Abstract

The N-localizer and the Sturm-Pastyr localizer are two technologies that facilitate image-guided stereotactic surgery. Both localizers enable the geometric transformation of tomographic image data from the two-dimensional coordinate system of a medical image into the three-dimensional coordinate system of the stereotactic frame. Monte Carlo simulations reveal that the Sturm-Pastyr localizer is less accurate than the N-localizer in the presence of image noise.

Keywords: stereotactic surgery, stereotactic radiosurgery, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, n-localizer, sturm-pastyr localizer, monte carlo, image-guided surgery, image-guided radiosurgery, deep brain stimulation

Introduction

The N-localizer was introduced in 1979 [1], and the Sturm-Pastyr localizer was introduced in 1983 [2]. Both localizers enable the geometric transformation of tomographic image data from the two-dimensional  coordinate system of a medical image into the three-dimensional

coordinate system of a medical image into the three-dimensional  coordinate system of the stereotactic frame. Geometric transformation requires calculations that differ substantially between the two localizers in ways that impact the accuracy of the calculations when the effects of image noise are considered.

coordinate system of the stereotactic frame. Geometric transformation requires calculations that differ substantially between the two localizers in ways that impact the accuracy of the calculations when the effects of image noise are considered.

Technical report

Geometric transformation requires the calculation of  coordinates in the three-dimensional coordinate system of the stereotactic frame. The following presentation discusses the calculation of only the

coordinates in the three-dimensional coordinate system of the stereotactic frame. The following presentation discusses the calculation of only the  -coordinate because the calculation of the

-coordinate because the calculation of the  coordinates is trivial due to features of the N-localizer and Sturm-Pastyr localizer. Specifically, the N-localizer includes two vertical rods that have fixed values of

coordinates is trivial due to features of the N-localizer and Sturm-Pastyr localizer. Specifically, the N-localizer includes two vertical rods that have fixed values of  and

and  , and the Sturm-Pastyr localizer includes one vertical rod that has fixed values of

, and the Sturm-Pastyr localizer includes one vertical rod that has fixed values of  and

and  .

.

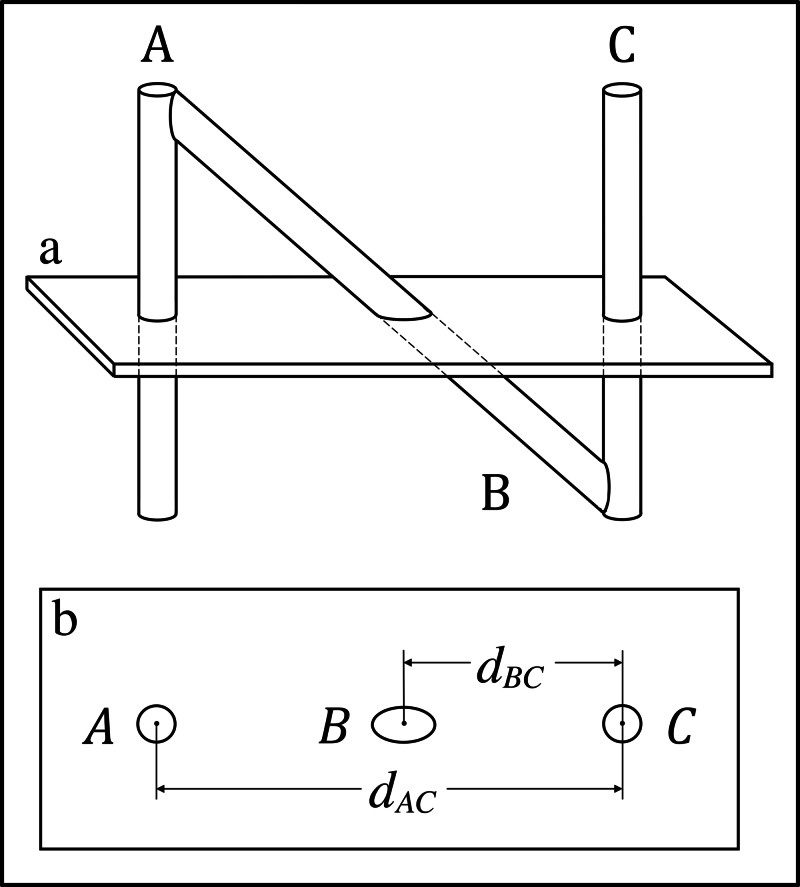

Figure 1 depicts the N-localizer that comprises two vertical rods and one diagonal rod. For the N-localizer, calculation of the  -coordinate of the point of intersection of the cylindrical axis of rod

-coordinate of the point of intersection of the cylindrical axis of rod  with the tomographic section is performed via linear interpolation between the two ends of rod

with the tomographic section is performed via linear interpolation between the two ends of rod  according to the following equation [3].

according to the following equation [3].

|

In this equation,  and

and  are distances measured in the

are distances measured in the  coordinate system of the medical image,

coordinate system of the medical image,  is the

is the  -coordinate of the top of rod

-coordinate of the top of rod  , and

, and  is the

is the  -coordinate of the bottom of rod

-coordinate of the bottom of rod  . The numeric values for

. The numeric values for  and

and  are established by the manufacturing specifications for the N-localizer. The fraction

are established by the manufacturing specifications for the N-localizer. The fraction  is dimensionless, and hence the units of

is dimensionless, and hence the units of  are the units of

are the units of  and

and  that are specified by the manufacturer. For this reason, calculations for the N-localizer do not require the specification of the pixel size for the medical image [3,4].

that are specified by the manufacturer. For this reason, calculations for the N-localizer do not require the specification of the pixel size for the medical image [3,4].

