This cohort study evaluates the independent risk factors associated with mortality of patients with COVID-19 requiring treatment in the intensive care unit in the Lombardy region of Italy.

Key Points

Question

What are the risk factors associated with mortality among critically ill patients with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 admitted to intensive care units in Lombardy, Italy?

Findings

In this cohort study that involved 3988 critically ill patients admitted from February 20 to April 22, 2020, the hospital mortality rate as of May 30 was 12 per 1000 patient-days after a median observation time of 70 days. In the subgroup of the first 1715 patients, 865 (50.4%) had been discharged from the intensive care unit, 836 (48.7%) had died in the intensive care unit, and 14 (0.8%) were still in the intensive care unit; 915 patients died in the hospital for overall hospital mortality of (53.4%).

Meaning

This study found that most critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the intensive care unit required invasive mechanical ventilation, and mortality rate and absolute mortality rate were high.

Abstract

Importance

Many patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are critically ill and require care in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Objective

To evaluate the independent risk factors associated with mortality of patients with COVID-19 requiring treatment in ICUs in the Lombardy region of Italy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective, observational cohort study included 3988 consecutive critically ill patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 referred for ICU admission to the coordinating center (Fondazione IRCCS [Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico] Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy) of the COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network from February 20 to April 22, 2020. Infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 was confirmed by real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction assay of nasopharyngeal swabs. Follow-up was completed on May 30, 2020.

Exposures

Baseline characteristics, comorbidities, long-term medications, and ventilatory support at ICU admission.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Time to death in days from ICU admission to hospital discharge. The independent risk factors associated with mortality were evaluated with a multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results

Of the 3988 patients included in this cohort study, the median age was 63 (interquartile range [IQR] 56-69) years; 3188 (79.9%; 95% CI, 78.7%-81.1%) were men, and 1998 of 3300 (60.5%; 95% CI, 58.9%-62.2%) had at least 1 comorbidity. At ICU admission, 2929 patients (87.3%; 95% CI, 86.1%-88.4%) required invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV). The median follow-up was 44 (95% CI, 40-47; IQR, 11-69; range, 0-100) days; median time from symptoms onset to ICU admission was 10 (95% CI, 9-10; IQR, 6-14) days; median length of ICU stay was 12 (95% CI, 12-13; IQR, 6-21) days; and median length of IMV was 10 (95% CI, 10-11; IQR, 6-17) days. Cumulative observation time was 164 305 patient-days. Hospital and ICU mortality rates were 12 (95% CI, 11-12) and 27 (95% CI, 26-29) per 1000 patients-days, respectively. In the subgroup of the first 1715 patients, as of May 30, 2020, 865 (50.4%) had been discharged from the ICU, 836 (48.7%) had died in the ICU, and 14 (0.8%) were still in the ICU; overall, 915 patients (53.4%) died in the hospital. Independent risk factors associated with mortality included older age (hazard ratio [HR], 1.75; 95% CI, 1.60-1.92), male sex (HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.31-1.88), high fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio2) (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.10-1.19), high positive end-expiratory pressure (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01-1.06) or low Pao2:Fio2 ratio (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.74-0.87) on ICU admission, and history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.28-2.19), hypercholesterolemia (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.02-1.52), and type 2 diabetes (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.01-1.39). No medication was independently associated with mortality (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.97-1.42; angiotensin receptor blockers HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.85-1.29).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this retrospective cohort study of critically ill patients admitted to ICUs in Lombardy, Italy, with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, most patients required IMV. The mortality rate and absolute mortality were high.

Introduction

As of June 16, 2020, 8 251 224 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections and 445 188 coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)–related deaths had been reported worldwide.1 Among active cases, 1.6% (54 593 of 3 503 249) are in severe or critical condition.

Lombardy, a region of Northern Italy, was the epicenter of the first COVID-19 outbreak in a western country.2 On April 22, 3940 of 69 092 laboratory-confirmed cases (5.7%) required admission to one of the intensive care units (ICUs) of the COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network.3 Knowledge of baseline patient characteristics and risk factors associated with ICU and hospital mortality is still limited. Male sex, hypertension, cardiovascular disorders, and type 2 diabetes are the most prevalent comorbidities, and they are associated with a high case fatality rate.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is typically less than 10%.4,6,7,8,10,11,12 It has been hypothesized that the use of drugs acting on the renin-angiotensin system may be associated with the course of the disease, because SARS-CoV-2 enters the host cells by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).6,13,14,15,16,17

Acute respiratory distress syndrome has been diagnosed in 40% to 96%6,7,8,12,18 of the patients admitted to the ICU. Need for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) varied widely between the different case series but is invariably associated with high mortality,4,5,6,8,10,18,19 with ICU mortality ranging from 16% to 78%.7,8,9,11,12,18,19,20 A prior study from the COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network5 reported an ICU mortality of 25.6% (15% aged 14-63 years; 36% aged 64-91 years); however, 58.2% of patients were still in the ICU at the end of follow-up.

