Abstract

Alopecia has proven to be a persistent problem for captive macaques; many cases continue to elude explanations and effective treatments. Although almost all captive populations exhibit alopecia rates higher than those seen in the wild, there also appear to be wide ranges in rates reported across primate facilities. In this study we looked at alopecia ratings for rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) obtained from five primary suppliers and currently housed at the Washington National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC). There were significant differences in alopecia ratings based on prior facility, despite the fact that animals had left their prior facilities at least 10 months previously and 60% had left more than 2 years previously. Possible explanations for the facility effect may include longer than anticipated time lines for alopecia amelioration, early experience effects, and genetic contributions. Our results should provide a cautionary note for those evaluating alopecia, treatments for alopecia, and the current environments of alopecic animals. It is possible that not all alopecia is caused, or can be ameliorated, by changes in the immediate environment.

Keywords: environment, sex differences, hair regrowth, amelioration

INTRODUCTION

Alopecia is a consistent problem for captive primates. In rhesus macaques, rates of animals reported to display some extent of coat damage range from less than 30% [Beisner & Isbell, 2008; Kramer et al., 2010] to 70% and higher [Bellanca et al., 2014; Lutz et al., 2013; Steinmetz et al., 2006]. Although multiple etiologies have been identified, none appear to account for the large percentages of affected animals that are typical in laboratory colonies. Two recent studies investigating physiological differences between alopecic and normally haired animals were unable to find any physiological markers that might explain alopecia in large numbers of animals [Luchins et al., 2011; Steinmetz et al., 2005]. Given the general absence of physiological abnormalities, stress or behavioral factors (e.g., hair pulling) have often been implicated [Beisner & Isbell, 2008; Honess et al., 2005]. Although hair pulling has been documented as a factor in alopecia, several studies with careful observation of hair pulling behavior conclude that this behavior still accounts for only a small percentage of all alopecia cases [Luchins et al., 2011; Lutz et al., 2013]. The lack of histological differences between alopecic and normally haired animals as documented by Steinmetz et al. [2005] also fails to indicate a primary role of hair pulling in alopecia presentation. Stress has been postulated to influence alopecia through a disruption of the hair growth cycle (telogen effluvium), but direct evidence is lacking [Novak & Meyer, 2009; Orion & Wolf, 2013; Picardi & Abeni, 2001]. Further, reported associations between cortisol (a commonly used biological marker of stress) and alopecia have been conflicting. One study found reduced fecal cortisol levels [Steinmetz et al., 2006], one found increased serum cortisol levels (although it is important to note that levels for both groups were within normal reference ranges) [Luchins et al., 2011], and a third found no association in serum cortisol levels [Kramer et al., 2010].

In at least some nonhuman primate species, alopecia rates vary seasonally, with the poorest coat conditions observed in the spring and best coat conditions observed in the fall [Steinmetz et al., 2006]. This variation has been documented for rhesus macaques and may also depend on breeding status [Vessey & Morrison, 1970]. It is unclear to what extent seasonality may continue to influence animals housed partially or entirely indoors, but the Steinmetz et al. [2006] study is notable in that it included animals housed entirely indoors, entirely outdoors, and in mixed indoor/outdoor housing and reported observing seasonal fluctuation in all groups. Additionally, Kroeker et al. [2014] found evidence of seasonal variation in animals housed entirely indoors.

To our knowledge, the wide range among facilities in reported alopecia rates in captive primates has not been commented on previously. This variation can be partially explained by differences in reporting practices, housing situations and husbandry practices. However a multi-site survey which utilized standardized reporting practices of uniformly housed rhesus macaques still found variability in alopecia rates, ranging from 34% to 86% [Lutz et al., 2013].

A natural inclination is to treat the variation due to facility differences as noise that must be statistically controlled or overcome in order to detect the influence of other systematic variables. However, exploring inter-facility differences may be a fruitful direction that could further illuminate influences on alopecia. Surveying alopecia across multiple sites can present obvious logistical difficulties. However, inter-facility differences may also be explored by examining animals in one location that have been previously obtained elsewhere.

The Washington National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC) obtains almost all rhesus monkeys from other suppliers rather than breeding on site. It is therefore possible to evaluate the effects of prior facility on alopecia at a later time. As part of our ongoing inquiry into assessment and treatment of alopecia, we hypothesized that an animal’s prior facility might have an influence on their alopecia status even after animals had left that facility. Further, we investigated whether this effect continued beyond a time period which would be sufficient for hair regrowth. If alopecia continues to vary systematically by prior facility, even after animals have been removed from those environments, then this shows that although immediate environmental effects may still be important, other more distal sources of systematic variation remain.

METHODS

Animals were maintained in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [National Research Council, 2011], participated in the WaNPRC Environmental Enhancement plan and were fed a nutritionally balanced diet, supplemented at least three times per week with additional fruit and vegetables. The WaNPRC is accredited by AAALAC (Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care) International and all research was conducted under protocols approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). The research adhered to the American Society of Primatologists Principles for the Ethical Treatment of Nonhuman Primates.