Figure 1. The N-Localizer and its Intersection with a Tomographic Section.

Side view of the N-localizer. A tomographic section intersects rods

Side view of the N-localizer. A tomographic section intersects rods  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.  Tomographic image. The intersection of the tomographic section with rods

Tomographic image. The intersection of the tomographic section with rods  ,

,  , and

, and  creates fiducial circles

creates fiducial circles  and

and  and fiducial ellipse

and fiducial ellipse  in the tomographic image. The distance

in the tomographic image. The distance  between the centers of ellipse

between the centers of ellipse  and circle

and circle  and the distance

and the distance  between the centers of circles

between the centers of circles  and

and  are used to calculate the

are used to calculate the  -coordinate of the point of intersection of the cylindrical axis of rod

-coordinate of the point of intersection of the cylindrical axis of rod  with the tomographic section [3].

with the tomographic section [3].

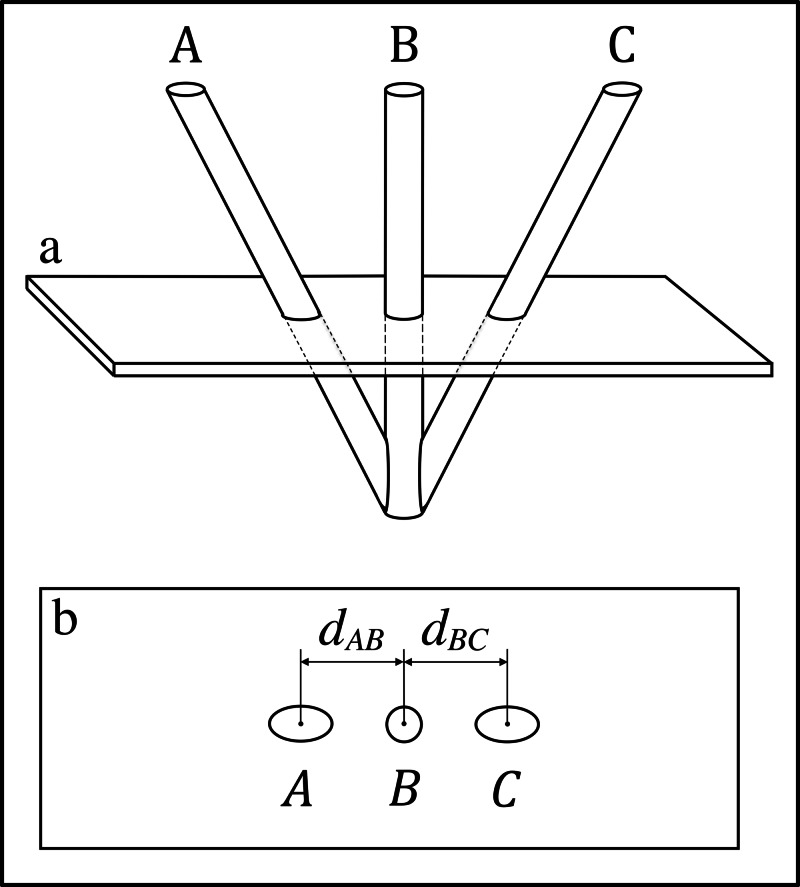

Figure 2 depicts the Sturm-Pastyr localizer that comprises two diagonal rods and one vertical rod. For the Sturm-Pastyr localizer, calculation of the  -coordinate of the point of intersection of the cylindrical axis of rod

-coordinate of the point of intersection of the cylindrical axis of rod  with the tomographic section is performed via the following non-linear equation that is derived in the Appendix [5].

with the tomographic section is performed via the following non-linear equation that is derived in the Appendix [5].

|

In this equation,  and

and  are distances measured in the

are distances measured in the  coordinate system of the medical image. At the bottom of rod

coordinate system of the medical image. At the bottom of rod  , i.e., at the apex of the V-shaped Sturm-Pastyr localizer,

, i.e., at the apex of the V-shaped Sturm-Pastyr localizer,  . When vertical rod

. When vertical rod  is perpendicular to the tomographic section, i.e., when the tomographic section is parallel to the base of the stereotactic frame, Equation (2) reduces to

is perpendicular to the tomographic section, i.e., when the tomographic section is parallel to the base of the stereotactic frame, Equation (2) reduces to

|

This equation applies because the Sturm-Pastyr localizer is manufactured such that the angle between rods  and

and  , and the angle between rods

, and the angle between rods  and

and  , are both

, are both  [6].

[6].

Figure 2. The Sturm-Pastyr Localizer and its Intersection with a Tomographic Section.

Side view of the Sturm-Pastyr localizer. A tomographic section intersects rods

Side view of the Sturm-Pastyr localizer. A tomographic section intersects rods  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.  Tomographic image. The intersection of the tomographic section with rods

Tomographic image. The intersection of the tomographic section with rods  ,

,  , and

, and  creates fiducial ellipses

creates fiducial ellipses  and

and  and fiducial circle

and fiducial circle  in the tomographic image. The distance

in the tomographic image. The distance  between the centers of ellipse

between the centers of ellipse  and circle

and circle  and the distance

and the distance  between the centers of circle

between the centers of circle  and ellipse

and ellipse  are used to calculate the

are used to calculate the  -coordinate of the point of intersection of the cylindrical axis of rod

-coordinate of the point of intersection of the cylindrical axis of rod  with the tomographic section [6].

with the tomographic section [6].

