Abstract

The principal objective of this research was to demonstrate the sensitivity and selectivity of carbon paste electrode modified with Ocimum Sanctum leaf extract synthesized silver nanoparticles for simultaneous determination of Cd(II) and Pb(II) in discharged textile effluent. While UV-Vis, XRD and FT-IR were used to fully characterize the green synthesized silver nanoparticles, cyclic voltammetry was used to evaluate the electrochemical behavior of the two metals at the modified electrode relative to the unmodified electrode. Square wave anodic stripping (SWAS) voltammetric current showed linear dependence on the concentration in the range 5–160 ppm with determination coefficients (R2) of 0.9976 and 0.9996 for Cd(II) and Pb(II), respectively. The method also showed extremely low detection limit (0.0891ppm for Cd(II) and 0.048 ppm for Pb(II)) making the method superior over the previously reported methods. Recovery results of 94.3 for Cd(II) and 101.0% for Pb(II) validated the applicability of the method for simultaneous determination of the two metals in a complex matrix textile effluent sample. While levels of Pb(II) and Cd(II) in the untreated sample were 117.0 and 128.3 ppm, their levels in the treated sample were 17.7 and 101.4 ppm, respectively confirming the low efficiency of the treatment plant the factory claims to have. The level of the studied metals in the discharged effluent is much higher than the permissible limit indicating extent of pollution of the water system to which the effluent is discharged.

Keywords: Environmental science, Analytical chemistry, Nanotechnology, Green synthesis, Modified carbon paste electrode, Ocimum sanctum leaf extract, Silver nanoparticles

Environmental science, Inorganic chemistry, Nanotechnology, Green synthesis; Modified carbon paste electrode; Ocimum sanctum leaf extract; Silver nanoparticles.

1. Introduction

Heavy metals in general are metallic elements that possess specific density higher than 5 g/cm3. Heavy metals which are known for their adverse effects to the ecosystem and living organisms although to different extents [1] are of two categories. Many of the heavy metals including cobalt, chromium, copper, iron, manganese, nickel and zinc are essential metals that are required for various physiological and biochemical functions in the body. While inadequate intake of this group of heavy metals lead to deficiency diseases or syndromes, their consumption beyond the respective threshold level or chronic exposure may also cause acute or chronic toxicities [2]. The other category of heavy metals that are totally toxic includes lead, cadmium, mercury, and Arsenic.

Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in living organisms and human body may cause adverse effects including slowing the progression of physical, muscular and neurological, degenerative processes that mimic certain diseases such as Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease [3]. Heavy metals may even damage nucleic acids, causing mutation, mimic hormones thereby disrupting the endocrine and reproductive system and eventually lead to cancer [4].

Humans may experience occupational or environmental exposure to heavy metals in contaminated air, soil, water, or foodstuffs usually via inhalation, dermal, or ingestion routes [4]. Potential sources to heavy metals exposure include natural sources (like groundwater, metal ores), industrial processes, commercial products, folk remedies, and contaminated food and herbal products [5].

The treated and untreated discharged effluents from industries are reported to contain heavy metals including Pb(II) and Cd(II) [6] mainly as ingredients of paints and dyes which induce their toxic effect on the food chain even at a distance from the point of discharging. The river to which contaminated industrial effluents are discharged may be used for irrigation there by polluting the soil on which vegetables are grown. Depending on the transfer coefficient of each heavy metal from the soil to the cultivated vegetable, metals will have the chance to enter in the animal metabolic system, accumulated leading to its toxic effect.

Most importantly the central nervous system, kidneys and blood are extremely vulnerable, culminating in death at excessive levels of lead. Case-control studies on mental retardation and hyperactivity in relation to environmental lead exposure showed that children who survived acute lead intoxication were often left with severe deficits in neurobehavioral function [7].

Acute and chronic exposure to cadmium gives rise to health complications for both human beings and animals. According to EPA cancer guideline as cited in Dokmeci et al. (2009) [8], cadmium which can enter our body by smoking, inhaling air, and through food or drink, has been categorized as potential carcinogen. Renal damage, osteoporosis and possibly renal cancer are health complications arising from oral exposure to cadmium. Chronic exposure even to very low amount of cadmium results in adverse renal and negative bone effects leading to the so called Itai-itai disease. Cadmium (II) and lead (II) are the most common toxic heavy metals that are being eluted from textile factories. Textile industries as the major sources of pollution and contributors of metal contaminants including Pb(II) and Cd(II) [9] used to discharge their metal containing effluents in to fresh water without any adequate treatment necessitating continuous monitoring of the heavy metal dose in the discharges before causing health problems.

Analytical techniques including AAS [10], ICP-OES [11] and ICP-AES [12] have been reported for simultaneous determination of Pb(II) and Cd(II) in industrial effluents. However, these techniques in general are not specific to a particular oxidation state of the species under consideration, entail high cost of analysis, their instrumentation is intricate and they call for long analysis time [13]. On the contrary, electrochemical methods are specific to a particular oxidation state of a species, their cost of analysis per unit sample is relatively cheap vis-à-vis spectroscopic technique, and their detection limit is low vis-à-vis other advanced analytical techniques [14].

