Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To investigate the association of the utilization of Medicare-certified home health agency (CHHA) services with post-acute skilled nursing facility (SNF) discharge outcomes, which included home time, rehospitalization, SNF readmission, and mortality.

DESIGN:

Retrospective cohort study.

SETTING:

New York State fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older admitted to SNFs for post-acute care and discharged to the community in 2014.

PARTICIPANTS:

25,357 older adults.

MEASUREMENTS:

The outcomes included days spent alive in the community (“home time”), rehospitalization, SNF readmission, and mortality within 30- and 90-day post-SNF discharge periods. The primary independent variables were SNF 5-star overall quality rating and receipt of CHHA services within seven days of SNF discharge. Zero-inflated negative binomial regression and logistic regression models characterized the association of CHHA linkage with home time and other outcomes, respectively.

RESULTS:

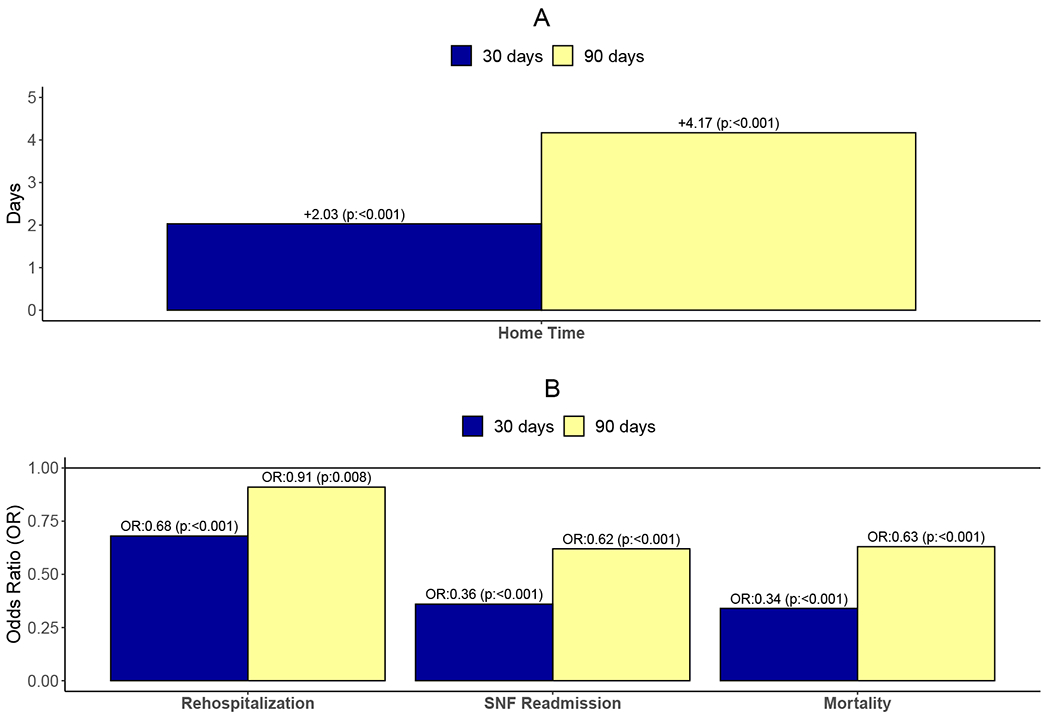

Following SNF discharge, 17,657 (69.6%) patients received CHHA services. In analyses that adjusted for patient-, market- and other SNF-level factors, older adults discharged from higher quality SNFs were more likely to receive CHHA services. In analyses that adjusted for patient- and market-level factors, receipt of post-SNF CHHA services was associated with 2.03 and 4.17 (p<0.001) more days in the community over 30- and 90-day periods. Receiving CHHA services also was associated with decreased odds for rehospitalization (Odds Ratio [OR] =0.68, p<0.001; OR=0.91, p=0.008), SNF readmission (OR=0.36, p<0.001; OR=0.62, p<0.001), and death (OR=0.34, p<0.001; OR=0.63, p<0.001) over 30- and 90-day periods, respectively.

CONCLUSION:

Among older adults discharged from a post-acute SNF stay, those who received CHHA services had better discharge outcomes: they were less likely to experience admissions to institutional care settings and had a lower mortality risk. Future efforts that examine how the type and intensity of CHHA services affect outcomes would build on this work.

