Abstract

Background: Casarett et al. tested an intervention to improve timeliness of referrals to hospice. Although efficacious in the nursing home setting, it was not tested in other settings of care for seriously ill patients. We, therefore, adapted Casarett's intervention for use in home health (HH).

Objective: To assess feasibility, acceptability, and patient outcomes of the adapted intervention.

Design: We conducted a nine-week observational pilot test.

Setting/Subjects: We conducted our pilot study with two HH agencies. Eligible patients included those who were high risk or frail (identified by the agencies' analytic software as being moderate to high risk for hospitalization or a candidate for hospice referral). Clinical managers identified eligible patients and registered nurses then delivered the intervention, screening patients for hospice appropriateness by asking about care goals, needs, and preferences and initiating appropriate follow-up for patients who screened positive.

Measurements: We collected quantitative data on patient enrollment rates and outcomes (election of hospice and/or palliative care). We collected qualitative data on pilot staff experience with the intervention and suggestions for improvement.

Results: Pilot HH agencies were able to implement the intervention with high fidelity with minimal restructuring of workflows; 14% of patients who screened positive for hospice appropriateness elected hospice or palliative care.

Conclusions: Our findings suggest the adapted intervention was feasible and acceptable to enhance timeliness of hospice and palliative care referral in the HH setting. Additional adaptations suggested by pilot participants could improve impact of the intervention.

Keywords: hospice, palliative care, referrals to hospice palliative care

Background

Hospice care offers benefits to terminally ill patients, including improved quality of life and decreased symptom burden.1,2 Despite this, fewer than half of Medicare decedents die on hospice services.3 Furthermore, the median length of stay for those who do use hospice is 24 days, falling short of the expert-recommended three months.3–5 A primary reason for underutilization is delayed referrals by the physician who determines the terminal prognosis; physicians may be hesitant to refer seriously ill patients to hospice for fear of bringing up hospice “too early,” lack of training in compassionate discussion of bad news, and difficulty in accurately predicting a prognosis of six months or less.6–9 Patient-level factors also present barriers. Misunderstanding what end-of-life care comprises is common, and patients/families may be overly optimistic in estimating prognosis, wishing to continue curative treatment, and denying terminal prognosis.6,7,9,10

Methods

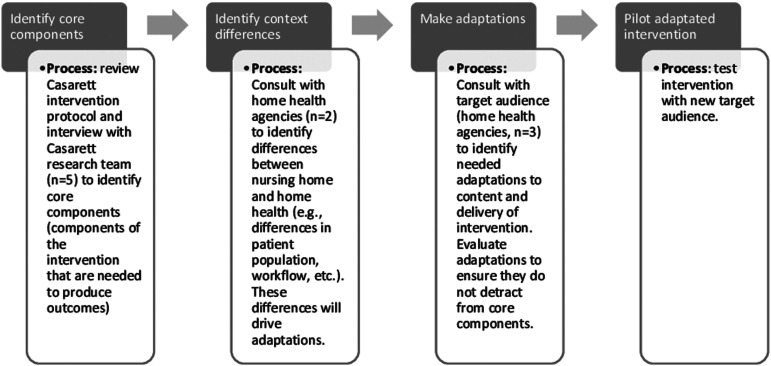

To improve hospice referrals, an intervention developed by Casarett et al. for nursing home residents was adapted for use in home health (HH).11 Casarett et al. originally tested the intervention in a randomized controlled trial where research staff carried out intervention activities; although efficacious, the intervention was not widely adopted in practice. We adapted the intervention following guidance in the Planned Adaptation Model,12 engaging relevant stakeholders (Casarett research team and HH agencies) (Fig. 1). We retained much of the content of Casarett et al.'s intervention (a screening intervention where patients were asked about care goals, needs, and preferences). Major adaptations included changing (1) eligibility criteria to make the intervention more appropriate for HH patients (we screened only high-risk or frail patients) and (2) intervention delivery to improve generalizability (we adapted the intervention to be delivered by HH staff instead of research staff). We implemented the adapted intervention in two HH agencies to assess feasibility, acceptability, and patient outcomes (i.e., hospice/palliative care election).

FIG. 1.

Process for making adaptations to Casarett et al.'s intervention rooted in Planned Adaptation Model by Lee et al.

Our nine-week pilot test was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Research Triangle Institute.

Setting

We conducted the pilot test at two North Carolina nonprofit HH agencies who had an average daily census of 211 and 270, and average length of stay of 25.5 and 21.5 days.

