Abstract

Background/purpose

The purpose of this study was to determine the pathogens and to estimate the incidence of pediatric community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in Taiwan.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted at eight medical centers from November 2010 to September 2013. Children aged 6 weeks to 18 years who met the radiologic criteria for pneumonia were enrolled. To detect classical and atypical bacteria and viruses, blood and pleural fluids were cultured, and respiratory specimens were examined by multiple conventional and molecular methods.

Results

At least one potential pathogen was identified in 705 (68.3%) cases of 1032 children enrolled, including bacteria in 420 (40.7%) cases, virus in 180 (17.4%) cases, and mixed viral-bacterial infection in 105 (10.2%) cases. Streptococcus pneumoniae (31.6%) was the most common pathogen, followed by Mycoplasma pneumoniae (22.6%). Adenovirus (5.9%) was the most common virus. RSV was significantly associated with children aged under 2 years, S. pneumoniae in children aged between 2 and 5 years, and M. pneumoniae in children aged >5 years. The annual incidence rate of hospitalization for CAP was highest in children aged 2–5 years (229.7 per 100,000). From 2011 to 2012, significant reduction in hospitalization rates pertained in children under 5 years of age, in pneumonia caused by pneumococcus, adenovirus or co-infections and complicated pneumonia.

Conclusion

CAP related pathogens have changed after increased conjugated pneumococcal vaccination rates. This study described the latest incidences and trends of CAP pathogens, which are crucial for prompt delivery of appropriate therapy.

Keywords: Age, Community-acquired pneumonia, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Virus

Introduction

Childhood community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a common and serious health care problem, responsible for one fifth of children's deaths around the world.1 Even as recently as in 2015, pneumonia accounted for 15% of all deaths of children under 5 years old, killing an estimated 922,000 children in this age range.2 Despite this large disease burden, critical gaps in our knowledge about pediatric pneumonia persist.3 CAP is usually caused by bacterial infection, and Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common pathogen in the pediatric population.4 , 5 Nevertheless, pneumonia of viral origin, including influenza virus, adenovirus, human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), are often endowed with similar radiographic findings.6 , 7 In recent years, improvement in the sensitivity and specificity of molecular methods has provided new opportunities to delineate the causative CAP pathogens. It is becoming evident viruses are also important pathogens of CAP in children.7 , 8 This has also helped to uncover the interplay among the different pathogens during acute respiratory infections.8 , 9

The incidence estimates of pediatric CAP hospitalizations based on prospective data collection are limited.10 We conducted a prospective, multicenter study in Taiwan and aimed to perform a comprehensive analysis on the incidence rates and the pathogens of pediatric CAP in Taiwan. At the time of the study, pneumococcus conjugated vaccine (PCV) was only available in the private market (approximately 16.2% in 2008, 22.3% in 2009, 30.2% in 2010, and 33.6% in 201111 and 40% in 2012 of children less than 5 years of age received one or more doses of the PCV7 or PCV13 vaccine, manufacturer estimates; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc., a subsidiary of Pfizer, Inc., Taiwan). We also compared and analyzed the demographic, clinical, and laboratory features of children with different etiologies.

Materials and methods

Study design

From November 2010 to September 2013, children aged 6 weeks to 18 years who met the World Health Organization's radiologic criteria for pneumonia12 were prospectively enrolled at eight participating medical centers, including Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital Linkou branch, National Taiwan University Hospital, Mackay Memorial Hospital, China Medical University Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital, National Taiwan University Hospital Yun-Lin Branch, National Cheng-Kung University Hospital, and Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung branch. These eight medical centers belong to the Taiwan Pediatric Infectious Disease Alliance (TPIDA), a study group funded by the National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan. Children were excluded if they had chronic renal failure, dialysis, indwelling devices, thalassemia major, chronic cardiovascular diseases, chronic lung disease of prematurity, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, congenital immunodeficiency, HIV infection, asplenia or malignancy, or were receiving immunosuppressant agents.

The study was approved by the Institute of Review Board of each participating hospital, and a written informed consent was obtained from a parent/guardian of each subject. Upon inclusion, all medical records, including demographics, medical history, clinical signs and symptoms, diagnoses, and treatments of enrolled inpatients, were collected and kept in an electronic database.

Definition of alveolar pneumonia

Chest radiographs, obtained within 24 h of admission, were interpreted prospectively and independently by two pediatricians masked to patients’ clinical conditions. Pneumonia on a plain film was defined as a dense opacity with a fluffy consolidation of any size within a lobe, or the entire lung, with or without visible air bronchogram and pleural effusion. Two pediatricians, one of which a pediatric infectious disease specialist, interpreted the chest X rays independently and the diagnosis of CAP was confirmed if their interpretations agree.

Patients were grouped based on the radiological severity of alveolar pneumonia: 1) sub-lobar, 2) lobar, 3) with pleural effusion, 4) complicated pneumonia. Pleural effusion was defined as blunting of the costophrenic angle.13 Complicated pneumonia was defined as the presence of empyema or/and necrotizing pneumonia.14

Sample collection and processing

Blood samples, acute-phase serum specimens, and pleural fluids (if present; obtained by thoracentesis or thoracostomy) were collected after enrollment. Nasopharyngeal specimen was sampled using sterile swabs (Eswab; Copan Diagnostics Inc., Murrieta, Calif., USA). The swabs were introduced through a nostril and advanced until resistance was met. Following specimen collection, each swab was suspended in 1 ml of liquid Amies transport medium. A throat swab sample was obtained using a sterile nylon swab (Regular Flocked swab, Cat. No.520CS01, Copan Diagnostics Inc., Murrieta, Calif., USA) and placed in virus transport medium upon collection. Specimens were stored and transported at 4 °C to National Taiwan University Hospital for testing.

