Abstract

BACKGROUND

Critically ill patients with cirrhosis, particularly those with acute decompensation, have higher mortality rates in the intensive care unit (ICU) than patients without chronic liver disease. Prognostication of short-term mortality is important in order to identify patients at highest risk of death. None of the currently available prognostic models have been widely accepted for use in cirrhotic patients in the ICU, perhaps due to complexity of calculation, or lack of universal variables readily available for these patients. We believe a survival model meeting these requirements can be developed, to guide therapeutic decision-making and contribute to cost-effective healthcare resource utilization.

AIM

To identify markers that best identify likelihood of survival and to determine the performance of existing survival models.

METHODS

Consecutive cirrhotic patients admitted to a United States quaternary care center ICU between 2008-2014 were included and comprised the training cohort. Demographic data and clinical laboratory test collected on admission to ICU were analyzed. Area under the curve receiver operator characteristics (AUROC) analysis was performed to assess the value of various scores in predicting in-hospital mortality. A new predictive model, the LIV-4 score, was developed using logistic regression analysis and validated in a cohort of patients admitted to the same institution between 2015-2017.

RESULTS

Of 436 patients, 119 (27.3%) died in the hospital. In multivariate analysis, a combination of the natural logarithm of the bilirubin, prothrombin time, white blood cell count, and mean arterial pressure was found to most accurately predict in-hospital mortality. Derived from the regression coefficients of the independent variables, a novel model to predict inpatient mortality was developed (the LIV-4 score) and performed with an AUROC of 0.86, compared to the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, Chronic Liver Failure-Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, and Royal Free Hospital Score, which performed with AUROCs of 0.81, 0.80, and 0.77, respectively. Patients in the internal validation cohort were substantially sicker, as evidenced by higher Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation III, SOFA and LIV-4 scores. Despite these differences, the LIV-4 score remained significantly higher in subjects who expired during the hospital stay and exhibited good prognostic values in the validation cohort with an AUROC of 0.80.

CONCLUSION

LIV-4, a validated model for predicting mortality in cirrhotic patients on admission to the ICU, performs better than alternative liver and ICU-specific survival scores.

Keywords: Risk stratification, Resource allocation, Intensive care unit, Acute-on-chronic liver failure, Modeling, Mortality

Core tip: Critically ill patients with cirrhosis have higher mortality rates in the intensive care unit (ICU) than patients without chronic liver disease. None of the currently available prognostic models have been widely accepted for use in cirrhotic patients in the ICU, perhaps due to complexity of calculation. We believe survival modeling can guide therapeutic decision-making and contribute to cost-effective healthcare resource utilization. We describe the development of a novel model to predict in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with cirrhosis. Our validated model for predicting mortality on admission to the ICU performs better than previously published liver and ICU-specific scores.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with cirrhosis, particularly those with acute decompensation necessitating intensive care unit (ICU) admission, are at elevated risk for short-term mortality[1-3]. Acute-on-chronic liver failure, as defined by sequential organ failure in patients with cirrhosis, portends a poorer prognosis, with 28-day mortality approaching 80% in patients with 3 or more organ failures[1,4-7]. The most recent data from the nationwide inpatient sample in the United States estimates that more than 26000 patients with cirrhosis are admitted to ICUs annually, of which less than half (about 47%) survive hospitalization[7,8]. Critical care for patients with cirrhosis is estimated to cost upwards of United States $3 billion annually, with each admission totaling on average United States $116200[8]. Survival analysis tools aid in the early identification of critically ill patients, which, when applied as part of therapeutic decision-making, can help guide goals of critical care discussions with patients and their families, and may contribute to cost-effective healthcare resource utilization[9].

To this end, the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) methodology[10] and the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (APS)[11] are widely applied to estimate the risk of inpatient mortality based on values collected from within the first 24 hours of critical care admission. Similarly, the Sequential (or Sepsis-Related) Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) is commonly used to describe, compare, and track a patient's clinical course in the ICU[9]. On the other hand, liver-specific scores, such as the Child-Pugh Score, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), MELD-Sodium (MELD-Na) and Chronic Liver Failure-SOFA (CLIF-SOFA) are broadly applied in patients with liver disease to predict 90-day mortality, allocate donor organs for liver transplantation, and to define hepatic decompensation as well as acute-on-chronic liver failure[1,12-16]. Critical care scoring systems that include the assessment of organ dysfunction have generally performed as well, or better, in patients with cirrhosis than these liver-specific models for short-term mortality[1,17-28]. However, none of these prognostic models have been widely accepted for use in clinical practice, perhaps due to complexity of calculation, or lack of universal variables readily available for cirrhotic patients in the ICU. We aimed to identify markers that best identify likelihood of transplant-free survival in critically ill patients with cirrhosis and to determine the performance of existing survival models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study aims

The aims of this study are to: (1) Identify clinical and laboratory markers universally available at the time of ICU admission that best identify the likelihood of survival; and (2) To compare this model to existing survival models.

Study design

Patients over the age of 18 with a diagnosis of cirrhosis admitted between 2008-2014 to an ICU at a major quaternary referral and liver transplantation center in the United States comprised the training cohort. Patients from the APACHE IVb database (a prospective database of consecutive patients admitted to the ICU) were identified retrospectively by searching the database for the APACHE chronic health items (1) hepatic failure and (2) cirrhosis. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was subsequently confirmed either (1) radiographically, based on imaging evidence of cirrhosis or portal hypertension; (2) histologically by liver biopsy, if performed, and/or (3) by evidence of hepatic decompensation, including hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, or ascites. Patients with acute liver failure, history of liver transplantation, or who underwent liver transplantation during the contemporaneous hospital admission were excluded from the analysis.

Patient population

Demographic patient data consisting of age, gender, co-morbidities, etiology of chronic liver disease, and vital signs on admission to ICU were recorded from the electronic medical record. Clinical laboratory tests collected on admission to ICU included platelet count, prothrombin time (PT), International normalized ratio, lactate, arterial blood gas, pH, partial arterial pressure of carbon dioxide and oxygen, inspired oxygen concentration (FiO2), oxygen/FiO2, alveolar-arterial partial pressure oxygen gradient (A-a gradient), hematocrit, white blood cell count (WBC), potassium, blood urea nitrogen, albumin, sodium (Na), creatinine, bilirubin, bicarbonate, and glucose. Additional clinical parameters, including 24-hour urine output, need for mechanical ventilation, need for dialysis, variceal hemorrhage, Glascow coma scale, vasopressor dose, and degree of ascites and encephalopathy were recorded. This information was used to grade the severity of liver disease and prognosticate ICU mortality based on the calculation of previously validated liver-specific and ICU prognostic scores, including the MELD, MELD-Na, Child-Pugh, SOFA, CLIF-SOFA, Royal Free Hospital (RFH), APS and APACHE III scores. Subjects were followed from admission to hospital discharge or death.

