Abstract

In neuronal exocytosis, SNARE assembly into a stable four-helix bundle drives membrane fusion. Previous studies have revealed that the SM protein Munc18-1 plays a critical role for precise SNARE assembly with the help of Munc13-1, but the underlying mechanism remains unclear. Here, we used single-molecule FRET assays with a nanodisc membrane reconstitution system to investigate the conformational dynamics of SNARE/Munc18-1 complexes in multiple intermediate steps towards the SNARE complex. We found that single Munc18-1 proteins induce the closed conformation of syntaxin-1 not only in the free syntaxin-1 but also in the t-SNARE (syntaxin-1/SNAP-25) complex. These results implicate that Munc18-1 may act as a gatekeeper for both binary and ternary SNARE complex formation by locking the syntaxin-1 in a cleft of Munc18-1. Furthermore, the kinetic analysis of the opening/closing transition reveals that the closed syntaxin-1 in the syntaxin-1/SNAP-25/Munc18-1 complex is less stable than that in the closed syntaxin-1/Munc18-1 complex, which is manifested by the infrequent closing transition, indicating that the conformational equilibrium of the ternary complex is biased toward the open conformation of syntaxin-1 compared with the binary complex.

Subject terms: Single-molecule biophysics, Membrane structure and assembly, Exocytosis, Membrane proteins

Introduction

Neuronal exocytosis for neurotransmitter release is driven by the assembly of the three soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) proteins, which are syntaxin-1 and SNAP-25 in the presynaptic plasma membrane and synaptobrevin in the synaptic vesicle membrane1,2. The assembly of these proteins generates a stable four-helix bundle between the vesicle and target membranes, thus promoting membrane fusion3,4. Although the membrane fusion can be induced by the SNAREs alone in vitro, a number of auxiliary proteins are required for membrane fusion with high speed and high fidelity in vivo5,6. Among those, the Sec1/Munc18 (SM) family proteins Munc18-1 and Munc13-1 are known to be essential for SNARE-mediated membrane fusion7–9.

Extensive studies on roles of the Munc18-1 and Munc13-1 in the membrane fusion have established that these proteins are critically involved in the regulation of SNARE complex formation. Initially, Munc18-1 induces the closed conformation of syntaxin-1, locking the syntaxin-1 protein in a cleft of Munc18-1, that inhibits the spontaneous binding of SNAP-25 to syntaxin-110,11. Recent reports have revealed that the MUN domain of Munc13-1 promotes the transition from the syntaxin-1/Munc18-1 complex to the ternary SNARE complex in the presence of SNAP-25 and synaptobrevin, suggesting that Munc13-1 plays a role in opening syntaxin-1 for the subsequent SNARE assembly12–15. On the other hand, it is also known that Munc18-1 stimulates membrane fusion when it binds to a fully assembled SNARE complex16–18.

Despite such major advances, many important questions concerning the mechanisms underlying the precise regulation of SNARE complex formation by the Munc18-1 and Munc13-1 still remain unanswered. For instance, the kinetic pathway of SNARE assembly has been extensively studied, but the sequential order of binding of the other SNARE partners (SNAP-25 and synaptobrevin) has not yet been clarified13,19–25. Furthermore, the structural and dynamic features of intermediates remain elusive.

Here, we perform a single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay with a nanodisc membrane reconstitution system26,27, which allows us to observe conformational dynamics of syntaxin-1 in the intermediate stages of SNARE assembly in the presence and absence of Munc18-1. In this unique experiment, we focused on the mechanism underlying the regulation of SNARE assembly by Munc18-1 in the intermediate states. Our results strongly suggest that Munc18-1 acts as a chaperone not only in the syntaxin-1 alone but also in the t-SNARE complex (syntaxin-1/SNAP-25 complex) by dynamically inducing and modulating the closed conformation of syntaxin-1.

