Abstract

The purpose of this critical review is to list the sources of aerosol production during orthodontic standard procedure, analyze the constituent components of aerosol and their dependency on modes of grinding, the presence of water and type of bur, and suggest a method to minimize the quantity and detrimental characteristics of the particles comprising the solid matter of aerosol.

Minimization of water-spray syringe utilization for rinsing is suggested on bonding related procedures, while temporal conditions as represented by seasonal epidemics should be considered for the decision of intervention scheme provided as a preprocedural mouth rinse, in an attempt to reduce the load of aerosolized pathogens. In normal conditions, chlorhexidine 0.2%, preferably under elevated temperature state should be prioritized for reducing bacterial counts. In the presence of oxidation vulnerable viruses within the community, substitute strategies might be represented by the use of povidone iodine 0.2%-1%, or hydrogen peroxide 1%. After debonding, extensive material grinding, as well as aligner related attachment clean-up, should involve the use of carbide tungsten burs under water cooling conditions for cutting efficiency enhancement, duration restriction of the procedure, as well as reduction of aerosolized nanoparticles. In this respect, selection strategies of malocclusions eligible for aligner treatment should be reconsidered and future perspectives may entail careful and more restricted utilization of attachment grips. For more limited clean-up procedures, such as grinding of minimal amounts of adhesive remnants, or individualized bracket debonding in the course of treatment, hand-instruments for remnant removal might well represent an effective strategy. Efforts to minimize the use of rotary instrumentation in orthodontic settings might also lead the way for future solutions.

Measures of self-protection for the treatment team should never be neglected. Dressing gowns and facemasks with filter protection layers, appropriate ventilation and fresh air flow within the operating room comprise significant links to the overall picture of practice management. Risk management considerations should be constant, but also updated as new material applications come into play, while being grounded on the best available evidence.

Highlights

-

•

Minimize the use of water-spray syringe during bonding related procedures.

-

•

Consider prerinsing with mouthwash to reduce load of aerosolized pathogens.

-

•

Use a carbide tungsten bur under water cooling conditions after debonding.

-

•

Reconsider whether aligner treatment can be used.

-

•

Risk management considerations should be constant and regularly updated.

The pandemic outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has had a large impact on the frontline of health care workers, and among those, on dentists and orthodontists.1 Besides the public health and economic burdens of the coronavirus disease 2019, it is now evident that its massive spread around the world has imposed great occupational challenges, with the implementation of routine dental services being at stake.2 The nature of the virus’ infectious route, with direct implication of airborne droplets in the form of aerosol, has revealed certain potential hazards underlying conventional and standard oral health care procedures.3 Orthodontic practices are not to be left aside. An aerosol is defined as a suspension system of solid or liquid particles in a gas.4 The term was introduced by Frederick G. Donnan to describe an aero-solution—clouds of microscopic particles in air. The various types of aerosol, classified according to physical form and how they were generated, include dust, fume, mist, smoke, and fog. Aerosol should be differentiated from solid particles staying airborne for some time in the air and the splatter of relatively large sized droplets of water generated by splashes in a dental setting, such as those produced by using the water syringe.

Aerosol-producing dental procedures, along with upcoming concerns, are not new to the dental discipline and at most, these concerns should not be selectively twisted, hampered, or emphasized under the light of the present pandemic or potential future endemics. They are effectively there since more than 20 years, and protective measures for dentists and clinic personnel should be prioritized in practice, irrespective of the presence of a pandemic, epidemic, normalized conditions, or otherwise.5 Furthermore, these concerns and protective measures should effectively be carried forward through advancements in technologies as well as evidence directed by new knowledge over the years. The current pandemic situation has boosted our thinking and endorsements on how to efficiently manage and minimize aerosol production in contemporary practice.

Evidently, common categories and burdens of orthodontics-related applications producing aerosol and/or airborne particulates are focusing on bonding and debonding strategies. The former involve application of water-spray practices in connection to enamel etching, before conditioning with bonding agents and bracket bonding; the latter pertain to enamel clean-up practices after removal of fixed appliances on completion of orthodontic treatment. Of late, in the line of debonding strategies, an additional procedure liable to aerosol generation has emerged in the clinical field; composite attachment removal after aligner therapy or possible attachment replacement and/or removal cycles during treatment with aligners should not be neglected.6 , 7 This is particularly striking if one considers that most orthodontists and/or other clinicians utilizing aligner methods to straighten teeth and treat malocclusions have adopted wide application of these adjuncts in everyday practice.8 , 9

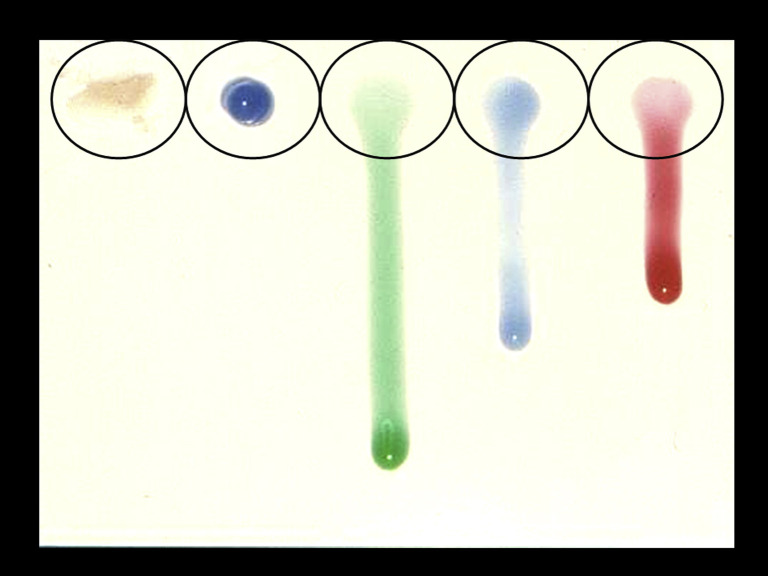

With regard to bonding strategies, the conventional acid-etching stage may be employed with the use of a gel etchant of very thick consistency, a gel of lower viscosity, or a liquid etchant (Fig 1 ). Implications for the first alternative are rather straightforward, as it might require a considerably higher pressure of water flow to be rinsed off, as well as a longer rinsing period; but practically, there is more. Very thick consistencies of gel essentially negate the action of acid for the amount of material not in contact with the enamel surface owing to limited wetting. Thus, the 2 other alternatives are often selected. However, high water pressure used generates splatter, which does not belong to the aerosol classification, but may too contribute to the contamination of the operatory. Water pressure is normally set at 40 PSI in the dental units, with existing air pressure at 80 PSI. The American Dental Association (ADA) has suggested testing of water squirt of more than 1.3 m (∼4 ft), as a practical measure of raised water pressure.10

Fig 1.

Etching agents with variable viscosity. Note the considerably lower viscosity of the green-colored agent, resembling a liquid etchant state. The green, blue (right side) and red agents should be preferred over the first 2, because they would require less water pressure to be rinsed away.

Regarding debonding strategies of fixed appliances, implication of rotary instruments used to remove remnants of composite compounds after fixed appliance removal, as well as utilization of water as cooling agent during handpiece usage form priority factors that should be considered. Cutting efficiency and aerosolized dust formation are also discussed.

This narrative article aims to discuss the hazards arising from routine orthodontic practices implicated to aerosol generation, sometimes on par with and following examples from standard dental procedures, and also to elucidate potential interventions or alterations of conventional orthodontic applications as an attempt to minimize substantial hazards or adverse effects. The narrative is built on 2 basic pillars regarding aerosol generation; the microbiologic on one side, and particulate production and toxicity related implications on the other.