The internal validation cohort was comprised of prospectively enrolled patients over the age of 18 with a diagnosis of cirrhosis admitted to the same institution as the training cohort between 2015-2017 and were subject to identical exclusion criteria. All patients that met the inclusion criteria were included in the analysis; no formal sample size calculations were done. The Institutional Review Board of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation reviewed and approved this study. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Statistical analysis

A univariate and then multivariate analysis was performed to assess factors associated with in-hospital mortality. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (25th, 75th percentiles) or n (%). Analysis of variance or the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for continuous or ordinal variables and Pearson’s chi-square tests were used for categorical factors. In addition, Spearman correlations coefficients were used to assess correlation between length of stay and the different scores.

Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) analysis was performed to assess the value of various scores in predicting in-hospital mortality; areas under the ROC curves (AUROC) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals are presented.

A predictive model was developed using logistic regression analysis. An automated stepwise variable selection method performed on 1000 bootstrap samples was used to choose the final model. All variables known at time of ICU admission were considered for inclusion. Variables with inclusion rates of at least 50% were further assessed and the most parsimonious model with highest AUROC is reported. Variable transformations were assessed to account for any possible non-linearity. Observations with missing values were not included when building models.

After choosing the final model, the method described by Harrell[29] was used to compute the validation metric with over-fitting bias correction through bootstrap resampling. A thousand bootstrap samples (B = 1000) were drawn from the original data set and a new model with the same model settings was built on each bootstrap resample. Prediction on patients that were not chosen in the resample was calculated. An optimism factor was calculated over the 1000 new models and the bias-corrected validation metric was obtained by subtracting this optimism value from the AUROC directly measured from the original model. In addition, the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit χ2 test and calibration plots were used to assess calibration of the models. DeLong’s method was used to compare predictive ability of LIV-4 to that of the various scores by comparing AUROCs[30]. A univariable analysis was performed to assess differences between the training and validation cohorts. SAS (version 9.4, The SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States) was used for all analyses and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical review was performed by a biomedical statistician.

RESULTS

Training cohort

Patient characteristics: Training Cohort. In total, 436 patients cirrhotic patients, aged 57 ± 10.6 years, 65.4% males, mostly with alcohol-related liver disease -(45.2%), Hepatitis C Virus -(33.7%) and Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis -(22%) related cirrhosis were included in the training cohort (Table 1). The majority of patients presented with severely decompensated liver disease, evidenced by the presence of moderate/severe encephalopathy (47.5%), moderate/severe ascites (44.3%), or variceal bleeding (25.7%) on admission, with median MELD score of 23.3 and Child-Pugh Score of 10.2 (C). 119 patients (27.3%) died in the hospital. The median ICU length of stay was 2.6 (25th, 75th percentiles: 1.4, 5.2) d and the median hospital length of stay was 8.7 (4.7, 16.8) d.

Table 1.

Training cohort: Patient characteristics and univariate analysis of factors associated with In-hospital mortality

| Factor |

Total (n = 436) |

Discharged alive (n = 317) |

In-hospital death (n = 119) |

P value | |||

| n | Summary | n | Summary | n | Summary | ||

| Age (yr) | 436 | 57.0 ± 10.6 | 317 | 57.5 ± 10.3 | 119 | 55.5 ± 11.3 | < 0.0811 |

| Gender | 436 | 317 | 119 | < 0.623 | |||

| Female | 151 (34.6) | 112 (35.3) | 39 (32.8) | ||||

| Male | 285 (65.4) | 205 (64.7) | 80 (67.2) | ||||

| Ethnicity | 420 | 308 | 112 | < 0.413 | |||

| White/Caucasian | 340 (81.0) | 254 (82.5) | 86 (76.8) | ||||

| Black/African/Haitian | 60 (14.3) | 41 (13.3) | 19 (17.0) | ||||

| Other | 20 (4.8) | 13 (4.2) | 7 (6.3) | ||||

| Any previous ICU stay during same admission | 436 | 13 (3.0) | 317 | 6 (1.9) | 119 | 7 (5.9) | < 0.0293 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Diabetes | 436 | 129 (29.6) | 317 | 100 (31.5) | 119 | 29 (24.4) | < 0.143 |

| COPD | 436 | 61 (14.0) | 317 | 49 (15.5) | 119 | 12 (10.1) | < 0.153 |

| Severe COPD | 436 | 12 (2.8) | 317 | 10 (3.2) | 119 | 2 (1.7) | < 0.403 |

| Solid tumor with metastasis | 436 | 3 (0.69) | 317 | 1 (0.32) | 119 | 2 (1.7) | < 0.182 |

| Immune suppression | 436 | 21 (4.8) | 317 | 16 (5.0) | 119 | 5 (4.2) | < 0.713 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 436 | 170 (39.0) | 317 | 111 (35.0) | 119 | 59 (49.6) | < 0.0053 |

| Dialysis > 2 times in 7 d | 436 | 35 (8.0) | 317 | 20 (6.3) | 119 | 15 (12.6) | < 0.0313 |

| Liver disease etiology | |||||||

| AIAT | 436 | 9 (2.1) | 317 | 8 (2.5) | 119 | 1 (0.84) | < 0.273 |

| AIH | 436 | 17 (3.9) | 317 | 11 (3.5) | 119 | 6 (5.0) | < 0.453 |

| ALD | 436 | 197 (45.2) | 317 | 138 (43.5) | 119 | 59 (49.6) | < 0.263 |

| Cryptogenic | 436 | 25 (5.7) | 317 | 21 (6.6) | 119 | 4 (3.4) | < 0.193 |

| HCV | 436 | 147 (33.7) | 317 | 102 (32.2) | 119 | 45 (37.8) | < 0.273 |

| HBV | 436 | 9 (2.1) | 317 | 5 (1.6) | 119 | 4 (3.4) | < 0.243 |

| NASH | 436 | 96 (22.0) | 317 | 75 (23.7) | 119 | 21 (17.6) | < 0.183 |

| PBC | 436 | 6 (1.4) | 317 | 5 (1.6) | 119 | 1 (0.84) | < 0.994 |

| PSC | 436 | 2 (0.46) | 317 | 2 (0.63) | 119 | 0 (0.0) | < 0.994 |

| 24-hour urine output (cc) | 400 | 1005.2 (454.8, 1589.8) | 295 | 1090.0 (633.3, 1726.6) | 105 | 563.8 (105.6, 1210.9) | < 0.0012 |

| Variceal bleed | 436 | 112 (25.7) | 317 | 86 (27.1) | 119 | 26 (21.8) | < 0.263 |