Keywords: Care transitions, post-acute care, aging in place, health services utilization

INTRODUCTION

In 2017, about 3.4 million homebound Medicare beneficiaries received home health care provided through Medicare-certified home health agencies (CHHA).1,2 CHHAs provide a wide range of skilled services (e.g., nursing, rehabilitation therapy),1,2 which serve a critical role in helping patients transition to and remain at home. CHHA services are often examined in the context of the hospital-to-home transition for their potential to reduce rehospitalizations.3 Likely due in part to the difficulty in controlling for differences in patients who do and do not receive CHHA services – with few exceptions4 – post-hospitalization home health services typically have been linked with higher hospital readmission rates.3

Older adults also struggle with SNF-to-home transitions.5–7 Most discharged from a post-acute SNF stay receive home health services,5,8 and limited data suggest that home health services may result in improved post-SNF outcomes. For instance, among heart failure patients and a cohort of Midwestern patients, those who received home health care had a reduced hospital readmission risk compared to those who did not receive these services post-SNF discharge.8,9 Nonetheless, although SNF-to-community care transitions are common,10 how CHHA services affect post-SNF discharge outcomes in a general Medicare population is poorly understood.

Post-acute care discharge outcomes traditionally are measured by health events such as emergency department visits, hospital readmissions, and/or mortality. There is increasing interest, however, on patient-centered endpoints, and a highlighted priority of patients and caregivers is days spent at home (“home time”).11 Home time can be calculated from Medicare claims data by examining the number of days alive that were not in a hospital, inpatient rehabilitation facility, or SNF over a specified period.12 To our knowledge, no studies have examined the association between CHHA services and home time following SNF discharge.

Among New York State (NYS) Medicare beneficiaries discharged from a post-acute SNF stay to home, we hypothesized that: 1) consistent with prior studies,7,9 older adults discharged from SNFs with higher quality ratings were more likely to receive CHHA services, and 2) older adults who received CHHA services spent more days in the community compared to those who did not receive these services.

METHODS

Participants and Study Design

Our study population consisted of NYS fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older with an index NYS SNF admission in 2014 following a hospitalization of three or more days. We defined the index SNF admission as being the first SNF admission in 2014 not preceded by an SNF admission in the prior three months. We included beneficiaries who were discharged to the community within 100 days of the SNF admission between January 1, 2014 and October 2, 2014. We followed discharged residents for 90 days post-SNF discharge. We used 2014 data from the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review File,13 Master Beneficiary Summary File,13 Medicare Outpatient Revenue Center File,13 Physician Part B file,13 Home Health Agency claims data,13 Long-Term Care Minimum Data Set 3.0,13 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’(CMS) FY 2014 Final Rule Tables,14 Area Health Resources File,15 the LTCfocus data set,16 and the Nursing Home Compare file managed by CMS.17 The Privacy Board at CMS and University of Rochester’s Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was home time, which we determined by calculating the number of days an older adult was alive and not in an institutional setting such as a hospital (either acute inpatient admission or an observation stay), inpatient rehabilitation setting, or SNF, which is similar to previous studies.12,18 Our secondary outcomes were binary (yes/no) and included rehospitalization, SNF readmission, and mortality. We focused on 30- and 90-day periods post-SNF discharge.

Independent Variable

Our first key independent variable was SNF 5-star overall quality rating, which we treated as a categorical variable with five levels corresponding to each star rating (reference group was 1-star rating). Our second key independent variable was receipt of CHHA services within seven days following SNF discharge (yes/no), which was similar to a prior study.8

Covariates

Our covariates were at the patient-, SNF-, and market-level because many factors can affect the ability of older adults to transition to and remain in the community5,7,19–22 as well as their referral to CHHA services (Supplementary Table S1 shows covariate data sources).9

Patient-level covariates included sociodemographic characteristics, health status and functioning, and other medical information. Sociodemographic characteristics encompassed age, marital status, sex, race, and Medicaid dual eligibility. Health and functional status included number of medical conditions, dementia presence_ENRE, cognitive functioning based on the Brief Interview for Mental Status (0-15; higher scores indicate better cognitive functioning),23 and activities of daily living scores (0-28; higher scores indicate worse functional status).24,25 Other medical information included the number of days hospitalized preceding SNF admission, reason for the pre-SNF hospitalization (medical or surgical ), and number of SNF days.