Attempts have been made on the electrochemical determination of Pb(II) and Cd(II) in industrial discharged effluents [15]. However, to the best of our knowledge silver nanoparticles modified carbon paste electrode has not been reported for simultaneous determination of Pb(II) and Cd(II) in discharged effluent of a textile factory. Thus, this paper elaborates green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ocimum Sanctum leaf extract and application of the silver nanoparticle modified carbon paste electrode (AgNs/CPE) for square wave anodic striping voltammetric (SWASV) simultaneous determination of Pb(II) and Cd(II) in untreated and treated textile effluent samples.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

All chemicals used in this work were of analytical grade. Silver nitrate (BDH), graphite powder (≥99.0%, Blulux), paraffin oil (BDH), Cd(NO3).4H2O. (99.5%, BDH), Pb(NO3)2 (99.5%, BDH), HNO3 (65%, UNI-CHEM), HCl (37%, Blulux), H2O2 (30%, Blulux), glacial acetic acid (99.5%, Blulux), sodium acetate (98%, Blulux), sodium hydroxide (97%, Blulux), and distilled water were used.

CHI760 electrochemical workstation (Austin, Texas, USA), Nimbus analytical electronic balance (USA), heating mantle (Hoven Labs, Korea), magnetic stirrer, centrifuge (Remuigyog bomba, India), mortar and pestle, pH meter (Adwa, Hungary), UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Beijing), X-ray diffractometer (MiniFlex 610, USA), FT-IR spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Germany), and hot plate (Daihan scientific, Korea).

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Extracting Ocimum sanctum (holy basil) leaf

Ocimum sanctum (holy basil) leaf was extracted following a reported procedure [16]. Briefly: Ocimum sanctum leaf collected from around Bahir Dar city was washed with distilled water four times thoroughly to obviate dust particles. 20 g of the chopped leaf was transferred in to 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask to which 100 mL of distilled water was added. The mixture was boiled at 100 °C for 5 min using heating mantle. The conical flask was then removed from the heating mantle and allowed to cool to room temperature. The extract, filtered using Whatman no one filter paper, was then collected and kept in a refrigerator for further experiments.

2.2.2. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ocimum sanctum leaf extract

30 mL of 10 mM aqueous solution of AgNO3 and 3 mL of the crude leaf extract were blended, stirring magnetically for about 10 min and then left until a dark brown color appears confirming formation of the nanoparticles. The silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) colloidal suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min and the nanomaterial was separated by decantation. The collected nanoparticle was further dried using heating mantle. In order to avoid error that results from high optical density of the solution, 0.5 mL of a 10 times diluted with distilled water AgNPs suspension was used for UV-Vis analysis [16]. After the reaction mixture was allowed to stand for 45 min, a dark brown color was observed.

2.2.3. Preparation of carbon paste electrode

Unmodified carbon paste electrode was prepared following a procedure reported elsewhere [ [17]. Briefly: 1.0 g of graphite powder and 0.429 g of paraffin oil (in a ratio of 70:30%w/w) were mixed and homogenized thoroughly with a mortar and pestle for 40 min. The paste was then left for further 24 h. Finally, the carbon paste was crammed in to a Teflon tube on the opposite side of which a copper wire was inserted to establish electrical contact. The surface of the prepared carbon paste electrode was smoothed on a clean paper before use.

Keeping the amount of the graphite powder and paraffin oil constant (1.0 and 0.429 g, respectively), four modified carbon paste electrodes were prepared varying the mass of AgNPs added (15, 20, 30, and 40 mg of AgNPs). The four mixtures of graphite powder, paraffin, and varied amounts of AgNPs were homogenized for 40 min and left for further 24 h. Finally, four carbon paste electrodes modified with various amounts of the AgNPs were prepared.

2.2.4. Electrochemical measurements

Voltammetric experiments were carried out using CHI760D Electrochemical Workstation (Austin, Texas, USA) connected to a personal computer. All electrochemical experiments were performed employing a conventional three-electrode system with a CPE or CPE/AgNPs as the working electrode, platinum coil as an auxiliary electrode, and Ag/AgCl as a reference electrode. All experiments were conducted 24 ± 2 °C.

2.2.5. Solution preparation

0.1 M acetate buffer solution (ABS) was prepared by mixing the appropriate volumes of equi-molar (0.1 M) CH3COONa and CH3COOH solutions in deionized water and adjusted to the required pH using 0.1 M HCl and NaOH solutions.

100 mL of 1000 ppm stock solutions of cadmium(II) and lead(II) were prepared separately by dissolving the appropriate masses of Cd(NO3)2.4H2O, and Pb(NO3)2 in pH 4.5 ABS, respectively. A 100 mL of 100 ppm working solution in pH 4.5 ABS for each metal was prepared from the stock solution by dilution. Moreover, three sets of calibration standard solutions of the analyzed metals (Pb & Cd); both parallelly varying concentration (5–160 ppm), Cd(II) varying between 5–160 ppm while Pb(II) is kept to 20 ppm, and Pb(II) varying between 5–160 while Cd(II) is kept to 20 ppm were prepared from the stock and intermediate solutions using the optimized pH 6 ABS.

2.3. Collection and digestion of industrial effluent

2.3.1. Collection of industrial effluent

Time weighted (Morning, Noon, and Afternoon) effluent samples (before treatment and after treatment) were collected from Bahir Dar Textile Factory with 500 mL polyethylene plastic bottles rinsed thoroughly with dilute HNO3. A 500 mL representative composite sample for each site (before and after treatment) was obtained by mixing the time dependent collected discharges in an equal volume.

