Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the health-related quality of life of uro-oncologic patients whose surgery was postponed without being rescheduled during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Patients and Methods

From the March 1 to April 26, 2020, major urologic surgeries were drastically reduced at our tertiary-care referral hospital. In order to evaluate health-related quality-of-life outcomes, the SF-36 questionnaire was sent to all patients scheduled for major surgery at our department 3 weeks after the cancellation of the planned surgical procedures because of the COVID-19 emergency.

Results

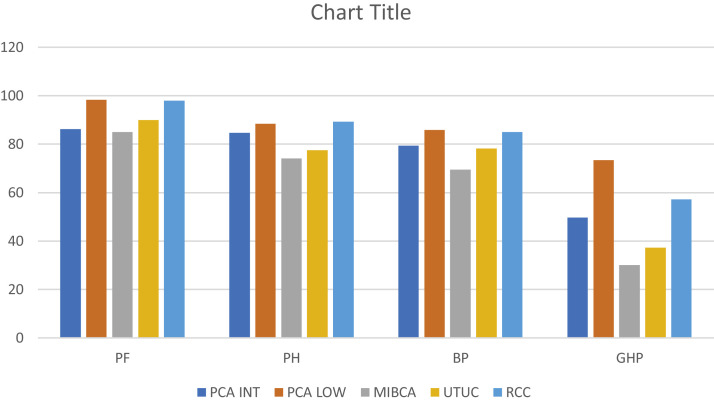

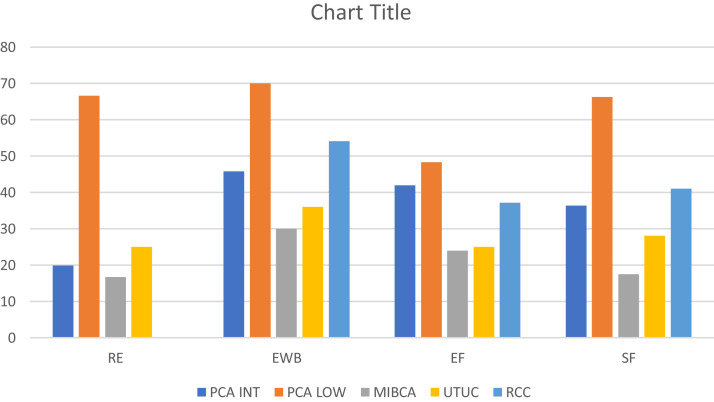

All patients included in the analysis had been awaiting surgery for a median (interquartile range) time of 52.85 (35-72) days. The SF-36 questionnaire measured 8 domains: physical functioning (PF), role limitations due to physical health (PH), role limitations due to emotional problems (RE), energy/fatigue (EF), emotional well-being (EWB), social functioning (SF), bodily pain (BP), general health perceptions (GHP). When considering physical characteristics as measured by the SF-36 questionnaire, PF was 91.5 (50-100) and PH was 82.75 (50-100) with a BP of 79.56 (45-90). For emotional and social aspects, RE was 36.83 (0-100) with a SF of 37.98 (12.5-90). Most patients reported loss of energy (EF 35.28 [15-55]) and increased anxiety (EWB 47.18 [interquartile range, 20-75]). All patients perceived a reduction of their health conditions, with GHP of 49.47 (15-85). Generally, 86% of patients (n = 43) noted an almost intact physical function but a significant emotional alteration characterized by a prevalence of anxiety and loss of energy.

Conclusion

The lockdown due to the novel coronavirus that has affected most operating rooms in Italy could be responsible for the increased anxiety and decrement in health status of oncologic patients. Without any effective solution, we should expect a new medical catastrophe—one caused by the increased risk of tumor progression and mortality in uro-oncologic patients.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Inflammation, Psychologic disorders, Quality of life, Uro-oncology

Micro-Abstract

In the last 3 months, we have experienced the beginning of a new era: a pandemic of the novel coronavirus. We investigated the health-related quality of life of oncologic patients whose surgery was postponed without being rescheduled. All patients perceived a reduction of their health conditions, and 86% noted prevalence of anxiety and loss of energy. Without any effective solution, we should expect the risk of increasing tumor progression and mortality in uro-oncologic patients.

Introduction

At the end of February 2020, a new era began: the pandemic of the novel coronavirus, which was found to be sufficiently divergent from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus to be considered a new human-infecting betacoronavirus,1 , 2 and which has completely changed our life.

On December 31, 2019, Chinese authorities notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of a novel coronavirus, now known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which was first reported in Wuhan, China.3 , 4 The virus has now spread worldwide, and on March 11, 2020, the WHO designated the disease caused by this virus, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), to be a pandemic.3 , 4 By April 3, 2020, a total of 1,131,000 confirmed cases and 59,000 deaths had been reported worldwide, with these numbers increasing rapidly every day. After China, Italy has been hit the hardest at beginning of the pandemic: 119,827 cases were reported as of April 3, 2020, with 14,681 deaths due to COVID-19 since the outbreak began.