Participants, recruitment, and enrollment

Each HH agency identified a registered nurse (RN) and clinical manager to participate in the pilot.

Clinical managers were responsible for identifying HH patients who met the eligibility criteria of being “high risk” or “frail,” defined has having triggered an alert for moderate-to-high hospitalization risk (based on Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services methodology) or being a candidate for hospice referral (based on a proprietary algorithm in the HH agencies' data and analytics software program, Strategic Healthcare Programs [SHP]).13

Once an eligible patient was identified, clinical managers alerted the study RNs. During their next HH visit, RNs reviewed the study with patients (or proxies, for the cognitively impaired) and enrolled those who agreed to participate.

Intervention

RNs completed three intervention steps: (1) administered screening questions (Table 1) to eligible patients/proxies during an inperson HH visit, (2) reported screening results to the patient/proxy and asked them to authorize follow-up with their physician regarding hospice or palliative care, if the patient screened positive, and (3) if authorized, initiated appropriate referral per their agency's usual referral processes.

Table 1.

Intervention Hospice Appropriateness Screening Questions

| Question(s) | Response option(s) |

|---|---|

| Domain 1: Symptom needs | |

| Assesses four psychological and seven physical symptoms | |

| Have [you/the patient] been [feeling sad, worrying, feeling irritable, and feeling nervous]? | None, rarely, occasionally, frequently, almost constantly, do not know |

| Has [lack of appetite, lack of energy, pain, drowsiness/confusion, constipation, dyspnea/shortness of breath, nausea] been bothering [you/the patient]? | Not at all, a little bit, somewhat, quite a bit, very much, do not know |

| Domain 2: Service needs | |

| Assesses whether the patient/caregiver could benefit from eight additional services | |

| Would it help to have an [extra nurse to help treat symptoms, extra doctor to help treat symptoms, extra home health aide to help with bathing and eating, extra social worker to arrange finances and insurance, extra social worker or chaplain to provide counseling and emotional support, bereavement counselor to offer support to family if patient died, extra chaplain to provide spiritual support, extra volunteer to spend time with patient/family]? | Yes, no, unsure |

| Domain 3: Care goals | |

| Assesses whether the patient prioritizes maximizing quality of life or extending life | |

| Imagine that [you/your family member] had to make a decision right now about how your doctors should take care of you. If [you/he/she] had to make a decision right now, would [you/he/she] prefer a course of treatment that focuses on extending life as much as possible, even if it means having more pain and discomfort, or would [you/he/she] want a plan of care that focuses on relieving pain and discomfort as much as possible, even if that means not living has long? | Relieving pain/discomfort (palliative care), extending life, do not know |

| Domain 4: Care preferences | |

| Assesses preference for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and mechanical ventilation | |

| Some people make plans about how they want their doctors to take care of them. So now, I would like to talk about how [you/your family member] want [your/your family member's] doctors to take care of [you/him/her]. For example, if [your/patient name] heart stops beating, do you want [your/his/her] doctors to try to restart it? | Yes, no, unsure |

| And if [you/patient name] isn't able to breathe on [your/his/her] own, would you want [your/his/her] doctors to put [you/him/her] on a breathing machine? | |

RNs recorded responses to screening questions on paper; clinical managers uploaded data to a secure server. A positive screen was defined as any patient who had at least one hospice-aligned care need (symptom or service need), care goal, or care preference. Supplementary Data contains the complete intervention protocol, which also served as the paper data collection form.

Data sources and measures

Data sources included (1) paper data collection forms and (2) biweekly process interviews conducted with pilot site staff (i.e., two RNs, two clinical managers, and the HH director for both agencies). The interviews were used to gather input on experience with the intervention and suggestions for improvement. The lead author (M.A.K.) led all 30–45-minute telephone interviews (n = 4), taking detailed notes during each.

