Abstract

Background: We used 18F-sodium fluoride (NaF) to assess early atherosclerosis in the global heart in asymptomatic individuals with a coronary calcium score of zero and without a formal diagnosis of hypertension. We hypothesized that these individuals might present with subclinical atherosclerosis that correlates with systolic, diastolic and mean arterial pressure (SBP, DBP, and MAP). Methods: We identified 20 asymptomatic individuals (41.6 ± 13.8 years, 8 females) from the CAMONA trial with C-reactive protein ≥3 mg/L, no smoking history, diabetes (fasting blood glucose <126 mg/dl) and dyslipidemia per the Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines: untreated LDL <160 mg/dL, total cholesterol <240 mg/dL, HDL >40 mg/dL. All underwent PET/CT imaging 90 minutes after NaF injection (2.2 Mbq/Kg). The global cardiac average SUVmean (aSUVmean) was calculated for each individual. Correlation coefficients and linear regression models were employed for statistical analysis. Results: Significant positive correlation was revealed between global cardiac NaF uptake and all blood pressures: SBP (r=0.44, P=0.05), DBP (r=0.64, P=0.002), and MAP (r=0.59, P=0.007). After adjusting for age and gender, DBP and MAP were independent predictors of higher global cardiac NaF uptake. Conclusion: NaF-PET/CT for detecting and quantifying subclinical atherosclerosis in asymptomatic individuals revealed that cardiac NaF uptake correlated independently with DBP and MAP.

Keywords: Subclinical atherosclerosis, dyslipidemia, blood pressure, coronary calcium, NaF

Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and death worldwide [1]. Atherosclerosis is a progressive, systemic inflammatory process with a long asymptomatic phase which can potentially manifest in clinical disease depending on the extent and vascular territory involved. Several risk factors, such as age, gender, smoking, dyslipidemia, diabetes and hypertension are strongly associated with the development of atherosclerosis [2,3].

Population based risk assessment tools utilize traditional cardiovascular risk factors and are widely used for early identification of high risk asymptomatic individuals, allowing for appropriate management to prevent major adverse cardiovascular events [4]. Presence of coronary artery calcium is highly prevalent in coronary heart disease and its detection and quantification by cardiac CT is clinically useful in identifying subclinical coronary atherosclerosis and risk stratify individuals [5,6]. Coronary artery calcium can also be detected by magnetic resonance and molecular imaging [7]. Recently, molecular imaging with positron emission tomography (PET) and 18F-sodium fluoride (NaF) has increased our understanding of the mechanisms involved in atherosclerosis, particularly in the detection of subclinical disease. In the arterial wall, NaF selectively adsorbs to the surface of crystals of calcium hydroxyapatite by exchanging with hydroxyl ions to form fluoroapatite [8-10].

Elevated blood pressure represents a major modifiable risk factor of atherosclerosis [11]. We aimed to detect and quantify global coronary artery microcalcification as a marker of coronary atherosclerosis in asymptomatic individuals without detectable macroscopic calcification on cardiac CT. We hypothesized that the burden of coronary atherosclerosis is directly related to the level of blood pressure in the absence of risk factors such as dyslipidemia, diabetes and smoking.

Methods

Subjects

This study was conducted in a subset of asymptomatic subjects from the prospective study known as “Cardiovascular Molecular Calcification Assessed by 18F-FDG PET/CT (CAMONA)” in Odense, Denmark. The CAMONA study was approved by the Danish National Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics as well as registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01724749) [12]. The study was undertaken in concordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all subjects provided written informed consent. The subjects in this population were excluded based on the presence of malignancy, immunodeficiency syndrome, autoimmune disease, pregnancy, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, endocarditis, symptoms suggestive of cardiovascular disease such as syncope, chest pain, and shortness of breath, as well as use of prescription medications.