SNF-level factors included facility ownership (for-profit or non-profit), occupancy, total nursing (registered nurse (RN), licensed practical nurse (LPN), and certified nurse assistant (CNA)) hours per resident day, ratio of RN/total nursing hours per resident day, hospital-based versus freestanding SNF, % Medicare and Medicaid dual eligible patients, and NH-level prevalence of surgical hospitalizations pre-SNF admission.

Market-level variables included metro vs. non-metro county (determined by Rural Urban Commuting Codes) and supply of primary care physicians, hospital beds, SNF beds, and home health agencies per 100,000 people.

Statistical Analyses

We first examined the 30- and 90-day distributions of our primary outcome (home time) and secondary outcomes (rehospitalization, SNF readmission, mortality) and other patient-, SNF-, and market-level factors with receipt of CHHA services. We used chi-square tests and analyses of variance for statistical inference as appropriate. To address our first hypothesis, we conducted multivariable logistic regression analysis with receipt of CHHA services (yes/no) as our outcome with SNF factors as our primary independent variables and other covariates consisting of patient- and market-level factors. To address our second hypothesis, we performed separate multivariable regression models to assess the relationship between receipt of CHHA services and our primary and secondary outcomes in the 30- and 90-day time windows. For home time, we used zero-inflated negative binomial regression models and, for the binary secondary outcomes, we performed multivariable logistic regression analyses. These regression analyses controlled for patient- and market-level factors. We conducted analyses at the beneficiary level using SAS 9.4 and STATA 12.1.

RESULTS

Among our sample, 69.6% received CHHA services within seven days of SNF discharge to the community. Compared to older adults who did not receive CHHA services, those who did were older, were more likely to be female and not married, had more medical comorbidities and functional impairment, spent more days in the hospital and SNF, and were more likely to have been hospitalized for a medical reason (Table 1).

Table 1:

Sample characteristics comparing older adults who did and did not receive Medicare-certified home health agency (CHHA) services within seven days of SNF discharge to the community

| CHHA N: 17,657 | No CHHA N: 7,700 | p-value (χ2 or ANOVA) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | |||

| Average 30-day home time, days | 28.6±4.7 | 26.6±8.3 | <0.001 |

| Average 90-day home time, days | 82.8±17.8 | 78.7±24.5 | <0.001 |

| Hospital stay in 30 days | 12.5% | 16.6% | <0.001 |

| Hospital stay in 90 days | 25.1% | 26.0% | 0.165 |

| SNF stay in 30 days | 4.0% | 9.7% | <0.001 |

| SNF stay in 90 days | 10.5% | 14.7% | <0.001 |

| Died within 30 days | 1.6% | 4.2% | <0.001 |

| Died within 90 days | 5.3% | 7.8% | <0.001 |

| SNF Factors | |||

| For profit | 47.3% | 49.4% | 0.002 |

| Hospital-based | 11.7% | 11.8% | 0.835 |

| Occupancy | 0.9±0.3 | 0.9±0.2 | 0.361 |

| % Medicare residents | 25.1±20.3 | 23.1±18.7 | <0.001 |

| % Medicaid residents | 51.5±23.5 | 53.1±22.7 | <0.001 |

| % surgical DRG | 42.0±14.0 | 43.3±16.1 | <0.001 |

| 5-star overall rating: | <0.001 | ||

| 1 star | 5.1% | 9.7% | |

| 2 stars | 15.1% | 16.2% | |

| 3 stars | 12.7% | 14.7% | |

| 4 stars | 20.2% | 21.3% | |

| 5 stars | 46.8% | 37.8% | |

| Total nursing (RN, LPN, CNA) hours per resident day | 4.13±0.92 | 4.14±0.92 | 0.527 |

| Ratio of RN/total nursing hours per resident day | 0.21±0.09 | 0.20±0.09 | <0.001 |