Equation (3) requires specification of the pixel size for the medical image to permit conversion of the distances  and

and  to millimeters. Equation (2) also requires specification of the pixel size because the units of

to millimeters. Equation (2) also requires specification of the pixel size because the units of  calculated by Equation (2) are the units of

calculated by Equation (2) are the units of  and

and  , as demonstrated by dimensional analysis of Equation (2). This requirement, which does not apply to the N-localizer, renders the Sturm-Pastyr localizer susceptible to error. An erroneous value of

, as demonstrated by dimensional analysis of Equation (2). This requirement, which does not apply to the N-localizer, renders the Sturm-Pastyr localizer susceptible to error. An erroneous value of  will be calculated via Equations (2, 3) if the pixel size is specified incorrectly via user input, or computed incorrectly from fiducials in the medical image [6], or recorded incorrectly in medical image metadata that require frequent calibration of the imaging system to guarantee correct pixel size.

will be calculated via Equations (2, 3) if the pixel size is specified incorrectly via user input, or computed incorrectly from fiducials in the medical image [6], or recorded incorrectly in medical image metadata that require frequent calibration of the imaging system to guarantee correct pixel size.

Figures 1, 2 demonstrate that the tomographic section of a medical image has a finite thickness. It is convenient to ignore this thickness and to approximate a tomographic section as an infinitely thin plane. This "central" plane lies midway between the top and bottom halves of the tomographic section, analogous to the way that a slice of cheese is sandwiched between two slices of bread. In the following presentation, the term "tomographic section" will be used as an abbreviation for the term "central plane of the tomographic section."

Similarly, it is convenient to ignore the diameter of rods  ,

,  , and

, and  in Figures 1, 2 and to approximate each rod as an infinitely thin cylindrical axis. In the following discussion, the term "rod" will be used as an abbreviation for the term "cylindrical axis of a rod." Hence, in the following presentation, the intersection of a "rod" with a "tomographic section" is equivalent to the intersection of a line with a plane and defines a point.

in Figures 1, 2 and to approximate each rod as an infinitely thin cylindrical axis. In the following discussion, the term "rod" will be used as an abbreviation for the term "cylindrical axis of a rod." Hence, in the following presentation, the intersection of a "rod" with a "tomographic section" is equivalent to the intersection of a line with a plane and defines a point.

Monte Carlo algorithm

The accuracies of the N-localizer and Sturm-Pastyr localizer are compared via Monte Carlo simulation that is performed using the following algorithm.

1. A  -coordinate is chosen to express the height above the base of the stereotactic frame, i.e., above the base of the localizer.

-coordinate is chosen to express the height above the base of the stereotactic frame, i.e., above the base of the localizer.

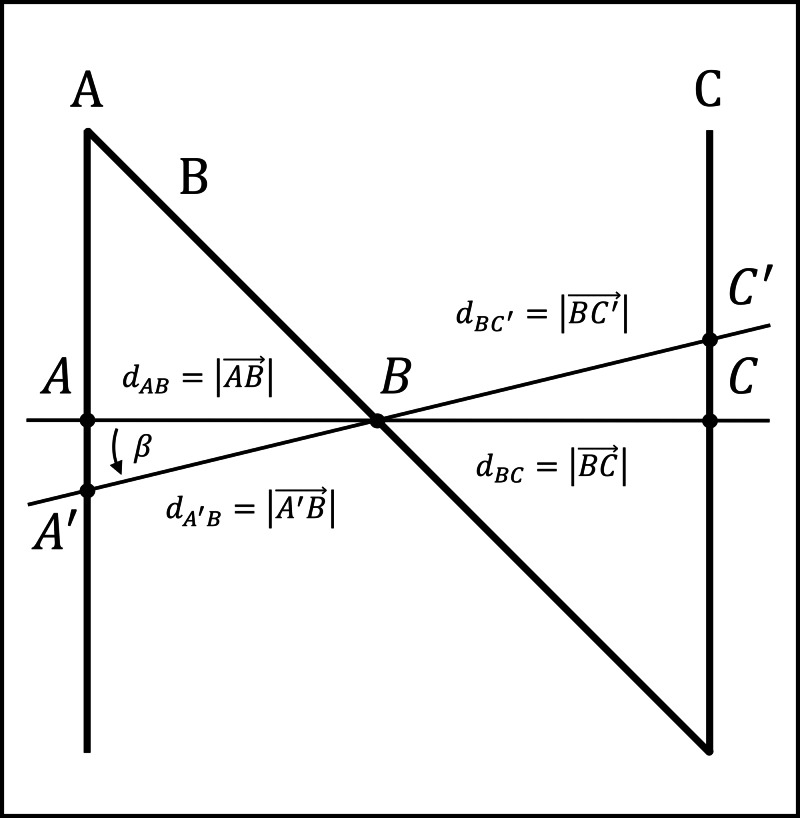

2. An angle  is chosen to express the angle by which the tomographic section is tilted with respect to the localizer such that line

is chosen to express the angle by which the tomographic section is tilted with respect to the localizer such that line  is tilted relative to the base of the stereotactic frame (see Figures 3, 7).

is tilted relative to the base of the stereotactic frame (see Figures 3, 7).

Figure 3. Depiction of the N-Localizer.

The N-localizer is depicted by rods  ,

,  , and

, and  that intersect a non-tilted tomographic section at fiducial points

that intersect a non-tilted tomographic section at fiducial points  ,

,  , and

, and  . The rods also intersect a tomographic section that is tilted by the angle

. The rods also intersect a tomographic section that is tilted by the angle  at fiducial points

at fiducial points  ,

,  , and

, and  . The distance between points

. The distance between points  and

and  is

is  . The distance between points

. The distance between points  and

and  is

is  .

.

3. The  pair is used to calculate the

pair is used to calculate the  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates of the fiducial points

coordinates of the fiducial points  ,

,  , and

, and  , respectively, in millimeters.

