ABSTRACT

Objective:

We developed a rehabilitation robot to assist hemiplegics with gait exercises. The robot was combined with functional electrical stimulation (FES) of the affected side and was controlled by a real-time-feedback system that attempted to replicate the lower extremity movements of the non-affected limb on the affected side. We measured the reproducibility of the non-affected limb movements on the affected side using FES in non-disabled individuals and evaluated the smoothness of the resulting motion.

Method:

Ten healthy men participated in this study. The left side was defined as the non-affected side. The measured hip and knee joint angles of the non-affected side were reproduced on the pseudo-paralytic side using the robot’s motors. The right quadriceps was stimulated with FES. Joint angles were measured with a motion capture system. We assessed the reproducibility of the amplitude from the maximum angle of flexion to extension during the walking cycle. The smoothness of the motion was evaluated using the angular jerk cost (AJC).

Results:

The amplitude reproduction (%) was 87.9 ± 6.2 (mean ± standard deviation) and 71.5 ± 10.7 for the hip and knee joints, respectively. The walking cycle reproduction rate was 99.9 ± 0.1 and 99.8 ± 0.2 for the hip and knee joints, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences between results with FES versus those without FES. The AJC of the robot side was significantly smaller than that of the non-affected side.

Conclusions:

A master–slave gait rehabilitation system has not previously been attempted in hemiplegic patients. Our rehabilitation robot showed high reproducibility of motion on the affected side.

Keywords: feedback system, functional electrical stimulation, hemiplegia, robotic therapy

INTRODUCTION

A basic premise of motor learning rests on the notion of high-volume repetition and task-oriented training. Treatments based on this premise have become a major area of focus for research in post-stroke motor function recovery.1,2,3) For such high-frequency training, robot rehabilitation is considered useful. Because robots can be programmed to assist in a variety of goal-oriented movements, they can enrich conventional physiotherapy and optimize post-stroke gait rehabilitation.

Most existing robotic devices are designed to reproduce a predetermined trajectory or are used as auxiliary support only for gait. Consequently, the use of such robots means that the patient has to learn a new method of walking that is different from normal walking. To acquire a new gait entails not only regaining lost motor function, but also learning sensory function. Therefore, it potentially takes time to reacquire gait function. We developed a feedback system based on data from the motion of the non-disabled lower extremity. Data were acquired from nine-axis sensors (using accelerometers, gyroscopes, and geomagnetometers). Using the data from the non-disabled limb, the robot reproduces the motion in the disabled lower limb. We hope to improve the efficiency of learning exercises by employing an errorless learning approach that reproduces as closely as possible the movement of a normal gait in the affected limb.

Waste atrophy occurs in the muscle of paralyzed limbs when automatic exercise capacity is low. Therefore, it is necessary to reacquire atrophied muscular strength while waiting for the paralysis to improve. However, it is difficult to reacquire muscle strength in a paralyzed limb. Nonetheless, improved muscle strength is important to promote the improvement of paralysis. By using functional electrical stimulation (FES), walking training supported by automatic muscle contraction is possible early after the occurrence of disability. Muscle contraction invoked by FES can cause muscle fatigue, but Shimada et al. reported that a hybrid FES and orthosis reduced the need for electrical stimulation, thereby minimizing muscle fatigue.4) The assist function of the robot makes it possible to continue walking training even if muscle fatigue occurs.

To the best of our knowledge, no study to date has examined the use of FES and feedback systems based on the motion of the non-disabled lower extremity. We developed a rehabilitation robot to assist hemiplegics with gait exercises. The system includes FES of the affected side and real-time feedback of the movements of the non-affected limb to the affected side. However, the level of reproducibility of the feedback system is unclear. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the reproducibility of the non-affected lower limb movements on the affected side using FES in non-disabled individuals. We compared the reproducibility with FES versus that without FES and evaluated the smoothness of the resulting motion.