Results

Single-molecule FRET assay for observing intermediate states during t-SNARE complex formation

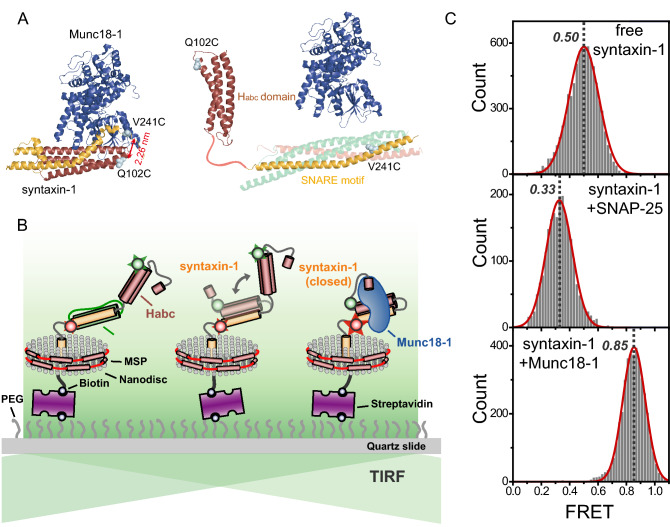

To investigate the conformational dynamics of syntaxin-1 during t-SNARE complex formation, we first labeled syntaxin-1 with a FRET dye pair, the fluorescence donor Cy3 at the Habc domain and the acceptor Cy5 at the SNARE motif of syntaxin-1. We selected the labeling positions Val241 and Gln102 such that substantial FRET changes arise during the transitions between the open and closed conformations of syntaxin-1 as depicted in Fig. 1A. Using the SDS resistance assay, we confirmed that cysteine mutations does not negate the SDS-resistant property of the SNARE complex (Supplementary Fig. S1). For membrane-reconstitution of syntaxin-1, we employed a nano-sized lipid bilayer called a nanodisc and reconsitituted a single syntaxin-1 protein into a nanodisc (see “Methods” section). To observe the conformational changes in syntaxin-1 in real time, we immobilized the nanodisc containing a doubly-labeled syntaxin-1 on a polyethylene glycol (PEG)-coated imaging surface using biotinylated lipids of the nanodiscs via a streptavidin–biotin interaction and monitored fluorescence signals from single syntaxin-1 molecules individually using a total internal reflection microscope (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Single-molecule FRET measurement of syntaxin-1 conformations in t-SNARE complex formation. (A) Structures of the Munc18-1/syntaxin-1 complex (Protein Data Bank code 3C98) and the SNAREs (Protein Data Bank codes 1SFC for SNARE complex and 1BR0 for Habc domain). The two cysteine mutations, Q102C and V241C, introduced for site-specific dye labeling are indicated. The distance between the Cα atoms of these residues in the Munc18-1/syntaxin-1 complex was estimated to be 2.26-nm. (B) Schematic diagram of single-molecule FRET assay with membrane reconstitution of syntaxin-1. (C) FRET histograms for syntaxin-1 proteins (free syntaxin-1 only, top; with bound SNAP-25, middle; with bound Munc18-1, bottom). FRET values for each construct were obtained by fitting the FRET histograms to a single Gaussian function. To obtain the FRET histograms, all data points for each construct were collected from at least more than 50 time trajectories.

As the previous single-molecule multiparameter fluorescence detection (SmMFD) experiment revealed28, free syntaxin-1 is expected to be in a dynamic equilibrium between the closed and open conformations. In our measurement with free syntaxin-1, however, we were not able to detect such fast transitions between two states in a submilllisecond time scale due to the limited time resolution (Fig. 1C, top). When bound to SNAP-25, however, syntaxin-1 exhibited a much lower FRET distribution than free syntaxin-1 (Fig. 1C, middle), indicating that the binding of SNAP-25 to syntaxin-1opens up the syntaxin-1 conformation. On the other hand, in the presence of bound Munc18-1, we obtained a higher FRET distribution (Fig. 1C, bottom) than that of free syntaxin-1, indicating that Munc18-1 arrests the closed conformation of syntaxin-1. Putting together, although the transitions between the closed and open states in free syntaxin-1 were not directly accessible, most likely due to the fast equilibrium, we could infer the dynamic equilibrium between the two states via FRET peak shift. The mean value of the two FRET peaks corresponding to the closed and open conformations, which obtained from FRET histograms for SNAP-25 and Munc18-bound syntaxin-1 proteins respectively, was similar to the observed FRET value for free syntaxin-1. Collectively, based on these observations, we could clearly assign the observed FRET values to intermediate states during t-SNARE complex formation in the presence of Munc18-1.