Bacterial study

Blood samples and pleural-fluid specimens were submitted for bacterial culture at each study site and processed according to standard techniques. Urinary S. pneumoniae antigens were detected using immunochromatographic tests (Binax NOW, Portland, Oregon, USA). A positive urine pneumococcal antigen test (Binax NOW) in children with CAP was considered a probable case of pneumococcal pneumonia.10 Real-time polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) assays targeting the S. pneumoniae lytA gene were performed on pleural fluid.13 Detection of Chlamydophila pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae were performed by PCR on nasopharyngeal swabs as previously described.15 , 16 Serum samples were tested for the presence of M. pneumoniae antibodies by using the IgM-specific Mycoplasma Immuno-Card, an enzyme immunoassay purchased from Meridian Bioscience (Cincinnati, OH), and the Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgG/IgM Antibody Test System (FTI-SERODIA-myco II test; Fujirebio Inc., Taipei, Taiwan) per manufacturers’ instructions. M. pneumoniae infection was confirmed if any following was present: (1) seropositivity of mycoplasma IgM in acute stage, (2) positive detection of M. pneumoniae in nasopharyngeal swab by PCR, or (3) four-fold or greater increase in the mycoplasma IgG titer in the acute stage and convalescent stage.

Detection of respiratory viruses

All nasopharyngeal swabs were subjected for viral isolation, including the followings (performed at each study site): fluorescent immunoassay for the detection of influenza A/B and RSV; and viral culture, with the cell lines usually including MK2, MRC-5, and MDCK cells. Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) was performed at the central laboratory to detect viruses of interest as follow: 200 uL of virus transport medium was placed in a MagNA Pure Compact instrument for automated nucleic acid extraction using MagNA Pure Compact Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit I (Roche Applied Science). The resulting RNA was reversely transcribed into cDNA using Transcriptor Reverse Transcriptase (Roche Applied Science) at National Taiwan University Hospital, and the cDNA sample was then sent to the Centers for Diseases Control of Taiwan (central laboratory) where multiplex real-time PCR was performed for detection of viruses, including adenovirus, coronavirus (229E, HKU1, OC43 and NL63), enterovirus, human metapneumovirus, influenza virus (types A and B), parainfluenza virus (types 1–3, 4A, and 4B), RSV, rhinovirus, bocavirus, polyomavirus, parechovirus, parvovirus, and human herpes virus 7.17 , 18

Statistical analyses

The National Health Insurance (NHI) program, which was initiated in 1995 by the government, covers 99.6% of Taiwan's population and 93% of the country's hospitals and clinics are NHI-contracted. The eight participating medical centers are established, long standing hospitals in the northern, middle and southern part of Taiwan and together serviced nearly 20% of the population covered by NHI.19 The annual incidence rates of hospitalization for CAP were calculated from January 2011 to December 2011, and from January 2012 to December 2012. The study intended to enroll at least 60% of children with CAP at each site. The actual number of participants therefore were adjusted according to the numbers of eligible subjected at each site. The annual population was adjusted according to the proportion of served population at each study site for the corresponding year. Age-specific population was provided by the Department of Household Registration Affairs of the Interior Ministry.

Statistical comparisons of incidence rate were performed using Poisson distribution with 95% confidence intervals; 95% confidence intervals for which the upper and lower bounds did not include 0 were interpreted as statistically significant. The x2 test or Fisher's exact test was used to assess group differences in categorical variables. For continuous variables, Student's t test or One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All probabilities were 2-tailed. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

A total of 1032 children with CAP were enrolled during the study period. A total of 494 (47.9%) were male. Their age ranged from 6 weeks to 17.9 years with a median of 4.7 years. Of these, 94 (9.1%) were under 2 years of age, 611 (59.2%) were between 2 and 5 years, and 327 (31.7%) were above 5 years. The annual incidence rates of hospitalization for CAP in children under 18 years in Taiwan was 69.5 cases per 100,000 population. The annual incidence rates by age was highest in children aged 2–5 years (229.7 cases per 100,000 population), followed by children aged < 2 years (69.8/100,000) and was lowest in children aged > 5 years (30.5/100,000).

Among the participants, 69 (6.7%) children had an underlying condition, including chromosome anomaly, metabolic disease, neurologic disorder, congenital heart disease, and hematologic disorder. A potential pathogen was identified in 705 (68.3%) of the 1032 children (Table 1 ). Isolated bacterial infection was detected in 420 (40.7%) children, isolated viral infection in 180 (17.4%), and viral-bacterial co-infection in 105 (10.2%). Bacterial infection (43.4%) was the most common cause of CAP in children aged 2–5 years, and viral infections (31.9%) in children under 2 years old, whereas the majority (42.8%) of CAP in children older than 5 years old had no identifiable pathogens (Table 1).

Table 1.

