Abstract

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma (BCC) are two major types of skin cancer derived from keratinocytes. SCC is a more aggressive type of cancer than BCC in humans. One significant difference between SCC and BCC is that SCC development is generally associated with cell dedifferentiation and morphological changes. When SCC is converted to spindle cell carcinoma, the latest stage of cancer, the tumor cells change to a fibroblastic cell morphology (epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition) and lose their differentiation markers. Recently, several laboratories have reported altered IκB kinase α (IKKα) protein localization, downregulated IKKα, and IKKα gene deletions and mutations in human SCCs of the skin, lung, esophagus, and neck and head. In addition, IKKα reduction promotes chemical carcinogen- and ultraviolet B-induced skin carcinogenesis, and IKKα deletion in keratinocytes causes spontaneous skin SCCs, but not BCCs, in mice. Thus, IKKα emerges as a bona fide skin tumor suppressor. In this article, we will discuss the role of IKKα in skin SCC development.

Keywords: carcinogenesis, EGFR, gene mutations, IKKα, keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, squamous cell carcinoma, TGF-β

A signature phenomenon: lack of terminal differentiation in the epidermis associated with IKKα loss in mice

IKKα/IKK/NF-κB in skin development of mice

When the conserved helix-loop-helix (HLH) ubiquitous kinase (CHUK) was shown to specifically phosphorylate serines 32 and 36 of IκBα, a major NF-κB inhibitor, it was named IκB kinase α (IKKα) or IKK1 [1–3]. IκBα binds to NF-κB proteins in the cytoplasm and masks the nuclear translocation signal of NF-κB components, thereby blocking NF-κB translocation to the nucleus [4]. NF-κB refers to a group of transcription factors that regulate the expression of many genes encoding proteins which are broadly involved in immune and inflammatory responses, cell death, cell-cycle regulation, cell proliferation and cell migration. IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ (NF-κB essential modulator [NEMO]) form the IKK complex that phosphorylates IκBs [5,6]. The phosphorylation induces IκBα protein degradation through the S26 proteasome ubiquitination machinery, allowing the freed NF-κB to move to the nucleus, functioning as a transcription factor. IKKα and IKKβ contain a kinase domain, a leucine zipper (LZ), and a HLH motif, and form homodimers and heterodimers through their motifs [3,7]. The two are highly conserved serine/threonine kinases and share many kinase substrates. However, IKKβ shows a stronger kinase activity for IκBα than IKKα does. IKKγ is a regulatory subunit. Given the similarities of IKKα and IKKβ function in vitro, they were expected to have similar physiological activities.

Genetic studies have shown that mice deficient in RelA (p65, a major NF-κB component), IKKβ, or IKKγ die from a liver cell death-induced hemorrhage during embryonic development [8–13]. Depleting tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1) rescues the phenotype in these mice (TABLE 1) [8,14–17], indicating that IKKβ and IKKγ are upstream activators of p65 in the antiapoptotic TNFR-associated pathway. No defects have been reported in embryonic skin development from the p65, Ikkγ, and Ikkβ knockouts that have been rescued by depleting TNFR1. Unexpectedly, Ikkα−/− mice complete embryonic development to full-term [18–20]. Newborns look like pupa with shiny and unwrinkled skin. Owing to the severely impaired skin development, Ikkα−/− mice lose body liquid, dry quickly, and die soon after birth. Depleting TNFR1 does not affect the phenotype of Ikkα−/− mice [21]. Thus, IKKα plays a distinct role from other IKK subunits and NF-κB during embryonic skin development.

Table 1.

Skin phenotypes in IKK mice.

| Mouse genotype | Embryonic development | Rescue | Postnatal phenotypes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IKKα−/− | Die soon after birth; epidermal hyperplasia; epidermis lacking terminally differentiated keratinocytes | Tg-K14.IKKα; Tg-K14.IKKα-KA; Tg-K5.IKKα; not Tnfr−/− |

- | [18–21,23,26] |

| IKKα+/− | Normal | - | Develop two-times more papillomas and 11-times more carcinomas; LOH in IKKα+/− skin carcinomas; mutations in papillomas and carcinomas | [60] |

|

IKKαf/f × K5.Cre ♀ × K14.Cre♀ |

Germline knockout phenotypes; die soon after birth | Tg-K5.IKKα; not Tnfr−/− |

- | [23] |

|

IKKαf/f × K5.Cre♂ × K14.Cre ♂ |

Normal | Tg-K5.IKKα; Egfr+/− |

Die within 3 weeks after birth; epidermal hyperplasia | [23] |

|

IKKαf/f × K5.CreER × K15.CrePR1 × MMTV.Cre |

Normal | Epidermal hyperplasia; spontaneous skin papillomas and carcinomas | [23] | |

| Tg-K5.IKKα | Normal | - | Normal | [23] |

| Tg-Lori.IKKα | Normal | - | Normal and inhibit carcinomas and metastases induced DMBA/TPA | [28] |

| IKKα AA/AA | Normal | - | Normal | [31] |

| IKKα KA/KA | Normal | - | Unpublished | [32] |

| IKKβ−/− | Embryonic death | Tnfr−/− normal | [8,9,17] | |

|

IKKβf/f × K14.Cre |

Normal | Tnfr−/− normal | Epidermal hyperplasia; inflammation | [17] |

| Tg-K5.IKKβ | Normal | - | Epidermal hyperplasia; inflammation | [79] |

| IKKγ−/− | Embryonic death | Tnfr−/− normal | - | [10–12] |

|

IKKγf/f × K14.Cre |

Normal | Tnfr−/− normal | Epidermal hyperplasia; inflammation | [15] |

|

IKKγf/f × K14.CreER |

Normal | Tnfr−/− normal | Epidermal hyperplasia; inflammation | [15] |

: Not examined

: Female

: Male

DMBA: 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene; LOH: Loss of heterozygosity; Tg: Transgenic; TPA: 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate.

Lack of terminal differentiation as a signature phenotype in the epidermis of Ikkα−/− mice

Skin presents the largest organ in the human body, and it is composed of dermal and epidermal layers. The epidermal barrier shields the internal organs of the body. The stratified epidermis is composed of various cells, more than 90% of which are keratinocytes, and is divided into the basal and suprabasal layers [22]. The basal epidermal keratinocytes are capable of proliferating. The suprabasal epidermis includes stratum spinosum, granulosum, lucidum and corneum, and each layer represents dissimilar differentiating keratinocytes. Keratinocytes lose their nuclei and die to give rise to a skin barrier when arriving at the top epidermal layer. Thus, the barrier formation is a consequence of epidermal keratinocyte maturation. Keratinocytes express special keratins and filaments at different differentiation stages, such as keratin 5/14 (K5/14) for basal keratinocytes, Kl/10 for intermediately differentiating keratinocytes, and loricrin and filaggrin for terminally differentiating keratinocytes [22]. Because terminally differentiated keratinocytes peel off layers of skin, new keratinocytes are constantly required. Thus, maintaining skin homeostasis requires balanced differentiation and proliferation. Disrupting this balance can lead to skin diseases [23,24]. The epidermis of Ikkα−/− mice exhibits a strikingly increased thickness, which is associated with significantly increased BrdU signals, an S-phase cell cycle indicator, in both the basal and suprabasal epidermal layers [18,25]. The electron microscope shows a lack of granulosum and corneum keratinocytes in the epidermis of Ikkα,−/− mice [18]. Immunostaining demonstrates that both the Ikkα−/− basal and suprabasal epidermis express mitotic cell markers and basal epidermal markers K5/14, and that the suprabasal epidermis expresses intermediate differentiation markers K1/K10 and involucrin, but lacks terminal differentiation markers loricrin and filaggrin [18,25]. These results indicate that IKKα is essential for embryonic skin development and that the loss of terminally differentiated keratinocytes is a signature phenotype in the epidermis of IKKα−/− mice.

