Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To compare the risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) among a wide range of ethnoracial groups in the US.

DESIGN

Non-probabilistic longitudinal clinical research.

SETTING

Participants enrolling into the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Unified Data Set recruited via multiple approaches including clinician referral, self-referral by patients or family members or active recruitment through community organizations.

PARTICIPANTS

Cognitively normal individuals 55 and older at the initial visit, who reported race and ethnicity information, with at least two visits between September 2005 and November 2018.

MEASUREMENTS

Ethnoracial information was self-reported and grouped into non-Latino Whites, Asian Americans, Native Americans, African Americans and individuals simultaneously identifying as African Americans and another minority race (AA+), as well as Latinos of Caribbean, Mexican and Central/South American origin. MCI was evaluated clinically following standard criteria. Four competing risk analysis models were used to calculate MCI risk adjusting for risk of death, including an unadjusted model, and models adjusting for non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors.

RESULTS

After controlling for sex and age at initial visit, subhazard ratios of MCI were statistically higher than non-Latino Whites among Native Americans (1.73), Caribbean Latinos (1.80) and Central/South American Latinos (1.55). Subhazard ratios were higher among AA+ compared to non-Latino Whites only in the model controlling for all risk factors (1.40).

CONCLUSION

Compared to non-Latino Whites, MCI risk was higher among Caribbean and South/Central American Latinos as well as Native Americans and AA+. The factors explaining the differential MCI risk among ethnoracial groups are not clear and warrant future research.

Keywords: Mild Cognitive Impairment, race, ethnicity, health disparities

Introduction

Understanding ethnic and racial (ethnoracial) disparities in dementia is a public health priority for the United States (US) (National Institute on Aging, 2018; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2015). Dementia is among the top causes of mortality and morbidity and its costs exceed those of cancer and heart disease (Alzheimer’s Association 2017). Old age is associated with dementia and by 2050, nearly 40% of older adults in the US will be ethnoracial minorities (Ortman et al., 2014). Ethnoracial minorities experience a higher risk for discrimination, lower socioeconomic status, low access to education and geographic exposures, which in turn increase the risk of established risk factors for dementia, including stress, depression, cardiovascular health or low cognitive reserve (Glymour and Manly, 2008). Since mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a precursor of dementia (Alzheimer’s Association 2017), it is imperative to understand whether ethnoracial minorities experience an increased MCI risk.

While the research on ethnoracial disparities in dementia and MCI is growing, the evidence is still limited. Most of the evidence on ethnoracial disparities comes from examining one group in isolation or comparing only few groups (Borenstein et al., 2014; Crane et al., 2009; Evans et al., 2003; Fillenbaum et al., 1998; Foley et al., 2001; Freitag et al., 2006; Gao et al., 2011; Gurland et al., 1999; Haan et al., 2003; Havlik et al., 2000; Hendrie et al., 2014; Louis et al., 2010; Luchsinger et al., 2001; Muller et al., 2007; Perkins et al., 1997; Saczynski et al., 2006; Sanders et al., 2010; Shadlen et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2001; Yaffe et al., 2013). Also, up to recently, very few ethnoracial minority groups had been characterized in dementia research. To address these important limitations, a landmark study compared the dementia incidence among six ethnoracial groups using an exceptionally large sample of healthcare members (Mayeda et al., 2016). The study showed that dementia risk was highest among African Americans (AA), and American Indian/Alaska Natives (AIAN), intermediate for Latinos, Pacific Islanders and non-Latino Whites, and lowest among Asian Americans (AsA). Despite the many strengths, this study presented four limitations. First, participants were healthcare members from Northern California, therefore results might not be generalizable to ethnoracial groups from other US regions. For example, the study was not able to stratify by Latino origin and most California Latinos are of Mexican descent (Ennis et al., 2011). However, some studies suggest that Latinos of Caribbean descent have poorer cognitive and dementia outcomes than those of Mexican descent (González et al., 2014; Gurland et al., 1999). Second, multiracial groups were excluded from the study given small sample sizes. However, there is a growing tendency to have diverse ancestries among Americans (Pew Research Center, 2015). Third, the outcome of dementia diagnosis relied on clinical records. Therefore, diagnosis protocols were possibly not standardized. Fourth, the study did not include educational level, which varies widely among ethnoracial groups in the US (Ryan and Bauman, 2016) and is the modifiable factor with the highest dementia attributable risk worldwide (Norton et al., 2014). This manuscript aims to address important gaps in the literature, including those in the landmark dementia study by analyzing data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Unified Data Set (UDS) protocol. The present study aims to compare the risk of MCI among older adults in different ethnoracial groups in the US. Informed by the literature (González et al., 2014; Gurland et al., 1999; Mayeda et al., 2016), we hypothesize that AA and Caribbean Latinos (but not Mexican Latinos) will have a higher risk of MCI than non-Latino Whites.

Methods

Data source

We used data from the NACC (Besser et al., 2018). NACC maintains the UDS, which includes standardized clinical data reported by past and present NIA-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs) throughout the United States. Each ADC recruits participants according to its own protocols; subjects may come from clinician referral, self-referral by patients or family members, active recruitment through community organizations, and volunteers who wish to contribute to dementia research. Data were collected by clinicians or trained interviewers at each ADC. Assessments were conducted approximately annually. Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the individual ADCs. Centers received approval to gather data at their institutional IRB.

Study sample

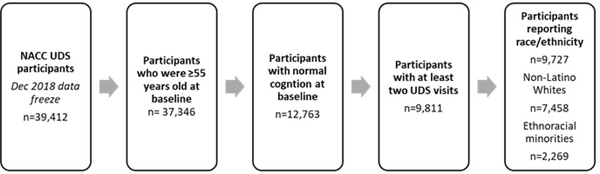

Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the analytic sample which consists of NACC UDS participants with data collected from UDS visits conducted between September 2005 and November 2018. Inclusion criteria for this analysis were the following: 1) 55 years and older at initial visit, 2) clinically diagnosed with normal cognition and CDR® Dementia Staging Instrument global score of 0 at initial visit, 3) a minimum of two UDS visits and 4) reported race and ethnicity. Statistical models only included participants with complete information for the main independent or dependent variables on at least two assessment points. The final analytic sample consisted of 9,727 participants and included 2,269 (23.3%) participants who identified as an ethnoracial minority.