Etiologic identification of case with community-acquired pneumonia in each age group.

| Etiology | Total, N (%) | <2 yr | 2–5 yr | >5 yr | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 1032) | (n = 94) | (n = 611) | (n = 327) | ||

| Negative | 327 (31.7%) | 29 (30.9%) | 158 (25.9%) | 140 (42.8%) | <0.001 |

| Bacteria alone | 420 (40.7%) | 26 (27.7%) | 265 (43.4%) | 129 (39.4%) | 0.01 |

| S. pneumoniae | 326 (31.6%) | 28 (29.8%) | 257 (42.1%) | 41 (12.5%) | <0.001 |

| Urine antigen only | 270 (26.2%) | 22 (23.4%) | 210 (34.4%) | 38 (11.6%) | |

| Culture/PCR | 56 (5.4%) | 6 (6.4%) | 47 (7.7%) | 3 (0.9%) | |

| Blood | 28 (2.7%) | 4 (4.2%) | 22 (3.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | |

| Pleural fluid | 25 (2.4%) | 1 (1.1%) | 23 (3.8%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Blood and Pleural fluid | 3 (0.3%) | 1 (1.1%) | 2 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| M. pneumoniae | 233 (22.6%) | 6 (6.4%) | 115 (18.8%) | 112 (34.3%) | <0.001 |

| Throat PCR | 93 (9%) | 6 (6.4%) | 33 (5.4%) | 54 (16.5%) | |

| Serology | 108 (10.5%) | 0 (0%) | 69 (11.3%) | 39 (11.9%) | |

| PCR and serology | 32 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (2.1%) | 19 (5.9%) | |

| Virus alone | 180 (17.4%) | 30 (31.9%) | 115 (18.8%) | 35 (10.7%) | <0.001 |

| Mixed virus-bacteria | 105 (10.2%) | 9 (9.6%) | 73 (11.9%) | 23 (7%) | 0.06 |

The mean duration of hospitalization was 8.4 days (range: 1–84 days). A total of 377 (36.5%) children received supplemental oxygen therapy, and 246 (23.8%) children required intensive care. Children with CAP pathogens identified were younger (median, 4.5 years old vs. 5.3 years old, P < 0.001), and had longer hospital stay (mean, 9.3 days vs 6.5 days, P < 0.001), higher serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level (mean, 15.3 mg/dL vs. 11.4 mg/dL, P < 0.001), higher ICU admission rate (28.6% vs 13.7%, P < 0.001), and higher rate of O2 supplementation (41.2% vs 26.5%, P < 0.001) (Table 2 ). Pathogens were also more likely to be isolated in children with complicated pneumonia than those with lobar pneumonia (88.9% vs 64.6%, P < 0.001) (Table 2). Patients required intensive care were younger (median, 5.0 years old vs. 5.8 years old, P = 0.001), and had higher serum CRP level (mean, 22.2 mg/dL vs. 11.5 mg/dL, P < 0.001), longer hospital stays (mean, 17.2 days vs 5.7 days, P < 0.001), and higher rates of O2 supplementation (82.9% vs 22%, P < 0.001). ICU admission rates were also higher among cases with pleural effusion, complicated pneumonia, bacterial infection, and mixed viral-bacterial infection (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparisons of 1032 cases with community-acquired pneumonia based on etiology identification and ICU admission.

| Characteristic | Positive∗ (n = 705) | Negative∗ (n = 327) | P value | ICU (n = 246) | No ICU (n = 786) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 4.5 (0–17.9) | 5.3 (0–17.9) | <0.001 | 5.0 (0.1–17.7) | 5.8 (0–17.9) | 0.001 |

| Male | 344 (48.9) | 150 (45.7) | 0.3 | 125 (50.8) | 369 (46.9) | 0.3 |

| Prematurity | 80 (11.9) | 31 (9.5) | 0.2 | 25 (10.2) | 90 (11.5) | 0.6 |

| Underlying diseases | 36 (5.1) | 33 (10.1) | 0.003 | 22 (8.9) | 47 (6.0) | 0.1 |

| Mean CRP, mg/dL | 15.3 ± 12.7 | 11.4 ± 10.8 | <0.001 | 22.2 ± 12.8 | 11.5 ± 10.9 | <0.001 |

| CRP> 4 | 538 (76.4) | 216 (65.9) | <0.001 | 219 (89.0) | 535 (68.1) | <0.001 |

| CRP>10 | 401 (57.0) | 142 (43.3) | <0.001 | 195 (79.3) | 348 (44.3) | <0.001 |

| Length of Stay, days | 9.3 ± 9.3 | 6.5 ± 6.4 | <0.001 | 17.2 ± 12.7 | 5.7 ± 3.9 | <0.001 |

| ICU admission | 201 (28.6) | 45 (13.7) | <0.001 | – | – | – |

| O2 supply | 290 (41.2) | 87 (26.5) | <0.001 | 204 (82.9) | 173 (22.0) | <0.001 |

| Chest radiograph | ||||||

| Sublobar | 177 (25.1) | 94 (28.7) | 0.2 | 27 (11.0) | 244 (31.0) | <0.001 |

| lobar | 336 (47.7) | 184 (56.1) | 0.01 | 57 (23.2) | 463 (58.9) | <0.001 |

| With pleural effusion | 92 (13.1) | 37 (11.3) | 0.4 | 69 (28.0) | 60 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| Complicated pneumonia | 96 (13.6) | 12 (3.7) | <0.001 | 93 (37.8) | 15 (91.9) | <0.001 |

| Etiology | ||||||

| Virus alone | – | – | – | 47 (19.1) | 151 (19.2) | 1.0 |

| Bacteria alone | – | – | – | 123 (50.0) | 316 (40.2) | 0.008 |

| Mixed virus and bacteria | – | – | – | 34 (13.8) | 53 (6.7) | 0.001 |

∗Positive: cases with identified any potential pathogens, Negative: cases with no identified potential pathogen.

