Abstract

Background:

The problem of intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs) in children is one of the most worrisome problems worldwide. The latest estimates indicate that more than 880 million children are in the need of treatment for these parasites.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to measure the prevalence of IPIs in school-going children in East Sikkim, India, and to assess the efficacy of single-dose albendazole (ALB) in children infected with soil-transmitted helminths (STHs).

Subjects and Methods:

A total of 300 stool samples were collected from the schoolchildren of government schools of East Sikkim. Samples were processed for the identification of IPIs by direct microscopy and formalin-ether concentration method. Fecal egg counting was carried out for STH by Stoll's egg counting technique, pre- and posttreatment with single-dose ALB. The second stool samples were collected 10–14 days posttreatment of ALB. Cure rate (CR) and the fecal egg reduction rate (ERR), the two most widely used indicators for assessing the efficacy of an anthelmintic, were used in this study. The data were analyzed and the results were interpreted statistically.

Results:

The overall prevalence of the IPIs was 33.9%. Helminthic infection was 4.6% and protozoan infection was 29.3%. Among helminthes Ascaris lumbricoides and among protozoans Entamoeba spp. were the dominant intestinal parasites. For drug efficacy, A. lumbricoides had CR 55.5% and ERR 81.4%. Moreover, for Trichuris trichiura, CR and ERR was 100%. The study has shown less efficacy against A. lumbricoides infections compared to T. trichiura.

Conclusion:

The study provides useful insight into the current prevalence of IPIs in school-going children in government schools in East Sikkim region. Keeping in view of less efficacy of ALB, it is necessary to keep the monitoring of development of drug resistance simultaneously.

Keywords: Albendazole efficacy, intestinal parasitic infection, school-going children, soil-transmitted helminth

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal parasitic infection (IPI) is endemic worldwide, and it represents a large and serious medical health problem in the developing countries with a high prevalence rate in many regions. It is estimated that 3.5 billion people are affected, and 450 million are ill as a result of these infections, with the majority being children. These infections cause morbidity and mortality along with other manifestations such as iron-deficiency anemia, growth retardation in children, and other physical and health problems.[1] Helminthic infection is also related to protein–energy malnutrition, low pregnancy weight, and intrauterine growth retardation. The most common parasite-causing infections globally are Ascaris lumbricoides (20%), hookworm (18%), Trichuris trichiura (10%), and Entamoeba histolytica (10%).[2]

In 2001, the World Health Assembly passed a resolution urging the Member States to control the morbidity of soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infections through the large-scale use of anthelmintic drugs for school-aged children in less developed countries.[3] The wide spread use of anthelmintic has shown a remarkable reduction in the burden of STH; however, there is a risk of developing drug resistance as a result of frequent treatment with anthelmintic, as there is evidence of widespread drug resistance in the nematodes of livestock who undergo cycles of treatment.[3] Although periodic treatment with anthelmintic for the control of IPI is highly effective and inexpensive, careful study of the epidemiology of STH is needed before making large-scale periodic treatment schedules.[4]

Poor sanitation, scarcity of potable drinking water, and substandard personal hygiene practices may contribute to the rapid spread of such infections.[5] In India, the overall prevalence rate ranges from 12.5% to 66% with the prevalence rate for individual parasite varying from region to region.[6,7,8,9]

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The present study is a descriptive community-based cross-sectional study conducted in 300 randomly selected schoolchildren of Class I to XII (Age group 5–18 years) of government schools located in East Sikkim from January 2016 to December 2016. The institutional ethical clearance was obtained before the study.