Figure 1.

Sample size flow chart

Measures

Independent variable

Ethnoracial group

The NACC UDS collects data about the participants’ race and ethnicity during the initial visit. The first of three race questions states: “What does the subject report as his or her race?” with seven response options: “1) White, 2) Black or AA, 3) AIAN, 4) Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, 5) Asian, 6) other, and 7) unknown”. The other two race questions state: “What additional race does the subject report?” with the same seven response options plus a “none reported” option. The first of two ethnicity questions ask: “Does the subject report being of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (i.e. having origins from a mainly Spanish-speaking Latin American country), regardless of race?” with answers being “1) yes, 2) no, and 3) unknown”. Only those who reported being Hispanic or Latino responded to a second question that states: “If yes, what are the subject’s reported origins?” with eight options: “1) Mexican, Chicano, or Mexican-American, 2) Puerto Rican, 3) Cuban, 4) Dominican, 5) Central American, 6) South American, 7) Other, (specify), and 8) Unknown”.

Latinos were not categorized in terms of race because the sample sizes for Latinos who identified as Black (n=24) or other races (n=47) were too small to include in our analyses. The low sample size of non-White Latino races is consistent with the literature showing that despite the sizable African and/or American admixture among Latino populations, few Latinos describe themselves as “Black” or “Native American” (Conomos et al., 2016; Humes et al., 2011). Therefore, participants who reported being Latino were collapsed into three groups irrespective of their reported race: 1) Mexican; 2) Caribbean: Puerto Rican, Cuban and Dominican; and 3) Central/South American. Those who did not report Latino ethnicity and reported only White race were categorized as White. Those who did not report Latino ethnicity and reported only a minority race or White plus a minority race were grouped into the minority race they reported. For example, non-Latino individuals who reported White and AA races were considered AA. The grouping of White and another minority race into the minority group was based on the evidence that social categorization of two races in the US still follows the racist rule of hypodescent or the “one-drop” rule (Ho et al., 2011). The rule of hypodescent has its roots in the colonial founding of the US and varied somewhat from state to state, subjugating biracial AA-White individuals to the severe legal and social discrimination faced by their AA ancestors. The social consequences of the rule of hypodescent imply that biracial individuals are assigned the status of their socially subordinate parent group. Therefore, our categorization of race is social, based on historical discrimination of racial minorities that persist to date. Participants could also report race combinations that included two or more minority races. Research suggesting how to operationalize the race of individuals reporting more than one minority race is lacking. In an attempt to operationalize non-Latino participants who report two or more minority races, we grouped them into individuals who simultaneously identified as AA and another minority race (AA+).

Dependent variable

MCI diagnoses were made by a clinician or a consensus team after the examination of all the available information including the CDR, neuropsychological battery, participants’ history and a neurological examination (Morris, 1997; Weintraub et al., 2009). Clinicians were instructed to use the most current criteria for all-cause-dementia at the time of assessment (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Weintraub et al., 2009). Participants with a clinical diagnosis of normal cognition and a CDR global score of 0, were considered cognitively normal. If a participant was not cognitively normal or demented, MCI in all versions was determined based on Petersen’s criteria (Petersen and Morris, 2005). We determined time to first clinical UDS MCI diagnosis using information on their onset. For participants who were cognitively normal and at their next visit had converted to MCI, the onset of MCI was estimated as the median point between the last cognitively normal visit and the first evaluation with MCI diagnosis. For participants who were cognitively normal and at their next visit had converted to dementia, the onset of MCI was estimated as the first quartile point between the last cognitively normal evaluation and the first evaluation with a dementia diagnosis. Participants who did not develop dementia or MCI and did not die while enrolled were censored at their last assessment.

Covariates and descriptive variables

We adjusted models for modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors based on the literature, including age at initial visit, sex, education, living alone, depression, the presence of at least one APOE-e4 allele and a cardiovascular health index (Alzheimer’s Association 2017). Age at first visit was assessed as a continuous variable. Education was categorized as high school or less (0–12 years); some college (13–15 years); graduated college (16 years); or graduate school (17+ years). We used the term “sex” acknowledging that any effect of this variable might be related to either genetic (sex) or social (gender) factors (Unger, 1979). The cardiovascular risk index was the sum of having from zero to four known cardiovascular risk factors at any time point: diabetes (0 no, 1 yes), obesity (0 no, 1 yes), hypertension (0 no, 1 yes) and hypercholesterolemia (0 no, 1 yes). The index is based on knowledge suggesting that cardiovascular risk factors have a cumulative effect on dementia (Pase et al., 2016; Perales‐Puchalt et al., 2019). We described other potential mediators or moderators of the association between ethnoracial groups and MCI including ADC region (South/Midwest US vs West/Northeast), smoking status, and self-reported diagnosis by a clinician of alcohol or other substance abuse, any psychiatric disorder other than depression, B12 deficiency, thyroid disease, cerebrovascular disease and cardiovascular disease.

Statistical Analyses

Sample characteristics of participants at their first visit were described and compared across ethnoracial groups. Comparisons between participants included frequencies, percentages; means and standard deviations as well as the 95% p value of the χ2, ANOVA or Kruskal Wallis. Bivariate associations in risk of developing MCI and death according to ethnoracial groups were described using event incidence per 1000 person-years. Competing risk regression was used to model the association between ethnoracial group and MCI incidence, where competing events (death) that occur prior to or instead of the event of interest cannot be treated as censored (Fine and Gray, 1999). The model estimates a cumulative incidence function, the probability of observing an event before a given time, for the failure event of interest (MCI) while acknowledging the possibility of the competing event (death). Adjusted Model 1 included three confounding non-modifiable risk factors: age at initial visit, sex and clustering by ADC. These factors were considered confounders because they are associated with ethnoracial group and are independent risk factors for MCI but are not in the pathway between ethnoracial group and MCI. Also, standard errors may be affected by ignoring the clustering by ADC (Wei et al., 1989). Adjusted Model 2 added an additional non-modifiable risk factor: APOE e4 carrier status. Adjusted Model 3 added four modifiable risk factors: education, cardiovascular health index, living alone and depression. Years since initial visit were used as the time scale, and the Efron method was used to handle ties in multiple observed event times (Allison, 2010). We also assessed whether associations between ethnoracial group and MCI differed by sex, education and ADC region by assessing interactions. The level of statistical significance for all analyses was set at 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 Software (UCLA: Statistical Consulting Group, 2018).