Outcomes assessed include feasibility, acceptability, and patient outcomes. The data sources and measures for these outcomes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Measures and Data Sources

| Construct | Measure or definition | Data type and source |

|---|---|---|

| Feasibility | ||

| Patient enrollment rates | Number and percentage of eligible patients who enrolled in the study | Quantitative—paper data collection forms submitted by pilot sites for each patient |

| Fidelity | Missing and error rates for each component of the intervention | Quantitative—paper data collection forms submitted by pilot sites for each patient |

| Acceptability | ||

| Patient attrition rates | Number and percentage of enrolled patients who dropped out of the study (refused to answer all study questions) | Quantitative—paper data collection forms submitted by pilot sites for each patient |

| Experience with intervention | Feedback on value added of the intervention | Qualitative—process interviews |

| Suggestions for improvement: Further refinements to intervention Considerations for scale up |

Feedback on further refinements to the intervention (changes to intervention content or intervention delivery) Feedback considerations for scale up (implementation supports that would be necessary to scale up the intervention within an organization) |

Qualitative—process interviews |

| Patient outcomes | ||

| Screening results | Number and percentage of enrolled patients who screened positive for hospice appropriateness | Quantitative—paper data collection forms submitted by pilot sites for each patient |

| Hospice and palliative care election | Number and percentage of patients who screened positive for hospice appropriateness who elected hospice or palliative care | Quantitative—paper data collection forms submitted by pilot sites for each patient |

Analyses

Quantitative data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Qualitative data from the process interviews were analyzed by lead author (M.A.K.) using template analysis to identify a priori and emergent themes.14

Results

Feasibility

Enrollment rates

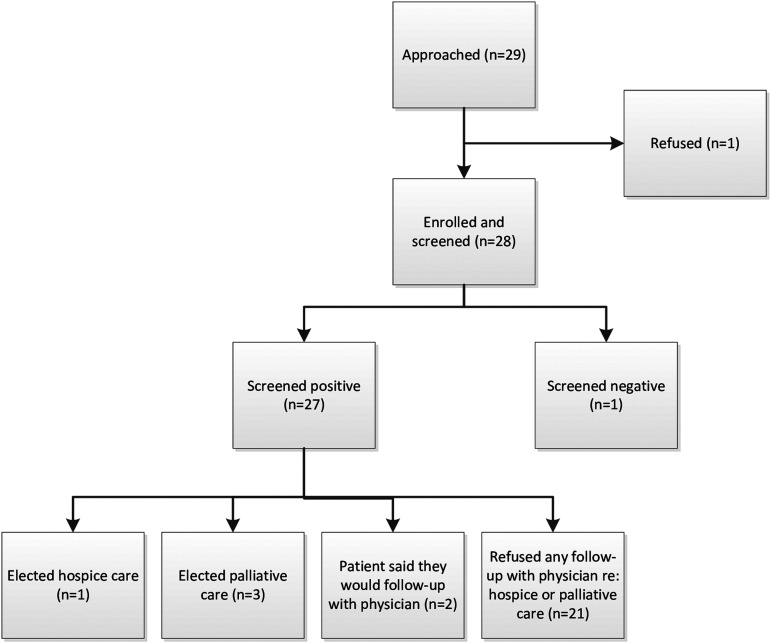

Of 29 eligible patients who were approached for participation, 28 (96.6%) were enrolled and screened (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Patient enrollment and outcome data.

Fidelity

Overall, fidelity to intervention protocol was high. All screening questions were asked of all eligible patients. However, not all patients who screened positive for hospice appropriateness were asked to authorize follow-up with their physician regarding hospice/palliative care. In three instances wherein a patient had only a symptom need, RNs did not broach the subject of hospice/palliative care. In interviews, RNs stated that this decision was made based on their clinical judgment that symptom-need alone was insufficient to deem the patient appropriate for hospice and/or palliative care.

Acceptability

Attrition rates

Patients who enrolled completed all portions of the intervention (i.e., responded to all screening questions) and none withdrew.

Staff experience with intervention

HH staff stated that the intervention facilitated end-of-life care conversations. RNs said that, although they were already having these conversations, the intervention helped improve conversations by structuring the discussion, especially for patients uncomfortable with this topic or for whom the RN did not have an established relationship. The intervention yielded structured information on the patient's care goals, needs, and preferences, which provided a useful framework for difficult conversations (i.e., allowed the RN to repeat back the patient's stated wishes as a segue to hospice/palliative care, such as “You stated you were having problems with pain and you're interested in maximizing comfort. There are care options available that can help you achieve these goals.”).

Suggestions for improvement

Pilot staff suggested that repeating the screening conversation at multiple time points would allow for follow-up and continued conversations about end of life because many patients are not ready to make decisions about hospice/palliative care during the first discussion. Staff also suggested relaxing screening eligibility parameters (where symptom-need only patients would not be considered a positive screen) and allowing flexibility for clinical judgment (in cases wherein a patient is eligible per eligibility criteria but staff do not feel screening is appropriate). In addition, they suggested reframing the introduction to the screening to initiate the conversation in a less threatening way (e.g., prefacing with “this is something we do as part of routine care for all our patients” vs. an introduction that implies the patient was selected based on clinical or functional criteria).

