Abstract

Background

Despite calls to study how healthcare providers’ emotions may impact patient safety, little research has addressed this topic. The current study aimed to develop a comprehensive understanding of emergency department (ED) providers’ emotional experiences, including what triggers their emotions, the perceived effects of emotions on clinical decision making and patient care, and strategies providers use to manage their emotions to reduce patient safety risks.

Methods

Employing grounded theory, we conducted 86 semi-structured qualitative interviews with experienced ED providers (45 physicians and 41 nurses) from four academic medical centres and four community hospitals in the Northeastern USA. Constant comparative analysis was used to develop a grounded model of provider emotions and patient safety in the ED.

Results

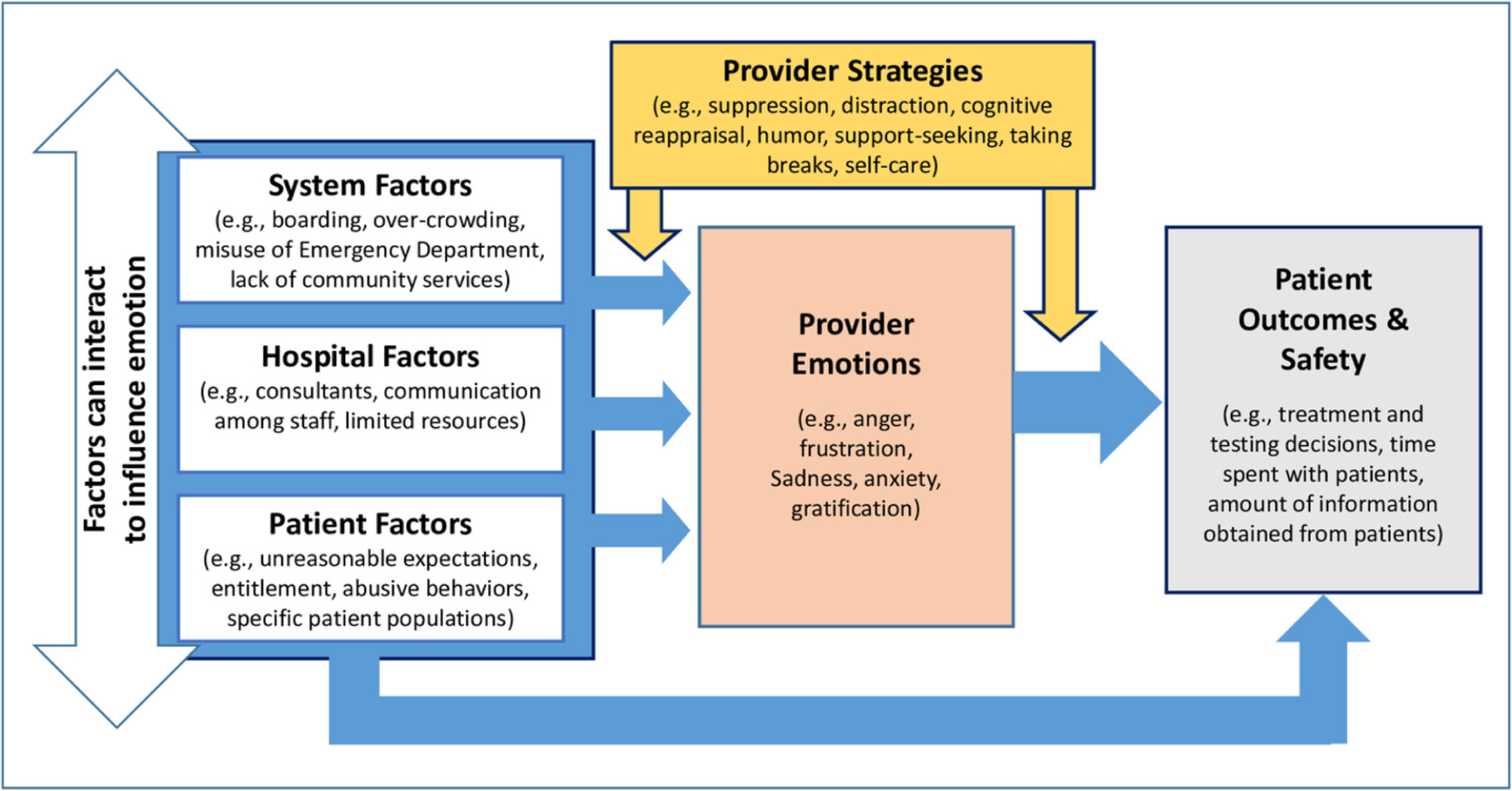

ED providers reported experiencing a wide range of emotions in response to patient, hospital, and system-level factors. Patients triggered both positive and negative emotions; hospital and system-level factors largely triggered negative emotions. Providers expressed awareness of possible adverse effects of negative emotions on clinical decision making, highlighting concerns about patient safety. Providers described strategies they employ to regulate their emotions, including emotional suppression, distraction, and cognitive reappraisal. Many providers believed that these strategies effectively guarded against the risk of emotions negatively influencing their clinical decision making.

Conclusion

The role of emotions in patient safety is in its early stages and many opportunities exist for researchers, educators, and clinicians to further address this important issue. Our findings highlight the need for future work to (1) determine whether providers’ emotion regulation strategies are effective at mitigating patient safety risk, (2) incorporate emotional intelligence training into healthcare education, and (3) shift the cultural norms in medicine to support meaningful discourse around emotions.