Results

Among the 9,727 participants included in the final analytic sample, the number of incident MCI cases during follow-up was 1,976. Table 1 summarizes the initial visit characteristics for all participants, by ethnoracial group. Participants’ mean age ranged from 69.9 among AIAN to 73.1 among Whites. There was a higher representation of women in all ethnoracial groups although there were more women in both AA groups (AA and AA+) and Central/South American Latinos (78.8–86.2%) and less among Whites, AsA and Mexican Latinos (63.2–66.4%). Educational level was highest among AsA and Whites (16.7 and 16.2 years) and lowest among Mexican and Caribbean Latinos (12.2 and 13.5). Whites were equally represented by region, whereas both AA groups and Native Americans were more common in the South/Midwest and all other groups were more common in the West/Northeast. Both AA groups, Caribbean and Central/South American Latinos lived alone more often (51.9–67.7%), whereas Whites, AIAN and AsA did so less often (31.9%−36.8%).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at initial visit

| Characteristic | Non-Latinos | Latinos | Total Participants (n=9727) | p-value comparing all 8 groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n=7458) | AA (n=1374) | AIAN (n=105) | AsA (n=232) | AA+ (n=130) | Caribbean (n=133) | Mexican (n=190) | Central/South American (n=105) | |||

| Age, yrs, mean (sd) | 73.1 (8.8) | 71.7 (7.7) | 69.9 (8.3) | 70.4 (7.9) | 70.1 (7.9) | 70.2 (7.2) | 71.2 (7.2) | 70.0 (7.8) | 72.6 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 4710 (63.2) | 1082 (78.8) | 75 (71.4) | 154 (66.4) | 112 (86.2) | 102 (76.7) | 122 (64.2) | 83 (79.1) | 6440 (66.2) | <0.001 |

| Education, yrs, mean (sd) | 16.2 (2.7) | 14.6 (3.1) | 15.1 (2.8) | 16.7 (2.7) | 15.6 (2.6) | 13.5 (4.1) | 12.2 (4.4) | 14.0 (4.0) | 15.8 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Region | ||||||||||

| South/Midwest | 3662 (49.1) | 917 (66.7) | 82 (78.1) | 21 (9.1) | 83 (63.9) | 37 (27.8) | 42 (22.1) | 20 (19.1) | 4864 (50.0) | <0.001 |

| West/Northeast | 3796 ( 50.9) | 457 (33.3) | 23 (21.9) | 211 (91.0) | 47 (36.2) | 96 (72.2) | 148 (77.9) | 85 (81.0) | 4863 (50.0) | <0.001 |

| Lives alone, n (%) | 2741 (36.8) | 843 (61.4) | 36 (34.3) | 74 (31.9) | 88 (67.7) | 69 (51.9) | 79 (41.6) | 56 (53.3) | 3986 (41.0) | <0.001 |

| APOE e4 carrier, n (%) | 1883 (25.3) | 400 (29.1) | 38 (36.2) | 24 (10.3) | 34 (26.2) | 36 (27.1) | 51 (26.8) | 23 (21.9) | 2489 (25.6) | <0.001 |

| BMI, mean (sd) | 26.7 (4.9) | 30.3 (6.3) | 29.4 (6.2) | 24.2 (3.7) | 31.4 (7.0) | 28.8 (5.1) | 29.1 (5.0) | 27.3 (4.7) | 27.4 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Never | 3949 (53.0) | 728 (53.0) | 57 (54.3) | 170 (73.3) | 63 (48.5) | 84 (63.2) | 119 (62.6) | 68 (64.8) | 5238 (53.9) | <0.001 |

| Former | 3220 (43.2) | 531 (38.7) | 46 (43.8) | 62 (26.7) | 49 (37.7) | 42 (31.6) | 62 (32.6) | 35 (33.3) | 4047 (41.6) | <0.001 |

| Current | 219 (2.9) | 105 (7.6) | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (13.1) | 4 (3.0) | 9 (4.7) | 2 (1.9) | 358 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 3629 (48.7) | 694 (50.5) | 59 (56.2) | 116 (50.0) | 70 (53.9) | 80 (60.2) | 100 (52.6) | 46 (43.8) | 4794 (49.3) | 0.051 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 3347 (44.9) | 1010 (73.5) | 61 (58.1) | 108 (46.6) | 97 (74.6) | 72 (54.1) | 107 (56.3) | 50 (47.6) | 4852 (49.9) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 588 (7.9) | 339 (24.7) | 17 (16.2) | 29 (12.5) | 31 (23.9) | 27 (20.3) | 43 (22.6) | 12 (11.4) | 1086 (11.2) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 421 (5.6) | 93 (6.8) | 6 (5.7) | 8 (3.5) | 13 (10.0) | 9 (6.8) | 7 (3.7) | 3 (2.9) | 560 (5.8) | 0.075 |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 1875 (25.1) | 285 (20.7) | 29 (27.6) | 37 (16.0) | 39 (30.0) | 38 (28.6) | 24 (12.6) | 16 (15.2) | 2343 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency, n (%) | 263 (3.5) | 62 (4.5) | 5 (4.8) | 6 (2.6) | 11 (8.5) | 8 (6.0) | 10 (5.3) | 7 (6.7) | 372 (3.8) | 0.014 |