Patient outcomes

Of the 28 screened patients, 27 (96.4%) screened positive for potential hospice appropriateness. Of those 27 patients, 3 entered palliative care and 1 elected hospice (14.8% elected hospice or palliative care); 2 other patients who screened positive (7.4%) intended to follow-up with their physician about these options (Fig. 2).

Discussion

This pilot study evaluating the adapted intervention found favorable results for feasibility, acceptability, and election of hospice/palliative care. Pilot sites implemented the intervention with high fidelity and reported low burden in required workflow changes. Fourteen percent of patients who screened positive enrolled in hospice or palliative care—slightly lower than the 20% observed in the Casarett trial in which the research team, rather than clinical staff, delivered the intervention.10

High patient enrollment (96.6%) and screening question completion rates (100%) suggest that patients are willing to discuss their care needs, goals, and preferences. The relatively high number of patients that screened positive for hospice appropriateness but did not elect hospice/palliative care during the study period (23 of 27 patients) suggests that considerations besides appropriateness factor into the decision to elect hospice/palliative care. Based on feedback from study RNs, although patients may be appropriate, they simply are not ready to make a decision during the first discussion; readiness may be an important additional construct that is not assessed by this intervention. Repeating the screening at multiple time points, as suggested by RNs, may facilitate ongoing conversation as patients become ready. In addition, further research investigating the concept of readiness may be warranted (e.g., time to readiness once identified as appropriate).

This research had several limitations. First, the small sample size and number of nurses delivering the intervention limit generalizability. Second, pilot sites had strong leadership commitment, organizational goals aligned with intervention goals, and favorable attitudes toward the intervention, which may not be typical of all HH agencies. The sites also had inhouse palliative care services to which they could refer patients, which is not true for all HH agencies. Finally, coding of qualitative data was completed by one coder, who is also the lead author of this article.

Conclusion

We adapted an intervention to improve timeliness of hospice referrals for HH patients, broadening its potential reach to appropriate patients. Findings indicate that the adapted intervention was feasible and acceptable in the target setting. Further studies are needed to explore additional adaptations and assess effectiveness, long-term impact, and sustainability.

Supplementary Material

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Lee IC, et al. : Does hospice improve quality of care for persons dying from dementia?. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:1531–1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller SC, Mor V, Wu N, et al. : Does receipt of hospice care in nursing homes improve the management of pain at the end of life?. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:507–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. Alexandria, VA: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, April 2018. https://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2017_Facts_Figures.pdf (Last accessed February1, 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 4. Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ: Impact of individual and market factors on the timing of initiation of hospice terminal care. Med Care 2000;38:528–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rickerson E, Harrold J, Kapo J, et al. : Timing of hospice referral and families' perceptions of services: Are earlier hospice referrals better? J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:819–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Friedman BT, Harwood MK, Shields M: Barriers and enablers to hospice referrals: An expert overview. J Palliat Med 2002;5:73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cherlin E, Fried T, Prigerson HG, et al. : Communication between physicians and family caregivers about care at the end of life: When do discussions occur and what is said?. J Palliat Med 2005;8:1176–1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jenkins T, Chapman K, Ritchie C, et al. : Barriers to hospice care in alabama: Provider-based perceptions. Am J Palliat Care 2011;28:153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, et al. : Why don't patients enroll in hospice? Can we do anything about it?. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:1009–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stanley JM: What the people would want if they knew more about it: A case for the social marketing of hospice care. Hastings Cent Rep 2003:Suppl:S22–S23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Casarett D, Karlawish J, Morales K, et al. : Improving the use of hospice services in nursing homes: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;294:211–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee SJ, Altschul I, Carol T: Mowbray. Using planned adaptation to implement evidence-based programs with new populations. Am J Community Psychol 2008;41:290–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clayton Zeb: Strategic Healthcare Programs. SHP for Agencies: 101 Introduction to SHP. https://secure.shpdata.com/download/shpuniversity/training/agencies/101_Course_Handouts.pdf (Last accessed February1, 2019)

- 14. Spencer L, Ritchie R: Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research.In: Analyzing Qualitative Data. Routledge, London, 2002, pp. 187–208 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.