2.3.2. Sample digestion

Each 100 mL of sample (influent and effluent) was taken in to 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask to which a mixture of 30 mL of 65% HNO3, 15 mL of 37% HCl and 1.24 mL of 30% H2O2 was added [18]. The sample was then digested for 1 h using hot plate at 95 °C until brown gas was completely removed. The flask was removed from the hot plate following formation of a limpid solution and let to cool to room temperature. The solution was then transferred in to a100 mL volumetric flask by filtering with Whatman no 1 filter paper which was then diluted to the mark with distilled water. The resulting solutions of the influent and effluent samples were kept meticulously in refrigerator until they were analyzed.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of AgNPs

Four techniques (Ultraviolet visible spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and cyclic voltammetry) were applied to characterize the AgNPs synthesized following the green procedure described under the experimental section.

3.1.1. UV-visible spectroscopic characterization

To attest whether the synthesized nanoparticles are silver nanoparticles or not, UV- Visible spectroscopy was employed. Figure 1 presents the UV-Vis spectra in the range of 300–700 nm for the AgNO3 solution, crude leaf extract, and the dark brown colored mixture of the two. While no peaks were observed for both the precursor solution (curve a) and crude leaf extract (curve b) at the expected wave length range of silver nanoparticles, a well-shaped peak centered at about λmax 407 nm (curve c) for the mixture of the precursor solution and plant extract confirmed synthesis of small size silver nanoparticles [19]. This absorption peak appeared at the characteristic wave length of 407 nm could be ascribed to the so called surface Plasmon resonance of silver which is due to resonance of valence electrons of atomic silver between the conduction and valence bands.

Figure 1.

UV- Visible spectrum of (a) AgNO3 aqueous solution, (b) crude extract of holy basil leaf, and (c) mixture (a and b).

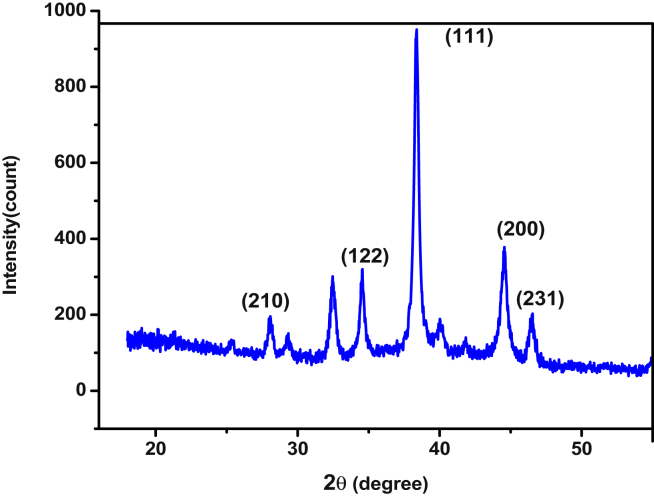

3.1.2. X-ray diffraction analysis

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted to evaluate the crystalline nature, distance between parallel planes (dhkl), and particle size of the synthesized AgNPs. Figure 2 presents the XRD pattern for the synthesized AgNPs recorded in the 2θ range of 20–550 and characteristic wave length of 0.15406. The peaks that appeared at 2θ values of 38.4 and 44.5 with Miller indices of (111) and (200), respectively represent the characteristic peaks for crystalline silver nanoparticles [19]. The spacing between the parallel planes of the synthesized FCC crystalline structure of the silver nanoparticle (dhkl) calculated using the Bragg's equation (eqn. (1)) was found to be in the range 0.205–0.234 nm.

| (1) |

Figure 2.

XRD Pattern of the synthesized AgNPs using Ocimum sanctum leaf extract.

Furthermore, the average particle size of the synthesized AgNPs as calculated using the Debye-Scherrer equation (eqn. (2)) [20], was found to be 23.17 nm which is in agreement with its literature value [21] confirmed synthesis of the AgNPs with a reasonable size.

| (2) |

where ‘W’ is FWHM (full width in radians at half maximum), 'θ' is the diffraction angle and 'D' is particle diameter (size).

3.1.3. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis

FT-IR experimental result (Figure 3A) revealed very intense and broad band at a frequency of 3468 cm−1 attesting the –O–H stretching due to –OH functional group in the Ocimum sanctum leaf extract. This might be attributed to the –OH functional group in the globulol alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, terpenoids, and others reported to be present in Ocimum sanctum leaf extract which are responsible for reducing silver cation to metallic silver [22]. The weak absorption band at a frequency of 2076 cm−1 is owing to the presence of bio-molecules containing –C–C– triple bond. Appearance of sharp and medium band at a frequency of 1654 cm−1could be due to the presence of organic compounds containing carbonyl group. In contrast to the bands in Figure 3A, a strong and sharp peak at 3445 cm−1 (Figure 3B) which is still due to –O–H stretching signifies the presence of eugenol and phenol in the silver nanoparticles. The observed decrease in the broadness of the peak centered at 3445 cm−1 may be an indication of the decrease in the –OH functional groups due to their oxidation leading to formation of AgNPs. The doublet weak spike-like peaks at 2911cm−1 and 2839 cm−1 were assigned for aldehydic –C–H stretching which authenticates the presence of aldehyde functional group in the synthesized AgNPs. As it has been clarified in reported materials, the organic compounds that are responsible for reducing Ag (I) in to metallic silver Ag0 contain aldehyde. Appearance of a medium and sharp peak at 1637 cm−1 ascertains the presence of alkene. Furthermore, while the strong and sharp peak at 1401 cm−1 corroborates the presence of alkanes, a weak and sharp peak at 1042 cm−1 indicated –C−O− stretching. Generally, appearance of new peaks or peaks with different features in the mixture of the plant extract and precursor added with the observed color change could be taken as confirmation of formation of new substance, the AgNPs.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of A) holy basil leaf extract B) AgNPs.