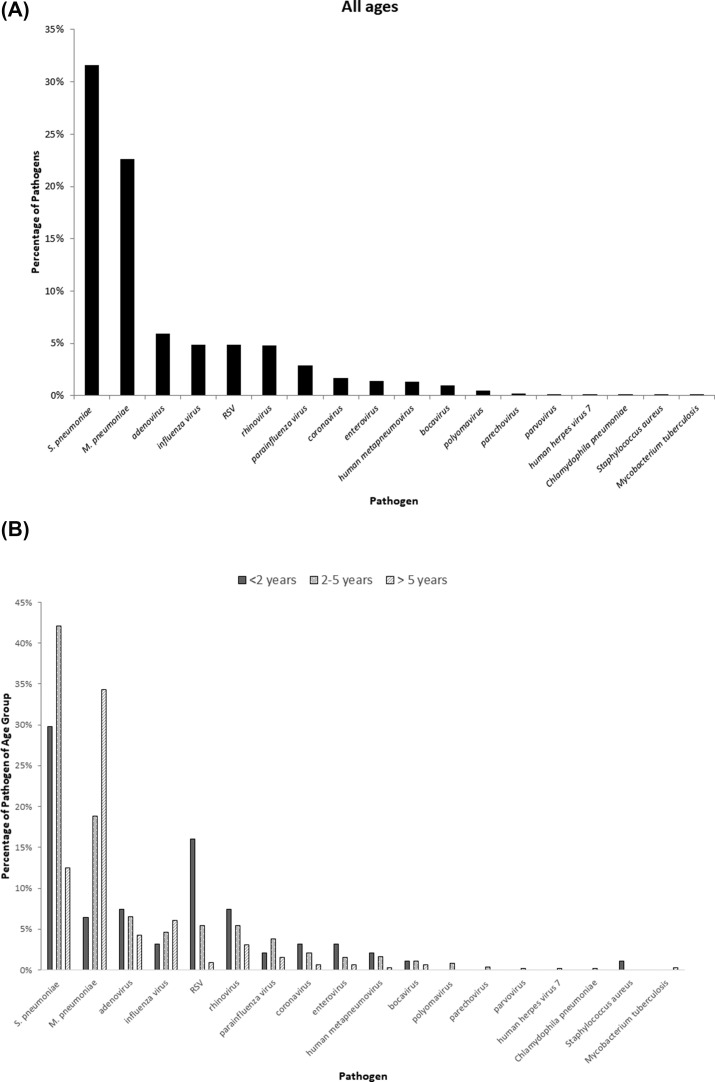

The most identified pathogen was 326 S. pneumoniae (31.6%). 56 patients had culture or PCR-confirmed pneumococcal pneumonia and the remaining 276 patients were probable pneumococcal pneumonia. Among the confirmed patients, serotype 19A were identified in 35 patients, serotype 3 in 5 patients, serotype 6A in 3 patients, serotype 19F, 6B, 14 in 2 patients; serotype 23F in 1 patient and unknown in 6 patients. Other pathogens identified were 233 M. pneumoniae (22.6%), 61 adenovirus (5.9%), 51 influenza virus (4.9%), 51 RSV (4.9%), 50 rhinovirus (4.8%), and 30 parainfluenza virus (2.9%) (Fig. 1 A).

Figure 1.

(A) Pathogens identified in our study. (B) Percentages of each pathogen in different age groups. RSV: respiratory syncytial virus.

The pathogens exhibited age-specific patterns. RSV was significantly associated with children aged under 2 years (P < 0.001), S. pneumoniae in children aged between 2 and 5 years (P < 0.001), and M. pneumoniae in children aged >5 years (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). Pneumonia caused by S. pneumoniae was significantly associated with leukocytosis, high C-reactive protein and complicated pneumonia compared to those caused by M. pneumoniae and virus alone (P < 0.001) (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Comparisons of cases with community-acquired pneumonia based on different etiology.

| Characteristic | S. pneumoniae (n = 326) | M. pneumoniae (n = 233) | Virus alone (n = 180) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 4.2 (0–17.7) | 6.8 (0.5–17.9) | 3.9 (0.2–17.6) | <0.001 |

| Male | 172 (52.89) | 91 (46.2) | 81 (45) | 0.2 |

| Fever | 282 (86.5) | 156 (79.2) | 149 (82.8) | 0.09 |

| Cough | 315 (96.6) | 193 (98) | 171 (95) | 0.3 |

| Abdominal pain | 217 (66.6) | 141 (71.6) | 117 (65) | 0.3 |

| Mean white blood cell count (x103/uL) | 15.1 ± 5.9 | 8.9 ± 3.9 | 11 ± 5.6 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin level, g/dL | 10.5 ± 4.6 | 11.9 ± 1.3 | 11.4 ± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Mean CRP, mg/dL | 22 2 ± 12.4 | 7.9 ± 7.9 | 11 ± 11 | <0.001 |

| CRP> 4 | 299 (91.7) | 115 (58.4) | 57 (68.3) | <0.001 |

| CRP>10 | 267 (81.9) | 55 (27.9) | 78 (43.3) | <0.001 |

| Chest radiograph | ||||

| Sublobar | 49 (15) | 142 (27.9) | 73 (40.6) | <0.001 |

| lobar | 134 (41.1) | 123 (62.4) | 79 (43.9) | <0.001 |

| With pleural effusion | 51 (15.6) | 17 (8.6) | 23 (12.8) | 0.07 |

| Complicated pneumonia | 89 (27.3) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.8) | <0.001 |

