Abstract

Objective

COVID-19 is a disease with high mortality, and risk factors for worse clinical outcome have not been well-defined yet. The aim of this study is to delineate the prognostic importance of presence of concomitant cardiac injury on admission in patients with COVID-19.

Methods

For this multi-center retrospective study, data of consecutive patients who were treated for COVID-19 between 20 March and 20 April 2020 were collected. Clinical characteristics, laboratory findings and outcomes data were obtained from electronic medical records. In-hospital clinical outcome was compared between patients with and without cardiac injury.

Results

A total of 607 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 were included in the study; the median age was 62.5 ± 14.3 years, and 334 (55%) were male. Cardiac injury was detected in 150 (24.7%) of patients included in the study. Mortality rate was higher in patients with cardiac injury (42% vs. 8%; P < 0.01). The frequency of patients who required ICU (72% vs. 19%), who developed acute kidney injury (14% vs. 1%) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (71%vs. 18%) were also higher in patients with cardiac injury. In multivariate analysis, age, coronary artery disease (CAD), elevated CRP levels, and presence of cardiac injury [odds ratio (OR) 10.58, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.42–46.27; P < 0.001) were found to be independent predictors of mortality. In subgroup analysis, including patients free of history of CAD, presence of cardiac injury on admission also predicted mortality (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.17–5.45; P = 0.018).

Conclusion

Cardiac injury on admission is associated with worse clinical outcome and higher mortality risk in COVID-19 patients including patients free of previous CAD diagnosis.

Keywords: cardiac injury, coronary artery disease, COVID-19, mortality, troponin

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, which causes acute respiratory disease called COVID-19, is a new betacoronavirus and has been named ‘Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome – Coronavirus-2’ (SARS-CoV-2) by the WHO. The disease it causes has been named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and has been characterized as a pandemic since 11 March 2020 [1]. The spectrum of disease can vary from simple cold to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). COVID-19 is also associated with enteric, hepatic, nephrotic, neurological and cardiac involvement causing multiple organ failure and high risk of death [2]. COVID-19 associated mortality rates vary significantly between countries [2,3]. Presence of co-morbid conditions and advanced age are accepted at high-risk indicators in COVID-19 infection [4]. Elevation of high sensitive Troponin I (hs-TnI) which is an indicator of myocardial damage is reported in a significant portion of patients with COVID-19 infection [4–7] but the prognostic value of this finding is not well-defined. In this multicenter study, we aimed to investigate the prognostic value of presence of myocardial damage in patients hospitalized with diagnosis of COVID-19.

Methods

Study population

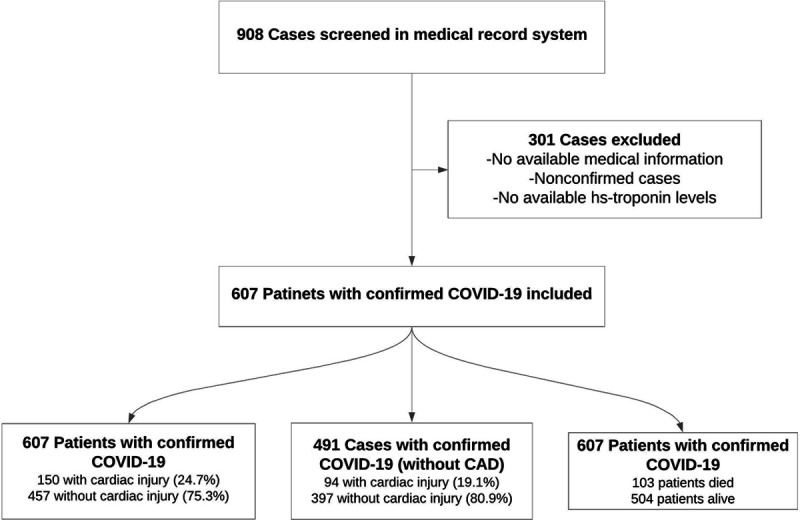

The first COVID-19 case was defined on 11 March 2020 in Turkey. Since then, some government hospitals were modified only to treat COVID-19 patients. For this multi-center retrospective study, data of 607 consecutive COVID-19 patients who were hospitalized in three government hospitals in Istanbul, Turkey between 20 March 2020 and 20 April 2020 were analyzed (Fig. 1). Epidemiological, demographic, clinical, laboratory parameters and outcome data were extracted from electronic medical records of individual hospitals. Patients younger than 18 years of age, with concurrent ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, with history of advanced kidney failure [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 ml/min] or hemodialysis and patients with missing laboratory parameters on admission including hs-TnI, and creatine kinase myocardial band (CK-MB) were excluded. The treatment of each case was left to the discretion of attending physician and was planned according to the national guidelines updated by the Turkish Ministry of Health. This study was approved by the institutional review board and Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study.