| Thyroid disease, n (%) | 1590 (21.3) | 190 (13.8) | 26 (24.8) | 43 (18.5) | 20 (15.4) | 21 (15.8) | 33 (17.4) | 22 (21.0) | 1945 (20.0) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse, n (%) | 206 (2.8) | 41 (3.0) | 9 (8.6) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (3.1) | 5 (3.8) | 8 (4.2) | 5 (4.8) | 279 (2.9) | 0.005 |

| Other substance abuse, n (%) | 54 (0.7) | 28 (2.0) | 4 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 91 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Total GDS score, mean (sd) | 1.1 (1.7) | 1.1 (1.6) | 1.7 (2.8) | 1.4 (1.9) | 1.6 (1.9) | 1.7 (2.4) | 1.3 (2.2) | 2.2 (2.9) | 1.2 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Depression, n (%) | 1856 (24.9) | 211 (15.4) | 26 (24.8) | 28 (12.1) | 20 (15.4) | 40 (30.1) | 43 (22.6) | 35 (33.3) | 2259 (23.2) | <0.001 |

| Other psychiatric disorders, n (%) | 413 (5.5) | 62 (4.5) | 12 (11.4) | 11 (4.7) | 6 (4.6) | 15 (11.3) | 4 (2.1) | 9 (8.6) | 532 (5.5) | 0.001 |

Bold font indicates p<0.05; AA: African American; AIAN: American Indians and Alaska Natives; AsA: Asian Americans; AA+: Individuals simultaneously identifying as African American and another minority race; BMI: Body Mass Index; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale

There were several differences in clinical variables among ethnoracial groups. AIAN were more often APOE-e4 carriers (36.2%), whereas AsA were least often (10.3%). Body Mass Index was lowest among AsA (24.4) and Whites (26.7) and highest among both AA groups (30.3–31.4). AsA had the highest prevalence of never smoking (73.3%), while Whites, both AA groups and AIAN were the groups with the highest prevalence of current smoking (48.5–54.3%). Generally, Whites, AsA and Central/South American Latinos had the healthiest cardiometabolic indicators’ levels (i.e. lowest prevalence of hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease), whereas both AA groups, AIAN and Caribbean Latinos had the poorest. Vitamin B12 deficiency was lowest among Whites, and AsA (2.6–3.5%) and highest among AA+ and all Latino groups (5.3–8.5%). Thyroid disease was most common among Whites, AIAN and Central/South Americans (21.0–24.8%) and least common among AA (13.8%). Mental health outcomes were generally best for Whites and AsA and poorest for AIAN and Caribbean and Central/South American Latinos.

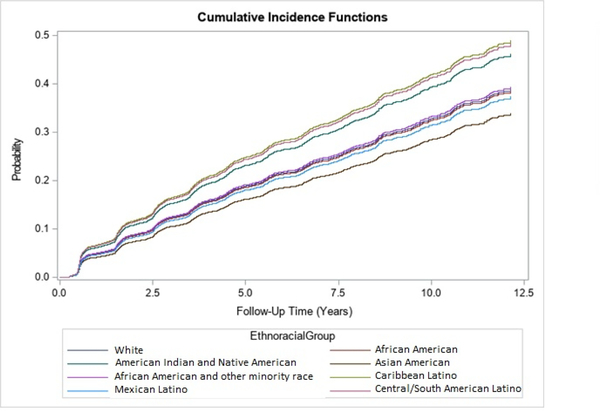

Table 2 shows the number of persons at risk for MCI, the average person-year of follow-up, the number of events and incidence rates of MCI and dementia. Individuals were followed up for 346.1 persons-years (AIAN), 437.5 (South/Central American Latinos), 452.4 (Caribbean Latinos), 561.4 (AA+), 910.1 (Mexican Latinos), 940.8 (AsA), 5974.8 (AA) and 35,611.2 (Whites). The incidence of MCI was highest for Caribbean and South/Central American Latinos and AIAN (54.9–57.5 per 1,000 person-years), moderate for Whites, both AA groups and Mexican Latinos (40.7–44.5) and lowest for AsA (35.1). Mortality rates were particularly high for Whites, both AA groups and AIAN (22.8–32.3 per 1,000 person-years) and lowest for Caribbean Latinos (2.2) and AsA (3.2). Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence function of MCI by ethnoracial groups. In line with the incidence rates reported earlier, the MCI cumulative incidence was highest among Caribbean Latinos and by Central/South American Latinos, followed by AIAN, followed by AA+, Whites, AA and Mexican Latinos, followed by AsA.

Table 2:

Race/Ethnicity and MCI/death events among UDS participants

| Persons at risk | Person-years of follow up | MCI events | Incidence rate per 1,000 person years (95% CI) | Death Events | Mortality rate per 1,000 person years (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Latinos | ||||||

| White | 7458 | 35611.2 | 1553 | 43.6 (41.4, 45.8) | 1152 | 32.3 (30.5, 34.2) |

| AA | 1374 | 5974.8 | 258 | 43.2 (37.9, 48.5) | 136 | 22.8 (18.9, 26.6) |

| AIAN | 105 | 346.1 | 19 | 54.9 (30.2, 79.6) | 9 | 26.0 (9.0, 43.0) |

| AsA | 232 | 940.8 | 33 | 35.1 (23.1, 47.0) | 3 | 3.2 (−0.4, 6.8) |

| AA+ | 130 | 561.4 | 25 | 44.5 (27.1, 62.0) | 16 | 28.5 (14.5, 42.5) |

| Latinos | ||||||

| Caribbean | 133 | 452.4 | 26 | 57.5 (35.4, 79.6) | 1 | 2.2 (−2.1, 6.5) |

| Mexican | 190 | 910.1 | 37 | 40.7 (27.6, 53.8) | 18 | 19.8 (10.6, 28.9) |

| Central/South American | 105 | 437.5 | 25 | 57.1 (4.7, 79.5) | 4 | 9.1 (0.2, 18.1) |

AA: African American; AIAN: American Indians and Alaska Natives; AsA: Asian Americans; AA+: Individuals simultaneously identifying as African American and another minority race; BMI: Body Mass Index; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence curves for risk of any MCI by ethnoracial group

Table 3 shows the unadjusted and adjusted subhazard ratios of ethnoracial groups on MCI. The risk of MCI did not differ statistically between Whites and other groups in the unadjusted model. In the Adjusted Model 1, after adjusting for the three confounding non-modifiable risk factors (participants’ age at initial visit, sex and clustering by ADC), the subhazard ratios of MCI were statistically higher (p<0.05) than Whites for AIAN (1.73) and Caribbean (1.80) and South/Central American Latinos (1.55). The directionality of MCI risk and statistical significance did not change in the other adjusted models except among AA+, who had a statistically higher risk than for Whites when adjusting for all non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors (Adjusted Model 3; subhazard ratio: 1.40, p=0.03). We examined whether associations between ethnoracial groups and MCI differed by sex, education and ADC region. However, no interaction was statistically significant.