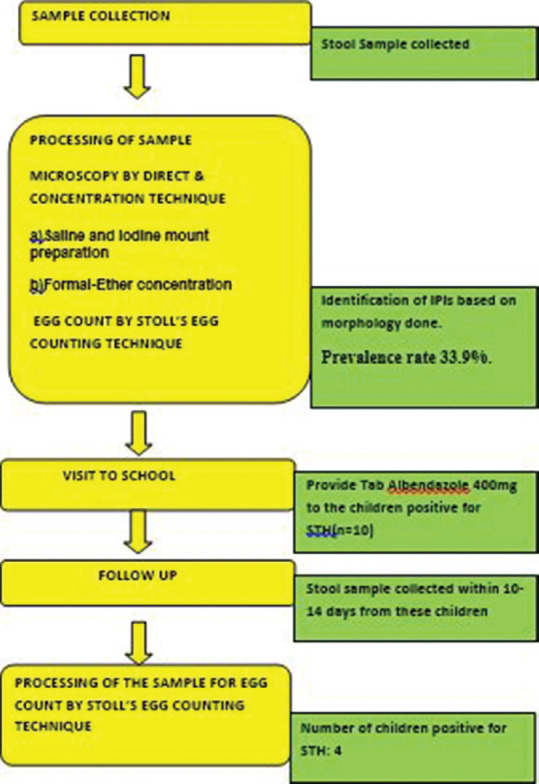

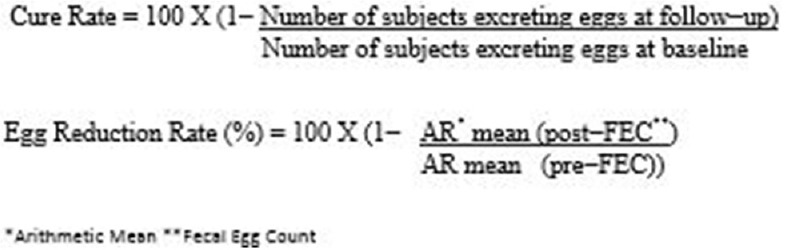

Visit to schools were made and the students counselled and sensitized on the need for stool examination. Consent was taken, stool samples were collected, and the pro forma was filled up. The samples were processed and examined directly by microscopic (saline and iodine mount) and concentration technique (formalin-ether concentration). The samples which were found to be infected with STH were assessed by Stoll's egg counting technique. Follow-up visit: Children infected with STH were given tablet/syrup albendazole (ALB) (Zentel, Glaxosmithkline) 400 mg orally, single dose under the supervision, and the second stool sample was collected again within 10–14 days of consuming ALB. Assessing the egg reduction rate (ERR) by fecal egg count (FEC) reduction test by Stoll's egg counting technique by calculating the total egg count per gram (EPG) of feces was carried out. Finally, the data were analyzed and the results were interpreted [Figure 1]. For drug efficacy, both the cure rate (CR) and ERR were calculated using the quantification techniques.[10] The CR measures the percentage of those treated who become egg negative after drug administration. The ERR measures the percentage reduction in egg intensity after drug treatment using the arithmetic mean (AR) of pre- and posttreatment egg counts [Figure 2]. Interpretation: The efficacy of the treatment for each of the STH was evaluated qualitatively based on the reduction in infected children (CR) and quantitatively based on the reduction in FECs (ERR).[11]

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the steps involved in the study

Figure 2.