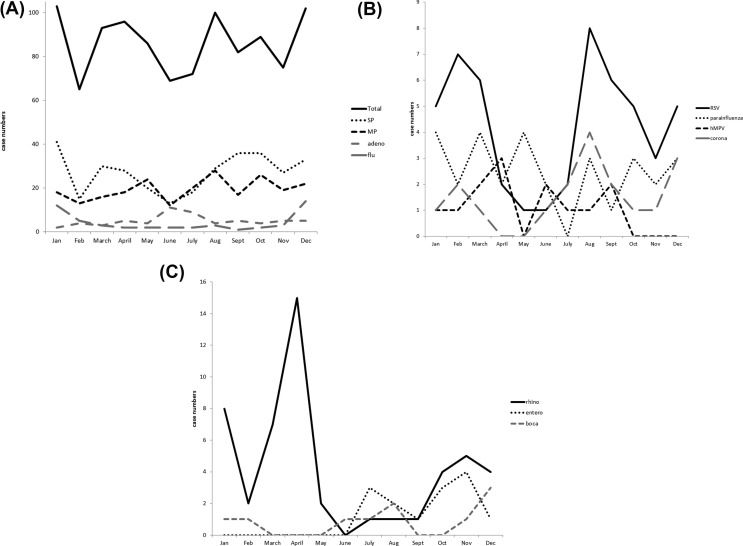

Pneumonia was reported in all months of the year. S. pneumoniae CAP occurred year-round, but incidence was lower from May to July (Fig. 2 A). M. pneumoniae was also detected year-round, but the incidence was lower from February to April (Fig. 2A). Influenza related CAP peaked in the winter season whereas adenovirus related CAP was more frequently seen in June and July (Fig. 2A). RSV was detected year-round but had bimodal peaks in February to March and August to September (Fig. 2B). Rhinovirus peaked in April (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Case numbers of pathogen detection in each month during November 2010 to September 2013. (A) Total pathogens, SP, MP, adeno, and flu; (B) RSV, parainfluenza, hMPV, corona; (C) rhino, entero, and boca. SP: S. pneumoniae, MP: M. pneumoniae, adeno: adenovirus, and flu: influenza virus, RSV: respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza: parainfluenza virus hMPV: human metapneumovirus, corona: coronavirus, rhino: rhinovirus, entero: enterovirus, and boca: bocavirus.

Adenovirus, influenza virus, rhinovirus, parainfluenza virus, coronavirus, enterovirus, polyomavirus, parechovirus, S. pneumoniae, and M. pneumoniae were more likely to be present with other pathogens (Table 4 ). M. pneumoniae, rhinovirus, and influenza virus were frequently isolated with S. pneumoniae and adenovirus frequently with M. pneumoniae (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of various pathogens in 705 patients with community-acquired pneumonia.

| Pathogen (No.) | Single infection (n = 550) No. (%) |

Mixed infection (n = 155) No. (%) |

P value | Mixed with |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other viruses (No.) | S. pneumoniae (No.) | M. pneumoniae (No.) | ||||

| Adenovirus (61) | 35 (6.4) | 26 (16.8) | <0.001 | 11 | 7 | 13 |

| Influenza (51) | 27 (4.9) | 24 (15.5) | <0.001 | 3 | 17 | 7 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus (51) | 40 (7.3) | 11 (7.1) | 1.0 | 4 | 7 | 2 |

| Rhinovirus (50) | 22 (4.0) | 28 (18.1) | <0.001 | 6 | 18 | 4 |

| Parainfluenza (30) | 15 (2.7) | 15 (9.7) | 0.002 | 7 | 8 | 4 |

| Coronavirus (18) | 5 (0.9) | 13 (8.4) | <0.001 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Enterovirus (14) | 3 (0.5) | 11 (7.1) | <0.001 | 4 | 7 | 3 |

| Human metapneumovirus (13) | 9 (1.6) | 4 (2.6) | 0.5 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Bocavirus (10) | 6 (1.0) | 4 (2.6) | 0.2 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Polyomavirus (5) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (2.6) | 0.009 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Parechovirus (2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) | 0.05 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Parvovirus (1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Human herpes virus 7 (1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae (1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (326) | 221 (40.3) | 105 (67.7) | <0.001 | 73 | – | 36 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae (233) | 164 (29.7) | 69 (44.5) | 0.002 | 37 | 36 | – |

| Staphylococcus aureus (1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | – | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis (1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | – | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 5 showed the Annual incidence of hospitalized childhood CAP between 2011 and 2012. From 2011 to 2012, a significant reduction in CAP hospitalization rates pertained to children aged under 5 years of age. Pneumococcal pneumonia related hospitalization rated decreased by 37% (95% CI: −52% to −18%) in 2012. Pneumonia secondary to mixed virus-bacterial infections (−43%; 95% CI: −63% to −12%) also had decreased. Pneumonia needs ICU admission (−35%; 95% CI: −52% to −12%), sublobar pneumonia (−18%; 95% CI: −33%–1%), pneumonia with pleural effusion (−37%; 95% CI: −58% to −5%) and complicated pneumonia (−63%; 95% CI: −77% to −40%) had also significantly decreased. Hospitalization rates for adenovirus pneumonia and viral pneumonia were high in 2011 but had decreased by 83% (95% CI: −91% to −65%) and 56% (95% CI: −70% to −37%) in 2012, respectively.

Table 5.

