Abstract

Background

Genetic defects of pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) provide critical insights into molecular factors controlling intestinal homeostasis. NOX1 has been recently recognized as a major source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in human colonic epithelial cells. Here we assessed the functional consequences of human NOX1 deficiency with respect to wound healing and epithelial migration by studying pediatric IBD patients presenting with a stop-gain mutation in NOX1.

Methods

Functional characterization of the NOX1 variant included ROS generation, wound healing, 2-dimensional collective chemotactic migration, single-cell planktonic migration in heterologous cell lines, and RNA scope and immunohistochemistry of paraffin-embedded patient tissue samples.

Results

Using exome sequencing, we identified a stop-gain mutation in NOX1 (c.160C>T, p.54R>*) in patients with pediatric-onset IBD. Our studies confirmed that loss-of-function of NOX1 causes abrogated ROS activity, but they also provided novel mechanistic insights into human NOX1 deficiency. Cells that were NOX1-mutant showed impaired wound healing and attenuated 2-dimensional collective chemotactic migration. High-resolution microscopy of the migrating cell edge revealed a reduced density of filopodial protrusions with altered focal adhesions in NOX1-deficient cells, accompanied by reduced phosphorylation of p190A. Assessment of single-cell planktonic migration toward an epidermal growth factor gradient showed that NOX1 deficiency is associated with altered migration dynamics with loss of directionality and altered cell-cell interactions.

Conclusions

Our studies on pediatric-onset IBD patients with a rare sequence variant in NOX1 highlight that human NOX1 is involved in regulating wound healing by altering epithelial cytoskeletal dynamics at the leading edge and directing cell migration.

Keywords: IBD, NOX1, ROS, migration

Loss-of-function mutations in human NOX1 result in altered intestinal epithelial reactive oxygen species production. We show that loss of NOX1-mediated reactive oxygen species production is associated with complex alterations of cell migration dynamics important for epithelial wound repair.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a complex and multifactorial disease thought to arise from a combination of environmental factors, epithelial barrier dysfunction, immune dysregulation, and microbial imbalance in genetically susceptible individuals.1 The intestinal epithelium forms a critical barrier that mediates the complex interactions between the intestinal mucosa and the external environment. Oxidative stress responses are important at mucosal surfaces and have been shown to play a role in the pathogenesis and progression of IBD.2 Whereas excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) are considered to cause cellular and organ dysfunction following tissue damage, physiological concentrations of stable ROS molecules such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are crucial for cell signaling.3, 4 Previous studies have shown that H2O2 signaling plays a crucial role in mediating epithelial responses to environmental stress.5

Extracellular ROS production can occur from a number of sources including the membrane-bound NOX family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAPDH) oxidases.6 The NOX enzymes, encompassing 7 major subtypes (NOX1–5, DUOX1, and DUOX2), are expressed in a number of different cell types throughout the body.7 The function of the NOX2 enzyme complex in pathogen killing by surveilling phagocytic cells has been extensively studied. The importance of the NOX2 complex in controlling intestinal homeostasis has been shown by the discovery of patients with chronic granulomatous disease. Loss-of-function mutations in NOX2-complex genes (CYBB, CYBA, NCF1, NCF2, NCF4) cause defective ROS production in phagocytes with increased susceptibility to life-threatening bacterial and fungal infections.8 Notably, a significant number of chronic granulomatous disease patients develop a form of colitis reminiscent of Crohn’s disease.9

In human colonic epithelial cells, a major source of cellular ROS is the NADPH oxidase complex 1, comprising NOX1, p22-PHOX, NOX organizer 1 (NOXO1), NOX activator 1 (NOXA1), and Rac1-GTP.7 Whereas transmembrane NOX1 is the catalytic core of the NADPH oxidase complex 1, the membrane-bound p22-PHOX subunit stabilizes NOX1 and the cytosolic regulatory subunits NOXO1 and NOXA1 regulate NOX1 assembly and activity.7 A number of mouse studies have shown that NOX1 is important for cell proliferation and the fate of progenitor cells in the colon putatively through modulation of PI3K/AKT/Wnt/β-catenin and Notch1 signaling.10 Of note, combined deletion of Nox1 and Interleukin10 (IL10) has been shown to induce chronic endoplasmic reticulum stress in goblet cells and cause ulcerative colitis-like disease in mice.11 Aberrant repair processes in NOX1-deficient mice during experimental colitis were accompanied by impaired proliferation and migration of progenitor cells along the crypt axis.10 NOX1-deficient mice also showed defective wound healing responses in both inflammatory and mechanical superficial ulceration models. Furthermore, NOX1 has been implicated in controlling bacterial pathogenicity, cell matrix adhesion, protection of the epithelial barrier, and secretion of cytokines and immune mediators.12 These mouse studies have demonstrated the critical role of NOX1 in controlling intestinal integrity; however, the exact mechanisms remain poorly defined and context-dependent.

The importance of understanding the role of human NOX1 in intestinal epithelial function has become more critical after the recent identification of children with very-early-onset IBD and inactivating missense mutations in NOX1 and DUOX2.13, 14 These initial studies showed that impaired function of NOX1 results in abrogated ROS production in the intestinal epithelium, although how patient-derived NOX1 mutations affect key ROS-dependent epithelial processes such as cellular migration and wound repair remains incompletely defined. Here we report 2 related patients with pediatric IBD and a stop-gain mutation in NOX1. We demonstrate that loss of NOX1-mediated cellular ROS production is associated with complex alterations of cell migration dynamics, wound healing, and epithelial cytoskeletal function that affect barrier function and repair.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Patient Information and Study Approval

Patients were referred for immunological and genetic workup to the Department of Immunology and Pediatrics at the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Isfahan, Iran, and the Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, Department of Pediatrics, University Hospital, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München in Munich, Germany. Blood samples from patients, relatives, and healthy donor control patients were collected upon informed consent. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, and samples were collected upon informed consent.