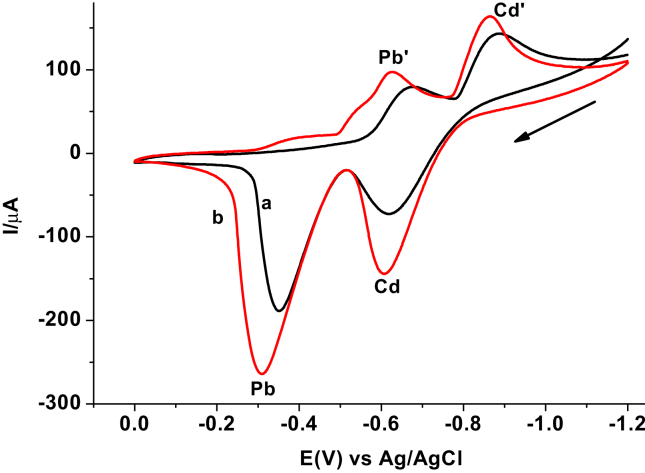

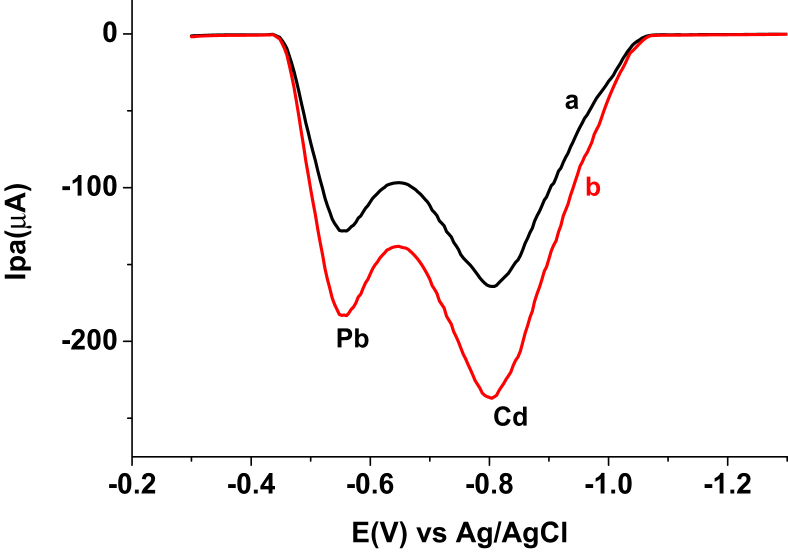

3.1.4. Electrochemical characterization of Pb2+ and Cd2+ at the CPEs

To evaluate the sensitivity and selectivity of the AgNPs modified CPE over the unmodified CPE towards the electrochemical reaction of both the analytes, cyclic voltammograms of 100 ppm mix of Cd(II) and Pb(II) in pH 4.5 ABS (Figure 4) were recorded. As it can be seen from the figure, the redox couple peak current response in general and anodic peak current in particular of the CPE modified with silver nanoparticles (CPE/AgNPs) for both metal ions (curve b) is higher than the unmodified for the same (curve a). The observed significant peak current enhancement, decrease in over potential, and slight decrease in peak potential difference (ca. 20 mV) at the CPE/AgNPs indicated the electrocatalytic property of the modifier which may be accounted for increased conductivity and surface area of the AgNPs [13]. Thus, AgNPs/CPE was selected for simultaneous determination of the level of lead and cadmium in the discharged effluents of Bahir Dar Textile Factory.

Figure 4.

Cyclic voltammograms of a mixture of 100 ppm Pb(II) and Cd(II) in pH 4.5 ABS at a) unmodified and b) modified CPE.

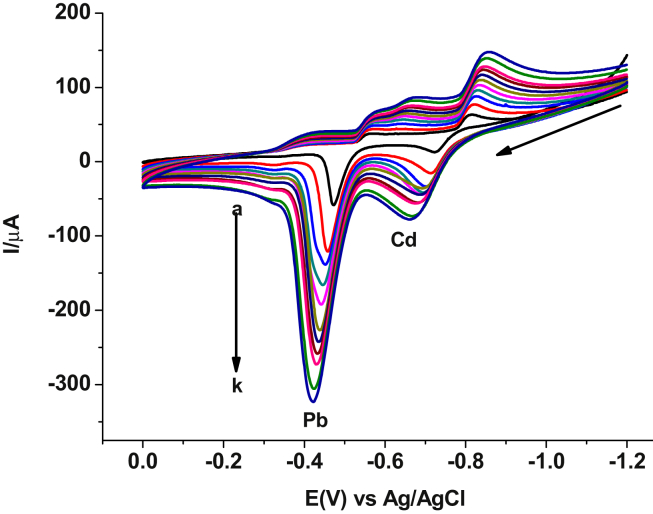

3.1.5. Effect of scan rate on the peak potential and peak current

In order to investigate the reversibility of the redox reaction each metal undergoes at the modified carbon paste electrode, effect of the scan rate on the respective peak potential values was examined. As can be seen from Figure 5, both oxidation and reduction peaks for each metal showed potential shift with scan rate confirming the irreversibility of the redox couples.

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltammograms of AgNs/CPE in pH 4.5 ABS containing a mixture of 100 ppm Pb(II) and Cd(II) at various scan rates (a–k: 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 125, 150, 175, 200, 250, and 300 mV s-1, respectively).