Dynamic transitions between the closed syntaxin-1/Munc18-1 complex and free syntaxin-1

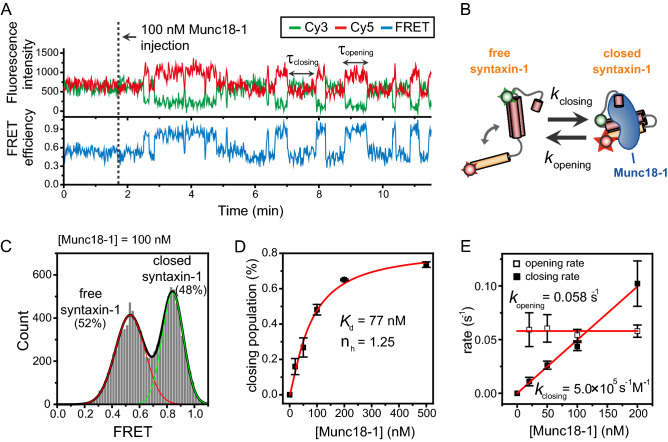

By using the unique capability of our single-molecule FRET assay to identify individual intermediates, we first investigated dynamic interactions between syntaxin-1 and Munc18-1 in real time. Representative time traces of the fluorescence intensity and the FRET efficiency from a real-time Munc18-1 injection experiment is shown in Fig. 2A. In this experiment, Munc18-1 proteins were delivered into the nanodisc-immobilized flow chamber while fluorescence signals from single syntaxin-1 molecules in the nanodisc were being monitored. Before the Munc18-1 injection, fluorescence intensities showed a single-state behavior with middle FRET value (~ 0.50), which indicates the fast dynamic equilibrium between the open and closed states for free syntaxin-1 as described in Fig. 1C. Upon the addition of Munc18-1, however, we observed clear two-state dynamics between a middle FRET state for free syntaxin-1 and a high FRET state (~ 0.85) for the closed syntaxin-1/Munc18-1 complex (Fig. 2A, B). The FRET histogram also established the existence of the two distinct conformational states in the presence of Munc18-1 (Fig. 2C). These observations are in line with the previous crystal structure of the closed syntaxin-1/Munc18-1 complex10.

Figure 2.

Kinetic analysis of the closing and opening of syntaxin-1 by Munc18-1. (A) Representative time traces of fluorescence intensity and FRET efficiency showing the closing and opening of syntaxin-1 by Munc18-1. Cy3 fluorescence, Cy5 fluorescence, and corresponding FRET efficiency are shown in green, red, and blue, respectively. This same color convention is used throughout the paper. τclosing (or dwell time of open syntaxin-1) indicates the time for syntaxin-1 to undergo a conformational change from the open to the closed state, while τopening (or dwell time of closed syntaxin-1) indicates the time for the opposite case. (B) Kinetic scheme for the Munc18-induced syntaxin-1 closing/opening reaction. (C) FRET histograms of syntaxin-1 in the presence of 100 nM Munc18-1. Relative populations for each state were obtained by fitting the FRET histogram to sum of two Gaussian functions. (D) Relative population of the closed syntaxin-1 conformation at varying Munc18-1 concentrations. The dissociation constant and hill coefficient of the Munc18-1 were obtained from a hyperbolic Hill fit of the data. (E) Closing and opening rates at varying Munc18-1 concentrations. The closing rate constant (5.0 × 105 s−1 M−1) was obtained from a linear fit of the data. The average of opening rates is 0.058 s−1. Error bars in (D, E) represent standard deviations obtained from two independent experiments.

To examine the conformational dynamics of syntaxin-1 in connection with Munc18-1in further details, we performed Munc18-1 titration experiments (Supplementary Fig. S2). As shown in Fig. 2D, we determined the dissociation constant and the Hill coefficient on the basis of relative populations of the closed syntaxin-1/Munc18-1 complex as a function of Munc18-1 concentration. Likely due to steric hindrance by the dye labeling of syntaxin-1, the dissociation constant showed a considerable reduction in the binding affinity of Munc18-1 compared to the values obtained by other methods for unlabeled syntaxin-110,29. Nonetheless, the Hill plot analysis revealed a Hill coefficient close to 1, which suggests the 1:1 stoichiometric interaction of Munc18-1 with closed syntaxin-1. This conclusion is further supported by the kinetic analysis of the closing (or binding) and opening (or unbinding) transitions for syntaxin-1 at varying Munc18-1 concentrations (Supplementary Fig. S3). The analysis of the closing and opening kinetics revealed that the closing rate increased linearly with the increase of the Munc18-1 concentration, while the opening rates remained almost constant over the protein concentration range examined (Fig. 2E). Thus, the results suggest that the closed conformation of a single syntaxin-1 is induced by the binding of a single Munc18-1.

