Abstract

Despite their association with DNA mismatch repair (MMR) protein deficiency, colonic adenocarcinomas with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation have not been associated with improved survival compared with conventional adenocarcinomas in most studies. Recent studies indicate that increased T-cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment has a favorable prognostic effect in colonic adenocarcinoma. However, the prognostic effect of tumor-associated T cells has not been evaluated in histologic subtypes of colonic adenocarcinoma. We evaluated CD8-positive T-cell density in 259 patients with colonic adenocarcinoma, including 113 patients with tumors demonstrating mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation, using a validated automated quantitative digital image analysis platform and correlated CD8-positive T-cell density with histopathologic variables, MMR status, molecular alterations, and survival. CD8-positive T-cell densities were significantly higher for MMR protein-deficient tumors (P < 0.001), BRAF V600E mutant tumors (P = 0.004), and tumors with medullary differentiation (P < 0.001) but did not correlate with mucinous or signet ring cell histology (P > 0.05 for both). In the multivariable model of factors predicting disease-free survival, increased CD8-positive T-cell density was associated with improved survival both in the entire cohort (hazard ratio = 0.34, 95% confidence interval, 0.15–0.75, P = 0.008) and in an analysis of patients with tumors with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation (hazard ratio = 0.06, 95% confidence interval, 0.01–0.54, P = 0.01). The prognostic effect of CD8-positive T-cell density was independent of tumor stage, MMR status, KRAS mutation, and BRAF mutation. Venous invasion was the only other variable independently associated with survival in both the entire cohort and in patients with tumors with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation. In summary, our results indicate that the prognostic value of MMR protein deficiency is most likely attributed to increased tumor-associated CD8-positive T cells and that automated quantitative CD8 T-cell analysis is a better biomarker of patient survival, particularly in patients with tumors demonstrating mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation.

Keywords: colon cancer, colonic adenocarcinoma, mucinous, signet ring cell, medullary, CD8, image analysis, immunohistochemistry, prognosis, survival

An estimated 148,000 individuals are diagnosed with colorectal carcinoma each year, and ~53,000 will die from this disease, making colorectal carcinoma the third leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States.1 The treatment and prognosis of colon cancer is determined primarily by TNM staging but significant prognostic heterogeneity remains.2 DNA mismatch repair protein (MMR) protein deficiency has generally been associated with improved survival3–8; however, not all studies have verified the association of MMR protein deficiency and improved survival in patients with colon cancer.9,10 Mucinous, signet ring cell, and medullary differentiation are well-established features of colorectal adenocarcinomas with MMR protein deficiency.11 Despite their association with MMR protein deficiency, the prognostic impact of mucinous,12–14 signet ring cell,15–17 or medullary differentiation18 is still uncertain with some literature studies indicating that MMR protein deficiency is not always associated with improved survival in these histologic subtypes. These findings suggest that MMR status may not reliably predict clinical course in histologic subtypes of colon cancer and that additional biomarkers that can predict clinically aggressive disease may be helpful.

Immune cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment has been previously evaluated in colon cancer with many studies supporting its prognostic relevance.19–32 Among immune cells, CD8-positive T cells have been shown to be the predominant effector for anti-tumor immune response.33–35 However, a major impediment to the routine evaluation of CD8-positive T-cell density in the tumor microenvironment is the availability of a reproducible and reliable method easily accessible to pathology laboratories. The assessment of CD8-positive T cells within immunostained tissue sections has often been reported using manual counting methods, semi-quantitative visual assessment, or proprietary quantitative algorithms that are not routinely available in most laboratories.20,21 In addition, only a limited number of literature reports have included microsatellite instability (MSI) or MMR status as variables in the analysis of the prognostic effect of immune cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment of colon cancer. Last, to our knowledge, no prior study has specifically evaluated the prognostic impact of quantitative T-cell analysis in colonic adenocarcinoma with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation, features that are well-known to be associated with MMR protein deficiency.

The aim of this study was to assess a validated quantitative image analysis platform for CD8 T-cell density in a cohort of 259 colonic adenocarcinomas enriched for tumors with mucinous, signet ring cell, and medullary differentiation analyzed for histopathologic variables, MMR status, and KRAS and BRAF mutations, and correlate these findings with patient survival. In so doing, we demonstrate that CD8 T-cell density is a prognostic biomarker that is independent of MMR status and other histopathologic variables, particularly in tumors demonstrating mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Group

The clinicopathologic records of 259 patients with surgically resected primary colonic adenocarcinoma resected at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center between 2010 and 2015 were reviewed. The 259 colonic adenocarcinomas included a consecutive series of 161 MMR proficient colonic adenocarcinomas resected in a 2-year period (2011 through 2012) and a consecutive series of 98 MMR deficient colonic adenocarcinomas resected in a 6-year period (2010 through 2015) to enrich for patients with MMR deficient tumors. Patients with rectal adenocarcinomas were specifically excluded given their different therapeutic management compared with colonic adenocarcinoma. Patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy before resection were also specifically excluded. The type of initial surgical procedure, extent of disease, demographic information, and clinical follow-up were obtained from medical records under the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board (IRB# PR016040136).

Immunohistochemical and Quantitative Digital Image Analysis

CD8 immunohistochemistry (clone CD8/144B; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) was performed on one whole tissue section of the primary tumor containing the deepest extent of invasion for each case. The CD8 slides were digitized using an Aperio AT2 scanner (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) at ×40 magnification. The Aperio nuclear v9 algorithm was used to count the CD8-positive stained cells based on different classes of staining intensity (0, 1+, 2+, and 3+) as previously described.36 This algorithm has been previously optimized compared with a manual count of CD8-positive cells by immunohistochemistry and cross-validated with fluorescence-based CD8-positive T-cell quantification.36 The algorithm is a component of the commercially available Leica/Aperio image analysis platform. Briefly, in a prior study, manually counted CD8-positive cells were compared with the image analysis algorithm with a linear correlation between the manual count of 0.943.36 The fluorescence-based assessment of CD8 on serial sections from the same tissue also demonstrated good correlation with the image analysis algorithm.36 The Leica/Aperio algorithm divides staining intensity into 0, 1+, 2+, and 3+ categories. However, staining of any intensity (1+, 2+, or 3+) was scored as positive. The CD8-positive T-cell density was determined by dividing the number of CD8-positive T cells including cells stained with 3+, 2+, and 1+ intensity by the area in mm2 examined. The hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slide and corresponding CD8 immunostained slide for each case were manually annotated to outline the tumor core and the invasive margin, as previously described.19 The invasive margin was defined as the area including 0.5 mm extending into the tumor core and 1.0 mm beyond the tumor (Fig. 1). The tumor core was defined as the remainder of the tumor above the invasive margin. Areas of necrosis were specifically excluded from the area of analysis. CD8-positive T-cell densities were calculated by image analysis separately for the tumor core and invasive margin. The entire area of both the tumor core and the invasive margin were used to determine the CD8-positive T-cell density. The CD8-positive T-cell density analysis was performed blinded to patient outcomes, molecular alterations, MMR status, and histopathologic variables.

