The national initiative “Healthy People 2020”1 prominently features the aspirational goal to create social and physical environments that promote good health for all, including persons from minorities as one of the four overarching goals for the decade. However, Americans from racial and ethnic minorities face persistent and pervasive health disparities at all stages of the life cycle and especially so in the last years of life. Although culturally competent care is a vital element of all health care, it becomes critically important in the care of the seriously ill.

Data1–4 for the past two decades have consistently shown that persons from minority groups are less likely to complete advance directives, less access palliative and hospice services, more likely to revoke hospice care, and their families are more likely to report poor satisfaction with care. We are currently at an inflexion point as our nation is poised to become a minority–majority nation. Culture influences how patients and families interpret, understand, and experience pain and illness, and how they respond to palliative interventions. Attentiveness to cultural3–6 beliefs and behaviors must be a core and central element in the delivery of services to seriously ill patients.

As health professionals, we have one of two choices. We could hope and hold on to a clinical pipedream and wait for millions of minority Americans to relinquish their cultural beliefs and obediently embrace mainstream palliative and hospice care. Or we can make strident efforts toward providing culturally competent care and culturally and linguistically adapt palliative care therapeutic measures as exemplified by the work of Costas-Muñiz et al. in this issue of Journal of Palliative Medicine (page 489).

To provide culturally humble respectful care for all seriously ill patients and their families, we need to attend to cultural competence both at the individual level and at the organizational level.

Individual Level

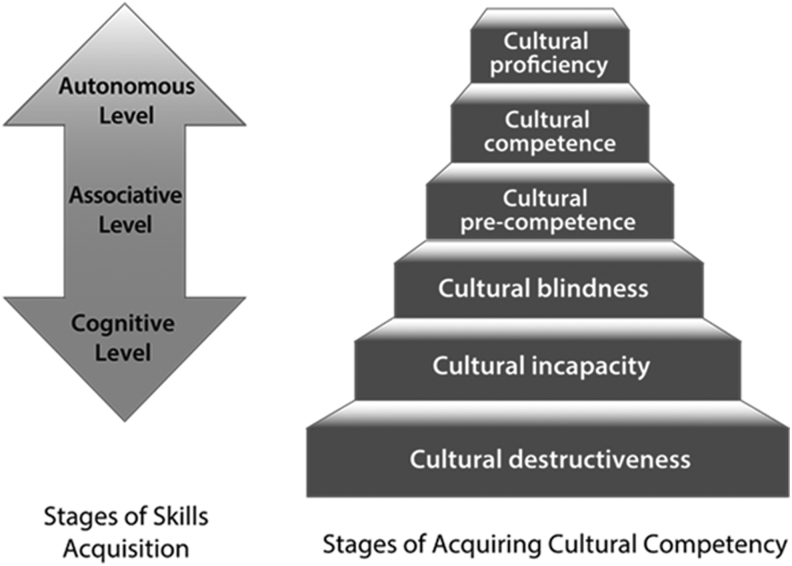

Cultural competence training is of paramount importance for all persons caring for seriously ill patients and families. Acquisition of skills related to cultural humility and respectful care is a developmental process with three stages that exist along a spectrum (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Stages of skill acquisition. Stages of acquiring cultural competency.

Stage 1: The cognitive stage of skill acquisition: This is an early stage in the learning trajectory. Individuals at this stage are inconsistent in their skills and are likely to make frequent errors and require ongoing redirection and feedback.

Stage 2: The associative stage of skill acquisition: At this stage, the individual has acquired some basic skills. This is a lengthy stage and is characterized by the need for ongoing practice and self-reflection to become more skilled. As the individual progresses in the skill continuum, errors become smaller in magnitude and frequency.

Stage 3: The autonomous stage of skill acquisition: At this stage, the individual is fluent and at ease in providing culturally competent respectful care. The magnitude and frequency of errors become lesser as they advance in the skill continuum.

It is to be noted that ongoing practice and self-reflection are key to maintaining the level of skills. Infrequent practice will result in regression of skills.

Organizational Cultural Competency Framework

Building culturally competent health care organizations is an iterative developmental process that requires ongoing engagement of leaders and stakeholders at multiple levels. Health care organizations usually exist in a continuum7 of developmental stages ranging from cultural destructiveness to cultural proficiency as described hereunder. Organizations can stay static, progress, or regress through these developmental stages based on their values and behaviors. Also different parts of the organization can exist at any of the six stages described as follows:

-

1.

Cultural destructiveness: Cultural destructiveness is the exhibition of bigotry in thought, word, or deed. These organizations demonstrate and condone disrespect and biased treatment of persons from minority and disadvantaged backgrounds.

-

2.

Cultural incapacity: The organization fears or ignores the unique needs of persons from minority and disadvantaged backgrounds. They exhibit discrimination in their policies and hiring practices.

-

3.

Cultural blindness: The organization functions with the belief that color or culture makes no difference. They choose to believe that the needs of all people are the same and all have equitable access to resources. They implicitly suppress individuality and promote conformity to the majority group's beliefs and behaviors.

-

4.

Cultural precompetence: The precompetent organization realizes its weaknesses in serving persons from minority groups and those from disadvantaged backgrounds. These organizations desire to deliver quality services to diverse populations and make attempts to improve some aspects of their services. For example, they may have a workgroup that deliberately focuses on increasing organizational cultural competence. They may demonstrate a commitment to follow national standards best practices such as the CLAS8 standards.

-

5.

Cultural competence: Culturally competent organizations expect, accept, and respect individual differences. They recognize that minority groups are heterogeneous with numerous subgroups, each with important cultural characteristics. They also understand that persons from minority and disadvantaged backgrounds have encountered barriers to accessing resources and experienced biases and microaggressions.9 These organizations conduct ongoing self-assessment of how they are providing services to diverse populations and adapt service models to best meet the unique needs of persons from all groups and populations.

-

6.

Cultural proficiency: Culturally proficient organizations serve as role models to other organizations. They work to (a) expand the knowledge base of culturally competent practice by conducting ongoing research, and (b) implement and evaluate new approaches that incorporate and celebrate personalized care for individuals from all cultural backgrounds.

Both individual and organizational efforts are required to ensure that we provide culturally tailored palliative care to all seriously ill patients and families.

References

- 1. Secretary's Advisory Committee on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020: Healthy People 2020: An Opportunity to Address the Societal Determinants of Health in the United States. www.healthypeople.gov/2010/hp2020/advisory/SocietalDeterminantsHealth.htm

- 2. Internet Reference. 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health#one

- 3. Periyakoil VS: Building a culturally competent workforce to care for diverse older adults: Scope of the problem and potential solutions. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(S2):S423–S432. Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, et al.: The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med 2003;67(S2):277–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Batalova J, Zong J: Language Diversity and English Proficiency in the United States. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2016. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/language-diversity-and-english-proficiency-united-state [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robinson KM, Monsivais JJ: Acculturation, depression, and function in individuals seeking pain management in a predominantly Hispanic southwestern border community. Nurs Clin North Am 2011;46:193–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pescosolido BA, Medina TR, Martin JK, Long JS: The “backbone” of stigma: identifying the global core of public prejudice associated with mental illness. Am J Public Health 2013;103:853–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cross T, Bazron B, Dennis K, Isaacs M: Towards a Culturally Competent System of Care, Volume I. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Child Development Center, CASSP Technical Assistance Center, 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 8.https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/clas/

- 9. Periyakoil VS, Chaudron L, Hill EV, et al. : Common types of gender-based microaggressions in medicine. Acad Med 2019. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]