In this cohort, we identified 20 subjects (41.6 ± 13.8 years, 8 females, 12 males) who met our pre-defined criteria: no formal diagnosis of hypertension or use of antihypertensive medication, no smoking history, no diabetes (fasting plasma glucose <126 mg/dL), no dyslipidemia as per the Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines: LDL <160 mg/dL, total cholesterol <240 mg/dL, HDL >40 mg/dL, non-inflammatory state defined by C-reactive protein <3 mg/L and coronary artery calcium score (CAC) of zero [13]. Patients who did not meet this pre-defined criterion were excluded (current or past use of antihypertensive medication for blood pressure control, positive history of smoking or diabetes [fasting plasma glucose >126 mg/dL], presence of dyslipidemia [LDL >160 mg/dL, total cholesterol >240 mg/dL, HDL <40 mg/dL], presence of inflammatory state [C-reactive protein >3 mg/dL], and CAC score of >0). Baseline characteristics were recorded (Table 1). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured as baseline characteristics prior to the acquisition of PET scans. After 5 minutes of rest in a supine position, blood pressure was recorded three times by an automatic device. The last two values were averaged for the study. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated by taking the sum of two-thirds of diastolic pressure and one-third of systolic pressure. These individuals were further divided into hypertensive (SBP ≥130 mm Hg or DBP ≥80 mm Hg) and non-hypertensive (SBP <130 mm Hg and DBP <80 mm Hg) categories as per current 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines on high blood pressure [14].

Table 1.

Subject demographics

| Demographics | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age | 41.6 ± 13.8 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 125.1 ± 14.9 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 72.7 ± 9.4 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 90.2 ± 10.7 |

| Low density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 2.8 ± 0.8 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.6 ± 0.8 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 0.8 ± 0.3 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.5 ± 0.4 |

| Plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 5.4 ± 0.5 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 32.3 ± 3.5 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.3 ± 0.6 |

Note: HbA1c = Glycated hemoglobin. N=20.

Quantitative image analysis

All subjects underwent NaF PET/CT imaging with an established and uniform protocol (GE Discovery STE, VCT, RX, and 690/710). Patients were made to observe an overnight fast of 6 hours and a blood glucose measurement ensuring a concentration below 8 mmol/L. NaF-PET/CT imaging was performed 90 minutes following administration of 2.2 MBq of NaF per kilogram of body weight. These images were produced using one of several PET/CT systems (GE Discovery STE, VCT, RX, and 690/710). PET images were corrected for attenuation, scatter, scanner dead time, and random coincidences. Low-dose CT imaging (140 kV, 30-110 mA, noise index 25, 0.8 seconds per rotation, slice thickness 3.75 mm) was performed for attenuation correction and anatomic referencing with PET images.

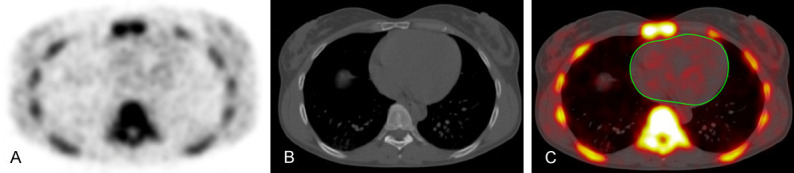

Quantification of global cardiac NaF uptake was performed by a trained physician who manually defined a region of interest (ROI) around the cardiac silhouette on each axial PET/CT slice using a DICOM viewer (Osirix MD Software; Pixmeo SARL, Bernex, Switzerland) (Figure 1). The ROI did not include any parts of the skeleton, cardiac valves, or aortic wall. The application of global assessment to study atherosclerotic microcalcification in the coronary arteries utilizing NaF has been established in previous studies [15-17]. For every ROI, representing the volume of one cardiac slice, the NaF activity was determined as the mean standardize uptake value. Then, these values were added and divided by the sum of the ROI-defined slice volumes to yield a global cardiac average mean standardize uptake value (aSUVmean).

Figure 1.

Axial NaF-PET (A), CT (B), and fused NaF-PET/CT (C) images with region of interest in a healthy subject (C). The manually-delineated region of interest determined the global coronary artery NaF uptake and did not include uptake from the aortic valve, skeletal structures, and aortic wall.

Statistical analysis

The association between blood pressure and the aSUVmean of the whole heart was evaluated. The global cardiac aSUVmean between the non-hypertensive and hypertensive groups were compared using nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to determine the value of global cardiac aSUVmean of NaF to distinguish the burden of microcalcification between hypertensive (SBP ≥130 mm Hg or DBP ≥80 mm Hg) and non-hypertensive subjects (SBP <130 mm Hg and DBP <80 mm Hg). Pairwise correlations were assessed with correlation coefficients. Linear regression analyses adjusting for age and gender were performed to understand the independent association of SBP, DBP and MAP with the mean NaF uptake of the global heart (global cardiac aSUVmean). Box plots and scatter plots (including regression lines with 95% confidence bands) were generated to help with visualization of data. A p value <0.05 was chosen as being statistically significant. We used Statistical software packages SPSS (Version 25.0, IBM) and STATA/MP 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas 77845 USA) for the statistical analysis and generating figures.