Formula used for the calculation of cure rate and egg reduction rate

RESULTS

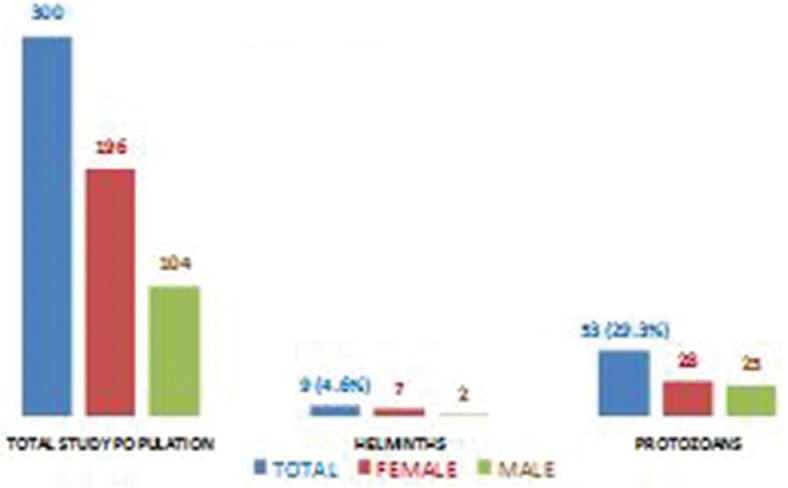

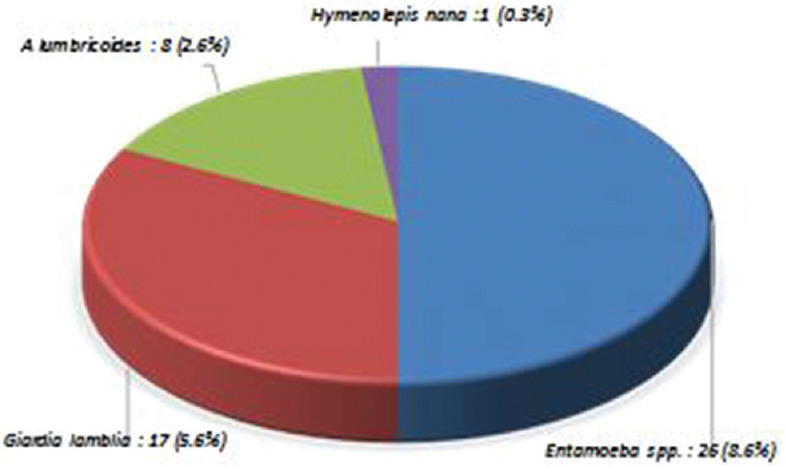

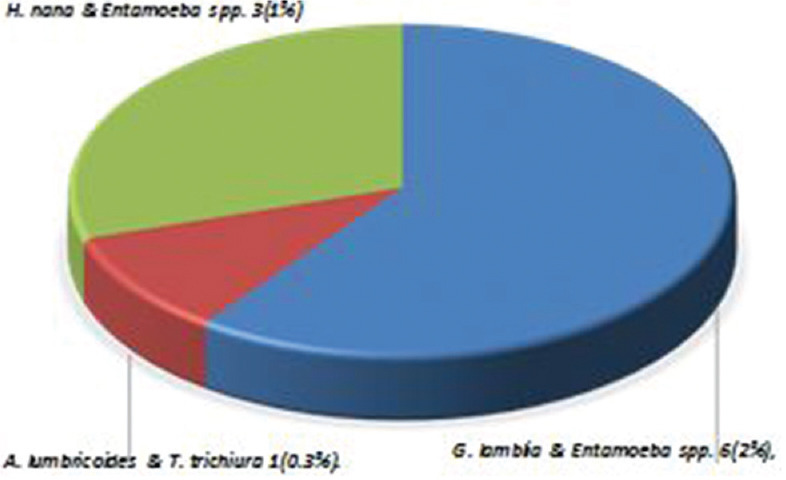

Among the 300 stool samples collected, IPI was found with a prevalence rate of 33.9%. Among various IPIs, protozoans identified were Entamoeba spp. (15.3%) and Entamoeba spp. (14%), and among the helminthes, A. lumbricoides were more prevalent with the prevalence of 3% followed by Hymenolepis nana (1.3%) and T. trichiura (0.3%). The prevalence of protozoan was found more than helminth [Figure 3]. Age-wise distribution showed that in <10 years age group (n = 134), 27 children had IPIs, and in >10 years age group (n = 166), 35 children had IPIs. There were 52 (17.3%) cases of monoparasitic infection such as G. lamblia, Giardia lamblia, H. nana, and A. lumbricoides [Figure 4] and 10 (3.3%) cases of mixed infection with the combination such as G. lamblia and Entamoeba spp., H. nana and Entamoeba spp., and A. lumbricoides and T. trichiura [Figure 5].

Figure 3.

Distribution of intestinal parasitic infections in the study population

Figure 4.

Types of monoparasitic intestinal parasitic infections

Figure 5.

Combination of mixed infections in intestinal parasitic infections

Among the 300 participants, 10 (prevalence 3.3%) children harbored the STH A. lumbricoides and T. trichiura [Table 1]. Examination of stool samples done within 10–14 days post-ALB showed four children still harboring the STH, although the EPG was reduced. EPG pre-ALB in A. lumbricoides ranged from 200 to 1500/g and post-ALB it was 100–600/g, whereas T. trichiura showed a total absence of EPG post-ALB [Table 2]. CR and ERR egg count done by Stoll's egg counting technique pre- and post-ALB showed the reduction in egg count [Table 2].

Table 1.