We herein report ICU and hospital outcomes of the first 3988 patients critically ill with COVID-19 referred to the Coordinating Center (Fondazione IRCCS [Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico] Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy) of the COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network.2,5 Some data from the first 1591 patients have been previously reported.5 We describe the baseline characteristics of the patients, comorbidities, concomitant treatments at the time of hospital admission, mode and setting of ventilatory support, and the association of these characteristics with time to death.

Methods

Patients and Data Collection

The institutional ethics board of Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, approved this study and waived the need for informed consent from individual patients owing to the retrospective nature of the study. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

This retrospective, observational study enrolled all consecutive patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted to one of the Network ICUs from February 20 to April 22, 2020. To the best of our knowledge, all the critically ill patients requiring ICU admission in Lombardy have been referred to the Regional Coordinating Center. Laboratory confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 was defined as a positive result of real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction assay of nasal and pharyngeal swabs and, in selected cases, confirmation with reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction assay from lower respiratory tract aspirates.

The staff of the Regional Coordinating Center contacted each ICU of the Network daily by telephone and recorded on an electronic worksheet the demographic and clinical patient data. The following variables within the first 24 hours of ICU admission were recorded: age, sex, mode of respiratory support (IMV, noninvasive mechanical ventilation [NIV], oxygen mask), level of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio2), arterial partial pressure of oxygen (Pao2), Pao2:Fio2 ratio, use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and prone positioning. Preexisting comorbidities, long-term use of medications, and date of symptom onset were retrieved from the Regional Health System Database, which is based on the prescription of the general practitioners. The definitions of home intake of long-term medications and of each comorbidity, derived from the Regional Database, are presented in the eMethods in the Supplement.

The ICU and hospital outcomes of each patient were recorded on May 30, 2020. The interval from symptom onset to ICU admission, length of ICU stay, rate of reintubation, and rate of readmission to ICU were also evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are reported as frequencies (percentages with 95% CIs) and continuous variables as means (with SDs) or medians (with interquartile ranges [IQRs] and 95% CIs) according to distribution. Groups were compared with Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Benjamini and Hochberg correction for multiple comparison according to data distribution for continuous variables, and with Pearson χ2 test (Fisher exact test where appropriate) for categorical variables.

Life status was determined for all patients as of May 30, 2020, from the Regional Health Authority. Time-to-event techniques were used to analyze survival from ICU admission. Overall mortality rate was calculated per 1000 patient-days. The ICU and hospital mortality rates were calculated analogously, taking into account only time until ICU (or hospital) discharge.

Days from ICU admission to death (event) or May 30, 2020 (censoring), constituted the time of analysis. At the time of censoring, patients might be alive in the ICU, alive in hospital, or alive and discharged. For patients readmitted to the ICU after discharge, the first ICU admission was considered in the analysis.

We calculated Kaplan-Meier survival estimates and used the log-rank test to compare groups in terms of survival. The association of risk factors with time to death was assessed in univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models. The proportional hazard assumption was tested by plotting the Nelson-Aalen cumulative hazard function and Schoenfeld residuals test.21

Four multivariable models were developed for demographics (model 1), comorbidities (model 2), drugs (model 3), and respiratory parameters (model 4) using variables strongly associated with mortality at univariable analysis, known from previous literature to be strongly associated with outcome and not collinear. We used the Akaike information criterion to compare different regression models and select the most parsimonious model.

The final model included independent factors from models 1 to 3 only (model 4 was run on a subset of data owing to missing data), with no further selection. The number of patients with missing data were 0 for outcomes, 82 for drugs, 688 for comorbidities, 1053 for Pao2, 984 for Fio2, 1074 for Pao2:Fio2 ratio, and 958 for PEEP on ICU admission. Detailed information about missing data are reported in eFigure 1 in the Supplement.

A subgroup analysis was performed on the first 1715 patients, most of whom were included in a prior report.6 As of May 30, 2020, 14 (0.8%) of these patients were still in the ICU, and 865 (50.4%) had been discharged from the ICU. A second subgroup analysis was performed on the 1643 patients with hypertension to explore the potential role of ACE inhibitors and antihypertensive drugs in this subset. A third subgroup analysis was performed on the 350 patients treated with NIV in the ICU to assess the association of NIV with patient outcomes. R software, version 4.0 (R CoreTeam, 2020), and STATA computer software, version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC), were used for data analysis. Two-sided P < .05 indicated significance.