Annual incidence of hospitalized childhood community-acquired pneumonia between 2011 and 2012.

| Characteristics | Incidence (no. of cases per 100,000 children per year) |

Relative Changes in Incidence (2011 vs 2012) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 2011 | 2012 | Percentage (95% CI) | P value | |

| Total | 69.5 | 78.5 | 60.3 | −30 (−40 to −20) | <0.001 |

| Age group (year-old) | |||||

| <2 | 69.8 | 93.5 | 49.6 | −47 (−68 to −12) | 0.01 |

| 2-5 | 229.7 | 270.3 | 187.1 | −31 (−43 to −16) | <0.001 |

| >5 | 30.5 | 30.0 | 31.1 | 3.6 (−20 to 33.6) | 0.8 |

| Pathogen | |||||

| S. pneumoniae | 21.4 | 25.2 | 17.5 | −37 (−52 to −18) | 0.001 |

| M. pneumoniae | 15.6 | 16.6 | 14.6 | −20 (−41 to 8) | 0.2 |

| Adenovirus | 5.4 | 8.9 | 1.7 | −83 (−91 to −65) | <0.001 |

| Influenza | 4.2 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 15.3 (−36 to 107) | 0.6 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 3.0 | 3.4 | 2.7 | −28 (−64 to 44) | 0.4 |

| Parainfluenza | 2.3 | 2.8 | 1.7 | −45 (−76 to 27) | 0.16 |

| Human metapneumovirus | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.6 | −60 (−90 to 53) | 0.2 |

| Virus-bacteria coinfection | 8.4 | 10.3 | 6.5 | −43 (−63 to −12) | 0.01 |

| Requiring ICU admission | 18.1 | 25.4 | 10.6 | −67 (−72 to −48) | <0.001 |

| Sublobar pneumonia | 16.4 | 19.0 | 13.7 | −35 (−52 to −12) | 0.005 |

| Lobar pneumonia | 36.3 | 38.0 | 34.6 | −18 (−33 to 1) | 0.06 |

| Pneumonia with pleural effusion | 9.0 | 10.6 | 7.4 | −37 (−58 to −5) | 0.02 |

| Complicated pneumonia | 7.5 | 10.7 | 4.4 | −63 (−77 to −40) | <0.001 |

Discussion

The hospitalization rate for CAP under 18 years of age in this study was 69.5 cases per 100,000 population, which was 30%–40% lower than that of the United States (157–225 cases per 100,000 population).8 , 20 The incidence rates in this study was lower because we intended to recruit only cases with radiologically-confirmed pneumonia including sub-lobar, lobar, with pleural effusion, or complicated pneumonia. The incidences for complicated pneumonia including empyema, necrotizing pneumonia, were otherwise similar in both countries (4.4–10.7 cases vs. 5.4 to 9.6 cases per 100,000 population).20

In accordance with our expectations, S. pneumoniae was the leading cause of CAP in children under 5-year-old. Most of the pneumococcal infections were diagnosed via urinary antigen tests, but the specificity of the urinary Binax NOW assay in the diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia was variable.21 Literatures had correlated positive urinary antigen results to higher nasopharyngeal carriage rate of pneumococci.22 , 23 However, only 14.1% of Taiwanese children aged 2–60 months were colonized by pneumococci in the nasopharynx, a frequency that was much lower than other studies.24

In the present study, pneumococcus was documented to contribute to 31.6% of the CAP, similar to the incidence rates of 37–46% reported previously in Taiwan11 and other countries.25 , 26 The leading disease burden of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in Taiwan was bacteremic pneumonia/empyema in children aged between 2 and 5 years.27 Surveillance data from the CDC-Taiwan revealed that the incidence rate of IPD in children aged between 2 and 5 years had increased from 16.8 cases per 100,000 person-years in 2008–2010 to 22.8 cases per 100,000 person-years in 2011–2012.28 During this time of sub-optimal vaccination coverage of PCV, there were many children aged 2–4 years who suffered from severe pneumococcal pneumonia with empyema.29 , 30 The increase was attributed to the emergence and surge of serotype 19A during the studied time period.28, 29, 30 The emergence of serotype 19A was presumably why S. pneumoniae still stood out as the predominant pathogen in children with CAP in our study. The 13-valent PCV (PCV13) has been available in the private market in Taiwan since 2011. Within one year of optional PCV13 immunization, the annual CAP hospitalization rates had lowered in children under 5 years of age. The annual incidence rates of pneumococcal pneumonia and complicated pneumonia had also decreased by 30%–60% in 2012. Reduction in incidence rates of hospitalization was also observed in cases with mixed viral-bacterial CAP, which agreed with previous observations by Madhi et al.31 Our results provided valid evidence and demonstrated the critical role of S. pneumoniae in the development of virus-associated pneumonia. A national vaccination catch-up program providing 1 dose of PCV13 to children aged 2–5 years was launched in 2013, followed by a program providing 2 doses in children aged 1–2 years old in 2014 and a 2 + 1 national infant immunization program in 2015.32 Based on the surveillance data from the CDC-Taiwan, the incidence rate of IPD in children aged 2–5 years had decreased to 11.9/100,0000 person-years in 2013.28 The incidence rate of pneumococcal pneumonia is expected to continue falling under the current PCV13 immunization policy.

The current diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infections relies on serology or molecular diagnosis by using real-time PCR to detect bacterial DNA from respiratory samples. Studies have shown that M. pneumoniae was responsible for 8%–35% of CAP, confirmed either by serology and/or PCR.8 , 9 , 25 In the present study, diagnoses of mycoplasma infection were demonstrated from RT-PCR, serology, or both in 12.1%, 13.6%, and 3.1% of our cases (respectively). Spuesens et al.33 reported that M. pneumoniae is present in the upper respiratory tract in asymptomatic children and concluded the current diagnostic modalities are unable to differentiate symptomatic infection from asymptomatic carriage of M. pneumoniae. Furthermore, serological data do not correlate well with PCR results.33 Thus, it remains challenging to establish a definite diagnosis of mycoplasma infection.