METHODS

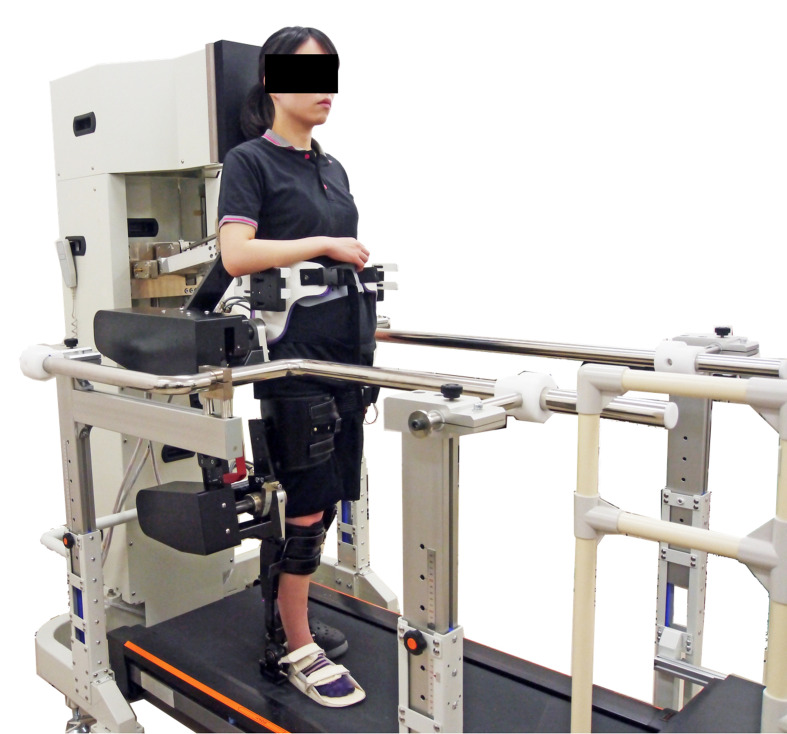

Ten healthy men (aged 22–24 years) participated in this preliminary experimental investigation. The robot design was based on hip–knee–ankle orthosis, and the left side was defined as the non-affected side (Fig. 1). By reproducing the movement of the non-affected half-gait cycle in the next affected-side half-gait cycle, we obtained feedback and reproduced one full gait cycle in real-time. Both hip and knee joints were flexible in the direction of flexion–extension: hip joints were flexible from 45° of flexion to 45° of extension, and knee joints were movable from 75° of flexion to 20° of extension. The motor-assist torque could be changed from 0–100% as necessary for walking. Nine-axis sensors (IMU-Z2, ZMP Inc., Tokyo, Japan) were attached to the thigh and lower leg of the non-affected side. The measured hip joint and knee joint angles of the non-affected side were reproduced on the right, pseudo-paralytic side using the robot’s motors in real time. The quadriceps femoris muscle of the right side was stimulated with FES (Dynamid, DM2500, Minato Medical Science Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) from terminal-swing to mid-stance. Stimulation was performed on the motor points, as confirmed by palpation of the superior iliac spines and femoral lateral condyles5)(Fig. 2). The stimulus setting was 25 Hz and 20–25 mA; it was set at the minimum stimulus that caused knee extension movement as the rest motor threshold.

Fig. 1.

Gait rehabilitation robot. The robot includes a functional electrical stimulation system for the affected side and a real-time-feedback system that attempts to reproduce the lower extremity movements of the non-affected limb on the affected side.

Fig. 2.

Nine-axis sensors were attached to the thigh and lower leg of the non-affected side. The quadriceps femoris muscle was stimulated using functional electrical stimulation. The stimulation points were based on the motor points.

