Abstract

We observed that cannabidiol supplements were highly effective in treating an infant boy with drug-resistant early infantile epileptic encephalopathy, eliminating his intractable tonic seizures. The infant began suffering clusters of brief tonic seizures from birth at 39 weeks gestation. EEG showed burst–suppression and seizures could not be controlled by trials of phenobarbital, zonisamide, vitamin B6, clobazam, levetiracetam, topiramate, phenytoin, valproate, high-dose phenobarbital, and ACTH therapy. The boy was discharged from hospital at 130 days of age still averaging tonic seizures 20–30 times per day. We started him on a cannabidiol supplement on day 207, increasing the dosage to 18 mg/kg/d on day 219. His seizures reduced in frequency and completely disappeared by day 234. These effects were maintained, with improved EEG background, even after his other medications were discontinued. Cannabidiol's effectiveness in treating drug-resistant epilepsy has been confirmed in large-scale clinical trials in Europe and the United States; however, no such trials have been run in Asia. In addition, no reports to date have documented its efficacy in an infant as young as six months of age. This important case suggests that high-dose artisanal cannabidiol may effectively treat drug-resistant epilepsy in patients without access to pharmaceutical-grade CBD.

Abbreviations: EIEE, early infantile epileptic encephalopathy; EEG, electroencephalogram; CBD, cannabidiol; THC, tetrahydrocannabidiol; PB, phenobarbital; ZNS, zonisamide; CLB, clobazam; LEV, levetiracetam; PHT, phenytoin; VPA, valproic acid; TPM, topiramate; Br, bromide; LTG, lamotrigine; ACTH, adrenocorticotropin hormone

Keywords: Cannabidiol, Medical marijuana, Epilepsy, Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy

Highlights

-

•

CBD eliminated tonic seizures in a 6-month-old Asian infant with EIEE.

-

•

We believe him to be the youngest epilepsy patient treated with CBD in the literature.

-

•

Not tested in the Epidiolex pivotal trials, CBD may also be effective in Asians.

-

•

High-dose artisanal CBD may be helpful in countries without access to Epidiolex.

1. Background

Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (EIEE), or Ohtahara Syndrome, is a devastating and highly refractory epilepsy syndrome seen with multiple seizure types with onset before 3 months of age [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. Initial electroencephalography (EEG) shows a typical burst–suppression pattern. Many infants with EIEE die within the first 2 years of life, with an average life expectancy of 3 years. In addition to drug-resistant epilepsy, survivors are left with severe neurological deficits and motor impairments as they clinically evolve into West Syndrome (WS) and Lennox–Gastaut Syndrome (LGS).

Epidiolex, a pharmaceutical-grade cannabidiol (CBD) preparation derived from whole plant cannabis, received US Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of Dravet and Lennox–Gastaut Syndromes in 2018 [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6]]. In Japan, however, Epidiolex is unlikely to receive approval due to the presence of measurable traces of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; the main psychoactive component of C. sativa). CBD derived from hemp-stalk, on the other hand, has no trace of THC and is therefore available in Japan. However, there is no experience or guidance on how to use these products in the medical literature. This report details the clinical course of a six-month-old child with EIEE, whose drug-resistant seizures responded to a hemp-stalk-derived CBD supplement.

2. Clinical report

The present case was a six-month-old boy (previously 39 week delivery without complication, birth weight (3192 g, height: 51.0 cm, head circumference: 34.0 cm) noted during his initial exam to exhibit repeated episodes of tonic seizures with cyanosis each lasting 3 min. He was immediately admitted to the NICU following delivery. He had no family history of neuromuscular disease, seizures or dysmorphia, but he was unable to breast feed properly. Exam revealed symmetric pupil size, normal pupillary light reflexes and eye movements. Facial muscles were symmetric, and his arms and legs had normal muscle tone and tendon reflexes. Admission work up revealed WBC: 17,400/μL, CRP: 2.26 mg/L, normal blood amino acid content, lactate/pyruvate ratio, pipecolic acid, and pyridoxal 5′-phosphate levels. Chromosomal analysis revealed normal number and structure. Cranial CT was normal. MRI only showed a left frontal lobe venous malformation. EEG was performed on days 30 and 73 revealing a burst–suppression pattern during awake and sleep (Fig. 1a). The boy's parents did not approve detailed genetic or metabolic testing following the MRI, but based on his clinical course, symptoms, and EEG, we diagnosed the boy with EIEE.