Case-controlled studies exploring the causal relationship between pathogens and pneumonia, had associated RSV, influenza, hMPV, parainfluenza, adenovirus, and coronavirus with CAP, especially the first three.8 , 34 , 35 Self et al.35 demonstrated an age-dependent relationship between rhinovirus, adenovirus and CAP. Rhinovirus was associated with CAP in adults, but not in children. Adenovirus associated CAP occurred only in children aged under 2 years old. Geographical, seasonal, and epidemiological factors could have contributed to the apparent differences. In the present study, adenovirus was the most frequently detected virus in children with CAP. In 2011, Taiwan experienced a community outbreak of co-circulating adenovirus type 2, 3 and 7.36 Among the 203 cases of adenovirus infection identified at a tertiary center, 39% had consolidation on radiograph, 15.3% required intensive care, and 3.4% died.36 The outbreak was within the period of this study, which explains why adenovirus was the most common virus identified in this study.

It is worth mentioning that most of the studies have tested nasopharyngeal specimens using quantitative real-time PCR in CAP patients. Although highly sensitive, quantitative real-time PCR should be utilized cautiously. Viruses can often be isolated from the respiratory tracts. Given, rhinovirus, enterovirus, and bocavirus have been detected frequently in asymptomatic children, the clinical significance of PCR results should be interpreted carefully.8 , 37 A previous study from Taiwan reported that the viral detection rates among asymptomatic children in Taiwan were 9.7% (vs. 4.8% in the present study) for rhinovirus, 4.4% (vs. 1.4% in the present study) for enterovirus, and 0.9% (vs. 1.7% in the present study) for coronavirus, respectively.38 Influenza and hMPV were not detected in asymptomatic children in that study.38 Furthermore, the nasopharynx is distant from the lung; nasopharyngeal sampling is not representative of bronchopulmonary specimens.

The major drawbacks of the present study were (1) the lack of controls without pneumonia to assess the strength of association between a positive test and pneumonia etiology, (2) the use of positive urinary antigen test as the diagnosis of pneumococcal infection, which might be subjected to substantial over-diagnosis, and (3) the dearth of diagnostic tools with sensitivities sufficient to permit identification of bacterial sources of infection. The latter issue was presumably the reason for the relatively low detection rate of pathogens in our study. We might need an integrated analytic approach on studies of pneumonia etiology with different perspectives in the future. However, the strength of the present study is that this work was a prospective, multicenter study, that had spanned for 3 years, providing thorough inspections of CAP pathogens in different seasons.

In this study, we observed improved conjugated pneumococcal vaccination coverage was associated with reduction in the incidence rates of CAP secondary to S. pneumoniae, Adenovirus, and viral-bacterial coinfections. The implementation of PCV13 will render M. pneumoniae, adenovirus, influenza, RSV, parainfluenza and hMPV significant CAP agents. This study described the latest incidences and trends of CAP pathogens, which are crucial for prompt delivery of appropriate therapy.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the research staff and all the children and families who have participated in this study. This work was supported by a grant from National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan and two grants (grant CMRPG3F1871 and CMRPG3F1591 to YC Hsieh) from the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. We have no conflicts of interest to declare in connection with the present study.

References

- 1.Williams B.G., Gouws E., Boschi-Pinto C., Bryce J., Dye C. Estimates of world-wide distribution of child deaths from acute respiratory infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(01)00170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs331/en/

- 3.Bradley J.S., Byington C.L., Shah S.S., Alverson B., Carter E.R., Harrison C. Executive summary: the management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:617–630. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntosh K. Community-acquired pneumonia in children. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:429–437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y.C., Ho Y.H., Hsieh Y.C., Lin H.C., Hwang K.P., Chang L.Y. A 6-year retrospective epidemiologic study of pediatric pneumococcal pneumonia in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2008;107:945–951. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michelow I.C., Olsen K., Lozano J., Rollins N.K., Duffy L.B., Ziegler T. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:701–707. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf D.G., Greenberg D., Shemer-Avni Y., Givon-Lavi N., Bar-Ziv J., Dagan R. Association of human metapneumovirus with radiologically diagnosed community-acquired alveolar pneumonia in young children. J Pediatr. 2010;156:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain S., Williams D.J., Arnold S.R., Ampofo K., Bramley A.M., Reed C. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:835–845. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsolia M.N., Psarras S., Bossios A., Audi H., Paldanius M., Gourgiotis D. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized school-age children: evidence for high prevalence of viral infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:681–686. doi: 10.1086/422996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C.J., Lin P.Y., Tsai M.H., Huang C.G., Tsao K.C., Wong K.S. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children in northern Taiwan. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:e196–e201. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31826eb5a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsieh Y.C., Lin T.L., Chang K.Y., Huang Y.C., Chen C.J., Lin T.Y. Expansion and evolution of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 19A ST320 clone as compared to its ancestral clone, Taiwan19F-14 (ST236) J Infect Dis. 2013;208:203–210. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartlett J.G. Diagnostic tests for agents of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 4):S296–S304. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsieh Y.C., Chi H., Chang K.Y., Lai S.H., Mu J.J., Wong K.S. Increase in fitness of Streptococcus pneumoniae is associated with the severity of necrotizing pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:499–505. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh Y.C., Hsueh P.R., Lu C.Y., Lee P.I., Lee C.Y., Huang L.M. Clinical manifestations and molecular epidemiology of necrotizing pneumonia and empyema caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:830–835. doi: 10.1086/381974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luchsinger V., Ruiz M., Zunino E., Martinez M.A., Machado C., Piedra P.A. Community-acquired pneumonia in Chile: the clinical relevance in the detection of viruses and atypical bacteria. Thorax. 2013;68:1000–1006. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu P.S., Chang L.Y., Lin H.C., Chi H., Hsieh Y.C., Huang Y.C. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of children with macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in Taiwan. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48:904–911. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chidlow G.R., Harnett G.B., Shellam G.R., Smith D.W. An economical tandem multiplex real-time PCR technique for the detection of a comprehensive range of respiratory pathogens. Viruses. 2009;1:42–56. doi: 10.3390/v1010042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pretorius M.A., Madhi S.A., Cohen C., Naidoo D., Groome M., Moyes J. Respiratory viral coinfections identified by a 10-plex real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assay in patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory illness-South Africa, 2009-2010. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(Suppl 1):S159–S165. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Insurance MoHaWTHaNH, from Asisa. www.mohw.gov.tw/cht/DOS/Statistic.aspx?f_list_no=312h