Results

Description of the Cohort

From a population of 4209 patients admitted to ICUs in Lombardy with suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection to April 22, 2020, we excluded 127 patients with negative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction findings for SARS-CoV-2 and 94 patients missing results of reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction for SARS-CoV-2. Data from 3988 patients (median age, 63 [IQR, 56-69] years) were analyzed. Table 1 shows the associations between demographic and baseline characteristics and mortality. Most patients were men (3188 [79.9%; 95% CI, 78.7%-81.1%]), with a median age of 63 (95% CI, 62-63; IQR, 55-69) years. Eight hundred patients were women (20.1%; 95% CI, 18.9%-21.3%]), with a median age of 64 (95% CI, 63-65; IQR, 57-70) years. Median time from symptom onset to ICU admission was 10 (95% CI, 9-10; IQR, 6-14) days. One thousand nine hundred and ninety-eight of 3300 patients (60.5%; 95% CI, 58.9%-62.2%) had at least 1 comorbidity. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity (1643 [42.1%; 95% CI, 40.5%-43.6%]), followed by hypercholesterolemia (545 [16.5%; 95% CI, 15.3%-17.8%]) and heart disease (533 [16.2%; 95% CI, 14.9%-17.4%]).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes of 3988 Patients With COVID-19 Admitted to the ICU in Lombardy, Italy.

| Characteristica | No. of patients (n = 3988) | No. of deaths (n = 1926) | Mortality rate per 1000 patient-days | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||||

| <56 | 997 | 245 | 4.5 (3.9-5.0) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 56-63 | 997 | 416 | 9.2 (8.3-10.1) | 1.91 (1.63-2.24) | <.001 |

| 64-69 | 997 | 562 | 15.6 (14.3-16.9) | 2.98 (2.56-3.46) | <.001 |

| >69 | 997 | 703 | 25.2 (23.4-27.1) | 4.25 (3.68-4.92) | <.001 |

| Men | 3188 | 1580 | 12.2 (11.6-12.9) | 1.22 (1.08-1.37) | <.001 |

| Women | 800 | 346 | 9.9 (8.8-10.9) | 0.73 (0.82-0.92) | <.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| None | 1302 | 490 | 7.7 (7.0-8.4) | 0.55 (0.49-0.61) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 1643 | 962 | 15.8 (14.8 -16.8) | 1.68 (1.53-1.84) | <.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 545 | 376 | 22.4 (20.2-24.8) | 1.90 (1.70- 2.14) | <.001 |

| Heart diseaseb | 533 | 342 | 19.4 (17.4-21.5) | 1.66 (1.48- 1.87) | <.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 514 | 328 | 19.3 (17.3-21.5) | 1.66 (1.47- 1.88) | <.001 |

| Malignant neoplasmc | 331 | 202 | 17.3 (15.0-19.8) | 1.45 (1.25-1.68) | <.001 |

| COPD | 93 | 67 | 25.4 (19.7-32.2) | 2.03 (1.59-2.59) | <.001 |

| CKD | 87 | 71 | 39.3 (30.7-49.6) | 2.78 (2.19-3.53) | <.001 |

| Liver disease | 86 | 42 | 11.4 (8.3-15.5) | 1.03 (0.76-1.39) | .87 |

| Other disease | 501 | 274 | 13.7 (12.1-15.4) | 1.19 (1.04-1.35) | .01 |

| Time from onset of symptoms to ICU admission, d | |||||

| <6 | 922 | 510 | 14.4 (13.1-15.7) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 6-9 | 921 | 405 | 9.8 (8.8-10.8) | 0.71 (0.62-0.81) | <.001 |

| 10-14 | 921 | 411 | 10.2 (9.3-11.3) | 0.73 (0.64-0.83) | <.001 |

| >14 | 921 | 455 | 13.1 (11.9-14.4) | 0.84 (0.74-0.95) | .006 |

| Length of ICU stay, d | |||||

| <6 | 994 | 615 | 22.8 (21.0-24.7) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 6-11 | 993 | 528 | 14.3 (13.1-15.6) | 0.59 (0.52-0.66) | <.001 |

| 12-21 | 994 | 475 | 11.0 (10.1-12.1) | 0.42 (0.38-0.48) | <.001 |

| >21 | 993 | 308 | 5.5 (4.9-6.1) | 0.23 (0.20-0.27) | <.001 |

| Length of IMV, d | |||||

| <6 | 634 | 480 | 37.8 (34.5-41.3) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 6-9 | 634 | 413 | 21.8 (19.7-23.9) | 0.52 (0.46-0.60) | <.001 |

| 10-17 | 634 | 384 | 16.7 (15.1-18.5) | 0.32 (0.37-0.43) | <.001 |

| >17 | 633 | 368 | 12.9 (11.6-14.3) | 0.29 (0.25-0.41) | <.001 |

| Length of hospital stay, d | |||||

| <15 | 925 | 837 | 77.7 (72.7-83.3) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 15-27 | 924 | 565 | 16.9 (15.5-18.4) | 0.21 (0.19-0.24) | <.001 |

| 28-48 | 924 | 268 | 5.4 (4.7-5.9) | 0.07(0.06-0.08) | <.001 |

| >48 | 924 | 58 | 0.9 (0.7-1.2) | 0.01 (0.01-0.02) | <.001 |

| Ventilation on ICU admission | |||||

| Respiratory support | 76 | 13 | 3.3 (1.7-5.6) | 1 | |

| NIV | 350 | 127 | 7.4 (6.1-8.7) | 2.36 (1.33-4.17) | .003 |

| IMV | 2929 | 1514 | 13.0 (12.4-13.7) | 3.77 (2.19-6.51) | <.001 |

| Pao2, mm Hg | |||||

| <76 | 734 | 404 | 14.9 (13.5-16.5) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 76-93 | 734 | 381 | 13.2 (11.9-14.6) | 0.89 (0.77-1.02) | .10 |