Next-Generation Sequencing and Genetic Analysis

Next-generation sequencing was performed as previously described in Kotlarz et al.15 Briefly, genomic DNA from patients and parents was isolated from whole blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A whole-exome library was prepared using the SureSelect QXT Human All Exon V6 +UTR kit (Agilent Technologies, USA). Bar-coded libraries were sequenced in the Illumina Genome Analyzer II (family A) or the Illumina HiSeq 2000 (family B) next-generation sequencing platform with an average coverage depth of ~90x. Short paired-sequence reads were aligned to the human reference genome GRCh37 with Burrows-Wheeler Aligner.16 The Genome Analysis Tool Kit17 was used to analyze whole-exome sequencing data, and functional annotation was performed with snpEff18 and a variant effect predictor using Ensembl19 release 85 (family A) or 71 (family B). Whole-exome sequencing data were filtered and analyzed using an in-house SQL database (family A) or FILTUS v0.0.99–934 (family B).20 Rare variants were identified by incorporating frequency data from the 1000 Genomes Project,18 the NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), and/or ExAC.21 The consequences of filtered variants were predicted with a pack of software, including snpEff,18 VEP,19 SIFT,22 and PolyPhen-2.23 The remaining variants were compiled and filtered for rare mutations following an autosomal inheritance pattern.24 Segregation of the identified NOX1 sequence variant (NM_007052.4:c.160C>T) was confirmed by Sanger sequencing for available family members.

Cloning, Lentiviral Transduction, and Cell Culture

To clone lentiviral constructs under the control of the human spleen focus-forming virus promoter encoding for the NADPH oxidase compounds (NOX1, NOXO1, NOXA1, and p22-PHOX), the human sequence verified cDNA (Addgene 58344, Dharmacon 4661469, 5759212, 3502788) was amplified and subcloned in the third-generation lentiviral vector pRRL using selection marker and primers, as indicated in Supplementary Table 1. The identified mutation in NOX1 (c.160C>T) was introduced in the wild-type cDNA by site-directed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mutagenesis.25 We conducted a PCR-based method using 0.5 μL DpnI per PCR reaction (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and the following primer pair: 5-TGTGCCTGAGCGTCTGCT-3′ and 5-CAACATTGGCCTGTGCCT-3. The cloned lentiviral constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing.

Lentiviral production was performed in HEK293T cells according to previously described protocols.26 Briefly, HEK293T cells were transfected with vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein, pcDNA3.GP0.4xCTE (encoding HIV-1 gag–pol), and lentiviral vectors encoding for the NADPH oxidase compounds with polyethyleneimine (Polysciences, USA) for 12 hours. Supernatants containing viral particles were collected every 24 hours for 72 hours and concentrated by ultracentrifugation. To establish a stable heterologous COS7 cellular model, cells were sequentially transduced with lentiviral particles encoding for components of the multimeric NADPH oxidase complex 1 (p22-PHOX, NOXA1, NOXO1) along with wild-type or mutant (p.54R>*) NOX1 (NOX1wt or NOX1mut). Transduced cells were selected by puromycin (1.5 μg/mL; Invivogen, USA) or flow cytometry–based sorting of the following selection markers: red fluorescent protein (RFP), anti-CD271 (low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor)-PE (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany), and rat anti-mouse CD24-APC (BD Biosciences, USA).

Cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% Pen/strep, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid). The cells were routinely tested negative for Mycoplasma contaminations.

Real-Time PCR

RNA was isolated with the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We generated cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and amplified it by employing real-time PCR using the chemotactic gradient Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and the Step One Plus TM system (Applied Biosystems, USA). Relative mRNA expression was normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and analyzed by the delta-delta-Ct method. The primers are indicated in Supplementary Table 2.

RNAscope

RNAscope in situ hybridization (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, USA) was performed on paraffin-embedded tissue sections per the manufacturer’s instructions. First, 5 μm–thick sections were heated for 1 hour at 60°C and deparaffinized. Samples were next pretreated with H2O2, washed, and incubated with Target Retrieval Solution (Agilent, USA). After short washes with H2O and ethanol, slides were air-dried. Subsequently, slides were treated with Protease Plus Reagent (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, USA), washed, incubated with the specific probe, and washed in wash buffer. Probes for peptidylprolyl isomerase and Bacillus subtilis dihydrodipicolinate reductase were used as positive and negative controls. After hybridization, the Advanced Cell Diagnostics RNAscope 2.0 HD Detection Kit (BROWN) was applied for visualizing hybridization signals.

Determination of ROS Production

ROS production was assessed in heterologous COS7 cells expressing the NADPH oxidase constructs (NOXO1, NOXA1, p22-PHOX, NOX1) using L-012-enhanced chemiluminescence (20 mM, diluted in water; R&D, USA) according to previously described protocols.25 Inhibition of ROS signaling by diphenyleneiodonium (DPI, 10mM; Sigma, USA) served as a negative control, whereas H2O2 (0.05 mM; Sigma, USA) treatment was used as a positive control for ROS production. Baseline ROS and ROS activity in response to phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) 100 nM (Sigma, USA) were detected for 30 minutes each using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader (Synergy H1 Hybrid Multi-Mode Reader, Biotek, USA).

Wound Healing Assay

Wound healing assays were conducted as previously described.27 Briefly, COS7 cell lines were plated in 6-wells and grown to 70%–80% confluence as a monolayer. Next, the cell monolayer was scraped with a sterile 10 μL pipette tip in a straight line to create a “scratch.” Cell migration and closure of the wound were monitored by capturing phase contrast images at indicated intervals.

Migration Studies

Chemotaxis chamber slides (Ibidi μ-Slide Chemotaxis, Ibidi GmbH, Germany) coated with rat-tail collagen-1 were used for both collective and planktonic migration experiments.

For the planktonic migration experiments, 6 μL of 1.5 × 106/mL COS7 cells expressing wild-type and mutant NOX1 (NOX1wt or NOX1mut) were loaded into the center tunnel of each channel and allowed to attach in standard growth media containing FBS for 24 hours. Cells were then serum-deprived for 20 hours. In selected channels, a chemotaxis gradient on one side of the channel was established with a final gradient of 100 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (PeproTech, USA) and 20% FBS. In control channels without a gradient, growth media containing 10% FBS were added to both sides. Chambers were placed in an environmental imaging enclosure (37°C, 5% CO2), and chemotaxis chambers were imaged every 15 minutes for 20–25 hours using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 microscope with a 10X objective. Cell trajectories were analyzed, and Rose plots were generated from captured images using a manual tracking module and the Ibidi Chemotaxis and Migration plugin (Ibidi GmbH, Germany) in ImageJ (NIH, USA). A MatLab routine was used to generate all other data.