Results

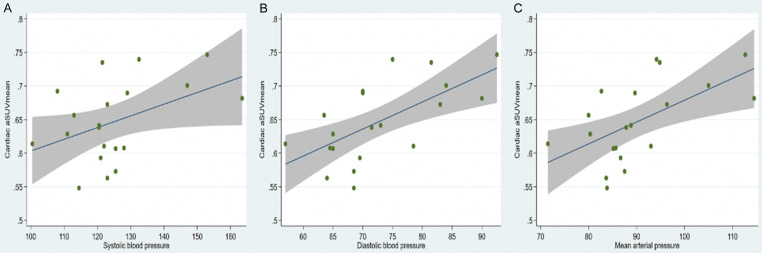

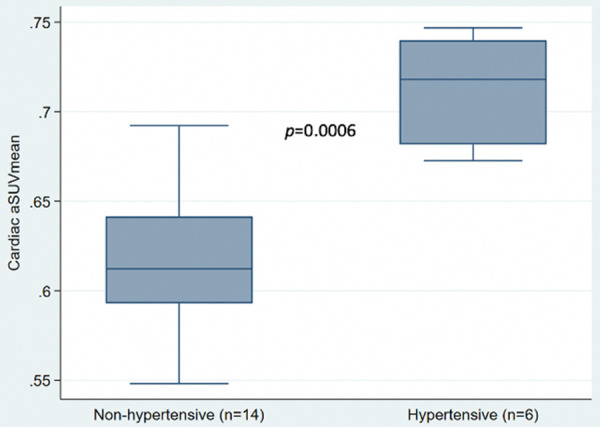

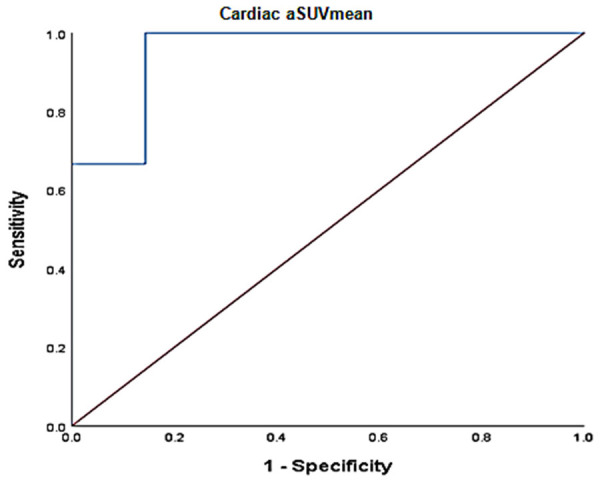

Correlation analysis revealed a robust positive relationship between global cardiac aSUVmean and individual blood pressure measurements: SBP (r=0.44, P=0.05), DBP (r=0.64, P=0.002), and MAP (r=0.59, P=0.007) (Figure 2). Global NaF uptake (cardiac aSUVmean ± SD) was lower in the non-hypertensive group (n=14), compared to hypertensive group (n=6): 0.62 ± 0.043 vs. 0.71 ± 0.04, respectively, p=0.0006 (Figure 3). On ROC curve analysis, a cardiac aSUVmean value of 0.6646 had 100% sensitivity and 85.7% specificity (AUC: 0.952 ± 0.045, 95% CI: 0.864-1.0, P=0.002) in distinguishing hypertensive from non-hypertensive subjects in the study cohort (Figure 4). On multivariable regression analysis adjusted for age and gender, DBP (β=0.003, 95% confidence interval: 0.0009 to 0.006, P=0.011; adjusted R2: 0.43) and MAP (β=0.003, 95% confidence interval: 0.0004 to 0.005, P=0.025; adjusted R2: 0.37) were independent predictors of global cardiac aSUVmean, but SBP was not (β=0.001, 95% confidence interval: -0.0004 to 0.003, P=0.12; adjusted R2: 0.26).

Figure 2.

Correlations between cardiac aSUVmean and (A) Systolic, (B) Diastolic, and (C) Mean Arterial Pressure. Significant correlations were present in all three pressures.

Figure 3.

Box plot comparing Cardiac aSUVmean of non-hypertensive and hypertensive subjects. Wilcoxon rank sum test comparing the two groups revealed a p-value of 0.0006.