| 94-127 | 734 | 341 | 10.7 (9.6-11.9) | 0.74 (0.64-0.85) | <.001 |

| >127 | 733 | 337 | 10.4 (9.3-11.6) | 0.73 (0.63-0.84) | <.001 |

| Fio2, % | |||||

| <60 | 751 | 276 | 7.5 (6.6-8.4) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 60-69 | 751 | 373 | 11.6 (10.4-12.8) | 1.46 (1.25-1.71) | <.001 |

| 70-85 | 751 | 344 | 10.9 (9.8-12.1) | 1.35 (1.16-1.59) | <.001 |

| >85 | 751 | 501 | 22.5 (20.6-24.6) | 2.49 (2.15-2.89) | <.001 |

| Pao2:Fio2 ratio | |||||

| <103 | 729 | 461 | 20.2 (18.4-22.1) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 103-144 | 728 | 384 | 13.6 (12.2-14.9) | 0.7 (0.61-0.80) | <.001 |

| 145-203 | 729 | 352 | 11.3 (10.1-12.6) | 0.6 (0.53-0.69) | <.001 |

| >203 | 728 | 259 | 7.1 (6.2-7.9) | 0.41 (0.35-0.48) | <.001 |

| PEEP, cm H2O | |||||

| <10 | 758 | 364 | 12.2 (10.9-13.5) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 10-12 | 757 | 343 | 10.6 (9.5-11.7) | 0.92 (0.79-1.06) | .25 |

| 13-15 | 758 | 402 | 13.3 (12.1-14.7) | 1.15 (1.0-1.33) | .049 |

| >15 | 757 | 412 | 13.3 (12.2-14.6) | 1.19 (1.03-1.37) | .02 |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; Fio2, fraction of inspired oxygen; HR, hazard ratio; ICU, intensive care unit; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; NA, not applicable; NIV, noninvasive mechanical ventilation; Pao2, arterial partial pressure of oxygen; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure.

Continuous variables were divided in quartiles and compared using the z test from the Cox proportional hazards regression models.

Includes cardiomyopathy and heart failure.

Includes active neoplasia and neoplasia in remission.

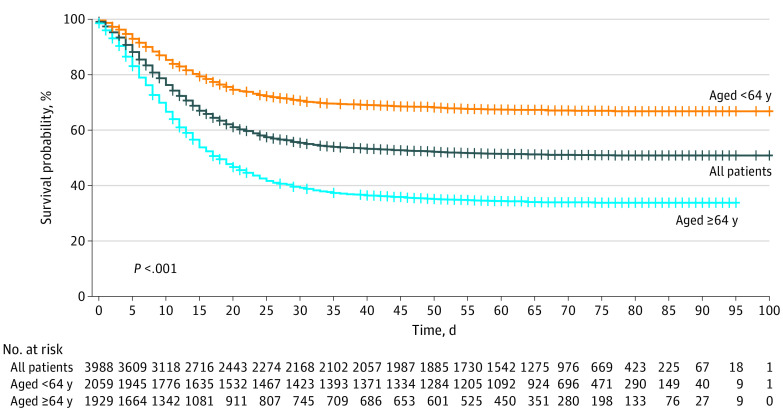

Observation Time and Main Outcomes

Cumulative observation time was 164 305 patient-days from ICU admission to end of follow-up for the 3988 patients (median observation time, 70 [range, 38-112] days; IQR, 61-70 days). After a median follow-up of 69 (IQR, 60-78; range, 38-100) days, there were 1926 deaths (overall mortality, 48.3%) for a mortality rate of 12 (95% CI, 11-12) per 1000 patient-days (Figure). There were 1769 ICU deaths (44.3%), for an ICU mortality rate of 27 (95% CI, 26-29) per 1000 patient-days. At the time of censoring, 91 patients (2.3%; 95% CI, 1.9%-2.8%) were still in the ICU, and 2049 (51.4%; 95% CI, 49.8%-52.9%) had been discharged from the ICU. Among the latter, 1480 patients (37.1%; 95% CI, 35.6%-38.6%) had been discharged from the hospital and 501 (12.6%; 95% CI, 11.6%-13.6%) were still hospitalized; the mortality rate after discharge from the ICU was 2 (95% CI, 1-2) per 1000 patient-days.

Figure. Kaplan-Meier Analysis of Survival of Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit.

Survival is reported for the overall group and stratified by median age (<64 or ≥64 years).

Distribution of patients’ outcomes by ICU admission date is presented in the eFigure 2 in the Supplement. Median ICU stay was 12 (IQR, 6-21; range, 0-87) days, and the median duration of mechanical ventilation was 10 (IQR, 6-17; range, 0-87) days. Median length of stay in hospital was 28 (IQR, 15-48; range, 0-120) days.