Subjects

The sample included 225 (101 males, 124 females) rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) at the WaNPRC who were observed in at least one quarterly observation between September 2011 and March 2014 as part of our standard laboratory procedure, who were at least 4 years of age at the time of observation, who had no history of pregnancy in our facility, and who came to the WaNPRC from one of five primary suppliers.

Housing Facilities

All animals were housed indoors on a 12-hr light cycle. Most subjects were housed in two-tiered stainless steel cages with 1.32 or 1.83 m2 floor space and 76.2 or 81.28 cm height, complying with Animal Welfare Act USDA standards for NHPs based on animal weight. Heavier subjects were housed in single-tier cages with 2.44 m2 floor space and 91.44 cm height. All cages were equipped with perches. All cages had sides comprised of half mesh and half solid panels to provide opportunities for privacy as well as for visual contact with conspecifics in the room. From our sample, 33 (14.7%) animals were housed socially for a majority (at least 75%) of observations, an additional 18 (8%) animals were housed in protected contact with access to a social partner through wide-spaced “grooming-contact” bars for a majority of observations, and 115 (51.1%) animals were housed in single cages for a majority of observations. The remaining 59 (26.2%) animals were observed in a mix of social and single housing during observations for this study with six of these (3% of total sample) having a combination of social and protected contact housing for at least 75% of observations.

Sampling

Alopecia severity scores were recorded in conjunction with standard WaNPRC quarterly observations. Quarterly observations and procedures for alopecia scoring have been described elsewhere [Bellanca et al., 2014; Kroeker et al., 2014]. Briefly, the monitoring consisted of 10-min observations of animals in their home cages. At the end of the 10-min observation, the observed animals were rated on an alopecia severity scale ranging from 0 to 4, which described the extent of alopecia for an animal quantified by number of affected body parts (0 = 0 affected body parts; 1 = 1–2 affected body parts; 2=3–5 affected body parts; 3=6–8 affected body parts; and 4=9 or more affected body parts). In all, 11 body parts, each accounting for approximately 9% of the total body area were considered. These included the head, arms, upper and lower legs, chest, abdomen, and upper and lower back. The tail comprises the final 1% of body area. Since the tail accounts for such a small percentage of total body area, the condition of the tail is noted but does not influence the final score assignment. Personnel involved in scoring the animals used for this study had inter-observer reliability scores ranging from 0.88 to 0.96 (determined by Cohen’s kappa). Cohen’s kappa can be conceptualized as the proportion of agreement between two raters after agreement due to chance has been excluded. As a measure of reliability, it is preferable to a simple percentage agreement as percentage agreement may be artificially inflated due to chance agreements. A total of 1,102 observations from these animals were used in the analysis. Animals had between 1 and 11 observations each .

Identification of Hair Pulling

Animals who hair pulled or had hair pulled by a social partner were identified at either the time of quarterly observations described above, or by WaNPRC personnel, including veterinary, behavioral, animal care, and research staff during daily monitoring. All WaNPRC personnel are trained in the identification of abnormal behaviors, which includes hair pulling. These animals are referred to behavioral staff.

Data Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS®, version 19 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and Stata®, version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Two sets of analyses using different data were conducted. The first (full sample) used all observations from all animals and the second (reduced sample) used only observations from animals that had been at the WaNPRC facility in Seattle for 10 months or longer. A criterion of 10 months was chosen as a time frame long enough to allow for potential hair regrowth in the event that animals might have come to us with alopecia, while still being short enough to allow us to maintain the maximum number of animals in our sample. Thus, this sample allows us to eliminate observations of animals whose alopecia may have been due to immediate environmental influences at another facility. For all statistical tests, a P-value equal to or less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All t-tests and non-parametric two sample tests were performed as two-tailed tests. The percentage of total observations receiving each alopecia rating was computed. For each animal, the percentage of time in social housing was calculated by dividing the animal’s number of observations conducted while the animal was in social housing by the animal’s total number of observations. Differences in percentage oftime in social housing between high alopecia (scores of 3 or 4) and low alopecia (scores of 0–2) groups were explored by t-test.

Analysis of facility differences

For each animal, means for age and length of time at WaNPRC were computed across all observations for that animal. Differences in these individual means across facility were then investigated by one-way ANOVAs. Post hoc two-tailed tests using Bonferroni probabilities were computed for significant omnibus results. Differences in sex distributions across facilities were investigated by chi square.

To investigate the influence of prior facility on current alopecia score, we used a generalized ordered logistic regression (available in Stata using the “gologit2” program). This model was chosen to accommodate our ordinal dependent variable (alopecia score). Prior facility, sex, animal age and length of time in the current facility were entered as predictors. Because most monkeys had repeated observations, animal ID was entered as a random effect. An ordered logistic regression expresses the odds that a response will be above or below a given level, often called a threshold. Because the number of observations with a “4” alopecia score was low, we combined the “3” and “4” scores into one category in our analysis. Our ordered regression then had 3 thresholds representing the probability that the value of a specific alopecia score would be: 0 versus ≥1, ≤1 versus ≥2, and ≤2 versus 3. A simplifying assumption of the ordered logistic regression is that the odds of achieving each threshold are proportionate at a given level of the independent variable. The proportional odds assumption can be assessed with the “autofit” option in the “gologit2” program. For independent variables where this assumption is not met, separate parameter estimates can be allowed at each threshold [Williams, 2006]. For independent variables meeting the proportional odds assumption, the odds ratio is constrained to be the same at all thresholds. This partial proportional odds model provides a compromise between a full proportional odds model whose assumptions are often violated, and a completely non-ordered model (e.g., multinomial logistic regression) which may return more parameters than are necessary.