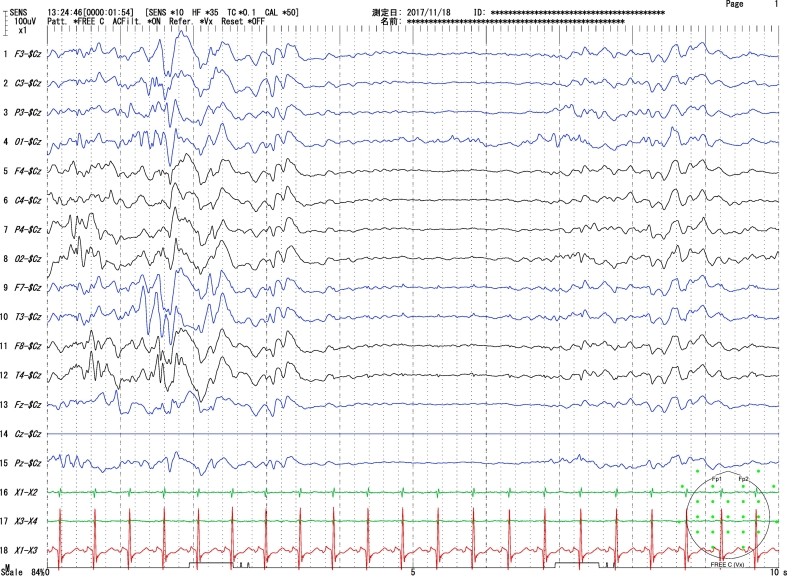

Fig. 1a.

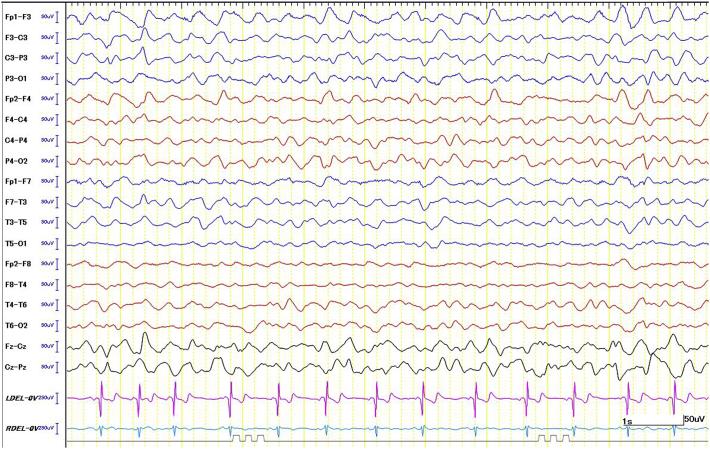

Sleep EEG (day 30): Burst–suppression pattern with 3–4 s of suppression between bursts of high amplitude slow wave with multi-focal spikes.

2.1. Anti-seizure drug treatment course

Intravenous phenobarbital (PB) was initiated on Day 0. Zonisamide (ZNS) was added to his drug regimen on Day 4, and vitamin B6 on Day 8, yet he continued to suffer frequent tonic seizures. Tapering off PB, discontinuing vitamin B6, and gradually increasing ZNS were also ineffective. Next, clobazam (CLB), levetiracetam (LEV), and phenytoin (PHT) were added in sequence to the regimen, taken in combination with ZNS. However, each antiseizure drug was discontinued after failing to control seizures (Fig. 2a). He restarted high dose PB on Day 39 and tapered off ZNS while sodium valproate (VPA) and topiramate (TPM) were introduced. Sadly, these also failed to achieve effective seizure control. On Day 84, while on PB + TPM, the boy began to exhibit infantile spasms and EEG began to transition into hypsarrhythmia (Fig. 1b shows EEG correlate of spasm only). The spasms showed signs of abatement after starting ACTH therapy (0.025 mg/kg/alternate-days × 9 courses), but not the tonic seizures. Lamotrigine (LTG) was added to his PB regimen on Day 118, and sodium bromide (Br) on Day 120. The boy was discharged home the same day (Fig. 2b).