Of the 2049 patients discharged from the ICU, 134 (6.5%) were readmitted to the ICU after discharge. Sixty-four of 3857 patients (1.7%) underwent extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support during the ICU stay, of whom 40 died (62.5%), 13 were discharged home (20.3%), and 11 were still hospitalized (17.2%).

At ICU admission, 2929 of 3355 patients (excluding 633 with missing data) underwent intubation (87.3%; 95% CI, 86.1%-88.4%). Three hundred and fifty patients underwent noninvasive respiratory support with NIV (10.4%; 95% CI, 9.4%-11.5%), which in most cases consisted of continuous positive air pressure delivered through a helmet or a standard oxygen mask (76 of 3355 patients [2.3%]).

Univariable Analysis

A 10-year increase in age was significantly associated with mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.86; 95% CI, 1.76-1.96; P < .001). Patients 64 years or older had significantly decreased survival probability compared with younger patients (Figure).

Hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, heart disease, diabetes, malignant neoplasm, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and all the studied medications taken at home before entering the hospital were associated with increased mortality at univariable analysis (Table 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement). A 10% increase in Fio2 on the first day of ICU admission was associated with increased mortality (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.20-1.27; P < .001), whereas a 100-point increase in Pao2:Fio2 ratio decreased by 44% the hazard for mortality (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.61-0.71; P < .001).

Multivariable Analysis

At multivariable analysis, a 10-year increase in age (HR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.60 -1.92) and male sex (HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.31-1.88) were significantly associated with mortality (Table 2 and eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Among comorbidities, history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.28-2.19), hypercholesterolemia (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.02-1.52), and diabetes (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.01-1.39) were significantly associated with mortality. No long-term use of a medication was independently associated with mortality after controlling for other factors (ACE inhibitors HR, 1.17 [95% CI, 0.97-1.42]; angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs] HR, 1.05 [95% CI, 0.85-1.29]). Decreased PEEP (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01-1.06) and Fio2 (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.10-1.19) and increased Pao2:Fio2 ratio (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.74-0.87) at ICU admission were independently associated with improved survival.

Table 2. Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Analysis of Factors Associated With Mortality.

| Variable | Category (description) | Multivariable HR (95% CI) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 10-y Increments | 1.75 (1.60-1.92) | <.001 |

| Men | Men vs women | 1.57 (1.31-1.88) | <.001 |

| Respiratory support | Spontaneous breathing vs NIV | 1.81 (0.57-5.76) | .32 |

| Invasive MV vs NIV | 1.24 (1.00-1.55) | .052 | |

| Hypertension | Yes vs no | 0.99 (0.81-1.22) | .93 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | Yes vs no | 1.25 (1.02-1.52) | .03 |

| Heart disease | Yes vs no | 1.08 (0.91-1.29) | .38 |

| Type 2 diabetes | Yes vs no | 1.18 (1.01-1.39) | .04 |

| Malignancy | Yes vs no | 1.09 (0.92-1.28) | .33 |

| COPD | Yes vs no | 1.68 (1.28-2.19) | <.001 |

| ACE inhibitor therapy | Yes vs no | 1.17 (0.97-1.42) | .10 |

| ARB therapy | Yes vs no | 1.05 (0.85-1.29) | .64 |

| Statin | Yes vs no | 0.98 (0.81-1.20) | .87 |

| Diuretic | Yes vs no | 1.10 (0.91-1.32) | .32 |

| PEEP at admission | 1-cm H2O increments | 1.04 (1.01-1.06) | .009 |

| Fio2 at admission | 10% Increments | 1.14 (1.10-1.19) | <.001 |

| Pao2/Fio2 at admission | 100-U increments | 0.80 (0.74-0.87) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Fio2, fraction of inspired oxygen; HR, hazard ratio; IMV, Invasive mechanical ventilation; MV, mechanical ventilation; NIV, noninvasive mechanical ventilation; Pao2, arterial partial pressure of oxygen; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure.

Calculated using the z test from Cox proportional hazards regression models.

Subgroup Analyses

In the subgroup analysis of the first 1715 patients (minimum follow-up of 73 days), the hospital mortality was 915 patients (53.4%; 95% CI, 50.9%-55.7%), with 836 (48.7%; 95% CI, 46.4%-51.1%) dying in the ICU and 79 (4.6%; 95% CI, 3.7%-5.7%) dying after ICU discharge. Table 3 shows the univariable associations of baseline characteristics and comorbidities in this subgroup. As of May 30, 2020, 14 patients (0.8%) were still in the ICU and 127 (7.4%) were still hospitalized; the median observation time was 80 (range, 76-112) days. The median ICU length of stay of patients who died in the ICU was 10 (IQR, 5-16) days; for those discharged from the ICU, 15 (IQR, 8-24) days.