INTRODUCTION

Emergency departments (EDs) in the USA manage over 140 million patient visits each year, a number that has grown significantly in recent years.1 EDs treat a wide range of patients, from the critically ill to those with relatively minor health concerns, and those with unmet social needs. The ED poses unique challenges for providers due to the high variability and volume of patients, lack of pre-existing relationships with patients, highly unpredictable conditions, frequent interruptions, and limited resources, among other factors.2, 3 In the USA, these challenges are magnified by the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labour Act, an unfunded mandate enacted by Congress over 30 years ago requiring EDs to provide medical assessment and treatment for all patients, regardless of medical complaint or ability to pay.4 Thus, for many reasons, the ED can be an emotional and stressful environment where patient safety risks and diagnostic errors are heightened.5–7

Research in affective and social cognitive science unequivocally demonstrates that emotions can profoundly influence information processing, decision making, and behaviour.8–11 Despite this, emotions have generally been overlooked in the practice of medicine, which has traditionally been viewed as driven by cold, rational, cognitive processes.12–14 Although several scholars have raised concerns that providers’ emotions may adversely impact clinical decision making and patient safety,12, 13, 15–17 and some have considered risks for patients described as ‘hateful’18 or ‘difficult’,19–21 no comprehensive study has been conducted that focuses explicitly on triggers and consequences of providers’ emotions.

Several noteworthy publications have brought attention to the role of provider emotions in patient safety. For example, Croskerry and colleagues16, 17 reviewed literature across multiple disciplines and catalogued factors that may influence providers’ emotions and clinical decision making. More recently, Kozlowski et al13 synthesised results from 23 studies related to this topic; however, only 5 studies focused specifically on both emotions and clinical decision making. Moreover, none of the studies involved ED providers or directly investigated strategies providers use to regulate their emotions, and many were conducted in narrow clinical contexts (eg, end of life care and older adult nursing care).

Despite some progress reflected in this recent work, knowledge gained from integrative reviews is limited by the available research22 and, as the Kozlowski et al13 review demonstrates, published work on emotions and patient safety is somewhat fragmented. The current research aimed to address this gap by investigating the following questions: (1) What emotions do providers feel while working in the ED and what triggers these emotions? (2) How do these emotions impact clinical decision making and patient care? (3) What strategies do ED providers use to manage their emotions? In examining these questions, we offer the first data-driven model of the antecedents and consequences of providers’ emotions in the ED.

METHODS

Using grounded theory,23, 24 we conducted semi-structured interviews with 86 ED providers (45 physicians and 41 nurses) in the Northeastern USA between February and August 2018. Providers were asked about their emotions, emotional triggers, beliefs about emotional influences on patient safety, and emotion management strategies (see online supplementary file for interview topic guide). Interview topics and questions were developed based on a pilot interview study with 25 ED providers (15 physicians and 10 nurses) conducted between July 2016 and April 2017. Except for one telephone interview, all interviews were conducted face-to-face in private settings by LMI, an experienced psychology researcher. Memos and expert debriefing were used to enhance interviewer reflexivity. Interviews lasted 45–90 min; most lasted approximately 65 min. Consistent with the average hourly rate for ED physicians in the USA at the time,25 physicians received US$250 compensation for their participation. Nurses received US$100.

Sampling and recruitment

Administrators at four academic medical centres shared our recruitment materials via email with possible participants. The study was described as ‘a federally funded project designed to help us gain a better understanding of the factors that impact clinical reasoning and decision making in emergency medicine’. Email recipients were informed that if they participated, they would be asked about their experiences working as an ED provider. No additional information was given.

We used theoretic sampling throughout recruitment, seeking participants with a variety of roles, administrative positions, experiences, and demographics. In grounded theory research, sample size is determined based on achieving theoretical saturation and cannot be determined with certainty a priori23; however, 20–30 participants typically yield saturation.26 We oversampled to ensure we could compare physicians and nurses across different contexts and to ensure we recruited a diverse sample of providers with different levels of experience. After noting potential contextual effects at four academic hospitals, we extended recruitment to four community hospitals to build transferability. We then conducted interviews until we again achieved saturation.

The hospitals that participated are well-established institutions. The academic hospitals have major trauma centres, are located in large cities, serve diverse patient populations, and train medical students and residents. Three of the community hospitals are located in suburban areas, and one is located in a large city; all serve diverse populations. The community hospital sample includes physicians recruited directly from four community hospitals and nurses from two of these hospitals. Some physicians recruited from academic hospitals also worked at community hospitals within the same healthcare system. To our knowledge, there were no recent initiatives at any of these hospitals that may have affected morale within the ED.

Data analysis

Digital interview recordings were transcribed verbatim by undergraduate research assistants. Two additional research assistants reviewed each transcript for accuracy. Using NVivo V.11, HC, GL and EC independently coded five initial transcripts and met to resolve discrepancies. Thereafter, HC and GL used a shared codebook to code transcripts, which EC reviewed for consistency. They resolved discrepancies and developed new codes via regular meetings and email conversations. The coding process followed constant comparative analysis guidelines commonly used in grounded theory24, 27: after open coding, we developed axial codes and then used these axial codes to support selective coding (see online supplementary file for additional details).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 contain participant information.

Table 1.

