene possessing the more acidic C–H bond (6/7 = 1:3–1:11; Figure 16a). This corresponds to formation of a more thermodynamically stable Pd–C bond as noted previously,[36] and this was verified to occur under kinetic control at the C–H cleavage step both by calculated differences between the two possible CMD energy barriers and the experimental KIE of kH/kD = 5.6 from independent rates measurements using benzothiophene or 2-d-benzothiophene and the catalyst shown in Figure 16b.[27a, 58]

Figure 16.

Selectivity of Pd-catalyzed direct arylation in competition experiments between a more or less electron-rich thiophene under two different sets of reaction conditions.[27a, 58]

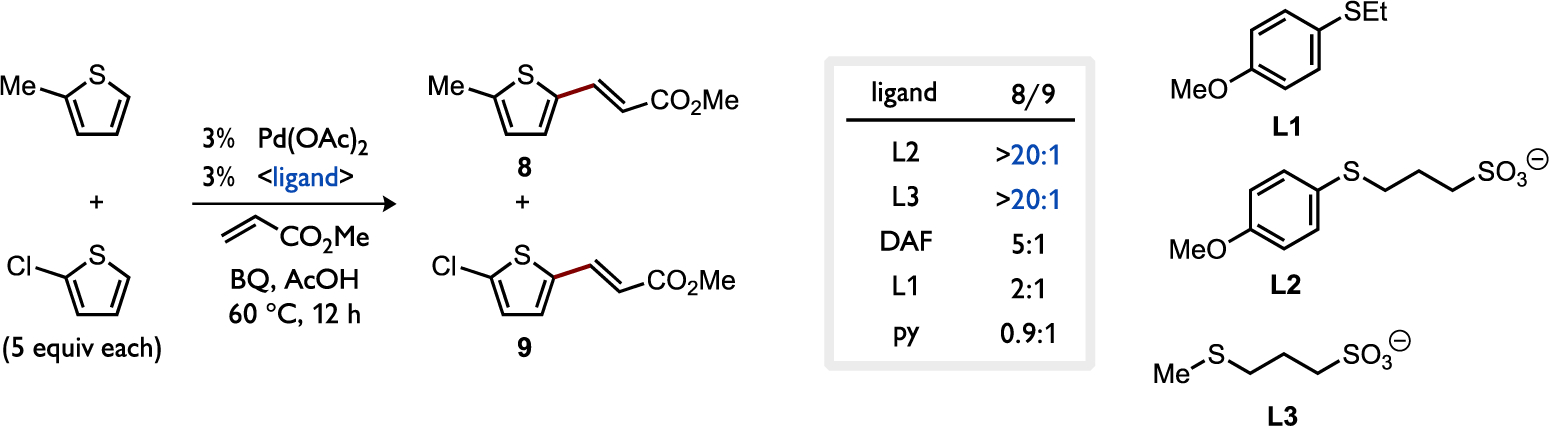

On the other hand, the substrate preference generally changes to favor the more electron-rich 2-methylthiophene in a competition experiment involving C–H alkenylation (DHR) as shown in Figure 17. While pyridine-coordinated Pd(OAc)2 shows little preference between either substrate (8/9 = 0.9:1), substitution for other ligands generally enhances the catalyst preference for the more electron-rich substrate (8/9 = 2:1 to >20:1). The highest selectivity was observed for Pd catalysts coordinated by anionic thioethers L2 or L3, which are particularly reactive toward C–H alkenylation with electron-rich heteroarenes.[54] This switch in substrate preference could be indicative of a change in the nature of the transition state of C–H cleavage; while tempting to attribute the electrophilic reactivity in the C–H alkenylation reactions to a step-wise SEAr type pathway, it was shown for the thioether-Pd cases that C–H cleavage is turnover-limiting. It should be noted that the turnover-limiting step of C–H alkenylation has not been established for cases employing pyridine- or DAF-coordinated Pd(OAc)2. Thus, differences in observed selectivity could potentially originate from different selectivity-determining steps as the ligand identity is varied.

Figure 17.

Ligand effect on competitive C–H alkenylation between a more or less electron-rich thiophene under otherwise identical reaction conditions.[54]

2.5. Electrophilic Concerted Metalation-Deprotonation (eCMD)

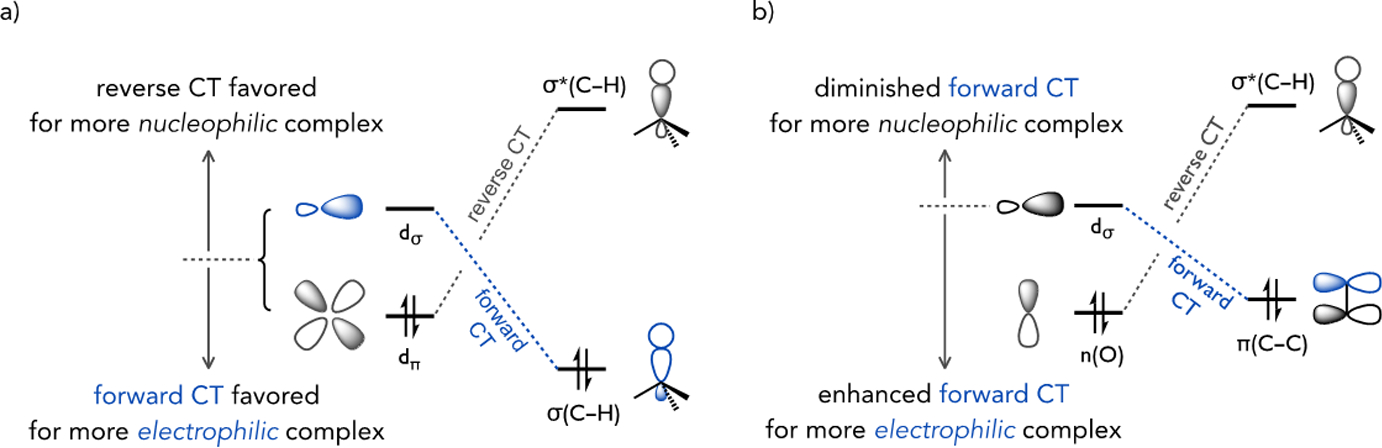

There are today a significant number of examples of transition metal catalysts that promote base-assisted C–H bond cleavage in (hetero)arenes and also display electrophilic reactivity patterns that mirror SEAr reactions. In such cases where C–H cleavage has been shown rate-determining, and thus selectivity determining, the electrophilic reactivity pattern originates from the nature of the AMLA/CMD transition state. While the AMLA and CMD models share a number of similarities, particularly in the general constitution of atoms in the C–H cleavage transition state, the former model originated from studies of complexes exhibiting electrophilic reactivity patterns while the latter did not. The direct arylation reactions studied by Fagnou to develop the CMD model were shown to occur through rate-limiting C–H cleavage, in most cases, yet the site selectivity for these reactions routinely strays from SEAr type reactivity patterns favoring instead more electron-poor (hetero)arenes or sites with more acidic C–H bonds.[20b, 36, 45] Contrasting kinetically-controlled site selectivity patterns in the reactions around which these two models were developed leaves open the question about where then the selectivity differences originate.

The computed Hammett parameters for functionalization of 2-subsituted thiophenes during direct arylation reactions (ρ = +1.3)[20b] versus C–H/C–H coupling reactions catalyzed by a (κ2S,O-L3)Pd(OAc) species 10 (ρ = −7.1)[34] highlights that even complexes based on the same metal and oxidation state, Pd(II), exhibit dramatic differences. The change in sign of these linear free energy relationships is suggestive of a reversal in the direction of polarization between catalyst and substrate at the C–H cleavage transition state, with the presumably more electrophilic (κ2S,O-L3)Pd(OAc) 10 species accepting more electron density from the substrate than does the relatively electron-rich organometallic species (PMe3)Pd(Ar)(OAc) 11.

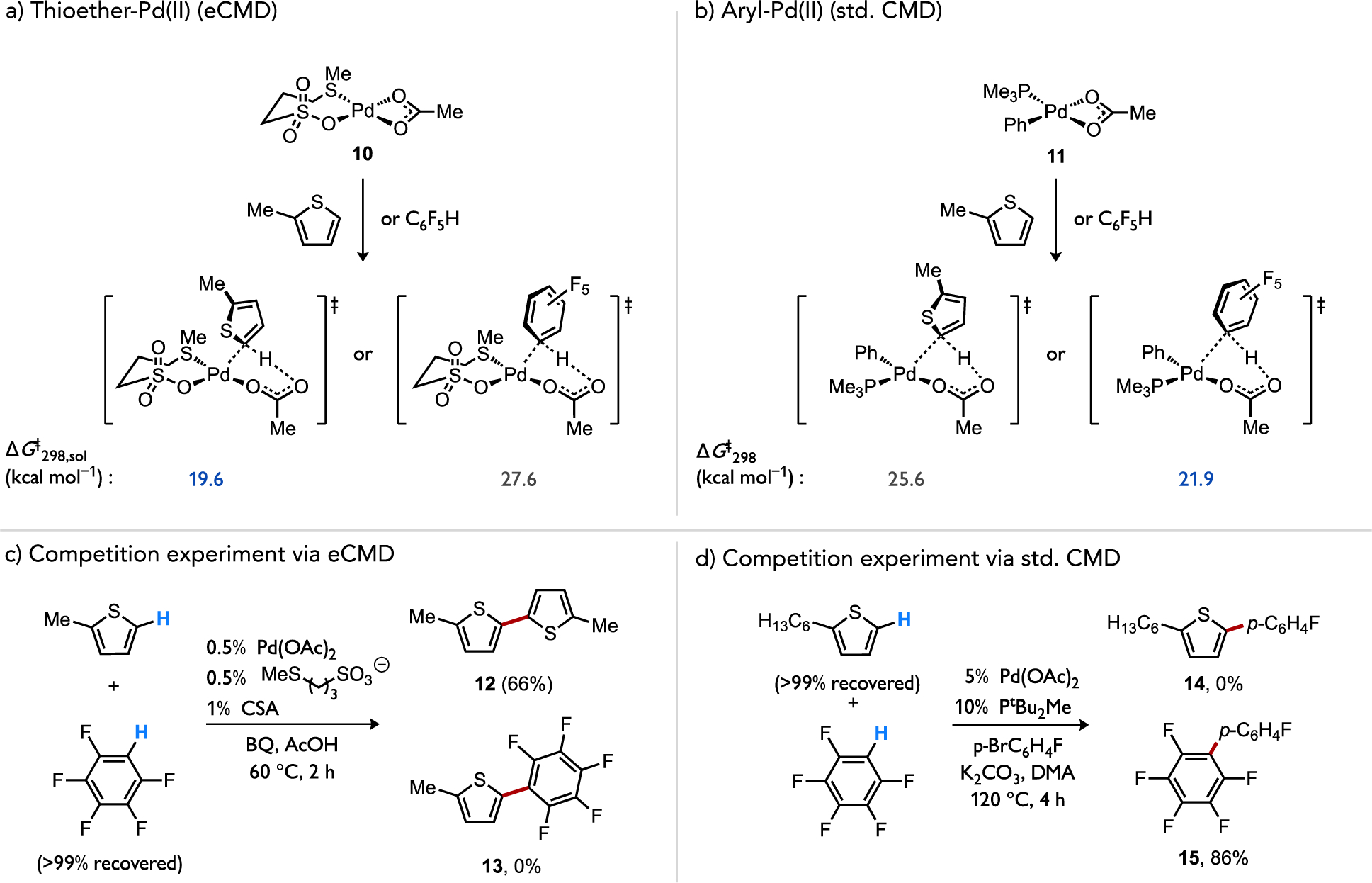

Calculations of the relative activation energies for (κ2S,O-L3)Pd(OAc) 10 to cleave the C–H bond in an electron-poor (C6F5H) versus an electron-rich (2-MT) (hetero)arene strongly favors the latter by ΔΔG‡ = 8.0 kcal/mol (Figure 18a).[34] This parallels the electrophilic reactivity noted in studies of base-assisted C–H cleavage reactions, such as in arene mercuration, DMBA cyclopalladation, and cyclometallations at Cp*Ir(III) or Cp*Rh(III) complexes discussed above. On the other hand, the relative activation energy for C–H cleavage of the same two substrates by an arylpalladium complex (PMe3)Pd(Ph)(OAc) 11 involved in direct arylation chemistry also exhibits a biased preference but favors the opposite substrate, the electron-poor arene by ΔΔG‡ = 3.7 kcal/mol (Figure 18b). When competitive catalytic experiments were conducted with these two substrates, the C–H/C–H coupling using L3/Pd(OAc)2 as catalyst gave a perfect selectivity for biaryl formation through C–H cleavage at 2-MT to form product 12 over C6F5H to form product 13 (Figure 18c) in agreement with the respective calculations. In contrast, direct arylation gave exclusive biaryl formation corresponding to C–H cleavage at C6F5H to form product 15 over 2-MT to form product 14 (Figure 18d) that also agrees with the respective calculations. It should be noted that recent calculations of Ag(I) carboxylates have also found a strong preference for C–H cleavage at a more electron-poor arene (Figure 19) that mirrors Pd-catalyzed direct arylation. From these observations it is apparent that the structure of the reacting metal complex is directly implicated in the ability to switch the electronic preference of a C–H functionalization reaction featuring a base-assisted mechanism.

Figure 18.

Calculated activation energies for C–H cleavage in an electron-poor (C6F5H) or electron-rich (2-MT) substrate by (a) an electrophilic Pd(II) complex or (b) a less electrophilic organo-Pd(II) complex. Correlation of the calculated selectivity to catalytic (c) C–H/C–H coupling or (d) direct arylation reactions featuring the same catalytic intermediates.[34]

Figure 19.