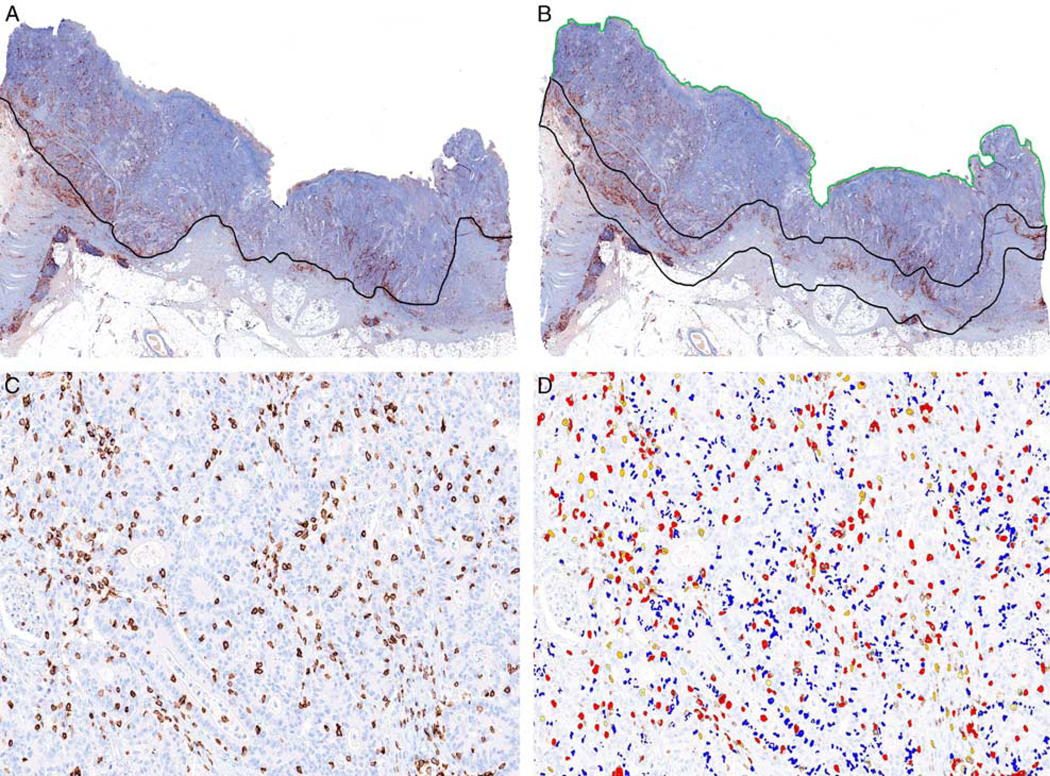

FIGURE 1.

A, Representative image of CD8 immunohistochemistry performed on a whole tissue section of colon cancer. The invasive front was manually annotated (black line) on the digitally scanned CD8 immunostained slide. B, The invasive margin was defined as the area including 0.5 mm extending into the tumor core and 1.0 mm beyond the tumor (demarcated by the black line). The tumor core was defined as the remainder of the tumor above the invasive margin (demarcated by the green line). C, CD8 immunohistochemistry identifying CD8-positive T cells within the tumor core. D, Automated CD8 image analysis algorithm identifying CD8-positive T cells of varying intensity (3+ intensity, red; 2+ intensity, orange; 1+ intensity, yellow). A subset of nonlymphocyte nuclei are labeled in blue color. The CD8-positive T-cell density was determined by dividing the number of CD8-positive T cells including cells stained with 3+, 2+, and 1+ intensity by the entire area in mm2 examined. Importantly, the entire area of both the tumor core and the invasive margin were used to determine the CD8-positive T-cell density. Analysis limited to “hot spot” regions of the tumor was not performed given the variability introduced by selection bias.

The discriminative accuracy of CD8-positive T-cell density in the tumor core and invasive margin was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) with the calculation of sensitivity and specificity. A risk score cutoff using the Youden index of the AUROC was chosen to separate patients into 3 categories (low, intermediate, and high) based on CD8-positive T-cell densities in the tumor core and invasive margin. Low CD8-positive T-cell density was defined as a tumor having CD8-positive T-cell density below the optimal cutoffs both in the tumor core and invasive margin. Intermediate CD8-positive T-cell density was defined as a tumor having CD8-positive T-cell density above the optimal cutoff in either the tumor core or invasive margin. High CD8-positive T-cell density was defined as a tumor having CD8-positive T-cell density above the optimal cutoffs in both the tumor core and invasive margin. MMR protein immunohistochemistry was performed on whole tissue sections as previously described.37

Pathologic Evaluation

Histologic examination of all pathology slides from all 259 cases was retrospectively performed by one pathologist (R.K.P.) and the following histologic features were recorded for each case: grade, stage, lymphatic invasion, venous invasion, perineural invasion, tumor budding, mucinous histology, signetring cell histology, medullary histology, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) by routine H&E-stained histologic evaluation, and Crohn-like peritumoral lymphocytic reaction, as previously described.37,38 Tumor grade was assessed for all tumors, including those with mucinous differentiation, using the World Health Organization (WHO) fifth edition criteria with high-grade defined as <50% gland formation, regardless of MMR status.11 The presence of TILs was assessed using the criteria outlined by Greenson et al39 Briefly, each histologic section of the tumor was assessed at low-power (×2 or ×4) objective magnification to identify the “hotspot” area with the most TILs. In the “hotspot” area, the number of TILs was counted in 5 consecutive HPFs (×40 objective). If on average ≥ 3 lymphocytes per HPF were identified within the tumor, the tumor was scored as positive for TILs. If on average <3 lymphocytes per HPF within the tumor were identified, the tumor was scored as negative for TILs. The Crohn-like peritumoral lymphocytic reaction was scored using criteria outlined by Ueno et al40 and defined as numerous large lymphoid aggregates present at the tumor periphery with at least one lymphoid aggregate measuring > 1 mm in diameter. The presence and proportion of tumor with mucinous or signet ring cell histology was recorded. Using WHO fifth edition criteria, adenocarcinomas with any proportion of tumor exhibiting pools of extracellular mucin were categorized as having a mucinous component while adenocarcinomas with > 50% composed of pools of extracellular mucin were categorized as mucinous adenocarcinoma.11 Medullary differentiation was assessed using WHO fifth edition criteria and defined as sheets of malignant cells with vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm exhibiting infiltration by lymphocytes and/or neutrophils and the presence of MMR protein deficiency by immunohistochemistry.11 For conventional colonic adenocarcinoma, tumor budding was assessed using the method advocated by the International Tumor Budding Consensus Conference (ITBCC)41 and adopted by the College of American Pathologists colorectal carcinoma protocol. Tumor budding was not assessed in colonic adenocarcinomas with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation as advocated by the ITBCC.