For collective migration experiments, 6 μL of 10 × 106/mL NOX1wt or NOX1mut COS7 cells expressing the H2O2-sensitive yellow fluorescent protein HyPer-328 were loaded into the chambers with one of the chamber reservoir loading ports open and the other plugged during cell loading, allowing for the accumulation of cells into one side of the chamber. After 3 hours, media were forced through the center loading chamber, causing cells attached in the center of the channel to detach and leaving only cells accumulated to one side. A chemotactic gradient was established as described in the paragraph above using 20% FBS and 5 μM formyl-methyl-leucine-phenylalanine (fMLF). Time-lapse images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 880 Airyscan microscope for 48 hours with images taken every 15 minutes. A custom MatLab analysis routine was used to analyze collective migration data. A cell front border was manually drawn at time 0. The cell front border was binned into 6.5 μm sections in the y axis (around the size of a single cell) and measured as a function of time. The average position of the cell front was calculated by averaging the distance moved by all individual bins, and the histogram analysis was calculated from individual bins.

Immunohistochemistry/Immunofluorescence

COS7 cells with NOX1wt or NOX1mut were seeded onto 24-well plates with coverglass bottoms (Cellvis, Mountain View, CA) and grown to near confluency (>95%). A monolayer scratch wound in a cross pattern was made using a pipette tip on a Pasteur pipette connected to a vacuum pump. Media were replaced and cells allowed to migrate for 6 hours. Cells were fixed (4% paraformaldehyde), permeabilized (0.1% Triton X-100), and blocked (Odyssey Blocking Buffer, Li-Cor; 15 minutes). Primary antibodies for rabbit anti-human phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (p-FAK), rabbit anti-human p22-PHOX (Abcam), mouse anti-human p-P190 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rhodamine-phallodin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were added and incubated overnight at 4°C. Samples were then washed and secondary antibodies of anti-rabbit Alexa 488 and anti-mouse Alexa 647 (diluted in Odyssey Blocking Buffer) were added and incubated overnight in 4°C conditions. Next, all samples were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and then left in PBS for imaging.

Paraffin-embedded sections from biopsies of NOX1-deficient patients or normal uninflamed and inflamed tissues from patients with ulcerative colitis were deparaffinized, rehydrated, blocked (10% goat serum), and incubated with primary antibodies for mouse anti-human p-P190, DAPI (4′,6-diamidine-2′-phenylindole dihydrochloride), and rabbit anti-human p-FAK overnight at 4°C, washed, and incubated with anti-rabbit Alexa 488 and anti-mouse Alexa 647.

Cells and tissues were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 880 Airyscan microscope using 40X and 60X objectives. Representative cell images (3–5 per well) were taken from multiple (>4) wells with both wound edge and cells within the body of the monolayer.

For analysis of protrusions at the wound edge, a custom MatLab program was used to identify and count protrusions on the cell edge. The frequency of protrusions was calculated based on the number of protrusions divided by the exposed cell perimeter, assuming a smooth line to measure the cell perimeter. Frequency was expressed as the mean distance between protrusions. For analysis of p22-PHOX fluorescence, regions of interest were assigned to protruding “leader” cells (defined by cells ahead of the average migrating edge) and “follower” cells (defined by cells behind the average migrating edge). Mean fluorescent intensity was measured using ImageJ software (NIH) from 12 regions per image, 9 images per experiment.

Statistics

Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for each treatment group. Statistical comparisons were performed using either the 2-tailed Student t test or an ANOVA with the Tukey multiple-comparison posthoc test. The P values that were < 0.05 were considered significant (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

RESULTS

Identification of a Stop-Codon Mutation in NOX1 in Patients With Pediatric-Onset IBD

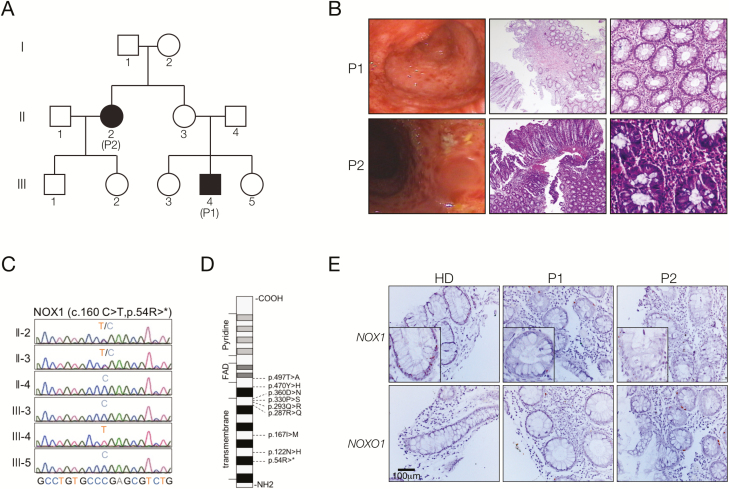

Our 21-year-old index patient 1 (referred to as P1 or III-4) was born to a non-consanguineous family of Iranian origin and presented with early onset of IBD at age 8. Notably, his 42-year-old aunt (patient 2, referred to as P2 or II-2) also developed IBD symptoms at age 5 (Fig. 1A). Both P1 and P2 presented with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and rectal bleeding. Endoscopy confirmed the diagnosis of colitis with ulcers in the descending and transverse colon (Fig. 1B). Histology revealed colonic mucosal distortion, polymorphic infiltration, cryptitis, and crypt abscesses (Fig. 1B). In addition, both patients also had significant esophagitis with ulceration. Both patients were refractory to therapy with standard anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive treatments, including mycophenolate, prednisolone, and mesalazine. Extraintestinal manifestations of P1 included hemolytic anemia, hypothyroidism, autoimmune hepatitis, and cirrhosis.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of patients with pediatric-onset IBD and a stop-gain mutation in NOX1. A, Pedigree of the index family with 2 affected patients (II-2; III-4). B, Colonoscopy showed chronic pancolitis with ulcers in the descending and transverse colon. Histological examination revealed mild mucosal inflammation, increased epithelial de- and regeneration, crypt hyperplasia, and distortion. C, Sanger sequencing confirmed the identification of the hemizygous stop-gain mutation in NOX1 in patient III-4. D, Scheme of the NOX1 protein indicating the novel stop-gain and previously published13, 14 mutations in NOX1. E, RNAscope analysis showed decreased NOX1 and normal NOXO1 expression in colonic biopsies of patients II-2 (P2) and III-4 (P1) as compared with healthy donors (HD; n = 2).