, respectively, in millimeters.

4. The  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates are perturbed via random numbers [7,8] in the range

coordinates are perturbed via random numbers [7,8] in the range  mm via

mm via  iterations to create

iterations to create  sets of perturbed

sets of perturbed  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates, where the superscript

coordinates, where the superscript  designates the

designates the  -th perturbed coordinate.

-th perturbed coordinate.

5. Each set of perturbed  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates is used to calculate a set of perturbed distances

coordinates is used to calculate a set of perturbed distances  ,

,  , and

, and  via the Pythagorean distance equation.

via the Pythagorean distance equation.

6. Each set of perturbed distances  ,

,  , and

, and  is used to calculate a perturbed

is used to calculate a perturbed  -coordinate.

-coordinate.

7. The  perturbed

perturbed  -coordinates are used to calculate the root mean square (RMS) error

-coordinates are used to calculate the root mean square (RMS) error  .

.

8. A new  pair is chosen and steps 3-7 are repeated.

pair is chosen and steps 3-7 are repeated.

Monte Carlo simulation for the N-localizer

Step 3 of the Monte Carlo algorithm requires calculation of the  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates for a

coordinates for a  pair. To promote clarity, the calculation for a

pair. To promote clarity, the calculation for a  pair, for which

pair, for which  , is discussed first.

, is discussed first.

Figure 3 depicts an N-localizer wherein rods  ,

,  , and

, and  intersect both a non-tilted tomographic section, for which

intersect both a non-tilted tomographic section, for which  , and a tilted tomographic section, for which

, and a tilted tomographic section, for which  . For the non-tilted section, calculation of the

. For the non-tilted section, calculation of the  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates of the respective fiducial points

coordinates of the respective fiducial points  ,

,  , and

, and  begins with calculation of the distances

begins with calculation of the distances  and

and  . The assumption that vertical rods

. The assumption that vertical rods  and

and  are separated by

are separated by  mm yields

mm yields  mm. The assumption that vertical rods

mm. The assumption that vertical rods  and

and  are

are  mm high yields

mm high yields  mm. Making the simplification that

mm. Making the simplification that  then yields

then yields  per Equation (1), where

per Equation (1), where  is specified in millimeters.

is specified in millimeters.

Given the distances  and

and  , it is possible to assign values to the

, it is possible to assign values to the  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates of the fiducial points

coordinates of the fiducial points  ,

,  , and

, and  . Making the simplification that the fiducial points lie along the

. Making the simplification that the fiducial points lie along the  -axis, a simple assignment is

-axis, a simple assignment is

|

For the tilted section, calculation of the  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates begins with calculation of the distances

coordinates begins with calculation of the distances  and

and  . Figure 3 reveals that triangles

. Figure 3 reveals that triangles  and

and  are both right triangles, thus

are both right triangles, thus

|

Hence, the  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates of the fiducial points

coordinates of the fiducial points  ,

,  , and

, and  are

are

|

Steps 4-7 of the Monte Carlo algorithm then proceed as follows. The  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates of the fiducial points

coordinates of the fiducial points  ,

,  , and

, and  are perturbed

are perturbed  times by random numbers to obtain

times by random numbers to obtain  perturbed

perturbed  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates, from which

coordinates, from which  perturbed distances

perturbed distances  and

and  are calculated, from which

are calculated, from which  perturbed

perturbed  -coordinates are calculated via Equation (1) and used to calculate the RMS error

-coordinates are calculated via Equation (1) and used to calculate the RMS error  . Then a new

. Then a new  pair is chosen and steps 3-7 of the Monte Carlo algorithm are repeated.

pair is chosen and steps 3-7 of the Monte Carlo algorithm are repeated.

Monte Carlo simulation for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer

For step 3 of the Monte Carlo algorithm applied to the Sturm-Pastyr localizer, calculation of the  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates for a

coordinates for a  pair begins with calculation of the distances

pair begins with calculation of the distances  and

and  . For this calculation, Equations (A1, A2) of the Appendix are solved for

. For this calculation, Equations (A1, A2) of the Appendix are solved for  and

and  to obtain

to obtain

|

In these equations,  for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer [6]. Hence,

for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer [6]. Hence,  and

and  are functions of only

are functions of only  and

and  .

.

Given the distances  and

and  , it is possible to assign values to the

, it is possible to assign values to the  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates of the fiducial points

coordinates of the fiducial points  ,

,  , and

, and  . Making the simplification that the fiducial points lie along the

. Making the simplification that the fiducial points lie along the  -axis, a simple assignment is

-axis, a simple assignment is

|

Steps 4-7 of the Monte Carlo algorithm then proceed as follows. The  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates of the fiducial points

coordinates of the fiducial points  ,

,  , and

, and  are perturbed

are perturbed  times by random numbers to obtain

times by random numbers to obtain  perturbed

perturbed  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates, from which

coordinates, from which  perturbed distances

perturbed distances  and

and  are calculated, from which

are calculated, from which  perturbed

perturbed  -coordinates are calculated via Equation (2) and used to calculate the RMS error

-coordinates are calculated via Equation (2) and used to calculate the RMS error  . Then a new

. Then a new  pair is chosen and steps 3-7 of the Monte Carlo algorithm are repeated.

pair is chosen and steps 3-7 of the Monte Carlo algorithm are repeated.