| Vasopressors on day of admission | 436 | 317 | 119 | < 0.0012 | |||

| 0 | 208 (47.7) | 170 (53.6) | 38 (31.9) | ||||

| 1 | 175 (40.1) | 126 (39.7) | 49 (41.2) | ||||

| ≥ 2 | 53 (12.12) | 21 (6.63) | 32 (26.9) | ||||

| Encephalopathy | 436 | 317 | 119 | < 0.432 | |||

| None | 106 (24.3) | 81 (25.6) | 25 (21.0) | ||||

| Mild | 123 (28.2) | 88 (27.8) | 35 (29.4) | ||||

| Moderate/severe | 207 (47.5) | 148 (46.7) | 59 (49.6) | ||||

| Ascites | 436 | 317 | 119 | < 0.0852 | |||

| None | 114 (26.1) | 86 (27.1) | 28 (23.5) | ||||

| Mild | 129 (29.6) | 100 (31.5) | 29 (24.4) | ||||

| Moderate/severe | 193 (44.3) | 131 (41.3) | 62 (52.1) | ||||

| Labs and vitals | |||||||

| Platelets (k/μL) | 436 | 81.0 (56.5, 117.5) | 317 | 83.0 (60.0, 117.0) | 119 | 73.0 (49.0, 119.0) | < 0.212 |

| Prothrombin time (sec) | 436 | 16.8 (14.2, 20.7) | 317 | 15.6 (13.7, 18.0) | 119 | 21.4 (18.3, 27.8) | < 0.0012 |

| INR | 436 | 1.5 (1.3, 1.9) | 317 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | 119 | 2.0 (1.7, 2.6) | < 0.0012 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 341 | 2.3 (1.6, 3.4) | 230 | 2.1 (1.4, 2.7) | 111 | 3.0 (2.1, 5.4) | < 0.0012 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 436 | 65.0 (56.0, 106.0) | 317 | 68.0 (60.0, 109.0) | 119 | 58.0 (50.0, 68.0) | < 0.0012 |

| ABG-pH | 263 | 7.4 ± 0.10 | 170 | 7.4 ± 0.08 | 93 | 7.3 ± 0.12 | < 0.0011 |

| ABG-PaCO2 (mmHg) | 263 | 31.0 (27.0, 38.0) | 170 | 31.0 (26.0, 37.0) | 93 | 33.0 (27.0, 40.0) | < 0.0982 |

| ABG-PaO2 (mmHg) | 263 | 104.0 (80.0, 139.0) | 170 | 113.0 (85.0, 147.0) | 93 | 94.0 (76.0, 132.0) | < 0.0192 |

| ABG-FiO2 (%) | 263 | 40.0 (27.0, 55.0) | 170 | 40.0 (25.0, 50.0) | 93 | 44.0 (30.0, 70.0) | < 0.0082 |

| PaO2/FIO2 ratio | 263 | 309.5 (195.0, 390.5) | 170 | 337.5 (226.0, 426.7) | 93 | 252.5 (143.0, 347.4) | < 0.0012 |

| PAO2 (mmHg) | 263 | 240.2 (151.0, 346.2) | 171 | 231.5 (143.3, 324.0) | 93 | 264.0 (168.4, 471.6) | < 0.0082 |

| A-a gradient (mmHg) | 263 | 119.8 (47.4, 233.9) | 171 | 100.2 (38.6, 204.3) | 93 | 166.7 (59.5, 319.6) | < 0.0012 |

| Temperature (°C) | 436 | 36.5 (36.2, 36.8) | 317 | 36.5 (36.3, 36.8) | 119 | 36.3 (35.4, 36.6) | < 0.0012 |

| GCS | 436 | 13.0 (8.0,14.0) | 317 | 13.0(9.0,15.0) | 119 | 11.0 (7.0, 14.0) | < 0.0012 |

| Respiratory rate (rpm) | 436 | 33.0 (26.0, 40.0) | 317 | 33.0 (25.0, 39.0) | 119 | 36.0 (27.0, 43.0) | < 0.0522 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 436 | 92.8 ± 28.1 | 317 | 91.8 ± 25.7 | 119 | 95.5 ± 33.6 | < 0.211 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 436 | 26.6 ± 5.9 | 317 | 27.1 ± 5.7 | 119 | 25.3 ± 6.2 | < 0.0051 |

| WBC (k/μL) | 436 | 7.5 (5.0, 11.4) | 317 | 6.6 (4.6, 9.8) | 119 | 10.7 (6.6, 17.7) | < 0.0012 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 436 | 4.0 (3.6, 4.8) | 317 | 3.9 (3.5, 4.6) | 119 | 4.4 (3.8, 5.1) | < 0.0012 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 436 | 35.0 (21.0, 55.5) | 317 | 32.0 (20.0, 51.0) | 119 | 46.0 (28.0, 66.0) | < 0.0012 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 436 | 2.7 (2.2, 3.1) | 317 | 2.7 (2.3, 3.1) | 119 | 2.7 (2.2, 3.3) | < 0.572 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 436 | 136.6 ± 6.8 | 317 | 136.6 ± 6.6 | 119 | 136.4 ± 7.3 | < 0.811 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 436 | 1.6 (0.89, 2.8) | 317 | 1.4 (0.80, 2.4) | 119 | 2.2 (1.4, 3.5) | < 0.0012 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 435 | 4.2 (2.0, 10.4) | 316 | 3.3 (1.7, 6.2) | 119 | 11.7 (5.6, 25.9) | < 0.0012 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 424 | 19.3 ± 5.4 | 310 | 19.9 ± 4.9 | 114 | 17.7 ± 6.3 | < 0.0011 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 430 | 152.6 ± 90.3 | 314 | 153.9 ± 94.0 | 116 | 149.1 ± 79.8 | < 0.631 |

| Scores | |||||||

| MELD score | 435 | 23.2 ± 9.8 | 316 | 20.3 ± 8.3 | 119 | 31.1 ± 8.9 | < 0.0011 |

| MELD-Na score | 435 | 24.8 ± 9.2 | 316 | 22.1 ± 8.1 | 119 | 32.0 ± 8.1 | < 0.0011 |

| Child-Pugh score | 435 | 10.8 ± 2.1 | 316 | 10.3 ± 2.1 | 119 | 11.9 ± 1.8 | < 0.0011 |

| SOFA score | 263 | 10.2 ± 3.5 | 170 | 9.0 ± 2.9 | 93 | 12.4 ± 3.4 | < 0.0011 |

| CLIF-SOFA score | 262 | 11.2 ± 3.5 | 169 | 9.9 ± 3.0 | 93 | 13.5 ± 3.2 | < 0.0011 |

| RFH score | 259 | 0.05 (-0.77, 1.1) | 167 | -0.30 (-0.99, 0.59) | 92 | 0.96 (0.08, 2.1) | < 0.0012 |

| APS | 435 | 65.6 ± 28.4 | 317 | 58.0 ± 22.1 | 118 | 86.2 ± 32.8 | < 0.0011 |

| APACHE III score | 435 | 85.1 ± 28.3 | 317 | 77.7 ± 23.1 | 118 | 105.0 ± 31.5 | < 0.0011 |

Values presented as Mean ± SD, Median (P25, P75) or n (column %). P values:

ANOVA.