To elucidate the molecular etiology in our patients, we conducted whole-exome sequencing, which revealed a rare novel hemizygous stop-gain mutation in the transmembrane region of NOX1 (ENST00000372966.7, c.160C>T, p.54R>*; Figs. 1C, D). Sanger sequencing confirmed segregation with the disease phenotype in P1 because the mother (patient II-3) showed a heterozygous genotype and the father (II-4) and his siblings (III-3, III-5) showed a wild-type genotype (Fig. 1C). His aunt, P2, showed a heterozygous genotype for the NOX1 mutation. Heterozygous carriers of X-chromosomal mutations are usually healthy, but nonrandom X-chromosome inactivation has been previously reported in diseased female patients with infectious or autoinflammatory manifestations.29 We could not test this hypothesis because of a lack of patient material, but an RNAscope on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded colonic biopsies of P1 and P2 showed a decreased mRNA expression of NOX1 in the colon compared with that of healthy donors (Fig. 1E).

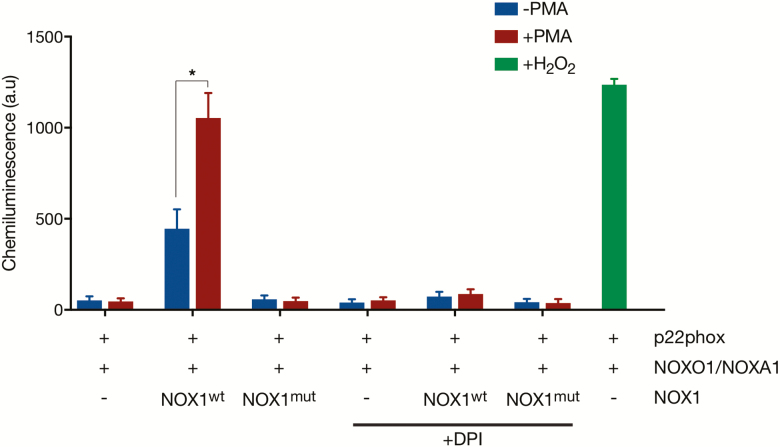

Defective ROS Production in NOX1-Deficient Cells

Deletion of NOX1 has been shown to increase epithelial stress and susceptibility to colitis in mice.10 Correspondingly, loss-of-function mutations in human NOX1 have been recently reported to reduce epithelial ROS production and to predispose to colonic inflammation.13, 14 To confirm that the newly identified mutation in NOX1 leads to defective ROS activation, we generated heterologous COS7 cells with lentiviral-mediated overexpression of the NADPH oxidase 1 components p22-PHOX, NOXO1, and NOXA1 along with either wild-type or mutant NOX1 (NOX1wt or NOX1mut). COS7 cells were used as a heterologous model because of a lack of expression of the multimeric NADPH oxidase complex 1 and undetectable endogenous ROS production (Supplementary Figure 1).13 Whereas overexpression of NOX1wt induced a substantial superoxide production in COS7 cells under normal cell culture conditions and after stimulation with PMA, we could not detect increased ROS activity in cells expressing NOX1mut or in control cells (untransduced or RFP-transduced cells) (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

The identified NOX1 mutation is associated with altered ROS activity. An L-012 chemiluminescence assay showed that COS7 cells expressing mutant (mut) NOX1 (p.54R>*) exhibit reduced ROS activity at baseline and after PMA stimulation in comparison to cells with wild-type (wt) NOX1. ROS signaling was inhibited by DPI (10 mM; Sigma, USA), whereas external addition of H2O2 (0.05 mM; Sigma, USA) treatment was used to induce ROS production. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 experiments. *P < 0.05.

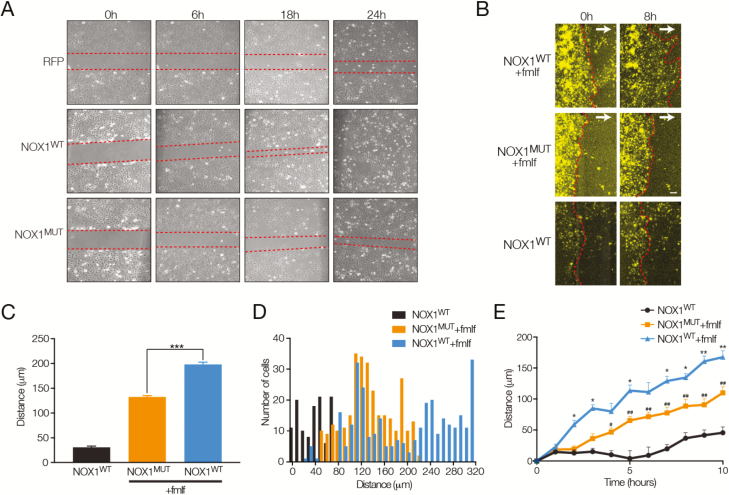

NOX1 Deficiency Is Associated With Delayed Wound Healing and Altered Collective Cell Migration

ROS has been suggested to play an essential role in wound repair and regeneration by modulating inflammation, cell proliferation, migration, and extracellular matrix synthesis and deposition. Accordingly, Kato et al.30 have shown that NOX1-deficient mice exhibit defective intestinal mucosal tissue repair in an experimental colitis model. Using an in vitro scratch assay, we found delayed wound healing in cells with NOX1mut as compared with cells expressing NOX1wt (Fig. 3A). Treatment with DPI, a potent NOX inhibitor irreversibly reacting with the NADPH oxidase, reduced wound healing in cells with transgenic expression of NOX1wt, suggesting that altered wound repair in the absence of functional NOX1 results from defective ROS production.