KRAS and BRAF V600E Mutational Analysis

Detection of BRAF mutations was performed using real-time polymerase chain reaction and post-polymerase chain reaction fluorescence melting curve analysis on LightCycler (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN), as previously described.42 This assay detects BRAF mutations in codons 599, 600, and 601. Detection of mutations in exon 2 (codons 12 and 13) and exon 3 (codon 61) of the KRAS gene was performed as previously described.43

Statistical Analysis

The normality of the distributions of continuous variables were examined using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. As the data were not normally distributed, nonparametric statistical tests were used. Comparisons of CD8-positive T-cell density and categorical variables were performed using Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Continuous variables were compared with the Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. χ2 or the Fisher exact tests were used to characterize the relationship between categorical variables, as appropriate.

Disease-free survival was the primary endpoint. Death occurring within 1 month of the initial operation was attributed to operative mortality and was not included in the survival analysis. Disease-free survival was defined as the time (measured in months) from the date of initial diagnosis to the date of distant disease recurrence (ie, tumor involving the peritoneum and/or other organs) and censored at the date of last clinical follow-up. Patients with stage IV disease at initial presentation were not included in the disease-free survival analysis. Survival rates were determined by the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between groups were evaluated by the log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated from a Cox proportional hazard model to identify individual predictors of survival. Multivariate analysis of significant or borderline significant individual risk factors (P ≤ 0.1) was performed using Cox proportional hazard regression to identify independent risk factors for survival. Data from univariate and multivariate analyses were reported as HRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistics were assessed using 2-sided tests with P-values <0.05 considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (for Windows 23; IBM, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Clinicopathologic Features of the Study Cohort

The clinicopathologic features of the 259 patients in the study cohort are detailed in Table 1. The study cohort was enriched for patients with MMR deficient tumors (38% of cases) and tumors with either mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation (44% of cases). Of the 113 patients with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation, 73% had deficient MMR protein expression. MMR protein deficiency was identified in 70% of tumors with mucinous differentiation and 69% of tumors with signet ring cell differentiation. All tumors classified as having medullary differentiation were required to be MMR protein deficient. One hundred patients had adenocarcinomas with mucinous differentiation, including 67 classified as adenocarcinomas with a mucinous component (< 50% extracellular mucin) and 33 classified as mucinous adenocarcinomas ( > 50% extra-cellular mucin). Thirteen patients (5%) had signet ring cell differentiation, 4 with signet ring cells comprising > 50% of the tumor and 9 with signet ring cells comprising <50% of the tumor. All 13 of the tumors with signet ring cell differentiation also exhibited extracellular mucin. Twenty-six patients (10%) had adenocarcinomas with medullary differentiation including 13 with adenocarcinomas comprised entirely of medullary differentiation and 13 that exhibited medullary histology comprising at least 25% of the overall tumor. Of the 26 cases of adenocarcinoma with medullary differentiation, extracellular mucin was identified in 13 cases. In total, 26 of 113 (23%) patients had tumors with histopathologic heterogeneity including components of the mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation within the same tumor.

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics of the Study Cohort With Correlation With CD8-positive T-cell Density as a Continuous Variable

| Clinicopathologic Features | n (%) | CD8/mm2 at Tumor Core, Median (Range) | CD8/mm2 at Invasive Margin, Median (Range) | CD8/mm2 at Tumor Center (P) | CD8/mm2 at Invasive Margin (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMR status | |||||

| MMR proficient | 161 (62) | 112 (14–1066) | 187 (27–1331) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| MMR deficient | 98 (38) | 214 (11–2321) | 284 (59–1588) | ||

| KRAS exon 2 or 3 | |||||

| Negative | 124 (61) | 142 (17–2321) | 209 (45–1588) | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Positive | 78 (39) | 108 (14–912) | 213 (27–1331) | ||

| BRAF V600E | |||||

| Negative | 179 (72) | 125 (14–1376) | 204 (27–1331) | 0.02 | 0.004 |

| Positive | 69 (28) | 167 (11–2321) | 289 (43–1588) | ||

| BRAF V600E positive and MMR proficient | |||||

| Absent | 237 (96) | 136 (11–2321) | 223 (27–1588) | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Present | 11 (4) | 161 (42–438) | 172 (53–374) | ||

| Venous invasion | |||||

| Absent | 183 (71) | 167 (11–2321) | 267 (45–1588) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Present | 76 (29) | 99 (22–523) | 171 (27–732) | ||

| Lymphatic invasion | |||||

| Absent | 115 (44) | 177 (11–1897) | 272 (50–1130) | 0.01 | 0.001 |

| Present | 144 (56) | 114 (14–2321) | 191 (27–1588) | ||

| Perineural invasion | |||||

| Absent | 192 (74) | 155 (11–2321) | 249 (45–1588) | 0.08 | 0.002 |

| Present | 67 (26) | 108 (14–1339) | 174 (27–1027) | ||

| Grade | |||||

| Low | 212 (82) | 133 (11–1186) | 226 (27–948) | 0.04 | 0.4 |

| High | 47 (18) | 190 (31–2321) | 222 (56–1588) | ||

| TILs by routine H&E evaluation | |||||

| Absent | 163 (63) | 99 (14–760) | 179 (27–1050) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Present | 96 (37) | 281 (11–2321) | 326 (66–1588) | ||

| Crohn-like peritumoral reaction | |||||

| Absent | 183 (71) | 111 (11–1376) | 188 (27–1050) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Present | 76 (29) | 234 (34–2321) | 318 (66–1588) | ||

| Mucinous histology | |||||

| Absent | 159 (61) | 125 (14–2321) | 208 (27–1588) | 0.17 | 0.07 |

| Present | 100 (39) | 158 (11–1897) | 255 (50–1130) | ||

| Signet ring cell histology | |||||

| Absent | 246 (95) | 145 (11–2321) | 230 (27–1588) | 0.07 | 0.2 |

| Present | 13 (5) | 92 (31–682) | 172 (71–423) | ||

| Medullary histology | |||||

| Absent | 233 (90) | 126 (11–1186) | 212 (27–1331) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Present | 26 (10) | 388 (44–2321) | 413 (59–1588) | ||

| Tumor location* | |||||

| Right colon | 172 (67) | 131 (11–2321) | 203 (27–1588) | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| Left colon | 85 (33) | 151 (22–1366) | 249 (30–908) | ||

| Tumor budding per 0.785 mm2 | |||||

| 0–9 | 206 (80) | 166 (11–2321) | 258 (45–1588) | 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 10 | 53 (20) | 103 (22–1186) | 170 (27–1331) | ||

| Stage | |||||

| I–II | 142 (55) | 181 (22–2321) | 283 (55–1588) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| III | 83 (32) | 119 (11–1376) | 179 (30–1331) | ||

| IV | 34 (13) | 86 (14–304) | 171 (27–566) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 120 (46) | 159 (22–1376) | 226 (27–1050) | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Female | 139 (54) | 127 (11–2321) | 222 (30–1588) | ||

For 2 patients, tumor location could not be determined.