Discussion

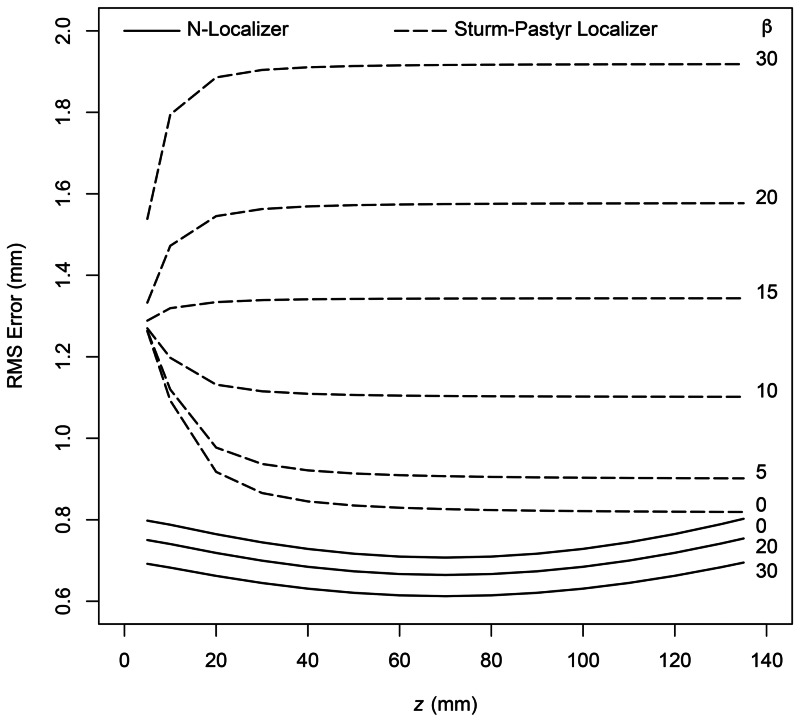

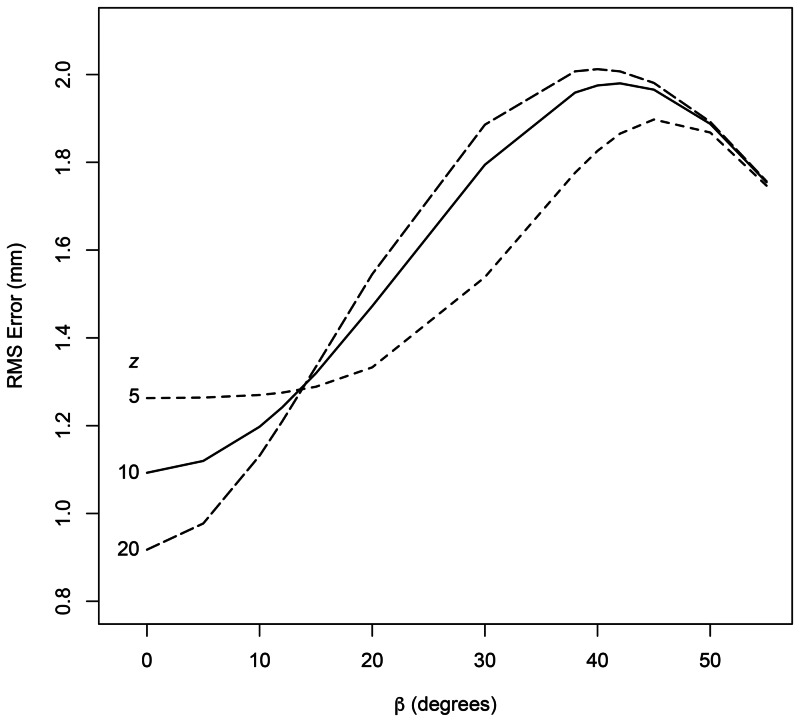

Figure 4 shows the results of Monte Carlo simulation for the N-localizer and the Sturm-Pastyr localizer. The RMS error in  for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer approaches the smaller RMS error for the N-localizer at only large values of

for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer approaches the smaller RMS error for the N-localizer at only large values of  and tilt angle

and tilt angle  . For all other values of

. For all other values of  and

and  , the Sturm-Pastyr localizer incurs significantly more RMS error than the N-localizer.

, the Sturm-Pastyr localizer incurs significantly more RMS error than the N-localizer.

Figure 4. RMS Error in  Plotted vs.

Plotted vs.  for the N-Localizer and Sturm-Pastyr Localizer.

for the N-Localizer and Sturm-Pastyr Localizer.

The RMS error in  is plotted vs.

is plotted vs.  for the N-localizer (solid curves) and the Sturm-Pastyr localizer (dashed curves). Each curve is generated using the value of

for the N-localizer (solid curves) and the Sturm-Pastyr localizer (dashed curves). Each curve is generated using the value of  that is specified in degrees to the right of the curve.

that is specified in degrees to the right of the curve.

RMS: root mean square

The RMS error for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer increases as  decreases and as

decreases and as  increases. These trends may be understood by inspecting Equation (7), which shows that

increases. These trends may be understood by inspecting Equation (7), which shows that  is directly proportional to

is directly proportional to  and inversely proportional to

and inversely proportional to  ; this sine term is maximized when

; this sine term is maximized when  degrees. These trends may also be understood by inspecting Figure 7, which shows that

degrees. These trends may also be understood by inspecting Figure 7, which shows that  is minimized for a given value of

is minimized for a given value of  when line segment

when line segment  is perpendicular to line segment

is perpendicular to line segment  , i.e., when

, i.e., when  . Thus, an increase in

. Thus, an increase in  in the range

in the range  degrees or a decrease in

degrees or a decrease in  decreases

decreases  and consequently, the random perturbations in the range

and consequently, the random perturbations in the range  mm become more significant relative to

mm become more significant relative to  and thereby increase the RMS error.

and thereby increase the RMS error.