Microbiologic Considerations and Bio-aerosols

The pathogenic pervasiveness of dental aerosol rests in its dependence on the concentration of bacterium or virus load in compressed air, or water-spray spatter mixed-up with tooth material, plaque, blood, calculus, and saliva debris that are theoretically and practically produced during routine dental practice, which makes use of an intraoral service handpiece. As such, orthodontic practices fall within the range of these procedures, seemingly within a more limited extent, but it is important that they are not neglected. The presence of dental unit waterlines (DUWLs) microbiota has also been considered an additional intriguing factor, especially because pathogens get carried forward through the water supply system directly to the handpiece in use.11 When coolants are used during service, the interaction of the cooling agent with fluids and debris produced within the oral environment as a result of composite or tooth grinding practices or use of ultrasonic scaling is present, and inductively, it may be detected in air-suspended particles and aerosol.11 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention12 has established a safety maximum level of colony forming units (CFUs) emitted and detected in the air at the threshold of 500 CFUs per mL as a result of dental handpiece and water and/or air supply instrumentation usage, excluding coliform bacteria for nonsurgical procedures. These levels are liable to reduction when immunocompromised patients are in chair, and are lowered to 200 CFUs per mL. Evaluation of pathogen levels may be done through simple commercially available test strips or kits. In addition, air and/or water related dental instrumentation (handpiece, spray syringe, and/or ultrasonic scaler) in direct usage to patients’ oral cavity should be flushed and pseudotested for 2 minutes at the start of each day, as well as for 30 seconds between patients.13

A recent systematic review on bioaerosols in dental environment has pinpointed the presence of 38 types of micro-organisms, including 19 bacteria and 23 fungal genera, indicating a high variety of a range of species, whereas it was interesting that none of the included articles reported on the presence of viruses or parasites; seemingly, this is not linked to their absence from air-suspended droplets, but rather to the line of focus of the primary studies, partially in favor of the abundance and commonness of the former pathogens and their easier and nonspecific detection through wide air sampling techniques.14 A mean bacterial load range of 1 to 3.9 CFUs in logarithmic scale has been reported after procedural produced aerosol, while the most eminent load has been reported in the range of 1.5 meters from the oral cavity, even higher compared with closer distance measures such as that of 1 meter from the patient.15 Fusobacterium family pathogens have been identified in aerosols produced after ultrasonic scaling in practice through checkerboard DNA–DNA hybridization techniques.16 , 17 Of the family, Fusobacterium nucleatum has been identified as a bacterium related to pathologic, ophthalmic, and respiratory implications, while also inductive of cellular apoptosis in vivo.18 , 19 In addition, it has been reported as related to the launch and progression of periodontitis, or as attenuating attribute of gingival fibroblast mesenchymal cell proliferation.20 However, the results of checkerboard hybridization techniques should be interpreted with caution as per the exact bacteria species eligible for identification, because such practices are close ended, checked in preselected DNA-probe panels and other pathogens not prespecified might be present within droplet spatters as well. Nonetheless, studies assessing mostly periodontal pathogens have identified an increased prevalence of species belonging to the so-called orange complex in aerosols generated during usage of ultrasonic scaler.16 , 17 These mostly pertained to Campylobacter rectus, Prevotella intermedia, and others, including F. periodonticum in addition to F. nucleatum. Apart from directly exposed aerosolized bacteria, another potential contamination source within dental offices or in hospital based dental units has been identified and special attention has been placed to the presence of Legionella pneumophilla as well as Pseudomonas spp in DUWLs.11 , 21 These might well serve as routes of infection for patients and/or dental personnel indirectly and via droplet suspension after aerosol-generating handpiece or water and/or spray syringe usage. Other sources of L. pneumophilla constitute air-conditioning systems or cooling towers within dental settings.14 , 22 Interestingly, the novel SARS-CoV-2 has also been lately reported to demonstrate capacity of emanation via the airflow of air-conditioning units in business environments.23

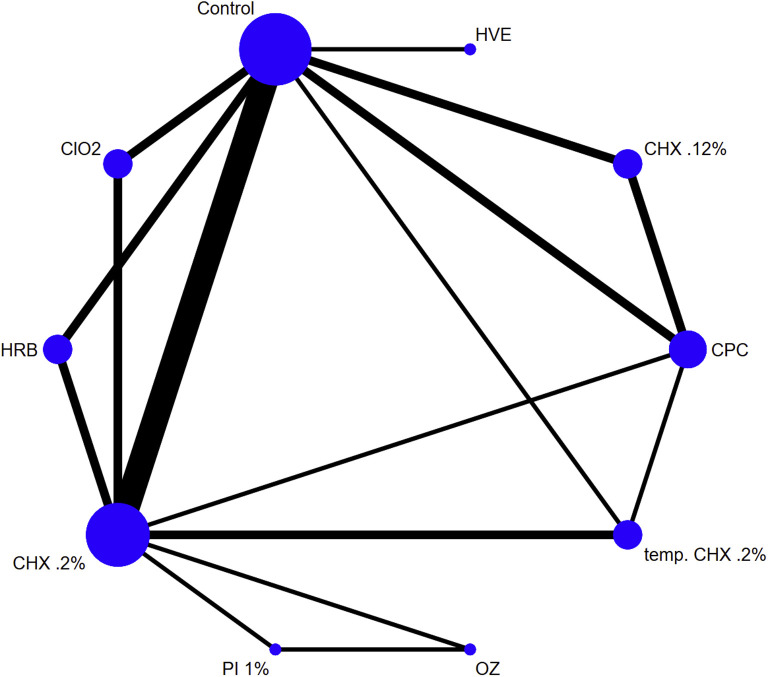

An array of clinical studies, since more than 25 years and until recently, have attempted to identify effective methods of reducing pathogen load stemming from aerosol forming procedures in dental settings (Fig 2 ). The vast majority have studied in-service utilization of ultrasonic scaling, whereas some have reported on orthodontic related strategies of debonding procedures, or other dental prophylaxis or restorative procedures.17 , 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 Largescale efforts have been lately endorsed to collectively appraise all available evidence and provide justifiable ranking of the efficiency of these methods.35 , 36 The most prevalent recorded approaches were preprocedural mouth rinse using a wide variety of potentially antimicrobial agents, such as, chlorhexidine (CHX) 0.12%, CHX 0.2% or tempered CHX 0.2%, cetylpiridinium chloride 0.05%, povidone iodine (PI) 1%, chlorine dioxide, herbal-based agents, or others pertaining to ozone irrigation, use of high volume evacuators and/or dental isolation systems, or agents added to DUWLs to reduce the load.27 , 28 , 37 , 38

Fig 2.

Network map geometry for competing interventions with regard to bacterial load reduction in produced aerosol within dental settings. Size of the node is analogous to the contribution of the sample size for each intervention overall and width of edge to the number of direct comparisons. HVE, high volume evacuator; ClO2, chloride dioxide; HRB, herbal; CPC, cetylpiridinium chloride; OZ, ozone.

Evidence from a study on bacterial load during orthodontic procedures comparing bracket debonding followed by enamel clean-up with high-speed handpiece and water cooling versus standard orthodontic care involving archwire and/or ligature change, and replacing procedures, highlighted the increased pathogenic state of aerosols produced by the former, with a mean difference of 49.2 (95% CI, 19.4–79.0) in total CFUs.31 This highlights the exposure hazards of orthodontists related to certain orthodontic procedures in practice and draws attention to additional prophylactic measures to be selectively taken within the dental operating office. Effectively, bacterial load in aerosol in the dental and/or orthodontic cabinet has shown to be significantly raised immediately within 5 min of service for an aerosol-generating procedure, including enamel clean-up.

