Abstract

Pandemic COVID-19 has put unprecedented pressure on NHS providers to offer non face-to-face consultation. This study aims to assess acceptability of patients and clinicians towards teleconsultation in oral and maxillofacial surgery compared with an expected face-to-face assessment. 340 telephone clinic patient episodes were surveyed over the initial 7-week period of pandemic-related service restriction. Appointment outcomes from a further 420 telephone consultations were additionally scrutinised. A total of 59.1% of patients expressed a strong preference for teleconsultation with only 13.1% stating a moderate or strong preference for face-to-face assessment. Diagnostic accuracy was highlighted as a concern for both clinicians and patients due to inherent inability to conduct a traditional clinical examination, notable in 43.5% of qualitative comments. Logistical concerns, communications needs and other individual circumstances formed the other emerging themes. The majority of remote consultations (59.5%) were outcomed as requiring further review. A total of 29.3% of patients were discharged. These findings suggest that the increasing use of remote follow-up in carefully selected subgroups can facilitate efficient and acceptable healthcare delivery. Although ‘in-person’ clinical appointments will continue to be regarded as the default safe and gold standard management modality, OMFS departments should consider significant upscaling of teleconsultation services.

Keywords: Innovation, telecommunication, satisfaction, risk management

Introduction

The emergence and rapid global spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and its primary illness COVID-19, from Wuhan, China, was declared a pandemic by the Worth Health Organization on March 11, 2020.1 At least 9.8 million confirmed cases and 495,760 global deaths have been recorded to date.2

Emerging stresses on the United Kingdom’s National Health Service resulted in overnight changes to the provision of healthcare services as authorities looked to minimise droplet-related transmission and protect vulnerable populations. Guidance from professional bodies such as the British Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (BAOMS) and British Association of Oral Surgeons (BAOS) mandated limitation of aerosol generating oropharyngeal procedures to urgent cases only. Face-to-face (F2F) contacts were limited and remote consultation for all non-urgent interactions was advised.3 Virtual clinics in oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMFS) have previously shown cost effectiveness and a reduction in non-attendance in certain clinical circumstances.4, 5 COVID-19 has thus given impetus to the strategic shift towards their wider use in anticipation of an unprecedented backlog of referrals and waiting lists for treatment.

Material and methods

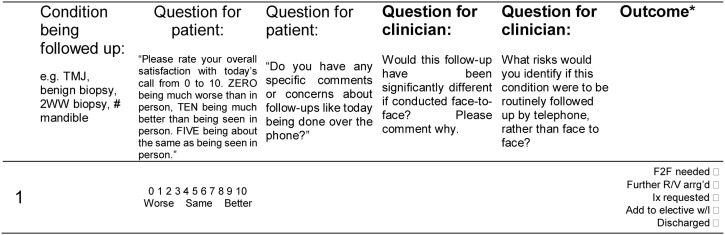

Patients and clinicians were invited, subject to informed consent, to complete an anonymised, prospective survey (Fig. 1 ) at the end of their telephone appointments between 23rd March and 8th May 2020 (7 weeks). Only follow-up consultations and cancer pathway referrals were scheduled during this period. Patients were asked to rate their satisfaction with the telephone follow-up in comparison to a hypothetical F2F encounter on a numerical rating scale (NRS) from zero (F2F greatly preferred) to ten (‘teleconsultation’ greatly preferred). They were invited to offer comments or concerns regarding their teleconsultation experience. Clinicians were asked to note the reason for the appointment, whether anything would have been different if it had been a F2F visit and to comment on any concerns or risks they might attribute to the remote consultation.

Fig. 1.

Sample survey record sheet for clinicians.

*Outcome data column was added to an amended survey during the final 4 weeks of data collection.

Outcome data were recorded during the final four weeks of data collection. A further series of telephone outcomes were recorded retrospectively using electronic medical records (including some who had not been survey participants). These outcomes were recorded in one of four ways: (1) F2F appointment/further review arranged; (2) investigations arranged; (3) added to waiting list for surgery; (4) patient discharged.

Data analysis

Data input and processing was undertaken using Microsoft Excel for Mac Version 16.32.6 Conditions of follow-up were categorised according to a modified version of the General Medical Council’s OMFS syllabus and addition of an ‘other’ category where the diagnostic group is unclear (Table 2 and Fig. 1).7

Table 2.