Equation (7) also shows that  is inversely proportional to

is inversely proportional to  and hence increases monotonically as

and hence increases monotonically as  increases in the range

increases in the range  degrees, where

degrees, where  . And Equation (2) shows that

. And Equation (2) shows that  depends on

depends on  and

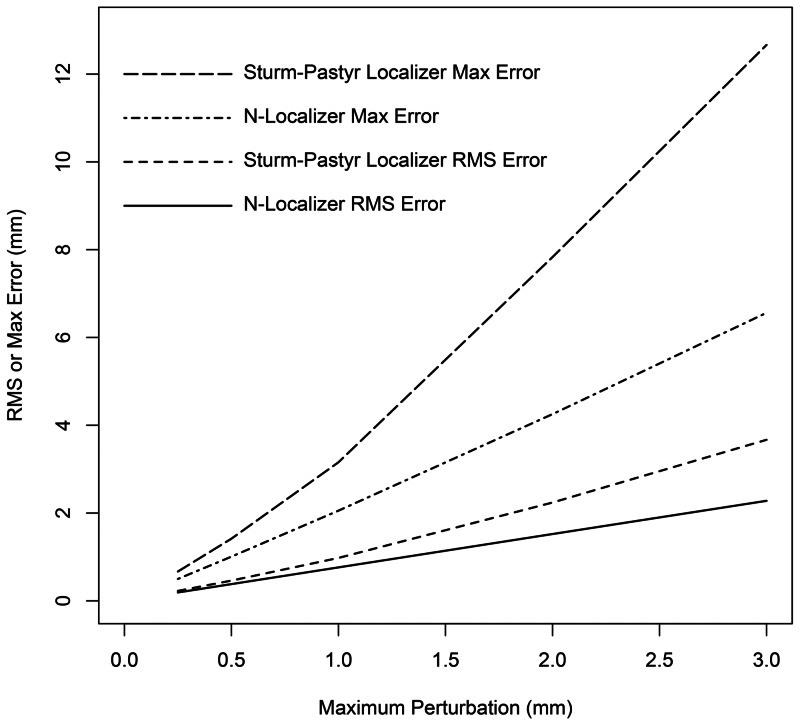

and  in a non-linear manner. Figure 5 demonstrates the effect of this non-linearity on the RMS error in

in a non-linear manner. Figure 5 demonstrates the effect of this non-linearity on the RMS error in  for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer and reveals that the maximum RMS error occurs near

for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer and reveals that the maximum RMS error occurs near  degrees.

degrees.

Figure 5. RMS Error in  Plotted vs.

Plotted vs.  for the Sturm-Pastyr Localizer.

for the Sturm-Pastyr Localizer.

The RMS error in  is plotted versus

is plotted versus  for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer. Each curve is generated using the value of

for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer. Each curve is generated using the value of  that is specified in millimeters to the left of the curve. The curves for

that is specified in millimeters to the left of the curve. The curves for  mm are similar to the curve for

mm are similar to the curve for  mm and are omitted.

mm and are omitted.

RMS: root mean square

The RMS error for the N-localizer decreases as  increases. This trend may be understood by inspecting Equation (6), which shows that the unperturbed

increases. This trend may be understood by inspecting Equation (6), which shows that the unperturbed  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates are inversely proportional to

coordinates are inversely proportional to  . Hence, as

. Hence, as  increases in the range

increases in the range  degrees, the unperturbed coordinates increase as well and in consequence, the random perturbations in the range

degrees, the unperturbed coordinates increase as well and in consequence, the random perturbations in the range  mm become less significant relative to the magnitudes of the unperturbed coordinates and thereby decrease the RMS error.

mm become less significant relative to the magnitudes of the unperturbed coordinates and thereby decrease the RMS error.

Random perturbations in the range  mm are used for the Monte Carlo algorithm due to the following considerations. A typical field of view (FOV) for a medical image that is used for planning stereotactic surgery lies in the range

mm are used for the Monte Carlo algorithm due to the following considerations. A typical field of view (FOV) for a medical image that is used for planning stereotactic surgery lies in the range  mm and comprises 512x512 pixels. Hence, the pixel size for such an image is in the range

mm and comprises 512x512 pixels. Hence, the pixel size for such an image is in the range  mm. A conservative estimate that the center of each fiducial circle or ellipse is displaced at most two pixels by random noise yields the perturbation range

mm. A conservative estimate that the center of each fiducial circle or ellipse is displaced at most two pixels by random noise yields the perturbation range  mm.

mm.

The effect of various perturbation ranges on the errors incurred by the N-localizer and Sturm-Pastyr localizer is shown in Figure 6. This figure plots the RMS and maximum errors for both localizers at  mm and

mm and  degrees vs. the maximum perturbation for the following continuous ranges of white noise:

degrees vs. the maximum perturbation for the following continuous ranges of white noise:  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  mm. The RMS and maximum errors for the N-localizer scale linearly with the maximum perturbation: the slope and correlation coefficient of a linear least-squares fit to the RMS-error data are 0.76 and 0.999991, respectively; the slope and correlation coefficient of a linear least-squares fit to the maximum-error data are 2.21 and 0.9998, respectively. As can be appreciated from Figure 6, the RMS and maximum errors for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer scale slightly super-linearly, as demonstrated by the slight upward concavity of the Sturm-Pastyr curves. The combination

mm. The RMS and maximum errors for the N-localizer scale linearly with the maximum perturbation: the slope and correlation coefficient of a linear least-squares fit to the RMS-error data are 0.76 and 0.999991, respectively; the slope and correlation coefficient of a linear least-squares fit to the maximum-error data are 2.21 and 0.9998, respectively. As can be appreciated from Figure 6, the RMS and maximum errors for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer scale slightly super-linearly, as demonstrated by the slight upward concavity of the Sturm-Pastyr curves. The combination  mm and

mm and  degrees pertains to a medical image that is obtained near the base of the stereotactic frame and almost parallel to the base of the frame. Such an image would be acquired for functional neurosurgery of the basal ganglia or for the insertion of deep brain stimulation implants.

degrees pertains to a medical image that is obtained near the base of the stereotactic frame and almost parallel to the base of the frame. Such an image would be acquired for functional neurosurgery of the basal ganglia or for the insertion of deep brain stimulation implants.