Laboratory analysis

Laboratory results of admission complete blood count, routine biochemical parameters including urea, creatinine, blood chemical analysis, assessment of liver and renal function and electrolytes, C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), d-dimer and hs-TnI were collected from medical records. For definition of myocardial damage admission hs-TnI and CK-MB levels were evaluated. The upper reference limit (99th percentile) ranges with an upper reference range of 14 pg/ml for patients.

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) method in the Public Health Microbiology Reference Laboratory of the Ministry of Health. First taking an oropharyngeal swab, then a nasal sample using the same swab and placed on the same transport broth. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) for SARS-CoV-2 virus Routine confirmation of COVID-19 cases was performed by determining specific sequences of virus RNA with a NAAT test such as real-time RT-PCR, and validating it by nucleic acid sequence analysis when necessary.

Definitions and clinical outcomes

The medical records of included patients were searched for development of adverse clinical events including length of stay, development of ARDS, ICU treatment, acute kidney injury (AKI) and mortality. The patients who had no fever and oxygen requirement in the last 48–72 hours and who had a throat-swab specimens SARS-CoV-2 real-time RT-PCR test two times negative were discharged. The last check of individual patient data was performed on 20 April 2020.

Acute cardiac injury was defined as high sensitivity cardiac troponin I serum levels above the 99th percentile upper reference limit, regardless of new abnormalities in ECG [8]. ARDS was defined according to the Berlin definition [9]. AKI was identified according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes definition [10]. The value of initial history chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as eGFR between 30 and 59%/1.73 m2 [11]. Coronary artery disease (CAD) was diagnosed by the presence of documented previous myocardial infarction, or a history of percutaneous coronary intervention/coronary artery by-pass grafting surgery.

The clinical outcomes (AKI, ICU, ARDS, discharges, mortality and length of stay) were monitored up to 20 April 2020, the final date of follow-up.

Statistical analyses

All statistical tests were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 19.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to analyze normality of the data. Continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD, and categorical data are expressed as percentages. Chi-square test was used to assess differences in categorical variables between groups. Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare unpaired samples as needed. The possible factors identified with univariate analyses were further entered into the Cox regression analysis, with backward selection, to determine independent predictors of death. The proportional hazards assumption and model fit was assessed by means of residual (Schoenfeld and Martingale) analysis. Cumulative survival curves were derived according to the Kaplan–Meier method and differences between curves were analyzed on log-rank statistics. Significance was assumed at a two-sided P < 0.05.