Patient reported satisfaction with teleconsultation compared with face-to-face alternative; overall and broken down by condition (n = 337).

| Total | Strongly preferred F2F |

Moderately preferred F2F |

Modes are equivalent |

Moderately prefer teleconsultation |

Strongly preferred teleconsultation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | % | no. | % | no. | % | no. | % | no. | % | ||

| Overall | 337 | 16 | 4.7 | 28 | 8.3 | 52 | 15.4 | 42 | 12.5 | 199 | 59.1 |

| By condition: | |||||||||||

| Benign conditions of oral mucosa/soft tissue | 87 | 4 | 4.6 | 4 | 4.6 | 18 | 20.7 | 9 | 10.3 | 52 | 59.8 |

| Impacted teeth or benign jaw pathology | 44 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 6.8 | 6 | 13.6 | 5 | 11.4 | 30 | 68.2 |

| Temporomandibular joint disorders | 45 | 3 | 6.7 | 5 | 11.1 | 6 | 13.3 | 5 | 11.1 | 26 | 57.8 |

| Skin cancer of the head and neck | 45 | 3 | 6.7 | 4 | 8.9 | 7 | 15.6 | 4 | 8.9 | 27 | 60.0 |

| Head and neck cancer (non-cutaneous) | 25 | 2 | 8.0 | 6 | 24.0 | 3 | 12.0 | 4 | 16.0 | 10 | 40.0 |

| Salivary gland disease | 23 | 1 | 4.3 | 1 | 4.3 | 5 | 21.7 | 5 | 21.7 | 11 | 47.8 |

| Cranio-maxillofacial trauma | 16 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 12.5 | 3 | 18.8 | 11 | 68.8 |

| Dental extraction (non-surgical) | 25 | 1 | 4.0 | 2 | 8.0 | 3 | 12.0 | 4 | 16.0 | 15 | 60.0 |

| Other (not specified) | 11 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 9.1 | 1 | 9.1 | 1 | 9.1 | 8 | 72.7 |

| Facial Pain | 6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 16.7 | 1 | 16.7 | 4 | 66.7 |

| Infections of the head and neck | 7 | 1 | 14.3 | 1 | 14.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 14.3 | 4 | 57.1 |

| Orthognathic surgery | 3 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 33.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 33.3 |

Satisfaction ratings were subdivided into 5 categories: ‘strongly prefers F2F consultation’ (score 0-2); moderately prefers F2F consultation (score 3-4), equivalent (score 5), moderately prefers teleconsultation (score 6-7), strongly prefers teleconsultation (score 8-10).

Free text responses from patients and clinicians were interpreted qualitatively. Semantic themes were developed inductively in response to patient and clinician comments. Authors independently familiarised themselves with the data and produced a list of themes and subthemes to classify respondents’ comments. The list was subsequently refined to remove tautological ideas and ensure coherence.8 Only subthemes occurring with a frequency of one percent or greater were considered for inclusion in the study narrative.

Results

Outcome comparison

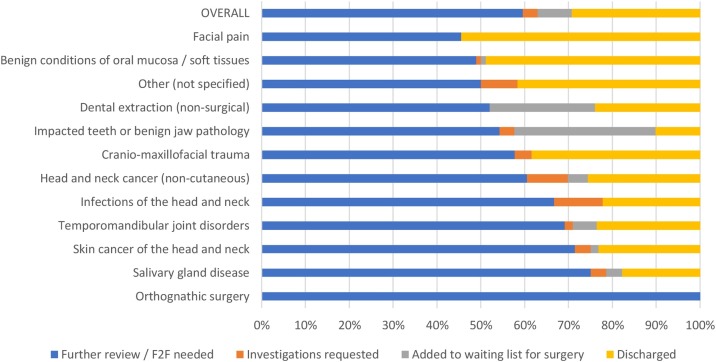

200 prospective and 220 retrospective appointment outcomes were recorded: 250 (59.5%) of the total required on-going review, 14 (3.3%) further diagnostic investigation, 33 (7.9%) added to a surgical waiting list, and 123 (29.3%) discharged. Table 1 and Fig. 2 illustrate outcomes according to diagnostic group.

Table 1.