Overall, 225 patients (87%) had stage I to III tumors. Two hundred fourteen (214/225, 95%) patients with stage I to III disease had clinical follow-up data for disease-free survival analysis with a median follow-up interval of 44 months (range: 1 to 100 mo) from the time of initial diagnosis. There were 33 patients with tumor recurrence occurring between 2 and 85 months from the time of diagnosis.

Receiver operating characteristic curves were generated for CD8-positive T-cell densities in the tumor core and invasive margin using tumor recurrence as the anchor (Supplemental Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PAS/A912). The AUROC for CD8-positive T-cell densities in the invasive margin was 0.67 with an optimal cutoff of 182/ mm2 achieving a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 60% for tumor recurrence. The AUROC for CD8-positive T-cell densities in the tumor core was 0.68 with an optimal cutoff of 129/ mm2 achieving a sensitivity of 61% and specificity of 72% for tumor recurrence. Using these optimal cutoffs, patients were separated into 3 categories (low, intermediate, and high) based on CD8-positive T-cell densities in the tumor core and invasive margin. High, intermediate, and low CD8-positive T-cell density was identified in 62%, 22%, and 15% of MMR protein-deficient tumors and in 37%, 22%, and 41% MMR protein proficient tumors (P < 0.001), respectively. Subsequent survival analyses were performed using these categories.

CD8-positive T-cell Density Correlates With Clinicopathologic and Molecular Characteristics

CD8-positive T-cell densities at the invasive margin and tumor core were evaluated for all 259 colonic adenocarcinomas and correlated with several clinicopathologic variables (Table 1). For the entire cohort, CD8-positive T-cell density was significantly higher in the invasive margin compared with the tumor core (median 223/mm2 [interquartile range = 202] vs. 137/mm2 [interquartile range = 199], P < 0.001), including for both MMR protein deficient and MMR protein proficient colonic adenocarcinomas (P = 0.007 and <0.001, respectively). CD8-positive T-cell densities in the tumor core and invasive margin were significantly higher for MMR protein-deficient tumors (P < 0.001) and for BRAF V600E mutant tumors (P < 0.05). However, CD8-positive T-cell densities were not significantly associated with BRAF V600E mutation in the setting of MMR protein proficient tumors or with KRAS exon 2 or 3 mutation status (P > 0.05 for both). Medullary differentiation was also associated with higher median CD8-positive T-cell densities in the tumor core and invasive margin (P < 0.001 for both) while mucinous and signet ring cell histology did not correlate with CD8-positive T-cell density. Higher median CD8-positive T-cell densities in the tumor core and invasive margin were identified in tumors with a lack of venous invasion (P < 0.001 for both), lack of lymphatic invasion (P < 0.05 for both), and lack of high tumor budding (P ≤ 0.001). Last, higher median CD8-positive T-cell densities in the tumor core and invasive margin were significantly more often observed in stage I to II tumors compared with stage III and IV tumors (P < 0.001 for both).

Patients were separated into 3 categories (low, inter- mediate, and high CD8-positive T-cell density) based on CD8-positive T-cell densities in the tumor core and invasive margin (Table 2). Compared with tumors with low CD8- positive T-cell density, tumors with intermediate or high CD8-positive T-cell density were more likely to be stage I to II (P < 0.001) and MMR protein deficient (P < 0.001). Venous invasion (P < 0.001), lymphatic invasion (P = 0.004), and perineural invasion (P = 0.008) were more often observed in tumors with low CD8-positive T-cell density. There was no statistically significant difference in KRAS or BRAF mutation status or mucinous differentiation between these categories (all with P > 0.05).

TABLE 2.

Correlation of Low, Intermediate, and High CD8-positive T-cell Density With Clinicopathologic Variables

| n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical and Pathologic Features | High CD8-positive T-cell Density | Intermediate CD8-positive T-cell Density | Low CD8-positive T-cell Density | P |

| No. patients | 120 | 58 | 81 | NA |

| Sex (male/female) | 57 (48)/63 (52) | 26 (45)/32 (55) | 37 (46)/44 (54) | 0.9 |

| Age, median (IQR) (y) | 68 (17) | 74 (18) | 71 (15) | 0.1 |

| Location* | ||||

| Right colon | 74 (63) | 39 (67) | 59 (73) | 0.3 |

| Left colon | 44 (37) | 19 (33) | 22 (27) | |

| Stage | ||||

| I-II | 83 (69) | 34 (59) | 25 (31) | < 0.001 |

| III | 31 (26) | 14 (24) | 38 (47) | |

| IV | 6 (5) | 10 (17) | 18 (22) | |

| MMR status | ||||

| MMR protein deficient | 61 (51) | 22 (38) | 15 (19) | < 0.001 |

| MMR protein proficient | 59 (49) | 36 (62) | 66 (81) | |

| KRAS exon 2 or 3 mutation present | 29/87 (33) | 20/44 (45) | 29/71 (41) | 0.4 |

| BRAF V600E mutation present | 36/113 (32) | 19/57 (33) | 14/78 (18) | 0.06 |

| TILs (average ≥ 3 lymphocytes/HPF) by routine H&E assessment | 72 (60) | 13 (22) | 11 (14) | < 0.001 |

| Crohn-like peritumoral lymphocytic reaction by routine H&E assessment | 52 (43) | 16 (28) | 8 (10) | < 0.001 |

| Mucinous differentiation | 51 (43) | 25 (43) | 24 (30) | 0.1 |

| < 50% | 40 (33) | 17 (29) | 10 (12) | |

| > 50% | 11 (9) | 8 (14) | 14 (17) | |

| Signet ring cell differentiation | 2 (2) | 5 (9) | 6 (7) | 0.07 |

| Medullary differentiation | 21 (18) | 2 (3) | 3 (4) | 0.001 |

| Venous invasion | 20 (17) | 17 (29) | 39 (48) | < 0.001 |

| Lymphatic invasion | 56 (47) | 31 (53) | 57 (70) | 0.004 |

| Perineural invasion | 23 (19) | 13 (22) | 31 (38) | 0.008 |

For 2 patients, tumor location could not be determined.

NA indicates not available.

CD8-positive T-cell Density Is an Independent Predictor of Recurrence in Tumors With Mucinous, Signet Ring Cell, or Medullary Differentiation