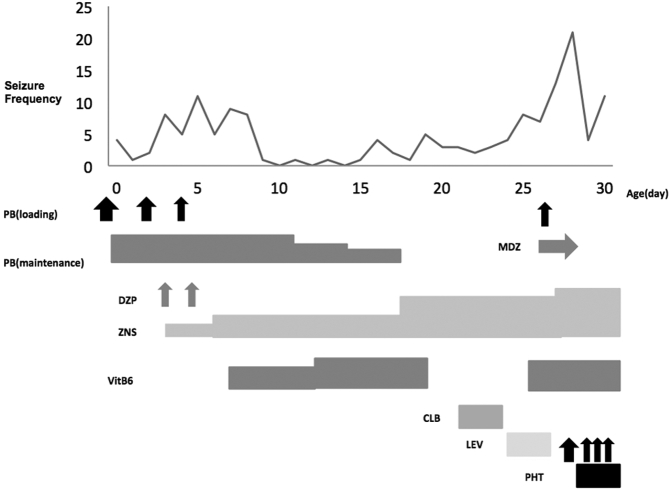

Fig. 2a.

Seizure chart (Day 0–30).

Vertical axis: number of generalized seizures per day. Horizontal axis: Age (day).

PB: phenobarbital, MDZ: midazolam, DZP: diazepam, ZNS: zonisamide, VitB6: vitamin B6, CLB: clobazam, LEV: levetiracetam, PHT: phenytoin.

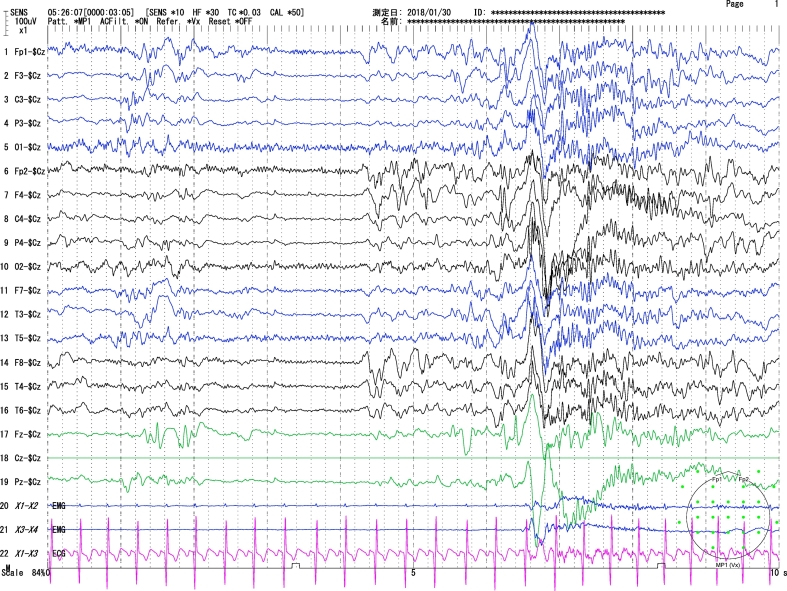

Fig. 1b.

EEG during an attack (day 30): brief generalized spikes were recorded. Epileptic spasms were recorded on video synchronous with the high amplitude slow waves with overriding fast activity.