Results

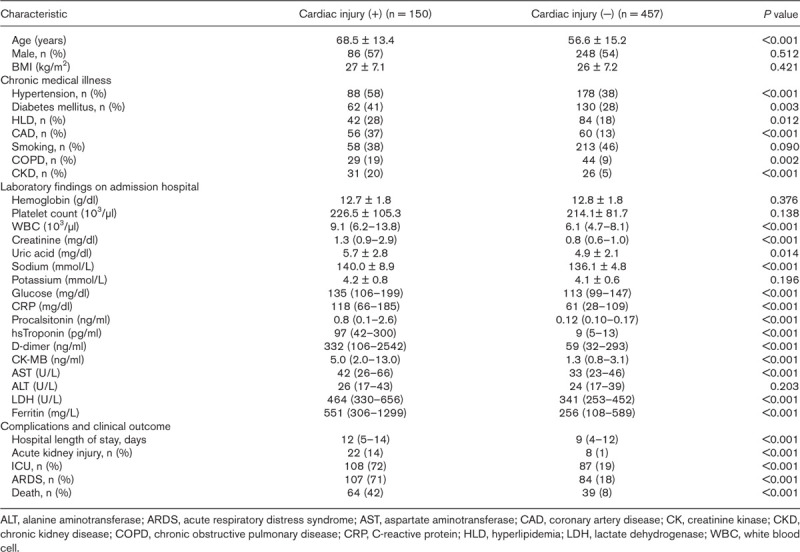

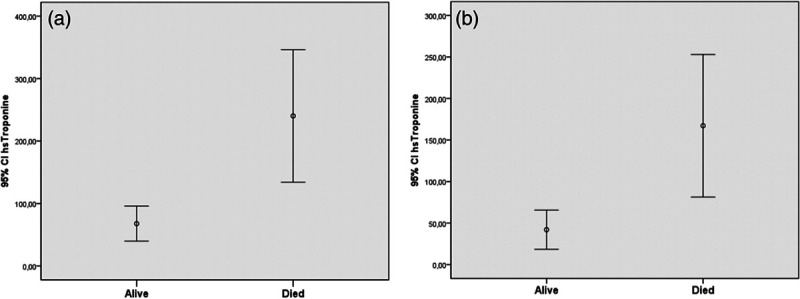

Of the 607 COVID-19 patients recruited for the study, 150 had concomitant cardiac injury on admission. Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with and without cardiac injury are shown in Table 1. Patients with cardiac injury were older and the frequency of patients with CAD, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and CKD was higher in this group. In addition, white blood cells (WBC), creatinine, uric acid, sodium, glucose, CRP, procalcitonin, hs-TnI, d-dimer, CK-MB, AST, LDH and ferritin levels were significantly higher in patients with cardiac injury (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with and without cardiac injury

Fig. 2.

High sensitive cardiac troponin I levels in all patients (a) and without CAD patients (b) who died and survived. CAD, coronary artery disease.

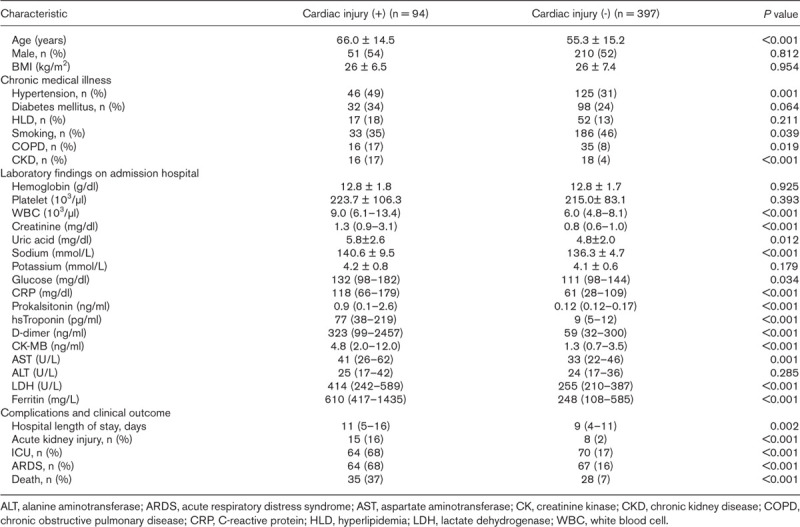

After removing 116 patients with history of CAD, the remaining 491 patients were compared according to the presence of cardiac injury (Table 2). The average age of the group with cardiac injury was statistically higher (P < 0.001). There was a statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of hypertension, COPD and CKD (P < 0.05). Regarding laboratory tests, WBC, creatinine, uric acid, sodium, glucose, CRP, procalcitonin, hs-TnI, d-dimer, CK-MB, AST, LDH and ferritin levels were significantly higher in the cardiac injury group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients without coronary artery disease

The length of hospital stay was longer in patients with cardiac injury. When in-hospital outcomes were compared frequency of patients who required ICU (72% vs. 19%), who developed AKI (14% vs. 1%) and ARDS (71% vs. 18%) and who died (42% vs. 8%) were significantly higher in patients with cardiac injury (Table 1). When patients with previous CAD were excluded, clinical outcome was still worse in patients with cardiac injury, with a mortality rate of 37% vs. 7% (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