Participant samples recruited from different hospitals

| Physicians | Nurses | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital A | 13 | 7 | 20 |

| Hospital B | 10 | 7 | 17 |

| Hospital C | 8 | 7 | 15 |

| Hospital D | 7 | 8 | 15 |

| Community hospitals | 7 | 12 | 19 |

| Total | 45 | 41 | 86 |

Note: Hospitals A–D are academic medical centres.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics

| Physicians | Nurses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 45 | 41 | ||

| Mean age (SD) | 40 (7.95) | 39.12 (11.13) | ||

| Range (median) | 29–63 (37) | 26–65 (36) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 33 (74) | 7 (17) | ||

| Female | 12 (27) | 34 (72) | ||

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 32 (71) | 37 (90) | ||

| Hispanic | 2 (4) | 2 (5) | ||

| Asian/Indian | 8 (18) | - | ||

| Black | - | 1 (2) | ||

| Biracial/other | 3 (7) | - | ||

| Missing data | - | 1 (2) | ||

| Years of experience overall (as physician or nurse) (SD) | 8.58 (7.38) | 13.27 (11.06) | ||

| Range (median) | 0.5–32.0 (6.00) | 1–43 (8.00) | ||

| Years of experience in ED at current institution (SD) | 7.54 (5.74) | 8.17 (9.06) | ||

| Range (Median) | 0.5–25.0 (6.00) | 0.5–33.0 (3.50) | ||

| Leadership positions, n (%) | 24 (53) | 10 (24) | ||

| Chief/chair of ED | 4 (9) | - | ||

| Vice Chief/chair of ED | 2 (4) | - | ||

| Medical clinical director | 4 (9) | - | ||

| Assistant clinical director | 1 (2) | - | ||

| Other directors | ||||

| Ultrasound, infomatics, other | 3 (7) | - | ||

| Patient experience and provider engagement | 1 (2) | |||

| Education and training | ||||

| Director of clinical education | 2 (4) | |||

| Fellowship director | 3 (7) | - | ||

| Assistant residency director | 3 (7) | - | ||

| Assistant chief quality officer | 1 (2) | - | ||

| Charge nurse (current) | - | 4 (10) | ||

| Charge nurse (former) | - | 2 (5) | ||

| Nurse manager | - | 1 (2) | ||

| Assistant nurse manager | - | 1 (2) | ||

| Director of ED | - | 2 (5) | ||

ED, emergency department.

Grounded model of provider emotions and patient safety

Figure 1 presents a grounded model of provider emotions and patient safety constructed from our data. This model includes emotion-eliciting factors in the ED, effects of provider emotions on patient safety, and emotion regulation strategies that providers employ in an effort to reduce adverse influences of emotions on patient safety. Each aspect of this model is described further with exemplar quotes. Additional quotes appear in the online supplementary file.

Figure 1.

Grounded model of provider emotions and patient safety in the emergency department.

Patient, hospital, and system-level causes of provider emotions

Providers reported experiencing a wide range of both negative and positive emotions in the ED, including pride, guilt, fear and happiness; however, providers most frequently mentioned experiencing frustration, anger, sadness, and gratification. They emphasised the emotionally challenging nature of the ED and reported experiencing emotions in response to three main triggers: patient, hospital, and system-level factors.

Patient factors

Frustration, sadness, and gratification were common emotional responses to patients. There was considerable consensus in the patient factors that elicited frustration and anger: unrealistic expectations, entitlement, and other challenging behaviours and patient populations detailed further.

Providers perceived a lack of public understanding of the purpose of the ED, which results in unrealistic expectations that cause frustration for both patients and providers. For example, many people go to the ED in the hopes of solving a chronic, long-standing problem. Yet, as one physician (54) stated,

While we certainly would like to be answering the question ‘what is this?’ most of the time the way we come at it is ‘what does this have to not be?

Providers discussed difficulty in setting and managing patient expectations. One physician (14) articulated,

… the challenge is how do I reset those expectations in a way that the patient leaves feeling satisfied, even though I wasn’t able to meet their expectations?

Providers also perceived entitlement among some patients, which prompted frustration and anger. Demanding patients and family members who were perceived as failing to recognise providers’ competing priorities were representative of entitlement. One physician (64) noted:

I remember one woman who specifically said, ‘I don’t care if someone else is having a stroke’… When patients acknowledge there are horrible things going on and they just don’t care because they think they’re more important, that makes me pretty angry.

Abuse of the ED system or personnel was also seen as a form of entitlement. For example, participants described feeling angry in response to patients who lied about chest pain to receive faster service or who came in merely to get a note for work. Providers also recounted experiences with patients who were verbally and sometimes physically abusive. One physician (69) stated:

I’ve been hit, kicked, punched…yelled at and screamed and sworn at…that’s hard too, you know, when you’re trying to do the right thing for people.

Due to their unique roles, ED nurses and physicians described varying types of interactions with patients. One nurse (26) described having to deal directly with frustrated patients on behalf of the care team:

I think as the nurse you feel like the middle man, and you’re just kind of making those connections…making sure [physicians and residents] follow through… because I’m the nurse that’s going back into the room and if you don’t have that solved, the patient’s going to get frustrated with you.

Notably, a number of physicians were very thoughtful about the distinct roles and burdens that nurses face. One physician (23) summarised this sentiment:

My guess would be [nurses]…probably get the most frustration. Cause they gotta sit and deal with this patient the whole time. I can see them [patients] and I move on…And I would imagine it’s a huge source of frustration for [nurses]. Because the patients- some of them, they’re constantly asking you for things, they want stuff, they’re trying to leave…or some of them are just outright verbally abusive.

Both nurses and physicians repeatedly identified three types of patients as the most challenging: frequent users of the ED, substance use patients, and psychiatric patients. Many providers admitted to having negative pre-existing attitudes toward these populations, who were considered to be exceptionally time and energy consuming. One nurse (42) commented,

It is a constant source of frustration for me when… the psych patient who doesn’t necessarily, usually does not have a medical complaint, gets the most attention because they’re the loudest, squeakiest wheel.