IPI’s found in the study population

| Name of parasite | Number (Prevalence) |

|---|---|

| Entaemeba spp. | 46 (15.3%) |

| Giardia lamblia | 42 (14%) |

| Hymenolepis nana | 4 (1.3%) |

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 9 (3%) |

| Trichuris trichiura | 1 (0.3%) |

| Total | 102 (34%) |

Table 2.

Egg count of stool samples pre and post treatment with ALB. Cure Rate and Egg reduction rate of IPIs

| Name of the IPIs | Egg count Pre Treatment with ALB | Egg count Post Treatment with ALB | Cure rate | ERR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. lumbricoides | 200-1500/gm | 100-600/gm | 55.5% | 81.4% |

| T. trichiura | 100 gm | 0 | 100% | 100% |

DISCUSSION

Over one billion people in the world are affected by STHs alone, particularly putting school-age (5–15 years) children at risk.[10] The present study revealed the prevalence of IPIs to be 33.9%, with protozoans being more prevalent than helminthes. In the study population, Entamoeba spp. was the most common parasite, followed by G. lamblia., H. nana, A. lumbricoides, and T. trichiura [Table 1]. As compared to other studies[12] conducted in India, the prevalence is low in the present study; the probable reason could be first due to single stool examination and second due to zero open defecation status in Sikkim.

In one study, they found that the hookworm (8.4%) prevalence was high in rural areas, whereas Ascaris (3.3%) and Trichuris (2.2%) were more prevalent among urban children.[13] In the current study, hookworm was not detected in any of the samples; the reason could be that because the study was done in urban children, walking barefoot as in rural children is less in these study populations.

STHs have been identified as a serious public health problem, predominantly among poor communities in the developing world. Benzimidazole (BZ) resistance is widespread and appears to be readily selected in a variety of nematode parasites of animals. There have been reports of a lack of efficacy of BZ anthelmintics against soil-transmitted nematode parasites of humans.[14]

The prevalence of STH was found to be 3.3% with A.lumbricoides infection 3% and T.trichiura infection 0.3%. The prevalence of STH varied widely,[15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] A. lumbricoides infection from 0.6% to 91%, T. trichiura from 0.7% to 72%, and hookworm from 0.02% to 52%. The results obtained in our study are markedly lower than the other states. This may be due to the execution of proper heath control measures in East Sikkim district like ongoing deworming programs for school-age children and no open defecation.

There are a vast number of studies investigating the CRs and ERRs of BZ anthelmintic against human STH; however, many of these are not directly comparable because several of these studies may have been confounded by methodological considerations (e.g., type of diagnostic tests, methods for determining the FEC/ERRs, treatment regimens, drug dosages, and geographical location). Egg count done by Stoll's egg counting technique before and after the consumption of ALB 400 mg single dose showed the reduction in EPG in this study. The reduction was seen more in T. trichiura, followed by A. lumbricoides.

In our study with a single dose of ALB 400 mg, the drug efficacy was high in T. trichiura (CR: 100%; ER: 100%) than A. lumbricoides (CR: 55.5%; ERR: 81.4%). Hall and Nahar[23] had shown that single oral dose of 400 mg ALB gave a CR of <40.0% for A. lumbricoides and T. trichiura in children in Bangladesh. Furthermore, the low CR of ALB against trichuriasis (22.2%) was observed in schoolchildren (ages 4–15 years) in Nigeria with a single dose of ALB against trichuriasis.[24]

The WHO recommended threshold levels for the efficacy of ALB, where an ERR below 70% in the case of A. lumbricoides or below 50% for the hookworms is the currently accepted thresholds.[11] Furthermore, if in chemotherapy-based helminth control programs, the difference of ERR between baseline survey and subsequent monitoring surveys shows a significant decline, the suspicion of drug resistance should be investigated by further tests.[11] A trial was conducted among schoolchildren of seven countries in Brazil, Cameroon, Cambodia, Ethiopia, India, Tanzania, and Vietnam.[25] Efficacy was assessed by the CR and the FEC reduction/ERR using the McMaster egg counting technique to determine FECs. Overall, the highest CRs were observed for A. lumbricoides (98.2%), followed by hookworms (87.8%) and T. trichiura (46.6%). There was considerable variation in the CR for the three parasites across trials (country), by age or the preintervention FEC (pretreatment). They consider ERR the most important than CR for all three STHs. Therapeutic efficacies, as reflected by the ERR, were very high for A. lumbricoides (99.5%) and hookworms (94.8%), but significantly lower for T. trichiura (50.8%), and were affected to different extents among the three species by the preintervention FEC counts and trial (country), but not by sex or age. The study recommended that in future monitoring of single-dose ALB-dependent control programs a minimum ERR of >95% for A. lumbricoides and >90% for hookworms are appropriate thresholds and that efficacy levels below this should raise concern. Thus, in our study, the ERR of 81.4% for A. lumbricoides raises concern and there is a requirement of further study to see the possibility of DR in this region at present. In T. trichiura, ERR is 100%, because there was only one sample which was positive for this parasite; it is difficult to comment on the possibility of the DR.