Analysis of changes in alopecia

In order to examine possible changes in alopecia scores occurring shortly after arrival at WaNPRC we identified a group of animals with alopecia scores available within 2 months of arrival. These scores were compared with later scores from the same animals using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. The relationship between the first and later scores was described using a Spearman rank order correlation. We also examined systematic differences in the initial alopecia scores animals received at WaNPRC based on how long they had been at our facility at the time of the assessment, whether short (up to 3 months) medium (3 months to 3 years) or long (3–5.5 years) amounts of time. Differences among alopecia scores of these three groups were examined with the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Analysis of hair pulling and alopecia

Chi square analyses were conducted to investigate the relationship between hair pulling behavior and alopecia score, and between hair pulling behavior and facility of origin. Differences between hair pullers and other animals in age and time at WaNPRC were investigated with independent t-tests.

RESULTS

All Animals (N = 225)

Sample sizes and means for animal age and length of time at WaNPRC are given in Table I by prior facility and sex. Animals ranged in age from 4 to 20.7 years and had been at WaNPRC between 0.04 and 16.5 years . Animals received a rating of “0” (no alopecia) on 43% of observations, and ratings of “1” on 32%, “2” on 19%, “3” on 6%, and “4” on 1% of observations. For animals receiving a “4”, clinical notes from routine semi-annual physical exams which were performed closest in time to the alopecia scoring were reviewed. Alopecia was most often noted to be “patchy” and most frequently noted to be occurring on the legs and arms, although also noted on the shoulders, back, and tail. There were no obvious patterns noted that would indicate friction alopecia from caging. With the exception of one animal with erythema, there were no noted skin conditions. One animal was noted to be underweight on one exam but later regained weight. Of the 1,102 observations, 22% were conducted for animals in social housing. Animals with the most severe alopecia (scores of 3 or 4) were in social housing an average of 24% of their observations, which was not significantly different from animals with less severe alopecia who were in social housing an average of 19% of observations (t = 0.93, df = 223, P = 0.36).

TABLE I.

Sample Sizes (N) and Means for Animal Age and Length of Time at Washington National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC) By Prior Facility and Sex for Animals at WaNPRC More Than 10 Monthsa

| Facility | N | Animal age (years) | SD | Length of time at WaNPRC (years) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | |||||

| Male | 5 (5) | 6.1 (6.0) | 1.1 (1.2) | 3.1 (3.1) | 1.3 (1.4) |

| Female | 28 (28) | 5.3 (4.9) | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.6) | 0.1 (0.1) |

| Total | 33 (33) | 5.4 (5.1) | 0.8 (0.8) | 1.2 (1.0) | 0.9 (1.0) |

| B | |||||

| Male | 29 (40) | 6.4 (6.2) | 4.1 (3.5) | 3.0 (2.2) | 3.9 (3.5) |

| Female | 13 (15) | 8.0 (7.7) | 3.2 (3.1) | 2.7 (2.3) | 1.6 (1.8) |

| Total | 42 (55) | 6.9 (6.6) | 3.9 (3.4) | 2.9 (2.2) | 3.3 (3.1) |

| C | |||||

| Male | 5 (14) | 8.3 (10.5) | 2.3 (2.4) | 4.3 (1.8) | 2.0 (2.2) |

| Female | 11 (15) | 6.2 (6.7) | 1.0 (1.6) | 3.5 (2.7) | 0.5 (1.4) |

| Total | 16 (29) | 6.9 (8.5) | 1.8 (2.8) | 3.7 (2.3) | 1.2 (1.9) |

| D | |||||

| Male | 12 (20) | 5.9 (5.5) | 0.6 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.4) |

| Female | 66 (66) | 12.7 (12.7) | 1.7 (1.7) | 5.6 (5.6) | 0.2 (0.2) |

| Total | 78 (86) | 11.6 (11.0) | 2.9 (3.4) | 4.9 (4.5) | 1.6 (2.1) |

| E | |||||

| Male | 19 (22) | 6.9 (6.8) | 2.3 (1.9) | 2.3 (1.9) | 1.0 (1.2) |

| Female | 0 | — | — | — | — |

| Total | 19 (22) | 6.9 (6.8) | 2.3 (1.9) | 2.3 (1.9) | 1.0 (1.2) |

Values in parentheses are for all animals.