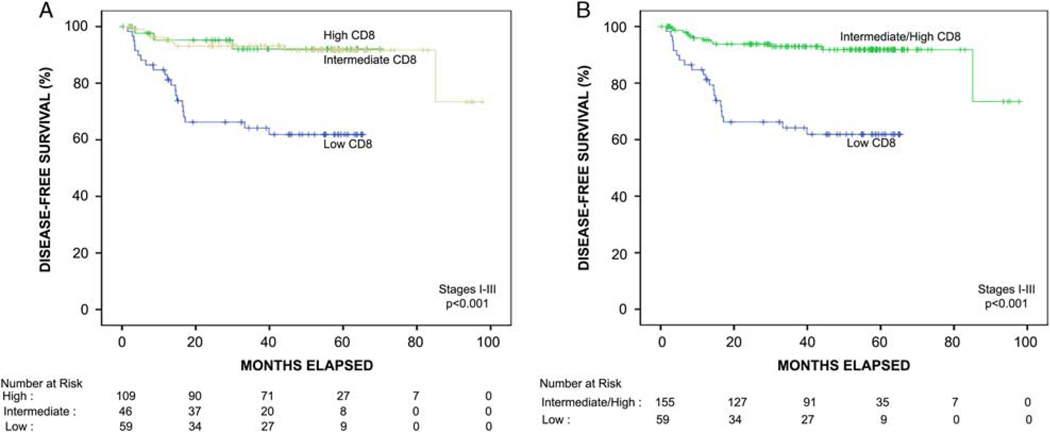

For patients with stage I to III disease with clinical follow-up in the entire cohort (N = 214), both intermediate and high CD8-positive T-cell densities were associated with improved disease-free survival (P = 0.001 and <0.001, respectively) compared with patients with low CD8-positive T-cell densities (Fig. 2). There was no significant difference in disease-free survival between patients with intermediate and high CD8-positive T-cell densities (P = 0.9). Given the similar molecular, histopathologic, and survival characteristics for patients with intermediate and high CD8-positive T-cell densities, these 2 patient groups were combined into 1 group (intermediate/high) (Fig. 2). Patients with low CD8-positive T-cell density were compared with patients with intermediate/high CD8-positive T-cell density in the subsequent analyses.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival function of the entire cohort of patients with stage I to III colon cancer stratified by automated quantitative CD8 analysis. A, Patients with high CD8-positive T-cell density (yellow line) had significantly improved disease-free survival compared with patients with low CD8-positive T-cell density (blue line) (P < 0.001). Patients with intermediate CD8-positive T-cell density (green line) had significantly improved disease-free survival compared with patients with low CD8-positive T-cell density (P = 0.001). There was no significant difference in disease-free survival between patients with intermediate versus high CD8-positive T-cell density (P = 0.9). B, Patients with intermediate or high CD8-positive T-cell density were combined into one category for subsequent survival analysis and had significantly improved disease-free survival compared with patients with low CD8-positive T-cell density (P < 0.001).

Using Cox proportional hazards modeling for stage I to III patients with clinical follow-up in the entire cohort (N = 214) (Table 3), features associated with reduced disease-free survival on univariate analysis include stage III disease (P < 0.001), venous invasion (P < 0.001), lymphatic invasion (P = 0.001), perineural invasion (P = 0.004), and high tumor budding (P < 0.001). MMR protein deficiency (P = 0.008), high/intermediate CD8-positive T-cell density (P < 0.001), TILs by routine H&E assessment (P = 0.01), and Crohn-like peritumoral lymphocytic reaction by routine H&E assessment (P = 0.02) were associated with improved disease-free survival. In the multivariable model, the prognostic effect of CD8- positive T-cell density on disease-free survival was independent of tumor stage, MMR status, and H&E assessment of TILs and Crohn-like peritumoral lymphocytic reaction. Patients with tumors demonstrating high/intermediate CD8-positive T-cell density were associated with significantly improved disease-free survival (HR = 0.34, 95% CI, 0.15–0.75, P = 0.008). The presence of venous invasion was the only other independent predictor of disease-free survival (HR = 3.15, 95% CI, 1.23–8.05, P = 0.02).

TABLE 3.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Disease-free Survival in Patients With Stage I to III Colon Cancer (Entire Cohort)

| Disease-free Survival (Stage I-III) (Entire Cohort, N=214) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

| Clinicopathologic Factors | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P |

| Age | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) | 0.2 | — | — |

| Stage I–II (vs. III) | 0.16 (0.07–0.36) | < 0.001 | 0.45 (0.16–1.26) | 0.1 |

| High grade (WHO fifth edition criteria) | 1.03 (0.42–2.50) | 1.0 | — | — |

| High/intermediate CD8-positive T-cell density | 0.18 (0.09–0.37) | < 0.001 | 0.34 (0.15–0.75) | 0.008 |

| MMR protein deficient | 0.30 (0.12–0.73) | 0.008 | 0.93 (0.27–3.25) | 0.9 |

| Venous invasion | 7.37 (3.55–15.29) | < 0.001 | 3.15 (1.23–8.05) | 0.02 |

| Lymphatic invasion | 5.06 (2.09–12.27) | < 0.001 | 1.55 (0.50–4.84) | 0.5 |

| Perineural invasion | 3.09 (1.55–6.19) | 0.001 | 0.77 (0.34–1.74) | 0.5 |

| High tumor budding | 3.90 (1.93–7.92) | < 0.001 | 1.66 (0.77–3.59) | 0.2 |

| TILs by routine H&E assessment | 0.33 (0.13–0.80) | 0.01 | 1.36 (0.32–5.86) | 0.7 |

| Crohn-like peritumoral lymphocytic reaction by routine H&E assessment | 0.30 (0.11–0.80) | 0.02 | 0.79 (0.22–2.78) | 0.7 |

| KRAS exon 2 or 3 mutant | 0.90 (0.41–1.99) | 0.8 | — | — |

| BRAF V600E mutant | 0.63 (0.27–1.46) | 0.3 | — | — |

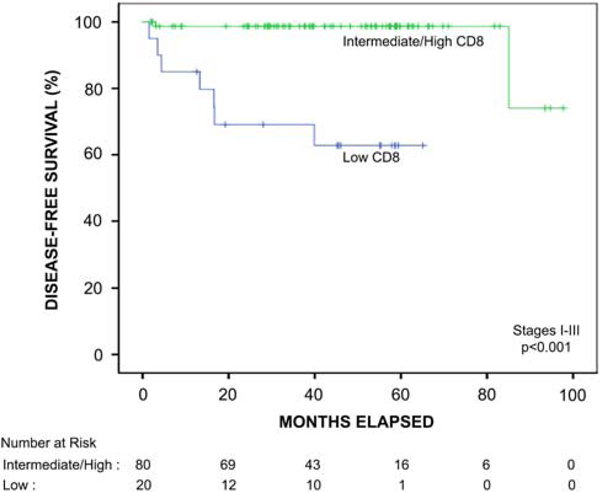

The results were similar when analyzing the subset of colonic adenocarcinomas with mucinous, signet ring cell, and medullary differentiation (N = 100) (Fig. 3, Table 4). For stage I to III patients with adenocarcinomas with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation, intermediate/high CD8-positive T-cell density was significantly associated with improved disease-free survival compared with low CD8-positive T-cell density (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival function of the patients with stage I to III colon cancer with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation stratified by automated quantitative CD8 analysis. In this patient subgroup, the presence of intermediate or high CD8-positive T-cell density was significantly associated with improved disease-free survival compared with patients with low CD8-positive T-cell density (P < 0.001).