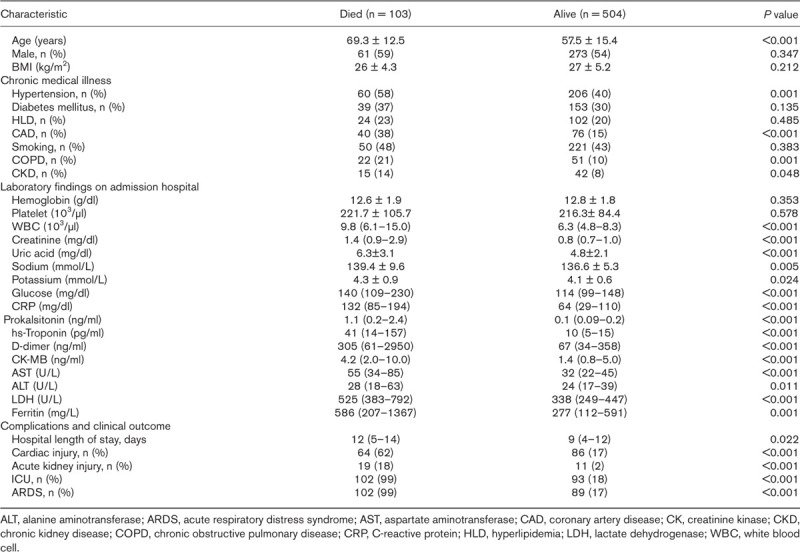

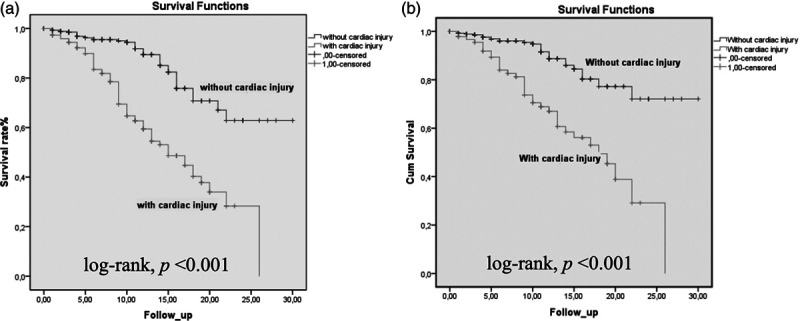

When 103 deceased patients were compared to 504 survived patients, mean age, the frequency of hypertension, CAD, CKD and COPD were significantly higher in deceased group (Table 3). When laboratory tests were compared, WBC, creatinine, uric acid, sodium, potassium, glucose, CRP, procalcitonin, hs-TnI, d-dimer, CK-MB, AST, ALT, LDH and ferritin were statistically higher in deceased patients. The distribution of 103 deaths among groups by day, in the group with cardiac injury, 10.6% of deaths occurred in the first 5 days, 25.2% in the 5–10 days, and 14.5% in the 10–15 days, while in the group without cardiac injury, 11.6% in the first 5 days, 4.8% in the 5–10 days, and 11.6% in the 10–15 days deaths occurred. 50.4% of all deaths were observed in the group with Cardiac injury within the first 15 days (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of patients who died and survived

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for mortality during the time from admission. All patients (a) and patients without coronary artery disease (CAD) (b).

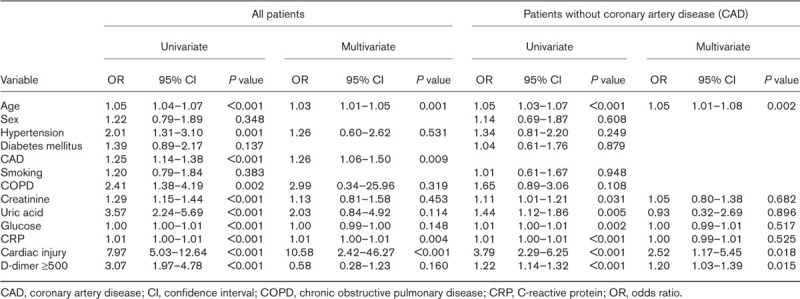

Possible predictors of mortality were evaluated with univariate and multivariate Cox-regression analyses. Clinical and laboratory parameters such as age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, CAD, smoking, COPD, creatinine, uric acid, glucose, CRP, presence of cardiac injury and d-dimer were evaluated in univariate analysis. Age, hypertension, CAD, COPD, creatinine, uric acid, glucose, CRP, presence of cardiac injury and d-dimer ≥500 ng/ml were analyzed in multivariate analysis. Age, CAD, CRP and presence of cardiac injury were found to be independent predictors in terms of predicting mortality [age odds ratio (OR) 1.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01–1.05; P = 0.001; CAD OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.06–1.50; P = 0.009; CRP OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.01; P = 0.004; presence of cardiac injury OR 10.58, 95% CI 2.42–46.27; P < 0.001) (Table 4). When patients with previous CAD were excluded from analyses, presence of cardiac injury was still an independent predictor of mortaliy (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.17–5.45; P = 0.018). When the survival rates were analyzed with Kaplan–Meier survival curves, patients with cardiac injury had significantly higher mortality rates (Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate cox regression analysis on the risk factors associated with mortality in patients with COVID-19