Further evidence on microbiologic assessment of aerosol produced after debonding of fixed orthodontic appliances and during composite clean-up has elucidated the increased potential of aerosolized particles, particularly those with aerodynamic diameters of 50 μm or less, to surpass the respiratory barriers and invade deep into the lungs, along with pathogen contaminants.32 , 39 Bioaerosol infiltration has been detected in simulation studies all the way to the respiratory tree from the pharynx to the bronchial alveoli of the lungs. Although decreased particulate size seems to exhibit increased potential to penetrate deep into the lungs, the viability of pathogens has been shown to simultaneously decrease, also impacting biodiversity at the deep respiratory levels.32 , 40

Use of preprocedural mouthrinse with CHX of either 0.12% or 0.2% concentration has been identified by individual studies as an important decontaminating agent contributing to identification of decreased bacterial amounts of infected aerosol; latest data coming from an endorsement to compare all direct and indirect evidence from examined interventions (mouth rinses, evacuators, decontamination of DUWLs, and others) across studies and within dental settings, has revealed this supremacy of preprocedural chlorhexidine mouthrinse over other measures for 30 s to 1 min, but also with documented prevailing of tempered (47°C) CHX 0.2%.27 , 29 , 30 , 35 , 36 , 41 , 42 Tempered CHX solution at 47°C, has been reported to offer increased anti-microbiologic action against bacteria of the human dental plaque, while also preserving adverse effects on tooth and pulp vitality to the minimum.43 The increase in bacterial kill rate has been determined to reach as high as 25% surplus, while to avoid storage contamination with toxic compounds such as p-chloroaniline, freshly made CHX solutions should undergo heating.43 As this measure might be potentially considered impractical for the routine management of clinical practice, it might still be the treatment of choice for highly prone to aerosol induction procedures, with water cooling involvement; other solutions could also be considered for more conservative procedures. Among the priority treatments of choice and apart from CHX solutions (either tempered or nontempered), PI 1% has also been considered a viable alternative.35 , 36

Aforementioned documented evidence originates, as discussed, primarily from ultrasonic scaling clinical studies, randomized in most cases, while total bacterial count in generated aerosol has been the outcome of interest, leaving virus load aside. Extrapolation to other potentially producing aerosolized compounds procedures, however, seems reasonable within a dental cabinet setting and certain orthodontic procedures, such as fixed appliance debonding, may benefit from such measures.

At present and in the middle of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic mid-2020, there is no evidence from clinical trials on the effectiveness of interventions taken preprocedurally in dental offices against viral load in air-suspended droplets or aerosols. However, it would be reasonable to assume that mouth rinses or irrigates with proven capacity to interact with viral molecules and its cellular membranes might prove beneficial. On the basis of the oxidative action of such agents against the lipid membrane of coronaviruses, latest reports as well as primary guidelines of the National Health Commission by the People's Republic of China on measures against SARS-CoV-2, have indicated a decreased effectiveness of chlorhexidine as a measure of choice, mostly because of the lack of oxidative action, while use of hydrogen peroxide 1%, or PI 0.2% to 1% appear more realistic as effective alternatives.44, 45, 46 Oxidative agents act directly on the lipid shell membrane of the virus and destroy cellular components. In particular, PI action is enhanced by the slow and gradual release of iodine as carried by the povidone vehicle, while any adverse effects of iodine are reduced, allowing for a toxicity-free simultaneous interaction.47 Based on the absence of clinical trials in the field of virus load of aerosols, latest calls have emerged and suggest the use of flavonoids or cyclodextrine agents to fight or attenuate SARS-CoV-2 infection through saliva expectorations or spatters secretions.48 However, their effectiveness remains to be tested.

Composite Grinding and Particulate Production

Cutting instrumentation

Composite grinding and particulate production during handpiece instrumentation usage in routine dental practice has been considered an additional source of potentially hazardous concern for dentists and orthodontists in general, but also in particular in the middle of a pandemic of a novel SARS-CoV-2, with unprecedented impact worldwide.1

An initial notion before any consideration of produced aerosolized dust is cutting efficiency and types of dental rotary instruments that might effectively reduce grinding duration. Knowledge on the topic may largely be attributed to the extensive research and work on this field by A.J. von Fraunhofer et al.49, 50, 51, 52, 53

Type of cutting bur and mode of action

First, discrimination between commonly used burs in terms of cutting mechanism is discussed, roughly between 2 of the most prevalent cutting instruments in use, tungsten carbide and diamond burs. The tungsten carbide burs differ from diamond burs, as they are considered to achieve material removal through a flow-dependent fracture process (plastic flow), occurring as a result of elevated shear forces between the carbide blades and the material surface; this makes them rotary instruments of choice for cutting ductile substrates including composites, dentin, or metals. Dissimilarly, diamond cutting burs induce brittle fracture of substrates, functioning by creating grooves and making use of dislocation motion and subsequent radial flow of the material, ultimately leading to propagation of cracks by the generated tensile stresses produced and chip formation. Evidently, diamond burs are mostly efficient for ceramics or enamel surface.49 Latest innovations for adhesive removal after completion of orthodontic treatment, entail the use of fiber-glass or fiber-reinforced composite burs, which have been reported to exhibit a potential for reduced enamel surface roughness on enamel clean-up, compared with standard carbides.54 , 55 However, no data is currently available with respect to the effect of these cutting burs on particulate composite dust dynamic.

Moreover, water supplementation and spray patterns of the handpiece during tooth or material grinding, apart from the straightforward effect on preservation of temperature within tooth and pulpal tolerable standards, have also been implicated as a medium for achieving efficiency during the cutting procedure.56 Water spray during tooth preparation within a proximal value of 40 mL/min room temperature has been considered reasonable for avoiding pulp interactions.56 In reality, water or other lubrication medium has been considered to play a significant role in cutting efficiency following Reynold's hydrodynamic lubrication theory.

In particular, across dental setting environments where standard and known length and material cutting instruments are used for commonly used 400,000 rpm bur rotation speed, it appears unlikely that effects of dynamic viscosity of coolant media may be significant. Testing across water coolant, alcohol (1%) as well as glycerol (2%) solution has revealed comparable effects.49

Further, water application as coolant usage during material grinding in practice, including enamel clean-up from bonding remnants after orthodontic treatment, offer a thin line layer of interproximal matter between the carbide and material interface. This is considered to induce surface adsorption alterations in the substrate material after reduction of the surface-free energy, produced by changes in the strength of association of the interatomic bounds between interactive entities, thus resulting to surface hardness changes.49 To this respect, and as discussed above, cutting with carbide burs in ductile substrates such as resin remnants after debonding of fixed appliances or bonded attachment removal after or during aligner therapy, shall be advantaged, in terms of cutting efficiency, by water supplementation targeted directly to the carbide-composite interface, in the following manner: initial groove formation after bur application is generated, followed by lateral displacement of the substrate, pilling-up material dislocation, and crack propagation, resulting in chip formation.49 The described procedure broadly follows the original work of Rehbinder et al57 back in 1940s, who suggested that chemically-induced surface hardness changes bear the potential to increase drilling efficiency of the cutting tool in mining settings with aqueous surfactant solutions, within a range of 30%-50%. Gain is 2-fold, with subsequent extrapolation to orthodontic and dental practice: faster advancement of the bur into the substrate and decreased demand for heavy load application in practice, thus reduction in operating time and total amount of aerosol production.