Table 3. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes of the First 1715 Patients.

| Variable | Overalla | ICU | Hospital | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death in ICU | Discharged from ICU | Still in ICU | P valueb | Death in hospital | Discharged from hospital | Still in hospital | P valueb | ||

| All patients | 1715 (100) | 836 (48.7) | 865 (50.4) | 14 (0.8) | .50 | 915 (53.4) | 673 (39.2) | 127 (7.4) | .50 |

| Men | 1398/1715 (81.5) | 700 (50.1) | 688 (49.2) | 10 (0.7) | .03 | 763 (54.6) | 534 (38.2) | 101 (7.2) | .046 |

| Women | 317/1715 (18.5) | 136 (42.9) | 177 (55.8) | 4 (1.3) | 152 (47.9) | 139 (43.8) | 26 (8.2) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 64 (56-70) | 68 (62-73) | 59 (52-66) | 62 (52-65) | <.001 | 68 (62-73) | 58 (51-64) | 62 (55-67) | <.001 |

| Comorbidities | 1078/1652 (65.3) | 594 (55.1) | 474 (44.0) | 10 (0.9) | <.001 | 653 (60.6) | 357 (33.1) | 68 (6.3) | <.001 |

| None | 574/1652 (34.7) | 211 (36.8) | 359 (62.5) | 4 (0.7) | <.001 | 228 (39.7) | 292 (50.9) | 54 (9.4) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 890/1703 (52.3) | 500 (56.2) | 382 (42.9) | 8 (0.9) | <.001 | 551 (61.9) | 283 (31.8) | 56 (6.3) | <.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 302/1652 (18.3) | 191 (63.2) | 110 (36.4) | 1 (0.3) | <.001 | 214 (70.9) | 74 (24.5) | 14 (4.6) | <.001 |

| Heart diseasec | 318/1652 (19.2) | 198 (62.3) | 117 (36.8) | 3 (0.9) | <.001 | 224 (70.4) | 76 (23.9) | 18 (5.7) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 284/1652 (17.2) | 182 (64.1) | 100 (35.2) | 2 (0.7) | <.001 | 201 (70.8) | 66 (23.2) | 17 (6.0) | <.001 |

| Malignant neoplasmd | 191/1652 (11.6) | 113 (59.2) | 78 (40.8) | 0 | .004 | 122 (63.9) | 59 (30.9) | 10 (5.2) | .005 |

| COPD | 58/1652 (3.5) | 39 (67.2) | 19 (32.8) | 0 | .007 | 45 (77.6) | 11 (19.0) | 2 (3.4) | <.001 |

| CKD | 52/1652 (3.1) | 41 (78.8) | 11 (21.2) | 0 | <.001 | 44 (84.6) | 7 (13.5) | 1 (1.9) | <.001 |

| Liver disease | 45/1652 (2.7) | 19 (42.2) | 26 (57.8) | 0 | .43 | 21 (46.7) | 20 (44.4) | 1 (2.2) | .79 |

| Other disease | 271/1652 (16.4) | 141 (52.0) | 128 (47.2) | 2 (0.7) | .26 | 155 (57.2) | 98 (36.2) | 18 (6.6) | .21 |

| Time from onset of symptoms to ICU admission, median (IQR), d | 8 (4-11) | 7 (4-10) | 8 (5-11) | 9 (4-11) | .14 | 7 (4-10) | 8 (5-11) | 8 (4-11) | .07 |

| No. of patients | 1588 | 769 | 807 | 12 | NA | 844 | 631 | 113 | NA |

| Length of ICU stay, median (IQR), d | 12 (7-20) | 10 (5-16) | 15 (8-24) | 76 (74-80) | <.001 | 10 (5-16) | 14 (8-22) | 33 (18-54) | <.001 |

| No. of patients | 1711 | 836 | 861 | 14 | NA | 915 | 669 | 127 | NA |

| Length of hospital stay, median (IQR), d | 22 (12-42) | 12 (8-19) | 39 (24-61) | 79 (74-84) | <.001 | 13 (8-20) | 37 (23-53) | 84 (79-88) | <.001 |

| No. of patients | 1618 | 766 | 838 | 14 | NA | 838 | 658 | 122 | NA |

| Length of mechanical ventilation, median (IQR), d | 10 (6-16) | 9 (5-15) | 12 (7-18) | 74 (73-78) | <.001 | 9 (5-15) | 11 (7-17) | 20 (13-65) | <.001 |

| No. of patients | 1171 | 787 | 370 | 14 | NA | 812 | 297 | 62 | NA |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number/total number (percentage) of patients for overall population and number (percentage) of row total for other columns.

Calculated for death vs discharge using Wilcoxon rank sum tests or χ2 test according to continuous or categorical variables.

Includes cardiomyopathy and heart failure.

Includes active neoplasia and neoplasia in remission.

In the subgroup of 1643 patients with a history of hypertension, long-term home treatment with ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, statins, and diuretics was associated with higher mortality at univariable analysis (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The subgroup of 350 patients initially treated with NIV had lower levels of PEEP (eTable 1 in the Supplement) and a lower hazard for mortality (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.52-0.75; P < .001) than patients treated with IMV. The 151 patients initially treated noninvasively and subsequently undergoing intubation (after a median of 3 [IQR, 2-4; range, 0-15] days) had a significantly lower chance of survival compared with the 199 patients who continued to undergo NIV during the entire ICU stay (HR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.43-1.98; P < .001). The mortality of the patients undergoing subsequent intubation was similar to that for the patients who were treated with mechanical ventilation for ICU admission (HR for IMV vs NIV failure, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.95-1.53; P = .12). eTable 1 and eFigure 4 in the Supplement show the overall survival data for patients in this subgroup.