Figure 6. RMS and Maximum Errors vs. Maximum Perturbation for the N-Localizer and Sturm-Pastyr Localizer at  mm and

mm and  Degrees.

Degrees.

The RMS and maximum errors are plotted vs. the maximum perturbation for the N-localizer (solid and dot-dashed curves) and the Sturm-Pastyr localizer (dashed and long-dashed curves) at  mm and

mm and  degrees.

degrees.

RMS: root mean square

Conclusions

The Sturm-Pastyr localizer was originally intended for use with a medical image that is parallel to the base of the stereotactic frame, as depicted in Figure 2, wherein vertical rod  is perpendicular to the tomographic section. Obtaining such a parallel image is difficult because it requires precise alignment of the patient. The equations presented in the Appendix extend this localizer for use with a medical image that is not parallel to the base of the stereotactic frame. But these equations cannot surmount the V-shape of the Sturm-Pastyr localizer that hampers its accuracy for a non-parallel image. And, even for a parallel image, the accuracy of this localizer degrades substantially near the apex of the V, i.e., near the base of the stereotactic frame. This decreased accuracy may hinder the effectiveness of the Sturm-Pastyr localizer for targets deep in the brain, e.g., for functional neurosurgery of the basal ganglia or for insertion of deep brain stimulation implants.

is perpendicular to the tomographic section. Obtaining such a parallel image is difficult because it requires precise alignment of the patient. The equations presented in the Appendix extend this localizer for use with a medical image that is not parallel to the base of the stereotactic frame. But these equations cannot surmount the V-shape of the Sturm-Pastyr localizer that hampers its accuracy for a non-parallel image. And, even for a parallel image, the accuracy of this localizer degrades substantially near the apex of the V, i.e., near the base of the stereotactic frame. This decreased accuracy may hinder the effectiveness of the Sturm-Pastyr localizer for targets deep in the brain, e.g., for functional neurosurgery of the basal ganglia or for insertion of deep brain stimulation implants.

In contrast to the Sturm-Pastyr localizer, the N-localizer is intended for use with a medical image that is not perforce parallel to the base of the stereotactic frame. Hence, there is no requirement to precisely align the patient to obtain a parallel image. In fact, the accuracy of the N-localizer increases for a non-parallel image. And for either parallel or non-parallel images, the N-localizer is more accurate than the Sturm-Pastyr localizer. An additional advantage of the N-localizer compared to the Sturm-Pastyr localizer is that the N-localizer does not require specification of the pixel size for a medical image.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John A. Robinson for helpful comments.

Appendices

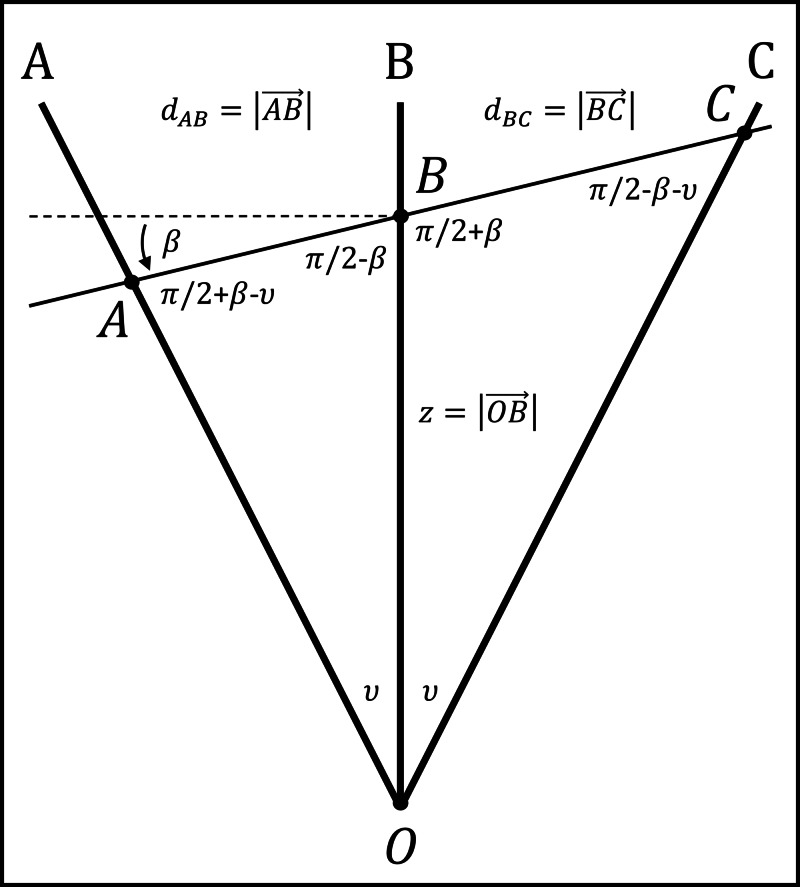

The Sturm-Pastyr localizer is designed to provide the  -coordinate when vertical rod