Material substrate, composite dust, and aerosol

Resin composites are known to possess a wide range of applications in dentistry, with orthodontics usage in bonding procedures of both fixed appliances as well as treatment with aligners and attachment adjuncts being in the spotlight.58 Normal composite composition comprises of the resin matrix (usually represented by bisphenol-A [BPA] diglycidyl dimethacrylate, triethylene glycol dimethacrylate, and ethoxylated BPA glycol dimethacrylate), the inorganic filler compounds as well as a coupling agent to guarantee bonding between the two.59, 60, 61, 62, 63 Filler compounds usually fall below 0.4 μm and may serve in a wide range of particulate sizes and even fall within the nano-range.62 , 63 Orthodontic adhesives have also been considered to acquire quartz-type filler particles as well.64 Heavy metal oxides are preferred, namely barium, strontium, zinc, aluminum, or zirconium, while their primary service remains to offer enhanced physical and mechanical properties to the material, including polymerization shrinkage water sorption and solubility, radiopacity, and reduction of biodegradation in-service.65, 66, 67, 68

During debonding strategies, but also lately increasingly during attachment removal in the course of and/or after the end of aligner treatment with thermoplastic-type devices, breakdown of the bulk of composites takes place, with material micro- and/or nano-fragments being aerosolized.6 These particulates bear the aerodynamic potential to surpass the respiratory fraction barriers and natural defense mechanisms of the clinician, patient and office personnel and find their way deep into the lungs.69 , 70

A foremost effort to provide evidence in the field of aerosolized composite compounds in dental settings, has been mainly initiated and driven by 2 separately working groups in Leuven, Belgium, and Bristol in the United Kingdom, in essence after simulation in clinical conditions.32 , 64 , 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75 Evidently, aerosols comprising of particles lower than 10 μm or 2.5 μm (PM10 or PM2.5, particulate matter) are gaining attention due to their potential to enter the respiratory tract; interestingly, even smaller particulates within the range of dozens of nanometers (<100 nm) have been associated with an increased dynamic to surpass the primary boundaries of the respiratory system and reach deepest levels of the terminal epithelial bronchioles of the lungs because of their increased surface to volume ratio, offering an amplified reactive potential when in interaction with cellular interfaces.76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82

Several studies have investigated the content compounds of composite dust produced in aerosols in dental and orthodontic setting, and it has been claimed that percentage and concentration of nano-sized identified filler particles in the aerosols might be related to the original filler content of the composites. However, this is far from the case, because all types of composites, irrespective of filler size, have been reported to exhibit significant amounts of nanoparticles within the range of 38-70 nm during grinding and clean-up.64 , 70 , 71 , 73 In particular, surface friction and heating shock during composite grinding results to matrix decomposition of the substrate, aging, C=C conversion of bonds on surface, and ultimately production of respirable composite dust.83, 84, 85

Wet or dry conditions

Apart from water supplementation contribution to the cutting efficiency of grinding tools on the composite substrate during debonding, thus offering minimization of (bio)-aerosol production duration, the effect of water as per emanation, and generation of airborne dust has been disputed, however, with scarce evidence from few research efforts, across variable settings. In essence, a recent study inspected the effect of water cooling in slow-handpiece usage on bulk composite sticks containing an array of filler sizes under simulated conditions of dry and wet grinding.74 Their work suggested consistent findings for all types of composites, which demonstrated a significant reduction in the number of detected nanoparticles being released when water spray was in-service (5.6 × 105 - 13.7 × 105 numbers per cubic centimeter), denoting a half-pace reduction, compared with dry settings. Interestingly though, both dry and wet grinding alternatives produced high numbers of nano-sized particulates being aerosolized overall. The highest amounts have been detected during the last minute of grinding, reaching levels of approximately 33 × 105 numbers per cubic centimeter. Particulate agglomeration has been considered to occur across time, thus contributing in increasing average particulate diameter, overall. To this respect, under water usage conditions, airborne generated nanoparticles have been considered particularly prone to being trapped within water droplets, resulting in increased matter sizes, which are less likely to achieve penetration of the epithelial bronchial barriers and find their way to the lungs.

The aforementioned conditions and settings could be considered as vastly resembling to the bulk attachment material removal during orthodontic treatment with aligners.6 As previously discussed, aligner usage for treatment of malocclusions currently involves increasingly frequent adoption of composite grips bonded to tooth enamel, sometimes more than 1 per tooth, as attachments of various sizes and shapes, with nonnegligible dimensions, varying within the range of 2-5 mm and also width or thickness that may exceed 1 mm.6 , 8 These adjuncts target to the achievement of modes of tooth movement, either rotational or translational, within all 3 planes of space, which would otherwise be non- manageable with the early phase plain thermoplastic aligner usage, that do not necessitate enamel involvement.86 This compares to the thin layer of composites used as a layer of “sandwich-type” pattern between the bracket base and the enamel surface in a conventional case fixed appliance treatment, with an average estimated thickness of 150 to 250 μm; one may evidently cognize that the bulk and thickness of the attachment grips in aligner therapy is implicated in 2 conditions: first, the occurrence of an excessive amount of composite polymerized material within the oral cavity, allowing for the potential risk of BPA release or monomer leaching, depending on the number and shape or size; second, grinding procedures for attachment removal may prove extremely exhaustive and timely, bearing an increasing risk of excessive production of aerosolized composite dust.6 , 59 , 87 , 88

Handpiece role

Furthermore, an earlier report on human extracted teeth and subsequent simulated bracket removal and enamel clean-up, has examined the effect of handpiece, water coolant, and high volume evacuator as well as surgical facemask, on the amount of particulate production and particle concentration during composite grinding after debonding; however, the baseline effect of handpiece was variable, because slow-speed handpiece was used in absence of water coolant, whereas high-speed handpiece only under water-spray emission.75 Findings structured on nonparametric data revealed a significantly higher concentration of airborne particulates under wet conditions and the use of high-speed instrumentation. In addition, use of facemask appeared considerably effective, contributing to the reduction of the detected concentration, while high volume evacuator was not identified as a critical parameter in this respect. To date, there is no further evidence on the direct crude effect of handpiece variation and rotary instrumentation speed with regard to airborne particulate generation, under otherwise comparable conditions.

Cytotoxicity and Estrogenicity of aerosolized particulates

Following research about cytotoxicity and xenoestrogenic effects of BPA and/or monomer release of adhesive compounds within the oral cavity, airborne particulates produced during grinding of composites after fixed appliance removal or aligner's attachment elimination, are seemingly a potential source of similar concerns.88 , 89 A mild but gradual reduction of human bronchial epithelial cell viability in laboratory conditions has been documented, giving rise to speculations on the reactive dynamic of such particulates.62, 63, 64 , 72 Composite filler particles and matrix composition of restorative adhesives did not appear to play a role. Interestingly, the latest report encompassing orthodontic adhesive material evaluation at grinding stages after simulated conventional orthodontic treatment, pinpointed the aptitude of aerosolized particles of adhesives comprising of quartz-type fillers to demonstrate disrupting effects on interacting cell membrane integrity and cellular viability, while also to intervene with cellular growth potential of epithelial bronchial populations at an early stage.64 These effects are probably related to the size and shape of such fillers' configuration, following the increased surface to volume ratio they present.

Related evidence on orthodontic adhesives comes also from the assessment of in vitro estrogenicity of orthodontic composited ground under simulated bonding-debonding settings. Estrogenic effects appear as a result of residual monomer release (BPA), which follows action as an endocrine disruptor because of the very similar structure with beta-estradiol.59 , 90 Under the use of highspeed handpiece without water-spray, eluents containing airborne particulates, after grinding different types of adhesives (ie, chemically or light-cured), have shown an increased proliferating capacity on MCF-7 breast cancer cells in vitro.84

Such findings are of particular interest and raise considerable awareness when it comes to the large-scale removal of attachment grips implicated in aligner therapy. The bulkiness and volume of these adjuncts evidently requires a great amount of grinding efforts and intraoral cutting instrumentation service. It is therefore likely that a significant amount of heat influx occurs first at the surface of the composite substrate if not substantially cooled, resulting in heat shock of the matrix.84 Resultant effects on chemical decomposition of the produced aerosolized dust with further implications on monomer release and BPA diglycidyl dimethacrylate compounds might be alarming.91 , 92 Thus, broad and time-consuming composite removal, as required in extensive removal of attachments, with no water cooling in-service, should largely be avoided, while further research in the field is critical to detect specific effects of water supplementation to the emanation of monomer and other potentially estrogenic compounds.