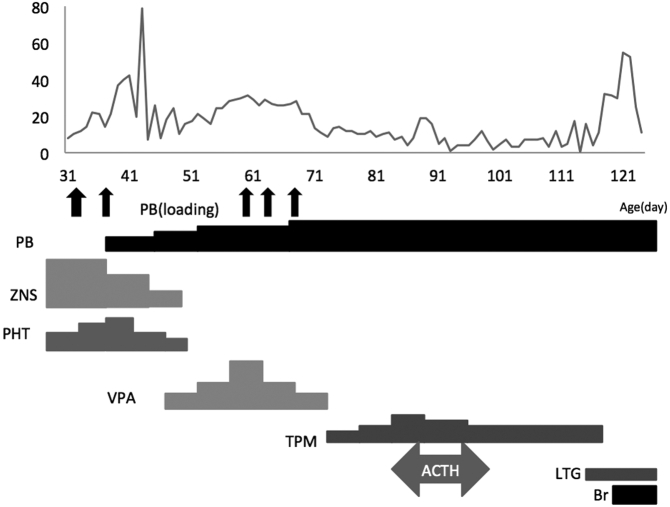

Fig. 2b.

Seizure chart (Day 30–120).

Vertical axis: number of generalized seizures per day. Horizontal axis: Age (day).

PB: phenobarbital, ZNS: zonisamide, PHT: phenytoin, VPA: sodium valproate, TPM: topiramate, ACTH: adrenocorticotropic hormone, LTG: lamotrigine, Br: potassium bromide.

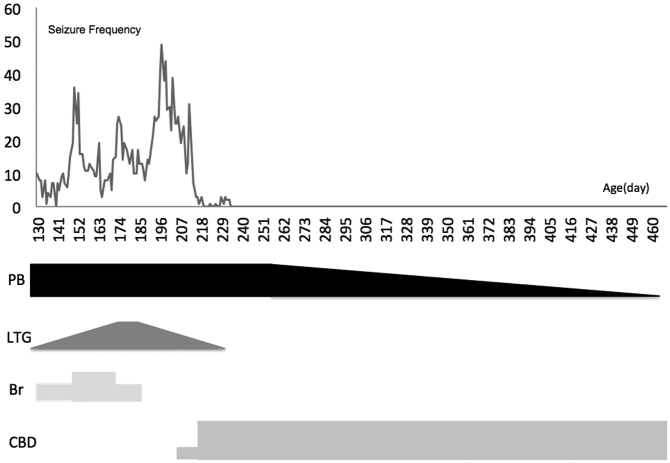

He continued to have seizures at home and was taken off Br on Day 186. At his parents' request, an oral CBD paste supplement was added to his regimen on day 207 (HempMeds® 380 mg/1000 mg), at a dosage of 6 mg/kg/d divided twice daily begun without titration. The parents sought epilepsy consultation (Y.M.) on day 211, who advised them to modify the treatment to reflect typical Epidolex® Greenwich Biosciences, Inc., Carlsbad, CA dosing and switched compounds to a CBD tincture on day 219 (Hemptouch® 1500 mg/10 mL). This medication was switched without titration to an increased oral dosage of 18 mg/kg/d divided twice daily, based on Epidolex recommended target dosing between 10 and 20 mg/kg/d. Thereafter, his tonic seizures reduced in frequency, and were completely eliminated by day 234 (Fig. 3). He was gradually tapered off LTG and then PB, switching completely to CBD monotherapy on day 493. The boy's parents have observed no clear recurrence of tonic seizures to date, nearly 11 months after he began taking CBD (Fig. 4). Background EEG patterns in a recording made on day 326 showed clear improvements over the previous time (Fig. 5). No significant side effects were reported.

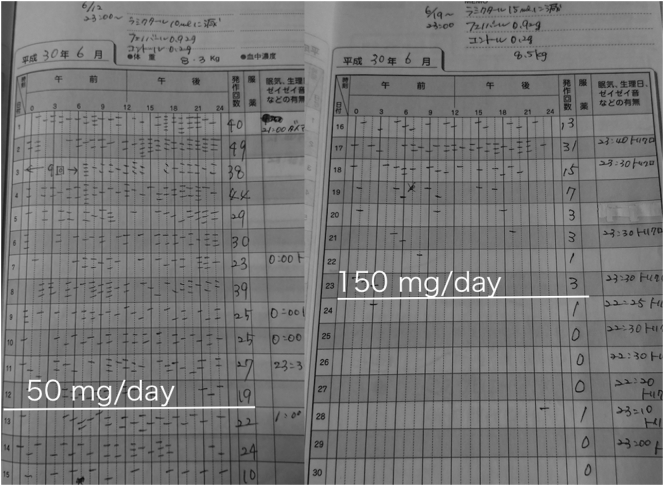

Fig. 3.