Munc18-1 dynamically induces the closed syntaxin-1 conformation even in the t-SNARE complex

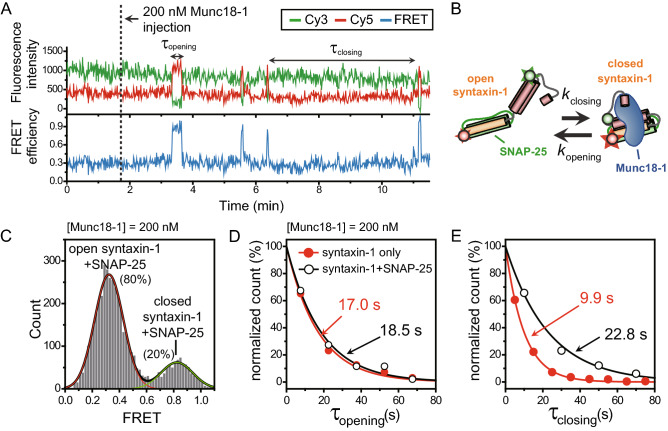

Recent studies strongly suggested that Munc18-1 may act as a regulator for multiple sequential steps during SNARE assembly19–22,24,25,30. However, the dynamic nature of the regulation of the intermediate steps by Munc18-1 is not fully understood. As an initial step toward the understanding of the regulation by Munc18-1, we investigated if Munc18-1 forms a ternary complex with SNAP-25 and syntaxin-1 and induces the closed conformation of syntaxin-1 to possibly prevent the syntaxin-1 from the unregulated binding of the vesicle SNARE (v-SNARE) synaptobrevin. We thus reconstituted syntaxin-1/SNAP-25 complex into a nanodisc and immobilized the nanodisc on the PEG-coated imaging surface for single-molecule FRET measurements. Figure 3A shows the representative time traces of syntaxin-1 in the complex with SNAP-25 from the real-time Munc18-1 injection experiment. Strikingly, upon the addition of Munc18-1, we observed clear two state dynamics between a low FRET state (~ 0.33) that corresponds to the open syntaxin-1 state and a short-lived, but clear high FRET state representing closed syntaxin-1 (Fig. 3A, B). We did not observe any middle FRET state (~ 0.5) reflecting free syntaxin-1, indicating that the observed transitions are not likely due to the dissociation of SNAP-25 from the complex. In this measurement, the existence of transitions from low to high FRET states can be also interpreted as displacement of SNAP-25 from syntaxin-1 by Munc18-1. However, in Fig. 3A, we found that syntaxin-1 exhibited low FRET states, which represent SNAP-25 bound states, whenever Munc18-1 dissociated from the closed complex. By combining this result with the fact that unbound SNAP-25 can rarely recombine with syntaxin-1 because there is a very small amount of SNAP-25 in the detection chamber even if most of SNAP-25 proteins is displaced from syntaxin-1 by Munc18-1, we excluded the possibility regarding the displacement of SNAP-25 by Munc18-1. Therefore, we concluded that Munc18-1 could arrest the closed conformation of syntaxin-1 even in the syntaxin-1/SNAP-25 complex, even if SNAP-25 does not dissociate from the ternary complex. FRET histogram (Fig. 3C) and kinetic analysis (Fig. 3D, E) of these transitions revealed that Munc18-1 showed a significant reduction in the ability to arrest the closed conformation of syntaxin-1 in the presence of bound SNAP-25 compared to that of free syntaxin-1. In addition, it is notable that the frequency of the closing transitions (1/τclosing) in the presence of bound SNAP-25 decreased significantly, while the dwell time of the closed state (τopening) did not show any appreciable changes compared to that of free syntaxin-1. The result indicates that the infrequent closing events are primarily responsible for the decrease of the high FRET population in the presence of bound SNAP-25 (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Direct observation of Munc18-induced the closed syntaxin-1 conformation in t-SNARE complex. (A) Representative time traces of fluorescence intensity and FRET efficiency showing the closing and opening of syntaxin-1 by Munc18-1 in the presence of bound SNAP-25. τclosing (or dwell time of open syntaxin-1) indicates the time for syntaxin-1 to undergo a conformational change from the open to the closed state, while τopening (or dwell time of closed syntaxin-1) indicates the time for the opposite case. (B) Kinetic scheme for the Munc18-induced syntaxin-1 closing/opening reaction in t-SNARE complex. (C) FRET histograms of syntaxin-1 with bound SNAP-25 and 200 nM Munc18-1. Relative populations for each state were obtained by fitting the FRET histogram to sum of two Gaussian functions. (D) Dwell time histograms of closed syntaxin-1 with (open circles) and without (red solid circles) bound SNAP-25. (E) Dwell time histograms of open syntaxin-1 with (open circles) and without (red solid circles) bound SNAP-25. In (C, D), the data were fit to single-exponential decay functions (solid lines) to obtain each average dwell time.