Such studies have the potential to guide governmental and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to focus their efforts in highly endemic areas. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the prevalence of IPI infections and assess the efficacy of ALB single dose on STH infections.

There is a serious risk that BZ resistance might develop in the future. Priority should be given to accessible diagnosis and treatment of symptomatic individual cases and community-based treatment if morbidity is high and keep monitoring the development of drug resistance.

CONCLUSION

The analysis of collected data provided useful insight into the current prevalence of IPIs in school-going children in government schools in East Sikkim region. The most common IPI prevalent in this region is Entamoeba spp. Among STHs, the most common is A. lumbricoides in the region. Hookworms were not detected in any of the samples; probable reason for this could be due to consumption of deworming tablets in the schools and the study was done in urban population.

As an alternative, mass deworming of schoolchildren and others is now recommended by the World Health Organization – ”The strategy for soil-transmitted helminthiasis control is to treat once or twice per year, preschool and school-age children; women of childbearing age (including pregnant women in the second and third trimesters and lactating women), and adults at high risk, in certain occupations (e.g., tea-pickers, miners, etc.).”[26] In addition, controversies[27] continue, concerning the long-term sustainability of mass deworming – might not sanitary engineering be cheaper in the long run and confer many other health benefits? A recent meta-analysis[28] depressingly concluded, “Deworming drugs used in targeted community programs may be effective in relation to weight gain in some circumstances, but not in others. No effect on cognition or school performance has been demonstrated,” although it has been convincingly argued that this is the result of asking the wrong question in the wrong manner.[29] Such studies have the potential to guide governmental and NGOs to focus their efforts in highly endemic areas. Whatever the best approach is, studies like the ones reported here are needed to remind us of the ubiquity of intestinal parasites and the need to make real progress in reducing this burden on our children's physical and mental development.

Financial support and sponsorship

Research/Thesis Grant for MD/MS students from the North-Eastern Region by DBT.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Mr. Dhurba Bhandari, Laboratory Technician, Sikkim Manipal Institute of Medical Sciences

Ms. N. Onila Nongmaithem, Ph.D., Scholar, Sikkim Manipal Institute of Medical Sciences

Principal, Tadong Senior Secondary School, Deorali Girls Senior Secondary School, Lumsay High Secondary School.

REFERENCES

- 1. [Last accessed on 2018 Nov 01]. Available from: https://www.who.int/intestinal_worms/epidemiology/en/