Figure 4.

ROC curve analysis of Cardiac aSUVmean and hypertension (AUC: 0.952 ± 0.045, 95% CI: 0.864-1.0, P=0.002).

Discussion

In asymptomatic individuals without a known diagnosis of hypertension and absence of other risk factors like diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking and systemic inflammatory state, Na-F PET/CT was able to identify a higher burden of global coronary microcalcification in a subgroup with higher blood pressures. Furthermore, our results revealed that individually measured SBP, DBP and MAP correlated positively with the extent of global coronary atherosclerosis as quantified by Na-F PET/CT. However, after adjusting for age and gender, only DBP and MAP were independently indicative of an increased global coronary atherosclerotic burden. A possible explanation for the latter finding could be the fact that coronary flow occurs mainly in diastole and that the mean arterial pressure is dependent on the diastolic blood pressure. The higher blood pressures during diastole induce increased mechanical and oxidative stress on the arterial wall, potentially resulting in greater atherosclerotic plaque formation and progression [18-20]. Over time, these plaques undergo a series of progressive changes, one of which is microcalcification. The pathophysiological process responsible for vascular calcification involves the release of specific pro-inflammatory cytokines by macrophages present in the atheromatous plaques that lead to osteogenic differentiation. The resulting deposition of calcium microcrystals further stimulates the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from the macrophages, leading to a self-propagating cycle [21].

Prior studies have sought to examine the relationship between blood pressure and coronary atherosclerosis. A study consisting of 285 individuals receiving statin therapy for stable coronary artery disease underwent CT angiography to study the total coronary plaque burden. They found that the coronary plaque volume was greater with increasing levels of diastolic pressures. In comparison, systolic pressures were not found to predict the coronary plaque volume [22]. Using an electron beam computed tomography, The Rochester Family Heart Study examined the association of systemic pressures with coronary calcification and found that, after adjusting for age and sex, ambulatory measurements of systolic and diastolic blood pressures were predictive of coronary arterial calcification. However, further adjustment for office blood pressure revealed that only diastolic pressure was a true independent predictor of coronary arterial calcification and systolic pressure was not. Furthermore, this study established that hypertension was in fact the most influential independent risk factor for coronary arterial calcification, more important than hyperlipidemia and diabetes [23]. In a multivariate analysis conducted in the Muscatine study of 384 individuals, DBP was found to independently predict coronary arterial calcification in those aged 29-37 years whereas LDL-C and SBP did not [24]. Another study utilizing intravascular ultrasound to examine atheroma burden in 330 patients found that baseline diastolic pressures independently predicted an increase in the percentage of atheroma volume at a 1-year follow up [25].

The severity of atherosclerotic burden assessed by the measurement of the coronary artery calcium via computed tomography has been utilized extensively and found to be very useful in clinical decision making, primarily in risk stratification and prognostication of asymptomatic individuals [5,6]. Our study highlights the feasibility of using molecular imaging, particularly Na-F PET/CT, in understanding the complex pathophysiology of subclinical atherosclerosis in individuals with CAC score of zero. The clinical role of Na-F PET/CT in detecting global coronary artery molecular calcification has yet to be clearly established in guidelines as this technique has been used primarily for investigational purposes.

Limitations of our study were the small sample size and the suboptimal condition under which these blood pressures were measured, i.e., in the interval between tracer injection and PET/CT acquisition. Thus, our findings are mainly hypothesis generating. A larger sample size and controlled blood pressure circumstances are required to further characterize the relationship of global coronary microcalcification with blood pressure. Also, our findings need to be interpreted in the context of the absence of dyslipidemia as defined in our study and results may vary based on different lipid thresholds.

In conclusion, higher resting diastolic blood pressure and mean arterial pressure are associated with greater burden of coronary atherosclerosis in the absence of risk factors like smoking, dyslipidemia and diabetes.