Discussion

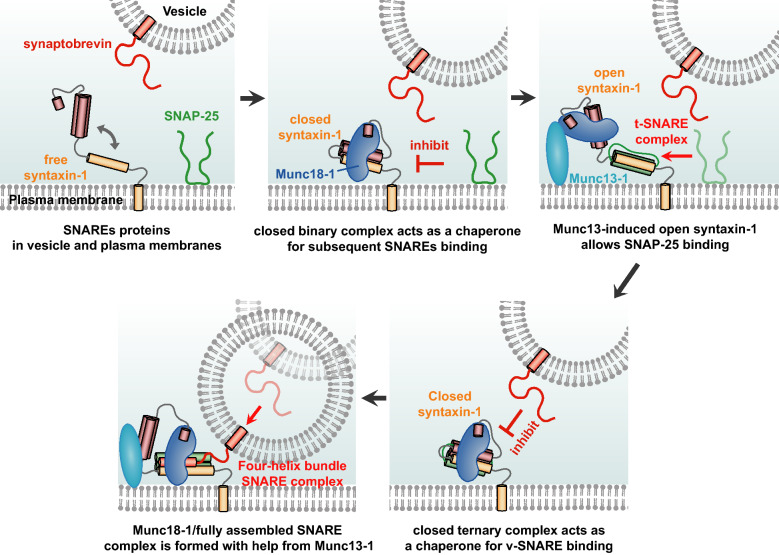

Identification and characterization of key intermediates along the pathway of SNARE assembly has long been a topic of intense interest. Due to the transient nature of these intermediates, however, a deeper understanding of these intermediate states has been hindered by population averaging that is inherent in ensemble measurements. Therefore, we have developed the single-molecule FRET assay with nanodiscs, which was capable of monitoring conformational dynamics of the key intermediates. This method enables the structural and dynamic characterization of the intermediates, which is summarized in Fig. 4 and below.

Figure 4.

Proposed model for the regulation of SNARE assembly by Munc18-1. Based on our observations, we propose a model of sequential Munc18-1 operation during the SNARE assembly process. Munc18-1 first binds to syntaxin-1 with a 1:1 molecular interaction and then induces the closed conformation in syntaxin-1. This closed binary complex acts as a chaperone for the other SNAREs binding by locking the syntaxin-1. When Munc13-1 opens syntaxin-1, SNAP-25 binds to syntaxin-1 and thus the t-SNARE complex is formed with Munc18-1. In this intermediate, the closed ternary complex also acts as a chaperone for the v-SNARE synaptobrevin binding by locking the syntaxin-1 in a cleft of Munc18-1. When the ternary complex is opened by Munc13-1, a fully assembled SNARE complex is formed and then Munc18-1 catalyzes membrane fusion.

Previously, it has long been known that, at the early stage of SNARE assembly, Munc18-1 forms the closed syntaxin-1/Munc18-1 complex and this complex plays a role in the inhibition of the subsequent steps in SNARE assembly10,11,31. Consistently, our results show that Munc18-1 dynamically induces the closed conformation in the syntaxin-1. Our kinetic analysis of the conformational dynamics additionally revealed that the closed syntaxin-1/Munc18-1 complexes are dynamically induced by 1:1 stoichiometric interaction between single syntaxin-1 and Munc18-1 proteins.

This closed syntaxin-1/Munc18-1 complex at the early stage of SNARE assembly has been well characterized previously, but there has been still controversy regarding the subsequent steps. Previous extensive studies have suggested two alternative models for kinetic pathway of subsequent assembly. In the first model, Munc18-1 forms a ternary complex with syntaxin-1 and SNAP-25, which may be a key intermediate for the subsequent binding of synaptobrevin17,21–23. In contrast, the second model suggests that the subsequent intermediate is a template complex in which Munc18-1 arranges initially syntaxin-1 and synaptobrevin in a cleft of Munc18-120,24,25,30. In this study, we found that Munc18-1 could bind to t-SNARE complex and induce the closed conformation of syntaxin-1 similar to the early stage even in this ternary complex, strongly supporting the first model for the kinetic pathway of SNARE assembly. This finding implies that the ternary complex may act as a critical intermediate state for the subsequent synaptobrevin binding and, in this step, Munc18-1 may also play a role as chaperone for subsequent steps by locking the syntaxin-1 in a cleft of Munc18-1.