TABLE 4.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Disease-free Survival in Patients With Colonic Adenocarcinoma With Mucinous, Signet Ring Cell, or Medullary Differentiation

| Mucinous, Signet Ring Cell, or Medullary Differentiation (N=100) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

| Clinicopathologic Factors | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P |

| Age | 1.05 (0.98–1.12) | 0.2 | — | — |

| Stage I–II (vs. III) | 0.12 (0.025–0.57) | 0.008 | 0.36 (0.05–2.67) | 0.3 |

| High grade (WHO fifth edition criteria) | 1.48 (0.39–5.57) | 0.6 | — | — |

| High/intermediate CD8-positive T-cell density | 0.34 (0.04–0.27) | 0.002 | 0.06 (0.01–0.54) | 0.01 |

| MMR protein deficient | 0.35 (0.09–1.14) | 0.1 | 0.53 (0.11–2.61) | 0.4 |

| Venous invasion | 16.59 (3.95–39.79) | < 0.001 | 8.64 (1.33–25.96) | 0.02 |

| Lymphatic invasion | 4.28 (0.89–20.63) | 0.07 | 0.71 (0.08–6.56) | 0.7 |

| Perineural invasion | 2.22 (0.53–9.38) | 0.3 | — | — |

| TILs by routine H&E assessment | 0.73 (0.18–3.07) | 0.7 | — | — |

| Crohn-like peritumoral lymphocytic reaction by routine H&E assessment | 0.44 (0.11–1.81) | 0.3 | — | — |

| KRAS exon 2 or 3 mutant | 2.44 (0.34–17.31) | 0.4 | — | — |

| BRAF V600E mutant | 0.90 (0.23–3.62) | 0.9 | — | — |

Of the 89 patients with adenocarcinomas with mucinous differentiation, only 1 of 70 (1%) with intermediate/high CD8-positive T-cell density developed tumor recurrence while 6 of 19 (32%) with low CD8-positive T-cell density developed tumor recurrence (P < 0.001). Of the 9 patients, adenocarcinomas with signet ring cell differentiation with clinical follow-up, 2 patients with low CD8-positive T-cell density developed tumor recurrence while no patient with intermediate/high CD8-positive T-cell density developed tumor recurrence. A total of 20 patients with adenocarcinomas with medullary differentiation had a clinical follow-up, and 1 patient with low CD8-positive T-cell density developed tumor recurrence following surgical resection despite the presence of MLH1 protein deficiency within the tumor (Supplemental Fig. 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/PAS/A913).

Using Cox proportional hazards modeling for stage I to III patients with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation (Table 4), features associated with reduced disease-free survival on the univariate analysis included stage III disease (P = 0.008) and venous invasion (P < 0.001). High/intermediate CD8-positive T-cell density was associated with improved disease-free survival (P < 0.001). MMR protein deficiency within the tumor was associated with improved survival; however, this was of borderline significance (P = 0.1). In the multivariable model, high/intermediate CD8-positive T-cell density was a predictor of improved disease-free survival (HR = 0.06, 95% CI, 0.01–0.54, P = 0.01) independent of tumor stage and MMR status (Fig. 4). The presence of venous invasion was the only other independent predictor of disease-free survival (HR = 8.64, 95% CI, 1.33–25.96, P = 0.02).

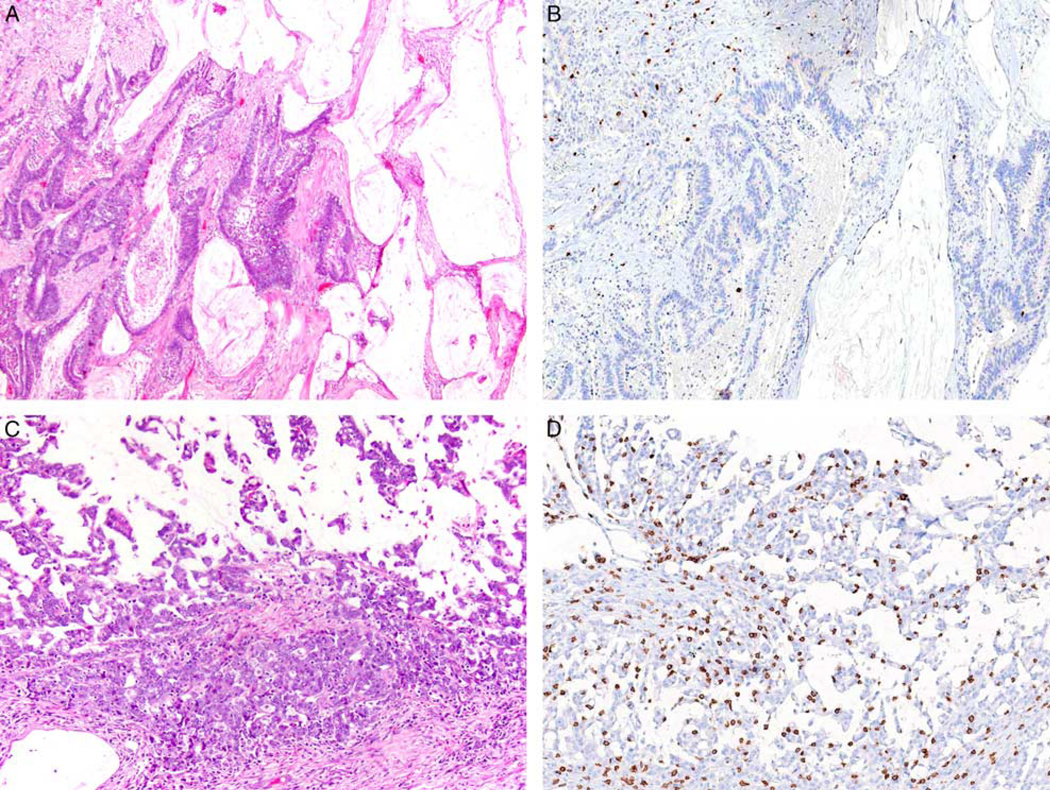

FIGURE 4.

A, A 74-year-old woman had a surgically resected stage II (pT3N0) MLH1-deficient BRAF V600E mutant mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ascending colon. B, The tumor demonstrated low CD8-positive T-cell density and the patient developed tumor recurrence following surgical resection. C, A 63-year-old woman had a surgically resected stage II (pT3N0) MLH1-deficient BRAF V600E mutant mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ascending colon. D, The tumor demonstrated high CD8-positive T-cell density and the patient did not develop tumor recurrence with 94 months of clinical follow-up following resection.

DISCUSSION

The primary motivation for this study was to evaluate the prognostic significance of CD8-positive T-cell density in a cohort of patients with molecularly annotated colonic adenocarcinoma, including those with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation, with rigorous histopathologic analysis of features associated with outcome. Our results indicate that CD8-positive T-cell density is a predictor of survival in colonic adenocarcinoma independent of tumor stage, MMR status, and other histopathologic variables that are routinely assessed in colon cancer. In our analysis, only CD8-positive T-cell density and venous invasion were independent predictors of disease-free survival, both within the entire cohort and within the subset of tumors with mucinous, signet ring cell, and medullary differentiation. These results suggest the prognostic value of MMR protein deficiency is most likely attributed to increased CD8-positive tumor-associated T cells and that automated quantitative CD8 T-cell analysis in colonic adenocarcinoma may be a better prognostic biomarker of patient survival, particularly in patients with histologic subtypes of colonic adenocarcinoma.