Outcomes (n = 420) of remote clinics overall and by diagnostic group.

| Facial pain | Benign conditions of the oral mucosa/soft tissues | Other (not specified) | Dental extraction (non-surgical) | Impacted teeth or benign jaw pathology | Craniomaxillofacial trauma | Head and neck cancer (non-cutaneous) | Infections of the head and neck | Temporomandibular joint disorders | Skin cancer of the head and neck | Salivary gland disease | Orthognathic surgery | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Further review/F2F needed | 5 | 46 | 6 | 13 | 32 | 15 | 26 | 6 | 38 | 40 | 21 | 2 | 250 (59.5%) |

| Investigations requested | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 14 (3.3%) |

| Added to waiting list for surgery | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 19 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 33 (7.9%) |

| Discharged | 6 | 46 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 2 | 13 | 13 | 5 | 0 | 123 (29.3%) |

| Total (% of n = 420) | 11 (2.6%) | 94 (22.4%) | 12 (2.9%) | 25 (6.0%) | 59 (14.0%) | 26 (6.2%) | 43 (10.2%) | 9 (2.1%) | 55 (13.1%) | 56 (13.3%) | 28 (6.7%) | 2 (0.5%) | 420 |

Fig. 2.

Proportional outcomes (n = 420) of remote clinics overall and by diagnostic group.

Patient satisfaction

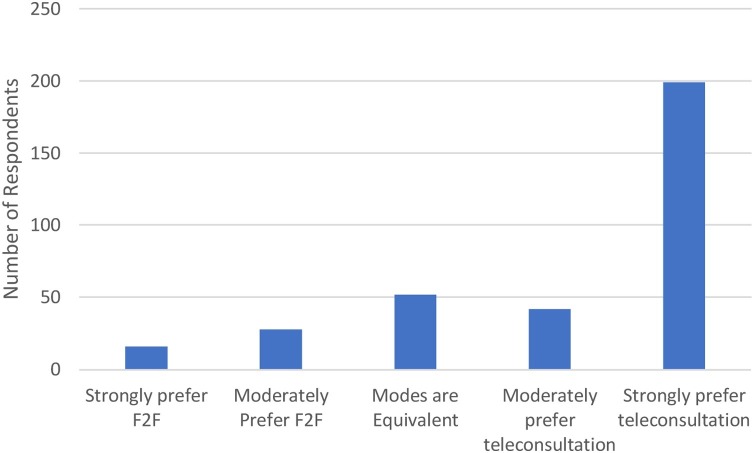

Surveys were completed by 340 patients of whom 337 offered a rating of their satisfaction in comparison to a hypothetical F2F encounter. 59.1% of respondents reported a strong preference for teleconsultation (Table 2 and Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Overall patient satisfaction (n = 337) with teleconsultation compared with F2F consultation.

‘Tele’ follow-up versus face-to-face – a thematic comparison

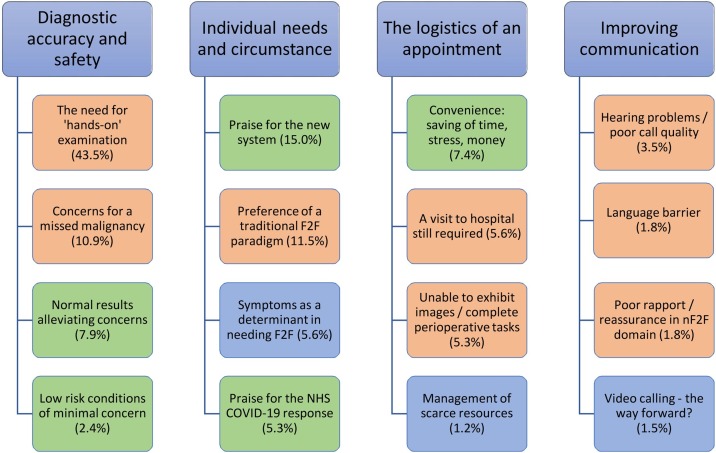

Just over half (n = 177, 52.1%) of 340 surveyed appointments yielded patient comments and 228 (67.1%) prompted clinician responses. Individuals sometimes made multiple comments and individual response occasionally spanned various themes. In total, 456 separate points were considered (191 from patient comments and 265 from clinicians). Four main themes emerged: (1) diagnostic accuracy and safety; (2) individual needs and circumstances; (3) appointment logistics; and (4) improving communication (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Patient and OMFS clinicians experiences of teleconsultation: themes and subthemes; percentages indicate the frequency of themes emerging from our cohort of consultations (n = 340). Subthemes colour coded as follows: green indicating positive towards non-F2F modality, red negative against non-F2F, blue neutral observation.