Facility differences

There were significant differences among facilities for animal age (ANOVA: F = 33.1, df = 4,220, P < 0.001). Animals from Facility D were significantly older than animals from all other facilities (A vs. D: t = 9.7, df = 59.5, P < 0.001; B vs. D: t = 8.5, df = 70.5, P < 0.001; C vs. D: t = 3.8, df = 58.5, P < 0.005; E vs. D: t = 5.9, df = 54, P < 0.001) and animals from Facility C were significantly older than animals from Facility A (t = 4.6, df = 31, P < 0.001). There were significant differences among facilities for animals’ length of time at WaNPRC (ANOVA: F = 19.9, df = 4,220, P < 0.001). Animals from Facility D had longer times at WaNPRC than animals from all other facilities (A vs. D: t = 7.7, df = 59.5, P < 0.001; B vs. D: t = 5.8, df = 70.5, P < 0.001; C vs. D: t = 4.6, df = 58.5, P < 0.001; E vs. D: t = 4.8, df = 54, P < 0.001). There were significant differences among the facilities in the sex distribution (χ2 = 72.4, df = 4, P < 0.001) with facilities A and D having fewer males than would be expected by chance.

Coefficients, odds ratios, and associated P values for the generalized ordered logistic regression examining the effects of prior facility on alopecia are given in Table II. Assumptions of proportional odds were not met for Facility A. Thus, separate coefficients for the different thresholds of alopecia were estimated for Facility A, but held constant for all other predictors. Sex was significantly related to alopecia score, with females being 1.6 times more likely than males to have a higher score. There were also significant effects for facility of origin. Animals from Facility A differed from all other facilities at the lowest threshold (i.e., the probability of having a 0 score vs. a score higher than 0). Animals from all other facilities were significantly less likely to have a score higher than 0 than were animals from Facility A (Odds ratios: 0.20–0.45). There were no differences between Facility A animals and other facilities at higher thresholds. Additionally, animals from Facility B were less likely to have higher alopecia ratings than animals from Facility D (Odds ratio = 0.46). Animal age and time at WaNPRC were not significant.

TABLE II.

Ordered Logistic Regression Results Examining Effects of Prior Facility on Alopecia

| All animals (full sample) |

Animals at Seattle longer than 10 months (reduced sample) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta coefficient | Odds ratioa | P | Beta coefficient | Odds ratio | P | |

| Sex | 0.483 | 1.62 | <0.05 | 0.767 | 2.13 | <0.01 |

| Facility | ||||||

| A vs. B | −0.751 | 0.47 | <0.05 | |||

| Threshold 0 | −0.808 | 0.45 | <0.05 | |||

| Threshold 1 | 0.089 | 1.09 | 0.79 | |||

| Threshold 2 | −0.031 | 0.97 | 0.95 | |||

| A vs. C | −1.391 | 0.25 | <0.005 | |||

| Threshold 0 | −1.16 | 0.31 | <0.01 | |||

| Threshold 1 | −0.266 | 0.77 | 0.54 | |||

| Threshold 2 | −0.386 | 0.70 | 0.48 | −1.567 | 0.21 | <0.001 |

| A vs. D | ||||||

| Threshold 0 | −1.59 | 0.20 | <0.001 | |||

| Threshold 1 | −0.693 | 0.50 | 0.06 | |||

| Threshold 2 | −0.813 | 0.44 | 0.10 | |||

| A vs. E | −1.132 | 0.32 | <0.05 | |||

| Threshold 0 | −1.479 | 0.23 | <0.005 | |||

| Threshold 1 | 0.582 | 1.79 | 0.20 | |||

| Threshold 2 | 0.702 | 2.02 | 0.21 | |||

| B vs. C | −0.355 | 0.701 | 0.33 | −0.640 | 0.53 | 0.14 |

| B vs. D | −0.781 | 0.46 | <0.01 | −0.816 | 0.44 | 0.05 |

| B vs. E | −0.671 | 0.51 | 0.06 | −0.381 | 0.68 | 0.39 |

| C vs. D | −0.427 | 0.65 | 0.22 | −0.176 | 0.84 | 0.76 |

| C vs. E | −0.316 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.258 | 1.29 | 0.66 |

| D vs. E | 0.111 | 1.12 | 0.78 | 0.434 | 1.54 | 0.37 |

| Age (years) | 0.051 | 1.05 | 0.37 | −0.012 | 0.99 | 0.91 |

| Time at WaNPRCb | −0.103 | 0.90 | 0.13 | −0.021 | 0.98 | 0.87 |

Odds ratio = ebeta. Inversely, beta = loge (odds ratio).

Washington National Primate Research Center.