Hospital factors

Many ED providers experienced negative emotions in response to insufficient hospital resources. Nurses specifically identified understaffing, particularly at night-time, as a source of stress and frustration across academic and community settings. Several nurses felt that ‘chronic understaffing’ and ‘chronic overworking’ made it difficult to maintain staff. As one nurse (37) commented,

I think that’s the constant problem…[we] continually outgrow our space and we continually understaff, which puts a lot of stress on the department and on the staff, which contributes to our high turnover rate.

Consulting physicians were another significant source of frustration. Physicians discussed negative experiences with uncooperative or unhelpful consultants. One physician (22) described how this can harm the patient–provider relationship, resulting in additional stress for physicians:

Consults that don’t have the same level of urgency as you do…and you’re trying to advocate for the patient, the patient gets mad at you that you’re not taking care of them, the consults mad at you because they think that you’re bothering them unnecessarily, and so you’re stuck in the middle and it feels like no one is on your side, which is also very frustrating.

ED personnel, on the other hand, were often perceived in many hospitals as part of the same community and were frequently discussed in positive terms. As unique as nurses’ and physicians’ experiences are, there was a remarkable overlap in the respect and appreciation they expressed for their ED colleagues. As one nurse (77) stated,

We count on each other, we deal with those situations - sad, happy, angry - all together.

Providers varied in their assessments of teamwork within their EDs, with some reporting strong, close-knit team environments and others discussing challenges with physician to nurse communication. While a number of providers voiced frustrations with a perceived lack of teamwork, the majority mentioned positive emotions and a sense of support in discussing their ED colleagues.

System-level factors

Overcrowding in EDs dominated discussion across providers and hospitals. Providers repeatedly remarked on the stress they experience working within inadequate spaces to serve a high volume of patients. They spoke about delivering large amounts of patient care in hallways, which brought up concerns about patient privacy, as well as quality of care and safety. One physician (23) described the effect of overcrowding on his mood:

Most days, I’m excited…other days that immediately disappears as soon as I walk in and see the board and see that there’s 20 plus people in the waiting room and we have no beds available. Then, I usually switch quickly to despair.

Providers identified boarding—when patients who are admitted or awaiting transfer to another hospital or care facility remain in the ED until inpatient beds become available—as a major factor contributing to space issues. One physician (29) described a taxing boarding process:

They’re not emergency department patients anymore, but we are responsible for them, and that just increases our census…it increases our task shifting, and it changes our cognitive burden…you don’t have the inpatient teams or all those other sorts of things that are supposed to be backing you up.

Providers identified other system-level causes of overcrowded EDs, including a shortage of primary care providers. One physician (39) described how difficulty getting a primary care appointment can steer patients to the ED:

…primary care physicians will keep a certain number of sick visits and those sick visits, they fill up over the course of the morning and early afternoon and after that everything is, ‘Well why don’t you go to the ED?’

Feelings of frustration and despair were exacerbated by limited resources, sentiments that were magnified within community hospitals where resources such as MRI, ultrasound, and sufficient beds were often unavailable. Although these concerns were sometimes expressed about a specific hospital, participants often framed these concerns as a broader societal issue. One nurse (40) remarked:

Medicine and society meet in the ER [emergency room]– well we are not doing a very good job then [of] meeting the needs of society.

Another physician (63) voiced a common concern about the business side of medicine and other systems that ED providers interact with:

The system was designed by administrators, by finance people, people who are not engaged in healthcare…the federal government has its input on our system… the insurers have their input on it. Everybody’s motivations and finances don’t align.

There was large agreement that EDs are not equipped to adequately serve homeless persons, patients with primary psychiatric conditions, and substance use populations. These populations often require boarding and observation, which exacerbate overcrowding and issues around resource use. Reflecting on this, providers expressed disappointment, anger, and frustration with the nationwide shortage of detox programmes, psychiatric facilities, and homeless shelters. As one nurse (24) said,

The frustrations that I think I have, and I think the staff often have…are the infrastructures [are] not out in the community necessarily to support a lot of these patients.

Impacts of provider emotions on patient care and safety

The majority of ED providers recognised the potential for their emotions to impact their clinical decision making. As one physician (68) noted, this can happen when providers are not aware of it:

Emotions subconsciously play a role in every single patient and how you work them up, and how you diagnose them, and what you do for them.

Providers discussed how negative and positive emotions elicited by a patient might impact that patient’s care, as well as how emotions elicited in one situation can influence clinical decision making in subsequent cases.

Some providers noted that if a patient had elicited negative emotions, providers would go into that patient’s room less often, which was considered a natural inclination for anyone to have. Providers noted various ways in which this decrease in face time might contribute to diagnostic error. One physician (10) described how leaving an interaction with an angry patient too quickly might contribute to error:

When I see a relationship with a patient has no longer value added…I will leave that interaction and it is certainly possible that in doing that I’m leaving some data in that room that I should have …I do think it is likely that when you have significantly contentious relationships with patients that … you don’t gain as much data [and to an] extent that could lead to diagnostic error.

A few providers also spoke of ordering tests that allow for quicker discharge in an attempt to minimise face time with patients who elicited negative emotions. As one physician (57) explained,

Someone who’s treating you poorly, you could order less tests than you probably should. Maybe you’re like, ‘If I order a CAT scan, they’ll be here 3 more hours; if I order an X-ray, they’ll be here 40 min.’ And honestly the CAT scan’s a much more detailed picture, gives you more information.