Table 3.

Association between risk of MCI and race/ethnicity adjusting for clustering by ADC

| Unadjusted model | Adjusted model 1* | Adjusted model 2** | Adjusted model 3*** | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR | (95% CI) | p-value | SHR | (95% CI) | p-value | SHR | (95% CI) | p-value | SHR | (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Non-Latinos | ||||||||||||

| White | 1.00 | -- | -- | 1.00 | -- | -- | 1.00 | -- | -- | 1.00 | -- | -- |

| AA | 0.99 | (0.87–1.13) | 0.85 | 1.08 | (0.72–1.62) | 0.71 | 1.04 | (072–1.49) | 0.85 | 1.21 | (0.83–1.74) | 0.32 |

| AIAN | 1.26 | (0.80–1.98) | 0.32 | 1.73 | (1.03–2.91) | 0.04 | 1.88 | (1.15–3.07) | 0.01 | 1.72 | (1.02–2.91) | 0.04 |

| AsA | 0.84 | (0.60–1.19) | 0.34 | 1.03 | (0.72–1.48) | 0.88 | 1.14 | (0.77–1.68) | 0.52 | 1.25 | (0.84–1.86) | 0.28 |

| AA+ | 1.02 | (0.68–1.52) | 0.94 | 1.26 | (0.82–1.93) | 0.3 | 1.21 | (0.85–1.72) | 0.29 | 1.40 | (1.03–1.92) | 0.03 |

| Latinos | ||||||||||||

| Caribbean | 1.37 | (0.93–2.01) | 0.12 | 1.80 | (1.17–2.76) | <0.01 | 1.65 | (1.02–2.47) | 0.02 | 1.73 | (1.18–2.56) | <0.01 |

| Mexican | 0.95 | (0.69–1.31) | 0.76 | 1.12 | (0.86–1.46) | 0.4 | 1.12 | (0.84–1.50) | 0.44 | 1.10 | (0.84–1.44) | 0.51 |

| Central/South American | 1.34 | (0.92–1.94) | 0.12 | 1.55 | (1.08–2.24) | 0.02 | 1.70 | (1.10–2.62) | 0.02 | 1.64 | (1.10–2.43) | 0.01 |

Adjusted for clustering by ADC, age at initial visit and sex;

Adjusted for clustering by ADC, age at initial visit, sex and APOE e4 carrier status;

Adjusted for clustering by ADC, age at initial visit, sex, education, cardiovascular health index, living alone, depression and APOE e4 carrier status;

Bold font indicates p<0.05; SHR: Subhazard ratios; AA: African American; AIAN: American Indians and Alaska Natives; AsA: Asian Americans; AA+: Individuals simultaneously identifying as African American and another minority race; BMI: Body Mass Index; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale

Discussion

In this study, we compare the longitudinal risk of MCI between older adults from a wide diversity of ethnoracial groups in the US. We used a large cohort of older adults with clinical characterizations to explore the relationship between ethnoracial groups and the onset of MCI. We hypothesized that AA and Caribbean (but not Mexican) Latinos would have a higher risk of MCI compared to Whites. Our hypothesis was based on ethnoracial minorities’ higher risk for discrimination, lower socioeconomic status, low access to education and geographic exposures, which in turn increase the risk of established risk factors for dementia, including stress, depression, cardiovascular health or low cognitive reserve (Glymour and Manly, 2008). In line with our hypotheses, we found evidence that Caribbean Latinos had a higher MCI risk than Whites. However, we did not find evidence that AA had a higher MCI risk than Whites. Other minority groups with higher MCI risk than Whites were AIAN, South/Central American Latinos and AA+. These differences did not vary by sex, educational level and ADC region.

With exception of AA, our findings are consistent with Mayeda’s landmark study results, where California AIAN (but not AsA and Latinos of predominantly Mexican origin) had a higher dementia risk than Whites (Mayeda et al., 2016). Our findings are also consistent with a limited dementia literature comparing dementia estimates between different studies or few ethnoracial groups at a time, which suggest higher dementia risks than Whites among Caribbean Latinos but not Mexican Latinos and AsA (Gurland et al., 1999; Haan et al., 2003; Luchsinger et al., 2001; Muller et al., 2007; Perkins et al., 1997; Tang et al., 2001). Similarities between our study and other research in dementia ethnoracial disparities may be due to MCI being a precursor of dementia, sharing pathological mechanisms (Alzheimer’s Association 2017). After adjustment for modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors, the risk of MCI remained almost unchanged in most ethnoracial groups in our sample. Other studies have found that the risk of dementia among ethnoracial minorities did not disappear after controlling for non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors (Chen and Zissimopoulos, 2018; Mayeda et al., 2016; Shadlen et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2001).