Discussion

In the present study, the prognostic significance of admission hs-TnI levels was investigated in patients with COVID-19. The main findings of our study are as follows:

-

(1)

Cardiac injury was detected in 24.7% of patients included in the study;

-

(2)

The frequency of patients who developed AKI, ARDS, who required ICU treatment and who died was significantly higher in patients with cardiac injury;

-

(3)

In multivariate regression analysis, presence of cardiac injury was found to be an independent predictor of mortality even in patients without history of CAD;

-

(4)

Between fifth and 15th days of hospitalization is a ‘vulnerable period’ for patients with cardiac injury, as most of the deaths occurred in this period.

As of 23 April 2020, the number of cases worldwide is 2.5 million due to COVID-19 infection, and the number of deaths is 165 000. To date, there is no disease-specific treatment or vaccine. COVID-19 with many organ involvement, the most common cause of death in these patients is ARDS and accompanying cardiovascular complications including myocarditis, myocardial injury, arrhythmias, venous thromboembolism, heart failure and cardiogenic shock [2,12–14]. In patients admitted to the emergency department due to COVID-19 infection, both accompanying myocardial involvement, ECG changes due to microvascular damage (ST-elevation, ST-depression and nonspecific ST-T segment changes), and increased cardiac biomarkers (troponin and natriuretic peptide levels) are observed [15].

In a meta-analysis involving 13 studies, cardiac injury is associated with mortality, need for ICU care and severity of disease in patients with COVID-19 [16]. In a another meta-analysis of four different studies, the evaluation of 341 patients showed that high levels of troponin were measured in mortally severe patients compared to mild patients, and increased levels of troponin were associated with mortality [17]. In the retrospective analysis of 191 cases hospitalized for COVID-19 infection; hs-cTnI levels increased in >50% of the deceased patients while the rate of cases measured with hs-cTnI >28 pg/ml was 46% among the deceased patients, only 1% was reported in the survivor patients (P < 0.0001). Significant relationship was found between univariate analysis and hs-cTn I level increase and death (OR 80.1, 95% CI 10.3–620.4; P < 0.0001) [7].

In another study involving 416 patients hospitalized for COVID-19, one in five patients had cardiac injury (19.7%). Invasive-noninvasive mechanical ventilation requirement, ARDS and AKI injury were higher in patients with high troponin levels. Mortality was 10-fold higher in patients with myocardial injury (51% vs. 5%) [6]. In a study by Wang et al. [14], cardiac injury was found to be 16.7%, while in a study by Huang et al. [18], it was found to be 12.1%. Cardiac injury was detected in 24.7% of patients included in our study. AKI, ICU hospitalization, ARDS and mortality rate were higher in patients with cardiac injury compared to those without. hs-TnI levels have a higher OR rate than all laboratory parameters included in both univariate and multivariate analysis. In multivariate analyzes, hs-TnI levels were found to be independent predictors of death in COVID-19 patients with and without CAD. In our study, the reason for the high rate of cardiac injury is that only patients with hs-TnI levels were included.

It is known that d-dimer is an important indicator of mortality in severe infection and sepsis. In a recent study, d-dimer levels were significantly higher in patients who died due to COVID-19 than those who did not die (5.2 µg/ml vs. 0.6 µg/ml, P < 0.0001, respectively). D-dimer >1 µg/ml was found as an independent indicator of in-hospital mortality in multivariate regression analysis (OR 18.42, 2.64–128.55, P = 0.0033) [7]. In our study, d-dimer levels were found to be higher in patients who died compared to the survivors. D-dimer ≥500 ng/ml was determined as an independent predictor of mortality by univariate analysis. D-dimer increase may be due to increased systemic pro-inflammatory activation triggering the prothrombotic process.

Mortality rates are highest in elderly patients with COVID-19 infection (14.8% over 80 years old) and in patients with a history of underlying cardiovascular disease [2]. Similarly, in our study, age and history of CAD were determined as an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality by multivariate analysis.