Prognosis in patients with colon cancer is based on a number of histopathologic factors, including MMR protein expression within the tumor.44 Although the tumor stage remains the most important prognostic variable in colon cancer, between 20% to 40% of patients with nonmetastatic colon cancer will develop tumor recurrence following surgical resection.2 MMR protein deficient tumors are more often identified in patients with stage II disease (~20%) or stage III (9% to 12%).8,10,45–47 In addition, mucinous, signet ring cell, and medullary differentiation are well-established features of colorectal adenocarcinomas with MMR protein deficiency.11 Despite their association with MMR protein deficiency, colorectal carcinomas with mucinous,12–14 signet ring cell,15–17 or medullary differentiation18 have not been associated with improved survival compared with conventional colorectal adenocarcinomas in most studies. A number of prior studies have also demonstrated that colorectal adenocarcinomas with a mucinous component (< 50% extracellular mucin) and colorectal mucinous adenocarcinomas ( > 50% extracellular mucin) have similar clinicopathologic, molecular, and survival characteristics indicating that any proportion of extracellular mucin within an adenocarcinoma is biologically relevant and distinct from nonmucinous conventional adenocarcinoma.12,13 MMR protein deficiency is also seen in nearly identical proportions of colorectal adenocarcinomas with mucinous differentiation whether mucin is present in 1% to 50% or > 50% of the tumor.38 MMR protein deficiency has not been shown to have independent prognostic value in colorectal adenocarcinoma with mucinous differentiation.11,48 Similarly, MMR protein deficiency in colorectal adenocarcinomas with signet ring cell differentiation is also not associated with improved prognosis, including in those tumors with associated extracellular mucin.15,17 Last, the impact on survival of medullary differentiation in colorectal carcinoma is still uncertain. In a recent meta-analysis including 462 medullary carcinomas, there was no significant survival difference between medullary carcinoma and conventional adenocarcinoma.18 However, in many of the prior studies of medullary carcinoma included in the meta-analysis, it is unclear if MMR protein deficiency was used as an inclusion criterion for classifying a tumor as exhibiting medullary differentiation, as in our current study.

Our data suggest that MMR status may not reliably predict clinical course in adenocarcinomas with histologic components of the mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation and that CD8-positive T-cell density is a better predictor of aggressive clinical behavior. A number of studies have demonstrated that CD8-positive T-cell infiltration within colon cancer has prognostic implications.19–32 However, to our knowledge, our study is the first to correlate automated quantitative CD8 T-cell digital image analysis in these histologic subtypes of colonic adenocarcinomas. A major impediment to the routine evaluation of infiltrating lymphocytes is the availability of a reproducible and reliable method to quantify the amount of lymphocytes within the tissue. A number of different techniques have been employed to score lymphocyte density with most studies using manual counts or semiquantitative visual assessment of immunohistochemically stained tissue sections. In a study of 1265 patients, Williams et al49 demonstrated that high TILs (defined as ≥ 2 TILs/HPF by manual count on routine H&E stained sections) correlated with patient outcome independent of MMR status and tumor stage. In our study, a high TIL count identified on routine H&E stained sections was associated with improved disease-free survival on univariate analysis but was not predictive of outcome in the multivariable model that included automated quantitative CD8 T-cell analysis. These results suggest that automated quantitative CD8 T-cell analysis is better than manual TIL assessment at predicting survival.

The largest studies to date analyzing the prognostic impact of automated quantitative T-lymphocyte assessment in the tumor microenvironment have used the Immuno-score assay that evaluates the density of CD3-positive and CD8-positive T cells at the tumor core and invasive margin.20,21,50 Similar to the results of the current study, Pages and colleagues and Mlecnik and colleagues both demonstrated that the Immunoscore is a predictor of disease-free survival for patients with colon cancer independent of MMR status and stage. In the initial analysis of the Immunoscore in 599 patients with colorectal carcinoma, Mlecnik et al50 demonstrated that in a multivariable model only the Immunoscore was an independent prognostic biomarker for disease-free survival while stage and all other histopathologic variables were not predictive. In a subsequent international validation of the Immunoscore using 14 centers with 3539 patients, Pages et al20 demonstrated that the Immunoscore was a stronger predictor of survival compared with T stage, N stage, MSI status, venous invasion, and perineural invasion. Our study adds to this growing literature and suggests that prognosis for colonic adenocarcinomas with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation is also affected by tumor-associated CD8-positive T-lymphocytes and the prognostic effect is independent of tumor stage and MSI status. However, additional large, well-characterized patient populations with colon cancer with mucinous, signet ring cell or medullary differentiation with and without MMR protein deficiency and with extended follow-up are needed to further determine the prognostic impact of CD8-positive T-cell density.

Immune cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment may also be relevant in predicting patient response to both conventional and immune-based therapy in colon cancer. While many patients with MMR deficient tumors demonstrate responsiveness to anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1) therapy, not all patients with MMR deficient colon cancer respond to this treatment.51,52 Factors underlying the lack of response to anti-PD1 therapy in patients with MMR deficient colonic cancer are unclear but may be related to the density of infiltrating T cells in the tumor microenvironment. Additional study is also needed to determine if patients with MMR proficient tumors with high T-cell density in the tumor micro-environment could benefit from anti-PD1 therapy.

The strengths of our study include rigorous molecular and histopathologic analysis of variables that are routinely assessed in colon cancer. We also employed an internally validated automated quantitative digital image analysis platform that could be adapted to routine clinical practice in any pathology laboratory. Our analysis has limitations including the retrospective design and the lack of rigorously standardized treatment in retrospective analyses. Our study also represents a study on colon cancers resected at a large academic medical center with its inherent referral bias. In addition, we were unable to validate our CD8-positive T-cell density analysis with the Immunoscore assay as the Immunoscore assay is a commercial product that uses a separate software and digital image analysis system (HalioDx, France). Validation of the prognostic impact of the CD8-positive T-cell density determined by the Leica/Aperio algorithm used in this study in larger cohorts of patients with colon cancer with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation with and without MMR protein deficiency is needed. Last, lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment may reside within the tumor cell clusters, within the stroma, or within both compartments. Given the variability introduced by selection bias related to how tumor subcompartments are determined and annotated, a subanalysis of CD8 density within tumor epithelium and tumor stroma was not performed.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that CD8-positive T-cell density is an independent predictor of survival in colon cancer, particularly for patients with colonic adenocarcinoma with mucinous, signet ring cell, or medullary differentiation. The prognostic effect of CD8 T-cell density is independent of MMR status suggesting that the prognostic benefit of MMR protein deficiency is most likely attributed to increased CD8-positive T cells. Although more study is needed, CD8-positive T-cell density may be a useful biomarker to include as part of the routine comprehensive pathologic risk assessment in histologic subtypes of colonic adenocarcinoma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relationships with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