Animals at WaNPRC 10 Months or Longer (N = 188)

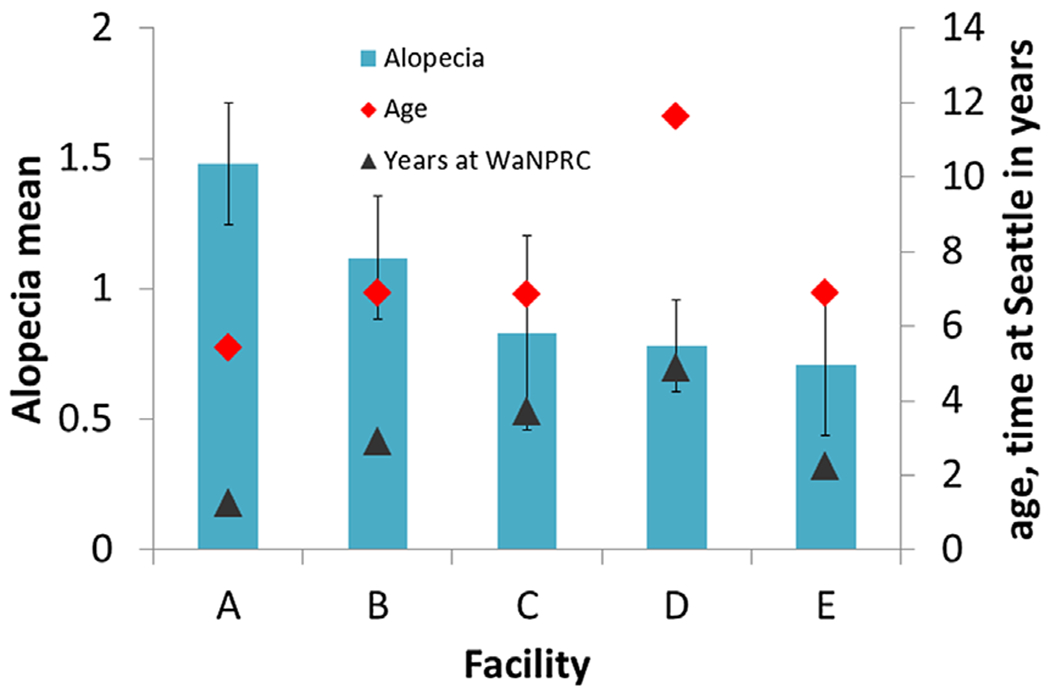

Animals ranged in age from 4 to 20.7 years and had been at WaNPRC between 0.85 and 16.5 years . Animal age differed significantly by prior facility (ANOVA: F = 41.4, df = 4,183, P < 0.001). Animals from Facility D were significantly older than animals from all other facilities (A vs. D: t = 10.8, df = 55.5, P < 0.001; B vs. D: t = 8.9, df = 60, P < 0.001; C vs. D: t = 6.3, df = 47, P < 0.005; E vs. D: t = 6.7, df = 48.5, P < 0.001). Time at WaNPRC differed significantly by prior facility (ANOVA: F = 23.4, df = 4,183, P < 0.001). Animals from Facility D had been at WaNPRC longer than animals from Facilities A (t = 8.9, df = 55.5, P < 0.001), B (t = 5.3, df = 60, P < 0.001), and E (t = 5.2, df = 48.5, P < 0.001) and animals from Facilities B (t = 3.6, df = 37.5, P < 0.005) and C (t = 4.1, df = 24.5, P = 0.001) had longer times than Facility A. There were significant differences for sex distribution among the facilities (χ2 = 73.3, df = 4, P < 0.001) with facilities A and D having fewer males than would be expected by chance. Means for age, time at WaNPRC, and alopecia score by prior facility are presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Mean alopecia scores, ages, and length of time at Washington National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC) for animals at WaNPRC longer than 10 months. Error bars are standard errors. The letters A through E designate the five prior facilities of animals currently at WaNPRC. Alopecia is scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 4, quantified by number of affected body parts (0=0 affected body parts; 1=1–2 affected body parts; 2=3–5 affected body parts; 3=6–8 affected body parts; and 4=9 or more affect body parts).

Assumptions for proportional odds were met for all independent variables in this model. Thus, the effect of each independent variable is captured by one parameter which describes the effect at all thresholds of alopecia score. Sex was significantly related to alopecia score, with females being 2.1 times more likely than males to have a higher score. Facility of origin effects were similar to those in the full sample analysis. Compared with Facility A, animals from all other facilities had a decreased likelihood of receiving higher alopecia scores (Odds ratios: 0.21–0.47), and animals from Facility D were less likely than animals from Facility B to have increased scores (Odds ratio = 0.44). Animal age and animal time at WaNPRC were not significant contributors to the model.

Analysis of Changes in Alopecia After Transfer to WaNPRC

The time animals spent at WaNPRC was not a significant contributor to the model in either the full or reduced samples. However, since we might suspect this variable to have a disproportionate effect on alopecia soonest after a move, we chose to investigate this variable further. Our full sample included 38 animals that were assessed within 2 months oftheir arrival at WaNPRC. Of these, 36 had at least one later alopecia score. For these 36 animals, initial scores were taken within 7–54 days of arrival and later scores were taken 69–116 days later . Initial and later scores were correlated rs = 0.3 which was just short of statistically significant (P = 0.06). For these 36 animals there was no significant difference between the initial and later scores (Wilcoxon signed rank test: Z = −0.613, N = 36, P = 0.54, two-tailed).