Calculated CMD transition states for a Ag(I) acetate complex favor reaction with the more electron-poor (hetero)arene, in analogy to reactivity trends in Pd-catalyzed direct arylation.[59]

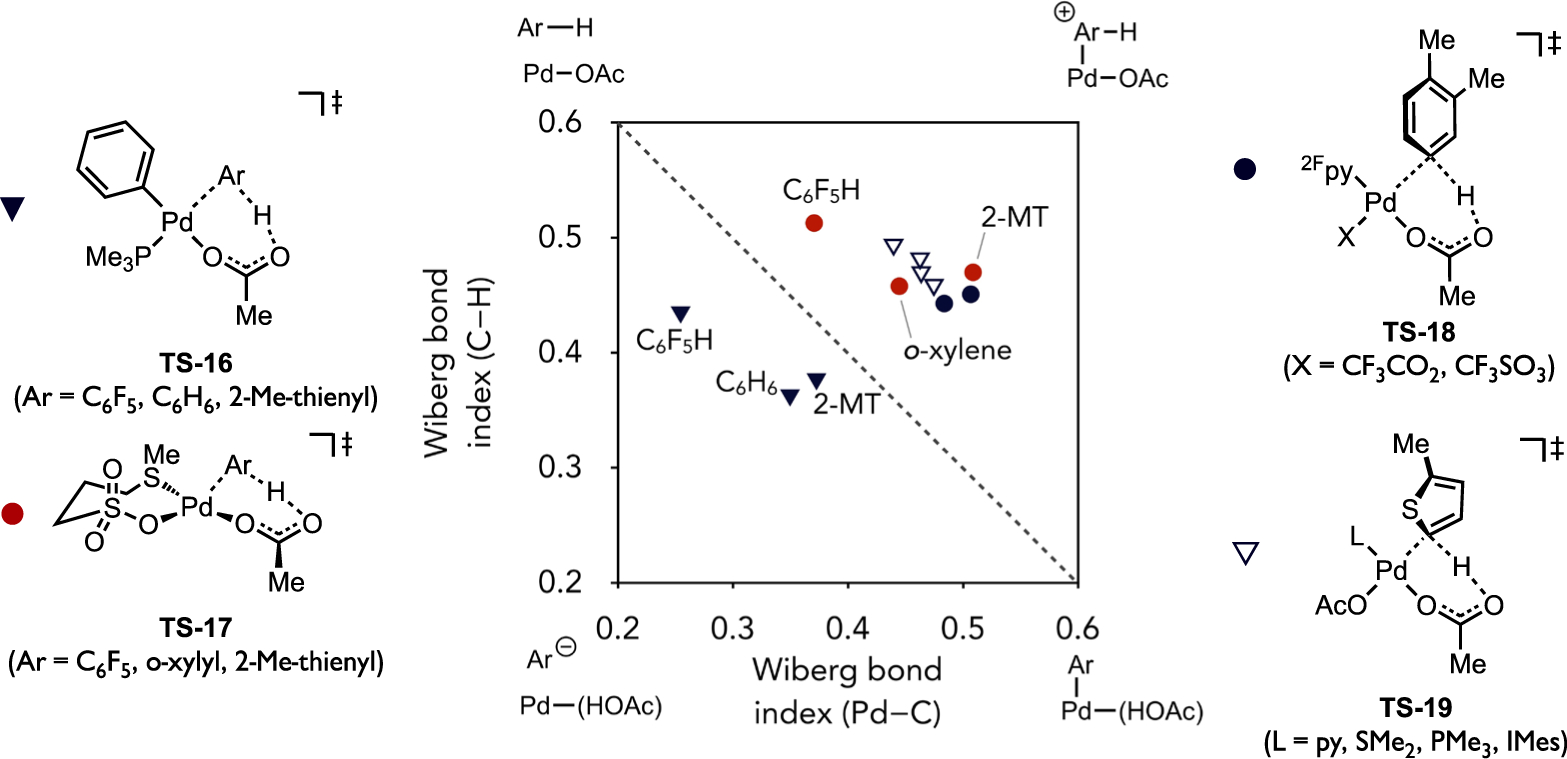

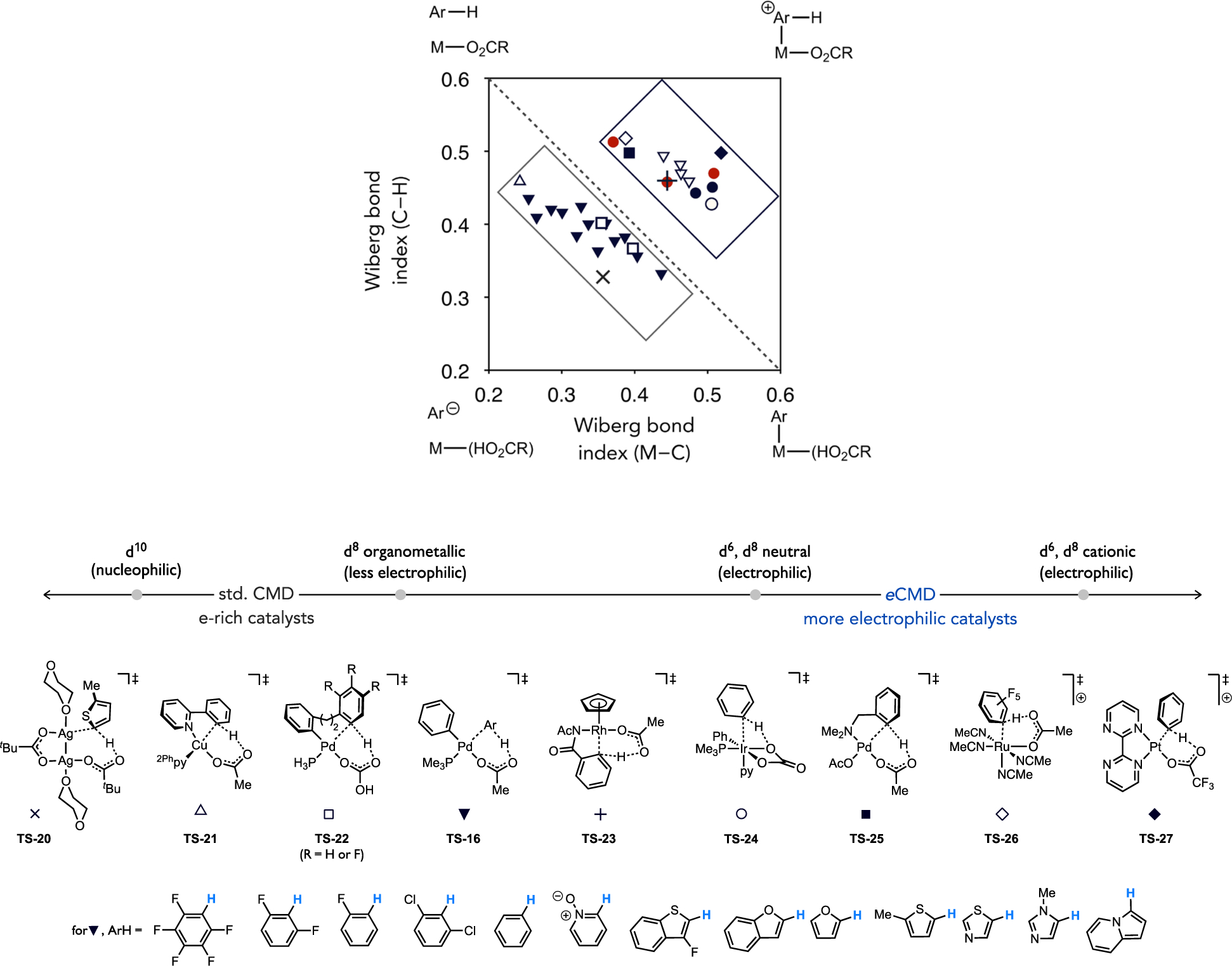

Differences in transition state polarization between different Pd(II) species can be visualized in a More O’Ferrall–Jencks (MOFJ) plot[60] (Figure 20) for representative cases involving C–H cleavage in an electron-rich, neutral, or electron-poor (hetero)arene.[34] The Wiberg bond indices were determined, in some cases, from DFT-optimized transition states derived from different functional and basis sets, yet a qualitative analysis of these data can still be informative. The reaction coordinate for this MOFJ plot flows from top-left to bottom-right with the dashed line nominally representing a synchronous process. Trajectories that deviate from the diagonal remain concerted but become increasingly asynchronous upon greater displacement of the transition state perpendicular to the diagonal. Step-wise pathways are represented by the far corners of the plot. Formation of a σ-arenium intermediate would occur with complete M–C bond formation before appreciable C–H bond cleavage. On the other hand, C–H cleavage that is significantly more advanced than M–C bond formation represents a proton abstraction pathway. Transition states locating near these canonical extremes would be expected to have intermediate levels of charge build-up on the ipso carbon, partial positive charge above the diagonal and partial negative charge below.

Figure 20.

More O’Ferrall–Jencks plot featuring several representative organometallic or inorganic Pd(II) complexes activating the C–H bond in a canonical electron-poor, neutral, or electron-rich substrate.

The transition states involving the direct arylation intermediate (PMe3)Pd(Ph)(OAc) (TS-16) with the three model (hetero)arene substrates each locate below the diagonal, in agreement with the generally modest, positive reaction constants reported for direct arylation upon variation of the substrate electronic properties. In contrast, the activation of the same three substrates by (κ2S,O-L3)Pd(OAc) (10) each locate above the diagonal and are indicative of a build-up of partial positive charge on the ipso carbon at the transition state. The transition state corresponding to activation of 2-MT is the most displaced from the synchronous diagonal and thus the most asynchronous reaction. It is suggested from these data that the thioether-coordinated complex is particularly electrophilic among Pd(II) complexes associated with base-assisted C–H cleavage. Another electrophilic Pd(II) catalyst developed by Stahl, (2Fpy)Pd(OAc)(OTf) (2Fpy = 2-fluoropyridine) formed by the combination of Pd(OAc)2 and Cu(OTf)2 or Fe(OTf)3, was found to react through transition states TS-18 that also locate in this region of the MOFJ plot.[61] The Pd complexes noted above that act either as electrophilic catalysts, such as complex 10 or (2Fpy)Pd(OAc)(OTf), versus more nucleophilic catalysts, such as (PMe3)Pd(Ar)(OAc) (e.g., 11) species in direct arylation, exist in the same oxidation state (+2) and feature the same internal base (acetate). The only differences in their structure that can account for this differing reactivity in otherwise similar six-membered C–H cleavage transition states is the identity of their spectator ligands.

It stands to reason that the ligand identity may then be the origin of the differences in polarization between catalyst and substrate, which is otherwise weakly affected by the (hetero)arene identity. Either the L-type and X-type ancillary ligand, or both, might be important in this regard. To gain some preliminary insight to this end, transition states (TS-19) and Wiberg bond indices were calculated for activation of 2-MT by a series of LPd(OAc)2 complexes that only vary in the dative (L-type) ligand identity (L = py, SMe2, PMe3, or 1,3-dimesitylimidazol-2-ylidene (IMes)) that span a range of σ-donicity. These tightly cluster in the MOFJ plot suggesting the polarization of the transition state is weakly affected by the dative ligand for reactions involving d8, Pd(II) complexes. It was postulated then that the X-type ligand exerts greater influence. In particular, hydrocarbyl ligands possessing one of the largest trans influence in the spectrochemical series could diminish the electrophilicity of Pd(II) and thus lessen the contribution of forward charge transfer from substrate to catalyst (e.g., π(arene) or σ(C–H) to d) as compared to reverse charge transfer from catalyst to substrate (e.g., d to σ*(C–H)).

The inclusion of additional metal complexes, including examples other than Pd(II) species, into this analysis provided some preliminary suggestion that more electron-rich complexes or more electrophilic complexes might cleave C–H bonds through geometrically similar AMLA/CMD-type transition states but with polarizations that still cluster into roughly two regions within the MOFJ plot. Metal complexes based on Cu(I) or Ag(I) have been demonstrated to cleave C–H bonds with experimental site selectivity that parallels Pd-catalyzed direct arylation favoring more acidic C–H bonds, and the C–H cleavage transition states involving these d10 species (TS-20 and TS-21, respectively) also locate in the same region as the direct arylation intermediates. On the other hand, d6 metal complexes reported in the literature to display more electrophilic type reactivity patterns, such as those based on Rh(III), Ir(III), and Ru(II),[37] react through transition states (TS-23, TS-24 and TS-26, respectively) that generally cluster in the region other electrophilic species, such as thioether-Pd(II) (TS-17) and cationic Pt(II) complexes (TS-27), also locate.

While additional study is needed to understand if ancillary ligands have the capacity to significantly shift the polarization of the AMLA/CMD-type transition states among d6 metal complexes, as seems to be the case for d8 Pd(II) complexes, a preliminary hypothesis was proposed stipulating that complexes favoring electrophilic or nucleophilic reactivity/selectivity behavior during catalytic base-assisted C–H functionalization might be classifiable into general groups on the basis of the metal’s electronic structure, charge, and ancillary ligands. For more nucleophilic metal complexes, such as d10 species and the organometallic d8 species associated with Pd-catalyzed direct arylation, a classic (“standard”) CMD transition state is predicted that should give rise to site selectivity favoring acidic C–H bonds. More electrophilic complexes, such as neutral or cationic d8 complexes featuring weak X-type ligands or d6 metal complexes, are predicted to favor substrates or sites with greater π-basicity. These reactivity trends are thought to reflect the changes in relative contributions of catalyst/substrate interactions with fluctuation in the frontier orbital levels of the catalyst. More electron-rich complexes should enhance interactions between filled metal and ligand orbitals with empty orbitals on the substrate, leading to a relatively larger contribution of reverse CT (Figure 13) at the C–H cleavage transition state. In this scenario, the polarization reflects a net shift of electron density onto the substrate. The degree to which this happens depends on the magnitude of the orbital interactions associated with reverse CT. More electrophilic metals, on the other hand, should exhibit enhanced interactions between filled orbitals on the substrate with vacant metal orbitals favoring more forward CT and a build-up of partial positive charge on the substrate at the transition state. These differences can also be correlated with changes in bond breaking and formation in the MOFJ plot: more advanced heterolysis of the C–H bond should be associated with partial negative charge accumulation on the ipso carbon while relatively advanced metal-carbon bond formation should be associated with the abovementioned build-up of partial positive charge on the substrate (i.e. concerted yet trending toward a Wheland intermediates). This preliminary model draws a parallel to the Ess, Goddard, and Periana concept for alkane C–H bond activation for which a continuum of mechanisms is related through the relative contributions of either forward or reverse CT, which accomodates a range of different transition states and mechanisms.