The existence of the closed syntaxin-1 conformation in the ternary complex raises the question regarding the kinetic difference between two critical intermediates, syntaxin-1/Munc18-1 and syntaxin-1/SNAP-25/Munc18-1 complexes. Our kinetic analysis of the open/closing dynamics of syntaxin-1 in these two intermediates revealed that the closed ternary syntaxin-1/SNAP-25/Munc18-1 complex is less stable than the closed binary syntaxin-1/Munc18-1 complex, which is apparent in the infrequent closing transitions of the ternary complex. Consistent with this observation, a recent electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy study showed that the binding of SNAP-25 to the binary syntaxin-1/Munc18-1 complex biased the conformational equilibrium toward the open conformation of syntaxin-121.

In conclusion, although it remains to be unambiguously proven, our data strongly supports the model that Munc18-1 acts as a functional template and chaperone to promote precise SNARE assembly in multiple intermediates during SNARE assembly with help from Munc13-132.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

Wild-type syntaxin-1A, cysteine mutant of syntaxin-1A, wild-type SNAP-25, wild-type synaptobrevin-2, ApoA1 were expressed and purified based on the previous studies26,33. Plasmid harboring each protein was introduced in E. coli BL21 (DE3) Rosetta pLysS (Novagen). Cells were cultured in Luria–Bertani medium and induced to express protein in early-exponential phase at 16 °C overnight. Cells were harvested and resuspended with PBS. Cells were lysed with sonication. GST fused proteins were purified using glutathione-agarose beads (Thermo Scientific). Proteins were eluted with cleavage of thrombin in thrombin cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 2 mM TCEP, pH 8.0) containing 1% n-octyl glucoside in case of membrane protein.

Munc18 was expressed and purified based on the previous study23. Plasmid harboring the Munc18 was introduced in BL21 (DE3) Rosetta pLysS (Novagen). Cells were cultured in the same manner as mentioned above, protein expression was induced at 20 °C. Cells were harvested and resuspended with lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 20 mM imidazole, 2 mM AEBSF, 2 mM DTT, pH 7.4). Cells were lysed with sonication. The supernatant of lysate was incubated with Ni–NTA bead (Qiagen). Beads were washed with lysis buffer and eluted with elution buffer (25 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 100 mM imidazole, 2 mM AEBSF, 2 mM DTT, pH 7.4).

For dye labeling, syntaxin-1A cysteine mutant was constructed by introducing two mutations (V241C and Q102C), using site-directed mutagenesis. The purified syntaxin-1A mutant should be stored in thrombin cleavage buffer with 1% n-octyl glucoside. Protein, donor dye, and acceptor dye were mixed at a molar ratio of 1:10:20. The mixture of protein and dye was incubated at 4 °C in the dark with gentle shaking overnight. Free dyes were removed by fractionating with PD MiniTrap G-25 desalting column.

Preparation of syntaxin-1 and t-SNARE reconstituted nanodiscs

Reconstitution of the nano-sized lipid bilayer, nanodisc bearing purified recombinant syntaxin-1A (hereafter syntaxin-1) or t-SNARE complex was performed as described previously26. First, phospholipid mixture was prepared by mixing 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (DOPS), and 16:0 Biotinyl Cap PE, 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glcero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N (Biotin-DPPE) (Avanti Polar Lipids) to a molar ratio of 85:15:0.5 at a final concentration of 50 mM. Dried lipid mixtures were resuspended with PBS and stored at − 80 °C deep freezer. Then, phospholipid mixture, sodium cholate, labeled syntaxin-1 (or labeled t-SNARE complex), and ApoA1 protein (membrane scaffold protein) were mixed to a molar ratio 300:5:0.25:1 and incubated on the ice for 10 min. To generate the binary complex of syntaxin-1A and SNAP-25 (t-SNARE complex), purified syntaxin-1A and SNAP-25 with a molar ratio of 1:1 were pre-incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. The same volume of bio-bead solution was added to induce self-assembly of nanodisc by removing sodium cholate. Mixtures were incubated at 4 °C with gentle shaking. The syntaxin-1 (or t-SNARE complex) reconstituted nanodisc was purified using FPLC equipped with Superdex™ 200 GL 10/30 column (Amersham Bioscience).