FIGURE 3.

Impaired collective migration in NOX1 deficiency. A, Scratch wound assay in COS7 cells with expression of RFP, NOX1 wild-type (NOX1wt), and the patient-specific NOX1 mutant (NOX1mut). Representative images showing wound margin (red dotted lines) at 0, 6, 18, and 24 hours post–scratch wound. B, Fluorescence images showing NOX1wt and NOX1mut cells migrating toward a concentration gradient of fMLF and FBS (5 μM and 20% gradient direction indicated by white arrows) or NOX1wt without any gradient. C, Summary data showing mean total distance moved of the migrating front in 8 hours after establishment of a chemotactic gradient, mean ± SEM, n = 3 experiments. ***P < 0.001. D, Histogram analysis showing distance moved of individual cells at the front of the migrating edge in NOX1wt and NOX1mut cells, n = 3 experiments. E, Time course of migrating front movement showing distance moved against time for NOX1wt and NOX1mut cells in the presence of a chemotactic gradient or for NOX1wt cells without gradient, mean ± SEM, n = 3 experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, NOX1wt + fMLF and FBS gradient versus NOX1mut fMLF and FBS gradient; #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01, NOX1mut fMLF and FBS gradient versus NOX1wt without gradient.

Wound repair and restitution of epithelial cell surfaces rely on a number of cellular processes including robust 2-dimensional chemotactic migration of epithelial cells.31 To define the contribution of a loss of NOX1-mediated ROS production in cell migration we looked at both collective monolayer and single-cell (planktonic) migration in NOX1wt and NOX1mut cells in the presence or absence of a chemokine gradient. Using formyl peptide (fMLF) and FBS as chemoattractants, we observed a significant attenuation in the average collective migration in NOX1mut cells over time (Figs. 3B–D). Histogram analysis of the movement of cell fronts showed a single population of NOX1mut cells with reduced mobility (Fig. 3E). Interestingly, analysis of NOX1wt cells revealed 2 distinct populations of cells, one with distances moved similar to NOX1mut or untransfected cells and another with considerably increased migration distances.

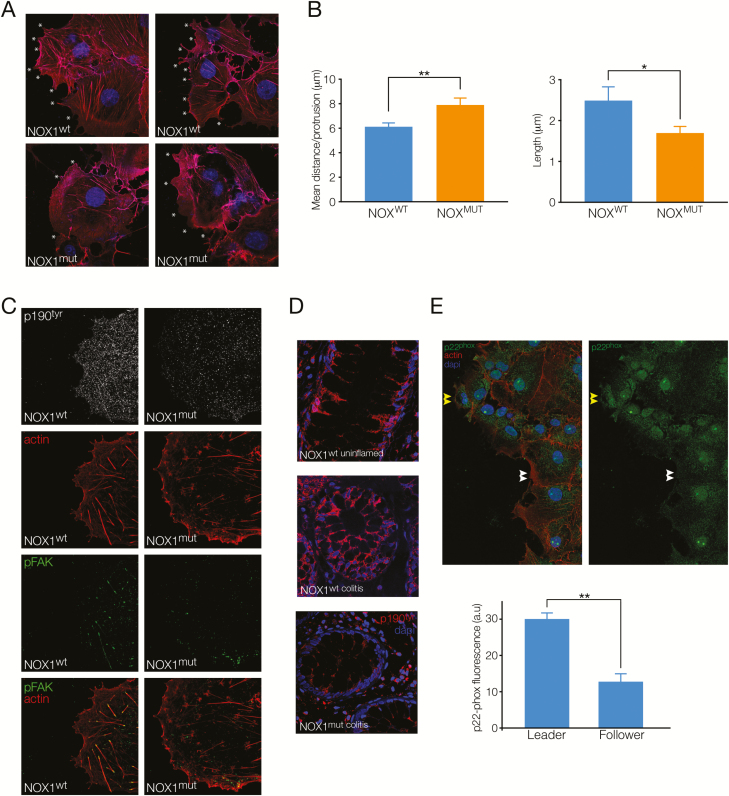

Cytoskeletal Changes and Subcellular Protrusions at the Wound Edge in NOX1-Deficient Cells

Our collective migration data suggested that the patient-derived NOX1 mutation leads to impaired cellular migration. Previous data have implicated a role for the Rho-Rac pathway in ROS-mediated regulation of cell shape and migration via phosphorylation of the Rho-GAP protein P190cas32 and focal adhesions via p-FAK.12 To assess whether the NOX1mut causes changes to these cytoskeletal proteins, we carried out high-resolution microscopy of wound edge cells and regenerating crypts in colonic biopsies from our NOX1-deficient patients. Actin staining revealed an increased distance between lamellipodial and filopodial protrusions (reduced frequency) and shorter small filopodial protrusions at the wound edge in NOX1mut patient cells as compared with NOX1wt cells (Figs. 4A, B). Immunostaining for phosphorylated (active) p190 showed reduced intensity of membrane-bound staining in NOX1mut cells and colonic crypts (Figs. 4C, D). Correspondingly, NOX1mut cells showed p-FAK at focal adhesion sites dispersed in the cell, whereas NOX1wt cells exhibited active focal adhesions with distinct punctate p-FAK staining at the end of F-actin fibers at the base of wound edge cells (Fig. 4C). Because we found a population of NOX1wt cells with enhanced migration, we assessed expression of the NOX1 complex by p22-PHOX staining in leading edge cells. As shown in Fig. 4E, advanced cells at the leading edge showed a higher expression of p22-PHOX compared with adjacent cells, suggesting that expression of the NOX1 complex is increased in epithelial “leader” cells versus “follower” cells.

FIGURE 4.