- 2.World Health Organization. Control of Tropical Diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horton J. Global anthelmintic chemotherapy programs: Learning from history. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:405–9. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(03)00171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fallah M, Mirarab A, Jamalian F, Ghaderi A. Evaluation of two years of mass chemotherapy against ascariasis in Hamadan, Islamic Republic of Iran. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:399–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celiksöz A, Güler N, Güler G, Oztop AY, Degerli S. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in three socioeconomically-different regions of Sivas, Turkey. J Health Popul Nutr. 2005;23:184–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amin AB, Amin BM, Bhagat AP, Patel JC. Incidence of helminthiasis and protozoal infections in Bombay. JIndian Med Assoc. 1979;72:225–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramesh GN, Malla N, Raju GS, Sehgal R, Ganguly NK, Mahajan RC, et al. Epidemiological study of parasitic infestations in lower socio-economic group in Chandigarh (North India) Indian J Med Res. 1991;93:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh P, Gupta ML, Thakur TS, Vaidya NK. Intestinal parasitism in Himachal Pradesh. Indian J Med Sci. 1991;45:201–4, 200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vercruysse J, Albonico M, Behnke J, Kotze A, McCarthy J, Prichard R, et al. Monitoring Anthelmintic Efficacy for Soil Transmitted Helminths (STH), WHO-WB Joint Venture. 2008 Mar [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh S, Raju GV, Samantaray JC. Parasitic gut flora in a North Indian population with gastrointestinal symptoms. Trop Gastroenterol. 1993;14:104–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crompton DW. How much human helminthiasis is there in the world? J Parasitol. 1999;85:397–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar H, Jain K, Jain R. A study of prevalence of intestinal worm infestation and efficacy of anthelminthic drugs. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70:144–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kattula D, Sarkar R, Rao Ajjampur SS, Minz S, Levecke B, Muliyil J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for soil transmitted helminth infection among school children in South India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:76–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prichard RK. Markers for benzimidazole resistance in human parasitic nematodes? Parasitology. 2007;134:1087–92. doi: 10.1017/S003118200700008X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wani SA, Ahmad F, Zargar SA, Dar PA, Dar ZA, Jan TR. Intestinal helminths in a population of children from the Kashmir valley, India. J Helminthol. 2008;82:313–7. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X08019792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ranjan S, Passi SJ, Singh SN. Prevalence and risk factors associated with the presence of Soil-Transmitted Helminths in children studying in Municipal Corporation of Delhi Schools of Delhi, India. J Parasit Dis. 2015;39:377–84. doi: 10.1007/s12639-013-0378-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sehgal R, Reddy G, Verweij J, Rao A. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among school children and pregnant women in a low socioeconomic area. [Last accessed on 2018 Nov 01];Chandigarh North India RIF. 2010 1:100–3. Available from: http://wwwsciencejcom/ri/sehgal_2_1_2010_100_103pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bora D, Meena VR, Bhagat H, Dhariwal AC, Lal S. Soil transmitted helminthes prevalence in school children of Pauri Garhwal District, Uttaranchal state. J Commun Dis. 2006;38:112–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barda B, Ianniello D, Salvo F, Sadutshang T, Rinaldi L, Cringoli G, et al. “Freezing” parasites in pre-Himalayan region, Himachal Pradesh: Experience with mini-FLOTAC. Acta Trop. 2014;130:11–6. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisht D, Verma AK, Bharadwaj HH. Intestinal parasitic infestation among children in a semi-urban Indian population. Trop Parasitol. 2011;1:104–7. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.86946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rashid MK, Joshi M, Joshi HS, Fatemi K. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasites among School Going Children In Bareilly District: Prevalence of Intestinal Parasites Among School Going Children. [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 12];Natl J Integrated Res Med. 2011 2:36–8. Retrieved from: http://nicpdacin/ojs-/indexphp/njirm/article/view/1894 . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pandey B, Kumar D, Verma D. Epidemiological study of parasitic infestations in rural women of Terai belt of Bihar India. Ann Biol Res. 2013;4:30–3. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall A, Nahar Q. Albendazole and infections with Ascaris lumbricoides and Trichuris trichiura in children in Bangladesh. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:110–2. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edelduok EG, Eke FN, Evelyn NE, Atama CI, Eyo JE. Efficacy of a single dose albendazole chemotherapy on human intestinal helminthiasis among school children in selected rural tropical communities. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2013;6:413–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vercruysse J, Albonico M, Behnke JM, Kotze AC, Prichard RK, McCarthy JS, et al. Is anthelmintic resistance a concern for the control of human soil-transmitted helminths? Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2011;1:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO. Intestinal Worms Strategy. [Last accessed on 2011 May 25]. Available from: http://wwwwhoint/intestinal_worms/strategy/en/

- 27.Spiegel JM, Dharamsi S, Wasan KM, Yassi A, Singer B, Hotez PJ, et al. Which new approaches to tackling neglected tropical diseases show promise? PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor-Robinson DC, Jones AP, Garner P. Deworming drugs for treating soil-transmitted intestinal worms in children: Effects on growth and school performance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD000371. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000371.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bundy DA, Kremer M, Bleakley H, Jukes MC, Miguel E. Deworming and development: Asking the right questions, asking the questions right. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]