Seizure event diary around CBD initiation.

The patient started taking CBD paste (50 mg/day) noted at first white line and increased to CBD tincture (150 mg/day) noted at second white line. Hash marks are individual tonic seizures observed by parents. Daily count summarized in the column to the far right of the day number.

Fig. 4.

Seizure chart after discharge (Day 121–460).

Vertical axis: number of generalized seizures per day. Horizontal axis: Age (day).

PB: phenobarbital, LTG: lamotrigine, Br: potassium bromide, CBD: cannabidiol.

Fig. 5.

Sleeping EEG (Day 326). Background rhythms improved compared with Fig. 1a, Fig. 1b.

At last exam, the child has severe developmental delays, poor head control, and requires full assistance to manage oral nutrition.

3. Discussion/conclusion

The natural history of EIEE does not usually exhibit seizure remission so abruptly or so early in its course. We feel this experience is significant to report for several reasons.

There is convincing evidence that this child's remission was due to the high-dose CBD introduced on day 219, because prior to this transition, he had received multiple antiseizure medications as a standard of care without any clear effect. In the 12 days preceding addition of the CBD paste, the boy averaged 32 tonic seizures per day (see Fig. 3). In the 11 days prior to transition to high dose CBD tincture, his tonic seizure count had already improved to 12 per day. And in the 7 days after high dose CBD had started, he only logged 2 tonic seizures. While observer bias is certainly a concern in this case, the tapering of his concomitant antiepileptic drugs, with preserved tonic seizure remission, remains compelling.

Furthermore, this report is novel because we believe it is the only report in the medical literature of CBD used for this diagnosis and in a child of this age. In addition, for countries such as Japan in which Epidiolex is prohibited because of its THC content, this report may offer guidance to other physicians and providers caring for drug-resistant epilepsy patients.

Ethical statement

We have reviewed the “ethical duties of the author” regarding reporting, originality, confidentiality, authorship, declaration of competing interests, and clinical transparency, and affirm that we are in compliance with these requirements.

Consent was obtained from the boy's parents to describe their child's clinical course and test findings before preparing this case report.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors YM, IT, HY have no conflict of interest. EM is a member of Greenwich Pharmaceutical Speakers Bureau Program. This report is not a funded research.

Contributor Information

Yuji Masataka, Email: yuji.masataka@gmail.com, https://www.greenzonejapan.com.

Ichiro Takumi, Email: takumi@marianna-u.ac.jp.

Edward Maa, Email: Edward.maa@dhha.org.

Hitoshi Yamamoto, Email: h3yama@marianna-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.EPIDIOLEX (cannabidiol) oral solution [Internet]. Washington DC:FDA [cited 2019 Feb 15] Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/210365lbl.pdf

- 2.Devinsky O., Cross J.H., Laux L., Marsh E., Miller I., Nabbout R. Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the Dravet syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2011–2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devinsky O., Patel A.D., Cross J.H., Villaneuva V., Wirrell E.C., Privitera M. Effect of cannabidiol on drop seizures in the Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1888–1897. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laux L.C., Bebin E.M., Checketts D., Chez M., Flamini R., Marsh E.D. Long-term safety and efficacy of cannabidiol in children and adults with treatment resistant Lennox–Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome: expanded access program results. Epilepsy Res. 2019;154:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2019.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devinsky O., Cilio M.R., Cross H., Fernandez-Ruiz J., French J., Hill C. Cannabidiol: pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia. 2014;55:791–802. doi: 10.1111/epi.12631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaston T.E., Friedman D. Pharmacology of cannabinoids in the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;70:313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohtahara S., Yamatogi Y. Ohtahara syndrome: with special reference to its developmental aspects for differentiating from early myoclonic encephalopathy. Epilepsy Res. 2006;70(Suppl. 1):S58–S67. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]