Kruskal-Wallis test.

Pearson’s χ2 test.

Fisher’s Exact test. ICU: Intensive care unit; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; A1AT: Alpha 1 anti-trypsin deficiency; AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; ALD: Alcoholic liver disease; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; PBC: Primary biliary cholangitis; PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis; INR: International normalized ratio; MAP: Mean arterial pressure; ABG: Arterial blood gas; PaCO2: Partial arterial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2: Oxygen; FiO2: Inspired oxygen concentration; A-a gradient: Alveolar arterial partial pressure oxygen gradient; FiO2/PaO2: Oxygenation index; GCS: Glascow coma scale; rpm: Respirations per minute; bpm: Beats per minute; WBC: White blood cell count; BUN: Blood urea nitrogen; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease; Na: Sodium; CPS: Child-Pugh score; SOFA: Sequential (or sepsis-related) organ failure assessment; CLIF-SOFA: Chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment; RFH: Royal free hospital; APS: Acute physiology score; APACHE: Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation.

Factors associated with in-hospital mortality

Table 1 summarizes univariable comparisons of subjects who died and those who were discharged alive. There was no significant difference in patient age, gender, ethnicity, etiology of liver disease or co-morbidities between survivors and non-survivors. Survivors had lower MELD (20.3 vs 31.1) and Child-Pugh (10.3 vs 11.9) scores. Variceal hemorrhage (P = 0.26), presence/grade of hepatic encephalopathy (P = 0.43), and presence/degree of ascites (P = 0.85) were not predictive of in-hospital mortality.

Patients who died in the hospital were more likely to require mechanical ventilation (49.6% vs 35%, P = 0.005) and dialysis (12.6% vs 6.3%, P = 0.031) on admission to the ICU than patients who survived. Patients who did not survive hospitalization had significantly lower mean arterial pressure (MAP), temperature and Glasgow coma scale (P < 0.001). Additionally, non-survivors were more likely to have lower hematocrit and bicarbonate, as well as higher WBC, A-a gradient, lactate, PT/International normalized ratio, potassium, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and bilirubin (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in serum sodium or albumin levels between survivors and non-survivors (P = 0.81 and 0.57, respectively).

In multivariate analysis, a combination of the natural logarithm (ln) of the bilirubin, PT, WBC, and MAP was found to most accurately predict in-hospital mortality. Based on the regression coefficients of the independent variables (Table 2), a novel model to predict inpatient mortality was established. The final proposed model was defined as: z = 1.19330 + [0.6137 × ln (bilirubin)] – (47.203/PT) + (0.0715 × WBC) – (0.0198 × MAP). The z value is subsequently converted into a risk score to calculate probability of mortality utilizing the formula: LIV-4 = Probability of death (%) = [ez/(1 + ez)] × 100. Percentage values range from 0 to 100.

Table 2.

Training cohort: Factors associated with in-hospital mortality: multivariate logistic regression with variable transformations

| Factor | Estimate (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Ln (Bilirubin) | 0.61 (0.34, 0.89) | 1.8 (1.4, 2.4) | < 0.001 |

| 1/PT | -47.2 (-67.3, -27.1) | 0.09 (0.03, 0.26)1 | < 0.001 |

| WBC | 0.07 (0.03, 0.11) | 1.07 (1.03, 1.1) | < 0.001 |

| MAP | -0.02 (-0.03, -0.01) | 0.91 (0.86, 0.96)2 | < 0.001 |

OR corresponds to 0.05 increment in 1/PT.

OR corresponds to 5-unit increment in MAP. Ln: Natural logarithm; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; PT: Prothrombin time; WBC: White blood cell count; MAP: Mean arterial pressure.

The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit X2 test was 5.4 (P = 0.72) and the AUROC for this model was 0.86 (95%CI: 0.82-0.90). Using bootstrap resampling, internal validation of the model was undertaken and produced an AUROC of 0.85. Based on Youden's index[31] and using a cutoff of 26.5, the new score performed with a sensitivity of 81%, specificity of 76%, Positive Predictive Value of 58%, and Negative Predictive Value of 92%. Alternatively, a cutoff of 45.8 yields a sensitivity of 61% and specificity of 90%.

Comparison of prognostic models

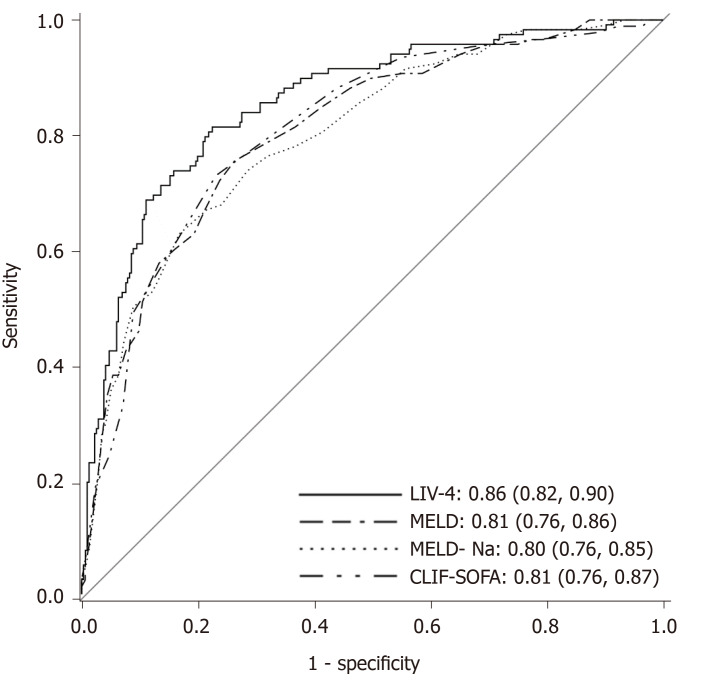

Several scores demonstrated excellent accuracy for prediction of in-hospital mortality. The CLIF-SOFA and MELD scores, both liver-specific models, performed the best in the cohort with AUROCs of 0.81. The RFH score performed with an AUROC of 0.77. By comparison, ICU-specific scores, including the SOFA, APS and APACHE III performed with AUROCs of 0.79, 0.76, and 0.76, respectively. The liver intensive care unit variable-4 score (the LIV-4 score) performed higher than all other models, with an AUROC of 0.86. Figure 1 displays AUROCs of the top-performing scores. DeLong et al[30]s method was employed to compare the predictive ability of the new model to that of the other scores. The LIV-4 score performed significantly better than the MELD, MELD-Na, Child-Pugh Score, RFH and APACHE III scores (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Training cohort: Predictive scores for in-hospital mortality in cirrhotic patients. LIV-4: LIV-4 score; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease; MELD-Na: Model for end-stage liver disease-Sodium; CLIF-SOFA: Chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment.