- 20.Lee G.E., Lorch S.A., Sheffler-Collins S., Kronman M.P., Shah S.S. National hospitalization trends for pediatric pneumonia and associated complications. Pediatrics. 2010;126:204–213. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen C.F., Wang S.M., Liu C.C. A new urinary antigen test score correlates with severity of pneumococcal pneumonia in children. J Formos Med Assoc. 2011;110:613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adegbola R.A., Obaro S.K., Biney E., Greenwood B.M. Evaluation of Binax now Streptococcus pneumoniae urinary antigen test in children in a community with a high carriage rate of pneumococcus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:718–719. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200107000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dowell S.F., Garman R.L., Liu G., Levine O.S., Yang Y.H. Evaluation of Binax NOW, an assay for the detection of pneumococcal antigen in urine samples, performed among pediatric patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:824–825. doi: 10.1086/319205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen C.J., Huang Y.C., Su L.H., Lin T.Y. Nasal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in healthy children and adults in northern Taiwan. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michelow I.C., Lozano J., Olsen K., Goto C., Rollins N.K., Ghaffar F. Diagnosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae lower respiratory infection in hospitalized children by culture, polymerase chain reaction, serological testing, and urinary antigen detection. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E1–E11. doi: 10.1086/324358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vuori E., Peltola H., Kallio M.J., Leinonen M., Hedman K. Etiology of pneumonia and other common childhood infections requiring hospitalization and parenteral antimicrobial therapy. SE-TU study group. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:566–572. doi: 10.1086/514697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsieh Y.C., Lin P.Y., Chiu C.H., Huang Y.C., Chang K.Y., Liao C.H. National survey of invasive pneumococcal diseases in Taiwan under partial PCV7 vaccination in 2007: emergence of serotype 19A with high invasive potential. Vaccine. 2009;27:5513–5518. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei S.H., Chiang C.S., Chiu C.H., Chou P., Lin T.Y. Pediatric invasive pneumococcal disease in Taiwan following a national catch-up program with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:e71–e77. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin T.Y., Hwang K.P., Liu C.C., Tang R.B., Lin C.Y., Gilbert G.L. Etiology of empyema thoracis and parapneumonic pleural effusion in Taiwanese children and adolescents younger than 18 years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:419–421. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31828637b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu C.Y., Ting Y.T., Huang L.M. Severe Streptococcus pneumoniae 19A pneumonia with empyema in children vaccinated with pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. J Formos Med Assoc. 2015;114:783–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madhi S.A., Klugman K.P. A role for Streptococcus pneumoniae in virus-associated pneumonia. Nat Med. 2004;10:811–813. doi: 10.1038/nm1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su W.J., Lo H.Y., Chang C.H., Chang L.Y., Chiu C.H., Lee P.I. Effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines of different valences against invasive pneumococcal disease among children in Taiwan: a nationwide study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35:e124–e133. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spuesens E.B., Fraaij P.L., Visser E.G., Hoogenboezem T., Hop W.C., van Adrichem L.N. Carriage of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the upper respiratory tract of symptomatic and asymptomatic children: an observational study. PLoS Med. 2013;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhedin S., Lindstrand A., Hjelmgren A., Ryd-Rinder M., Ohrmalm L., Tolfvenstam T. Respiratory viruses associated with community-acquired pneumonia in children: matched case-control study. Thorax. 2015;70:847–853. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Self W.H., Williams D.J., Zhu Y., Ampofo K., Pavia A.T., Chappell J.D. Respiratory viral detection in children and adults: comparing asymptomatic controls and patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:584–591. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsou T.P., Tan B.F., Chang H.Y., Chen W.C., Huang Y.P., Lai C.Y. Community outbreak of adenovirus, Taiwan, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1825–1832. doi: 10.3201/eid1811.120629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhedin S., Lindstrand A., Rotzen-Ostlund M., Tolfvenstam T., Ohrmalm L., Rinder M.R. Clinical utility of PCR for common viruses in acute respiratory illness. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e538–e545. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang L.Y., Lu C.Y., Shao P.L., Lee P.I., Lin M.T., Fan T.Y. Viral infections associated with Kawasaki disease. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]