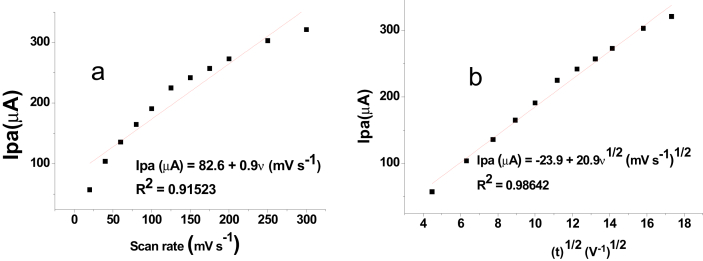

Moreover, the kinetics of the redox process was investigated by comparing the correlation coefficient values (R2) for the dependence of peak current on the scan rate and square root of scan rate. The observed higher correlation of the peak current with square root of scan rate (R2 = 0.98642) than the correlation of the peak current on scan rate (R2 = 0.91523) (Figure 6) revealed that the oxidation reaction of both metals at the CPE/AgNPs electrode was controlled by mass transfer although charge transfer also contributed significantly.

Figure 6.

Plot of anodic peak current of lead as a function of (a) scan rate and (b) square root of scan rate.

3.2. SWASV for simultaneous determination of Pb(II) and Cd(II)

As square wave is more sensitive and more powerful to discriminate the Faradaic from the non-Faradaic current than cyclic voltammetry, square wave anodic stripping voltammetry (SWASV) was used for simultaneous determination of Pb(II) and Cd(II) in discharged tannery effluent samples from Bahir Dar Textile factory, Bahr Dar, Ethiopia. Using the SWASV method, the silver nanoparticles loading, pH of the supporting electrolyte, and deposition parameters (potential Eacc & time tacc) were optimized with the default method parameters.

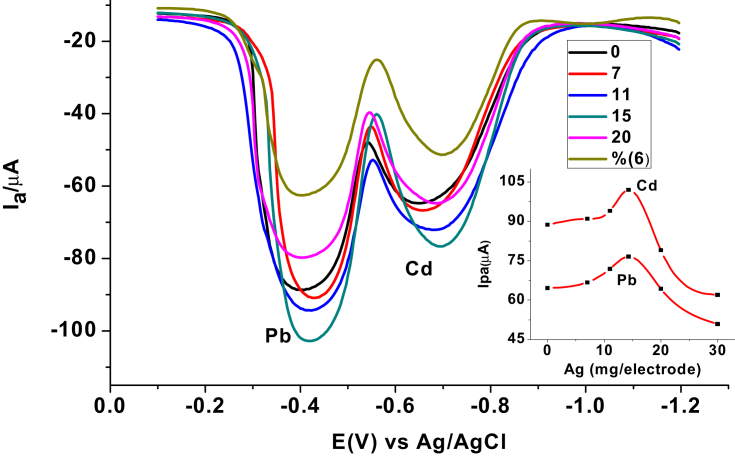

3.2.1. Optimization of silver loading

The silver nanoparticle loading effect on the peak current response of the CPE/AgNPs for both the studied metals was checked. Six carbon paste electrodes with various proportion of AgNPs modifier (0, 7, 11, 15, 20, and 30 mg) were prepared. Figure 7 presents the square wave voltammograms of mixture of 100 ppm Cd(II) and Pb(II) at carbon paste electrodes loaded with various amounts of AgNPs. As can be seen from the figure, the electrode modified with 15 mg of AgNPs revealed the most intensive anodic peaks for both the analytes. Thus, carbon paste electrode prepared by mixing 1 g of graphite powder, 0.429 g of paraffin oil, and 15 mg of AgNPs was used for further experiments.

Figure 7.

SWASVs of 100 ppm mixture of Cd(II), and Pb(II) in pH 4.5 ABS at CPE modified with AgNPs of various amounts (0, 7, 11, 15, 20, 30 mg of Ag per electrode). Insert: Ipa of the studied metals versus the amount of silver nanoparticles used per electrode.

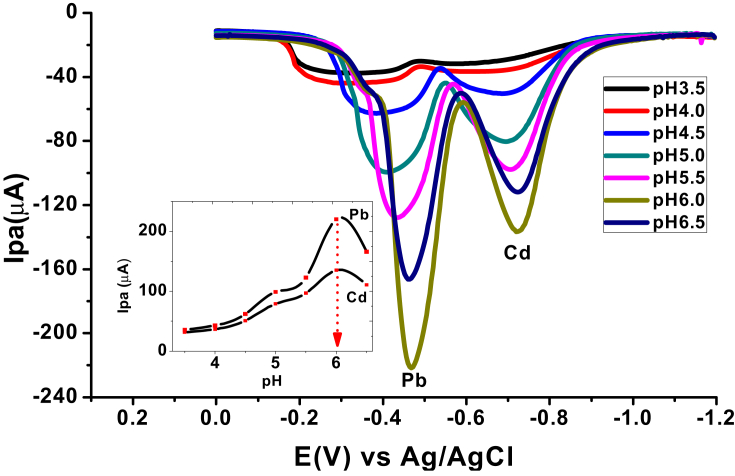

3.2.2. Effect of solution pH on peak current and peak potential

The effect of pH on the anodic stripping voltammetric response of the AgNPs/CPE towards Cd(II) and Pb(II) in the pH range of 3.5–6.5 was surveyed (Figure 8). As it can be seen from the figure (Inset), the anodic peak current increased with pH from 3.5 to 6.0 and then declined at pHs beyond 6.0 showing that pH 6.0 is the optimum solution pH for the analysis.