| Market-Level Factors | |||

| Metro | 95.0% | 90.7% | <0.001 |

| Primary care physicians rate per 100,000 | 93.8±35.2 | 88.8±34.9 | <0.001 |

| Hospital beds rate per 100,000 | 335.3±144.8 | 336.4±158.6 | 0.591 |

| SNF beds rate per 100,000 | 599.1±139.4 | 624.9±168.9 | <0.001 |

| Home health agencies rate per 100,000 | 0.88±0.51 | 0.97±0.59 | <0.001 |

| Patient Factors | |||

| Age | 82.4±8.3 | 80.0±8.6 | <0.001 |

| Female | 67.8% | 62.2% | <0.001 |

| White | 84.3% | 84.8% | 0.321 |

| Married | 33.6% | 36.9% | <0.001 |

| Medicaid dual eligible | 24.6% | 25.8% | 0.029 |

| Alzheimer’s Disease/dementia | 19.4% | 18.9% | 0.430 |

| Days in SNF | 29.2±19.1 | 24.2±18.0 | <0.001 |

| Days spent in hospital prior to SNF stay | 7.1±6.2 | 6.6±6.0 | <0.001 |

| Number of diagnoses | 6.0±3.7 | 5.8±3.6 | <0.001 |

| Surgical DRG prior to SNF stay | 41.0% | 45.7% | <0.001 |

| Admitting diagnosis: | <0.001 | ||

| Circulatory system diseases | 13.5% | 11.9% | |

| Digestive system diseases | 2.8% | 3.2% | |

| Endocrine, metabolic, immunity disorders | 3.1% | 3.6% | |

| Genitourinary system diseases | 3.1% | 3.3% | |

| Injury and poisoning | 9.8% | 7.3% | |

| Musculoskeletal system diseases | 12.7% | 16.1% | |

| Neoplasms | 1.6% | 1.8% | |

| Nervous system and sense organs | 1.7% | 1.6% | |

| Other | 44.6% | 43.7% | |

| Respiratory system diseases | 5.5% | 5.8% | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue diseases | 1.7% | 1.7% | |

| Brief Interview for Mental Status score | 13.0±3.2 | 13.1±3.3 | 0.049 |

| Functional Status Scale (ADL score) | 15.2±5.4 | 14.2±5.9 | <0.001 |

Table 2 shows facility-level factors associated with post-SNF use of CHHA services (full model results in Supplementary Table S2). Patients discharged from SNFs with higher total nursing hours per resident day were less likely to receive CHHA services within seven days of discharge. Additionally, older adults discharged from a 2–5 star (vs. a 1-star) SNF had 42–68% increased odds of having received CHHA services within seven days of SNF discharge. In multivariable analyses, ownership, occupancy, % Medicare and Medicaid dual eligible patients, and ratio of RN/total nursing hours were not associated with receipt of CHHA services.

Table 2:

Facility-level factors associated with post-SNF use of Medicare-certified home health agency (CHHA) services.

| SNF Factors | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p-value | OR | p-value | |

| For profit (ref=non-profit) | 0.92 | 0.002 | 0.97 | 0.405 |

| Hospital-based (ref=free-standing) | 0.99 | 0.835 | 1.03 | 0.587 |

| Occupancy | 1.05 | 0.364 | 1.12 | 0.092 |

| % Medicare residents | 1.01 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.635 |

| % Medicaid residents | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.489 |

| % surgical DRG | 0.99 | <0.001 | 0.99 | <0.001 |

| 5-star overall rating (ref=1 star): | ||||

| 2 stars | 1.78 | <0.001 | 1.56 | <0.001 |

| 3 stars | 1.65 | <0.001 | 1.42 | <0.001 |

| 4 stars | 1.82 | <0.001 | 1.42 | <0.001 |

| 5 stars | 2.36 | <0.001 | 1.68 | <0.001 |

| Total nursing (RN, LPN, CNA) hours per resident day (10-minute increments) | 1.00 | 0.526 | 0.99 | 0.023 |

| Ratio of RN/total nursing hours per resident day (10-minute increments) | 1.20 | <0.001 | 1.04 | 0.310 |

| Observations | 25,357 | 23,504 | ||

Adjusted regression models accounted for patient-, SNF-, and market-level factors. OR = odds ratio.

Older adults who received CHHA services within seven days of SNF discharge to the community spent an additional 2.03 and 4.17 days at home in the 30 and 90 days following SNF discharge, respectively. Receipt of CHHA services also was associated with decreased odds of rehospitalization, SNF readmission, and mortality in the 30 and 90 day follow-up periods (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 1.

The Association of the Receipt of Medicare-Certified Home Health Agency (CHHA) Services with Discharge Outcomes (Reference Group: No CHHA Services Received). Panel A: Primary Outcome: Home Time. Panel B: Secondary Outcomes: Rehospitalization, SNF Readmission, and Mortality.