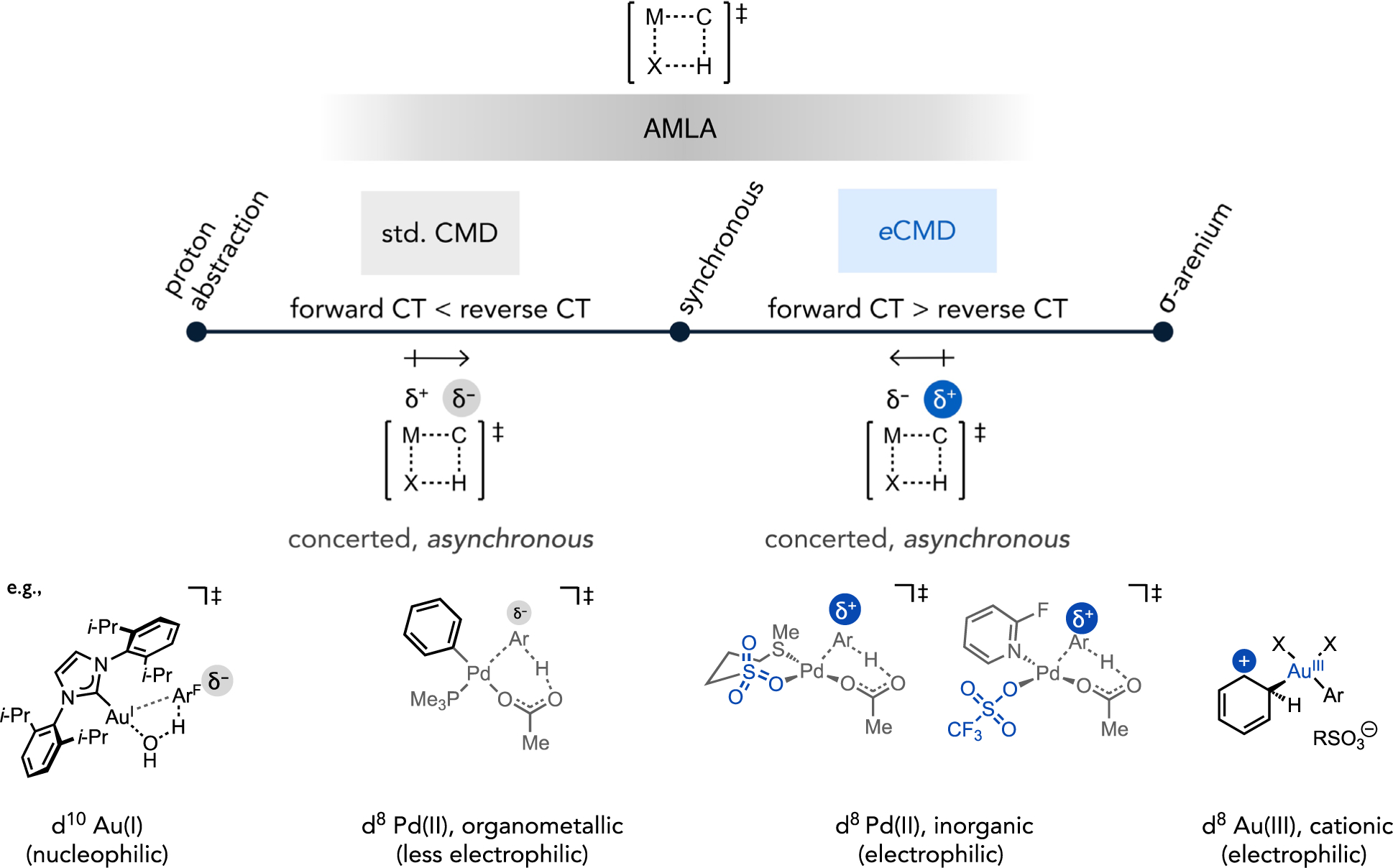

What follows from this hypothesis in the context of catalyst design and selectivity is that bifurcating a broader mechanistic model (AMLA/CMD/IES) that encompasses all base-assisted C–H cleavage mechanisms into different regions associated with distinct transition state polarization (Figure 22) could be useful to predict the favored reactivity patterns (i.e., site selectivity) for a given metal complex. For instance, Fagnou’s CMD model (referred to here as “standard CMD” for the purposes of disambiguation) was developed around a very specific reaction class, Pd-catalyzed direct arylation reactions, which display site selectivity (under kinetic control) favoring more acidic C–H bonds. This is distinct from the electrophilic reactivity patterns of many other base-assisted C–H cleavage reactions, including both classic cases (e.g., arene mercuration and DMBA cyclopalladation) as well as contemporary catalysts for C–H functionalization (e.g., Periana-Catalytica-type cationic Pt(II) complexes). In the subset of electrophilic reactions, the term electrophilic CMD (eCMD) has been proposed as a polarization-based term and model to describe complexes clustering in the upper region of the MOFJ analysis (Figures 20 and 21). The eCMD transition state is characterized by metal-carbon bonding that is more advanced than carbon-hydrogen cleavage relative to the standard CMD transition state. Thus, more partial positive charge is expected to build-up on the substrate in the asynchronous eCMD transition state that gives rise to electrophilic reactivity patterns favoring more π-basic substrates or sites.

Figure 22.

Proposal for a continuum of base-assisted C–H cleavage mechanisms demarcated by the relative extent of forward or reverse charge transfer (CT) between the interacting catalyst and substrate, which in turn can enhance, diminish or fully reverse the polarization in the transition state across a spectrum of concerted mechanisms with varying extent of asynchronicity.

Figure 21.

Expanded More O’Ferrall–Jencks analysis of AMLA/CMD-type transition states beyond the Pd(II) examples in Figure 20.

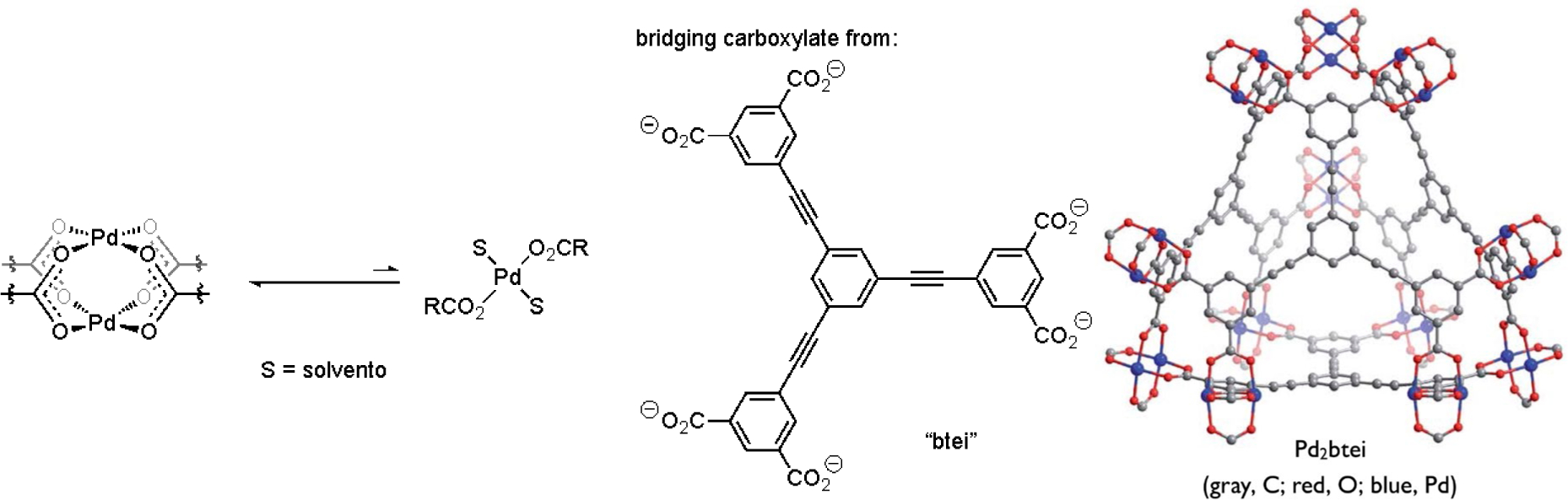

2.6. Multi-Metallic Pathways for Catalytic Processes Involving AMLA/CMD

Internal bases that facilitate AMLA/CMD-type mechanisms through favorable six-membered transition states are generally ambidentate, such as acetate that can coordinate a single metal center in either a κ1 or κ2 fashion or alternatively in a μ2 fashion that bridges two metal complexes. This latter coordination mode is widespread throughout group 8–11 metal chemistry, including a large majority of catalysts associated with the AMLA/CMD-type mechanism. The ease of access to polynuclear species assembled through the internal base for such C–H cleavage pathways opens the question about what role(s) multi-metallic complexes might play as on- or off-cycle catalytic intermediates. For instance, stronger internal bases should generally lower the AMLA/CMD energy barrier by facilitating C–H heterolysis. Variation of the basicity of this reacting ligand independent of the electrophilicity at the metal center is complicated due to their coordination in a monometallic catalyst. On the other hand, multi-metallic systems might hold the potential to decouple this compensatory effect, such as when the metal coordinated to the internal base is not the same metal that interacts with the substrate in the C–H bond cleavage event. It might also be the case that the optimal metal complex for a particular C–H activation of interest may not also be the optimal catalyst for other down-stream catalytic steps (i.e., insertion, transmetalation, reductive elimination). Multi-metallic systems also could be advantageous in this regard by the delegation of different catalytic steps to the most capable metal complex. Recent mechanistic studies of catalytic processes involving AMLA/CMD-type processes have uncovered a number of instances along these lines suggesting multi-metallic catalytic processes can enable unique properties versus monometallic systems.