Providers also described how their positive emotions can enhance patient care. When patients elicited positive emotions via kindness, appreciation, or simply by not being unpleasant, some providers described going above and beyond. One nurse (46) noted:

We all know there’s patients that … you have just such good emotions about and you will go that extra mile, you will take that time, you will make sure that their labs are done, and as soon as those labs come out, you’re looking for them and you’re going to go in and talk to them about it…

Some providers also experienced emotional carryover, such that emotions triggered by one patient or situation influences the next patient’s care. As one physician (47) said,

There is no question that that affects how you deal with the next case. You’re not in the same emotional state as you were before.

Although participants reported making efforts to ‘give everyone the benefit of the doubt and start off new’ (71) with every patient encounter, they also acknowledged how their pre-existing emotions could directly and indirectly shape patient care.

Providers’ strategies to manage emotional challenges

Recognising the potential influence of their emotions on clinical decision making, most providers described implementing strategies to manage their emotions, which are summarised in box 1. Providers described practising emotional disengagement/detachment, suppression, and compartmentalisation. Many also pointed out that the constant succession of patients provided a ‘welcome distraction’ from emotional difficulty, stating that the fast pace of the ED leaves little to no time to process emotions. Though some expressed discomfort in developing emotional distance, providers recognised its adaptive value. One nurse (24) pointed out:

Box 1. Strategies to manage emotions (representative quotes).

A. Disengagement/detachment, suppression, compartmentalisation

I mean I think the longer you do it, the more numb you get a little bit. So I think that probably contributes to my even keel attitude. It’s just sort of like meh, okay, this happened, and we’ll deal with it whatever it might be, whereas you might get a little more worked up earlier on in your career. So it’s sort of burn out, but at the same time it’s also adaptive. (Physician 52)

Within emergency medicine… you like compartmentalise, you see that patient and…it doesn’t matter what happens in that room, you leave it in the room and you go on to see the next patient. And there’s…an element of, of toughness that you don’t, you don’t let it affect your work. (Nurse 42)

I think that [the] only way that people last in emergency medicine is they just-- not that they stop caring-- but they stop engaging that emotion. I think it’s still there, but I think they just, they don’t allow it to surface. (Nurse 24)

B. Distraction

I think, to a certain extent, the - just the volume and acuity just forces you to do it in a sense, like you know that the -you’ve had a bad situation - something that has stressed you out or been emotionally difficult - but you have - you can see 10 tasks in front of you that sort of distract you from that you know, and you have to follow-up on that x-ray or go see the next person with belly pain. They’re not going anywhere and you have to do it, so maybe just the work itself just kind of distracts you from it. (Physician 72)

You sort of put blinders on and you just do what you need to do to get through it. There’s not a lot of time to think about it … you’re reacting. You’re putting out fires, you’re seeing this patient and then moving on. (Nurse 42)

C. Cognitive reappraisal

I think again, like with my experiences, I just try and look at the big picture - I’m like okay take a deep breath like, I’m fine, I’m not sick, they’re sick, you know maybe there’s more issues going on with their family and them as a patient, but I can’t let it bother me because there’s people in here that are dying and I’m not the one that’s dying, so I can sit here and complain and be grumpy and give them attitude, but what’s, where’s that going to get me? (Nurse 48)

You can either be incredibly frustrated … and say that, “Oh we’re kind of left to pick up the pieces from a broken system.” And see the people who are coming in with kind of minor illnesses and complaints and say, you know, “You should’ve gone to your PCP [primary care physician] for this, or Urgent Care, and kind of resent those patients for coming to the emergency department. I take a very different approach, personally, to that, just because I think those patients are always gonna come to the emergency department as long as our system is the way it is now. And if you kind of feel defeated by those patients … it’s gonna create negative energy that’s gonna eat at you, ultimately… So I tend to look at it from a more positive perspective, which is that our system is very difficult to navigate. And being kind of a resource for the most vulnerable patients in our society, it is, again, a privilege, and is an opportunity to make a difference in someone’s life. (Physician 14)

D. Increased vigilance

I think when we have patients who push our buttons, I think one of the things that we learn is how to recognize who those patients are, and know that in those scenarios, you have to err on the side of doing more because your instinct is to not do that. And when they’re like really getting to you, and just being aware that you’re not thinking clearly, and sort of recognizing when you’re feeling that emotion, and err on the side of being more conservative than your sort of gut is telling you to be because you’re having an emotional response there. (Physician 54)

I try to just explicitly remind myself to think again and make sure that I’m not just snapping to judgements or kind of closing the encounter early because it’s annoying. Potentially, I’ll do a little bit more testing if I’m feeling like that kind of internal urge of just I think I’m blowing this person off. If I’m being honest, there’s probably in some cases just the sense of let’s just get this patient admitted and let it kind of figure itself out over time. We obviously try to limit that, but I’m sure it plays in it sometimes. (Physician 13)

E. Other strategies: taking breaks, seeking social support, humor, self-care

Like from … going from a really sad situation, I typically pause consciously and take a deep breath. I may go to a restroom, wash my face. (Physician 65)

…just being around people that can sympathise with you, like your colleagues…every case is potentially really emotional and hard … nobody knows that like your [colleagues]. (Nurse 24)

Despite all this, the stress, like we often turn it around and make it something that’s like humorous…and it’s not meant to be disrespectful to patients in any way but it’s just, it’s how you cope with these situations. (Physician 7)

I mean, there, there are times where I bury it you know. There are times where I definitely don’t feel like I can do that and need to talk about it… [I like] exercise and being outside, like going to yoga, going hiking. I like to ski. (Nurse 27)

I think if we wore all of those emotions on our sleeve for every day we worked…you’d last about two months.