In line with our hypothesis, the risk of MCI was higher among Caribbean Latinos than Whites. However, Mexican Latinos did not have an increased MCI risk. South/Central American Latinos were also at an elevated MCI risk compared to Whites. These findings are consistent with a limited literature that indicates a phenomenon of Mexican-American Paradox rather than a Latino Paradox, in which Mexican-Americans tend to have health outcomes that “paradoxically” are comparable to Whites, even though Mexican-Americans are more likely to experience discrimination and have lower average income and education (Markides and Eschbach, 2005). The non-differing MCI risk between Mexican Latinos and Whites is consistent with Mayeda's findings in California, in which Latinos and Whites both had an intermediate dementia risk (Mayeda et al., 2016). The higher risk of MCI among Caribbean Latinos is consistent with Gurland’s findings in New York, in which Latinos had a higher risk of dementia and MCI compared to Whites (Gurland et al., 1999). A national population-based study of Latinos also found that Caribbean Latinos performed worse in cognitive tests than Mexican Latinos (González et al., 2014). In this same study, Central American Latinos also performed poorer than Mexican Latinos in two out of five cognitive tests. This difference in MCI risk between Latino groups might be related to Mexican Latinos’ healthier profile in key social, psychological and physiological health characteristics. However, the lack of change in associations after adjusting for different non-modifiable and modifiable factors suggests that their MCI risk difference might be more complex. Mexican Latinos may face different levels of discrimination, and have different coping strategies, social support, cultural values, acculturation, genetic background or environments that protects them from MCI risk more so than other Latino groups in the US. Studies such as the “Study of Latinos-Investigation of Neurocognitive Aging” may shed more light on the differential MCI risk among different Latino groups given their richness of psychosocial, contextual and biomedical assessments.

Dementia disparities research in the US has primarily focused on AA (Evans et al., 2003; Gurland et al., 1999; Mayeda et al., 2016; Perkins et al., 1997; Shadlen et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2001; Yaffe et al., 2013). Many of these studies show that AA have a higher dementia risk when compared to Whites, which sometimes remains even after controlling for other risk factors. Driven by this literature, we hypothesized that AA would have a higher MCI risk compared to Whites in our research. However, our findings showed that the risk of MCI among AA was no different than Whites. Our findings are consistent with Manly (2008), in which New York AA were not at greater risk for development of MCI than Whites. It is possible that AA are at an increased risk of dementia but not MCI. However, this inconsistency with the dementia literature might be related to AA being at a greater risk of developing non-amnestic MCI than Whites, but not amnestic MCI (Katz et al., 2012). In fact, in our overall sample there is a higher proportion of MCI incidence cases being amnestic (79%), but MCI cases among AA are more frequently non-amnestic compared to Whites (28% vs 19%; Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Future studies should explore ethnoracial disparities in MCI subtypes, as they might have different mechanisms and therefore require different risk reduction strategies.

We found that, AA+ had a higher MCI risk compared to Whites when controlling for all risk factors. However, AA+s’ MCI risk was not statistically higher than Whites’ in models that controlled solely for confounders and non-modifiable risk factors. This finding is somehow counterintuitive, as AA+ would be expected to have a higher risk compared to Whites before controlling for risk factors in which they have poorer levels, and have their risk reduced when controlling for those risk factors. However, findings show the contrary. A potential explanation might be that some of those risk factors have a differential effect in Whites and AA+. For example, research has found the effect of early-life social adversity, social engagement and cerebrospinal fluid interleukin 9 to differ between Whites and other ethnoracial minorities including AA (Barnes and Bennett, 2014; Wharton et al., 2019). The higher MCI risk compared to Whites among AA+ but not AA highlights the need to account for the complexity of ethnoracial identities in health disparities research. Accounting for this complexity is especially important given that the US population is becoming more ethnically and racially diverse (Pew Research Center, 2015).

To our knowledge, research has not explored the risk of MCI among AIAN and dementia risk research in this group is limited. In a Canadian study, the age-adjusted prevalence of dementia among indigenous Cree people 65 and older was no different than non-Native English-speaking residents from Winnipeg (4.2% in both groups) (Hendrie et al., 1993). In the US, California insured AIAN had the second highest dementia incidence out of six groups (Mayeda et al., 2016). Our findings are in line with the findings in California and expand the generalizability to MCI risk and AIAN from other US regions, as 78.1% of our sample were the Southern or Midwestern regions. Our study might also be the first to compare the risk of MCI between AsA to other groups in the US. Our findings also showed that the MCI risk of AsA was not different than Whites. These findings are similar to those among California AsA, as AsA where among the groups with the lowest dementia incidence (Mayeda et al., 2016).

This study has several strengths including the use of standard clinical diagnosis protocols to compare MCI risk among multiple ethnoracial groups, and the inclusion of ethnoracial groups such as AIAN, Latino subgroups and AA+ in dementia/MCI research. This study also has some limitations. First, although the NACC UDS is among the largest longitudinal datasets of dementia and cognitive aging characterization in the world, the potential recruitment and retention bias caused by non-probabilistic sampling of the cohort may have influenced our findings. For example, minorities might be recruited more pro-actively than Whites by ADCs due to their well-known barriers to research participation (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2003). This difference in recruitment strategy among ethnoracial groups might lead to a higher MCI risk on behalf of Whites, who might be more likely to come to ADCs due to memory concerns. Alternatively, the difference in recruitment strategy might lead to a lower MCI risk on behalf of Whites who might be more likely to come to ADCs due to their lower access barriers and higher motivation to be healthy and to seek preventative strategies. Second, given the limited formulation of the NACC UDS ethnic and racial background questions, we have not been able to study subgroups that more accurately reflect exposure to MCI risk or protection. For example, AsA is a broad category including ethnic subgroups that may vary widely in MCI risk factors. In Los Angeles County, hypertension prevalence (a risk factor for MCI) among AsA was 23.4%, but varied from 20.0% among Chinese-Americans to 32.7% among Filipino-Americans (Du et al., 2017). Another example would be US Ashkenazi Jewish elders, who have shown to have a later Alzheimer’s disease age of onset than non-Latino non-Jewish Whites and other ethnoracial groups (Duara et al., 1996). Third, modifiable factors such as the cardiovascular health index and depression were operationalized as if they were ever present. However, some of these factors might have a higher effect on MCI at specific ages (Pase et al., 2017), which might be the reason why controlling for these factors barely changed MCI risk estimates.