NOX1 function is important for cell protrusions and cytoskeletal dynamics at the migrating edge of cells. A, Images showing actin staining (red) and nuclei (blue) indicate filopodial and lamellapodial protrusions (white asterisks) at the wound edge of NOX1wt and NOX1mut COS7 cells in scratch wound healing assays. B, Summary graph showing protrusion density (mean distance between protrusions) and protrusion length, mean ± SEM, n = 4 experiments, 40–50 cells analyzed/experiment. **P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (C) Images showing NOX1wt and NOX1mut cells at the wound edge stained for phosphorylated p190tyr (white), actin (red), pFAK (green), and composite image of actin and pFAK staining. D, Immunohistochemical images of colon tissue from a control patient without inflammation (NOX1wt uninflamed), a control patient with colitis (NOX1wt colitis), and a patient with an NOX1 stop-gain mutation (NOX1mut colitis), stained for phosphorylated p190tyr (red) and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Images representative of 3 stained sections and 5–8 images/section. E, Top, Images showing cells at the wound edge in NOXwt cells stained for p22-PHOX (green), actin (red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue) on the left and p22-PHOX (green) only on the right. Bottom, Summary graph showing p22-PHOX mean fluorescence (arbitrary units) in migrating leader cells versus follower cells in NOXwt cells, n = 3 experiments, 9 images analyzed/experiment.

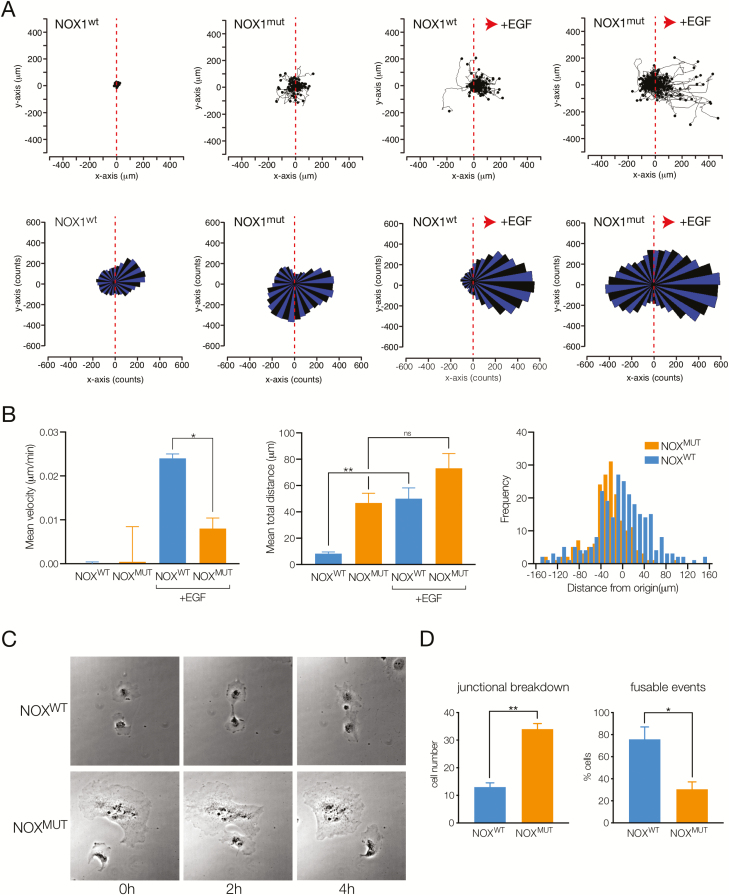

NOX1 Deficiency Is Associated With Altered Planktonic Cell Migration With a Loss of Directionality

Collective migration of monolayers is a complex process involving coordinated migration of cells with communication between adjacent cells via cell junctional proteins and between cells at the front of the migrating edge and those behind via focal adhesions to the underlying matrix.31 The action of leader cells directing collective migration at wound edges is thought to be important for efficient wound healing.33 Our finding of a population of NOX1wt cells with faster movement and increased expression of p22-PHOX in advanced cells led us to examine the role of the functional NOX1 complex in single-cell migration. Analysis of individual tracks of NOX1wt and NOX1mut cells in the absence of a chemotactic gradient (Fig. 5A, left) revealed that cells migrated equally in either direction, as illustrated by the corresponding vector rose plots (Fig. 5A, bottom). NOX1mut cells showed significantly increased total distance moved as well as nondirectional velocity (Fig. 5B). The increased total velocity and distance moved persisted in the presence of a chemotactic gradient (Fig. 5A, right). However, NOX1mut cells continued to migrate equally in both directions with loss of directional migration toward the chemokine (epidermal growth factor), whereas NOX1wt cells showed robust and specific vectorial migration (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Defective directional planktonic migration and cell-cell contacts with loss of NOX1 function. A, Top, Cell tracking plots showing individual cell movement relative to their starting position for NOX1wt and NOX1mut cells at baseline (left) and in the presence of a chemokine gradient (epidermal growth factor, 1 μM) toward the positive x axis (right, indicated by red arrow). Bottom, Rose plots of single-cell migration data showing vectorial movement of cells. B, Left, Mean velocity of cells in positive x-direction (gradient direction), mean ± SEM, n = 3 experiments. *P < 0.05. Middle, Mean total distance moved for cells (in any direction), mean ± SEM, n = 3 experiments. **P < 0.01. Right, Histogram analysis of distance moved from origin in the x-direction. C, Brightfield images showing example of NOX1wt and NOX1mut cells moving and contacting over 4 hours. D, Summary graph indicating number of cells undergoing junctional breakdown (cells meeting and continuing to migrate separately) and percentage of cells with fusable events (cells meeting and migrating together), mean ± SEM, n = 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

To investigate further how cells move in the presence or absence of functional NOX1 complexes, we assessed cell spreading and cell-cell interactions. During single-cell migration experiments, cells occasionally interact with neighboring migrating cells. We assessed these interactions by measuring the percentage of cells that contacted other cells and remained in contact during the period of measurement (“fusable events”) and the percentage of cells that were already in contact but lost cell-cell contacts (“junctional breakdown”). As shown in Fig. 5D, NOX1mut cells showed fewer fusable events along with more cells breaking cell-cell contact, corresponding to our observation that NOX1mut cells have increased but nondirected movement.