Discussion

In a cohort of 3988 critically ill patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted to an ICU during the first 2 months of the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy, the estimated ICU and hospital mortality rates were 27 and 12 per 1000 patient-days, respectively. In the subset of the first 1715 patients, ICU and hospital mortality were 48.8% and 53.4%, respectively. This mortality is almost double that described in the initial report,6 in which the ICU mortality was 25.6% but 58.2% of the patients were still in the ICU at the end of follow-up. These sobering statistics highlight the long ICU stays, prolonged need for respiratory support, and high mortality of COVID-19 in critically ill patients.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, many patients required ICU admission in a limited period.2,22 Hence, the ICU capacity had to be rapidly increased by establishing a network of COVID-19 ICUs in many hospitals. Experience in the treatment of patients with acute respiratory failure and the physician-to-patient and nurse-to-patient ratios varied widely among the centers, and this might have had an effect on patient outcomes.23,24 Mortality of patients critically ill with COVID-19 varies significantly among the published case series, ranging from 16% to 78%.7,8,10,11,12,18,19,20 This wide variability can be explained by different case mixes, different organization, availability of ICU beds among different countries, and different lengths of follow-up. In a case series of ICU patients in China, 28-day ICU mortality was 39% for the entire ICU population (344 patients) but reached 97% in the subgroup of 100 patients requiring IMV.9 In the case series of critically ill patients from Washington State18 and the Seattle region,12 71% and 75% of patients required IMV, respectively. Mortality calculated with a minimum follow-up of 12 days was 67% in Washington State; with a minimum follow-up of 14 days, 50%.

Importantly, patients included in our series were the sickest patients, those treated in high-intensity (level 3) areas, as demonstrated by the very high proportion of patients (87.3%) undergoing IMV at ICU admission. Many more patients in Italy, not described herein, have been treated in lower-intensity (level 2) areas, created ad hoc for the COVID-19 crisis, with extended monitoring and noninvasive respiratory support.

Our findings confirm that survival of critically ill patients with COVID-19 is particularly low for older men requiring IMV and with preexisting comorbidities. Hypertension was the most frequent comorbidity, and patients with hypertension had significantly decreased survival. Despite this, in the multivariable analysis, hypertension was not an independent factor associated with mortality. Conversely, a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes, although affecting a smaller percentage of patients, were independently associated with mortality.

The pathophysiology of acute respiratory failure in patients with COVID-19 is poorly understood. Some reports show a significant mismatch between the degree of hypoxemia and a relatively minor compromise of respiratory system compliance.25 This mismatch may indicate that the optimal setting of mechanical ventilation in these patients may be different from that commonly applied in usual forms of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Levels of PEEP applied in our patients at ICU admission were higher than those reported for the management of moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome in the pre–COVID-19 era.26 High PEEP levels and Fio2 and low Pao2:Fio2 ratio at ICU admission were all independent factors associated with mortality.

Data on the effect of drugs acting on the renin-angiotensin system are of particular interest because ACE2 is the primary receptor for SARS-CoV-2 entry into the host cells.17 Preclinical data support the hypothesis that long-term intake of ACE inhibitors, ARBs, statins, corticosteroids, and hypoglycemic agents may increase susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection by favoring viral replication owing to upregulation of ACE2 receptors.27,28,29,30,31 On the other hand, in patients with COVID-19, these same drugs may theoretically improve the clinical course by rebalancing the dysregulated renin-angiotensin system and thus reducing vasoconstriction, inflammation, and oxidation. In a recent large case series, mortality of patients with hypertension taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs was higher than that of patients with hypertension not taking these drugs, but no statistic confirmed the association between chronic therapy with ACE inhibitors or ARBs and mortality.10 In our patients, long-term treatment with ACE inhibitors, ARBs, β-blockers, statins, diuretics, antiplatelet drugs, and anticoagulants before ICU admission was associated with higher mortality in an unadjusted analysis only. This finding should be interpreted with caution, because unmeasured confounders could explain this observation, as demonstrated by the fact that the multivariable analysis did not confirm the association between any home therapies and increased mortality.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective study based on data mainly collected by telephone primarily for clinical purposes. We were able to cross-link demographic data from other health care databases; however, this was mainly a real-life database made for operational reasons. We could not assess the effect of other important variables, such as weight, body mass index, smoking history, and respiratory system compliance. Second, some variables have missing data (eFigure 1 in the Supplement), mainly owing to the reasons mentioned above. Third, preexisting comorbidities and chronic medications were retrieved from the regional health system database; therefore, the severity of the comorbidities and patient compliance with medical prescriptions could not be evaluated. Moreover, we do not have information on how many patients maintained their long-term medication regimens during the ICU stay, which may be relevant, particularly for drugs acting on the renin-angiotensin system.

