In response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, gastrointestinal professional societies initially provided guidance to delay all elective endoscopies and to perform only urgent or emergent procedures.1 This resulted in endoscopy centers operating at less than 25% of normal volume.2 In early April, plans to reopen endoscopy units had begun. Because almost half of coronavirus infections are transmitted by asymptomatic or presymptomatic individuals, gastrointestinal societies advised obtaining a negative severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) molecular test for all patients within 48–72 hours before endoscopy to prevent viral transmission.3 , 4

Despite SARS-CoV-2 molecular testing recommendations for endoscopy centers, there is little evidence to support their effectiveness. Stanford University Medical Center reported 1 in 694 ambulatory SARS-CoV-2–positive tests, which is a positive percentage of 0.14% compared with 4.34% in Santa Clara County from April 1 to May 31.5 In this study, we report on outcomes of universal 48- to 72-hour preprocedure SARS-CoV-2 testing over a 2-month period from May 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020 after reopening an adult and pediatric endoscopy center in New York City, the global epicenter of the pandemic, and to compare those results with the New York City and New York State SARS-CoV-2–positive percentages during that time.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of all patients undergoing endoscopy and subsequent preprocedure SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing at the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City from May 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020. Almost all testing was performed at the Mount Sinai Hospital. Procedures were postponed at least 14 days for a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test, unless classified as emergent. Universal COVID-19 infection prevention precautions were observed for all patients, regardless of testing outcome, in accordance with joint gastrointestinal societal guidance. State and local PCR testing data were obtained from the New York State Department of Health. A Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare the percentage of positive PCR tests between the Mount Sinai Hospital, New York State, and New York City, with an alpha equal to 0.05.

Results

During the study period, 623 SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests in 589 asymptomatic adults (52% men; median age, 62 years [interquartile range, 47–78]) and 34 children younger than age 18 years were administered 48–72 hours before all endoscopic procedures at The Mount Sinai Hospital. Six tests had a positive result. Of these 6 cases, 5 were postponed and 1 upper endoscopy was performed for suspected esophageal varices (Table 1 ). The total percentage of positive tests in endoscopy patients from May 1 to June 30 was 0.96% (6/623). There were 2 of 158 positive tests (1.27%) in May and 4 of 465 (0.86%) in June. There were no positive tests in 34 children tested.

Table 1.

Outcomes of Patients with SARS-CoV-2–positive PCR Tests Before Endoscopy

| Patient Identification | Age (y) | Gender | Indication | Procedure(s) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 63 | Male | Colorectal cancer screening | Colonoscopy | Postponed and not yet performed |

| 2 | 78 | Male | Choledocholithiasis | Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography | Postponed and performed 17 days after positive PCR test |

| 3 | 60 | Female | Abdominal pain and jaundice | Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography | Postponed and not yet performed |

| 4 | 65 | Male | Abdominal pain | Upper endoscopy | Postponed and not yet performed |

| 5 | 75 | Male | Colon polyps | Colonoscopy with polypectomy | Postponed and performed 22 days after positive PCR test |

| 6 | 28 | Male | Portal hypertension | Upper endoscopy with variceal banding | Performed 2 days after positive PCR test, 7 days after positive COVID-19 antibody test |