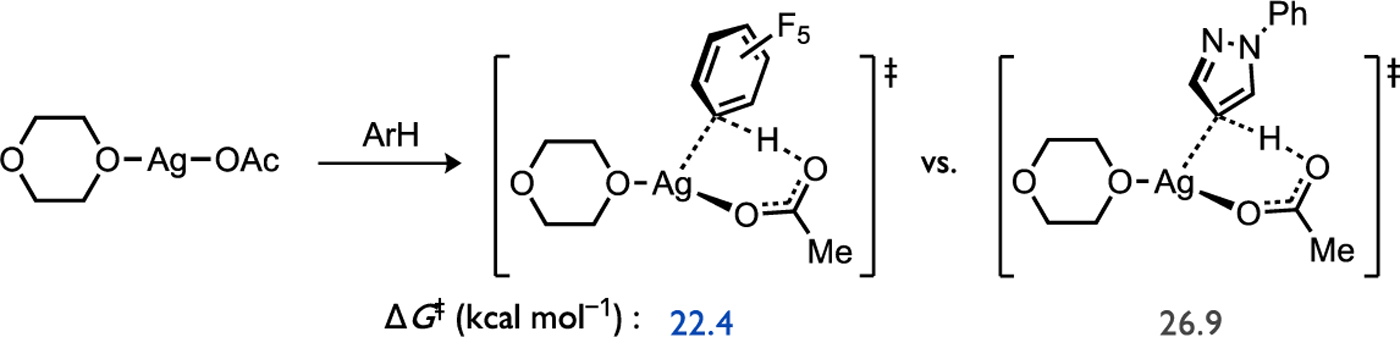

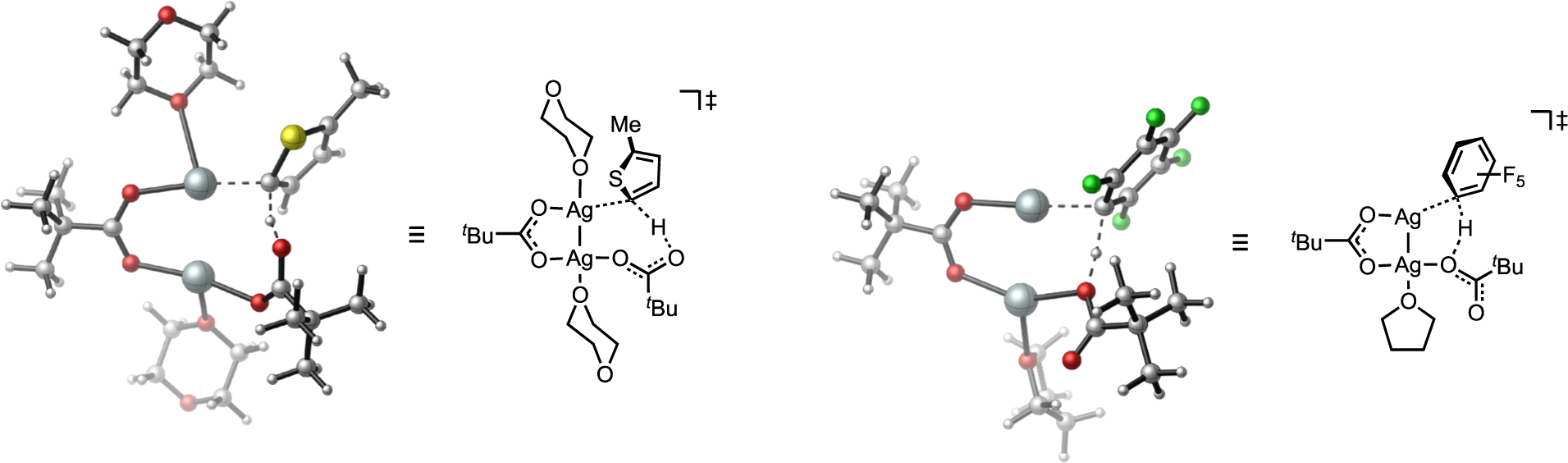

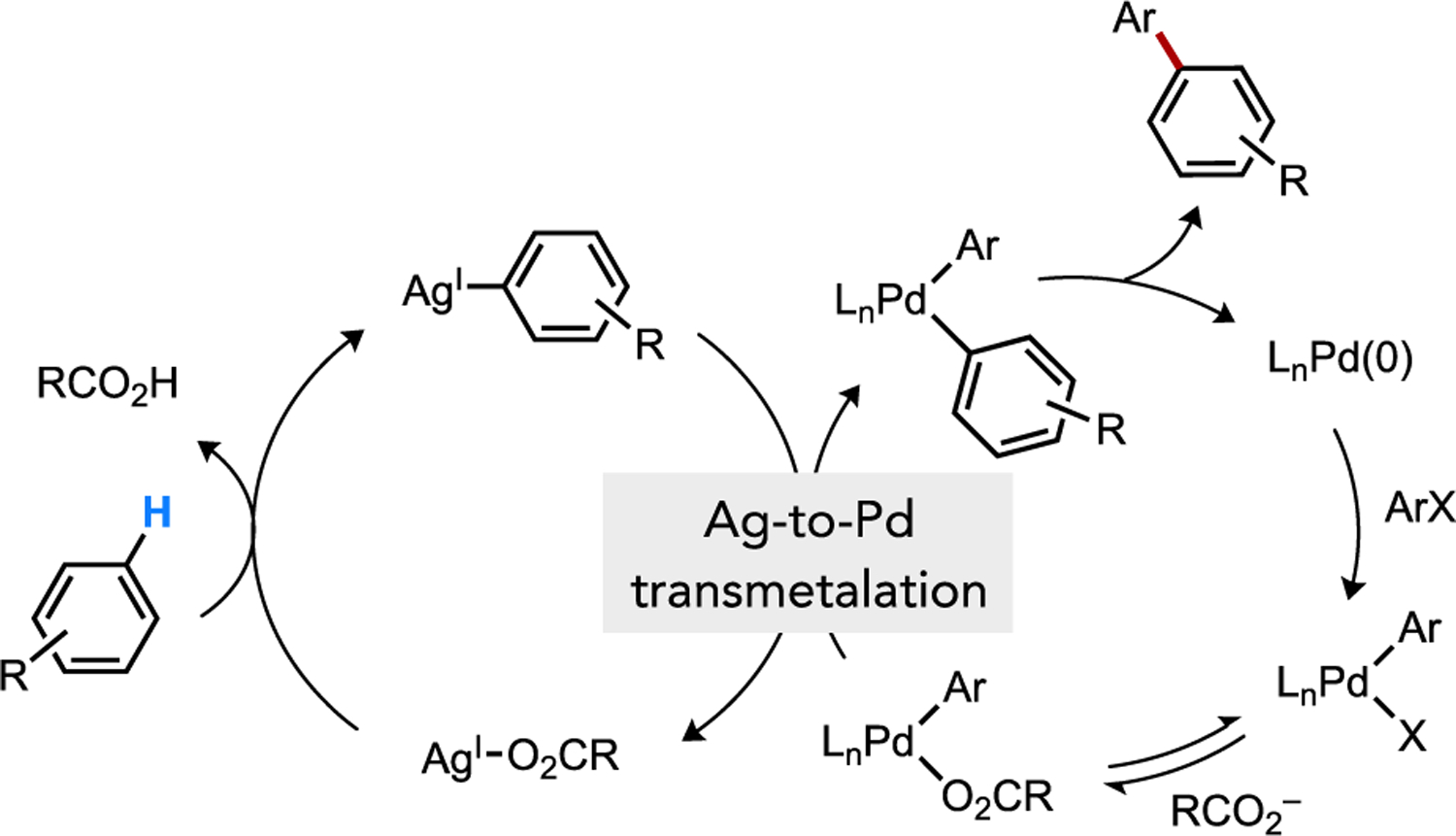

The use of Ag(I) salts as promoters in many CDC reactions is conspicuous. It is an essential choice for the terminal oxidant in many of these C–H coupling reactions, and studies have recently pointed to other roles for Ag(I) beyond providing thermodynamic driving force in oxidative CDC chemistry.[59, 63] Mechanistic experiments and computational investigations in independent reports by Hartwig, Larossa and Sanford established the viability of Ag(I)-carboxylate complexes to promote allylic or (hetero)arene C–H cleavage by a CMD mechanism.[62, 64] In such circumstances, the resultant organo-Ag(I) species formed by CMD can exchange its hydrocarbyl ligand by transmetalation to another transition metal complex (Pd, Au, etc.) competent to carry the organometallic fragment forward to C–C or C–X bond formation. A bimetallic pathway was estimated to be unfavorable in Sanford’s study (Figure 23), but dimeric complexes may still compete with monometallic pathways under other circumstances.[59]

Figure 23.

Examples of CMD C–H cleavage within a dinuclear Ag(I) pivalate complex where the internal base is not coordinated to the metal with the developing M–C bond.[62]

The presence of dinuclear Pd complexes in C–H functionalization reactions has frequently been noted, but their formation has often been thought to occur after a C–H functionalization step,[65] or their fragmentation has been proposed to occur prior to a C–H cleavage step at a monometallic species.[55, 66] Computational evaluation of AMLA/CMD-type C–H bond cleavage in dinuclear carboxylate-bridged Pd(II) complexes versus analogous monometallic pathways suggests energetic differences can be subtle.[67] However, studies by Lewis and Musaev have provided support for dinuclear Pd complexes coordinated by a MPAA ligand as potentially kinetically favored catalysts for AMLA/CMD-type C–H cleavage.[68]

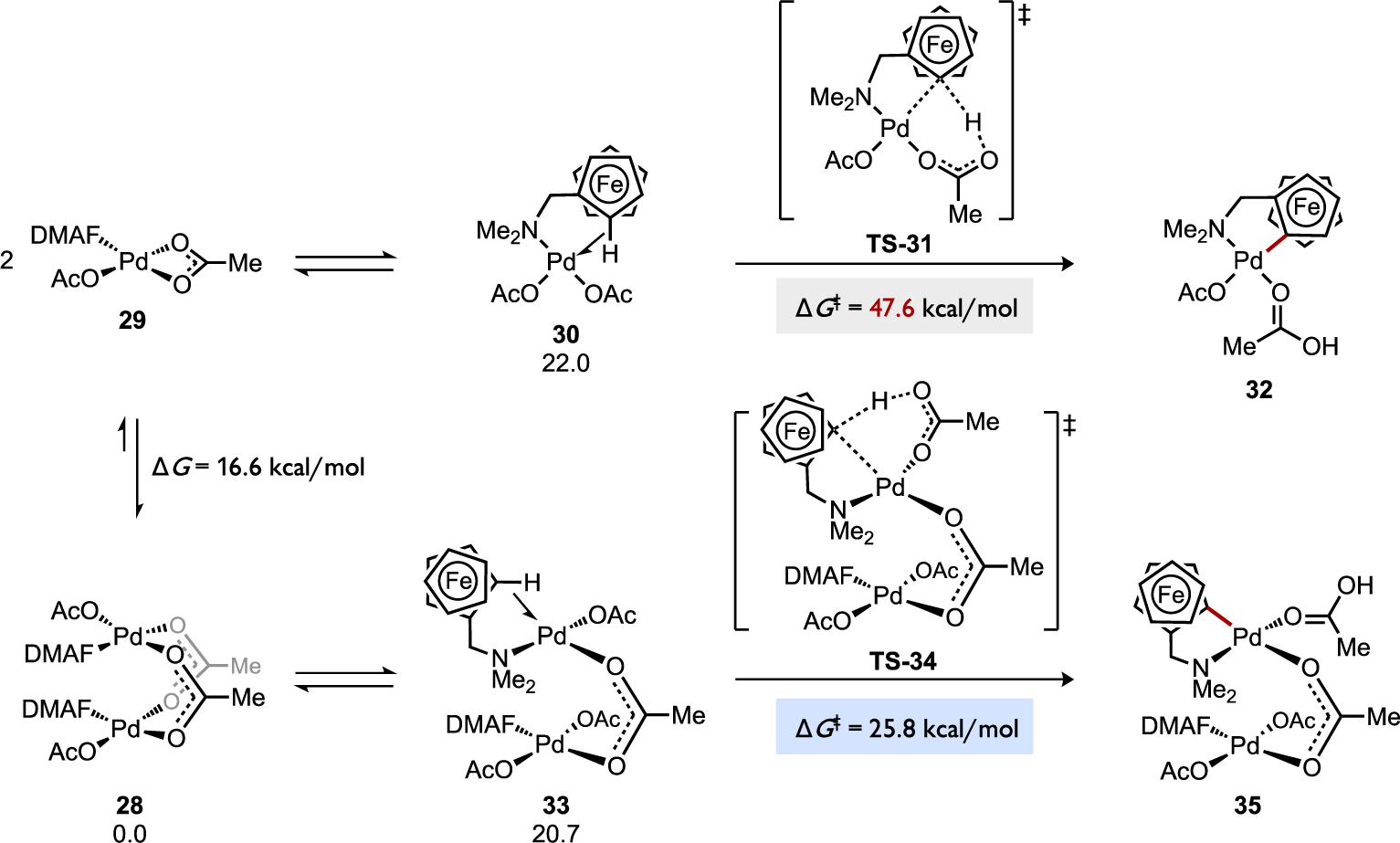

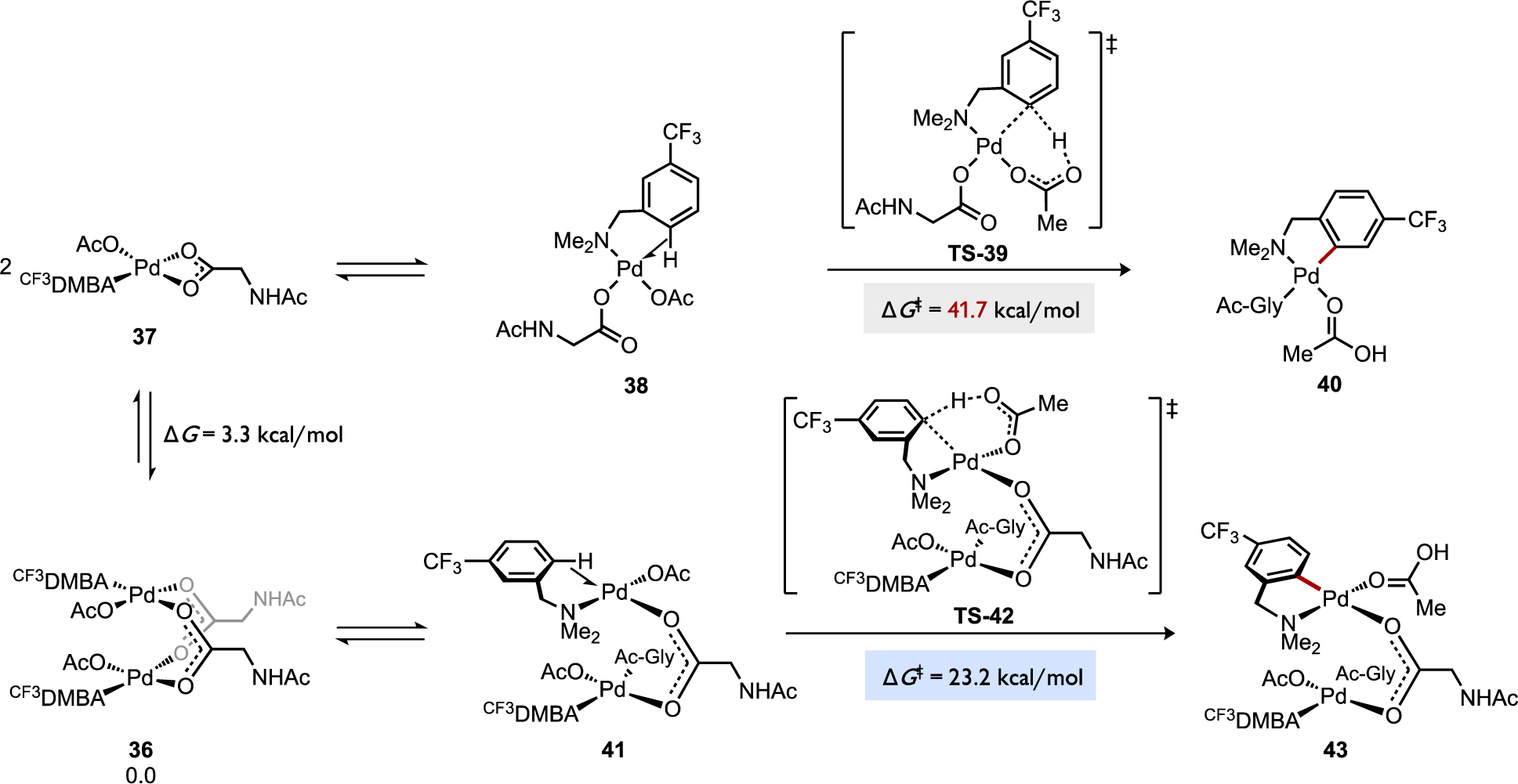

A cyclopalladation reaction involving Pd(OAc)2 and N,N-dimethylaminomethylferrocene (DMAF) (Figure 24) was calculated to undergo C–H cleavage through a dinuclear pathway that was much more favorable than the competing monometallic pathway (ΔΔG‡ = 21.8 kcal/mol) relative to a common intermediate, the dimeric complex [(κN-DMAF)Pd(κ1-OAc)(μ2-OAc)]2 (28).[68b] It should be noted that an earlier DFT study on cyclopalladation of a related substrate (DMBA) with Pd(OAc)2 reported an intrinsic energy barrier for a monometallic mechanism (ΔG‡ = 13.0 kcal/mol) relative to the agostic complex.[16] The intrinsic barrier for AMLA (eCMD) in the monometallic cyclopalladation reaction between DMAF and Pd(OAc)2 was calculated to be significantly different, ΔG‡ = 25.6 kcal/mol relative to the analogous agostic complex (κN,η2CH-DMAF)Pd(κ1-OAc)2 (30), yet this energy barrier nevertheless remains higher than the intrinsic barrier for the competing bimetallic AMLA (eCMD) pathway for DMAF cyclopalladation via the analogous agostic intermediate 33 (ΔG‡ = 5.1 kcal/mol). This data provides a compelling suggestion that the dinuclear pathway could be kinetically viable.[68b] Another study by Lewis and Musaev examined cyclopalladation in which an MPAA comprises the bridging ligand of dipalladium species (Figure 25). Cyclopalladation of 3-trifluoromethyl-N,N-dimethylbenzylamine (CF3DMBA) in the monometallic intermediate Pd(κN-CF3DMBA)(κ1-OAc)(κ2-Ac-Gly) (37) was calculated to occur with an overall C–H cleavage barrier via AMLA (eCMD) that was 18.5 kcal/mol higher than the corresponding reaction via a dinuclear analog, both pathways normalized to the common ground state complex [Pd(κN-CF3DMBA)(κ1-OAc)(μ2-Ac-Gly)]2 (36).