This study has implications for research and public health policy. The findings showing a higher risk of MCI among some groups in our study suggest that efforts should be made to tailor dementia risk reduction interventions for these groups. It might be too vague to target MCI risk reduction interventions to Latinos in general. Instead, interventions should focus on specific Latino groups, as they have different MCI risk profiles. Our findings also show the need to plan community MCI risk reduction interventions for AIAN, who have been traditionally neglected in this type of research. Studies show that dementia detection among several ethnoracial minorities happens less frequently and at later stages than Whites (Lines and Wiener, 2014). According to our findings, this under-detection is happening to the same groups that have a higher risk of MCI. Medicare annual visits include cognitive screenings to improve MCI and dementia detection in primary care. However, the detection gap between Whites and ethnoracial minorities will likely remain until culturally and linguistically validated tools are mandated. Reducing this detection gap will probably also reduce other gaps including allowing minorities to be part of the decision-making process of their care, reduce behavioral symptoms and improve their and their families’ quality of life. In our study, accounting for modifiable and/or non-modifiable factors did not seem to change the excess MCI risk of most ethnoracial groups. Future studies should explore a wider range of biopsychosocial factors that may account for some groups’ excess MCI risk. When referring to ethnoracial stress for example, aspects such as immigration status, skin color, ethnicity and other minority intersections need to be assessed to account for nativism, racism, ethnocentrism and othering (Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2019). For example, even though most Latinos identify as White race (Humes et al., 2011) their self-rated skin color is associated to experienced discrimination (González-Barrera, 2019). Latinos born in the US experience more discrimination than those born elsewhere (Arellano-Morales et al., 2015). Neighborhood deprivation and literacy levels might also help understand MCI disparities (Letellier et al., 2018; Manly et al., 2003). Including biomarkers such as levels of cortisol over the life course would help achieve a better understanding of the role chronic stress plays in ethnoracial disparities. Ethnoracial discrimination is not solely a US phenomenon. Research in other countries where there are different social constructions of ethnoracial identities may help gain richer perspective about ethnoracial disparities in MCI. Another interesting perspective would be understanding the MCI or dementia risk of individuals whose ethnoracial minority status changed from the country in which they were raised to the country they immigrated to.

Conclusion

We aimed to compare the risk of MCI between older adults from a wide diversity of ethnoracial groups in the US. This study is an advance over earlier and more recent literature, as it examines the risk of MCI, which has been considerably less explored than dementia (Lines and Wiener, 2014; Mateos, 2018). This study also goes beyond examining one group in isolation (Haan et al., 2003; Hendrie et al., 2014), comparing only few groups (Tang et al., 2001; Yaffe et al., 2013) or grouping largely diverse ethnic groups such as Latinos into one category (Gurland et al., 1999; Mayeda et al., 2016). We have found clinically meaningful disparities in MCI among several ethnoracial minority groups. The risk of MCI among Caribbean Latinos and AIAN was substantial and almost doubled that of Whites. The MCI risk among AA+ and Central/South American Latinos was moderate, with an excess risk of 40% and 64% respectively. We found no disparities among Mexican Latinos, AsA and AA. While ethnoracial minorities who had a higher MCI risk than Whites also had a poorer health profile, adjustment for non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors did not account for these differences, complicating the understanding of strategies to reduce MCI disparities among these groups. However, this study provides valuable information suggesting that disparities in MCI follow a similar pattern to disparities in dementia and confirms the differential risk among Latino groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30AG035982, Including a Diversity Supplement awarded to JPP.

Abbreviations

- MCI

Mild cognitive impairment

- ADC

Alzheimer’s Disease Center

- NACC UDS

National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set

Contributor Information

Jaime Perales-Puchalt, University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center, MS6002, Fairway, KS 66205, USA.

Kathryn Gauthreaux, University of Washington, Department of Epidemiology, National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Ashley Shaw, University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center, MS6002, Fairway, KS 66205, USA.

Jerrihlyn L. McGee, University of Kansas School of Nursing, MS 4043, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA.

Merilee Ann Teylan, University of Washington, Department of Epidemiology, National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Kwun CG Chan, University of Washington, Department of Biostatistics, National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Katya Rascovsky, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Department of Neurology, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Walter A Kukull, University of Washington, Department of Epidemiology, National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Eric D Vidoni, University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center, MS6002, Fairway, KS 66205, USA.

References

- Allison PD (2010). Survival analysis using SAS: a practical guide: Sas Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association (2017). 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 13, 325–373. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual-text revision (DSM-IV-TRim, 2000): American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano-Morales L, et al. (2015). Prevalence and correlates of perceived ethnic discrimination in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Journal of Latina/o psychology, 3, 160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes LL and Bennett DA (2014). Alzheimer’s disease in African Americans: risk factors and challenges for the future. Health affairs, 33, 580–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besser L, et al. (2018). Version 3 of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center’s Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders, 32, 351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein AR, et al. (2014). Incidence Rates of Dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and Vascular Dementia in the Japanese American Population in Seattle, WA: The Kame Project. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders, 28, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Dueñas NY, Adames HY, Perez-Chavez JG and Salas SP (2019). Healing ethno-racial trauma in Latinx immigrant communities: Cultivating hope, resistance, and action. American Psychologist, 74, 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C and Zissimopoulos JM (2018). Racial and ethnic differences in trends in dementia prevalence and risk factors in the United States. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 4, 510–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conomos MP, et al. (2016). Genetic diversity and association studies in US Hispanic/Latino populations: applications in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 98, 165–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PK, et al. (2009). Midlife use of written Japanese and protection from late life dementia. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 20, 766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Shih M, Lightstone AS and Baldwin S (2017). Hypertension among Asians in Los Angeles County: Findings from a multiyear survey. Preventive medicine reports, 6, 302–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duara R, et al. (1996). Alzheimer’s disease: interaction of apolipoprotein E genotype, family history of dementia, gender, education, ethnicity, and age of onset. Neurology, 46, 1575–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M and Albert NG (2011). The hispanic population: 2010: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Evans DA, et al. (2003). Incidence of Alzheimer disease in a biracial urban community: relation to apolipoprotein E allele status. Archives of neurology, 60, 185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum GG, et al. (1998). The prevalence and 3-year incidence of dementia in older black and white community residents. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 51, 587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine JP and Gray RJ (1999). A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American statistical association, 94, 496–509. [Google Scholar]