Diagnostic safety and accuracy

Patients and clinicians viewed ‘hands-on’ clinical evaluation as being a cornerstone of diagnostic accuracy, citing the additional reassurance and improved recognition of urgent or hidden pathology they thought this would provide. This was the most common theme. Nonetheless, respondents commented that the availability of special investigation results (histology, radiology, haematology/biochemistry) carried great reassurance. Benign and low-risk conditions were identified as being acceptable for the non-F2F arena.

Individual needs and circumstance

Patient comments frequently praised the NHS and its keyworkers in their efforts to manage the difficult circumstances generated by the COVID-19 pandemic. One subgroup mentioned a preference of F2F consultation generally, whilst another highlighted that the severity of symptoms would dictate their preference between a teleconsultation or a F2F encounter.

The logistics of an appointment

Patients responded positively to the time, effort and cost-related economies they generated via the non-F2F format. A subgroup of patients and clinicians reported that attendance to hospital would facilitate certain logistical tasks, such as the use of radiographs as visual aids, or completing diagnostic procedures such as ultrasonography or blood tests. In many circumstances, the need for physical attendance cannot be entirely removed.

Improving communication

Hearing difficulties, language barriers and technical issues were reported as potential or actual concerns, leading to deleterious effects on rapport-building (at a minimum) or (at an extreme) a total failure to achieve the goal of the consultation.

Discussion

This paper aims to identify patient groups within OMFS who would benefit from remote follow-up beyond the current COVID-19 crisis and describes attitudes towards and perceived risks of remote consultation.

The outcome survey demonstrates differences in the effects of teleconsultation dependant on the OMFS diagnostic group being investigated. Higher rates of ‘progress’ (addition to waiting list, decision for specialty investigation, discharge from department) were associated with more benign soft and hard tissue oral health conditions, trauma and facial pain (Fig. 2). More complex head and neck conditions including salivary gland diseases, temporomandibular joint disorders, orthognathic surgery, and head and neck cancer patients demonstrated a higher proportion (>60%) requiring ongoing active monitoring or F2F assessment. It would be worth distinguishing between patients who are undergoing active monitoring long-term and those who are in the early diagnosis/management phase of their care, as it is likely that the usefulness of remote follow-up would differ significantly in these groups (but lies beyond the scope of data captured in the current study). In terms of case selection, every department should develop a follow-up protocol which aims for maximal efficiency without compromising on patient safety. Unfortunately, direct comparison of F2F clinics from a 2019 pre-pandemic period with the current study cohort to investigate the efficiency of remote methods of contact was not possible owing to significant differences between these groups resultant from the suspension of new non-emergency healthcare visits (including all non-cancer OMFS referrals).

Satisfaction with nF2F follow-up was high amongst all individual diagnostic groups except orthognathics (Fig. 3 and Table 2), for which participant numbers were few. Overall, patient groups were willing to embrace these largely unfamiliar methods of healthcare contact, particularly if there was progression of the patient journey. It is difficult to know if this positivity would have been so prevalent without the COVID-19 backdrop and whether this is a sentiment that will last.

Thematic analysis from the outset demonstrated that diagnostic accuracy and patient safety are crucial in considering initiatives such as remote reviews. This was identified as a potential shortcoming of a consultation unaccompanied by physical examination. It may be possible to mitigate these concerns with video calling and clinical photography. In potentially serious pathology such as head and neck malignancy or complex conditions such as facial disproportion and salivary gland disease, a ‘hands-on’ approach to follow-up will likely continue to be regarded as the gold standard of care.