Acknowledgements

The Jørgen and Gisela Thrane’s Philanthropic Research Foundation, Broager, Denmark, financially supported the CAMONA study.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Herrington W, Lacey B, Sherliker P, Armitage J, Lewington S. Epidemiology of atherosclerosis and the potential to reduce the global burden of atherothrombotic disease. Circ Res. 2016;118:535–546. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libby P, Bornfeldt KE, Tall AR. Atherosclerosis: successes, surprises, and future challenges. Circ Res. 2016;118:531–534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajar R. Risk factors for coronary artery disease: historical perspectives. Heart Views. 2017;18:109. doi: 10.4103/HEARTVIEWS.HEARTVIEWS_106_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace ML, Ricco JA, Barrett B. Screening strategies for cardiovascular disease in asymptomatic adults. Prim Care. 2014;41:371–397. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budoff MJ, Gul KM. Expert review on coronary calcium. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:315–24. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenland P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Erbel R, Watson KE. Coronary calcium score and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:434–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Osborne MT, Tung B, Li M, Li Y. Imaging cardiovascular calcification. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008564. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitagawa T, Yamamoto H, Toshimitsu S, Sasaki K, Senoo A, Kubo Y, Tatsugami F, Awai K, Hirokawa Y, Kihara Y. 18F-sodium fluoride positron emission tomography for molecular imaging of coronary atherosclerosis based on computed tomography analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2017;263:385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derlin T, Richter U, Bannas P, Begemann P, Buchert R, Mester J, Klutmann S. Feasibility of 18F-sodium fluoride PET/CT for imaging of atherosclerotic plaque. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:862–865. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.076471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irkle A, Vesey AT, Lewis DY, Skepper JN, Bird JL, Dweck MR, Joshi FR, Gallagher FA, Warburton EA, Bennett MR, Brindle KM, Newby DE, Rudd JH, Davenport AP. Identifying active vascular microcalcification by 18F-sodium fluoride positron emission tomography. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7495. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Rodgers A International Society of Hypertension. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371:1513–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blomberg BA, de Jong PA, Thomassen A, Lam MGE, Vach W, Olsen MH, Mali WPTM, Narula J, Alavi A, Høilund-Carlsen PF. Thoracic aorta calcification but not inflammation is associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk: results of the CAMONA study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:249–258. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3552-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:e127–e248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moghbel M, Al-Zaghal A, Werner TJ, Constantinescu CM, Hoilund-Carlsen PF, Alavi A. The role of PET in evaluating atherosclerosis: a critical review. Semin Nucl Med. 2018;48:488–497. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorci O, Batzdorf AS, Mayer M, Rhodes S, Peng M, Jankelovits AR, Hornyak JN, Gerke O, Høilund-Carlsen PF, Alavi A, Rajapakse CS. 18F-sodium fluoride PET/CT provides prognostic clarity compared to calcium and Framingham risk scoring when addressing whole-heart arterial calcification. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:1678–1687. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04590-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blomberg BA, Thomassen A, de Jong PA, Lam MGE, Diederichsen ACP, Olsen MH, Mickley H, Mali WPTM, Alavi A, Høilund-Carlsen PF. Coronary fluorine-18-sodium fluoride uptake is increased in healthy adults with an unfavorable cardiovascular risk profile: results from the CAMONA study. Nucl Med Commun. 2017;38:1007–1014. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramanathan T, Skinner H. Coronary blood flow. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2005;5:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madamanchi NR, Vendrov A, Runge MS. Oxidative stress and vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:29–38. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000150649.39934.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhawan SS, Avati Nanjundappa RP, Branch JR, Taylor WR, Quyyumi AA, Jo H, McDaniel MC, Suo J, Giddens D, Samady H. Shear stress and plaque development. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;8:545–56. doi: 10.1586/erc.10.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demer LL, Tintut Y. Vascular calcification: pathobiology of a multifaceted disease. Circulation. 2008;117:2938–2948. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saleh M, Alfaddagh A, Elajami TK, Ashfaque H, Haj-Ibrahim H, Welty FK. Diastolic blood pressure predicts coronary plaque volume in patients with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2018;277:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner ST, Bielak LF, Narayana AK, Sheedy PF, Schwartz GL, Peyser PA. Ambulatory blood pressure and coronary artery calcification in middle-aged and younger adults. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:518–524. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(02)02271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahoney LT, Burns TL, Stanford W, Thompson BH, Witt JD, Rost CA, Lauer RM. Coronary risk factors measured in childhood and young adult life are associated with coronary artery calcification in young adults: the muscatine study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:277–284. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García-García HM, Klauss V, Gonzalo N, Garg S, Onuma Y, Hamm CW, Wijns W, Shannon J, Serruys PW. Relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and biomarkers with necrotic core and atheroma size: a serial intravascular ultrasound radiofrequency data analysis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;28:695–703. doi: 10.1007/s10554-011-9882-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]