-coordinate when vertical rod  of the localizer is perpendicular to the tomographic section, i.e., when the tomographic section is parallel to the base of the stereotactic frame. This idealized case is depicted in Figure 2 but not in Figure 7. In the idealized case,

of the localizer is perpendicular to the tomographic section, i.e., when the tomographic section is parallel to the base of the stereotactic frame. This idealized case is depicted in Figure 2 but not in Figure 7. In the idealized case,  and

and  because angles

because angles  and

and  shown in Figure 7 are both

shown in Figure 7 are both  degrees [6]. However, achieving the idealized case is impractical due to the difficulty of precisely aligning the patient such that the tomographic section is perpendicular to vertical rod

degrees [6]. However, achieving the idealized case is impractical due to the difficulty of precisely aligning the patient such that the tomographic section is perpendicular to vertical rod  . Moreover, image noise perturbs the distances

. Moreover, image noise perturbs the distances  and

and  such that

such that  even if the patient is precisely aligned. For these reasons, Dai et al. have derived equations that permit calculation of

even if the patient is precisely aligned. For these reasons, Dai et al. have derived equations that permit calculation of  from

from  and

and  when the tomographic section is not perpendicular to vertical rod

when the tomographic section is not perpendicular to vertical rod  [6].

[6].

Figure 7. Depiction of the Sturm-Pastyr Localizer.

The Sturm-Pastyr localizer is depicted by rods  ,

,  , and

, and  that intersect the tomographic section at fiducial points

that intersect the tomographic section at fiducial points  ,

,  , and

, and  . The tomographic section is tilted by

. The tomographic section is tilted by  degrees. The distance between points

degrees. The distance between points  and

and  is

is  . The distance between points

. The distance between points  and

and  is

is  . The distance between points

. The distance between points  and

and  is

is  . Because angle

. Because angle  is a constant for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer, i.e.,

is a constant for the Sturm-Pastyr localizer, i.e.,  degrees [6], angles

degrees [6], angles  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are functions of only angle

are functions of only angle  , e.g., angle

, e.g., angle  .

.

Understanding the derivation of Dai, et al. requires familiarity with only trigonometry and algebra. However, because Dai, et al. omitted several intermediate steps from their derivation, it is unnecessarily obscure. The intermediate steps are provided below and in addition, the result reported by Dai, et al. is extended to yield an expression that contains no trigonometric functions.

The derivation of Dai, et al. produces an equation for the angle  in terms of the distances

in terms of the distances  and

and  as follows.

as follows.

Application of the law of sines to triangle  of Figure 7 yields

of Figure 7 yields

|

In this equation,  and

and  .

.

Similarly, application of the law of sines to triangle  yields

yields

|

In this equation,  and

and  .

.

Dividing Equation (A1) by Equation (A2) eliminates  and

and  to yield

to yield

|

Applying the rule for the sine of the sum of two angles followed by the rule for the cosine of the sum of two angles produces

|

Cross multiplication by the denominators and then factoring in  and

and  yields

yields

|

Substituting  into Equation (A5) yields

into Equation (A5) yields

|

Solving Equation (A6) for  completes the derivation of Dai, et al [6].

completes the derivation of Dai, et al [6].

|

Solving Equation (A1) for  yields

yields

|

Computing  via Equation (A7) and substituting

via Equation (A7) and substituting  into Equation (A8) calculates

into Equation (A8) calculates  in terms of

in terms of  and

and  when the tomographic section is not perpendicular to vertical rod

when the tomographic section is not perpendicular to vertical rod  .

.

An expression for  in terms

in terms  and

and  that does not involve trigonometric functions is obtained by first constructing expressions for

that does not involve trigonometric functions is obtained by first constructing expressions for  and

and  via inspection of Equation (A6)

via inspection of Equation (A6)

|

Applying the rules for the sine and cosine of the sum of two angles to Equation (A8) yields

|

Substituting  into Equation (A10) yields

into Equation (A10) yields

|

Substituting Equation (A9) into Equation (A11) yields a non-linear expression for  in terms

in terms  and

and  that does not involve trigonometric functions [5]

that does not involve trigonometric functions [5]

|

When  , Equation (A12) reduces to Equation (3).

, Equation (A12) reduces to Equation (3).

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.A computerized tomography-computer graphics approach to stereotaxic localization. Brown RA. J Neurosurg. 1979;50:715–720. doi: 10.3171/jns.1979.50.6.0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stereotactic computer tomography with a modified Riechert-Mundinger device as the basis for integrated stereotactic neuroradiological investigations. Sturm V, Pastyr O, Schlegel W, et al. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1983;68:11–17. doi: 10.1007/BF01406197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.A stereotactic head frame for use with CT body scanners. Brown RA. Invest Radiol. 1979;14:300–304. doi: 10.1097/00004424-197907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.A CT-based computerized treatment planning system for I-125 stereotactic brain implants. Weaver K, Smith V, Lewis JD, et al. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;18:445–454. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(90)90114-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alaminos-Bouza AL. Functional Neurosurgery. Vol. 1. São Paulo, Brazil: Alaúde Editorial Ltda.; 2014. Imaging, stereotactic space and targeting in functional neurosurgery; pp. 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- 6.An algorithm for stereotactic localization by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Dai J, Zhu Y, Qu H, Hu Y. Phys Med Biol. 2001;46:0. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/46/1/401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.RANLUX: A Fortran implementation of the high-quality pseudorandom number generator of Lüscher. James F. Comput Phys Commun. 1994;79:111–114. [Google Scholar]

- 8.A portable high-quality random number generator for lattice field theory simulations. Lüscher M. Comput Phys Commun. 1994;79:100–110. [Google Scholar]