Figure 24.

Cyclopalladation of N,N-dimethylaminomethylferrocene (DMAF) at Pd(OAc)2 through competing mono- or bimetallic AMLA/eCMD pathways.[68b]

Figure 25.

Cyclopalladation of 3-trifluoromethyl-N,N-dimethylbenzylamine (CF3DMBA) at Pd(OAc)2 coordinated by an MPAA ligand (Ac-Gly-OH) through competing mono- or bimetallic AMLA/eCMD pathways.[68a]

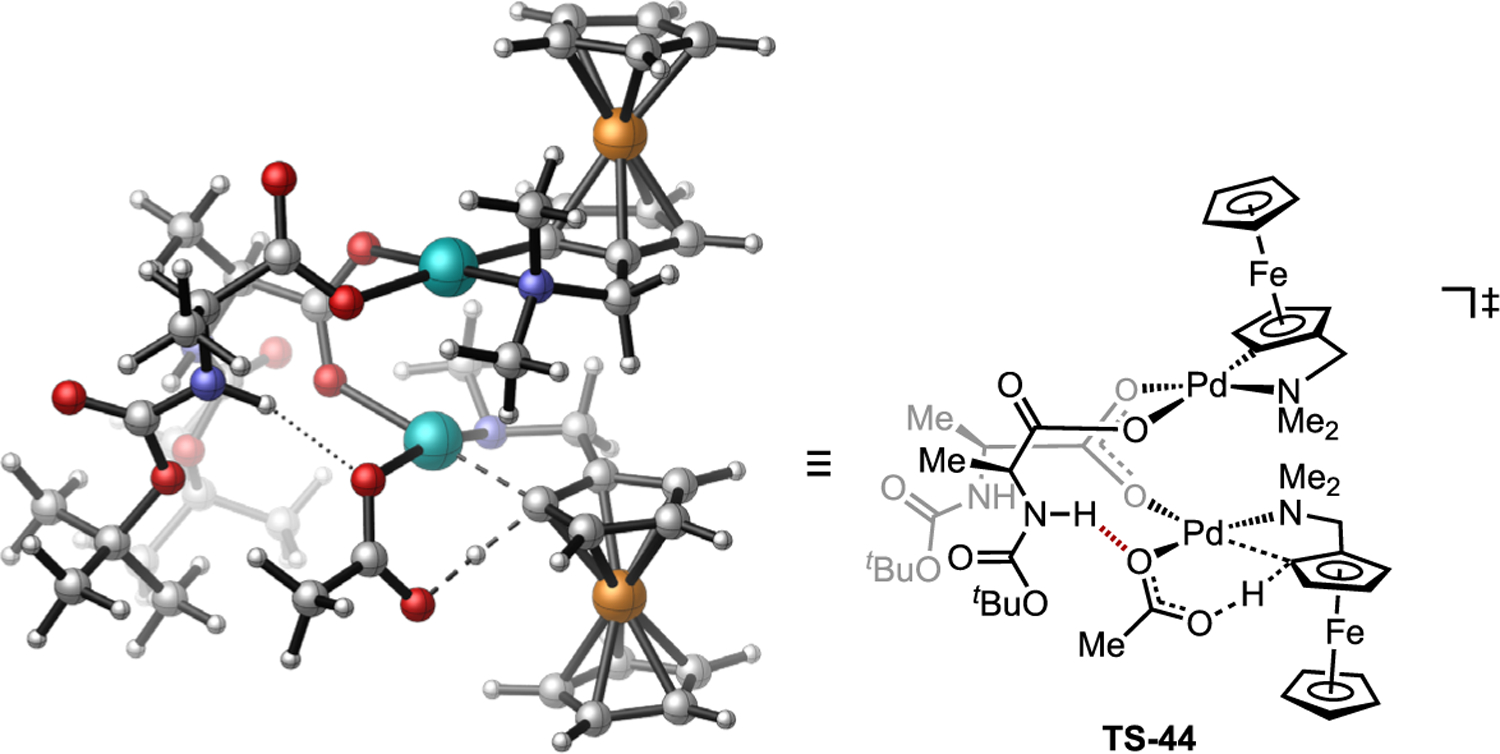

The coordination of an MPAA ligand to Pd is well-known to influence the rates of C–H activation,[48b] yet assembly of more reactive dinuclear structures provides new understanding of how of these ligand effects can influence reactivity. The stereoselectivity of cyclopalladation via AMLA (eCMD) was also examined in complexes coordinated by a chiral MPAA. The more favorable diastereomeric transition state leading to the observed major product was found to benefit from a favorable non-covalent interaction spanning from the “spectator” Pd center to the internal base participating in the C–H cleavage on the “active” Pd center within the initial dinuclear complex [Pd(κN-DMAF)(κ1-OAc)(μ-κ2-Boc-Ala)]2 leading to TS-44 (Figure 26) after the first cyclometalation activation step. This hydrogen bond is estimated to lower the transition state energy leading to the major stereoisomer of the organometallic product by ca. ΔΔG‡ = 3.2 kcal/mol versus an analogue lacking the hydrogen bonding interaction.[68b]

Figure 26.

Identification of a non-covalent interaction across the dinuclear complex that enhances the stereoselectivity in competing AMLA/CMD transition states. Note one N-methyl is omitted from reacting DMAF for clarity.[68b]

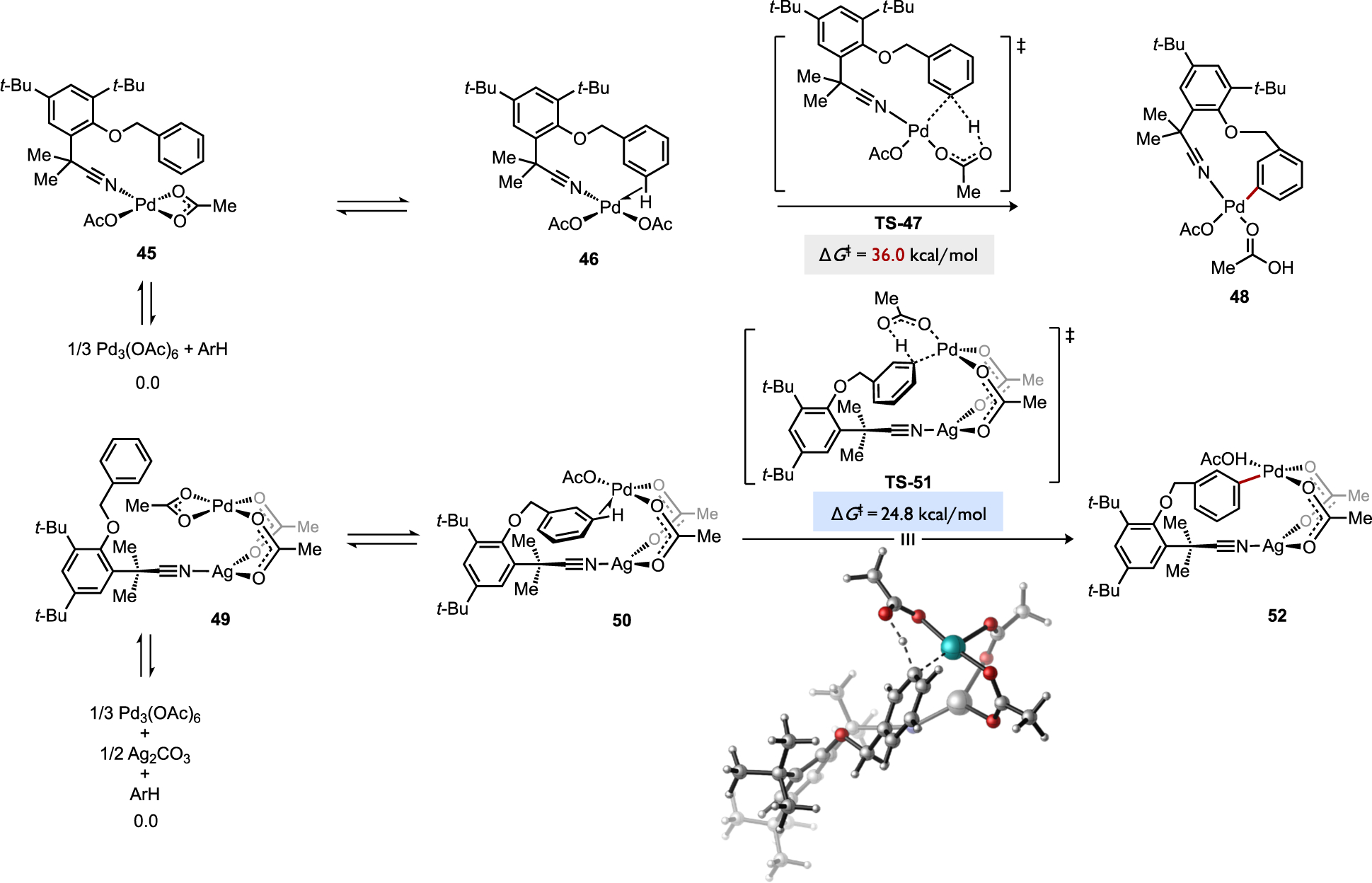

Heterobimetallic complexes have also been considered for their potential to cleave C–H bonds competitively with monometallic or homobimetallic pathways. A computational study by Yu and Houk on a meta-selective DHR reaction, one which leverages a unique nitrile templating group on the reacting arene, examined reaction pathways for C–H cleavage involving substrate bound to Pd(OAc)2, dimeric Pd2(OAc)4, heterobimetallic PdAg(OAc)3, and trimeric Pd3(OAc)6 complexes.[69] The reaction at the Ag/Pd heterobimetallic species was determined to be most favorable. In this pathway, the templating group coordinates to Ag while the Pd center supplies the internal base and accepts the incoming aryl bond at the C–H cleavage transition state, such as TS-51 in Figure 27. This heterobimetallic pathway correctly predicts a lower energy barrier to activation of the substrate’s meta C–H bond over the ortho or para positions (ΔG‡ = 24.8 versus 27.8 or 28.3 kcal/mol, respectively). Conversely, the monometallic pathway is calculated to proceed with higher energy barriers (i.e., TS-47) than the Ag/Pd heterobimetallic pathway favoring the ortho (ΔG‡ = 30.1 kcal/mol) over meta or para activation (ΔG‡ = 36.0 or 35.3 kcal/mol, respectively), which does not agree with the experimentally-observed high meta regioselectivity for the catalytic C–H alkenylation (m/(o+p) ≥ 90:10 for most examples).[70] While early studies on Pd-catalyzed C–H activation proposed almost exclusively monometallic mechanisms, computational and kinetic data now convincingly suggest multi-metallic species should also be considered as kinetically relevant intermediates. Such aggregates may be enabling to access complementary site selectivity versus mononuclear analogues. Future studies aimed at controlling or biasing the interchange of these various catalyst aggregation states could further leverage the potential of multi-metallic species in AMLA/CMD-type processes.

Figure 27.