DISCUSSION

Nearly 7 in 10 of older adults in this study discharged from a post-acute SNF stay to the community received CHHA services. This finding is similar to the 67.4% home healthcare use in a study examining SNF discharge outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries in the Carolinas.5 Congruent with our first hypothesis and prior studies,7,9 older adults in NYS discharged from higher quality SNFs were more likely to have received CHHA services following SNF discharge than those discharged from low quality rated SNFs. In analyses that accounted for patient- and market-level factors, the association between higher quality SNFs with receipt of CHHA was attenuated compared to the unadjusted analyses, suggesting that patient- or market-level factors may have impacted whether an older adult received CHHA services following a SNF stay. That patient-level factors would have influenced linkage to CHHA services is expected as characteristics such as older age, increased disability, medical comorbidity, and living alone are strong indicators that home health services may be needed.3 Compared to 1-star SNFs, older adults discharged from the 2-5 star SNFs had 42-68% increased odds of having received CHHA services. It is unclear why patients discharged from 1-star SNFs had lower utilization of CHHA services (e.g., were there fewer resources available to complete CHHA referrals in 1-star SNFs?) and why total nursing hours were associated with decreased odds of receiving CHHA services (e.g., perhaps other disciplines such as social workers or rehabilitation therapists are more critical in facilitating linkage to CHHA services?). An improved understanding of why linkage to CHHA services varies by overall SNF quality may help identify intervention targets to assist vulnerable older adults in transitioning home.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association between CHHA services following a post-acute stay in an SNF with home time. In support of our second hypothesis, compared to those who did not receive CHHA services, older adults who received CHHA services spent 2.03 and 4.17 more days in the community and had decreased odds of rehospitalization, SNF readmission, and death over the 30- and 90-day follow-up periods. Although there is little empirical evidence specific to the SNF-to-home transition as most care transition interventions have focused on hospital discharges,26 these findings suggests that CHHA services may play a critical role in the success of the SNF-to-home transition for some older adults. Furthermore, CMS has been attempting to incentivize the quality of care while also reducing healthcare costs,27,28 and improving SNF discharge outcomes is increasingly prioritized.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Our study had several strengths. First, we examined the association of CHHA services with a variety of post-SNF discharge outcomes including a patient-centered outcome, home time. The role of CHHA services following SNF discharge and home time are topics for which relatively little is known. Second, utilizing a large cohort of older adults in NYS enabled us to control for many patient and market-level characteristics that may have affected the association of CHHA services with our outcomes of interest.

Our study also had several limitations. First, claims datasets include information recorded for reimbursement rather than for research purposes, which may have affected data completeness and validity. Second, we did not have information to provide more context to home time such as quality of life assessments. Third, our study only had information for NYS Medicare beneficiaries, and future work should consider a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries. Fourth, although we accounted for many individual and market-level covariates, confounding remains a concern. For instance, we did not have information on caregivers or other in-home services, which may have affected discharge outcomes (e.g., perhaps older adults who received CHHA services also had higher levels of informal support or private pay caregiving?). Another consideration is that we only examined receipt of CHHA services, but did not examine referral to CHHA services, and perhaps some older adults had an acute medical problem prior to receiving CHHA services.

Conclusion

Older adults with post-acute SNF stays who received CHHA services following SNF discharge appeared to have more success with the SNF-to-home transition than those who did not receive these services. Examining how the type and intensity of CHHA services affect outcomes would build on this work. Another important step includes identifying barriers to receiving CHHA services after SNF discharge, as addressing these barriers could help improve discharge outcomes and enhance patient experiences. Improved understanding of these issues would help guide efforts into optimizing SNF-to-home transitions for these vulnerable older adults trying to maintain their independence.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1. Covariates and data sources.

Supplementary Table S2: Odds ratios from multivariable logistic regression model for use of Medicare-certified home health agency (CHHA) services.

Supplementary Table S3. Marginal effects from zero-inflated negative binomial regression models (home time) and odds ratios from multivariable logistic regression models (rehospitalization, SNF readmission, and mortality).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding Sources: AS was supported by the Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program, sponsored by the New York State Department of Health, as well as the National Institute on Aging (grant number K23AG058757). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest Checklist: YL serves as an editor for Springer and a consultant for BCG Inc. and Intermountain Healthcare.