IKKα is a master regulator for keratinocyte terminal differentiation & proliferation

Mouse models

Sil and colleagues have shown that transgenic IKKα driven by a K14 promoter rescues the epidermal phenotype in Ikkα−/−/Kl4-IKKα. mice [26]. Subsequently, Liu et al. demonstrated that transgenic IKKα produced from the K5 promoter also rescues the epidermal phenotype in Ikkα−/−/K5.IKKα mice [23]. However, transgenic IKKα driven by a truncated loricrin promoter, which is active at a low level in the basal and supra-basal epidermis at a later stage of embryonic development, fails to rescue Ikkα−/− mice [27,28]. Therefore, early expression of IKKα is required for epidermal formation during embryonic development. Furthermore, a nonphosphorylated IκBα, mutated at serines 32 and 36 (mlκBα) and overexpressed in the basal epidermis, affects skin homeostasis and induces skin tumors [29,30]. IκBα is the major substrate of IKKα kinase [2]. Thus, if IKKα function in skin development requires phosphorylation of IκBα, kinase-inactive IKKα should mimic the phenotype of mice overexpressing mlκBα. Sil et al. rescued the epidermal phenotype of Ikkα−/− mice using transgenic kinase-inactive IKKα [26]. Both knock-in mice expressing kinase-inactive IKKα mutated at serine 178 and 180 within the kinase ATP-activating loop (Ikkα.AA/AA), or mutated at lysine 44, an ATP-binding site (IkkαAA/AA), developed normal skin [31,32]. Therefore, IKKα kinase is not essential for embryonic skin development. These results indicate that the function of IKKα in skin development is independent of NF-κB. Furthermore, depleting TNFR rescues the skin phenotypes of transgenic mlκBα mice, but does not rescue the skin phenotypes (IKKα−/− mice and IkkαF/F/K5. Cre mice. Thus, IκBα is not an IKKα target in regulating skin development [20,23,33].

Cell culture system

It has been reported that there is a Ca2+ gradient from the basal layer to the top terminally differentiating epidermis [34]. Cultured keratinocytes mimic the journey of keratinocyte differentiation in the epidermis [35]; they undergo spontaneous terminal differentiation and the enlarged keratinocytes peeling off from keratinocyte colonies express terminal differentiation markers. Ca2+ induces wild-type (WT) keratinocytes to undergo terminal differentiation, however, primary cultured Ikkα−/− keratinocytes fail to undergo terminal differentiation and fail to respond to Ca2+-induced terminal differentiation [25,36–38]. There are no enlarged terminally differentiating keratinocytes in IKKα-null cultures; IKKα−/− keratinocytes form larger cell colonies than WT keratinocytes do [25]. Keratinocytes isolated from IkkαF/F/K5.Cre mice act as Ikkα−/− keratinocytes in culture [23]. Reintroduction of WT or kinase-inactive IKKα can induce terminal differentiation in Ikkα−/− keratinocytes, but IKKα mutants with mutations in the LZ or HLH motif, IKKβ, IκBα and/or p65 do not induce terminal differentiation [25]. The LZ or HLH motifs have been shown to be required for the formation of IKKα and IKKβ homodimer and heterodimers [7]. IKKβ is irrelevant to keratinocyte terminal differentiation, whereas mutations in the LZ or HLH of IKKα inactivate the function of IKKα in regulating keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation [23,25]. Thus, the IKKα homodimers may be essential for IKKα function in the formation of the epidermis. In addition, a mutant IKKα that is not able to move to the nucleus fails to induce Ikkα−/− keratinocytes to undergo terminal differentiation [26]. IKKα is found in the nucleus of differentiated keratinocytes and shows a nuclear localization in the normal epidermis of humans and mice [28,39,40]. These results indicate that nuclear IKKα homodimers regulate epidermal development, keratinocyte differentiation, and Ca2+-induced cell differentiation.

Terminally differentiating epidermal keratinocytes produce increased keratin, filaments and other special barrier proteins that build up the skin barrier. Thus, terminally differentiating keratinocytes and undifferentiated keratinocytes are different in many aspects, such as cellular components and morphology. The gene expression profile from cultured keratinocytes shows that IKKα-null keratinocytes lack a group of claudin tight junction proteins that are required to form tissue barriers, compared with WT cultured keratinocytes [23]. Furthermore, repeated epilation (Er) mice, which carry a mutation in the C-terminal region of the 14–3–3σ gene [41,42], develop an epidermis lacking terminally differentiating keratinocytes (FIGURE 1) [43]. Reintroduction of IKKα does not induce filaggrin expression and terminal differentiation in cultured Er keratinocytes (FIGURE 1). This indicates that the IKKα-induced filaggrin and loricrin are a consequence of the keratinocyte differentiation process, whereas IKKα does not directly regulate the expression of these terminal differentiation markers. Therefore, nuclear IKKα acts as a master regulator controlling a cascade of genes activated during the maturation process of keratinocytes, leading to the formation of the epidermis. In addition, our unpublished data show that, although primary cultured keratinocytes isolated from both Ikkα−/− and Er mice are not able to undergo terminal differentiation, Ikkα−/− keratinocytes form larger cell colonies than Er keratinocytes do. This suggests that IKKα possesses the additional activity of regulating keratinocyte proliferation compared with Er keratinoytes.