Identification of a kinetically favorable heterobimetallic pathway for C–H cleavage during a meta-selective C–H alkenylation reaction.[69]

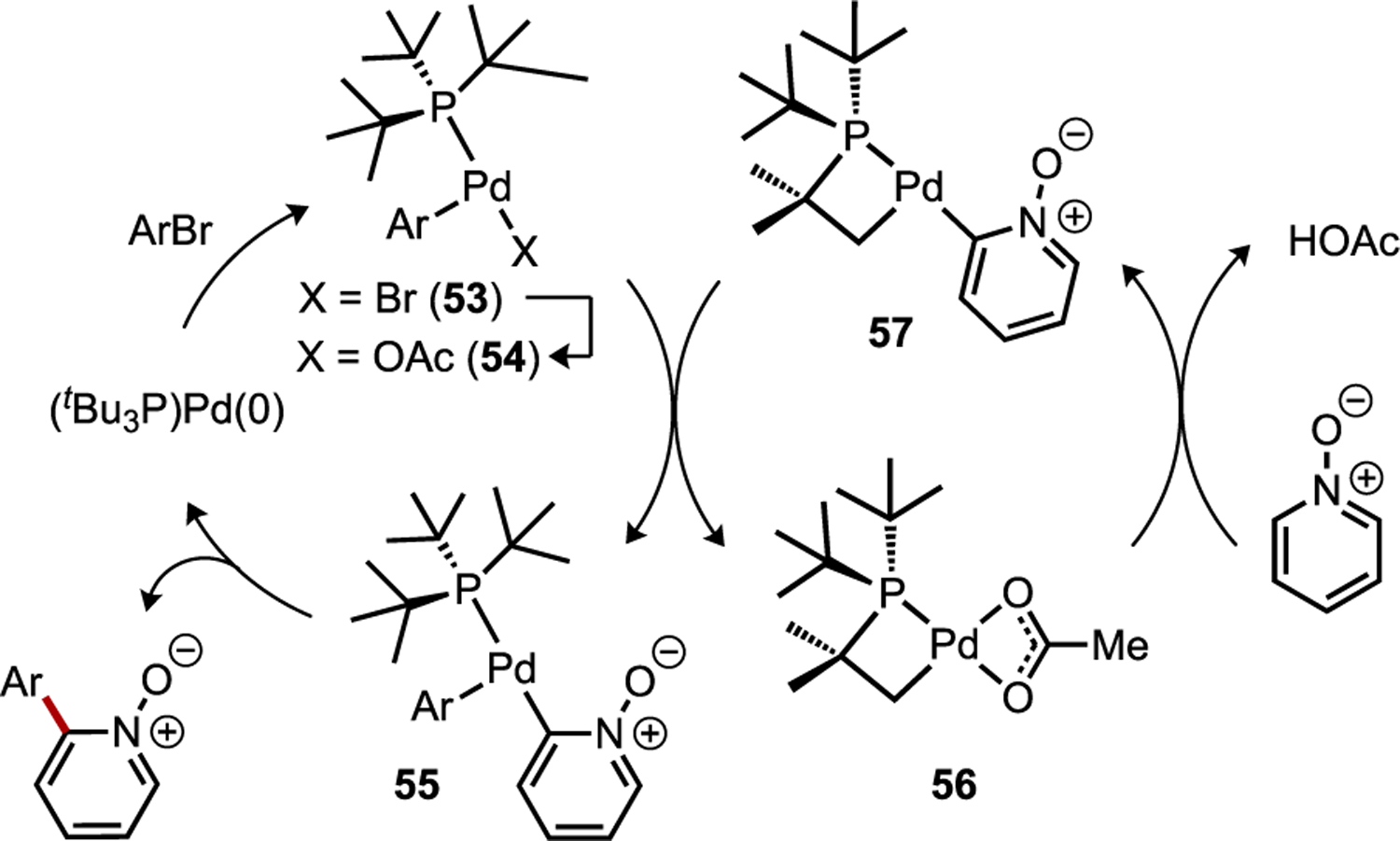

A different catalytic scenario in which multiple transition metal complexes can affect base-assisted C–H cleavage reactions is by cooperativity between structurally distinct mononuclear species.[72] For instance, Hartwig discovered the possibility that common phosphine-coordinated Pd catalysts may undergo in situ functionalization during direct arylation reactions to generate new catalytically-active species (Figure 28), such as by cyclopalladation at the ancillary ligand.[71] An earlier study had found that coordination of very hindered ligands, such as PtBu3, to Pd is associated with high calculated energy barriers in the CMD step between (tBu3P)Pd(Ph)(κ2-OPiv) and an electron-poor pyridine N-oxide substrate.[71a] The difference in CMD barriers between this hindered complex versus a phosphine dissociated analogue, Pd(ηO-DMAc)(Ph)(κ2-OPiv), was ΔΔG‡ = 11 kcal/mol, favoring the latter, suggesting that catalytic species other than the oxidative addition (OA) complex may be responsible for the CMD step. A subsequent study on direct arylation of pyridine N-oxide catalyzed by Pd(OAc)2/PtBu3 detected an induction period, which was correlated to the in situ formation of a new catalytic intermediate {Pd[κ2P,C-tBu2PC(CH3)2CH2](μ-OAc)}2 (56) by cyclopalladation.[71b] Kinetic studies indicated the presence of 56 led to an acceleration of turnover-limiting activation of the heteroarene substrate by CMD. DFT calculations on the two competing CMD pathways involving the typically proposed intermediate, (tBu3P)Pd(Ph)(κ2-OAc) (54), and the in situ generated metallocycle 56 supported the latter as being more reactive by ΔΔG‡ = 6 kcal/mol. Based on these observations, a catalytic process was proposed in which the palladacycle promotes CMD to generate 57 followed by Pd-to-Pd transmetalation with the OA complex (53/54) to give diaryl-Pd species 55 that generates product through C–C reductive elimination (Figure 28).

Figure 28.

Identification by Hartwig of a cooperative catalytic cycle for direct arylation that involves the in situ formation of a palladacycle that is more active toward CMD.[71]

A computational study by Gorelsky on truncated structures of these organopalladium complexes showed that the palladacycle generally exhibits lower CMD barriers for a variety of heteroarene substrates.[73] For instance, Pd[κ2P,C-Me2PCH2](κ2-OAc) underwent more favorable CMD compared to (PMe)3Pd(Ph)(κ2-OAc) (11) in reactions with C6F5H, C6H6, or thiophene by ΔΔG‡ = 0.7, 1.5, and 1.0 kcal/mol, respectively.[74] While the reactions first reported by Fagnou for direct arylation of pyridine N-oxides involved, specifically, a PtBu3-coordinated Pd catalyst,[75] a wide range of other phosphine ligand structures are also known to be susceptible toward in situ modifications (i.e., cyclometalation) when coordinated to a transition metal.[76] It is thus possible that cooperative catalysis involving multiple catalytically active species could occur in other CMD reactions as a result of in situ ligand modifications. Cooperativity of this sort is also not limited to phosphine-coordinated Pd catalysts. Direct arylation using (α-diimine)Pd catalysts has also been suggested to benefit from cooperativity between multiple catalytic species, though unambiguous characterization of the CMD-active metal complex was not established in this study.[77]

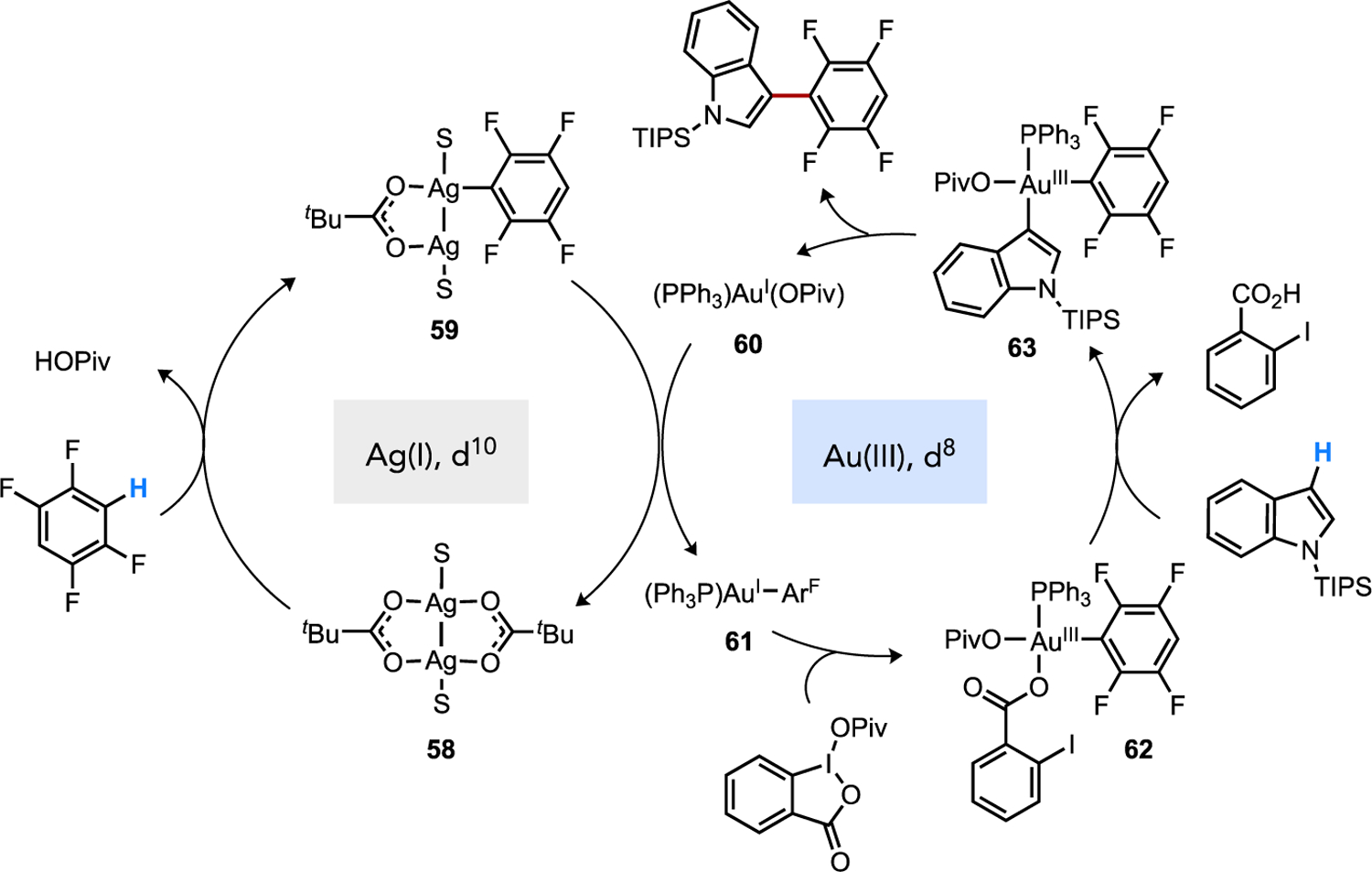

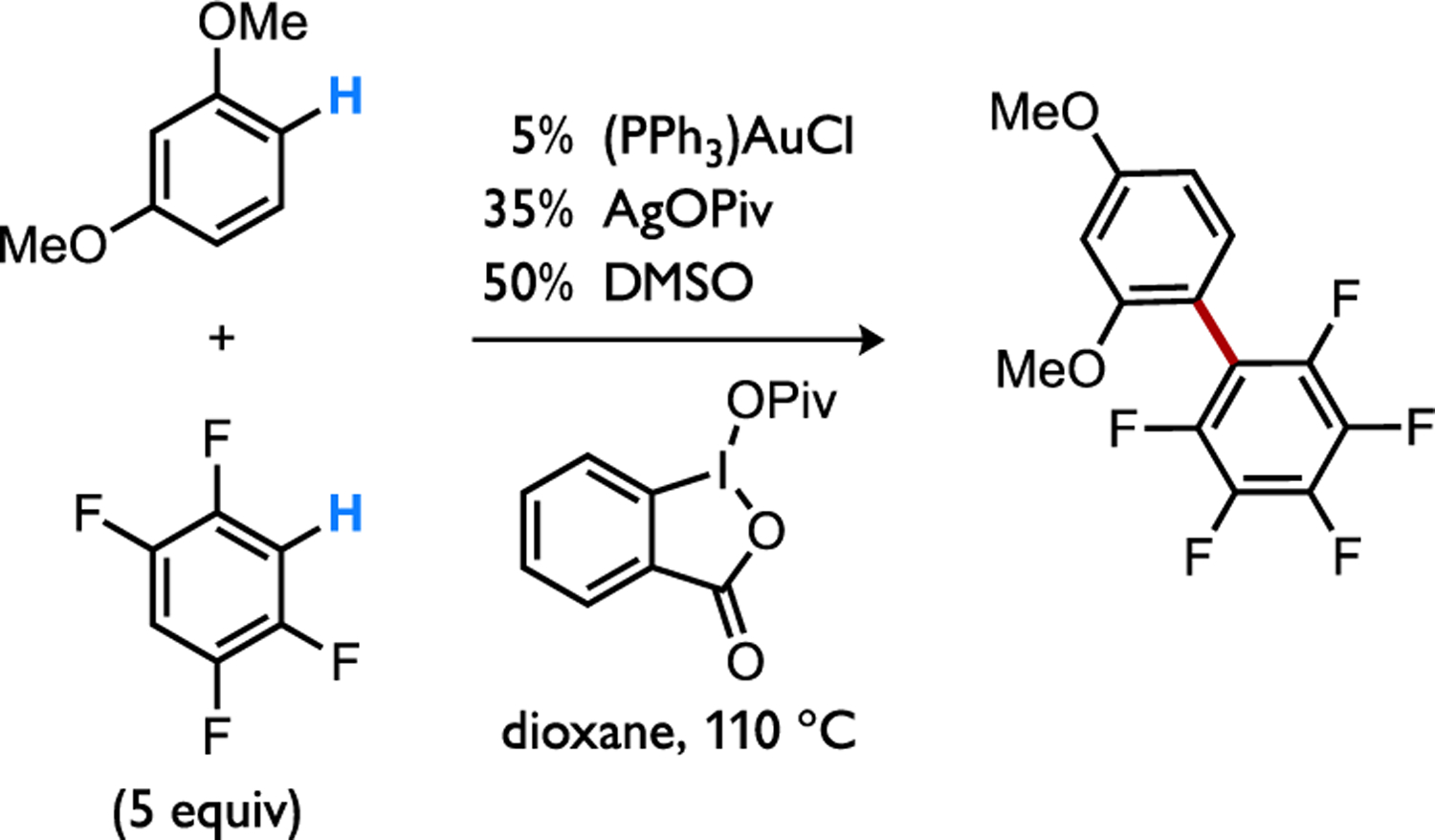

The competency of Ag(I)-carboxylate complexes to facilitate CMD, already discussed above,[59, 63] has been implicated in direct arylation reactions involving Ag additives through a cooperative mechanism. Larrosa proposed that Ag-to-Pd transmetalation can occur after CMD at Ag(I) to furnish a diorgano-Pd intermediate poised to undergo C–C reductive elimination (Figure 29). A similar cooperative scenario has been suggested in cross-dehydrogenative coupling of two (hetero)arenes as well, such as in gold-catalyzed reactions in the presence of a Ag(I) promoter.[59, 63d] Calculations on a Ag(I)-pivalate species support a favorable cooperative system where this electron-rich d10 species (i.e., 58) can promote standard CMD that favors an electron-poor arene (e.g., 1,2,4,5-C6F4H2) over an electron-rich heteroarene (e.g., C3 in N-TIPS indole) with a calculated ΔΔG‡ = 2.7 kcal/mol (Figure 30).[63d] After Ag-to-Au transmetalation between 59 and 60 to form 61 then oxidation, the organo-Au(III) species 62 is predicted to undergo a electrophilic auration then deprotonation by external base that strongly favors the electron-rich substrate (ΔΔG‡ = 19.2 kcal/mol). The resultant diaryl-Au(III) species 63 then generates product by C–C reductive elimination.