The participants walked with the robot’s full assistance for 3 min with FES and 3 min without FES at a rate of 0.8 km/h; joint angles were measured using the OptiTrack motion capture system (Trio V120, NaturalPoint, Inc., Oregon, USA). The sampling rate of the axis sensors and the motion capture system was 50 Hz. We assessed the rate of reproducibility of the amplitude from the maximum angle of flexion to extension and throughout the walking cycle of each participant. We compared the mean reproducibility both with FES and without FES. To evaluate the smoothness of each joint motion, angular jerk was determined by differentiating the angle of each joint three times with respect to time in the three groups: control (normal gait), with FES, and without FES. In addition, referring to the report of Flash et al.,6) the sum of the angular jerks (i.e., the angular jerk cost, AJC) was calculated. Smaller AJC values indicate that the movement of each joint is smooth.

This study was approved by our institution’s ethics committee. All individuals participated voluntarily and provided written informed consent.

Statistical Analysis

The reproduction rates of the amplitude and walking cycle with and without FES were compared using the paired t-test. AJC was compared using one-way ANOVA. All statistical analyses were conducted using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan).7) P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The reproduction rate (%) of amplitude and the walking cycle are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between values with FES and without FES.

Table 1. Reproducibility of the knee and hip angles and the whole cycle.

| FES (+) | FES (−) | P | ||

| Angle | Hip joint | 87.9 ± 5.9 | 87.4 ± 8.0 | 0.76 |

| Knee joint | 72.3 ± 11.8 | 70.1 ± 12.4 | 0.68 | |

| Cycle | Hip joint | 98.6 ± 3.8 | 99.7 ± 0.2 | 0.13 |

| Knee joint | 99.9 ± 0.1 | 99.8 ± 0.2 | 0.13 |

Data are percentages expressed as means±standard deviations.

FES, functional electrical stimulation.

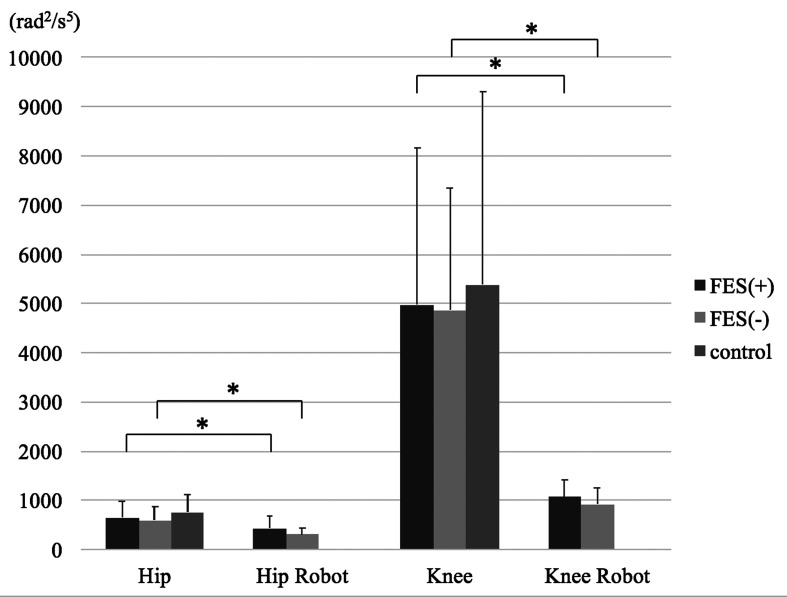

Figure 3 shows the results of AJC. In both joints, the AJC of the robot side was significantly smaller than the non-affected side. There were no significant differences between the three groups in both non-affected side’s joints.

Fig. 3.

The angular jerk cost (AJC) of the hip and knee joint with and without functional electrical stimulation.

*Significance set at P<0.05.

In the both joints, AJC of the robot side was significantly smaller than the non-affected side. There were no significant differences between the three groups in both non-affected side’s joints and the FES and without FES groups.

DISCUSSION

We developed a rehabilitation robot to assist hemiplegics with gait exercises. The system includes FES of the affected side and a real-time-feedback system that gathers data from the lower extremity movements of the non-affected limb for application to the affected side.