DISCUSSION

Our study on patients with a stop-gain mutation in NOX1 confirmed that human NOX1 is a critical mediator of intestinal ROS production and provided novel mechanistic insights on wound healing and directional cell migration.

The association between an altered redox environment and the progression of inflammation in the intestine and other mucosal surfaces has been well established, although the majority of studies have largely focused on the presence of excessive concentrations of unstable free radical species in the setting of chronic inflammation or acute highly damaging insults.34 Emerging evidence has shown that stable ROS is also critical in controlling cell signaling during intestinal homeostasis.4, 5 In intestinal epithelial cells, NOX1-generated ROS has been proposed to play a variety of roles in epithelial restitution, including involvement in epithelial proliferation, migration, and differentiation.35 The finding that germline mutations in NOX1 and the related enzyme DUOX2 are associated with early-onset colonic inflammation suggests that NOX1 has an important role in controlling the homeostasis of the colonic mucosal barrier.13, 14

Similar to previously reported patients with missense mutations in NOX1,13, 14 our patients with a deleterious stop-gain mutation presented with early-onset IBD with ulceration and disruption of the colonic epithelium. In vitro biochemical assays confirmed that the mutation led to near-complete loss of ROS production. Following numerous reports showing a role for ROS in wound healing and cell migration, we investigated the effects of NOX1 deficiency on the dynamics of cell migration. Our cell biological studies showed that loss of NOX1 led to alteration in wound healing responses and the dynamic structure of migrating cells at the leading edge. Signaling through Rho family GTPases (e.g., Rac, Cdc42, and Rho) is crucial for cell migration.32 Activated Rac and Cdc42 are involved in the production of lamellipodia and filopodia, and Rho activation stabilizes protrusions by stimulating the formation of mature focal adhesions and stress fibers.36 Phosphorylation of p190A Rho-GAP is important in the regulation of Rho activity and the formation of focal adhesions.37 Abrogation of NOX1-generated ROS by small-interference RNA or DPI has been shown to restore RhoA activation, leading to disruption of both actin stress fibers and focal adhesions in Ras-transformed cells, and impair directional migration of colonic adenocarcinoma cells.38, 39 We found that functional loss of NOX1 led to reduced phosphorylated p190A and more diffuse focal adhesion complexes in cells migrating at the wound edge along with a reduced density and length of protrusions. This was more prominent in cells at the leading edge and was reflected in our finding of increased speed in a population of cells correlated with the expression of the p22-PHOX component of the NOX1 complex. The concept and importance of leader cells in collective cell migration is well established, with the exposure of leader cells to higher levels of external signals thought to play a major role in extracellular matrix remodeling during migration.31 Given that NOX1 seems to be important in stabilizing focal complexes and production of protrusions, our observations would be consistent with the idea that NOX1 activity is critical primarily in leader cells during wound healing.

In the colon, the primary connection between NOX1 function and mucosal inflammation has remained unclear. The initial finding of patients with early-onset IBD and missense mutations in NOX1 suggested that NOX1 may be a causative factor in mediating colitis.13 However, as discussed by Schwerd et al,14 the high frequency of nonsynonymous mutations in NOX1 suggests that NOX1 is not a highly penetrant Mendelian disorder and that other genetic modifiers or environmental factors may contribute to disease pathogenesis. Similarly, studies in NOX1-deficient mouse models have exhibited a range of effects on mucosal homeostasis. Disruption of NOX1 in mice does not induce spontaneous colitis, but mucosal inflammation can be triggered by combining NOX1 deficiency with the deletion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 or the cellular anti-oxidant proteins GPX1 and GPX2.11 In chemical injury models, loss of NOX1 has led to variable results, with some studies showing delayed recovery and others showing minimal change compared to wild-type mice.12, 30 A number of studies have indicated that NOX1 activity is significantly regulated by intestinal microbiota, and mouse studies of NOX1 deficiency may be significantly confounded by compensatory changes in the microbiome.40 Our genetic analysis did not reveal rare and segregating sequence variants in other known candidate genes for primary immunodeficiency or pediatric IBD, but accumulating human and mouse data suggest that our NOX1 variant likely represents a risk but not a causative factor for colitis. Our studies were not designed to specifically address the question of whether NOX1 deficiency is a monogenic cause of disease in pediatric IBD. However, the studies on the identified stop-gain mutation provide critical insights into the role of human NOX1 in intestinal epithelial restitution and control of epithelial homeostasis and barrier function. In particular, we showed that NOX1 is essential for directing and coordinating epithelial cells during migration and wound healing. Our studies suggest one mechanism by which loss-of-function in intestinal epithelial cell ROS production may impact wound healing and risk for IBD, but potential limitations of the heterologous cellular model system used need to be considered, including the overexpression of the NADPH complex 1 component. Further studies are required to understand how human NOX1-dependent ROS controls cytoskeletal dynamics and directs migration of epithelial leader cells during wound healing and how this determines the progression of intestinal inflammation in vivo. Moreover, studies on larger cohorts of patients are required to define clear genotype-phenotype correlations and additional context-dependent determinants of disease penetrance (eg, genetic factors, environmental factors, microbial changes, immunological dysregulations) in the context of NOX1 deficiency.