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | AS | JO | JW | TVC | YL | HTG | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

*Authors can be listed by abbreviations of their names

Sponsor’s Role: The funders had no role in our article’s design, data analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Presentation: We plan to present some of this article’s findings at the American Geriatrics Society Annual Scientific Meeting in Long Beach, CA, on May 7-9.

REFERENCES

- 1.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare & Home Health Care. Baltimore, MD: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siclovan DM. The effectiveness of home health care for reducing readmissions: An integrative review. Home Health Care Serv Q 2018;37:187–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiao R, Miller JA, Zafirau WJ, Gorodeski EZ, Young JB. Impact of home health care on health care resource utilization following hospital discharge: A cohort study. Am J Med 2018;131:395–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toles M, Anderson RA, Massing M, et al. Restarting the cycle: Incidence and predictors of first acute care use after nursing home discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simning A, Caprio TV, Seplaki CL, Conwell Y. Rehabilitation providers’ prediction of the likely success of the SNF-to-home transition differs by discipline. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2019;20:492–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornell PY, Grabowski DC, Norton EC, Rahman M. Do report cards predict future quality? The case of skilled nursing facilities. J Health Econ 2019;66:208–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carnahan JL, Slaven JE, Callahan CM, Tu W, Torke AM. Transitions from skilled nursing facility to home: The relationship of early outpatient care to hospital readmission. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:853–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weerahandi H, Bao H, Herrin J, et al. Home health care after skilled nursing facility discharge following heart failure hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirschman KB, Hodgson NA. Evidence-based interventions for transitions in care for individuals living with dementia. Gerontologist 2018;58:S129–s140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groff AC, Colla CH, Lee TH. Days spent at home — A patient-centered goal and outcome. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1610–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greene SJ, O’Brien EC, Mentz RJ, et al. Home-time after discharge among patients hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:2643–2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ResDAC. Research Data Assistance Center. 2020. (online). Available at: https://www.resdac.org/cms-data. Accessed January 26, 2020.

- 14.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. FY 2014 Final Rule Tables. 2014. (online). Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY-2014-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY-2014-IPPS-Final-Rule-CMS-1599-F-Tables.html. Accessed May 13, 2019.

- 15.Health Resources & Services Administration. Area Health Resources Files. 2019. (online). Available at: https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf. Accessed January 20, 2020.

- 16.Brown University Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research. Long-term Care: Facts on Care in the US. 2020. (online). Available at: http://ltcfocus.org/. Accessed January 20, 2020.

- 17.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Nursing Home Compare Data Archive: 2014 Data. 2019. (online). Available at: https://data.medicare.gov/data/archives/nursing-home-compare. Accessed January 20, 2020.

- 18.Joynt Maddox KE, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. How do frail Medicare beneficiaries fare under bundled payments? J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:2245–2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, Kane RL. Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S.: A meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 2007;7:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer JL, Langan JC, Krampe J, et al. A model of risk reduction for older adults vulnerable to nursing home placement. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2014;28:162–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang SY, Shamliyan TA, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Not just specific diseases: Systematic review of the association of geriatric syndromes with hospitalization or nursing home admission. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013;57:16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones CD, Falvey J, Hess E, et al. Predicting hospital readmissions from home healthcare in Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:2505–2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saliba D, Buchanan J, Edelen MO, et al. MDS 3.0: Brief Interview for Mental Status. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1539–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1999;54:M546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kansagara D, Chiovaro J, Kagen D, et al. Transitions of care from hospital to home: A summary of systematic evidence reviews and recommendations for transitional care in the Veterans Health Administration. 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing (SNF VBP) Program. 2019. (online). Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/SNF-VBP/SNF-VBP-Page.html. Accessed January 20, 2020.

- 28.Cen X, Temkin-Greener H, Li Y. Medicare bundled payments for post-acute care: Characteristics and baseline performance of participating skilled nursing facilities. Med Care Res Rev 2018:1077558718766996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1. Covariates and data sources.

Supplementary Table S2: Odds ratios from multivariable logistic regression model for use of Medicare-certified home health agency (CHHA) services.

Supplementary Table S3. Marginal effects from zero-inflated negative binomial regression models (home time) and odds ratios from multivariable logistic regression models (rehospitalization, SNF readmission, and mortality).