Implications and recommendations for clinical practice

Direction of measures taken to minimize effects of aerosol production in orthodontic practice should target in 2 basic routes: bonding and debonding procedures, in essence those are interconnected (Table ).

Table.

Recommendations and safety measures to minimize aerosols in orthodontic practice, per procedure

| Procedure | Aerosol-liable actions (conventional) | Safety measures | Future perspectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Etching | |||

| High thickness and/or viscosity gel | Liquid gel and/or low viscosity | Nonetching mediated bonding | |

| Self-etching primer and/or no rinsing | |||

| Glass-ionomer cement and/or no rinsing | |||

| Bonding | |||

| Conventional resin-based adhesive | Glass-ionomer cement | Biomimetic based bonding with use of L-DOPA primers | |

| BPA-free adhesives | |||

| Debonding | |||

| Standard debonding with considerable amounts of adhesive remnants on enamel surface | Alteration of adhesive-bracket base interface | Command-debond adhesives (thermally expandable particles and ferrous micro-particles) | |

| Identify bracket base mesh and/or shape and/or size and adhesive combination for cohesive resin fracture | Irradiation of specific wavelength to reverse polymerization | ||

| Biomimetic bonding agents would eliminate use of rotary instrumentation | |||

| Standard rotary grinding to clean-up enamel | Removal of significant amounts of resin remnants with hand-instruments—avoid rotary instrumentation as much as possible | Temperature control and variation of adhesives (heat and/or freezing) plasticization and/or brittleness | |

| Use of tungsten burs∗ w/o water cooling for limited trace composite remnants (ie, individually debonded brackets during treatment) | |||

| Use of tungsten burs∗, under water cooling for enamel clean-up after debonding and/or attachment removal | |||

| Attachment grips for aligner treatment | Careful selection of patients and/or malocclusions for treatment with aligners; abandon company preset distribution of arrays of attachments | ||

| Attachment-free aligner treatment | |||

| Use of BPA-free composite to eliminate estrogenic activity (ie, PCDMA) | |||

| Preprocedural measures | Mouthrinse with (47°C) CHX 0.12%-0.2% for bacterial pathogens (0.5-1 min) | ||

| Mouthrinse with 0.2%-1% PI or 1% H2O2 for oxidation vulnerable viruses (0.5-1 min) | |||

| Personnel equipment and/or settings | Facemask, shield, gown, apparel for all clinic personnel, and fresh air and surgical suction |

L-DOPA, L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine; w/o, without; PCDMA, phenylcarbamoyloxy-propane dimethacrylate; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide.

Smaller number of flutes in the beginning of removal, advancing to 20-fluted for polishing.

Bonding

The former basically comprises procedures that take place before bracket placement on tooth surface and involve rinsing actions for enamel preparation agents and use of certain types of bonding materials. As previously stated, very thick consistencies and substantial amounts of etchant acid gels applied on tooth surface, apart from presenting compromised action per se, evidently require higher water and/or spray pressure to be rinsed off, thus increasing the likelihood for spatter emanation and droplet formation, but also resulting in prolonged working times. Conventional acid-etching agents entailing low viscosity or even liquid gels should be prioritized. Self-etching primer alternatives have also been proposed, although these may require careful pumicing to ensure a precipitations-free enamel substrate.93 , 94 In the same line and to avoid rinsing application and aerosol production, glass-ionomer cements as compared with conventional light-cured counterparts may be preferred.95 These material alternatives present a chemical interaction and adherence with enamel surface, do not involve prior conventional enamel conditioning, or involve a thin layer of polyacrylic acid agent in contact with enamel, with an induced shallow depth of penetration of approximately 5 to 7 μm.96 They are also less susceptible to moisturized oral cavity conditions, thus offering a viable alternative to classic adhesives bringing the aforementioned advantages, but also bearing a reduced risk for iatrogenic damage to the enamel surface.97 , 98 However, all currently and widely adopted bonding alternatives do not target on the desirable minimization of adhesive remnants covering the enamel surface after debonding.

Starting from the necessity of an enamel-friendly bonding agent, there has been an endorsement and inspiration, following nature and wildlife environment, to design new material structures on par with living creatures' observations. These form the so-called biomimetic materials. For example, gekkonidae lizards (geckos) acquire a unique adhesion ability attributed to their foot pad, the “contact splitting.”99 In particular, geckos' foot pad contains densely packed ultrafine hair, split in the endings, thus offering increased number of contact points per unit area, contributing to greater adhesion forces generated. As such, geckos are capable of sustaining their weight upside-down, with a gravity defying ability, without mediation of any chemical agent, relying only to physical forces, otherwise being impossible to achieve. This type of strong gecko-feet grip has inspired the design of medical adhesives and might attain applicability in orthodontic bonding agents for dry environments.100 Moreover, to overcome failures of geckos' inspired materials, in wet conditions, scientists have studied the use of mussel adhesion as a combination approach, with a resulting new material named “geckel,” which might exhibit enhanced adhesion potential both in dry and wet conditions. Mussel biomimetic polymers are based on L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), offering “sticky” and “glue” resembling properties in the materials.101 In essence, biomimetic based bonding primers such as L-DOPA might offer clinicians a significant tool against oral environment conditions. In combination with geckos’ related properties and applicability to bracket bases, sufficient bond strength to enamel surface might be achieved, without necessitation for prior enamel conditioning, also making debonding practices and enamel clean-up at the end of treatment, effortless.

Debonding

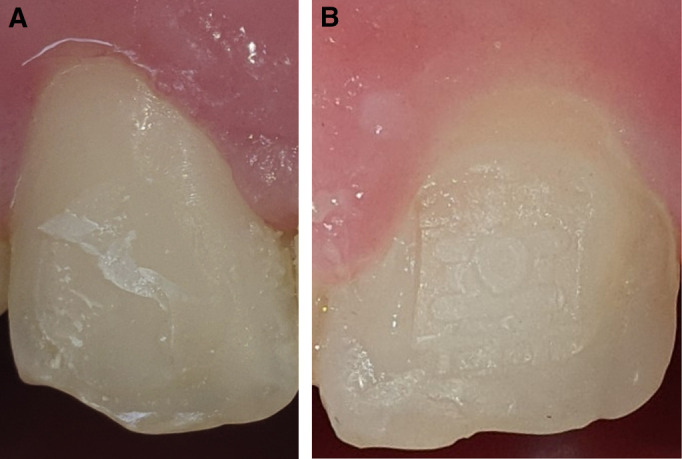

Pertaining to debonding procedures, calls and endorsements for aerosol containment, in general, should be focused first on preventive measures to minimize composite remnants after bracket removal in conventional orthodontics, and second on effective grinding patterns to reduce dust, particulate generation, and operating time, with further speculations on bio-aerosol formation and microbiologic perspectives, as well as xenoestrogenic action of the produced particulate matter. The composite-bracket base interface may play a significant role in achieving a desirable limited amount of adhesive remnant for grinding. Alterations in the adhesive-base interlocking characteristics may take place by induced modifications in the resin filler content and also in the adhesive retention patterns within the bracket base.96 Targeting an efficient combination of bracket base mesh, size, and shape with adhesive composition that may result in a cohesive composite fracture on debonding, would allow for minimal enamel clean-up (Fig 3 ).

Fig 3.

Tooth enamel and composite remnants after bracket debonding: A, cohesive resin fracture with reduced amounts of remnants; B, Adhesive fracture at the bracket base mesh–adhesive interface leaving excessive composite remnants (bracket base mesh impression is evident on the adhesive surface).