In summary, we report that loss of human NOX1 is associated with alterations in epithelial migration dynamics and impaired epithelial wound healing and barrier function.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very thankful to our patients and their parents for allowing us to study their diseases. We thank the medical staff at the Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, University Hospital, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Munich, Germany, and Al-Zahra Hospital, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Author contributions: Razieh Khoshnevisan, Michael Anderson, Stephen Babcock, Sierra Anderson, David Illig, and Benjamin Marquardt performed research on heterologous and patient cells and analyzed data. Katrin Schröder and Franziska Moll conducted RNA scope analysis. Christoph Walz performed histological analysis. Meino Rohlfs conducted whole-exome sequencing, and Sebastian Hollizeck performed the bioinformatics analysis of sequencing data. Roya Sherkat, Peyman Adibi, Abbas Rezaei, Alireza Andalib, Aleixo Muise, Sibylle Koletzko, Christoph Klein, and Scott Snapper recruited and clinically characterized patients and were critical in the interpretation of the human data. Jay Thiagarajah, Christoph Klein and Daniel Kotlarz conceived the study design and supervised Razieh Khoshnevisan, Stephen Babcock, Sierra Anderson, David Illig, and Michael Anderson. Razieh Khoshnevisan, Michael Anderson, Jay Thiagarajah, and Daniel Kotlarz wrote the draft of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supported by: The work was supported by The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the Collaborative Research Consortium SFB1054 project A05 and SFB914 project A08 (DFG), PID-NET (BMBF), and the Care-for-Rare Foundation. Katrin Schröder is supported by the grants SCHR1241/1-1, SFB815/TP1, and SFB834/TPA2 (DFG). Razieh Khoshnevisan received a scholarship from the DAAD Network on Rare Diseases and Personalized Therapies. Daniel Kotlarz has been a scholar with the Reinhard-Frank Stiftung, the International Pediatric Research Foundation, and the Daimler und Benz Stiftung. Jay Thiagarajah is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (K08- DK113106), the American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award, and a Boston Children’s Hospital OFD Career Development Award.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2066–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Circu ML, Aw TY. Intestinal redox biology and oxidative stress. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:729–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van der Vliet A, Janssen-Heininger YMW. Hydrogen peroxide as a damage signal in tissue injury and inflammation: murderer, mediator, or messenger? J Cell Biochem. 2014;115:427–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cordeiro JV, Jacinto A. The role of transcription-independent damage signals in the initiation of epithelial wound healing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:249–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thiagarajah JR, Chang J, Goettel JA, et al. Aquaporin-3 mediates hydrogen peroxide-dependent responses to environmental stress in colonic epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:568–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lambeth JD. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:245–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuhns DB, Alvord WG, Heller T, et al. Residual NADPH oxidase and survival in chronic granulomatous disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2600–2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Muise AM, Xu W, Guo CH, et al. ; NEOPICS NADPH oxidase complex and IBD candidate gene studies: identification of a rare variant in NCF2 that results in reduced binding to RAC2. Gut. 2012;61:1028–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coant N, Ben Mkaddem S, Pedruzzi E, et al. NADPH oxidase 1 modulates WNT and NOTCH1 signaling to control the fate of proliferative progenitor cells in the colon. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2636–2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tréton X, Pedruzzi E, Guichard C, et al. Combined NADPH oxidase 1 and interleukin 10 deficiency induces chronic endoplasmic reticulum stress and causes ulcerative colitis-like disease in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leoni G, Alam A, Neumann PA, et al. Annexin A1, formyl peptide receptor, and NOX1 orchestrate epithelial repair. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:443–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hayes P, Dhillon S, O’Neill K, et al. Defects in NADPH oxidase genes NOX1 and DUOX2 in very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;1:489–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schwerd T, Bryant RV, Pandey S, et al. ; WGS500 Consortium; Oxford IBD cohort study investigators; COLORS in IBD group investigators; UK IBD Genetics Consortium; INTERVAL Study NOX1 loss-of-function genetic variants in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11:562–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kotlarz D, Marquardt B, Barøy T, et al. Human TGF-β1 deficiency causes severe inflammatory bowel disease and encephalopathy. Nat Genet. 2018;50:344–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin). 2012;6:80–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, et al. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vigeland MD, Gjøtterud KS, Selmer KK. FILTUS: a desktop GUI for fast and efficient detection of disease-causing variants, including a novel autozygosity detector. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1592–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. ; Exome Aggregation Consortium Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1073–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adzhubei I, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2013;76:7.20.1–7.20.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vandeweyer G, Van Laer L, Loeys B, et al. VariantDB: a flexible annotation and filtering portal for next generation sequencing data. Genome Med. 2014;6:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Daiber A, Oelze M, August M, et al. Detection of superoxide and peroxynitrite in model systems and mitochondria by the luminol analogue L-012. Free Radic Res. 2004;38:259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang X, McManus M. Lentivirus production. J Vis Exp. 2009;e1499. doi: 10.3791/1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Al Ghouleh I, Rodríguez A, Pagano PJ, et al. Proteomic analysis identifies an NADPH oxidase 1 (NOX1)-mediated role for actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 2 (ARPC2) in promoting smooth muscle cell migration. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:20220–20235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Belousov VV, Fradkov AF, Lukyanov KA, et al. Genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nat Methods. 2006;3:281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vermeire S, Loftus EV Jr, Colombel JF, et al. Long-term efficacy of vedolizumab for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:412–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kato M, Marumo M, Nakayama J, et al. The ROS-generating oxidase NOX1 is required for epithelial restitution following colitis. Exp Anim. 2016;65:197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mayor R, Etienne-Manneville S. The front and rear of collective cell migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stanley A, Thompson K, Hynes A, et al. NADPH oxidase complex-derived reactive oxygen species, the actin cytoskeleton, and Rho GTPases in cell migration. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:2026–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vishwakarma M, Di Russo J, Probst D, et al. Mechanical interactions among followers determine the emergence of leaders in migrating epithelial cell collectives. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Krieglstein CF, Cerwinka WH, Laroux FS, et al. Regulation of murine intestinal inflammation by reactive metabolites of oxygen and nitrogen: divergent roles of superoxide and nitric oxide. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1207–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aviello G, Knaus UG. NADPH oxidases and ROS signaling in the gastrointestinal tract. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11:1011–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ridley AJ. Rho GTPases and actin dynamics in membrane protrusions and vesicle trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:522–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pullikuth AK, Catling AD. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase promotes Rho-dependent focal adhesion formation by suppressing p190A RhoGAP. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:3233–3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sadok A, Bourgarel-Rey V, Gattacceca F, et al. NOX1-dependent superoxide production controls colon adenocarcinoma cell migration. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sadok A, Pierres A, Dahan L, et al. NADPH oxidase 1 controls the persistence of directed cell migration by a Rho-dependent switch of alpha2/alpha3 integrins. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3915–3928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pircalabioru G, Aviello G, Kubica M, et al. Defensive mutualism rescues NADPH oxidase inactivation in gut infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:651–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.