Single-molecule FRET experiments

To prevent the non-specific adsorption of nanodiscs and proteins to the surface, cleaned quartz microscope slides and coverslips were coated with polyethylene glycol (m-PEG-5000; Laysan Bio Inc.) and biotinylated polyethylene glycol (biotin-PEG-5000; Laysan Bio, Inc.) in a 40:1 ratio34. A sample chamber was constructed between a microscope slide and a coverslip using double-sided adhesive tape. Nanodiscs containing biotinylated lipids were immobilized on the PEG-coated surface via a streptavidin–biotin interaction. Using a home-built prism-type total internal reflection fluorescence microscope, single-molecule fluorescence images were taken in an imaging buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) with 0.4% (w/v) glucose (Sigma, USA), 1% (v/v) Trolox (Sigma, USA), 1 mg/mL glucose oxidase (Sigma, USA), 0.04 mg/mL catalase (Sigma, USA), 100 mM KCl, Munc18-1 with varying concentration) to reduce photobleaching and blinking of dyes35. During the buffer injection experiments, a new buffer containing Munc18-1 proteins was infused into the detection chamber by using a syringe pump (Fusion 200; Chemyx) while single-molecule fluorescence images from doubly labeled syntaxin-1 were being taken. As an excitation source for two-color FRET, a green laser (532 nm, Sapphire; Coherent) was used. Fluorescence signals from Cy3 and Cy5 were collected using a water immersion objective lens (UPlanSApo 60x; Olympus), filtered by a 532 nm long-pass filter (LP03-532RU-25; Semrock), separated through a dichroic mirror (635dcxr; Chroma), and imaged onto an electron multiplying (EM)-charge coupled device (CCD) camera (Ixon DU897D; Andor).

Analysis of single-molecule FRET data

To collect only doubly labeled syntaxin-1 from heterogeneous populations, a few hundred single-molecule spots from the images obtained an acceptor detection channel were selected following 532 nm laser excitation. The time courses of Cy3 and Cy5 signals from a single molecule were extracted from a recorded movie file using IDL (ITT Visual Information Solutions) and analyzed using a custom program written in MATLAB (Mathwork) scripts. To calculate FRET efficiency, which is defined as the ratio of acceptor intensity to the sum of donor and acceptor intensities, data collection including background subtraction and cross-talk correction of the donor signal to the acceptor detection channel was performed. For kinetic analysis of the time traces, FRET states were determined by the standard threshold method using FRET time traces. To obtain the kinetic times, dwell time histograms for each FRET state were fitted by an exponential decay function. Then, the transition rates were determined by inverting the average dwell times. In general, kinetic rates of stochastic transitions in a two-state system can be determined from the average dwell times for two conformational states34.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank all the members of our labs for their kind discussion and help. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the MSIT of Korea Government (2016R1A5A1007318 and 2018R1D1A1B07051186) and by the GIST Research Institute (GRI) grant funded by the GIST.

Author contributions

S.L. and Y.K.S. conceived this project. S.L., Jonghyeok S., Y. J, and H.S. performed and analyzed the experiments with help from Jaeil S., C.J., D.H.K., and Y.K.S. S.L., Jonghyeok S., and Y.K.S. interpreted the data. S.L. and Y.K.S. wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

All data are available upon request to the corresponding authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Sanghwa Lee and Jonghyeok Shin.

Contributor Information

Sanghwa Lee, Email: sanglee@gist.ac.kr.

Yeon-Kyun Shin, Email: colishin@iastate.edu.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-68476-3.