In this respect, applications from high technology and automotive industries might offer reformative solutions in orthodontic procedures in the near future. Lately, adhesives that debond on command have been used in interlocking joint positions in technology adjuncts to allow for a temperature-controlled initiation of the debonding process.96 , 102 This is achieved mostly through the embedding of thermally expandable particles (TEMs) into the adhesive matrix.103 The idea about TEMs dates many decades back and resides in the transformation of the particles through heat shock, occurring by softening of the cell particulate matter jointly with gasification of the inner liquid phase hydrocarbon.103 , 104 In the same line, ferrous microparticles within the micron range, have been introduced as fillers and act by being preferentially distributed after external magnet polarity reversal, thus inducing destabilization of the polymer structure and initiating crack states within the resin matrix that may easily be diffused. Other initiatives might also entail application of irradiation to reverse polymerization and produce a highly viscous adhesive state easily to be removed.96

Wide adoption of BPA-free adhesives has been suggested for a range of dentistry applications including orthodontic bracket or fixed retainer bonding.105 To this line, advantages of such alternatives which miss BPA monomer derivatives, have been directed towards the elimination of the reactive oxygen species produced after BPA leaching in the oral cavity, after incomplete polymerization of the adhesives and being able to incite an estrogenic potential. The majority of such alternatives make use of aliphatic co-monomers based on triethyleneglycol dimethacrylate, urethane dimethacrylate, and cycloaliphatic dimethacrylates or are effectively represented by a single aromatic dimethacrylate derivative. These efforts might prove beneficial also with regard to elimination of BPA release in aerosolized dust at the debonding stage.96 , 105

Conclusion

In all, wide and consistent adoption of occupational measures to control generation of aerosol in orthodontic practice should be universal, with microbiologic considerations, particulate matter production as well as toxicity related perspectives being on the spot, even more within the course of a pandemic. Realistic management in practice, should focus on bonding and debonding strategies, while careful selection of procedures and application of safety measures depending on individualized patient needs is fundamental.

In particular, minimization of water-spray syringe utilization for rinsing is anticipated on bonding related procedures, while temporal conditions as represented by seasonal epidemics should be considered for the decision of intervention scheme provided as a procedural mouthrinse, in an attempt to reduce the load of aerosolized pathogens. In normal conditions, CHX 0.2%, preferably under elevated temperature state should be selected for minimization of bacterial load. In the presence and spread of oxidation vulnerable viruses within the community, substitute strategies should be opted, effectively represented by the use of PI 0.2%-1%, or hydrogen peroxide 1%.

After debonding, largescale enamel clean-up strategies should entail the use of carbide tungsten burs under water cooling conditions, to augment cutting efficiency, timely fulfillment of the procedure, as well as reduction of aerosolized nanoparticles. Attachment clean-up at the end of aligner therapy falls into this category; however, selection strategies of malocclusions eligible for aligner treatment should be reconsidered, and a more confined use of attachment grips might also be a viable future perspective. For more limited clean-up procedures, with traces of adhesive remnants left on enamel substrate or individual “re-bracketings” or grinding after bracket breakage in the course of treatment, water cooling rotary instrumentation might not be the treatment of choice, whereas hand-instruments for remnant removal might represent better an effective strategy.

Furthermore, in-office measures of self-protection should never be neglected. Dressing gowns and facemasks with filter protection layers and face shields for all clinic personnel, appropriate ventilation, and fresh air flow within the operating room are of paramount importance. Risk management considerations should be constant but also updated as new material applications come into practice and/or epidemiologic equilibrium of the community is disrupted.

Footnotes

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and none were reported.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Coronavirus situation report. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 Available at:

- 2.Meng L., Hua F., Bian Z. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): emerging and future challenges for dental and oral medicine. J Dent Res. 2020;99:481–487. doi: 10.1177/0022034520914246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang D., Comish P., Kang R. The hallmarks of COVID-19 disease. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008536. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinds W.C. 2nd ed. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken: 1999. Aerosol technology: properties, behavior, and measurement of airborne particles. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter S.R. Infection control in dentistry. Curr Opin Dent. 1991;1:429–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eliades T., Papageorgiou S.N., Ireland A.J. The use of attachments in aligner treatment: analyzing the “innovation” of expanding the use of acid etching-mediated bonding of composites to enamel and its consequences. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020;158:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iliadi A., Koletsi D., Papageorgiou S.N., Eliades T. Safety considerations for thermoplastic-type appliances used as orthodontic aligners or retainers. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical and in-vitro research. Materials (Basel) 2020;13:1843. doi: 10.3390/ma13081843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weckmann J., Scharf S., Graf I., Schwarze J., Keilig L., Bourauel C. Influence of attachment bonding protocol on precision of the attachment in aligner treatments. J Orofac Orthop. 2020;81:30–40. doi: 10.1007/s00056-019-00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai F.F., Xu T.M., Shu G. Comparison of achieved and predicted tooth movement of maxillary first molars and central incisors: first premolar extraction treatment with Invisalign. Angle Orthod. 2019;89:679–687. doi: 10.2319/090418-646.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Infection control recommendations for the dental office and the dental laboratory. ADA council on scientific affairs and ADA council on dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:672–680. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuvo B., Totaro M., Cristina M.L., Spagnolo A.M., Di Cave D., Profeti S. Prevention and control of Legionella and Pseudomonas spp. Colonization in dental units. Pathogens. 2020;9:305. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9040305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2016. Summary of infection prevention practices in dental settings: basic expectations for safe care. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Australian Dental Association . 3rd ed. Australian Dental Association; St Leonards, Australia: 2015. ADA’s guidelines for infection control. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zemouri C., de Soet H., Crielaard W., Laheij A. A scoping review on bio-aerosols in healthcare and the dental environment. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rautemaa R., Nordberg A., Wuolijoki-Saaristo K., Meurman J.H. Bacterial aerosols in dental practice - a potential hospital infection problem? J Hosp Infect. 2006;64:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feres M., Figueiredo L.C., Faveri M., Stewart B., de Vizio W. The effectiveness of a preprocedural mouthrinse containing cetylpyridinium chloride in reducing bacteria in the dental office. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:415–422. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Retamal-Valdes B., Soares G.M., Stewart B., Figueiredo L.C., Faveri M., Miller S. Effectiveness of a pre-procedural mouthwash in reducing bacteria in dental aerosols: randomized clinical trial. Braz Oral Res. 2017;31:e21. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhattacharya S., Livsey S.A., Wiselka M., Bukhari S.S. Fusobacteriosis presenting as community acquired pneumonia. J Infect. 2005;50:236–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang W., Jia Z., Tang D., Zhang Z., Gao H., He K. Fusobacterium nucleatum facilitates apoptosis, ROS generation, and inflammatory cytokine production by activating AKT/MAPK and NF- κ B signaling pathways in human gingival fibroblasts. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:1681972. doi: 10.1155/2019/1681972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang W., Ji X., Zhang X., Tang D., Feng Q. Persistent exposure to Fusobacterium nucleatum triggers chemokine/cytokine release and inhibits the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation capabilities of human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:429. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laheij A.M.G.A., Kistler J.O., Belibasakis G.N., Välimaa H., de Soet J.J., European Oral Microbiology Workshop (EOMW) 2011 Healthcare-associated viral and bacterial infections in dentistry. J Oral Microbiol. 2012;4 doi: 10.3402/jom.v4i0.17659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palusińska-Szysz M., Cendrowska-Pinkosz M. Pathogenicity of the family Legionellaceae. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2009;57:279–290. doi: 10.1007/s00005-009-0035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu J., Gu J., Li K., Xu C., Su W., Lai Z. COVID-19 outbreak associated with air conditioning in restaurant, Guangzhou, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1628–1631. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta G., Mitra D., Ashok K.P., Gupta A., Soni S., Ahmed S. Efficacy of preprocedural mouth rinsing in reducing aerosol contamination produced by ultrasonic scaler: a pilot study. J Periodontol. 2014;85:562–568. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.120616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holloman J.L., Mauriello S.M., Pimenta L., Arnold R.R. Comparison of suction device with saliva ejector for aerosol and spatter reduction during ultrasonic scaling. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jawade R., Bhandari V., Ugale G., Taru S., Khaparde S., Kulkarni A. Comparative evaluation of two different ultrasonic liquid coolants on dental aerosols. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZC53–ZC57. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/20017.8173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshi A.A., Padhye A.M., Gupta H.S. Efficacy of two pre-procedural rinses at two different temperatures in reducing aerosol contamination produced during ultrasonic scaling in a dental set-up - a microbiological study. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2017;19:138–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paul B., Baiju R.M.P., Raseena N.B., Godfrey P.S., Shanimole P.I. Effect of aloe vera as a preprocedural rinse in reducing aerosol contamination during ultrasonic scaling. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2020;24:37–41. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_188_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waghmare S.V., Kini V.V., Srivastava S. Comparative evaluation of colony forming unit count on aerobic culture of aerosol collected following pre-procedural rinses of either 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate or 1% stabilized chlorine dioxide during ultrasonic scaling: a clinical and microbiological study. J Contemp Dent. 2018;8:70–76. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swaminathan Y., Thomas J.T., Muralidharan N.P. The efficacy of preprocedural mouth rinse of 0.2% chlorhexidine and commercially available herbal mouth containing Salvadora persica in reducing the bacterial load in saliva and aerosol produced during scaling. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2014;7:71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toroğlu M.S., Haytaç M.C., Köksal F. Evaluation of aerosol contamination during debonding procedures. Angle Orthod. 2001;71:299–306. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2001)071<0299:EOACDD>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dawson M., Soro V., Dymock D., Price R., Griffiths H., Dudding T. Microbiological assessment of aerosol generated during debond of fixed orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2016;150:831–838. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Logothetis D.D., Martinez-Welles J.M. Reducing bacterial aerosol contamination with a chlorhexidine gluconate pre-rinse. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:1634–1639. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Purohit B., Priya H., Acharya S., Bhat M., Ballal M. Efficacy of pre-procedural rinsing in reducing aerosol contamination during dental procedures. J Infect Prevent. 2009;10:190–192. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koletsi D., Belibasakis G.N., Eliades T. Interventions to reduce aerosolized pathogens in dental practice. A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. https://osf.io/ewph9/ Available at: [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Koletsi D., Belibasakis G.N., Eliades T. Interventions to reduce aerosolized pathogens in dental practice. A systematic review with network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Dent Res. 2020 [Submitted manuscript] doi: 10.1177/0022034520943574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaur S., White S., Bartold P.M. Periodontal disease and rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. J Dent Res. 2013;92:399–408. doi: 10.1177/0022034513483142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mamajiwala A.S., Sethi K.S., Raut C.P., Karde P.A., Khedkar S.U. Comparative evaluation of chlorhexidine and cinnamon extract used in dental unit waterlines to reduce bacterial load in aerosols during ultrasonic scaling. Indian J Dent Res. 2018;29:749–754. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_571_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Micik R.E., Miller R.L., Mazzarella M.A., Ryge G. Studies on dental aerobiology. I. Bacterial aerosols generated during dental procedures. J Dent Res. 1969;48:49–56. doi: 10.1177/00220345690480012401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tham K.W., Zuraimi M.S. Size relationship between airborne viable bacteria and particles in a controlled indoor environment study. Indoor Air. 2005;15(Suppl 9):48–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2005.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shetty S.K., Sharath K., Shenoy S., Sreekumar C., Shetty R.N., Biju T. Compare the effcacy of two commercially available mouthrinses in reducing viable bacterial count in dental aerosol produced during ultrasonic scaling when used as a preprocedural rinse. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2013;14:848–851. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reddy S., Prasad M.G.S., Kaul S., Satish K., Kakarala S., Bhowmik N. Efficacy of 0.2% tempered chlorhexidine as a pre-procedural mouth rinse: a clinical study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:213–217. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.99264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.König J., Storcks V., Kocher T., Bössmann K., Plagmann H.C. Anti-plaque effect of tempered 0.2% chlorhexidine rinse: an in vivo study. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:207–210. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng X., Xu X., Li Y., Cheng L., Zhou X., Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12:9. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Izzetti R., Nisi M., Gabriele M., Graziani F. COVID-19 transmission in dental practice: brief review of preventive measures in Italy. J Dent Res. 2020;99:1030–1038. doi: 10.1177/0022034520920580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Health Commission PRC Guidance for corona virus disease 2019. Prevention, control, diagnosis and management. 5th ed. China: National Health Commission by the People’s Republic of China. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoo J.H. Review of disinfection and sterilization - back to the basics. Infect Chemother. 2018;50:101–109. doi: 10.3947/ic.2018.50.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carrouel F., Conte M.P., Fisher J., Gonçalves L.S., Dussart C., Llodra J.C. COVID-19: a recommendation to examine the effect of mouthrinses with β-Cyclodextrin combined with Citrox in preventing infection and progression. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1126. doi: 10.3390/jcm9041126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.von Fraunhofer J.A., Siegel S.C. Enhanced dental cutting through chemomechanical effects. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:1465–1469. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von Fraunhofer J.A., Siegel S.C., Feldman S. Handpiece coolant flow rates and dental cutting. Oper Dent. 2000;25:544–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siegel S.C., von Fraunhofer J.A. The effect of handpiece spray patterns on cutting efficiency. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:184–188. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siegel S.C., von Fraunhofer J.A. Comparison of sectioning rates among carbide and diamond burs using three casting alloys. J Prosthodont. 1999;8:240–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849x.1999.tb00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siegel S.C., von Fraunhofer J.A. Dental burs--what bur for which application? A survey of dental schools. J Prosthodont. 1999;8:258–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849x.1999.tb00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shah P., Sharma P., Goje S.K., Kanzariya N., Parikh M. Comparative evaluation of enamel surface roughness after debonding using four finishing and polishing systems for residual resin removal-an in vitro study. Prog Orthod. 2019;20:18. doi: 10.1186/s40510-019-0269-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garg R., Dixit P., Khosla T., Gupta P., Kalra H., Kumar P. Enamel surface roughness after debonding: a comparative study using three different burs. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2018;19:521–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ercoli C., Rotella M., Funkenbusch P.D., Russell S., Feng C. In vitro comparison of the cutting efficiency and temperature production of 10 different rotary cutting instruments. Part I: turbine. J Prosthet Dent. 2009;101:248–261. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(09)60049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rehbinder P.A., Wenström E.K. The effect of medium and adsorption layers on plastic flow of metals. Bull Acad Sci USSR ser phys. 1937;4:531–550. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Darvell B.W. 9th ed. Woodhead Publishing Limited; Cambridge: 2009. Materials science for dentistry. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eliades T. Bisphenol A and orthodontics: an update of evidence-based measures to minimize exposure for the orthodontic team and patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;152:435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen M.H. Update on dental nanocomposites. J Dent Res. 2010;89:549–560. doi: 10.1177/0022034510363765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Villarroel M., Fahl N., De Sousa A.M., De Oliveira O.B., Jr. Direct esthetic restorations based on translucency and opacity of composite resins. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2011;23:73–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2010.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iliadi A., Koletsi D., Eliades T., Eliades G. Particulate production and composite dust during routine dental procedures. A systematic review. https://osf.io/st9mx/ Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Iliadi A., Koletsi D., Eliades T., Eliades G. Particulate production and composite dust during routine dental procedures. A systematic review with meta-analyses. Materials (Basel) 2020;13:E2513. doi: 10.3390/ma13112513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cokic S.M., Ghosh M., Hoet P., Godderis L., Van Meerbeek B., Van Landuyt K.L. Cytotoxic and genotoxic potential of respirable fraction of composite dust on human bronchial cells. Dent Mater. 2020;36:270–283. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2019.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ilie N., Hickel R. Investigations on mechanical behaviour of dental composites. Clin Oral Investig. 2009;13:427–438. doi: 10.1007/s00784-009-0258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meyer G.R., Ernst C.P., Willershausen B. Determination of polymerization stress of conventional and new “Clustered” Microfill-Composites in comparison with Hybrid Composites. J Dent Res. 2003;81:921–935. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anusavice K.J., Shen C., Rawls R.H. 12th ed. Elsevier; St Louis: 2013. Phillips’ science of dental materials. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eliades T. Dental materials in orthodontics. In: Graber L.W., Vanarsdall R.L. Jr., Vig K.W.L., Huang G.J., editors. Orthodontics: current principles and techniques. 5th ed. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2012. pp. 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ireland A.J., Moreno T., Price R. Airborne particles produced during enamel cleanup after removal of orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:683–686. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00623-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Van Landuyt K.L., Yoshihara K., Geebelen B., Peumans M., Godderis L., Hoet P. Should we be concerned about composite (nano-)dust? Dent Mater. 2012;28:1162–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Van Landuyt K.L., Hellack B., Van Meerbeek B., Peumans M., Hoet P., Wiemann M. Nanoparticle release from dental composites. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:365–374. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cokic S.M., Hoet P., Godderis L., Wiemann M., Asbach C., Reichl F.X. Cytotoxic effects of composite dust on human bronchial epithelial cells. Dent Mater. 2016;32:1482–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cokic S.M., Duca R.C., Godderis L., Hoet P.H., Seo J.W., Van Meerbeek B. Release of monomers from composite dust. J Dent. 2017;60:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2017.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cokic S.M., Asbach C., De Munck J., Van Meerbeek B., Hoet P., Seo J.W. The effect of water spray on the release of composite nano-dust. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24:2403–2414. doi: 10.1007/s00784-019-03100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johnston N.J., Price R., Day C.J., Sandy J.R., Ireland A.J. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of particulate production during simulated clinical orthodontic debonds. Dent Mater. 2009;25:1155–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hext P.M., Rogers K.O., Paddle G.M. CONCAWE; Brussels: 1999. The health effects of PM2.5 (including ultrafine particles) [Google Scholar]