In patients with central nervous system disorders, the peripheral nerves and their dominant muscles maintain electrical excitability, and control by FES can support walking.8) In conventional rehabilitation robots, because the driving force is a motor or similar device worn outside the body, assistance is possible, but it is difficult to stimulate the paralyzed muscle directly to activate it. By using FES together with a robot, it is possible to directly stimulate the lower limb muscle during walking exercise. This approach is hoped to combine the assistance effect from the robot and a training effect on the paralyzed muscle.9)

FES produces activity in the bilateral somatosensory cortices (SMC), which is seen to continue over time.10) Furthermore, activation is bilateral and extensive before stimulation, but localized to the SMC after intervention.10) By simultaneously performing FES and voluntary movement, decreases in blood flow in the non-affected-side sensorimotor cortex and increases in blood flow in the affected-side sensorimotor cortex have been documented.11)

When multiple devices operate in cooperation, the control side is termed the master and the controlled side is termed the slave. A master–slave system is used in robotic surgery12) and in an upper limb rehabilitation robot.13) Such a master–slave robot can achieve an adequate trajectory for an individual patient without any previous data or calculation. For hemiplegics, a master–slave robotic rehabilitation system for the lower limb that uses a feedback system from the non-affected limb has not before been attempted. However, it is encouraging that the reproducibility of the movement of the lower limb could be confirmed using such a system in the current study.

Previous rehabilitation techniques have tended to emphasize reinforcement of residual functions and the use of compensatory functions, rather than aiming for recovery through active intervention designed to address the functional impairment. However, in recent years, experimental proof that plasticity exists in humans has been presented,14) and there have been impressive developments in regenerative medicine. With the goal of attaining functional recovery by taking plasticity into account, we are entering a new era of building effective strategies to develop improved rehabilitation techniques. Currently, three factors affecting the development of rehabilitation need to be addressed: dose dependency, task specificity, and neural plasticity.15,16) These techniques represent neuro-rehabilitation, the basic strategy of new rehabilitation methods trying to match the exercise image with sensory feedback.

Tactile experience based on somatosensory feedback is important for restoring motor function after stroke.17) Based on our results, our rehabilitation robot showed high reproducibility and accuracy compared with the results of Ota et al.18) In the future, we will proceed with reliability testing with hemiplegic patients and aim for practical applications of this new gait rehabilitation robot for the treatment of hemiplegia.

Our results demonstrated the noninferiority of reproducibility of lower limb movement using the robot system with FES versus the robot system without FES. The combined use of the robot system and FES did not adversely affect the smoothness of joint motion. In fact, application of the robot and FES maintained the smoothness of walking. Consequently, it may be possible to reproduce normal walking conditions, which may help to improve rehabilitation effects.

This study has some limitations. First, the study participants were healthy volunteers, and were thus different from paralyzed persons. Nevertheless, there were no differences in the support mechanism provided by the robot. Secondly, the FES intensity was low. In future studies, to further optimize the stimulus intensity, we will verify the effects of FES intensity on rehabilitation outcomes. Third, we confirmed the accuracy of lower limb movement reproducibility at a relatively low speed. Furthermore, we measured the AJC to determine whether the movement was disturbed by the robot system. However, AJC levels did not show the effectiveness of the master–slave system and the rehabilitation effect. In future investigations, we will examine the accuracy of the movement and the rehabilitation effect at different walking speeds and torque levels to optimize improvements in paralysis. Fourth, because of limitations in the robot’s joint movements, the maximum movable range could not be replicated, and thus reproducibility was reduced. However, in hemiplegic patients, the maximum movable range of articulation may be less than that in healthy subjects. We will consider expanding the range of motion of the robot’s joints in future research.