Table 3.

Training cohort: Predictive abilities of critical care and liver-specific scores compared to the LIV-4 score

| Score compared to LIV-4 | P value |

| MELD | 0.009 |

| MELD-Na | 0.002 |

| Child-Pugh Score | < 0.001 |

| SOFA | 0.061 |

| CLIF-SOFA | 0.091 |

| RFH | 0.04 |

| APS | 0.001 |

| APACHE III | 0.002 |

MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease; Na: Sodium; SOFA: Sequential (or Sepsis-Related) organ failure assessment; CLIF-SOFA: Chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment; RFH: Royal free hospital; APS: Simplified acute physiology score; APACHE: Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation.

Validation cohort

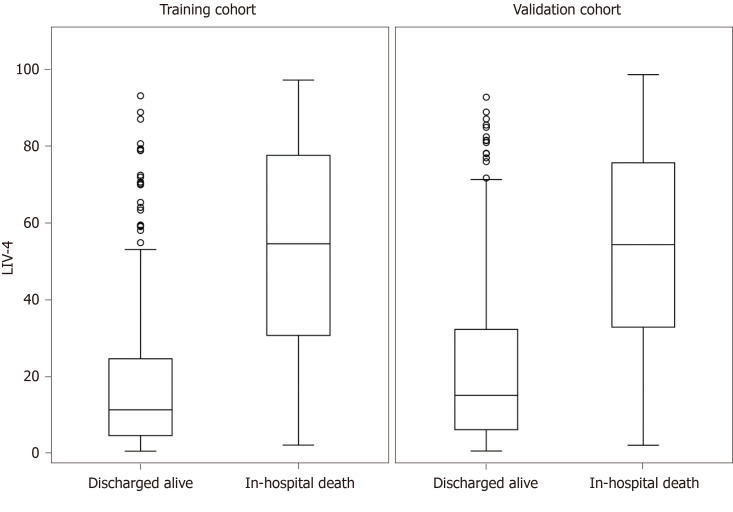

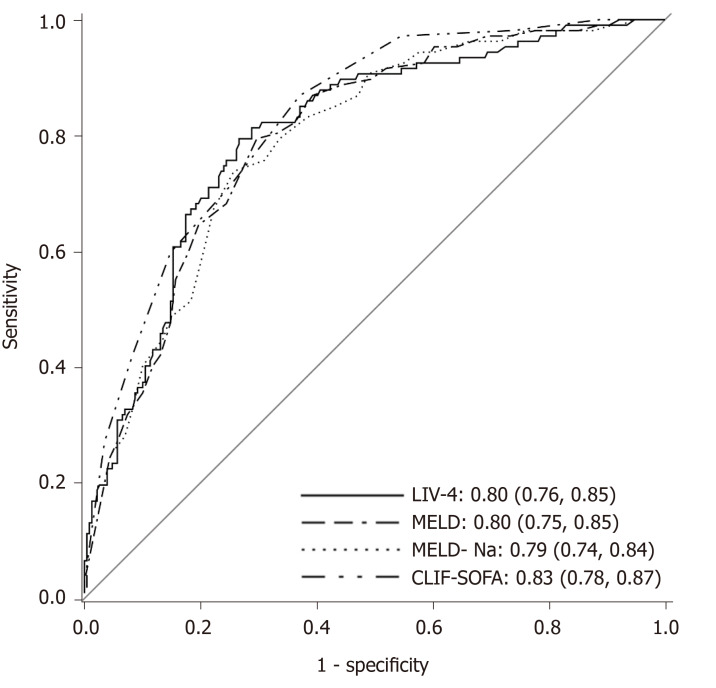

Table 4 presents a comparison of the training and validation cohort characteristics. A total of 336 cirrhotic patients were admitted between 2015-2017, of whom 107 (31.8%) died. Patients in the internal validation cohort were substantially sicker, as evidenced by higher MELD, MELD-Na, APACHE III, SOFA and LIV-4 scores. Despite differences between the cohorts, the LIV-4 score remained significantly higher in subjects who expired during the hospital stay (Figure 2) and exhibited good prognostic values in the validation cohort with an AUROC of 0.80 (Figure 3). There was no statistically significant difference between the LIV-4 score's AUROC from the training cohort and the validation cohort (P = 0.11). In the validation cohort, the SOFA score performed with an AUROC of 0.78, the APACHE III with an AUROC of 0.74, the MELD score with an AUROC of 0.80, the MELD-Na with an AUROC of 0.79, the CLIF-SOFA with an AUROC of 0.83, and the RFH with an AUROC of 0.64. The LIV-4 model performed with a significantly higher AUROC than the RFH [AUROC: 0.64 (0.56, 0.72)], and was non-inferior to other ICU- and liver-specific scores (Table 5). Using a cutoff of 26.5, LIV-4 continued to perform with a high negative predictive value of 89.1 (84.6, 93.6) (Table 6).

Table 4.

Validation cohort characteristics

| Factor |

Training cohort (n = 436) |

Validation cohort A (n = 336) |

P value | ||

| n | Statistics | n | Statistics | ||

| Gender | 436 | 336 | < 0.0302 | ||

| Female | 151 (34.6) | 142 (42.3) | |||

| Male | 285 (65.4) | 194 (57.7) | |||

| Serum bilirubin | 435 | 4.2 (2.0, 10.4) | 336 | 5.0 (2.0, 13.5) | < 0.261 |

| PT | 436 | 16.8 (14.2, 20.7) | 336 | 18.0 (14.8, 23.5) | < 0.0031 |

| WBC | 436 | 7.5 (5.0, 11.4) | 336 | 8.3 (5.0, 14.0) | < 0.0401 |

| MAP | 436 | 65.0 (56.0, 106.0) | 336 | 64.0 (56.0, 75.0) | < 0.261 |

| Non-liver specific scores | |||||

| APACHE III | 435 | 83.0 (65.0, 102.0) | 333 | 88.0 (70.0, 109.0) | < 0.0061 |

| SOFA | 263 | 10.0 (8.0, 12.0) | 186 | 11.0 (8.0, 14.0) | < 0.0031 |

| Liver specific scores | |||||

| MELD | 435 | 22.0 (16.0, 30.0) | 336 | 25.0 (17.0, 33.0) | < 0.0041 |

| MELD-Na | 435 | 24.0 (18.0, 31.0) | 336 | 27.0 (20.0, 34.0) | < 0.0061 |

| CLIF-SOFA | 262 | 11.0 (9.0, 13.0) | 336 | 11.0 (9.0, 13.0) | < 0.531 |

| RFH | 259 | 0.05 (-0.77, 1.1) | 184 | 0.83 (-0.18, 2.1) | < 0.0011 |

| LIV-4 | 435 | 16.8 (5.7, 43.6) | 336 | 23.0 (7.1, 57.7) | < 0.0071 |

| Admission outcomes | |||||

| ICU LOS (d) | 436 | 2.6 (1.4, 5.2) | 336 | 3.7 (2.0, 7.6) | < 0.0011 |

| Hospital LOS (d) | 436 | 8.7 (4.7, 16.8) | 336 | 11.7 (5.7, 22.0) | < 0.0021 |

| Hospital discharge status | 436 | 336 | < 0.172 | ||

| Discharged alive | 317 (72.7) | 229 (68.2) | |||

| In-hospital death | 119 (27.3) | 107 (31.8) | |||

Kruskal-Wallis test.