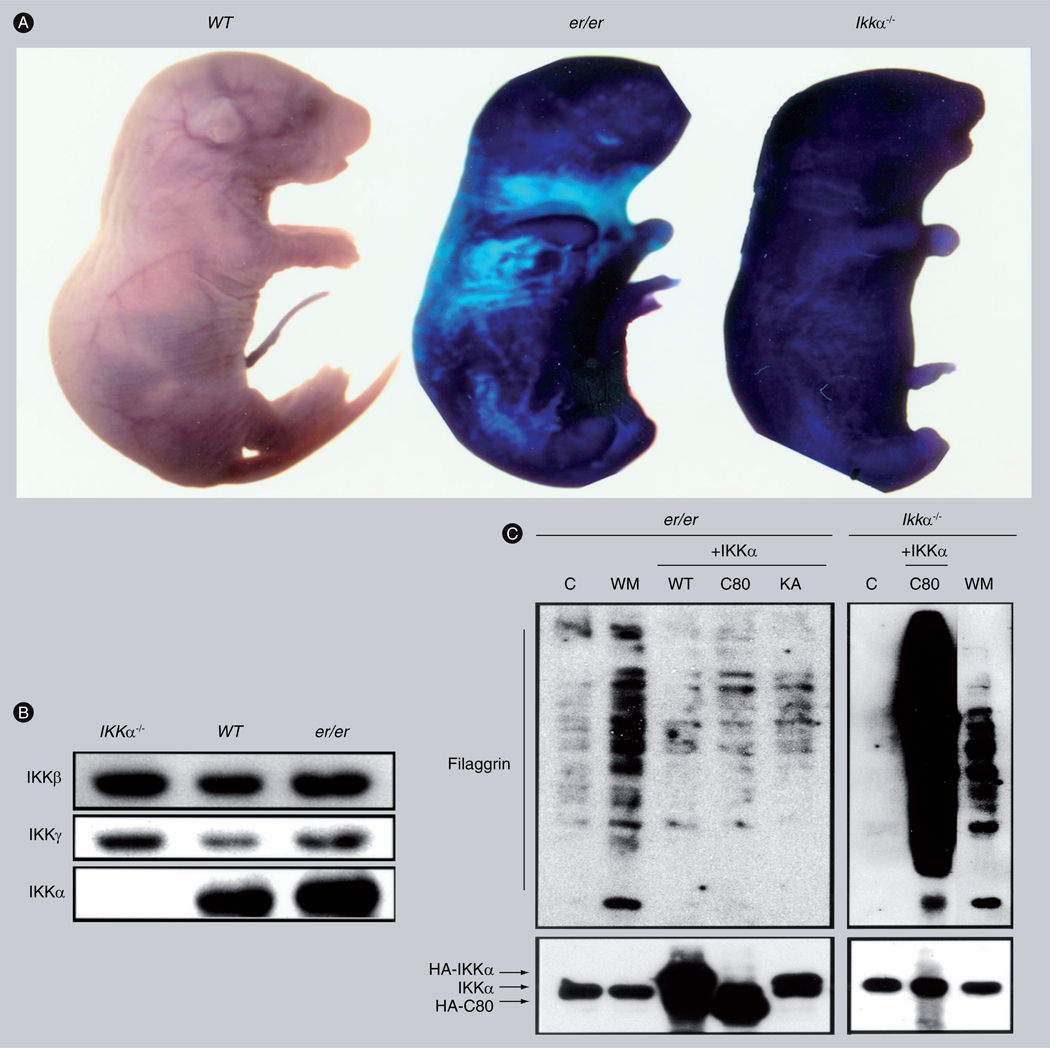

Figure 1. Keratinocytes isolated from Er (er/er) mice lack terminal differentiation marker filaggrin but express IKKα.

(A) Photos of WT, Er (er/er) and Ikkα−/− newborns stained with toluidine blue. The result indicates that the impaired skin of er/er and Ikkα−/− mice is not able to prevent water penetration. (B) Western blot compares expression of IKKβ, IKKγ and IKKα in the skin of Ikkα−/−, WT and er/er newborn mice. (C) Western blot compares terminal differentiation marker filaggrin levels in cultured er/er and Ikkα−/− keratinocytes.

+IKKα: Overexpressed HA tagged IKKα (HA-IKKα) including WT, C-terminal 80-aminal acid deletion (C80); C: Control; KA: Kinase-inactive forms; WM: WT-keratinocyte culture medium (kDIF); WT: Wild-type.

Reproduced from [24].

Although cell autonomic driving forces, such as the overexpression of Ras in the basal or suprabasal epidermis, are able to prevent cell differentiation or reverse differentiating keratinocytes to proliferating status [44,45], microenvironment is another important element influencing skin homeostasis, and skin disease development. We have shown that the growth medium from cultured WT keratinocytes, but not from Ikkα−/− keratinocytes, can induce Ikkα−/− keratinocytes to undergo terminal differentiation [25]. The diffusible protein molecule in the conditional medium is termed keratinocyte differentiation inducible factor (kDIF) [25]. It appears that differentiating keratinocytes may function to maintain a differentiation-inducing environment that contributes to skin homeostasis.

Evidence: IKKα deficiency is associated with the development of human squamous cell carcinomas

Skin squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and basal cell carcinomas are two major skin tumors derived from keratinocytes. Basal cell carcinomas rarely metastasize. Skin SCCs can progress to a highly aggressive cancer, metastasize to other organs and cause death. The epithelial cells expressing basal keratins are able to develop SCCs in many organs of humans and mice. These SCCs show a structure similar to the stratified epidermis, containing basal cells and suprabasal cells; they express basal and intermediate differentiation markers, and some even express terminal differentiation markers. The differentiation markers are lost with tumor progression. Thus, the amount of dedifferentiation is generally associated with the degree of severity of SCCs.

The human Ikkα gene is located at 10q24.31. Gene deletions or loss of heterozygosity within the 10q22–10q26 region have been frequently reported in human cancers [46]. The National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Genome Anatomy Project has revealed chromosomal deletion at this position in SCCs of the nasal and oral cavities, larynx, lung and vagina [101]. Mutations of Ikkα have been frequently identified in several types of human cancer [47]. By sequencing, we identified heterozygous point mutations and deletions in the exon 15 of the Ikkα gene from human skin SCCs. [28]. These nucleotide substitutions cause missense and nonsense mutations, and deletions cause frameshifts. Some mutations, detected from several tumors, may represent hot spots. We also examined 114 human skin SCCs using immunohistochemical staining and found that a proportion of poorly differentiated human skin SCCs expressed significantly reduced IKKα [28].

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common neoplasm of the oral cavity. The loss of epithelial phenotypes in the process of carcinoma progression correlates with clinical outcome. Maeda et al. [48] demonstrated that IKKα is expressed in the nucleus of the basal cells of normal oral epithelium, but is not detected or marginally detected in 32.8% of carcinomas. IKKα immunoreactivity significantly decreased in poorly differentiated carcinomas (p <0.05) and conversely correlated with the long-term survival of patients (p <0.01). Four out of 64 patients showed allelic/biallelic loss of Ikkα and 63% of the patients had microsatellite instability and a hypermethylated Ikkα promoter. These results suggest that oral carcinomas exhibiting genetic instability and promoter hypermethylation downregulate the expression of IKKα, which is associated with disease progression toward an unfavorable prognosis.

Marinari et al. have also found that IKKα nuclear staining is strongly reduced in tumors versus the normal epithelium in 245 skin, pharynx, esophagus and lung SCCs, and in 39 controls [40]. IKKα is downregulated in 78% of skin SCCs and in 82% of SCCs derived from other stratified epithelia such as lung, esophagus and oral cavity/larynx. The amount of IKKα correlates with clinical stage, is highest in well-differentiated tumors and lowest in high-grade, poorly differentiated primary SCCs. In the SCCs with little nuclear staining, cytoplasmic IKKα was frequently observed. Furthermore, Marinari et al. demonstrate that nuclear IKKα is progressively lost at the boundary zone of the hyperplastic/dysplastic epidermis (actinic keratose), and that, in situ, SCCs convert to invasive SCCs, suggesting that IKKα down-regulation and relocalization are associated with tumor progression [40]. Descargues et al. demonstrated a nuclear expression pattern of IKKα in normal human epidermal cells [39]. In addition, Marinari et al. [40] and Moreno-Maldonado et al. [49] consistently show that IKKα induces differentiation in human HaCaT keratinocytes, and demonstrate a close relationship between IKKα levels and histological variants of human epidermal SCCs.

In summary, IKKα is mainly localized in the nucleus of normal epidermal keratinocytes but moves to the cytoplasm in SCCs. Downregulation of IKKα is associated with human SCC dedifferentiation and progression, and genomic instability, but is conversely associated with the prognosis of this disease. These associations highlight the critical role that IKKα plays in suppressing the development of human SCCs and reveal that the Ikkα gene is a target during skin tumorigenesis. This suggests that IKKα deficiency may be a critical driving force in SCC development.