Figure 29.

Cooperative catalysis during direct arylation involving CMD at Ag(I) then Ag-to-Pd transmetalation.[64b]

Figure 30.

Cooperative catalysis involving two different base-assisted C–H cleavage steps at distinct metal complexes. Standard CMD is proposed to occur at the more nucleophilic Ag(I) co-catalyst followed by electrophilic auration subsequent to Ag-to-Au transmetalation. Adapted from Ref. [63d].

A distortion/interaction analysis on the C–H auration step indicated this transition state is characterized by an interaction energy (ΔEint) term that is significantly larger than what is typically associated with standard CMD transition states. A mechanistic study by Carrow recently implicated large ΔEint in concerted, base-assisted C–H cleavage pathways via the proposed eCMD variant of a general base-assisted mechanism that favors reactions with more π-basic substrates or sites.[34] Thus, care should be exercised to characterize whether the catalytic intermediate preceding C–H heterolysis is best described as a π- versus σ-complex. A fuller understanding of the reactivity consequences for catalysts favoring eCMD versus SEAr is yet to be established, though carbocation rearrangement in the latter mechanistic manifold could be one possible difference relative to concerted pathways.[78] It has classically been the case that cross-C–H/C–H coupling between two electronically-differentiated (hetero)arenes has defaulted to mechanistic rationalizations involving an SEAr mechanism in one catalytic step to account for selection of an electron-rich substrate. However, a reversal of polarization within a general AMLA/CMD concerted mechanism might also account for selectivity favoring a π-basic substrate (via eCMD) when the catalytic step involves a sufficiently electrophilic metal complex (see Figure 22). Likewise, selection of sites with more acidic C-H bonds (standard CMD) is well established when the catalytic step involves a more nucleophilic metal complex, such as Ag(I) complexes or organometallic Pd(II).

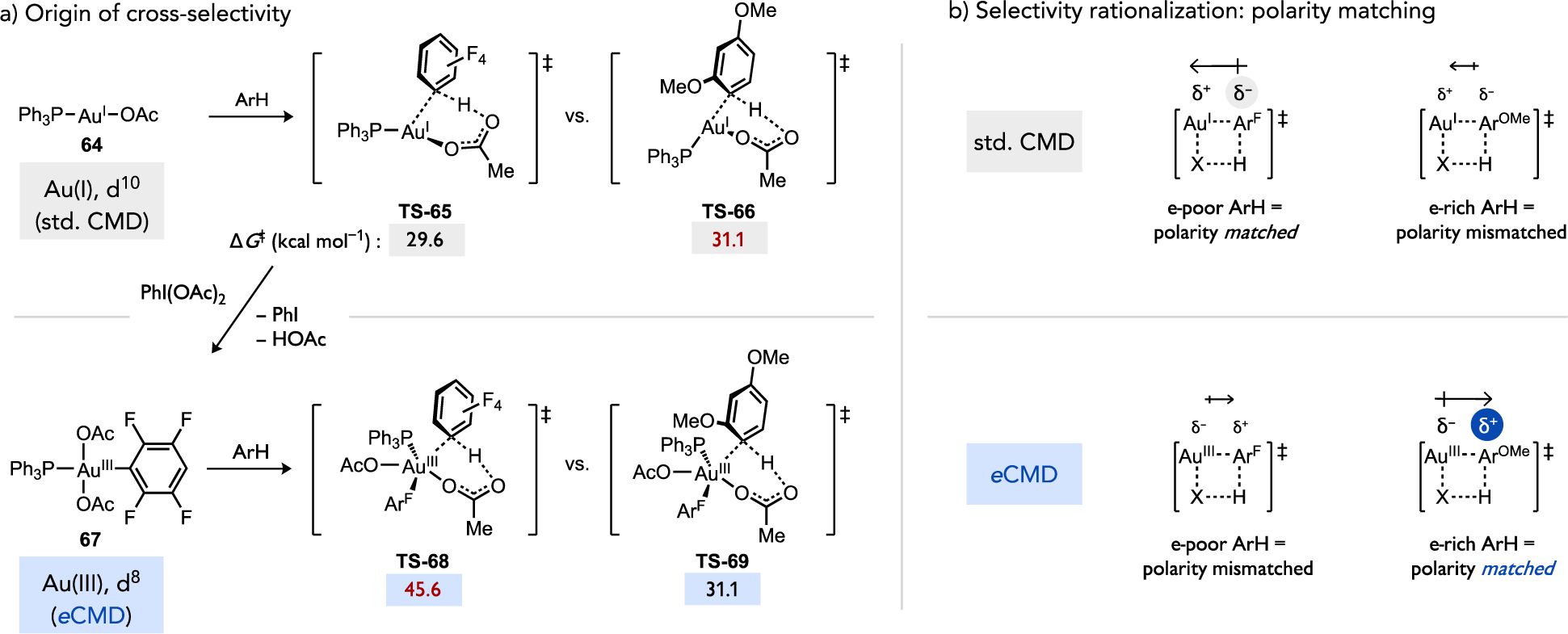

The catalytic C–H/C–H coupling via an Au(I)/Au(III) redox couple (Figure 31) might also occur through a mechanism in which the gold complex is responsible for cleaving both C–H bonds in either substrate.[79] In this scenario, the first C–H bond cleavage would occur at a nucleophilic d10 Au(I) intermediate 64, presumably via standard CMD (Figure 32a), which favors the electron-poor arene via TS-65 over an electron-rich arene via TS-66 (ΔΔG‡ = 1.5 kcal/mol).[79b] An d8 Au(III) complex 67 generated by subsequent oxidation might then become sufficiently electrophilic to switch the polarization of the concerted C–H cleavage transition state to favor eCMD through TS-68 versus the alternative TS-69 involving instead the electron-poor arene (ΔΔG‡ = 14.5 kcal/mol). While this hypothesis requires experimental and theoretical scrutiny, it would then be unnecessary to assume by default that SEAr steps occur when a catalyst selects for an electron-rich substrate. Redox processes and ancillary ligand substitutions that occur while the metal complex traverses the catalytic cycle could instead sufficiently perturb the catalyst electronic structure such that a switch occurs between C–H bond cleavage by the same general concerted, base-assisted mechanism but with a differing sense of polarization between catalyst and substrate (std. CMD or eCMD) that enforces a change in the preferred substrate or site (Figure 32b). This concept could be thought of as “polarity matching” where a more nucleophilic catalytic intermediate reacting through standard CMD is better matched with a more electron-poor substrate that accommodates build-up of negative charge at the C–H cleavage transition state (i.e., forward CT > reverse CT). Likewise, structural changes to the catalytic intermediate that render it more electrophilic could then switch the preferred, polarity matched substrate to be a more electron-rich arene that would better accommodate build-up of positive charge in the C–H cleavage transition state by eCMD (forward CT < reverse CT).

Figure 31.

Illustrative example of an Au/Ag co-catalyzed cross-dehydrogenative coupling.[79]

Figure 32.

(a) Calculated activation energies for a Ag(I) or Au(II) complex to activate the electron-poor or electron-rich (hetero)arene in Larrosa’s cross-dehydrogenative coupling method shown in Figure 31 and (b) potential origin of selectivity based on a redox-dependent switch between standard CMD and eCMD.

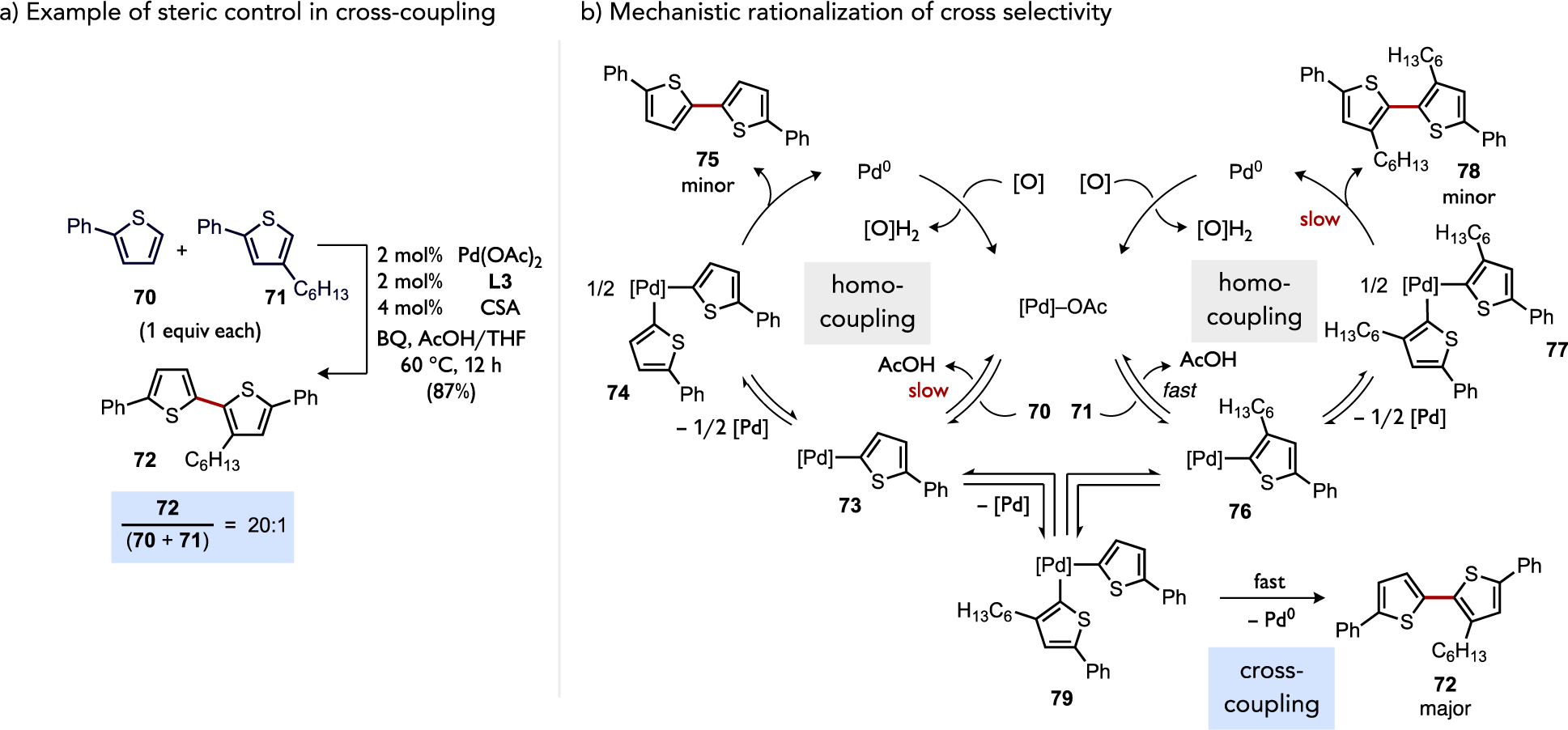

Cross selectivity in reactions involving C–H activation frequently rely on differentiation of substrates with substantial electronic property differences, but discrimination of subtler variations or control based on other factors remains desirable for broader utility. A gold-catalyzed method to achieve selective cross-coupling between two electron-rich arenes has been reported by Lloyd-Jones and Russell, which proceeds by a catalytic pathway involving C–Si auration then C–H auration at an Au(III) species.[80] Davies demonstrated the feasibility of ligand-switchable site selectivity using paddlewheel dirhodium(II) tetracarboxylate catalysts in Rh-carbenoid C–H insertions, for instance by distinguishing between unactivated tertiary C–H bonds over methylene C–H bonds.[81] This remarkable catalyst tunable selectivity was attributed to a combination of factors, which include a sterically-accessible pocket near the reactive carbenoid moiety and the superelectrophilic nature of the catalyst when assembled into the dirhodium structure.[82] In another area, the feasibility of sterically-controlled cross selectivity during C–H/C–H coupling of thiophenes was supported by a competition between an unhindered (70) and an ortho-substituted (71) thiophene (Figure 33a).[34] The high selectivity for the cross product 72 over the two possible homocoupling products 75 or 78 (20:1) necessitates that at least one C–H cleavage step in the catalytic process be kinetically faster for the more hindered 2-phenyl-3-hexylthiophene substrate 71. Cross selectivity has generally been accommodated by invoking two distinct C–H activation mechanisms at a single metal center. Experimental and computational mechanistic data for this cross-selective (thioether)Pd-catalyzed thiophene coupling example, however, supported a catalytic process for which the mechanism of C–H cleavage is the same for both thiophene substrates and thus the origin of selectivity (Figure 33b) differed from what is classically proposed.

Figure 33.