Figure 8.

Square wave anodic stripping voltammograms (ASSWV) of a mixture of 100 ppm Cd (II) and 100 ppm Pb (II) in ABS of various pHs (3.5, 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5, 6.0, and 6.5) at Eacc = -1.1 V, and tacc = 10 s. Inset: plot of peak current versus pH.

So as to examine the reaction mechanism of the electrochemical reaction, the dependence of anodic peak potential on pH was investigated (Figure 9), As depicted in the figure, observed peak potential shift with pH for both metals with a slope of 73.65 for Cd (II) and 43.43 for Pb (II) indicated participation of electrons and protons in a ratio of 1:1 in the rate determining step. The number of electrons participated was estimated using eqn. (3) for an irreversible, adsorption reaction [23, 24].

| (3) |

Where Epa is the anodic peak potential, Epa/2 (half-wave potential) is the potential at half height of the peak, α-is the electron transfer coefficient (0.3 < α < 0.7) for an irreversible reaction, and n-is the number of electrons involved.

Figure 9.

Linear dependence of Epa on pH for (a) Cd (II) and (b) Pb (II).

Taking the α-value for an irreversible reaction be 0.5 and the Epa-Epa/2 values for Pb(II) and Cd(II) in this work to be 79 and 75 mV, respectively; number electrons involved in each reaction was estimated to be n ≈ 2.

3.2.3. Optimization of deposition parameters

3.2.3.1. Deposition potential (Eacc)

As the method which was selected for determination of the two metals in the effluent sample is stripping, the deposition potential that gives the maximum anodic current response was optimized by varying the potential from −1.3 to −0.9 V keeping the deposition time at 10 s (Figure 10). As it is observed from the figure (Inset), the anodic peak current for both analytes increased from Eacc of −1.3 to −1.1 V and then decreased at deposition potentials beyond −1.1 V. Thus, Eacc of −1.1 V was chosen for further analysis.

Figure 10.

SWASVs of mixture of 100 ppm Pb(II) and 100 ppm Cd(II) at various Eacc (-1.3, -1.2, -1.1, -1.0, and -0.9 V) in ABS of pH 6 tacc of 10 s. Inset: plot of Ipa (Pb(II) vs Eacc.

3.2.3.2. Accumulation time (tacc)

The optimum accumulation time was determined fixing accumulation potential at −1.1 V Figure 11 presents SWASVs of mixture of the metal ions in pH 6.0 ABS at Eacc of −1.1 V and various deposition times from (0–60 s). As can be seen from the inset of the figure, the anodic peak current response of the AgNPs/CPE for the 100 ppm mixture of the analytes increased from 0 to 40 s and then leveled off beyond 40 s making 40 s as the optimum deposition time.

Figure 11.

SWASVs of AgNs/CPE in pH 6.0 ABS containing a mixture of 100 ppm Cd (II) and Pb(II) in pH 6 ABS.at Eacc -1.1 V and various tacc (0–60 s). Inset: plot of Ipa of Pb(II) versus tacc. Eacc an = -1.1 V.

3.2.4. Dependence of peak current on concentration of Cd(II) and Pb(II)

The dependence of the SWASV peak current on the concentrations of the two analytes was evaluated under three different conditions; concentration of both is varying parallelly, concentration of Cd(II) is varying keeping Pb(II) constant, and Pb(II) is varying keeping Cd(II) constant in order to see the effect of the presence one on the determination of the other.

3.2.4.1. Both variable concentration calibration

As it can be seen from the inset of Figure 12, the anodic peak current of both analytes showed linear dependence on the concentration in the studied concentration range although with different sensitivity and correlation coefficients. This indicated the possibility of simultaneous determination of the two metals in a sample [25].

Figure 12.

SWASVs AgNs/CPE in pH 6.0 ABS containing different equi-molar mixture of Pb(II) and Cd(II) (a–f: 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 ppm, respectively) at Eacc -1.1 V and tacc 40 s.

3.2.4.2. Calibration curve of Cd(II) at constant concentration of Pb(II)

To evaluate effect of the presence of Pb(II) on the determination of Cd(II), dependence of anodic peak current response of the modified electrode on the concentration of Cd(II) in the presence of fixed concentration of Pb(II) was recoded (Figure 13). Surprisingly, the anodic peak current of Cd(II) increased linearly with concentration (R2 = 0.9976) whereas the anodic peak current for the constant concentration of Pb(II) remaining constant. This confirmed the possibility of determining Cd(II) even in the presence of Pb(II).

Figure 13.

SWASVs of AgNs/CPE in pH 6.0 ABS containing 20 ppm of Pb(II) and variable concentrations of Cd(II) (a–f: 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 ppm, respectively) at Eacc -1.1 V and tacc 40 s.