Pearson’s χ2 test. PT: Prothrombin time; WBC: White blood cell count; MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure; APACHE: Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; SOFA: Sequential (or Sepsis-related) organ failure assessment; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease; Na: Sodium; CLIF-SOFA: Chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment; RFH: Royal Free Hospital; LOS: Length of stay.

Figure 2.

LIV-4 score is higher in subjects who expired during the hospital admission. The box-and-whisker plot is represented by the lower boundary of the box indicating the 25th percentile, the line within the box indicating the median value, the upper boundary of the box indicating the 75th percentile. The whiskers extend to the most extreme data point, which is no more than 1.5 times the interquartile range from the box, and the circles are outliers (values > 1.5 interquartile range).

Figure 3.

Validation cohort: Predictive scores for in-hospital mortality in cirrhotic patients. LIV-4: LIV-4 score; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease; MELD-Na: Model for end-stage liver disease-Sodium; CLIF-SOFA: Chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment.

Table 5.

Validation cohort: Comparison of the various scores and LIV-4

| Score comparison | Validation cohort P value |

| MELD vs LIV-4 | < 0.75 |

| MELD-Na vs LIV-4 | < 0.47 |

| SOFA vs LIV-4 | < 0.94 |

| CLIF-SOFA vs LIV-4 | < 0.27 |

| RFH vs LIV-4 | < 0.001 |

| APACHE III vs LIV-4 | < 0.074 |

Areas under the ROC curves were compared using De-Long’s method. MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease; Na: Sodium; SOFA: Sequential (or Sepsis-related) organ failure assessment; CLIF-SOFA: Chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment; RFH: Royal Free Hospital; APACHE: Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; ROC: Receiver operator characteristics.

Table 6.

Validity measures for LIV-4

| Cohort | Measure | LIV-4 ≥ 26.5 | LIV-4 ≥ 45.8 |

| Validation Cohort | Sensitivity | 81.3 (73.9, 88.7) | 61.7 (52.5, 70.9) |

| Specificity | 71.2 (65.3, 77.0) | 83.4 (78.6, 88.2) | |

| PPV | 56.9 (49.0, 64.7) | 63.5 (54.2, 72.7) | |

| NPV | 89.1 (84.6, 93.6) | 82.3 (77.4, 87.2) |

Values presented as estimate (95%CI). PPV: Positive predictive value; NPV: Negative predictive value; CI: Confidence Interval.

DISCUSSION

Our new model, the LIV-4 score, is calculated based on objective variables typically available at the time of ICU admission in patients with liver disease: The MAP, WBC, bilirubin, and PT. This combination of variables reflects hepatic and extra-hepatic (circulatory and immune) dysfunction, which are validated risk factors for mortality in patients with cirrhosis[32-34]. This score performed better in our training cohort as a predictor for short-term mortality than other ICU- and liver-specific models, including the SOFA, CLIF-SOFA, and RFH scores, with excellent discriminative ability and calibration. In our validation cohort, it performed better than the RFH and was non-inferior to all others. In addition, the LIV-4 provides a survival probability score. This survival probability calculation may be useful for critical care, hepatology and surgical specialists when addressing goals and expectations of critical care with patients and their families. The APACHE methodology, APS, and SOFA were developed to assess the clinical course and predict survival of all-comers admitted to the ICU[9-11]. Liver-specific scores, such as the Child-Pugh Score, MELD, MELD-Na and CLIF-SOFA are used to grade severity of liver disease, predict 90-day mortality, allocate organs for transplantation, and define acute-on-chronic liver failure[1,12-15]. Liver-specific scores have been extrapolated for use as predictive models for mortality in the ICU, but have not performed better than ICU-specific scores[17-25]. In our study, the MELD and the CLIF-SOFA scores (both liver-specific scores and both with AUROCs of 0.81), performed better than ICU-specific scores, including the SOFA, APACHE III, and APS scores (AUROCs of 0.79, 0.76, 0.76, respectively). We postulate that the differences in our observations relate to critical care trends over time, with associated improved survival and lower event-deaths in more recent years. Our model was formulated in a more contemporary cohort than previous models and was subsequently prospectively validated, with objective variables that more accurately reflect current critical care challenges in the approach to the cirrhotic patient-most notably circulatory/adrenocortical dysfunction and infection/inflammation[32-35]. Variable mortality trends with time were also observed in the development of the updated RFH score[19]. Our mortality rates of 27.3% between 2008-2014 and 31.8% between 2015-2017 are similar to that of a comparable cohort from the Royal Free Hospital (2009-2012; 35.4%)[19], as well as the cohort of patients described in the development of the CLIF-SOFA score (2011; 29.7% in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure)[1].

The RFH score is a liver-specific ICU score that has been previously externally validated in several centers in Scotland[26]. Our study is the first in the United States to validate the updated RFH score, which performed in our cohort with an AUROC of 0.77. However, we found that the RFH score was limited in its generalizability as lactate and A-a gradient were not universally available on admission in our cohort. Lactate has been shown to be an independent predictor of mortality in cirrhotic patients[18,19,26,27,36,37] and in patients with acute liver failure[38] admitted to the ICU. However, lactate clearance has also been shown to be impaired by liver and extra-hepatic organ dysfunction, as evidenced by decreased clearance with increasing L-SOFA score[39], which suggests that lactate levels may not be reliable in cirrhotic patients. Similarly, arterial blood gas analysis and calculation of the A-a gradient is more likely to be collected in patients with respiratory failure necessitating mechanical ventilation, and is not universally available in patients admitted to the ICU as the precise FiO2 is often unknown. Finally, variceal hemorrhage as a reason for admission to the ICU was not an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality in our cohort. For these reasons, in an effort to create a widely applicable score for all cirrhotic patients admitted to the ICU, we did not include lactate, arterial blood gas analysis, or variceal hemorrhage in our new prognostic model. The LIV-4 performs with better discrimination and calibration in all patients with cirrhosis admitted to our ICU, independent of variceal hemorrhage, presence/grade of encephalopathy, and presence/degree of ascites.