Another nurse (30) commented on the delicate balance between debilitating sensitivity and total detachment:

…you kind of have to turn off some sort of emotion so that you can do what you need to do for your patients. [You can’t be] crying at every cancer case or every sick kid or whatever…of course you should always feel something. If you don’t feel anything, you should leave. But…it’s a fine balance between doing your job and not letting it really take over vs you know, just not feeling anything.

Although providers most often reported emotional detachment, suppression, and distraction, they noted that these strategies were not always possible. In these moments, providers described reappraising the situation at hand, seeking support from colleagues or loved ones, taking momentary breaks, and stepping away from difficult situations.

Many providers also described making efforts to overcome negative emotional influences on patient safety. A few providers reported being extra vigilant when treating patients who elicited negative emotions. Through awareness of their biases, these providers felt they were able to prevent unfair treatment of these high-risk patients. One physician (64) noted:

When you don’t like a patient, it’s kind of a setup for missing something and so what I usually try to do is…do a real, you know, a really thorough exam. So I try to overcompensate by finding objective data about that person that would kinda lead me to the right diagnosis.

Providers also discussed obtaining support from one another as a way of coping, as shared experiences in the ED were thought to create a strong bond among colleagues. A shared sense of humour was identified as another positive coping mechanism. Finally, a few providers discussed the importance of engaging in activities outside of work that contribute to well-being, such as exercising and spending time with family. As one nurse (25) said,

I feel like if you take care of yourself first, then you can take care of other people so much easier. If you’re not like mentally and physically well yourself, then it makes it so much more difficult.

Discussion

Our results provide a rare view into the emotional lives of ED physicians and nurses. Providers reported experiencing a wide range of emotions (reflected in leading models of emotion28–31) in response to patient, hospital, and system-level factors. Notably, providers highlighted system-level factors as significant sources of negative emotion. Many described adverse effects of understaffing and overcrowding on their moods, a finding that aligns with recent work showing a relationship between overcrowding and negative sentiment among ED providers.32

While providers voiced frustrations with certain types of ED visits, which some have described as inappropriate,33, 34 providers were also aware of reasons underlying some of these visits. Socioeconomic vulnerabilities, barriers to outpatient care, and limited community-based services lead many to the ED for services that the ED is ill-equipped to provide (eg, psychiatric or substance use services) or not designed to provide (eg, food or shelter), or for services that are arguably unnecessary and expensive for the ED to provide (eg, treatment for seasonal colds).33, 34

System-level issues are challenging to address without significant community-based interventions,35 broad healthcare reform, and changes to public policies.36 Despite these challenges, efforts to raise awareness of the myriad societal factors driving people to use the ED may prove helpful in reducing negative emotions and biased judgements of these patients.37 Considerable research demonstrates that individuals tend to automatically attribute the causes of other people’s behaviours to internal characteristics (eg, seeking ED care due to laziness or convenience) without considering the influence of broader contextual factors (eg, lack of insurance or unemployment).38 This tendency, referred to as the ‘fundamental attribution error’, is not inevitable; correction processes can increase consideration of situational factors.39, 40 Thus, provider awareness of broader, societal issues driving patients to the ED is particularly important at the point of care when providers are directly engaged with patients.

Regardless of the source of their emotions, the majority of providers expressed awareness that negative (but not positive) emotions can adversely influence clinical decision making and patient care. In an effort to reduce risks to patients, providers reported widespread efforts to remain emotionally detached. They also reported using a variety of other emotion regulation strategies, all of which have been extensively investigated in the psychology literature.41–51

Research demonstrates that emotion disengagement strategies (eg, distraction and suppression) tend to be least effective, whereas emotion engagement strategies (eg, cognitive reappraisal) are most effective.43, 51 Nonetheless, our findings suggest that emotional disengagement may be effective in allowing providers to perform in the ED; however, if distracting oneself from patients who elicit negative emotions is associated with avoidance, this can be detrimental to patients. Further, actively suppressing emotions can lead to emotional rebound in which suppressed emotions may resurface52, 53 and influence interactions with other patients or staff. Suppression can also adversely affect cognitive functioning.54, 55

Whether providers effectively employ emotion regulation strategies in the ED is a topic of significant importance for future research. Importantly, our results demonstrate that many providers believe their strategies are effective and help guard against adverse influences of negative emotions on patients. However, the extent to which these strategies actually mitigate patient safety risks remains unclear. In addition, although providers believe that positive emotional responses to patients improve care, such emotions also have the potential to increase risk by prompting overtesting and overtreatment.37 Thus, future work on the effectiveness of emotion regulation strategies among healthcare providers should consider both negative and positive emotions.

Emotion regulation is a key component of emotional intelligence,56 which refers to the ability to be aware of and to understand emotional states in oneself and others, and to regulate one’s emotions effectively.55, 56 Research demonstrates that emotional intelligence is positively associated with medical students’ performance in courses on communication and interpersonal sensitivity (ie, ‘bedside manners’),57 residents’ performance in a simulated emergency,58 and nurses’ physical and emotional caring for patients.59 Further, research suggests an indirect and negative relationship between physicians’ emotional intelligence and malpractice risk.60 Thus, emotional intelligence is a critical skill that should be actively cultivated among healthcare professionals and students through formal emotion management, regulation, and skills training.17, 58–64 Considerable evidence65, 66 demonstrates that such training interventions increase emotional intelligence in diverse samples, including students, managers, teachers, and police officers.