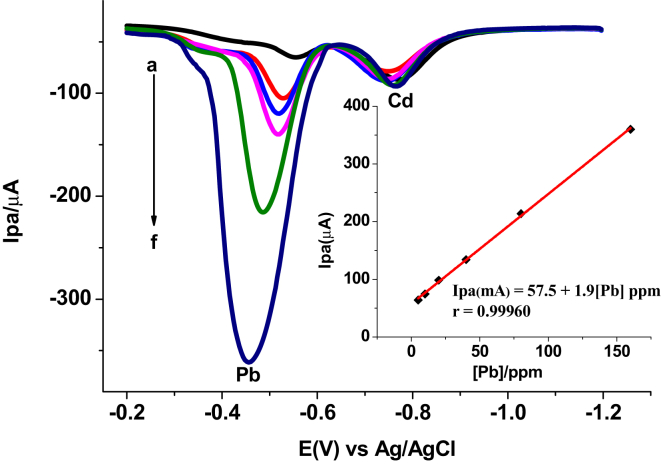

3.2.4.3. Calibration curve of Pb(II) at constant concentration of Cd(II)

The influence of the presence of constant amount of Cd(II) on the linear dependence of the anodic peak current of Pb(II) on its concentration was further evaluated. Figure 14 presents the SWASVs of various concentrations of Pb(II) while the concentration of Cd(II) was kept constant under the optimized solution and method parameters. The anodic peak current for Pb(II) showed linear dependence on the studied range of concentration with a correlation coefficient of 0.9996. This also confirmed the possibility for the simultaneous determination of the two metals in a sample like the effluent of a textile factory.

Figure 14.

SWASVs AgNs/CPE in pH 6.0 ABS containing 20 ppm of Cd(II) and various concentrations of Pb(II) (a–f: 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 ppm, respectively at Eacc -1.1 V and tacc 40 s.

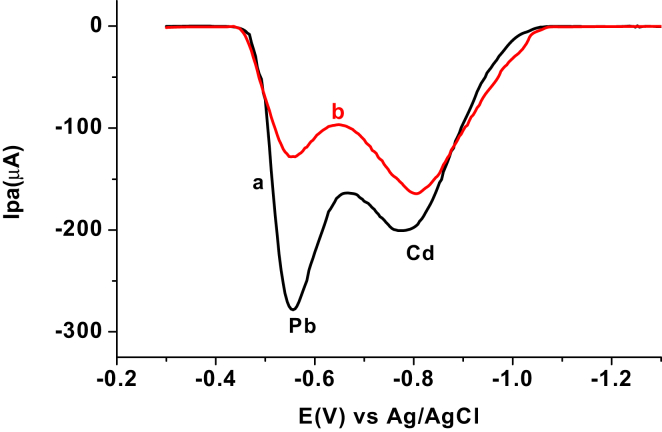

3.3. Simultaneous determination of Cd(II) and Pb(II) in textile effluent sample

Since it was confirmed that presence of one metal does not tamper with the determination of the other, the levels of Cd(II) and Pb(II) in effluent samples from Bahir Dar Textile factory were determined simultaneously. Figure 15 illustrates the SWASVs of the effluent sample collected from the site before (curve a) and after (curve b) the “treatment” plant. The two well resolved anodic peaks on each curve were assigned for Cd(II) and Pb(II) based on their characteristic anodic peak potential values. Levels of the two studied metals in the effluent samples before and after treatment are summarized in Table 1. While the concentrations of Pb(II) and Cd(II) in the textile factory effluent sample before treatment were 117.0 and 128.3 ppm, their concentrations in the discharged effluent sample after treatment were 17.7 and 101.4 ppm, respectively. Although the “treatment” has decreased the Pb(II) and Cd(II) to levels of 15.1% and 79.0%, respectively, still the metals in the effluent discharged directly to the Nile river are much larger than the maximum permissible limit (MPL) set by US EPA (2003) (as cited in [26]. The other trend observed from the results of the levels of the metals in the effluent before and after treatment is, the treatment process is more efficient on reduction of Pb(II) than on Cd(II) leading to conclude that the treatment mechanism the factory utilizes is more efficient to remove Pb(II) than Cd(II).

Figure 15.

SWASs AgNs/CPE in pH 6.0 ABS containing digested textile effluent sample collected (a) before treatment, and (b) after treatment at Eacc -1.1 V and tacc 40 s.

Table 1.

Levels of Cd (II) and Pb (II) in Bahir Dar textile factory effluent samples.

| Sampling point | Pb (II) (ppm) |

Cd (II) (ppm) |

Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| found | Permissible limit | found | Permissible limit | ||

| before treatment | 117.0 | ==== | 128.3 | ==== | === |

| after treatment | 17.7 | 0.5∗ | 101.4 | 1.0∗ | [27]∗ |

3.4. Recovery test for Cd(II) and Pb(II)

The accuracy of the method was evaluated using recovery result of spiked standards of the two studied metals in effluent sample collected from the site after treatment. 25 mL of unspiked sample and the same volume of sample spiked with 30 ppm of Pb(II) and Cd(II) both in pH 6 ABS were prepared for the recovery analysis for which the SWAS voltammograms were recoded (Figure 16). The percent of recovery of the added standard Cd (II) and Pb (II) in the effluent sample after treatment were 101.0% and 94.3%, respectively validating the method for simultaneous determination of the two metals in discharged textile effluent.

Figure 16.

SWASVs of discharged effluent sample after treatment in pH 6.0 ABS (a) unspiked and (b) spiked with 30 ppm of Cd(II) and Pb(II).