References

- 1.Jahn R, Scheller RH. SNAREs—engines for membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:631–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizo J, Rosenmund C. Synaptic vesicle fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:665–674. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutton RB, Fasshauer D, Jahn R, Brunger AT. Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 A resolution. Nature. 1998;395:347–353. doi: 10.1038/26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poirier MA, et al. The synaptic SNARE complex is a parallel four-stranded helical bundle. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:765–769. doi: 10.1038/1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jahn R, Fasshauer D. Molecular machines governing exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 2012;490:201–207. doi: 10.1038/nature11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizo J, Xu J. The synaptic vesicle release machinery. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2015;44:339–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-060414-034057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toonen RF, Verhage M. Munc18-1 in secretion: lonely Munc joins SNARE team and takes control. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:564–572. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sudhof TC, Rothman JE. Membrane fusion: grappling with SNARE and SM proteins. Science. 2009;323:474–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1161748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizo J, Sudhof TC. The membrane fusion enigma: SNAREs, Sec1/Munc18 proteins, and their accomplices—guilty as charged? Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012;28:279–308. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burkhardt P, Hattendorf DA, Weis WI, Fasshauer D. Munc18a controls SNARE assembly through its interaction with the syntaxin N-peptide. EMBO J. 2008;27:923–933. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Misura KM, Scheller RH, Weis WI. Three-dimensional structure of the neuronal-Sec1-syntaxin 1a complex. Nature. 2000;404:355–362. doi: 10.1038/35006120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma C, Li W, Xu Y, Rizo J. Munc13 mediates the transition from the closed syntaxin-Munc18 complex to the SNARE complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:542–549. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma C, Su L, Seven AB, Xu Y, Rizo J. Reconstitution of the vital functions of Munc18 and Munc13 in neurotransmitter release. Science. 2013;339:421–425. doi: 10.1126/science.1230473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang X, et al. Syntaxin opening by the MUN domain underlies the function of Munc13 in synaptic-vesicle priming. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:547–554. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S, et al. Conformational change of syntaxin linker region induced by Munc13s initiates SNARE complex formation in synaptic exocytosis. EMBO J. 2017;36:816–829. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dulubova I, et al. Munc18-1 binds directly to the neuronal SNARE complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:2697–2702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611318104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen J, Tareste DC, Paumet F, Rothman JE, Melia TJ. Selective activation of cognate SNAREpins by Sec1/Munc18 proteins. Cell. 2007;128:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodkey TL, Liu S, Barry M, McNew JA. Munc18a scaffolds SNARE assembly to promote membrane fusion. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:5422–5434. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e08-05-0538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma L, et al. Munc18-1-regulated stage-wise SNARE assembly underlying synaptic exocytosis. Elife. 2015;4:e09580. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker RW, et al. A direct role for the Sec1/Munc18-family protein Vps33 as a template for SNARE assembly. Science. 2015;349:1111–1114. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dawidowski D, Cafiso DS. Munc18-1 and the syntaxin-1 N terminus regulate open-closed states in a t-SNARE complex. Structure. 2016;24:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jakhanwal S, Lee CT, Urlaub H, Jahn R. An activated Q-SNARE/SM protein complex as a possible intermediate in SNARE assembly. EMBO J. 2017;36:1788–1802. doi: 10.15252/embj.201696270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai Y, et al. Molecular mechanisms of synaptic vesicle priming by Munc13 and Munc18. Neuron. 2017;95:591–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiao J, et al. Munc18-1 catalyzes neuronal SNARE assembly by templating SNARE association. Elife. 2018;7:e41771. doi: 10.7554/eLife.41771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shu T, Jin H, Rothman JE, Zhang Y. Munc13-1 MUN domain and Munc18-1 cooperatively chaperone SNARE assembly through a tetrameric complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:1036–1041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914361117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin J, Lou X, Kweon DH, Shin YK. Multiple conformations of a single SNAREpin between two nanodisc membranes reveal diverse pre-fusion states. Biochem. J. 2014;459:95–102. doi: 10.1042/BJ20131668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lou X, Shin J, Yang Y, Kim J, Shin YK. Synaptotagmin-1 is an antagonist for Munc18-1 in SNARE zippering. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:10535–10543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.631341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Margittai M, et al. Single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer reveals a dynamic equilibrium between closed and open conformations of syntaxin 1. Proc. Natl.. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15516–15521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2331232100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pevsner J, et al. Specificity and regulation of a synaptic vesicle docking complex. Neuron. 1994;13:353–361. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S, et al. Munc18 and Munc13 serve as a functional template to orchestrate neuronal SNARE complex assembly. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:69. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08028-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang B, Steegmaier M, Gonzalez LC, Jr, Scheller RH. nSec1 binds a closed conformation of syntaxin1A. J. Cell Biol. 2000;148:247–252. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker RW, Hughson FM. Chaperoning SNARE assembly and disassembly. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:465–479. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, et al. Dissection of SNARE-driven membrane fusion and neuroexocytosis by wedging small hydrophobic molecules into the SNARE zipper. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:22145–22150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006899108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy R, Hohng S, Ha T. A practical guide to single-molecule FRET. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:507–516. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rasnik I, McKinney SA, Ha T. Nonblinking and long-lasting single-molecule fluorescence imaging. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:891–893. doi: 10.1038/nmeth934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available upon request to the corresponding authors.