Mouse models exhibit IKKα as a bona fide skin tumor suppressor

Chemical and ultraviolet B (UVB) carcinogenesis are the two most popular mouse models used to study tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis in the skin. In the classical two-stage chemical carcinogenesis protocol, chemical carcinogen 7,12-dimethylbenz(α) anthracene (DMBA) activates oncogenic H-Ras by inducing Ras-activating mutations (V61, CAA→CTA; V12, GGA→GGC) and tumor promoter 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) expands the Ras-initiated cells [50–53]. Overexpressed active Ras promotes cell proliferation and transformation and prevents keratinocytes from undergoing terminal differentiation [54]. UVB is a carcinogen that can mutate the tumor suppressor gene p53 at an early stage of UVB carcinogenesis and causes inflammation and suppression of normal immune function [55]. UVB also induces cell death and cell cycle arrest, which limit UVB-induced damage. Both DMBA/TPA and UVB induce papillomas and carcinomas that resemble human SCCs. Most human SCCs contain p53 mutations and increased Ras activity [56–58]. Skin cells can carry p53 mutations for many years before the onset of skin cancer. Caulin et al. demonstrate that p53 mutation and K-rasG12D cooperate to initiate skin tumors, and to promote progression and metastasis [59]. Thus, the two pathways are relevant to human skin cancer.

Chemical carcinogenesis

We have shown that Ikkα+/− mice develop twice as many papillomas and 11-times as many carcinomas than Ikkα+/+ mice in a DMBA/TPA-induced carcinogenesis setting [60]. Most Ikkα+/−carcinomas and half of the Ikkα+/− papillomas show loss of heterozygosity of Ikkα and express reduced levels of IKKα. Thus, IKKα loss promotes tumor progression. The carcinomas derived from Ikkα+/− mice are poorly differentiated, indicating a correlation between IKKα loss and the expansion of poorly differentiated tumor cells in SCCs. Furthermore, random mutations in the Ikkα gene were detected in papillomas and carcinomas developed from both Ikkα+/− and Ikkα+/+ mice [60]. We found that increased levels of mutations in IKKα isolated from DMBA/TPA-induced skin tumors correlated with the loss of IKKα’s ability to induce keratinocyte terminal differentiation in culture [23]. These results suggest that the Ikkα gene is a relevant target of chemical carcinogens and that IKKα function is important for preventing skin tumors. IKKα reduction also promotes TPA-induced angiogenic and ERK activity, and this increases TPA-induced TNF-α, IL-1, EGF, heparin-binding EGF (HB-EGF), amphiregulin (AR), and VEGF-A levels in the skin [60]. Interestingly, increased IKK kinase activity is observed in carcinomas that have lost IKKα. Whether increased IKK activity contributes to tumor progression remains to be tested. In addition, we observed a reduction of 14–3–3σ levels, a G2/M cell cycle checkpoint in response to DNA damage, and nucleophosmin, which is important for genomic stability in carcinomas compared with papillomas [32,61–64]. Overall, IKKα reduction provides a growth advantage in conjunction with Ras activity and also promotes the expression of various cytokines, angiogenesis and genomic instability during skin carcinogenesis.

On the other hand, transgenic Lori.IKKα mice develop fewer malignant carcinomas and metastases compared with WT mice in a DMBA/TPA-induced carcinogenesis setting [28]. Interestingly, the endogenous IKKα levels are higher in carcinomas developed from Lori.IKKα mice than in carcinomas developed from WT mice. In addition, we found that overexpressed IKKα represses TPA- and Ras-induced VEGF-A expression by regulating their promoter activity in keratinocytes, and that it promotes TPA-induced terminal differentiation in the skin. Thus, IKKα affects the microenvironment surrounding tumor sites, which regulates tumor development in mice.

Ultraviolet B carcinogenesis

Ultraviolet B induces twice as many skin tumors in Ikkα+/− than in Ikkα+/+ mice [65]. The tumor latency is significantly shorter and tumors are much larger in Ikkα+/− than in Ikkα+/+ mice. UVB-induced signature p53 mutations at the early initiation stage increase dramatically in Ikkα+/− skin, but UVB-induced cell death is significantly reduced in Ikkα+/−skin compared with Ikkα+/+ skin. In addition, NF-κB DNA-binding and ERK activity, TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, MCP-1/CCL2 levels and infiltrating macrophages increase in Ikkα+/− compared with Ikkα+/+ skin following UVB treatment. The increased NF-κB activity and p53 mutations may contribute to decreased apoptosis. Therefore, IKKα reduction promotes UVB carcinogenesis via multiple mechanisms.

Spontaneous skin tumors in mice lacking IKKα in keratinocytes

The Ikkα floxed mice with IKKα deletion using K5.Cre (IkkαF/F/K5.Cre) develop epidermal hyperplasia and die within 3 weeks of birth [23]. Inducible IKKα deletion causes epidermal hyperplasia and spontaneous skin papillomas and carcinomas in adult IkkαF/F/K5.CreER and IkkαF/F/K15.CrePR1 mice. We have found elevations in EGFR and ERK activity, EGF and HB-EGF levels and the expression of ADAM sheddases (e.g., ADAM9, 10, 12, 17 and 19) that cleave EGF and HB-EGF precursors to generate their active soluble forms [66], in the IKKα-null epidermis in comparison with the WT epidermis [23]. These molecules can be activated in an autocrine loop of EGFR/ERK/EGF/HB-EGF/ADAM signaling. Thus, reintroduction of IKKα, and the inactivation of EGFR, and/or EGFR inhibitors, blocks IKKα loss-induced epidermal hyperproliferation and skin tumors in mice. Interestingly, depleting TNFR1 does not affect the phenotype of epidermal hyperplasia in IkkαF/F/K5. Cre mice (although we did not test whether depleting TNFR1 affects IKKα deletion-induced skin tumors) [23]. Therefore, EGFR signaling is crucial for IKKα-associated skin homeostasis and skin tumor development.

Mechanism of IKKα-induced keratinocyte differentiation & suppression of skin tumor development

The observation that IKKα deficiency is a driving force in skin tumor development in animal models is fully supported by the observed association of IKKα deficiency with human SCC occurrence. During skin tumorigenesis, IKKα deficiency induces keratinocyte dedifferentiation, increased proliferation, angiogenesis, inflammation, metalloproteinase expression, increased mutagenesis and reduced apoptosis. Several reports have investigated the mechanism by which IKKα regulates keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation. Since SCC is a type of malignancy closely associated with changes in tumor cell differentiation and proliferation, we focus on discussing these issues below.