4. Conclusion

A sensitive and selective SWASV method using carbon paste electrode modified with green synthesized silver nanoparticles was developed for simultaneous determination of Pb(II) and Cd(II) in the discharged effluent of textile factory. The synthesized nanoparticles and hence modified electrode were characterized using UV-Vis, XRD, FT-IR, and cyclic voltammetric techniques. The applicability of the developed square wave anodic stripping voltammetric method for simultaneous determination of the two metals in textile discharged effluent sample was validated using its recovery results in the range 94.3–101% with an acceptable precision. The level of the two metals in the analyzed discharged effluent sample, even after its treatment, was much larger than the permissible limits showing poor efficiency of the “treatment plant” the factory claims to have.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Meareg Amare: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Awoke Worku: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Adane Kassa: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Woldegeorgis Hilluf: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Bradl H., editor. Heavy Metals in the Environment: Origin, Interaction and Remediation. Elsevier/Academic Press; London: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . World Health Organization; Switzerland, Geneva: 1996. Trace Elements in Human Nutrition and Health. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monisha J., Tenzin T., Naresh A., Blessy B.M., Krishnamurthy N.B. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdiscipl. Toxicol. 2014;7(2):60–72. doi: 10.2478/intox-2014-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarup L. Hazards of heavy metal contamination. Br. Med. Bull. 2003;68(1):167–182. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Losacco C., Perillo A. Metal-induced oxidative stress and cellular signaling alteration in animals. Iran. J. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2018;8(3):367–373. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ammann A.A. Speciation of heavy metals in environmental water by ion chromatography coupled to ICP-MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002;372:448–452. doi: 10.1007/s00216-001-1115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong S., Schirnding Y.E., Prapamontol T. Environmental lead exposure: a public health problem of global dimensions. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000;78:1068–1077. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/268221 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dokmeci A.H., Ongen A., Dagdeviren S. Environmental toxicity of cadmium and health effect. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2009;10(1):84–93. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273123192 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasegawa H., Rahman I.M., Rahman M.A., editors. Environmental Remediation Technologies for Metal-Contaminated Soils. Springer; Japan: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muhammd B.L. Determination of cadmium, chromium and lead from industrial wastewater in Kombolcha town, Ethiopia using FAAS. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2018;5(3):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alomary A.A., Belhadj S. Determination of heavy metals (Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Ni, Pb, Zn) by ICP-OES and their speciation in Algerian Mediterranean Sea sediments after a five-stage sequential extraction procedure. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2007;135:265–280. doi: 10.1007/s10661-007-9648-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yayintas O.T., Yilmaz S., Turkoglu M., Dilgin Y. Determination of heavy metal pollution with environmental physicochemical parameters in wastewater of Kocabas Stream (Biga, Canakkale, Turkey) by ICP-AES. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2007;127:389–397. doi: 10.1007/s10661-006-9288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saleh T.A., Khaled M.M., Rahim A.A. Electrochemical sensor for the determination of ketoconazole based on gold nanoparticles modified carbon paste electrode. J. Mol. Liq. 2018;256:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amare M. Electrochemical characterization of iron (III) doped zeolite-graphite composite modified glassy carbon electrode and its application for AdsASSWV determination of uric acid in human urine. Int. J. Ana. Chem. 2019;2019:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2019/6428072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thanh N.M., Van Hop N., Luyen N.D., Phong N.H., Toan T.T. Simultaneous determination of Zn(II), Cd(II), Pb(II), and Cu(II) using differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetry at a bismuth film-modified electrode. Ann. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019;2019:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallikarjuna K., Narasimha G., Dillip G.R., Praveen B., Shreedhar B., Lakshmi C.S., Reddy B.V., Raju B.D. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ocimum leaf extract and their characterization. Dig J Nanomater Bios. 2011;6(1):181–186. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/2637404 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H., Qian D., Xiao X., Deng C., Liao L., Deng J., Lin Y.W. Preparation and application of carbon paste electrode with multi walled carbon nanotubes and boron-embedded molecularly imprinted composite membranes. Bioelectrochemistry. 2018;121:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edgell K., Wilbers D. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, D.C.: 1989. USEPA Method Study 38 - SW-846 Method 3010, Acid Digestion of Aqueous Samples and Extracts for Trace Metals by FAAS. EPA/600/4-89/011 (NTIS PB89181945. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aziz W.J., Jassim H.A. Green chemistry for the preparation of silver nanoparticles using mint leaf leaves extracts and evaluation of their antimicrobial potential. World News Nat. Sci. 2018;18(2):163–170. www.worldnewsnaturalsciences.com Available online at. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nath S.S., Chakdar D., Gope G., Avasthi D.K. Effect of 100 Mev nickel ions on silica coated ZnS quantum dot. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 2008;3:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bykkam S., Ahmadipour M., Narisngam S., Kalagadda V.P., Chidurala S.C. Extensive studies on XRD of green synthesized silver nanoparticles. Adv. Nanoparticles. 2015;4(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dev N., Das A.K., Hossain M.A., Rahman S.M.M. Chemical composition of different extracts of Ocimum basilicum leaves. J. Sci. Res. 2010;3(1):197–206. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bard A.J., Faulkner L.R. second ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2001. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geremedhina W., Amare M., Admassie S. Electrochemically pretreated glassy carbon electrode for electrochemical detection of fenitrothion in tap water and human urine. Electrochim. Acta. 2013;87:749–755. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahesar S.A., Sherazi S.T., Niaz A., Bhanger M.I., Uddin S., Rauf A. Simultaneous assessment of zinc, cadmium, lead and copper in poultry feeds by differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetry. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010;48(8-9):2357–2360. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berehanu B., Lemma B., Tekle-Giorgis Y. Chemical composition of industrial effluents and their effect on the survival of fish and eutrophication of lake Hawassa, Southern Ethiopia. J. Environ. Protect. 2015;6(8):792–803. [Google Scholar]

- 27.March G., Nguyen T.D., Piro B. Modified electrodes used for electrochemical detection of metal ions in environmental analysis. Biosensors. 2015;5(2):241–275. doi: 10.3390/bios5020241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]