Comparison With New York State and New York City

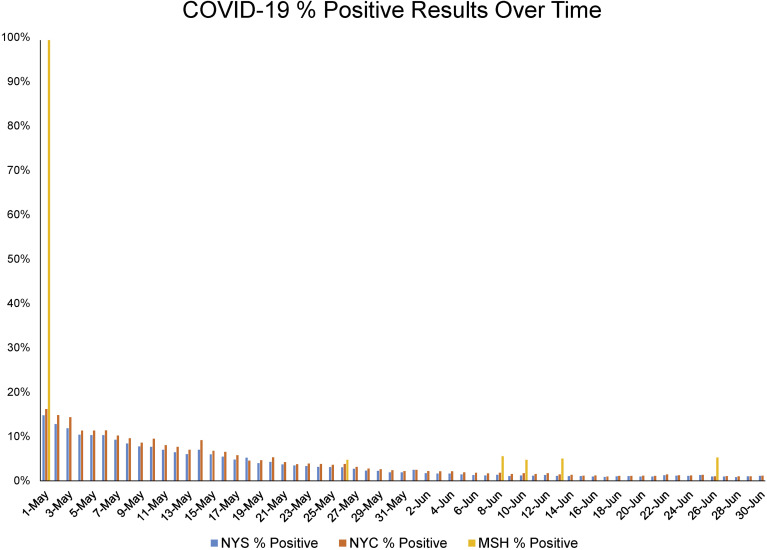

In May, 1.27% of endoscopy patients (2/158) tested positive. This was significantly lower than that reported by New York State (5.34%; 63,397/1,186,330) and New York City (6.27%; 34,074/543,214; P < .0001). Similarly, in June, the positive percentage in endoscopy patients (0.86%; 4/465) was lower than that in New York State (1.20%; 22,368/1,857,871) and New York City (1.43%; 11,711/816,215; P < .0001). Overall, the percentage of SARS-CoV-2–positive tests was lower in asymptomatic endoscopy patients (0.96%; 6/623) than in the population tested in New York State (2.82%; 85,765/3,044,201) and New York City (3.37%; 45,785/1,359,429) during the study period (P < .0001) (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Percentage of positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests from May 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020. Percentage of positive SARS-CoV-2 tests in asymptomatic routine ambulatory endoscopy patients (MSH % Positive) is shown in comparison with the percentage of positive tests in New York State (NYS % Positive) and New York City (NYC % Positive) from May 1, 2020 until June 30, 2020.

Discussion

This is the first study of outcomes for universal SARS-CoV-2 testing in an ambulatory endoscopy center from New York City, the area with the highest prevalence of COVID-19 in the United States. These data suggest that a SARS-CoV-2–positive PCR test in an asymptomatic ambulatory endoscopy patient is a rare event, with an overall percentage positive of <1%. As the SARS-CoV-2 percentage positive decreased in the local and state population from May to June, the percentage positive also decreased slightly in those undergoing endoscopy from 1.27% in May to 0.86% in June, despite almost triple the amount of patients tested in June compared with May. These findings are consistent with those from Stanford University Medical Center and Santa Clara County, a lower prevalence area than New York City, that SARS-CoV-2 positivity in asymptomatic ambulatory endoscopy patients is a rare event.5

In our study, no children tested PCR positive before endoscopy. More studies are needed to determine if routine screening of asymptomatic children before endoscopy is necessary in areas of low prevalence to prevent viral transmission.

Endoscopy is an aerosolizing procedure. SARS-CoV-2 can be detected in the air 3 hours after aerosolization.6 , 7 The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected in feces of COVID-19 patients, yet live virus was never isolated from stool samples, even in samples with a high viral RNA concentration, suggesting fecal-oral transmission may be a less likely method of viral transmission.8 Based on our findings that SARS-CoV-2–positive tests in asymptomatic ambulatory patients undergoing routine endoscopy are rare, universal COVID-19 infection precautions alone for all cases, in the absence of available testing, may be sufficient to prevent viral transmission in endoscopy centers. The combination of preprocedure testing and universal infection control precautions would make the spread of COVID-19 in an endoscopy center unlikely and endoscopy a safe procedure in any area of prevalence during the pandemic. Use of this preprocedure testing and infection control strategy could potentially allow endoscopy centers to remain open, even during periods of increased local SARS-CoV-2 infection rates, which could ultimately result in improved screening practices and fewer cases of missed colon cancer, for example.

In conclusion, SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity is rare in a population of asymptomatic patients undergoing routine ambulatory endoscopy. The combination of preprocedure PCR testing and infection control strategies are likely to be sufficient in preventing viral transmission in endoscopy centers, even in areas of higher prevalence. Frontline providers should pay close attention to local infection rates when planning endoscopic procedures for patients. Further, multicenter studies are needed as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to assess the safety of preprocedure endoscopic protocols to prevent viral transmission.

Acknowledgments

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Michael Todd Dolinger, MD, MBA (Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead; Investigation: Lead; Methodology: Equal; Writing – original draft: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Nikhil A. Kumta, MD, MS (Conceptualization: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Equal; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Equal). David A. Greenwald, MD (Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Marla C. Dubinsky, MD (Conceptualization: Lead; Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Supervision: Lead; Writing – original draft: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Lead).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest These authors disclose the following: Marla C. Dubinsky is a consultant for Abbvie, Allergan, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, BoehringerIngelheim, Celgene, Ferring, Genentech, Gilead, Hoffmann-La Roche, Janssen, Pfizer, Prometheus Biosciences, Takeda, and Target PharmaSolutions and receives research funding from Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer, Prometheus Biosciences, and Takeda. Nikhil Kumta is a consultant for Apollo Endosurgery, Boston Scientific, Gyrus ACMI Inc, GLG consulting, and Olympus.

Funding No specific funding from any agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors has been provided for this research.

References

- 1.https://webfiles.gi.org/links/media/Joint_GI_Society_Guidance_on_Endoscopic_Procedure_During_COVID19_FINAL_impending_3312020.pdf Available at:

- 2.Forbes N. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:772–774.e13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavezzo E. Nature. 2020;584:425–429. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2488-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.https://webfiles.gi.org/docs/policy/2020resuming-endoscopy-fin-05122020.pdf Available at:

- 5.Podboy A. Gastroenterolog. 2020;159:1586–1588. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinonquel P. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:723–731. doi: 10.1111/den.13706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguila E. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;4:324–331. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfel R. Nature. 2020;581:465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]