In conclusion, we developed a rehabilitation robot that includes FES of the affected side and a real-time-feedback system that attempts to reproduce the lower extremity movements of the non-affected limb on the affected side. The reproducibility of the non-affected lower limb movements on the affected side was high.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Sumito Musaka, Atsuko Harata, Taisei Honda, Kohei Takeda, Takehito Takei, Iori Usuda, Ryo Saito, and Tetsuya Yamauchi for their assistance in data acquisition and development of the robot system. This study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant number 16K01535.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Veerbeek JM,van Wegen E,van Peppen R,van der Wees PJ,Hendriks E,Rietberg M,Kwakkel G: What is the evidence for physical therapy poststroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e87987. , [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lohse KR,Lang CE,Boyd LA: Is more better? Using metadata to explore dose-response relationships in stroke rehabilitation. Stroke 2014;45:2053–2058. , [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeuchi N,Izumi SI: Rehabilitation with poststroke motor recovery: a review with a focus on neural plasticity. Stroke Res Treat 2013;2013:128641. , [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimada Y,Sato K,Abe E,Kagaya H,Ebata K,Oba M,Sato M: Clinical experience of functional electrical stimulation in complete paraplegia. Spinal Cord 1996;34:615–619. , [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato M, Shimada Y, Toshiki M, Chida S, Hatakeyama K: Functional electrical stimulation for paralyzed extremities [in Japanese]. Annual report of the Miyagi Physical Therapy Association 2003;14:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flash T,Hogan N: The coordination of arm movements: an experimentally confirmed mathematical model. J Neurosci 1985;5:1688–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanda Y: Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013;48:452–458. , [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liberson WT,Holmquest HJ,Scot D,Dow M: Functional electrotherapy: stimulation of the peroneal nerve synchronized with the swing phase of the gait of hemiplegic patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1961;42:101–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehrholz J,Elsner B,Werner C,Kugler J,Pohl M: Electromechanical-assisted training for walking after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;CD006185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasaki K,Matsunaga T,Tomite T,Yoshikawa T,Shimada Y: Effect of electrical stimulation therapy on upper extremity functional recovery and cerebral cortical changes in patients with chronic hemiplegia. Biomed Res 2012;33:89–96. , [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hara Y,Obayashi S,Tujiuchi K,Muraoka Y: The effects of electromyography-controlled functional electrical stimulation therapy on hemiparetic upper extremity function and cortical perfusion in chronic stroke patients. Clin Neurophysiol 2013;124:2008–2015. , [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen MM,Das S: The evolution of robotic urologic surgery. Urol Clin North Am 2004;31:653–658, vii. , [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrnstadt G,Alavi N,Randhawa BK,Boyd LA,Menon C: Bimanual elbow robotic orthoses: preliminary investigations on an impairment force-feedback rehabilitation method. Front Hum Neurosci 2015;9:169. , [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liepert J,Miltner WH,Bauder H,Sommer M,Dettmers C,Taub E,Weiller C: Motor cortex plasticity during constraint-induced movement therapy in stroke patients. Neurosci Lett 1998;250:5–8. , [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt RA,Lee TD: Motor Leaning and Performance: From Principles to Application. 5th ed, Human Kinetics, Champaign, 2013;256–284. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nudo RJ,Wise BM,SiFuentes F,Milliken GW: Neural substrates for the effects of rehabilitative training on motor recovery after ischemic infarct. Science 1996;272:1791–1794. , [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaechter JD,van Oers CA,Groisser BN,Salles SS,Vangel MG,Moore CI,Dijkhuizen RM: Increase in sensorimotor cortex response to somatosensory stimulation over subacute poststroke period correlates with motor recovery in hemiparetic patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2012;26:325–334. , [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ota R,Miyoshi T,Komeda T: Development of powered gait orthosis for stroke patients using fluctuating individual gait information [in Japanese]. Proceedings of the Bioengineering Conference, Annual Meeting of BED/JSME 2011;10–74:199–200.