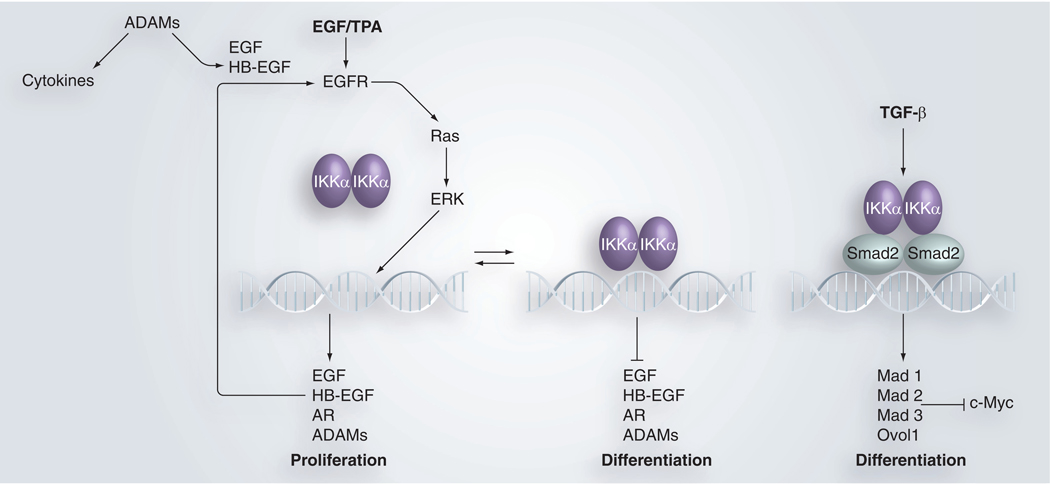

A loop of EGF receptor/Ras/ERK/EGF receptor ligands

Oncogenic H-Ras antagonizes Ca++-induced terminal differentiation and promotes keratinocyte proliferation and transformation [67]. DMBA initiates skin tumors by inducing activating H-Ras mutations [44]. EGFR signaling is upstream of Ras and leads to the activation of ERK and the transcription of genes encoding proteins that regulate cell proliferation. Reduction of EGFR restores keratinocyte differentiation in keratinocytes overexpressing Ras [68]. EGFR is frequently activated in human SCCs [69]. Thus, the EGFR/Ras pathway is important for keratinocyte differentiation, regulation of proliferation and skin tumor development. We have demonstrated that IKKα loss elevates Ras, EGFR and ERK activity, as well as EGF and HB-EGF levels, in keratinocytes, indicating that IKKα represses this loop of EGFR/Ras/ERK/EGFR ligands. The introduction of IKKα, a dominant negative form of RasN17, EGFR inhibitor and/or ERK inhibitor reduces Ras, EGFR, ERK activities and growth factor levels, while also repressing cell proliferation and inducing terminal differentiation in IKKα-null keratinocytes [23]. Thus, IKKα regulates keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation via the EGFR/Ras/ERK/EGFR-ligand loop (FIGURE 2). We used the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay to demonstrate that IKKα binds to the promoter regions of EGF, HB-EGF, AR and ADAMs, and that these binding levels correlated with the decreased expression of corresponding molecules [23]. Treatment with EGF or TPA reduces IKKα binding to these promoters and elevates expression of these genes. Increased mutation levels in Ikkα reduce IKKα binding to the EGF promoter, which correlates with elevated EGF expression in keratinocytes. Thus, nuclear IKKα activity suppresses expression of EGF, HB-EGF and AR (FIGURE 2). The loss of IKKα increases the expression of EGFR ligands, resulting in excessive EGFR, Ras and ERK activation. As previously mentioned, inactivating EGFR induces differentiation, represses proliferation and prevents skin tumors in mice lacking IKKα in the epidermis. The nuclear function of IKKα in regulating the EGFR-mediated loop is consistent with the observed IKKα nuclear localization in normal epidermal keratinocytes [39,40,48]. In addition, treatment with TPA or EGF reduces the binding of IKKα to the promoters of growth factors and elevates the expression of these growth factor genes, indicating that IKKα represses the EGFR/Ras/ERK loop via the suppression of the transcription of genes that encode the EGFR ligands (EGF and HB-EGF). These results suggest that increasing nuclear IKKα levels may compensate for the activity of TPA or EGF in reducing IKKα binding to the promoters of genes encoding growth factors, thereby preventing amplified EGFR/Ras/ERK activity and cell proliferation but maintaining the status of cell differentiation, as we have shown that overexpression of IKKα in the epidermis inhibits carcinogen-induced skin carcinogenesis in mice [28]. On the other hand, the IKKα found in the cytoplasm of SCCs [40] may have a different function. We have also observed increased levels of IKKα in the cytoplasm in some human SCCs [LIU AND HU, 2010, UNPUBLISHED DATA]. In addition, we previously demonstrated that transformed IKKα-null keratinocytes were not able to respond to an IKKα-mediated differentiation signal [38]. Therefore, the altered IKKα (even elevated IKKα levels) may lose its normal function in those tumor cells.

Figure 2. Nuclear IKKα function in regulating keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation.

Arrows indicate positive directions and lines present the inhibitory effect. DNA symbols represent promoter regions of genes. EGF/TPA and TGF-β in bold represent exogenous stimuli for cells.

ADAM: A disintegrin and metalloprotease; TPA: 12-0-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate.

TGF-β/c-Myc pathway

TGF-β acts as a tumor suppressor at the early stage of tumor development and affects cell proliferation, differentiation and inflammation [70]. c-Myc, a transcription factor, forms dimers with Max (c-Myc/Max) in order to regulate gene transcription [71]. Many targets of c-Myc are crucial for keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation in the skin, and these molecules crosstalk with TGF-β signaling via Smads [72]. Max dimer protein 1 (Mad1) and its relatives, including Mad2, Mad3, Mad4 and Ovo-like 1 (Ovol1) can also form heterodimers with Max (Max/Mad). The Max/Mad dimers compete with c-Myc/Max dimers for the consensus elements on the promoters of c-Myc’s targets [71]. Thus, Mad proteins antagonize the c-Myc/Max dimer-induced function in regulating cell differentiation and proliferation [71,73,74]. Descargues et al. [39] and Marinari et al. [40] have shown that IKKα forms a complex with Smad2 or Smad3 on the promoters of Mad genes following treatment with TGF-β. IKKα loss downregulates Mad1, Mad2, Mad3, Mad4 and Ovol1 expression and elevates c-Myc activity in keratinocytes. Therefore, IKKα plays an important role in mediating TGF-β signaling to antagonize c-Myc activity (FIGURE 2). Excessive c-Myc activity prevents cell cycle exit, thereby preventing cell differentiation [75]. By contrast, Mad1 and Ovol1 are associated with cell differentiation [71]. Descargues et al. [39] and Marinari et al. [40] further show that TGF-β-induced keratinocyte differentiation requires IKKα via Smad2 or Smad3. IKKα loss results in a failure to mediate TGF-β-led differentiation signaling in keratinocytes, but instead elevates c-Myc activity, which contributes to the promotion of cell proliferation. In addition, the G1/S cell cycle checkpoint, p21, is a TGF-β-induced gene [40]. Again, IKKα-null keratinocytes fail to induce the expression of p21 following TGF-β stimulation, suggesting that IKKα-null keratinocytes are not able to respond to TGF-β-mediated cell cycle arrest and cell differentiation. In the SCC environment, TGF-β is elevated, however, TGF-β may fail to exert its tumor suppressor activity in tumor cells lacking IKKα or expressing mutated IKKα, owing to the fact that Ikkα is a major target of mutagenesis in tumorigenesis. Thus, IKKα is crucial for TGF-β-induced tumor suppressor activity during skin tumorigenesis.

Microenvironment: differentiation/inflammation/angiogenesis

The nuclear IKKα mediates two intrinsic pathways: the suppression of EGFR/Ras/ERK/EGFR-ligand loop and the promotion of TGF-β-mediated c-Myc antagonists in regulating keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation. At skin lesion sites, keratinocytes, dermal cells and infiltrating leukocytes produce many growth factors, cytokines and chemokines. IKKα provides a surveillance function to limit the impact of these molecules on skin homeostasis. In addition, IKKα directs the production of kDIF, maintaining an environment that induces cells to differentiate. IKKα represses VEGF-A expression, inhibiting the formation of tumor promoter-induced micro-blood vessels. IKKα downregulates the metalloprotein ADAMs that activate various growth factors and cytokines (FIGURE 2). However, IKKα reduction or loss removes these protections, further amplifying these responses in a loop and eventually cause skin diseases.