- 77.Möller W., Häussinger K., Winkler-Heil R., Stahlhofen W., Meyer T., Hofmann W. Mucociliary and long-term particle clearance in the airways of healthy nonsmoker subjects. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2004;97:2200–2206. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00970.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oberdörster G. Pulmonary effects of inhaled ultrafine particles. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2001;74:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s004200000185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Borm P.J.A., Robbins D., Haubold S., Kuhlbusch T., Fissan H., Donaldson K. The potential risks of nanomaterials: a review carried out for ECETOC. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2006;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Napierska D., Thomassen L.C.J., Lison D., Martens J.A., Hoet P.H. The nanosilica hazard: another variable entity. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7:39. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Klaassen C.D. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill; NY: 2008. Casarett and Doull’s toxicology: the basic science of poisons. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schmalz G., Hickel R., van Landuyt K.L., Reichl F.X. Scientific update on nanoparticles in dentistry. Int Dent J. 2018;68:299–305. doi: 10.1111/idj.12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vankerckhoven H., Lambrechts P., van Beylen M., Davidson C.L., Vanherle G. Unreacted methacrylate groups on the surfaces of composite resins. J Dent Res. 1982;61:791–795. doi: 10.1177/00220345820610062801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gioka C., Eliades T., Zinelis S., Pratsinis H., Athanasiou A.E., Eliades G. Characterization and in vitro estrogenicity of orthodontic adhesive particulates produced by simulated debonding. Dent Mater. 2009;25:376–382. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bradna P., Ondrackova L., Zdimal V., Navratil T., Pelclova D. Detection of nanoparticles released at finishing of dental composite materials. Monatsh Chem. 2017;148:531–537. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dasy H., Dasy A., Asatrian G., Rózsa N., Lee H.F., Kwak J.H. Effects of variable attachment shapes and aligner material on aligner retention. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:934–940. doi: 10.2319/091014-637.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kechagia A., Zinelis S., Pandis N., Athanasiou A.E., Eliades T. The effect of orthodontic adhesive and bracket-base design in adhesive remnant index on enamel. J World Fed Orthod. 2015;4:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Eliades T., Voutsa D., Sifakakis I., Makou M., Katsaros C. Release of bisphenol-A from a light-cured adhesive bonded to lingual fixed retainers. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:192–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kloukos D., Sifakakis I., Voutsa D., Doulis I., Eliades G., Katsaros C. BPA qualtitative and quantitative assessment associated with orthodontic bonding in vivo. Dent Mater. 2015;31:887–894. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eliades T., Hiskia A., Eliades G., Athanasiou A.E. Assessment of bisphenol-A release from orthodontic adhesives. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:72–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bettencourt A.F., Neves C.B., de Almeida M.S., Pinheiro L.M., Oliveira S.A., Lopes L.P. Biodegradation of acrylic based resins: a review. Dent Mater. 2010;26:e171–e180. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Atabek D., Aydintug I., Alaçam A., Berkkan A. The effect of temperature on bisphenol: an elution from dental resins. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2014;15:576–580. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pandis N., Polychronopoulou A., Eliades T. Failure rate of self-ligating and edgewise brackets bonded with conventional acid etching and a self-etching primer: a prospective in vivo study. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:119–122. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0119:FROSAE]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fleming P.S., Johal A., Pandis N. Self-etch primers and conventional acid-etch technique for orthodontic bonding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;142:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iliadi A., Baumgartner S., Athanasiou A.E., Eliades T., Eliades G. Effect of intraoral aging on the setting status of resin composite and glass ionomer orthodontic adhesives. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;145:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eliades T. Future of bonding. In: Eliades T., Brantley W.A., editors. Orthodontic applications of biomaterials. A clinical guide. Woodhead Publishing; Cambridge: 2017. pp. 267–271. [Google Scholar]

- 97.McComb D. Luting in orthodontic practice. In: Davidson C., Mjor I.A., editors. Advances in glass-ionomer cements. Carol Stream. Quintessence Publishing; 1999. pp. 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Eliades T. Orthodontic materials research and applications: part 1. Current status and projected future developments in bonding and adhesives. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Berengueres J., Saito S., Tadakuma K. Structural properties of a scaled gecko foot-hair. Bioinspir Biomim. 2007;2:1–8. doi: 10.1088/1748-3182/2/1/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.National Institute of General Medical Sciences Gecko lizard toe hairs inspired the design of medical adhesives. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/education/life-magnified/Pages/9_kunkelgeckofoothairs.aspx#:∼:text=Dennis%20Kunkel%20Microscopy%2C%20Inc.,thickness%20of%20a%20human%20hair.&text=The%20strong%2Dyet%2Dgentle%20grip,for%20use%20on%20delicate%20skin Available at:

- 101.Lee H., Lee B.P., Messersmith P.B. A reversible wet/dry adhesive inspired by mussels and geckos. Nature. 2007;448:338–341. doi: 10.1038/nature05968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Banea M.D., da Silva L.F.M., Carbas R.J.C. Debonding on command of adhesive joints for the automotive industry. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2015;59:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Banea M., da Silva F., Campilho D. An overview of the technologies for adhesive debonding on command. The Annals of “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati. 2013;24:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Morehouse D.S., Jr., Mich M., Tetreault R.J., Mass S. Expansible thermoplastic polymer particles containing volatile fluid foaming agent and method of foaming the same. https://patents.google.com/patent/US3615972A/en Available at: Accessed May 25, 2020.

- 105.Iliadi A., Eliades T., Silikas N., Eliades G. Development and testing of novel bisphenol A-free adhesives for lingual fixed retainer bonding. Eur J Orthod. 2017;39:1–8. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjv090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]