In a second analysis we investigated differences in animals’ initial alopecia scores depending on the length of time animals had been at WaNPRC. Animals were divided into three groups depending on how long they had been at WaNPRC when the initial score was recorded, either short (7 days to 3 months, N = 68), moderate (3 months to 3 years, N = 79) or longer (3 to 5.5 years, N = 76) amounts of time. Two animals who had been at WaNPRC for more than 15 years were not included. There was no significant difference in alopecia levels among these three groups (Kruskal–Wallis test: χ2 = 3.9, df = 2, P = 0.14).

Hair Pulling and Alopecia

A total of 56 (25%) animals in our full sample were observed to either pull their own hair (N = 46), have their hair pulled by a social partner (N = 6), or both (N = 4). Whether an animal was ever observed to hair pull or have their hair pulled by a partner was significantly related to their maximum alopecia score in both the full (χ2 = 37.9, df = 4, P < 0.001) and reduced samples (χ2 = 33.0, df = 4, P < 0.001), with animals showing more extensive alopecia more likely to exhibit hair pulling. In the full sample, 20 out of 38 animals (53%) with a maximum score of 3 or 4 were identified hair pullers, and in the reduced sample, 19 out of 31 animals (61%) with these scores were identified hair pullers. Incidence of hair pulling did not differ significantly by facility in the full sample (χ2 = 5.9, df = 4, P = 0.20), but did in the reduced sample (χ2 = 10.48.3, df = 4, P = 0.03), with facilities B and C having higher numbers of animals that hair pulled than would be expected by chance. Animals identified with hair pulling behavior had spent more time at WaNPRC (t = 2.1, df = 223, P < 0.05), but there was no significant difference in age between these groups (t = 0.30, df = 223, P = 0.76).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we present analyses with two samples. In the first (full) sample, we found that alopecia levels differed significantly based on prior facility. However, because some of the animals in this sample had been at WaNPRC for only short periods of time, it was not clear if differences were due to animals coming to our facility with varying levels of alopecia, or whether differences were due to alopecia developed here. In the second (reduced) sample including only animals at WaNPRC for 10 months or longer, we continued to see differences in alopecia levels based on prior facility. We argue that the results from these animals, who have been at WaNRPC longer, make a stronger argument for the sustained importance of previous environmental influences on alopecia. Sex distribution was unequal among the facilities and because sex has been shown in previous studies to influence alopecia, we included it as a factor in the analysis of facility differences. In our results, sex and prior facility both showed separate contributions to alopecia levels. Due to the limitations of our data collection, it is impossible to completely separate alopecia that may have begun at a prior facility from alopecia initially developed at WaNPRC. However, our analysis of a subsample of animals that had alopecia ratings shortly after their arrival at WaNPRC would seem to indicate that levels do not show significant patterns of change (either worsening or improving) correlated with time at our facility.

While the WaNPRC now has a policy requiring clinical workups for animals with alopecia scores of 4, workups were not required at the time these data were collected. However, retrospective review of contemporary veterinary records revealed that there were few obvious medical conditions or skin abnormalities that would explain the alopecia for the most severe alopecia cases. In routine physical exams the pattern of alopecia noted for the most severe cases was generally described as patchy and most commonly reported on the legs and arms.

Animals in our study were in social housing for 22% percent of the observations. An additional 17% of observations were conducted on animals in protected “grooming-contact.” The percentage of observations in social housing was slightly (but not significantly) higher for animals with the most severe alopecia ratings. Pulling one’s own hair, or having hair pulled by a social partner was found to be strongly related to alopecia in our sample. Despite this, 18 out of 38 animals in the full sample and 12 out of 31 animals in the reduced sample with the most severe alopecia scores did not exhibit hair pulling. These results are in line with those from other reports which show that though hair pulling is an important influence in alopecia, it does not explain all alopecic cases [Luchins et al., 2011; Lutz et al., 2013; Steinmetz et al., 2005]. In this study hair pulling was identified primarily by WaNPRC personnel who were working with and observing the animals. Animals in our facility are observed on a daily basis, often by multiple personnel. In addition to in-person observations, animals who are suspected of hair pulling or other concerning behaviors can be observed via live video feed, allowing us to capture behaviors that may not occur in the presence of human observers. Despite these measures, there remains some probability that some animals who pulled hair may have been missed. We believe this probability is small due to the high numbers of animals that were identified, and the high levels of monitoring animals receive.

The likelihood of being identified as a hair puller or having hair pulled by a social partner was not related to prior facility in the full sample but was in the reduced sample. Despite this relation, it does not appear that hair pulling plays a role in mediating the differences in alopecia seen across facilities, since the facilities with the highest rates of hair pulling are different from those with the highest levels of alopecia. Time for hair regrowth in rhesus macaques has been anecdotally reported to be between 6 weeks to 2 months [Novak et al., 2014; Novak & Meyer, 2009]. O’Neill-Wagner [1997] also reported regrowth within 2 months in adult rhesus following shaving or dye marking, although the timing for initiation of regrowth was often affected by season and breeding status. We chose 10 months as a criterion for inclusion in the reduced sample to allow adequate time for hair regrowth in the event that animals might have arrived with alopecia. Therefore, it seems unlikely that the persistent differences in alopecia seen after at least 10 months at WaNPRC can be explained by immediate factors in prior facilities that may have resulted in hair loss without opportunity for regrowth. Additionally, it should be noted that even though the criterion amount of time at our facility for inclusion in the “reduced sample” analysis was 10 months, most animals had been here much longer (60% over 2 years and nearly 40% over 5 years).