In addition to formal training, students and trainees learn powerful and lasting lessons informally from mentors and other role models who transmit cultural values and norms inherent in the practice of medicine. Such norms generally support emotional suppression and discourage discussion of emotions.64, 67–70 Indeed, one study demonstrated that students’ emotional intelligence declined by the end of their second year of medical school.61 Increased awareness and interventions are needed to shift cultural norms to support meaningful, honest, and safe discussions about providers’ emotional experiences and effects on patient safety.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has strengths and limitations. Our sample is large for a qualitative study. We recruited physicians and nurses with different leadership positions and experience levels from multiple academic and community hospitals. This increases the transferability of our findings and generates confidence in the reliability of the themes that emerged. While we excluded resident physicians and other trainees to target experienced providers who are likely very familiar with hospital and system-level factors in emergency medicine, it will be important to extend this work to include residents, trainees, and advanced practice providers who increasingly care for patients in EDs. Finally, the transferability of our findings may be limited to hospitals in the Northeastern USA.

conclusion

A comprehensive research agenda to understand the role of emotions in patient safety is long overdue. The current study represents the first attempt to establish a data-driven model of emotion-eliciting factors in the ED, effects of provider emotions on patient safety, and emotion regulation strategies that providers employ. The results highlight a wide array of opportunities for researchers, educators, and clinicians to develop, evaluate, and implement interventions to mitigate risks that arise from provider emotions. Although research investigating emotions in patient safety is still in its early stages, work on emotions has a long, rich, and well-established history in psychology. Moving forward, we strongly encourage interdisciplinary research and collaborations that capitalise on the unique theoretical and methodological strengths that different disciplines can bring to the study of this complex topic. Such work will generate new insights, approaches, and solutions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Pat Croskerry and Mark L Graber for their valuable feedback and contributions to the manuscript during the review process.

Funding

This project was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (grant number R01HS025752), US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) awarded to LMI. The authors are solely responsible for this document’s contents, findings and conclusions, which do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Readers should not interpret any statement in this report as an official position of AHRQ or of HHS.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval The institutional review board at the University of Massachusetts Amherst approved this study (protocol number 2016–3160).

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement No data are available. The data generated in this study are confidential interview transcripts that are not available for sharing.

references

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2016 emergency department summary tables. Atlanta, GA: U.S: department of health and human services, 2016. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/emergency-department.htm [Accessed 1 Aug 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Croskerry P Ed cognition: any decision by anyone at any time. CJEM 2014;16:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croskerry P, Sinclair D. Emergency medicine: a practice prone to error? CJEM 2001;3:271–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act (EMTALA), 1986. Available: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EMTALA/index.html [Accessed 1 Aug 2019].

- 5.Croskerry P, Norman G. Overconfidence in clinical decision making. Am J Med 2008;121:S24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berner ES, Graber ML. Overconfidence as a cause of diagnostic error in medicine. Am J Med 2008;121:S2–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croskerry P The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med 2003;78:775–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huntsinger JR, Isbell LM, Clore GL. The affective control of thought: malleable, not fixed. Psychol Rev 2014;121:600–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isbell LM, Lair EC. Moods, emotions, and evaluations as information. Oxf Handb Soc Cogn 2013:435–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lerner JS, Li Y, Valdesolo P, et al. Emotion and decision making. Annu Rev Psychol 2015;66:799–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyer RS, Clore GL, Isbell LM. Affect and information processing In: Zanna MP, ed. Advances in experimental social psychology. San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press, 1999: 1–77. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heyhoe J, Birks Y, Harrison R, et al. The role of emotion in patient safety: are we brave enough to scratch beneath the surface? J R Soc Med 2016;109:52–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kozlowski D, Hutchinson M, Hurley J, et al. The role of emotion in clinical decision making: an integrative literature review. BMC Med Educ 2017;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Djulbegovic B, Elqayam S. Many faces of rationality: implications of the great rationality debate for clinical decision-making. J Eval Clin Pract 2017;23:915–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croskerry P Clinical Decision Making. In: Barach PR, Jacobs JP, Lipshultz SE, eds. Pediatric and congenital cardiac care: volume 2: quality improvement and patient safety. London: Springer London, 2015: 397–409. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croskerry P, Abbass AA, Wu AW How doctors feel: affective issues in patients’ safety. The Lancet 2008;372:1205–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Croskerry P, Abbass A, Wu AW. Emotional influences in patient safety. J Patient Saf 2010;6:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med 1978;298:883–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounters in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1069–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahn SR, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, et al. The difficult patient: prevalence, psychopathology, and functional impairment. J Gen Intern Med 1996;11:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerrard TJ, Riddell JD. Difficult patients: black holes and secrets. BMJ 1988;297:530–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hox JJ, Boeije HR, Collection D. Primary vs. Secondary In: Kempf-Leonard K, ed. Encyclopedia of social measurement. New York: Elsevier, 2005: 593–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: second edition: techniques and procedures for developing Grounded theory. 2nd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birks M, Mills J. Grounded theory: a practical guide. 2nd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaz B 2017–2018 compensation report for emergency physicians shows steady salaries. ACEP now, 2017. Available: https://www.acepnow.com/article/2017-2018-compensation-report-emergency-physicians-shows-steady-salaries/ [Accessed 22 Oct 2019].