(a) Example of a thiophene C–H/C–H coupling for which a more hindered substrate is preferentially engaged by the catalyst and (b) a proposed catalytic network that rationalizes the origin of high cross-selectivity.[34]

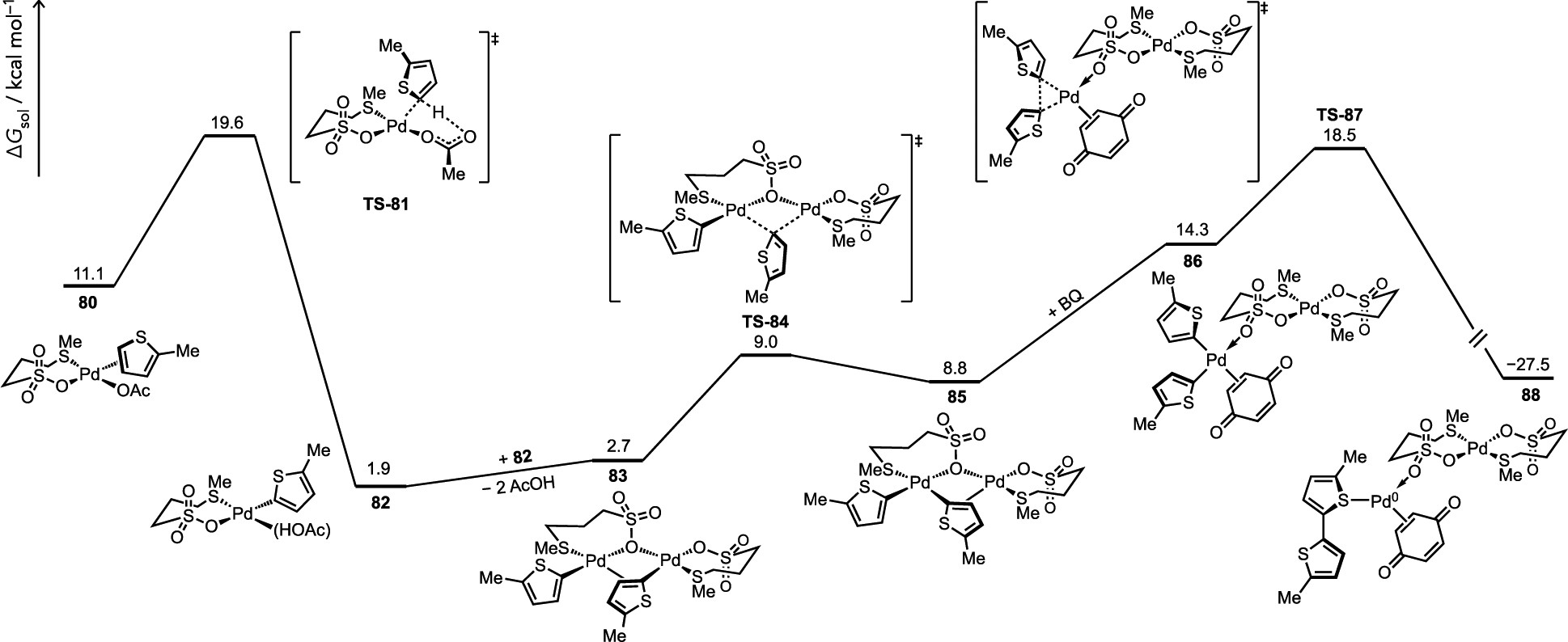

A mechanism for thiophene C–H/C–H coupling shown in Figure 34 was proposed when using a thioether-coordinated (e.g., L3 = MeS(CH2)3SO3–) Pd(II) catalyst.[34] Notable mechanistic observations included (i) a second-order dependence of the rate on [Pd], (ii) benzoquinone accelerated the rate despite the fact oxidation of Pd(0) was not a kinetically relevant catalytic step, and (iii) DFT calculations suggest Pd-to-Pd transmetalation is facile versus C–H cleavage. It was thus proposed that reductive elimination (RE) was the turnover-limiting and selectivity-determining step in this method. The origin of cross-selectivity for bithiophene 72 (see Figure 33a) can then be rationalized by faster C–H cleavage in the more hindered, yet more π-basic substrate (71) by an eCMD mechanism. However, the pathway to formation of homocoupling product 78 where intermediate 76 undergoes transmetalation with itself subsequently encounters a kinetically disfavored RE step via the hindered intermediate 77. The potential for reversibility in steps leading up to C–C bond-forming RE was suggested by a significant solvent isotope effect that correlates to a deceleration of protodemetalation (the microscopic reverse of C–H cleavage) in the presence of d4-acetic acid solvent.

Figure 34.

Thiophene C–H/C–H coupling catalyzed by a thioether-Pd catalyst via a bimetallic pathway, which establishes the potential for selectivity-determining reductive elimination at low [Pd] where flux through bimetallic steps becomes relatively slow versus monometallic steps. Free energies are relative to the dimeric ground state complex [Pd(L3)(μ2-OAc)]2.[34]

Upon protodemetalation of intermediate 76, it then becomes possible for the regenerated Pd(L3)(OAc) catalyst to react through a kinetically slower pathway with the less π-basic yet less hindered thiophene 70 to generate intermediate 73. Following transmetalation between two non-equivalent organopalladium species (73 and 76) to generate an unsymmetrical diarylpalladium intermediate 79, a faster RE step is then possible to form the major cross product 72. This bimetallic pathway mirrors what Stahl previously elucidated for the homocoupling of o-xylene catalyzed by 2-fluoropyridine-coordinated Pd(OAc)2.[83] These studies highlight the importance of ancillary ligand development specifically tailored for oxidative catalysis that can enable reactions in which C–H activation is kinetically fast relative to other catalytic steps, which may potentially offer more avenues by which selectivity can be controlled in non-directed C–H functionalization.[84]

2.7. Impact of Catalyst Speciation Control

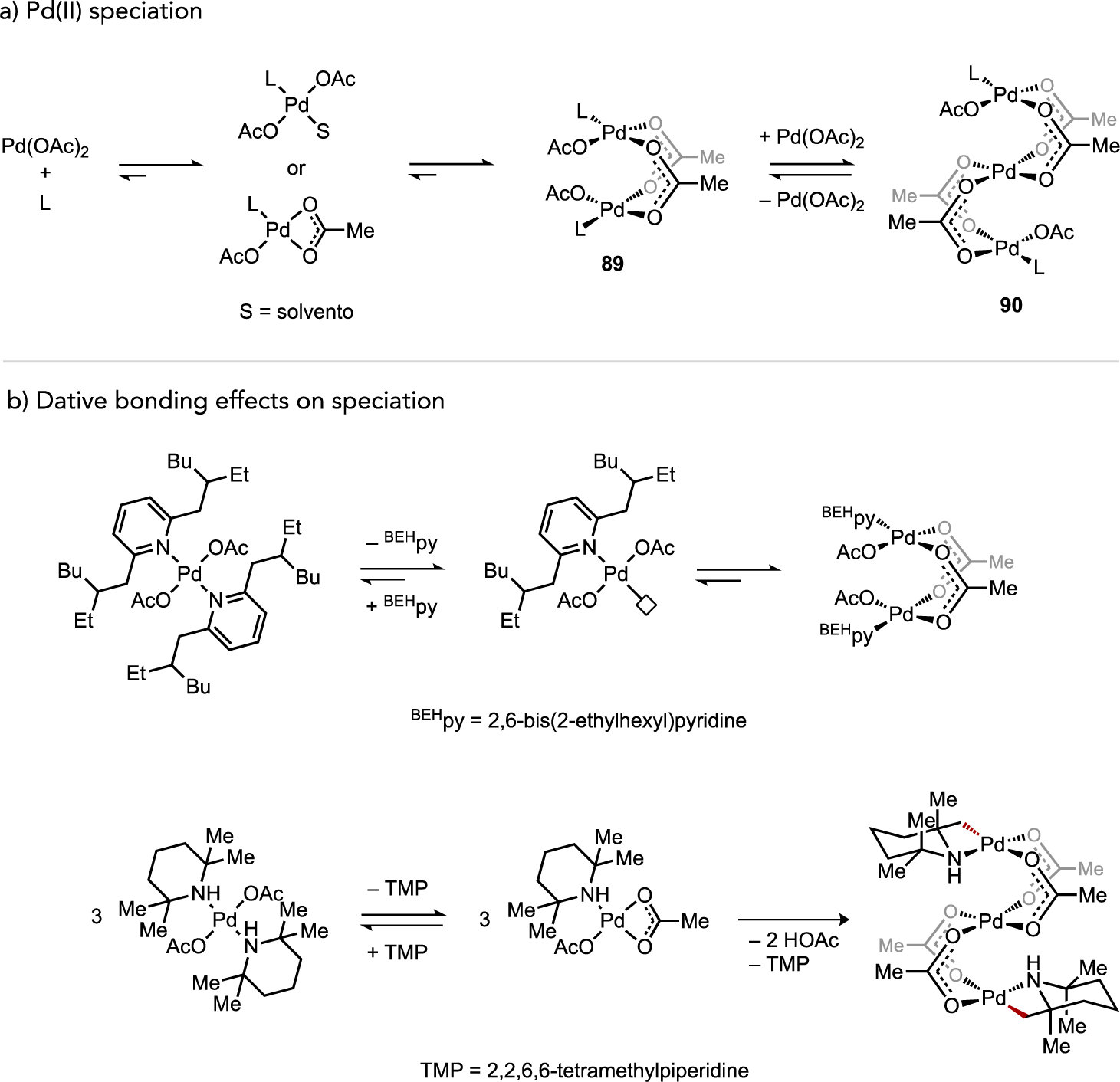

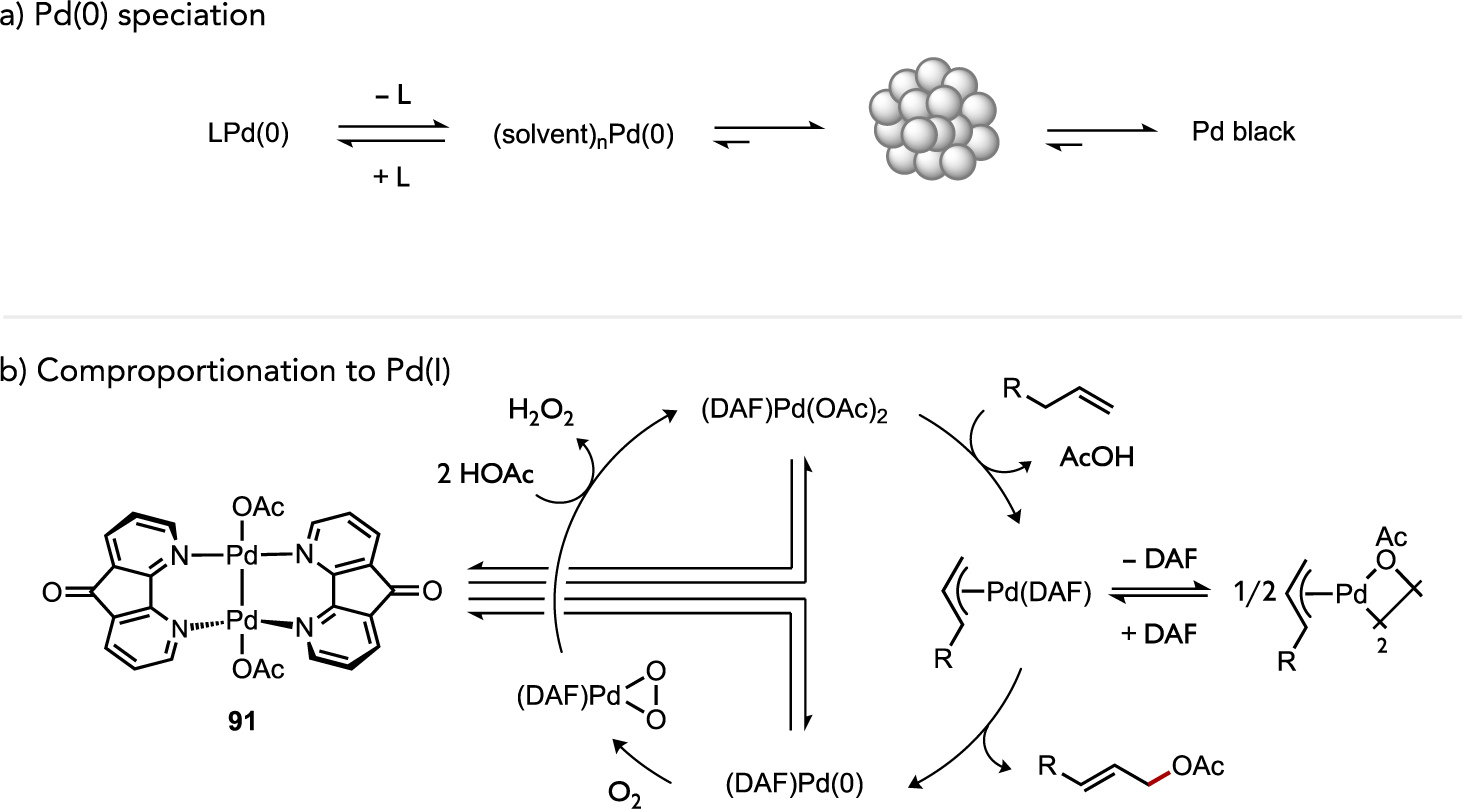

While catalyst speciation can in certain cases generate kinetically advantageous multi-metallic complexes (vide supra), metal aggregates may also constitute off-cycle catalytic reservoirs under circumstances where a mononuclear species is more reactive. For instance, di- and trinuclear Pd complexes bridged by μ-carboxylato ligands (i.e., 89 and 90) are commonplace, such as representative examples shown in Figure 35a. Kinetic data in studies of C–H acetoxylation, C–H alkenylation, or C–H/C–H coupling reactions[34, 47d, 54–55] implicated such aggregates as inactive off-cycle intermediates that must fragment to a generate an active mononuclear on-cycle catalyst. One role of ancillary ligands in these reactions may thus correspond to their ability to facilitate deaggregation, such as through their trans effect on a bridging carboxylato ligand. However, over-coordination of dative ligands[34, 54–55] or Lewis basic substrates[85] can lead to coordinatively-saturated mononuclear species that are also inactive (Figure 35b). As such, it is generally unlikely catalyst deaggregation in a homogeneous catalytic process can be addressed simply by employing a large excess of dative ligand. A need thus remains in this area to better understand how ancillary ligand structures can be exploited to strike a fine balance of speciation control between more and less active aggregation states while preserving access to open coordination sites at the transition metal for substrate binding and activation.

Figure 35.

(a) General representation of equilibria by which Pd(II) speciation occurs through ancillary ligand association or dissociation and (b) illustrative examples of hindered ancillary ligand or Lewis basic substrate effects on coordinatively-saturated monometallic species.[47c, 86]