Our results indicate that when considering influences on alopecia, causes outside ofthe immediate environment deserve more consideration. Although we don’t know the exact mechanisms which might be responsible, three broad possibilities, offering areas for further research, present themselves. First, alopecia affected by immediate environmental variables may take longer to ameliorate than previously thought. In this potential scenario, animals would have arrived at our facility with alopecia that did not ameliorate. To our knowledge, the timing for reversal of alopecia through a change in environmental conditions has not been studied or reported on. The anecdote supplied in Novak et al. [2014] however, would argue against a long time table for amelioration of alopecia. In this example, a female monkey with alopecia apparently induced by a 7-week separation from her social partner had regained all her hair by 6 weeks after the reunion, seemingly indicating that hair regrowth began almost immediately following the removal of the activating condition. Davis & Suomi [2006] also note that rhesus females who lose hair during pregnancy begin re-growth immediately following parturition. It still may be the case that alopecia produced under more chronic conditions takes longer to ameliorate.

A second possibility is that alopecia may be affected, even into adulthood, by aspects of the early rearing environment. In this potential scenario a lifetime propensity toward alopecia may be set during a critical period early in development. Two recent studies have documented increased incidence of alopecia in rhesus adults related to early experience. In the first, alopecia was found to be more prevalent in peer-reared female rhesus when compared to both mother-raised rhesus and rhesus raised in individual cages with surrogates and limited access to peers [Conti et al., 2012]. This effect was not found for males. In the second, an increased incidence of alopecia was found for rhesus with a history of continuous indoor housing when compared with rhesus previously housed outdoors, even though all animals were housed indoors at the time of the study [Kramer et al., 2010]. How these early conditions influence alopecia is not clear, although the authors have suggested, in line with the hygiene hypothesis, that early outdoor rearing might increase pathogen exposure which is necessary for immune development. Animals in the current study arrived at WaNPRC between 1.1 and 15 years of age, which would generally be considered to be after this critical period of development [Rommeck et al., 2009; Conti et al., 2012]. Although we do not have access to the information on early rearing for animals in our study, it seems reasonable to assume that they may have experienced different early rearing environments (e.g., outdoor vs. indoor housing, social vs. single) that varied somewhat systematically across facilities. If so, these differences in early rearing may have continued to influence alopecia in our adult animals.

A third possibility is that a propensity toward alopecia is genetically heritable. Since a higher degree of relatedness would be expected among animals from the same facility than animals from different facilities, this relatedness could explain the increased similarity in alopecia scores. Although alopecia almost certainly has multiple etiologies, genetic heritability has been established for the autoimmune condition alopecia areata, which is a common etiology for alopecia in humans [Jackow et al., 1998; Xiao et al., 2006; Coda et al., 2010]. With the exception of one case report [Beardi et al., 2007], alopecia areata has not been described in rhesus, and the concordance of etiologies in human and nonhuman primate alopecia remains an open question. However, Kramer et al. [2010] have documented the presence of inflammatory processes in alopecic rhesus, indicating a role for immune dysregulation. This finding makes it reasonable to assume that some alopecia in rhesus may be heritable. However, at this time we are not aware of any reports specifically investigating heritability of alopecia in nonhuman primates.

Implications

Our findings have implications for the evaluation of potential treatments for alopecia. If the time period for reversal of alopecia effects is not recognized, we risk discarding valid treatments since we will incorrectly conclude that they are ineffective. Alopecia from some causes may be easier to reverse than others. For example, alopecia known to be caused by nutritional deficiencies or allergens has been shown to be quickly reversed once the underlying cause is addressed [Baker et al., 1971; Swenerton & Hurley, 1980; Ovadia et al., 2005]. However, for the few intervention studies available attempting to address alopecia due to causes not clearly identified, it would appear that alopecia takes a minimum of several months to improve. For example, Dupuy et al. [2009] began documenting significant differences in alopecia only after 12 weeks of enrichment, while another study with a shorter evaluation period failed to find significant effects for a similar intervention [Runeson et al., 2011]. Our findings should serve as a caution to researchers to ensure an adequate observation period when evaluating potential treatments.

Our findings also highlight the possibility that not all alopecia is fixable by making changes to the immediate environment. Our findings provide support for the idea that alopecia continues to be influenced by earlier life events and environments, and for severely affected animals there may be an upper limit for what can be ameliorated later on. The environment of alopecic animals should not automatically be assumed to be problematic without also considering the potential impact of former environments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Robin Gold, David Ezekiel, and Dr. Paul Sampson in the University of Washington, Department of Statistics for their assistance with the data analysis. This research was supported by NIH grant P51OD010425 (Thomas Baillie, PI) and by NIH grant R24OD01180-15 to Melinda Novak at University of Massachusetts, Amherst with a subcontract to the University of Washington, Seattle (Julie Worlein, PI).