Future perspective

Tumor development requires progression through multiple stages via distinct mechanisms. In the future, it will therefore be important to determine the specific cell types that initiate tumors in the absence of IKKα. As stem cells are likely to be the targets, it is necessary to verify these targets and further determine whether the molecular events that alter stem cell-related genes contribute to the maintenance of the properties of the progenitor cells that prevent keratinocyte differentiation and promote cell proliferation in the absence of IKKα. We have not identified the crucial mechanisms by which IKKα loss promotes tumor progression or how genomic instability affects the neoplastic transformation of tumor-initiating keratinocytes [60]. We also do not know how nuclear IKKα regulates gene transcription in detail. We have observed elevated IKK activity in those carcinomas [60]; however, whether IKK activity promotes tumor progression remains to be tested. If IKK activity is important for tumor progression, we will need to determine why IKK activity is elevated in carcinomas and how IKKα reduction elevates the expression of cytokines. In addition, tumor development is subject to immune surveillance in vivo. We still need to determine the effect of IKKα-associated immune responses on skin inflammation and tumor development. IKKα deficiency has been detected in SCCs from different organs in humans. Thus, it is important to determine whether IKKα deficiency is involved in other types of SCCs in mice. Together, these studies will not only provide the mechanisms of IKKα-associated tumor development, but also provide new insight into therapeutic targets for preventing and treating skin cancer.

In addition, although this review mainly discusses skin SCCs, Greenman et al. also found the mutations of IKKα, (CHUK) in 210 diverse human cancers including breast, colorectal, gastric, glioma, lung, ovarian, renal, melanoma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (TABLE 2) [47]. A new study demonstrates that the human lethal syndrome with multiple fetal malformations similar to those observed in Ikkα−/− mice is linked to a point mutation in the Ikkα gene that leads to the loss of IKKα (CHUK) in two affected fetuses [76]. This is the first report for IKKα associated with human genetic (autosomal recessive) disease. On the other hand, IKKα has been suggested as a tumor promoter [77,78]. Thus, whether IKKα functions differently in different types of tumors and in other human diseases remains to be determined.

Table 2.

Mutations in IKKα (CHUK) identified from human cancer.

| Sample | Count | cDNA annotation | Protein change | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast C | 1 | 717A>G | P239P | Silent |

| Ovarian C | 1 | 376A>T | S126C | Missense |

| Multiple | 3 | 1503G>A | G501G | Silent |

| Multiple | 4 | 1341A>G | G447G | Silent |

| Multiple | 6 | 464T>C | V155A | Missense |

| Multiple | 9 | 148C>T | L50L | Silent |

| Multiple | 17 | 1458C>T | S486S | Silent |

| Multiple | 105 | 802G>A | V268I | Missense |

Results obtained from examining 518 protein kinase genes in 210 diverse human cancers including acute lymphoblastic leukemia, breast, colorectal, gastric, glioma, lung, ovarian, renal and melanoma. C: Cancer.

Data taken from [47].

Executive summary.

IKKα loss causes epidermal hyperplasia during mouse embryonic development

Ikkα−/− newborn mice are malformed and die soon after birth,

IKKα−/− epidermis lacks terminally differentiated keratinocytes

Body liquid of IKKα−/− newborn mice is lost very quickly owing to impaired epidermis formation.

IKKα is a master regulator for keratinocyte terminal differentiation & proliferation

Cultured wild-type (WT) keratinocytes spontaneously undergo terminal differentiation.

Cultured IKKα-null keratinocytes are not able to undergo terminal differentiation, instead, they continuously proliferate. Thus, IKKα-null keratinocytes form larger cell colonies than WT keratinocytes do.

Altered IKKα localization, downregulated IKKα & Ikkα mutations & deletions are reported in multitypes of human squamous cell carcinomas

Mouse squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) resemble human SCCs.

Elevated IKKα level in the epidermis inhibits development of skin carcinomas & metastases induced by chemical carcinogens in mice

IKKα antagonizes chemical carcinogen-induced mitogenic and angiogenic activities, and represses tumor progression and metastases during skin carcinogenesis in mice.

IKKα reduction promotes chemical carcinogen- or ultraviolet B-induced skin carcinogenesis in mice

Ikkα+/− mice develop two-times more papillomas and 11-times more carcinomas than Ikkα+/+ mice do in DMBA/TPA-induced skin carcinogenesis.

Most of the Ikkα+/+ carcinomas and half of the Ikkα+/− papillomas lose the remaining WT allele of Ikkα.

Ikkα mutations are detected in DMBA/TPA-induced papillomas and carcinomas.

Ikkα+/− mice develop two-times more skin tumors than Ikkα+/+do in ultraviolet B-induced skin carcinogenesis.

Ultraviolet B irradiation induces more p53 mutations and fewer apoptotic cells in Ikkα+/− skin than in Ikkα+/+ skin.

IKKα deletion in keratinocytes induces spontaneous skin papillomas & carcinomas

IKKα deletion elevates EGFR, Ras and ERK activity and elevates levels of EGF, HB-EGF, AR and ADAMs.

IKKα represses transcription of genes encoding EGF, HB-EFG, AR and ADAMs in keratinocytes.

Reintroduction of IKKα or dominant negative RasN17 represses IKKα-null keratinocyte proliferation and induces keratinocytes to terminal differentiation.

Reintroduction of IKKα, or inactivation of EGFR, prevents skin tumor development.

IKKα induces Mad1, Mad2, Ovol1 and c-Myc antagonists through TGF-β-mediated Smad2/3 pathway in regulation of keratinocyte differentiation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Susan M Fischer for her involvement, support, and collaboration in these studies; Michael Karin for supporting the research on mouse embryonic skin development (Yinling Hu’s postdoc’ work); and Stephen Anderson for editing this review.

Footnotes

Financial & competing Interests disclosure

National Cancer Institute grants CA102510 and CA117314 (to Yinling Hu), CA105345 (to Susan M Fischer), and the National Cancer Institute intramural budget supported, the work. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

■ of interest

■■ of considerable interest

- 1.Mock BA, Connelly MA, McBride OW, Kozak CA, Marcu KB: CHUK, a conserved helix-lo op-helix ubiquitous kinase, maps to human chromosome 10 and mouse chromosome 19. Genomics 27,348–351 (1995).■ Identifies the human conserved helix-loop-helix ubiquitous kinase (CHUK), IκBα kinase α (IKKα).

- 2.DiDonato JA, Hayakawa M, Rothwarf DM, Zandi E, Karin M: A cytokine-responsive IκB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-κB. Nature 388, 548–554 (1997).■ Identifies that IKKα phosphorylates IκBs.