- 26.Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 3rd edn Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc Probl 1965;12:436–45. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyle GJ, Saklofske DH, Matthews G. Measures of personality and social psychological constructs. 1st ed Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier Science & Technology, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell JA. A circumplex model of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol 1980;39:1161–78. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:1063–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clore GL RS WJ, Dienes B, et al. Affective feelings as feedback: Some cognitive consequences In: Theories of mood and cognition: A user’s guidebook. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2001: 27–62. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agarwal AK, Hahn L, Pelullo A, et al. Capturing real-time emergency department sentiment: a feasibility study using Touch-Button terminals. Ann Emerg Med 2019;0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McHale P, Wood S, Hughes K, et al. Who uses emergency departments inappropriately and when - a national cross-sectional study using a monitoring data system. BMC Med 2013;11:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naouri D, Ranchon G, Vuagnat A, et al. Factors associated with inappropriate use of emergency departments: findings from a cross-sectional national study in France. BMJ Qual Saf 2019:bmjqs-2019-009396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Norton L, et al. Effect of community health worker support on clinical outcomes of low-income patients across primary care facilities. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1635–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaiyachati K, Kangovi S. Inappropriate ED visits: patient responsibility or an Attribution bias? BMJ Qual Saf 2019:bmjqs-2019-009729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Isbell LM, Tager J, Beals K, et al. Emotionally-Evocative Patients in the Emergency Department: A Mixed-Methods Investigation of Providers’ Emotional Responses and Implications for Patient Safety. BMJ Qual Saf 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross L The Intuitive Psychologist And His Shortcomings: Distortions in the Attribution Process In: Berkowitz L, ed. Advances in experimental social psychology. Academic Press, 1977: 173–220. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trope Y Identification and inferential processes in dispositional Attribution. Psychol Rev 1986;93:239–57. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilbert DT, Pelham BW, Krull DS. On cognitive busyness: when person perceivers meet persons perceived. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:733–40. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Rev Gen Psychol 1998;2:271–99. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations. In: Handbook of emotion regulation. 2nd edn New York, NY, US: Guilford Press, 2014: 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: current status and future prospects. Psychol Inq 2015;26:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheppes G, Scheibe S, Suri G, et al. Emotion regulation choice: a conceptual framework and supporting evidence. J Exp Psychol 2014;143:163–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaillant GE. Adaptive mental mechanisms: their role in a positive psychology. Am Psychol 2000;55:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campbell L, Martin RODA, Ward JR An observational study of humor use while resolving conflict in dating couples. Pers Relatsh 2008;15:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lefcourt HM, Davidson K, Shepherd R, et al. Perspective-Taking humor: accounting for stress moderation. J Soc Clin Psychol 1995;14:373–91. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samson AC, Gross JJ. Humour as emotion regulation: the differential consequences of negative versus positive humour. Cogn Emot 2012;26:375–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samson AC, Gross JJ. The dark and light sides of humor: An emotion-regulation perspective In: Positive emotion: integrating the light sides and dark sides. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014: 169–82. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fredrickson BL. What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology 1998;2:300–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gross JJ. Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998;74:224–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sayers WM, Sayette MA. Suppression on your own terms: internally generated displays of craving suppression predict rebound effects. Psychol Sci 2013;24:1740–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wegner DM, Gold DB. Fanning old flames: emotional and cognitive effects of suppressing thoughts of a past relationship. J Pers Soc Psychol 1995;68:782–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Richards JM, Gross JJ. Personality and emotional memory: how regulating emotion impairs memory for emotional events. J Res Pers 2006;40:631–51. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 2003;85:348–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional intelligence. Imagin Cogn Pers 1990;9:185–211. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Libbrecht N, Lievens F, Carette B, et al. Emotional intelligence predicts success in medical school. Emotion 2014;14:64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bourgeon L, Bensalah M, Vacher A, et al. Role of emotional competence in residents’ simulated emergency care performance: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:364–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nightingale S, Spiby H, Sheen K, et al. The impact of emotional intelligence in health care professionals on caring behaviour towards patients in clinical and long-term care settings: findings from an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud 2018;80:106–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shouhed D, Beni C, Manguso N, et al. Association of emotional intelligence with malpractice claims. JAMA Surg 2019;154:250–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mintle LS, Greer CF, Russo LE. Longitudinal assessment of medical student emotional intelligence over preclinical training. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2019;119:236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luff D, Martin EB, Mills K, et al. Clinicians’ strategies for managing their emotions during difficult healthcare conversations. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:1461–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lundin RM, Bashir K, Bullock A, et al. “I’d been like freaking out the whole night”: exploring emotion regulation based on junior doctors’ narratives. Adv in Health Sci Educ 2018;23:7–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taylor C, Farver C, Stoller JK. Perspective: can emotional intelligence training serve as an alternative approach to teaching professionalism to residents? Acad Med 2011;86:1551–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hodzic S, Scharfen J, Ripoll P, et al. How efficient are emotional intelligence Trainings: a meta-analysis. Emot Rev 2018;10:138–48. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mattingly V, Kraiger K. Can emotional intelligence be trained? A meta-analytical investigation. Hum Resour Manag Rev 2019;29:140–55. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Doulougeri K, Panagopoulou E, Montgomery A. (how) do medical students regulate their emotions? BMC Med Educ 2016;16:312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gaufberg EH, Batalden M, Sands R, et al. The hidden curriculum: what can we learn from third-year medical student narrative reflections? Acad Med 2010;85:1709–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shapiro J Perspective: does medical education promote professional alexithymia? A call for attending to the emotions of patients and self in medical training. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll 2011;86:326–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shapiro J The feeling physician: educating the emotions in medical training. EJPCH 2012;1:310–6. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.