- Foley D, et al. (2001). Daytime sleepiness is associated with 3‐year incident dementia and cognitive decline in older Japanese‐American men. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 49, 1628–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag MH, et al. (2006). Midlife pulse pressure and incidence of dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Stroke, 37, 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Solano N, Coon D and Arean P (2003). Recruitment and retention of Latino dementia family caregivers in intervention research: Issues to face, lessons to learn. The Gerontologist, 43, 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, et al. (2011). Accelerated weight loss and incident dementia in an elderly African‐American cohort. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59, 18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour MM and Manly JJ (2008). Lifecourse social conditions and racial and ethnic patterns of cognitive aging. Neuropsychology review, 18, 223–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Barrera A (2019). Hispanics with darker skin are more likely to experience discrimination than those with lighter skin. Washington DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- González HM, et al. (2014). Neurocognitive function among middle-aged and older Hispanic/Latinos: results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 30, 68–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurland BJ, et al. (1999). Rates of dementia in three ethnoracial groups. International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 14, 481–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haan MN, Mungas DM, Gonzalez HM, Ortiz TA, Acharya A and Jagust WJ (2003). Prevalence of dementia in older Latinos: the influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, stroke and genetic factors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51, 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlik RJ, et al. (2000). APOE-ε4 predicts incident AD in Japanese-American men: The Honolulu–Asia Aging Study. Neurology, 54, 1526–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie HC, et al. (1993). Alzheimer’s disease is rare in Cree. International psychogeriatrics, 5, 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie HC, et al. (2014). APOE ε4 and the risk for Alzheimer disease and cognitive decline in African Americans and Yoruba. International psychogeriatrics, 26, 977–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho AK, Sidanius J, Levin DT and Banaji MR (2011). Evidence for hypodescent and racial hierarchy in the categorization and perception of biracial individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humes KR, Jones NA and Ramirez RR (2011). Overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010.

- Katz MJ, et al. (2012). Age and sex specific prevalence and incidence of mild cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia in blacks and whites: A report from the Einstein Aging Study. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders, 26, 335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letellier N, et al. (2018). Sex-specific association between neighborhood characteristics and dementia: the Three-City cohort. Alzheimer’s & dementia, 14, 473–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lines LM and Wiener JM (2014). Racial and ethnic disparities in Alzheimer’s disease: A literature review. Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Louis ED, Tang MX and Schupf N (2010). Mild parkinsonian signs are associated with increased risk of dementia in a prospective, population‐based study of elders. Movement Disorders, 25, 172–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchsinger JA, Tang M-X, Stern Y, Shea S and Mayeux R (2001). Diabetes mellitus and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with stroke in a multiethnic cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology, 154, 635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y, Vonsattel JPG and Mayeux R (2008). Frequency and course of mild cognitive impairment in a multiethnic community. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society, 63, 494–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Touradji P, Tang M-X and Stern Y (2003). Literacy and memory decline among ethnically diverse elders. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 25, 680–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS and Eschbach K (2005). Aging, migration, and mortality: current status of research on the Hispanic paradox. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, S68–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateos R (2018). Mild cognitive impairment: some steps forward. International psychogeriatrics, 30, 1427–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP and Whitmer RA (2016). Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimers Dement, 12, 216–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC (1997). Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. International psychogeriatrics, 9, 173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, Tang M-X, Schupf N, Manly JJ, Mayeux R and Luchsinger JA (2007). Metabolic syndrome and dementia risk in a multiethnic elderly cohort. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 24, 185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Aging (2018). Goal F: Understand health disparities and develop strategies to improve the health status of older adults in diverse populations Bethersda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K and Brayne C (2014). Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. The Lancet Neurology, 13, 788–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortman JM, Velkoff VA and Hogan H (2014). An aging nation: the older population in the United States: United States Census Bureau, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Department of Commerce. [Google Scholar]

- Pase MP, et al. (2016). Association of ideal cardiovascular health with vascular brain injury and incident dementia. Stroke, STROKEAHA. 115.012608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pase MP, Satizabal CL and Seshadri S (2017). Role of improved vascular health in the declining incidence of dementia. Stroke, 48, 2013–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perales‐Puchalt J, et al. (2019). Cardiovascular health and dementia incidence among older adults in Latin America: results from the 10/66 Study. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins P, Annegers J, Doody R, Cooke N, Aday L and Vernon S (1997). Incidence and prevalence of dementia in a multiethnic cohort of municipal retirees. Neurology, 49, 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC and Morris JC (2005). Mild cognitive impairment as a clinical entity and treatment target. Archives of neurology, 62, 1160–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center (2015). Multiracial in America: Proud, diverse and growing in numbers. Pew Research Center Social & Demographic Trends. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan CL and Bauman K (2016). Educational attainment in the United States: 2015.

- Saczynski JS, et al. (2006). The effect of social engagement on incident dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 163, 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders AE, et al. (2010). Association of a functional polymorphism in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) gene with memory decline and incidence of dementia. Jama, 303, 150–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadlen MF, Siscovick D, Fitzpatrick AL, Dulberg C, Kuller LH and Jackson S (2006). Education, cognitive test scores, and black‐white differences in dementia risk. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54, 898–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M-X, et al. (2001). Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean hispanics, and caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology, 56, 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2015). National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease: 2015 Update.

- UCLA: Statistical Consulting Group (2018). Introduction to survival analysis in SAS.

- Unger RK (1979). Toward a redefinition of sex and gender. American Psychologist, 34, 1085. [Google Scholar]

- Wei L-J, Lin DY and Weissfeld L (1989). Regression analysis of multivariate incomplete failure time data by modeling marginal distributions. Journal of the American statistical association, 84, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub S, et al. (2009). The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 23, 91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton W, et al. (2019). Interleukin 9 alterations linked to alzheimer disease in african americans. Annals of neurology, 86, 407–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, et al. (2013). Effect of socioeconomic disparities on incidence of dementia among biracial older adults: Prospective study. BMJ, 347, f7051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.