In terms of limitations, patients were identified from the prospectively developed ICU APACHE IVb database and data was collected retrospectively. It is possible that all consecutive patients with cirrhosis were not captured with our retrospective methodology as a consequence of coding error, or if cirrhosis was not recognized as a pre-existing chronic health condition on admission to ICU. While internal prospective validation at our center suggests that the LIV-4 score will be widely applicable, we advocate for external, prospective analyses to be undertaken across diverse ICU settings in an effort to validate the clinical applicability of the score. Finally, it is important to recognize that, much as the APACHE scoring system has evolved to reflect progressive trends in the practice of critical care medicine, temporal study for re-calibration of LIV-4 will be necessary.

Patients with cirrhosis admitted to the ICU present unique clinical challenges for the clinician, and are best managed by a multidisciplinary team, comprised of specialists in both critical care and hepatology[8]. Prognostication of short-term survival is important in order to identify patients at highest risk for mortality in terms of allocation of resources, studies and interventions. We report the development and prospective validation of a new prognostic model for the prediction of inpatient transplant-free survival in a contemporary cohort of cirrhotic patients admitted to the ICU. This tool can be easily accessed online at http://riskcalc.org:3838/LIV-4/. If external validation is undertaken, the LIV-4 score could become a standard clinical tool in the ICU and maybe used as a means of stratifying critically ill patients with cirrhosis in clinical and translational research studies.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Critically ill patients with cirrhosis have higher mortality rates in the intensive care unit (ICU) than patients without chronic liver disease. Prognostication of short-term mortality is important in order to identify patients at highest risk of death. None of the currently available prognostic models have been widely accepted for use in cirrhotic patients in the ICU, perhaps due to complexity of calculation, or lack of universal variables readily available for these patients.

Research motivation

We believe a simple and widely applicable survival model can be developed, to guide therapeutic decision-making and contribute to cost-effective healthcare resource utilization.

Research objectives

To identify clinical and laboratory markers universally available at the time of ICU admission that best identify the likelihood of transplant-free survival in critically ill patients with cirrhosis.

Research methods

A new predictive model (the LIV-4 score) was developed retrospectively using logistic regression analysis from a large cohort of critically ill patients with cirrhosis admitted to a quaternary care liver transplant center ICU and was prospectively validated in a cohort of patients admitted to the same institution.

Research results

Our validated model for predicting mortality in cirrhotic patients on admission to the ICU performs better than previously published liver and ICU-specific scores.

Research conclusions

LIV-4 could become a standard clinical tool for patients with advanced liver disease in the ICU and could be used as a means of stratifying critically ill cirrhotic patients in clinical research studies.

Research perspectives

Survival modeling is an important tool for therapeutic decision-making as well as for research study design. The LIV-4 score was designed and validated prospectively in a single-center cohort. External, prospective validation is needed to determine widespread applicability and utility of the model.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent statement: The Cleveland Clinic Foundation Institutional Review Board waives the written consent for all retrospective medical record reviews done for research purposes (as the one done for this study) if the investigators can ensure there are adequate protections to maintain the data in a secure manner with access limited to the study team and if sharing or releasing identifiable data to any outside person or entity will not occur. For this reason, no Informed Consent Form was used for this study.

Conflict-of-interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest associated with any of the senior authors or other coauthors who contributed their efforts to this manuscript. All the authors have no conflict of interest related to the manuscript.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and American College of Gastroenterology.

Peer-review started: January 26, 2020

First decision: March 15, 2020

Article in press: May 19, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: de Mattos A, Iyngkaran P, Qi XS S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu MY

Contributor Information

Christina C Lindenmeyer, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States. lindenc@ccf.org.

Gianina Flocco, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States.

Vedha Sanghi, Department of Internal Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States.

Rocio Lopez, Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44106, United States.

Ahyoung J Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States.

Fadi Niyazi, Department of Internal Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States.

Neal A Mehta, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States.

Aanchal Kapoor, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States.

William D Carey, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States.

Eduardo Mireles-Cabodevila, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States.