In addition, another important limitation concerns some peculiar organizational aspects of intensive care services of the Italian health care system. During this crisis, we increased the total capacity of both our higher-intensity (level 3) and lower-intensity (level 2) areas to increase our potential for respiratory support. All patients with COVID-19 undergoing intubation were treated in level 3 areas and are described in this report, whereas most patients who did not undergo intubation were treated in level 2 areas. For these reasons, we believe that our data provide important insights about patients requiring IMV but should not be extrapolated to the population of patients requiring other forms of advanced noninvasive respiratory support.

Conclusions

SARS-CoV-2 represents a massive challenge for health care systems and the ICUs in Italy and throughout the world.2 A high volume of patients with the same disease required access to intensive treatments at the same time. Until effective and specific therapies are available, supportive care is the mainstay of treatment for critically ill patients.32,33 Providing this care at a high-quality level for the high volume of patients to treat is a challenge for all health care systems.

eMethods. Definitions.

eFigure 1. Missing Data

eFigure 2. Outcomes According to ICU Admission Date

eFigure 3. Multivariable Model Including Baseline Characteristics, Comorbidities, Medications, and Physiological Variables at Admission

eFigure 4. Survival According to Use of Noninvasive Ventilation at Admission

eTable 1. Different Characteristics of Patients According to Noninvasive Ventilation or Invasive Mechanical Ventilation at Admission

eTable 2. Previous Medication Use in the Overall Population and in the Subpopulation of Patients With History of Hypertension

References

- 1.Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic. Updated July 3, 2020. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus

- 2.Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA. Published online March 13, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lombardia Notizie Online. Posted November 7, 2019. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.regione.lombardia.it/wps/portal/istituzionale/HP/lombardia-notizie

- 4.Du RH, Liu LM, Yin W, et al. Hospitalization and critical care of 109 decedents with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-225OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. ; COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network . Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574-1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. ; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19 . Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Lu X, Li Y, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of 344 intensive care patients with COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(11):1430-1434. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0736LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. ; and the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium . Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myers LC, Parodi SM, Escobar GJ, Liu VX. Characteristics of hospitalized adults with COVID-19 in an integrated health care system in California. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2195-2198. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. COVID-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region—case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2012-2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anguiano L, Riera M, Pascual J, Soler MJ. Circulating ACE2 in cardiovascular and kidney diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(30):3231-3241. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170414162841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz JH. Hypothesis: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may increase the risk of severe COVID-19. J Travel Med. 2020;27(3):taaa041. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ortiz-Pérez JT, Riera M, Bosch X, et al. Role of circulating angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction: a prospective controlled study. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(5):259-260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271-280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612-1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475-481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. 2nd ed Wiley; 2002. doi: 10.1002/9781118032985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carenzo L, Costantini E, Greco M, et al. Hospital surge capacity in a tertiary emergency referral centre during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(7):928-934. doi: 10.1111/anae.15072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. ; PROTOCETIC Group . Compliance with triage to intensive care recommendations. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(11):2132-2136. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200111000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robert R, Reignier J, Tournoux-Facon C, et al. ; Association des Réanimateurs du Centre Ouest Group . Refusal of intensive care unit admission due to a full unit: impact on mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(10):1081-1087. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0729OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marini JJ, Gattinoni L. Management of COVID-19 respiratory distress. JAMA. Published online April 24, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al. ; LUNG SAFE Investigators; ESICM Trials Group . Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315(8):788-800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111(20):2605-2610. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishiyama Y, Gallagher PE, Averill DB, Tallant EA, Brosnihan KB, Ferrario CM. Upregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 after myocardial infarction by blockade of angiotensin II receptors. Hypertension. 2004;43(5):970-976. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000124667.34652.1a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang F, Yang J, Zhang Y, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin 1-7: novel therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11(7):413-426. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karram T, Abbasi A, Keidar S, et al. Effects of spironolactone and eprosartan on cardiac remodeling and angiotensin-converting enzyme isoforms in rats with experimental heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(4):H1351-H1358. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01186.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sánchez-Aguilar M, Ibarra-Lara L, Del Valle-Mondragón L, et al. Rosiglitazone, a ligand to PPARγ, improves blood pressure and vascular function through renin-angiotensin system regulation. PPAR Res. 2019;2019:1371758. doi: 10.1155/2019/1371758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):854-887. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Definitions.

eFigure 1. Missing Data

eFigure 2. Outcomes According to ICU Admission Date

eFigure 3. Multivariable Model Including Baseline Characteristics, Comorbidities, Medications, and Physiological Variables at Admission

eFigure 4. Survival According to Use of Noninvasive Ventilation at Admission

eTable 1. Different Characteristics of Patients According to Noninvasive Ventilation or Invasive Mechanical Ventilation at Admission

eTable 2. Previous Medication Use in the Overall Population and in the Subpopulation of Patients With History of Hypertension