- 3.Mercurio F, Zhu H, Murray BW et al. : IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IκB kinases essential for NF-κB activation. Science 278, 860–866 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothwarf DM, Karin M: The NF-κB activation pathway: a paradigm in information transfer from membrane to nucleus. Sci. STKE 1999, RE1 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y: Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-κB activity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 621–663 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh S, Karin M: Missing pieces in the NF-κB puzzle. Cell 109(Suppl.) S81–S96 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zandi E, Rothwarf DM, Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Karin M: The IκB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKα and IKKβ, necessary for IκB phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. Cell 91, 243–252 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Q, Van Antwerp D, Mercurio F, Lee KF, Verma IM: Severe liver degeneration in mice lacking the IκB kinase 2 gene. Science 284, 321–325 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li ZW, Chu W, Hu Yet al.: The IKKβ subunit of IκB kinase (IKK) is essential for nuclear factor κB activation and prevention of apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 189, 1839–1845 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makris C, Godfrey VL, Krahn-Senftleben G et al. : Female mice heterozygous for IKKγ/ NEMO deficiencies develop a dermatopathy similar to the human X-linked disorder incontinentia pigmenti. Mol. Cell5, 969–979 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudolph D, Yeh WC, Wakeham A et al. : Severe liver degeneration and lack of NF-κB activation in NEMO/IKKγ-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 14, 854–862 (2000). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt-Supprian M, Bloch W, Courtois G et al. : NEMO/IKKγ-deficient mice model incontinentia pigmenti. Mol. Cell 5, 981–992 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beg AA, Sha WC, Bronson RT, Ghosh S, Baltimore D: Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-κB. Nature 376, 167–170 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alcamo E, Mizgerd JP, Horwitz BH et al. : Targeted mutation of TNF receptor I rescues the RelA-deficient mouse and reveals a critical role for NF-κB in leukocyte recruitment. J. Immunol. 167, 1592–1600 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nenci A, Huth M, Funteh A et al. : Skin lesion development in a mouse model of incontinentia pigmenti is triggered by NEMO deficiency in epidermal keratinocytes and requires TNF signaling. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 531–542 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doi TS, Marino MW, Takahashi T et al. : Absence of tumor necrosis factor rescues RelA-deficient mice from embryonic lethality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 2994–2999 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasparakis M, Courtois G, Hafner M et al. : TNF-mediated inflammatory skin disease in mice with epidermis-specific deletion of IKK2. Nature 417, 861–866 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu Y, Baud V, Delhase M et al. : Abnormal morphogenesis but intact IKK activation in mice lacking the IKKα subunit of IκB kinase. Science 284, 316–320 (1999).■■ Demonstrates that IKKα is required for the formation of the epidermis during mouse embryonic development.

- 19.Take da K, Takeuchi O, Tsujimura T et al. : Limb and skin abnormalities in mice lacking IKKα. Science 284, 313–316 (1999).■■ Demonstrates that IKKα is required for the formation of the epidermis during mouse embryonic development.

- 20.Li Q, Lu Q, Hwang JY et al. : IKK1-deficient mice exhibit abnormal development of skin and skeleton. Genes Dev. 13, 1322–1328 (1999).■■ Demonstrates that IKKα is required for the formation of the epidermis during mouse embryonic development.

- 21.Li Q, Estepa G, Memet S, Israel A, Verma IM: Complete lack of NF-κB activity in IKK1 and IKK2 double-deficient mice: additional defect in neurulation. Genes Dev. 14, 1729–1733 (2000). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuchs E, Byrne C: The epidermis: rising to the surface. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 4, 725–736 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu B, Xia X, Zhu F et al. : IKKα is required to maintain skin homeostasis and prevent skin cancer. Cancer Cell 14, 212–225 (2008).■■ Demonstrates that IKKα deletion in keratinocytes causes spontaneous skin tumors in mice.

- 24.Zenz R, Scheuch H, Martin P et al. : c-Jun regulates eyelid closure and skin tumor development through EGFR signaling. Dev. Cell. 4, 879–889 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu Y, Baud V, Oga T, Kim KI, Yoshida K, Karin M: IKKα controls formation of the epidermis independently of NF-κB. Nature 410,710–714 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sil AK, Maeda S, Sano Y, Roop DR, Karin M: IKKα acts in the epidermis to control skeletal and craniofacial morphogenesis. Nature 428, 660–664 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiSepio D, Bickenbach JR, Longley MA, Bundman DS, Rothnagel JA, Roop DR: Characterization of loricrin regulation in vitro and in transgenic mice. Differentiation 64, 225–235 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu B, Park E, Zhu F et al. : A critical role for IκB kinase α in the development of human and mouse squamous cell carcinomas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 17202–17207 (2006).■■ Ikkα mutations and downregulated IKKα are identified in human squamous cell carcinomas and elevated IKKα inhibits skin tumor progression and metastases in mice.

- 29.van Hogerlinden M, Rozell BL, Ahrlund-Richter L, Toftgard R: Squamous cell carcinomas and increased apoptosis in skin with inhibited Rel/nuclear factor-kB signaling. Cancer Res. 59, 3299–3303 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seitz CS, Lin Q, Deng H, Khavari PA: Alterations in NF-κB function in transgenic epithelial tissue demonstrate a growth inhibitory role for NF-κB. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 2307–2312 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao Y, Bonizzi G, Seagroves TN et al. : IKKα provides an essential link between RANK signaling and cyclin Dl expression during mammary gland development. Cell 107, 763–775 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu F, Xia X, Liu B et al. : IKKα shields 14–13–3σ, a G(2)/M cell cycle checkpoint gene, from hypermethylation, preventing its silencing. Mol. Cell 27, 214–227 (2007).■■ Demonstrates that IKKα regulates the cell cycle regulation through regulating 14–13–3σ transcription in an epigenetic manner in keratinocytes.

- 33.Lind MH, Rozell B, Wallin RP et al. : Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1-mediated signaling is required for skin cancer development induced by NF-κB inhibition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101,4972–4977 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mauro T, Bench G, Sidderas-Haddad E, Feingold K, Elias P, Cullander C: Acute barrier perturbation abolishes the Ca2+ and K+ gradients in murine epidermis: quantitative measurement using PIXE.J. Invest. Dermatol. 111, 1198–1201 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun TT, Green H: Differentiation of the epidermal keratinocyte in cell culture: formation of the cornified envelope. Cell 9, 511–521 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watt FM, Green H: Stratification and terminal differentiation of cultured epidermal cells. Nature 295, 434–436 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hennings H, Michael D, Cheng C, Steinert P, Holbrook K, Yuspa SH: Calcium regulation of growth and differentiation of mouse epidermal cells in culture. Cell 19, 245–254 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu B, Zhu F, Xia X, Park E, Hu Y: A tale of terminal differentiation: IKKα, the master keratinocyte regulator. Cell Cycle 8, 527–531 (2009).■■ Demonstrates that IKKα loss promotes keratinocyte transformation.

- 39.Descargues P, Sil AK, Sano Y et al. : IKKα is a critical coregulator of a Smad4-independent TGFβ-Smad2/3 signaling pathway that controls keratinocyte differentiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 2487–2492 (2008).■■ Demonstrates that TGF-β regulates IKKα-mediated pathway in keratinocyte differentiation.

- 40.Marinari B, Moretti F, Botti E et al. : The tumor suppressor activity of IKKα in stratified epithelia is exerted in part via the TGF-β antiproliferative pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 17091–17096 (2008).■■ Demonstrates that IKKα downregulation is reported in multiple types of human SCCs and demonstrates the importance of IKKα in TGF-β-mediated pathway.