Carlos Romero-Marrero, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, Durand F, Gustot T, Saliba F, Domenicali M, Gerbes A, Wendon J, Alessandria C, Laleman W, Zeuzem S, Trebicka J, Bernardi M, Arroyo V CANONIC Study Investigators of the EASL–CLIF Consortium. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1426–1437, 1437.e1-1437.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Brien AJ, Welch CA, Singer M, Harrison DA. Prevalence and outcome of cirrhosis patients admitted to UK intensive care: a comparison against dialysis-dependent chronic renal failure patients. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:991–1000. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nadim MK, Durand F, Kellum JA, Levitsky J, O'Leary JG, Karvellas CJ, Bajaj JS, Davenport A, Jalan R, Angeli P, Caldwell SH, Fernández J, Francoz C, Garcia-Tsao G, Ginès P, Ison MG, Kramer DJ, Mehta RL, Moreau R, Mulligan D, Olson JC, Pomfret EA, Senzolo M, Steadman RH, Subramanian RM, Vincent JL, Genyk YS. Management of the critically ill patient with cirrhosis: A multidisciplinary perspective. J Hepatol. 2016;64:717–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arroyo V, Moreau R, Jalan R, Ginès P EASL-CLIF Consortium CANONIC Study. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: A new syndrome that will re-classify cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S131–S143. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arroyo V, Moreau R, Kamath PS, Jalan R, Ginès P, Nevens F, Fernández J, To U, García-Tsao G, Schnabl B. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in cirrhosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16041. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jalan R, Saliba F, Pavesi M, Amoros A, Moreau R, Ginès P, Levesque E, Durand F, Angeli P, Caraceni P, Hopf C, Alessandria C, Rodriguez E, Solis-Muñoz P, Laleman W, Trebicka J, Zeuzem S, Gustot T, Mookerjee R, Elkrief L, Soriano G, Cordoba J, Morando F, Gerbes A, Agarwal B, Samuel D, Bernardi M, Arroyo V CANONIC study investigators of the EASL-CLIF Consortium. Development and validation of a prognostic score to predict mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1038–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jalan R, Gines P, Olson JC, Mookerjee RP, Moreau R, Garcia-Tsao G, Arroyo V, Kamath PS. Acute-on chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1336–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson JC, Wendon JA, Kramer DJ, Arroyo V, Jalan R, Garcia-Tsao G, Kamath PS. Intensive care of the patient with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1864–1872. doi: 10.1002/hep.24622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincent JL, de Mendonça A, Cantraine F, Moreno R, Takala J, Suter PM, Sprung CL, Colardyn F, Blecher S. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on "sepsis-related problems" of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1793–1800. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, Zimmerman JE, Bergner M, Bastos PG, Sirio CA, Murphy DJ, Lotring T, Damiano A. The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991;100:1619–1636. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.6.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270:2957–2963. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.24.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646–649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiesner R, Edwards E, Freeman R, Harper A, Kim R, Kamath P, Kremers W, Lake J, Howard T, Merion RM, Wolfe RA, Krom R United Network for Organ Sharing Liver Disease Severity Score Committee. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:91–96. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamath PS, Kim WR Advanced Liver Disease Study Group. The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) Hepatology. 2007;45:797–805. doi: 10.1002/hep.21563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim WR, Biggins SW, Kremers WK, Wiesner RH, Kamath PS, Benson JT, Edwards E, Therneau TM. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the liver-transplant waiting list. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1018–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leise MD, Kim WR, Kremers WK, Larson JJ, Benson JT, Therneau TM. A revised model for end-stage liver disease optimizes prediction of mortality among patients awaiting liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1952–1960. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen YC, Tian YC, Liu NJ, Ho YP, Yang C, Chu YY, Chen PC, Fang JT, Hsu CW, Yang CW, Tsai MH. Prospective cohort study comparing sequential organ failure assessment and acute physiology, age, chronic health evaluation III scoring systems for hospital mortality prediction in critically ill cirrhotic patients. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:160–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cholongitas E, Senzolo M, Patch D, Kwong K, Nikolopoulou V, Leandro G, Shaw S, Burroughs AK. Risk factors, sequential organ failure assessment and model for end-stage liver disease scores for predicting short term mortality in cirrhotic patients admitted to intensive care unit. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:883–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Theocharidou E, Pieri G, Mohammad AO, Cheung M, Cholongitas E, Agarwal B, Burroughs AK. The Royal Free Hospital score: a calibrated prognostic model for patients with cirrhosis admitted to intensive care unit. Comparison with current models and CLIF-SOFA score. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:554–562. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filloux B, Chagneau-Derrode C, Ragot S, Voultoury J, Beauchant M, Silvain C, Robert R. Short-term and long-term vital outcomes of cirrhotic patients admitted to an intensive care unit. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1474–1480. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834059cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juneja D, Gopal PB, Kapoor D, Raya R, Sathyanarayanan M, Malhotra P. Outcome of patients with liver cirrhosis admitted to a specialty liver intensive care unit in India. J Crit Care. 2009;24:387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh N, Gayowski T, Wagener MM, Marino IR. Outcome of patients with cirrhosis requiring intensive care unit support: prospective assessment of predictors of mortality. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:73–79. doi: 10.1007/s005350050047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai MH, Peng YS, Lien JM, Weng HH, Ho YP, Yang C, Chu YY, Chen YC, Fang JT, Chiu CT, Chen PC. Multiple organ system failure in critically ill cirrhotic patients. A comparison of two multiple organ dysfunction/failure scoring systems. Digestion. 2004;69:190–200. doi: 10.1159/000078789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wehler M, Kokoska J, Reulbach U, Hahn EG, Strauss R. Short-term prognosis in critically ill patients with cirrhosis assessed by prognostic scoring systems. Hepatology. 2001;34:255–261. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimmerman JE, Wagner DP, Seneff MG, Becker RB, Sun X, Knaus WA. Intensive care unit admissions with cirrhosis: risk-stratifying patient groups and predicting individual survival. Hepatology. 1996;23:1393–1401. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell J, McPeake J, Shaw M, Puxty A, Forrest E, Soulsby C, Emerson P, Thomson SJ, Rahman TM, Quasim T, Kinsella J. Validation and analysis of prognostic scoring systems for critically ill patients with cirrhosis admitted to ICU. Crit Care. 2015;19:364. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1070-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zauner C, Schneeweiss B, Schneider B, Madl C, Klos H, Kranz A, Ratheiser K, Kramer L, Lenz K. Short-term prognosis in critically ill patients with liver cirrhosis: an evaluation of a new scoring system. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:517–522. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang JT, Tsai MH, Tian YC, Jenq CC, Lin CY, Chen YC, Lien JM, Chen PC, Yang CW. Outcome predictors and new score of critically ill cirrhotic patients with acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:1961–1969. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrell FE, Jr, Califf RM, Pryor DB, Lee KL, Rosati RA. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA. 1982;247:2543–2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3:32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bajaj JS, O'Leary JG, Reddy KR, Wong F, Biggins SW, Patton H, Fallon MB, Garcia-Tsao G, Maliakkal B, Malik R, Subramanian RM, Thacker LR, Kamath PS North American Consortium For The Study Of End-Stage Liver Disease (NACSELD) Survival in infection-related acute-on-chronic liver failure is defined by extrahepatic organ failures. Hepatology. 2014;60:250–256. doi: 10.1002/hep.27077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bajaj JS, O'Leary JG, Reddy KR, Wong F, Olson JC, Subramanian RM, Brown G, Noble NA, Thacker LR, Kamath PS NACSELD. Second infections independently increase mortality in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis: the North American consortium for the study of end-stage liver disease (NACSELD) experience. Hepatology. 2012;56:2328–2335. doi: 10.1002/hep.25947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clària J, Stauber RE, Coenraad MJ, Moreau R, Jalan R, Pavesi M, Amorós À, Titos E, Alcaraz-Quiles J, Oettl K, Morales-Ruiz M, Angeli P, Domenicali M, Alessandria C, Gerbes A, Wendon J, Nevens F, Trebicka J, Laleman W, Saliba F, Welzel TM, Albillos A, Gustot T, Benten D, Durand F, Ginès P, Bernardi M, Arroyo V; CANONIC Study Investigators of the EASL-CLIF Consortium and the European Foundation for the Study of Chronic Liver Failure (EF-CLIF) Systemic inflammation in decompensated cirrhosis: Characterization and role in acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatology. 2016;64:1249–1264. doi: 10.1002/hep.28740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernández J, Escorsell A, Zabalza M, Felipe V, Navasa M, Mas A, Lacy AM, Ginès P, Arroyo V. Adrenal insufficiency in patients with cirrhosis and septic shock: Effect of treatment with hydrocortisone on survival. Hepatology. 2006;44:1288–1295. doi: 10.1002/hep.21352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tas A, Akbal E, Beyazit Y, Kocak E. Serum lactate level predict mortality in elderly patients with cirrhosis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124:520–525. doi: 10.1007/s00508-012-0208-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Funk GC, Doberer D, Kneidinger N, Lindner G, Holzinger U, Schneeweiss B. Acid-base disturbances in critically ill patients with cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2007;27:901–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cholongitas E, O'Beirne J, Betrossian A, Senzolo M, Shaw S, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Prognostic impact of lactate in acute liver failure. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:121–2; author reply 123. doi: 10.1002/lt.21383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sterling SA, Puskarich MA, Jones AE. The effect of liver disease on lactate normalization in severe sepsis and septic shock: a cohort study. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2015;2:197–202. doi: 10.15441/ceem.15.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.