Contract grant sponsor: NIH; contract grant numbers: P51 OD010425, R24OD01180-15.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

REFERENCES

- Baker HJ, Bradford LG, Montes LF. 1971. Dermatophytosis due to Microsporum-canis in a rhesus monkey. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 159:1607–1611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardi B, Wanert F, Zoller M, et al. 2007. Alopecia areata in a rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Journal of Medical Primatology 36:124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisner B, Isbell L. 2008. Ground substrate affects activity budgets and hair loss in outdoor captive groups of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). American Journal of Primatology 70:1160–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellanca RU, Lee GH, Vogel K, et al. 2014. A simple alopecia scoring system for use in colony management of laboratory-housed primates. Journal of Medical Primatology 43:153–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coda AB, Hysa VQ, Seiffert-Sinha K, Sinha AA. 2010. Peripheral blood gene expression in alopecia areata reveals molecular pathways distinguishing heritability, disease and severity. Genes and Immunity 11:531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti G, Hansman C, Heckman JJ, et al. 2012. Primate evidence on the late health effects of early-life adversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109:8866–8871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EB, Suomi SJ. 2006. Hair loss and replacement cycles in socially housed, pregnant, rhesus macaques. American Journal of Primatology 68:58–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy AM, Wright AE, Musso MW, Fontenot M. 2009. Fleece tubes as treatment for alopecia associated with overgrooming or hair plucking behavior in adult female rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science 48:585–585. [Google Scholar]

- Honess PE, Gimpel JL, Wolfensohn SE, Mason GJ. 2005. Alopecia scoring: the quantitative assessment of hair loss in captive macaques. Alternatives to Laboratory Animals 33:193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackow C, Puffer N, Hordinsky M, et al. 1998. Alopecia areata and cytomegalovirus infection in twins: genes versus environment? Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 38:418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer J, Fahey M, Santos R, et al. 2010. Alopecia in rhesus macaques correlates with immunophenotypic alterations in dermal inflammatory infiltrates consistent with hypersensitivity etiology. Journal of Medical Primatology 39:112–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeker R, Bellanca RU, Lee GH, Thom JP, Worlein JM. 2014. Alopecia in three macaque species housed in a laboratory environment. American Journal of Primatology 75:38–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchins KR, Baker KC, Gilbert MH, et al. 2011. Application of the diagnostic evaluation for alopecia in traditional veterinary species to laboratory rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science 50:926–938. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz C, Coleman K, Worlein JM, Novak MA. 2013. Hair loss and hair-pulling in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science 52:4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th edition Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; p 246. [Google Scholar]

- Novak MA, Meyer JS. 2009. Alopecia: possible causes and treatments, particularly in captive nonhuman primates. Comparative Medicine 59:18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak MA, Hamel AF, Coleman K, et al. 2014. Hair loss and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis activity in captive rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science 53:261–266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill-Wagner P 1997. Hair today, gone tomorrow: dyemarking and shaving help track hair loss and growth in rhesus monkeys. American Journal of Primatology 42:138. [Google Scholar]

- Orion E, Wolf R. 2013. Psychological factors in skin diseases: stress and skin: facts and controversies. Clinics in Dermatology 31:707–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovadia S, Wilson SR, Zeiss CJ. 2005. Successful cyclosporine treatment for atopic dermatitis in a rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). Comparative Medicine 55: 192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardi A, Abeni D. 2001. Stressful life events and skin diseases: disentangling evidence from myth. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 70:118–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommeck I, Gottlieb DH, Strand SC, McCowen B. 2009. The effects of four nursery rearing strategies on infant behavioral development in rhesus macaques. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science 48:395–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runeson EP, Lee GH, Crockett CM, Bellanca RU. 2011. Evaluating paint rollers as an intervention for alopecia in monkeys in the laboratory (Macaca nemestrina). Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 14:138–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz HW, Kaumanns W, Neimeier KA, Kaup FJ. 2005. Dermatologic investigation of alopecia in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 36:229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz HW, Kaumanns W, Dix I, et al. 2006. Coat condition, housing condition and measurement of faecal cortisol metabolites-a non-invasive study about alopecia in captive rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Journal of Medical Primatology 35:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenerton H, Hurley LS. 1980. Zinc-deficiency in rhesus and bonnet monkeys, including effects on reproduction. Journal of Nutrition 110:575–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessey SH, Morrison JA. 1970. Molt in free-ranging rhesus monkeys, Macaca mulatta. Journal of Mammalogy 51: 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Williams R 2006. Generalized order logit/partial proportional odds models for ordinal dependent variables. The Stata Journal 6:58–82. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao FL, Yang S, Liu JB, et al. 2006. The epidemiology of childhood alopecia areata in China: a study of 226 patients. Pediatric Dermatology 23:13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]