Limitations

This survey revealed a sentiment among patients that may be described as ‘patriotic’. A subgroup of patients rated their teleconsultations very highly whilst objectively commenting that their remote follow-up was only acceptable given the current public health crisis. COVID-19-related goodwill towards clinicians, or potentially a fear of exposure to the pathogen itself, may have temporarily skewed responses in favour of teleconsultation. The survey could be regarded as having captured the zeitgeist of a pivotal moment in the history of our health service. Having made subtle changes in data capture - recording anonymised outcomes prospectively following an initial pilot survey and inclusion of some retrospective outcomes, some quantitative data was included in the analyses. Diagnosis coding occurred post hoc rather than prospectively, which resulted in a small number of encounters requiring categorisation as ‘other’ and thus lost to further scrutiny.

There was a limited scope for direct comparison with non-pandemic times during the survey period, owing to the stoppage of new non-cancer appointments and a hold on elective surgery progress. Nationally organised sub-specialty management pathways and variation with local case-load referral patterns means that no cleft, dental implant restorative or aesthetic procedures are included within the Royal Free London’s OMFS department thus limiting the cross-applicability of results to other institutions that do offer these services.

Implications for practice

A willingness by patients and clinicians to experiment with virtual consultation in OMFS has been suggested by other authors.9 Patients consulted via telephone during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated high satisfaction and took a pragmatic approach in recognising the inherent limitations. Clinicians conducting teleconsultations identified concerns over diagnostic uncertainty, particularly in presentations where serious pathology needed exclusion. We suggest that clinician and patient confidence with remote methods is likely to increase in proportion with their increased familiarity brought about by the rapid, enforced and dramatic changes in healthcare services mandated by the COVID-19 pandemic, with some of these changes likely to persist in the long-term.

High-risk OMFS conditions and head and neck cancer patients will continue to need in-person specialty review as the gold standard of care. Potentially vulnerable patient groups such as children or those with communication difficulties or language barriers will continue to need a F2F assessment due to the uncertain potential for miscommunication with remote methods of contact. In cases where postsurgical evaluation is required (e.g. craniomaxillofacial trauma, open salivary surgery), the authors recommend that, following a postoperative F2F assessment, remote follow-up should be instituted as standard, with F2F follow-up to be used only where clinically justifiable. In low-risk, benign and symptomatically quiescent presentations, the logistical benefits to a remote follow-up are readily recognisable. In a post-pandemic national health service, with institutional inertia having been unceremoniously dismantled, the authors envision a shift in favour of these convenient and innovative methods of communication.

Conclusions

The authors determine that there are clear indications that non-F2F follow-up is both an acceptable modality to patients and, with judicious case selection, safe from a clinicians’ standpoint. The current pandemic has driven far-reaching changes in all sectors: healthcare generally, and surgical specialties (OMFS in particular) have been pushed to adapt without warning. Available technologies should be utilised to their fullest extent to improve the patient experience both presently and beyond the current global health crisis.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement/confirmation of participants’ permission

This survey was conducted within the Trust’s formal clinical governance framework with ethical approval not necessary. Contributing clinicians and patients agreed to the use of anonymised data for the purposes of service improvement and any publications that may derive thereof.

Acknowledgements

We thank the OMFS teams at Barnet and Chase Farm Hospitals, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust and Dr Anna Remington for their contributions to this work.

References

- 1.Ghebreyesus TA, Coronavirus disease 2019 - Events as they happen, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen. [Accessed 27 Jun 2020].

- 2.WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. [Accessed 28 Jun 2020].

- 3.Magennis P, Coulthard P. BAOS & BAOMS – Guidance for the care of OMFS and Oral Surgery patients where COVID is prevalent. 12 May 2020. https://www.baoms.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/professionals/covid_19/baos_baoms_covid19_postions_paper_final.pdf.

- 4.Diamanti C.M., Shah M. The cost and clinical effectiveness of a telephone biopsy results clinic. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;56:e58–e59. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wells J.P., Roked Z., Moore S.C. Telephone review after minor oral surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;54:526–530. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Microsoft . Microsoft Corp.; 2019. Microsoft Excel for Mac, Version 16.32. [Google Scholar]

- 7.GMC. Oral and maxillofacial surgery curriculum 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/OMFS_inc._Trauma_TIG.pdf_72601045.pdf. [Accessed 20 Jun 2020].

- 8.Patton M. 4th ed. Sage Publishing; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2014. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Izzi T., Breeze J., Elledge R. Clinicians’ and patients’ acceptance of the virtual clinic concept in maxillofacial surgery: a departmental survey. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;58:458–461. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]