- 41.Li Q, Lu Q, Estepa G, Verma IM: Identification of 14–13–3σ mutation causing cutaneous abnormality in repeated-epilation mutant mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15977–15982 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herron BJ, Liddell RA, Parker A et al. : A mutation in stratifin is responsible for the repeated epilation (Er) phenotype in mice. Nat Genet. 37, 1210–1212 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fisher C: IKKα−/− mice share phenotype with pupoid fetus (pf/pf) and repeated epilation (Er/Er) mutant mice. Trends Genet. 16, 482–484 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balmain A, Pragnell IB: Mouse skin carcinomas induced in vivo by chemical carcinogens have a transforming Harvey-ras oncogene. Nature 303, 72–74 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenhalgh DA, Rothnagel JA, Quintanilla MI et al. : Induction of epidermal hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis, and papillomas in transgenic mice by a targeted v-Ha-ras oncogene. Mol. Carcinog. 7, 99–110 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petersen S, Rudolf J, Bockmuhl U et al. : Distinct regions of allelic imbalance on chromosome 10q22-q26 in squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. Oncogene 17, 449–454 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R et al. : Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature 446, 153–158 (2007).■■ Many Ikkα mutations are detected in different types of human cancers.

- 48.Maeda G, Chiba T, Kawashiri S, Satoh T, Imai K: Epigenetic inactivation of IκB Kinase-α in oral carcinomas and tumor progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 5041–5047 (2007).■■ Reveals the relationship of deregulated IKKα and clinical progression of human SCCs.

- 49.Moreno-Maldonado R, Ramirez A, Navarro M et al. : IKKα enhances human keratinocyte differentiation and determines the histological variant of epidermal squamous cell carcinomas. Cell Cycle 7, 2021–2029 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quintanilla M, Brown K, Ramsden M, Balmain A: Carcinogen-specific mutation and amplification of Ha-ras during mouse skin carcinogenesis. Nature 322, 78–80 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slaga TJ, O’Connell J, Rotstein J et al. : Critical genetic determinants and molecular events in multistage skin carcinogenesis. Symp. Fundam. Cancer Res. 39, 31–44 (1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kiguchi K, Beltran L, Dubowski A, DiGiovanni J: Analysis of the ability of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate to induce epidermal hyperplasia, transforming growth factor-α, and skin tumor promotion in wa-1 mice. J. Invest. Dermatol. 108, 784–791 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang XJ, Liefer KM, Greenhalgh DA, Roop DR: 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate promotion of transgenic mouse epidermis coexpressing transforming growth factor-α and v-fos: acceleration of autonomous papilloma formation and malignant conversion via c-Ha-ras activation. Mol. Carcinog. 26, 305–311 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roop DR, Lowy DR, Tambourin PE et al. : An activated Harvey ras oncogene produces benign tumours on mouse epidermal tissue. Nature 323, 822–824 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Melnikova VO, Ananthaswamy HN: Cellular and molecular events leading to the development of skin cancer. Mutat. Res. 571, 91–106 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pierceall WE, Kripke ML, Ananthaswamy HN: N-ras mutation in ultraviolet radiation-induced murine skin cancers. Cancer Res. 52, 3946–3951 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brash DE, Rudolph JA, Simon JA et al. : A role for sunlight in skin cancer: UV-induced p53 mutations in squamous cell carcinoma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 10124–10128 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ziegler A, Jonason AS, Leffell DJ et al. : Sunburn and p53 in the onset of skin cancer. Nature 372, 773–776 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caulin C, Nguyen T, Lang GA et al. : An inducible mouse model for skin cancer reveals distinct roles for gain- and loss-of-function p53 mutations. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1893–1901 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park E, Zhu F, Liu B et al. : Reduction in IκB kinase α expression promotes the development of skin papillomas and carcinomas. Cancer Res, 67, 9158–9168 (2007).■■ Demonstrates that IKKα reduction promotes tumor initiation and IKKα loss promotes tumor progression in chemical carcinogen-induced skin carcinogenesis.

- 61.Zhu F, Park E, Liu B, Xia X, Fischer SM, Hu Y Critical role of IkB kinase α in embryonic devleopment and skin carcinogenesis. Histol. Histopathol. 24, 265–271 (2009).■ Identifies targets for IKKα loss-promoted tumor progression.

- 62.Chan TA, Hermeking H, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B: 14–13–3σ is required to prevent mitotic catastrophe after DNA damage. Nature 401, 616–620 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Okuda M, Horn HF, Tarapore P et al. : Nucleophosmin/B23 is a target of CDK2/cyclin E in centrosome duplication. Cell 103, 127–140 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grisendi S, Bernardi R, Rossi M et al. : Role of nucleophosmin in embryonic development and tumorigenesis. Nature 437, 147–153 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xia X, Park E, Liu B et al. : Reduction of IKKα expression promotes chronic ultraviolet B exposure-induced skin inflammation and carcinogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 2500–2508 (2010).■■ IKKα reduction promotes ultraviolet B-induced skin carcinogenesis.

- 66.Huovila AP, Turner AJ, Pelto-Huikko M, Karkkainen I, Ortiz RM: Shedding light on ADAM metalloproteinases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30,413–422 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yuspa SH, Morgan DL: Mouse skin cells resistant to terminal differentiation associated with initiation of carcinogenesis. Nature 293, 72–74 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dlugosz AA, Hansen L, Cheng C et al. : Targeted disruption of the epidermal growth factor receptor impairs growth of squamous papillomas expressing the v-ras(Ha) oncogene but does not block in vitro keratinocyte responses to oncogenic ras. Cancer Res. 57, 3180–3188 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leong JL, Loh KS, Putti TC, Goh BC, Tan LK: Epidermal growth factor receptor in undifferentiated carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Laryngoscope 114, 153–157 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bierie B, Moses HL: Tumour microenvironment: TGFβ: the molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 506–520 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grandori C, Cowley SM, James LP, Eisenman RN: The Myc/Max/Mad network and the transcriptional control of cell behavior. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 16, 653–699 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raftery LA, Sutherland DJ: TGF-β family signal transduction in Drosophila development: from Mad to Smads. Dev. Biol. 210, 251–268 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pulverer B, Sommer A, McArthur GA, Eisenman RN, Luscher B: Analysis of Myc/Max/Mad network members in adipogenesis: inhibition of the proliferative burst and differentiation by ectopically expressed Mad1. J. Cell. Physiol. 183, 399–410 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Teng A, Nair M, Wells J, Segre JA, Dai X: Strain-dependent perinatal lethality of Ovol1-deficient mice and identification of Ovol2 as a downstream target of Ovol1 in skin epidermis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1772, 89–95 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gandarillas A, Watt FM: c-Myc promotes differentiation of human epidermal stem cells. Genes Dev. 11,2869–2882 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lahtela J, Nousiainen HO, Stefanovic V et al. : Mutant CHUK and severe fetal encasement malformation. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1631–1637 (2010).■■ The first evidence demonstrating the association of Ikkα mutations and human genetic disease.

- 77.Charalambous MP, Lightfoot T, Speirs V, Horgan K, Gooderham NJ: Expression of COX-2, NF-κB-p65, NF-κB-p50 and IKKα in malignant and adjacent normal human colorectal tissue. Br. J. Cancer 101, 106–115 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Merkhofer EC, Cogswell P, Baldwin AS: Her2 activates NF-κB and induces invasion through the canonical pathway involving IKKα. Oncogene 29, 1238–1248 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Page A, Navarro M, Garín M et al. : IKKβ leads to an inflammatory skin disease resembling interface dermatitis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 130(6), 1598–610 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Website

- 101.National Cancer Institute. Cancer Genome Anatomy Project http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Chromosomes/Mitelman