The cause of the increase in troponin during COVID-19 infection is not fully elucidated. Acute severe respiratory failure syndrome alone may be the cause of increased cTn [19]. In addition, type-I myocardial infarction, which is the result of prothrombotic system activation and plaque rupture triggered by serious inflammatory activation, or type-II myocardial infarction, which is caused due to either increased oxygen demand or decreased supply, as a result of severe myocardial inflammation, are among the possible scenarios [8,12]. In addition, it is suggested that the invasion of ACE-II, which is abundant in myocytes and vascular endothelial cells and is the region where the coronavirus attaches, may cause direct cardiac involvement due to viral myocarditis or stress cardiomyopathy [20]. In severe patients, the imbalance between oxygen demand and supply does not only affect the myocardium, multiple organ failure due to cellular damage may occur. Troponin levels can detect patients with impaired tissue oxygenation and perfusion at an early stage and allow early treatment of these patients.

The comparison of our study and other studies: our study was designed as multicenter and includes more patients than other studies in terms of the number of patients. It is important in terms of demonstrating the prognostic significance of troponin levels observed during the admission in the emergency department. While investigating the effect of cardiac injury in studies on COVID-19, patients with a history of CAD were also included, and the prognostic significance of troponin levels in non-CAD patients was not investigated. Our results demonstrated that the prognostic significance of cardiac injury was shown also in patients without a history of CAD.

In conclusion, it was observed that the cardiac troponin levels, which were found to be high on hospital admission, were associated with worse outcome and predicted in-hospital mortality. Accordingly, increased cardiac troponin levels may reflect the severity of the disease. It is thought that troponin levels frequently increase due to non-coronary events in COVID-19 patients [21] and therefore can be used as a prognostic marker. The clustering of deaths into the first 15 days of the hospital admission in COVID-19 patients has underlined the importance of first 15 days as the critical ‘vulnerable period’ in secondary prevention measures of these patients.

Study limitations

The study was conducted retrospectively, patients whose hs-TnI levels were measured on hospital admission were included in the study. Another limitation of our study is that IL-6 and BNP are not measured and lack of data regarding echocardiography findings. A prospective study involving SARS-CoV-2 infection and involving both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients will provide an accurate estimate of the prevalence of cardiac injury.

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020; 579:270–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou C-Q, He J-X, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:1708–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020; 323:1239–1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C, Chen C, Yan JT, Zhou N, Zhao JP, Wang DW. [Analysis of myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19 and association between concomitant cardiovascular diseases and severity of COVID-19]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2020; 48:E008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020; 368:m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T, Yang F, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 25]. JAMA Cardiol. 2020e200950.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020; 395:1054–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, White H; Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72:2231–2264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, et al. ; ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012; 307:2526–2533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellum JA, Lameire N, Aspelin P, Barsoum RS, Burdmann EA, Goldstein SL, et al. Kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney International Supplements. 2012; 2:1–138 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heywood JT, Fonarow GC, Costanzo MR, Mathur VS, Wigneswaran JR, Wynne J; ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators. High prevalence of renal dysfunction and its impact on outcome in 118,465 patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure: a report from the ADHERE database. J Card Fail. 2007; 13:422–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Libby P, Loscalzo J, Ridker PM, Farkouh ME, Hsue PY, Fuster V, et al. Inflammation, immunity, and infection in atherothrombosis: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72:2071–2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu K, Fang YY, Deng Y, Liu W, Wang MF, Ma JP, et al. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020; 133:1025–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020; 323:1061–1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakkireddy DR, Chung MK, Gopinathannair R, Patton KK, Gluckman TJ, Turagam M, et al. Guidance for cardiac electrophysiology during the coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic from the Heart Rhythm Society COVID-19 Task Force; Electrophysiology Section of the American College of Cardiology; and the Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Heart Rhythm. 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santoso A, Pranata R, Wibowo A, Al-Farabi MJ, Huang I, Antariksa B. Cardiac injury is associated with mortality and critically ill pneumonia in COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lippi G, Lavie CJ, Sanchis-Gomar F. Cardiac troponin I in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): evidence from a meta-analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020; 395:497–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivara MB, Bajwa EK, Januzzi JL, Gong MN, Thompson BT, Christiani DC. Prognostic significance of elevated cardiac troponin-T levels in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e40515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman AR, Bularga A, Mills NL. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin can be an ally in the fight against COVID-19. Circulation. 2020; 141:1733–1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang W, Cao Q, Qin L, Wang X, Cheng Z, Pan A, et al. Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multi-center study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, China. J Infect. 2020; 80:388–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]