Footnotes

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.ajsp.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bockelman C, Engelmann BE, Kaprio T, et al. Risk of recurrence in patients with colon cancer stage II and III: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent literature. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popat S, Hubner R, Houlston RS. Systematic review of microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:609–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klingbiel D, Saridaki Z, Roth AD, et al. Prognosis of stage II and III colon cancer treated with adjuvant 5-fluorouracil or FOLFIRI in relation to microsatellite status: results of the PETACC-3 trial. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribic CM, Sargent DJ, Moore MJ, et al. Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349: 247–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Thibodeau SN, et al. DNA mismatch repair status and colon cancer recurrence and survival in clinical trials of 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:863–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G, et al. Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3219–3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohan HM, Ryan E, Balasubramanian I, et al. Microsatellite instability is associated with reduced disease specific survival in stage III colon cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:1680–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim GP, Colangelo LH, Wieand HS, et al. Prognostic and predictive roles of high-degree microsatellite instability in colon cancer: a National Cancer Institute-National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Collaborative Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:767–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gkekas I, Novotny J, Pecen L, et al. Microsatellite instability as a prognostic factor in stage II colon cancer patients, a meta-analysis of published literature. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:6563–6574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagtegaal ID, Arends MJ, Salto-Tellez M. Colorectal adenocarcinoma. In: Odze RD, Paradis V, Park YN, Rugge M, Salto-Tellez M, Schirmacher P, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours: Digestive System Tumours, 5th ed Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2019:177–187. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez RS, Cates JMM, Washington K. Associations among histological characteristics and patient outcomes in colorectal carcinoma with a mucinous component. Histopathology. 2019;74:406–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogino S, Brahmandam M, Cantor M, et al. Distinct molecular features of colorectal carcinoma with signet ring cell component and colorectal carcinoma with mucinous component. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verhulst J, Ferdinande L, Demetter P, et al. Mucinous subtype as prognostic factor in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartman DJ, Nikiforova MN, Chang DT, et al. Signet ring cell colorectal carcinoma: a distinct subset of mucin-poor microsatellite-stable signet ring cell carcinoma associated with dismal prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:969–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sung CO, Seo JW, Kim KM, et al. Clinical significance of signet-ring cells in colorectal mucinous adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:1533–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kakar S, Smyrk TC. Signet ring cell carcinoma of the colorectum: correlations between microsatellite instability, clinicopathologic features and survival. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pyo JS, Sohn JH, Kang G. Medullary carcinoma in the colorectum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Pathol. 2016;53:91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoon HH, Shi Q, Heying EN, et al. Intertumoral heterogeneity of CD3(+) and CD8(+) T-Cell densities in the microenvironment of DNA mismatch-repair-deficient colon cancers: implications for prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:125–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pages F, Mlecnik B, Marliot F, et al. International validation of the consensus Immunoscore for the classification of colon cancer: a prognostic and accuracy study. Lancet. 2018;391:2128–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mlecnik B, Bindea G, Angell HK, et al. Integrative analyses of colorectal cancer show immunoscore is a stronger predictor of patient survival than microsatellite instability. Immunity. 2016;44:698–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ling A, Edin S, Wikberg ML, et al. The intratumoural subsite and relation of CD8(+) and FOXP3(+) T lymphocytes in colorectal cancer provide important prognostic clues. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2551–2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards CH, Roxburgh CS, Powell AG, et al. The clinical utility of the local inflammatory response in colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deschoolmeester V, Baay M, Van Marck E, et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes: an intriguing player in the survival of colorectal cancer patients. BMC Immunol. 2010;11:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee WS, Park S, Lee WY, et al. Clinical impact of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for survival in stage II colon cancer. Cancer. 2010;116: 5188–5199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salama P, Phillips M, Grieu F, et al. Tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+ T regulatory cells show strong prognostic significance in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinicrope FA, Rego RL, Ansell SM, et al. Intraepithelial effector (CD3+)/regulatory (FoxP3+) T-cell ratio predicts a clinical outcome of human colon carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1270–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki H, Chikazawa N, Tasaka T, et al. Intratumoral CD8(+) T/ FOXP3 (+) cell ratio is a predictive marker for survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:653–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flaherty DC, Lavotshkin S, Jalas JR, et al. Prognostic utility of immunoprofiling in colon cancer: results from a prospective, multicenter nodal ultrastaging trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223:134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nosho K, Baba Y, Tanaka N, et al. Tumour-infiltrating T-cell subsets, molecular changes in colorectal cancer, and prognosis: cohort study and literature review. J Pathol. 2010;222:350–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emile JF, Julie C, Le Malicot K, et al. Prospective validation of a lymphocyte infiltration prognostic test in stage III colon cancer patients treated with adjuvant FOLFOX. Eur J Cancer. 2017;82:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fridman WH, Pages F, Sautes-Fridman C, et al. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mantovani A, Romero P, Palucka AK, et al. Tumour immunity: effector response to tumour and role of the microenvironment. Lancet. 2008;371:771–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity. 2013;39:782–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartman DJ, Ahmad F, Ferris RL, et al. Utility of CD8 score by automated quantitative image analysis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2018;86:278–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma C, Olevian D, Miller C, et al. SATB2 and CDX2 are prognostic biomarkers in DNA mismatch repair protein deficient colon cancer. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:1217–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olevian DC, Pai RK. Histologic features do not reliably predict mismatch repair protein deficiency in colorectal carcinoma: the results of a 5-year prospective evaluation. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2018;26:231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenson JK, Bonner JD, Ben-Yzhak O, et al. Phenotype of microsatellite unstable colorectal carcinomas: well-differentiated and focally mucinous tumors and the absence of dirty necrosis correlate with microsatellite instability. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:563–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ueno H, Hashiguchi Y, Shimazaki H, et al. Objective criteria for Crohn-like lymphoid reaction in colorectal cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:434–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lugli A, Kirsch R, Ajioka Y, et al. Recommendations for reporting tumor budding in colorectal cancer based on the International Tumor Budding Consensus Conference (ITBCC) 2016. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:1299–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yousem SA, Nikiforova M, Nikiforov Y. The histopathology of BRAF-V600E-mutated lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008; 32:1317–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landau MA, Zhu B, Akwuole FN, et al. Site-specific differences in colonic adenocarcinoma: KRAS mutations and high tumor budding are more frequent in cecal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benson AB III, Venook AP, Cederquist L, et al. Colon cancer, version 1.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:370–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koopman M, Kortman GA, Mekenkamp L, et al. Deficient mismatch repair system in patients with sporadic advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, et al. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60–00 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:466–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sinicrope FA, Shi Q, Smyrk TC, et al. Molecular markers identify subtypes of stage III colon cancer associated with patient outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:88–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andrici J, Farzin M, Sioson L, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency as a prognostic factor in mucinous colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol. 2016; 29:266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams DS, Mouradov D, Jorissen RN, et al. Lymphocytic response to tumour and deficient DNA mismatch repair identify subtypes of stage II/III colorectal cancer associated with patient outcomes. Gut. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, et al. Histopathologic-based prognostic factors of colorectal cancers are associated with the state of the local immune reaction. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.