As case numbers rapidly increased, European governments decided to apply a quarantine and isolation of the citizens in order to reduce the number of infections, thereby trying to avoid a collapse of the health care system. Practicing medicine has been greatly changed, and in Italy, doctors have been involved in this emergency and in the therapy of COVID-19 patients regardless of their medical specialization.

Just as healthy patients have experienced a life change as consequence of quarantine, so have oncologic patients. This situation has been especially amplified in north Italy, where the hospitals have virtually stopped their surgical activities. Considering that 1889 surgical procedures for renal cancer, 569 radical cystectomies, and 2631 radical prostatectomies (RPs) were performed in Lombardy in 2017, as reported by the Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM), we should pay attention to our oncologic patients.

Before the COVID-19 emergency, one of the most relevant problems of Italian health care system was the long wait list for oncologic procedures. Since the coronavirus pandemic broke out, all public and private hospitals in north Italy have focused on COVID-19 patients with severe breathing symptoms, as no therapeutic regimen has yet been proven effective for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2.5 But at the same time, it seems that the Italian health care system has forgotten oncologic patients, as no effective solution has been proposed to help these patients.

In this study, we investigated the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of oncologic patients who were scheduled for surgery in our department and whose procedures had been postponed without a new date being set.

Patients and Methods

Between January 1 and February 24, 2020, in our department, we had performed 51 major procedures for prostate cancer (PCa), renal cancer, and muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Of 51 procedures, 46 were performed by a robot-assisted or laparoscopic approach and 5 by open surgery.

From March 1 to April 26, 2020, as the daily rate of COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care units was consistently between 9% and 11% of all patients who are actively infected, our hospital decided to reduce surgical activity, and since then, only 3 robot-assisted RPs for high-risk PCa were performed at our department. Sixty-five planned major surgical procedures for oncologic diseases were cancelled and postponed indefinitely.

In order to evaluate patients’ HRQOL outcomes, the SF-36 questionnaire (Supplemental Appendix in the online version)6 , 7 was sent by e-mail to all oncologic patients scheduled for major surgery at our department 3 weeks after the cancellation of the operation due to the COVID-19 emergency.

The SF-36 consisted of 36 multiple-choice questions measuring 8 distinct domains: physical functioning (PF), role limitations due to physical health (PH), role limitations due to emotional problems (RE), energy/fatigue (EF), emotional well-being (EWB), social functioning (SF), bodily pain (BP), and general health perceptions (GHP). Scores for each scale ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher function or well-being.8 , 9

The patients were divided according to the disease into 4 groups: PCa (planned for RP), muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC, planned for radical cystectomy), upper urinary tract urothelial cancer (planned for radical nephroureterectomy) and renal-cell carcinoma (planned for partial/radical nephrectomy).

Patients with PCa were stratified according to the D’Amico risk criteria10 on clinical features: low risk (prostate-specific antigen [PSA] ≤ 10 ng/mL, ≤ cT2a, and biopsy Gleason ≤ 6), intermediate risk (PSA > 10 and ≤ 20 ng/mL, cT2b, or biopsy Gleason 7), and high risk (PSA > 20 ng/mL, lower than cT2b, or biopsy Gleason score ≥ 8). External beam radiotherapy was proposed as alternative therapy for PCa, but it was refused by all patients scheduled for robot-assisted RP.

Patients with advanced tumor stage (PCa high risk according to D’Amico criteria, or locally advanced or with nodal clinical disease, renal cancer with inferior vena cava thrombus and MIBC > pT3) were excluded from the analysis. Moreover, we also excluded patients with psychic or distress disorders such as anxiety and depression, or Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) > 2 at diagnosis and before the COVID-19 emergency.11

Results

Fifty patients were included in the analysis, whereas 15 patients did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thirty-four patients had PCa (26 intermediate risk and 8 low risk), 5 patients pT2G3 MIBC, 4 patients nonmetastatic upper tract urothelial carcinoma, and 7 cT1b RCC with a median (interquartile range [IQR]) tumor size of 4.5 (2.8-6) cm. Median age was 65.5 years old, and median (IQR) CCI was 1.39 (0-2). Thirty-eight patients were male and 12 female.

All patients included in the analysis had been awaiting surgery for a median (IQR) of 52.85 (35-72) days. All patients were married and lived with their families. Thirty-five patients were employed full time, and 15 patients were retired. Table 1 summarizes the clinical and pathologic characteristics of the patients enrolled onto the study.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics of 50 Patients

| Patients | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex (n) | |

| Male | 38 |

| Female | 12 |

| Oncologic diseases (n) | |

| Prostate cancer, intermediate risk | 26 |

| Prostate cancer, low risk | 8 |

| MIBC (pT2G3) | 5 |

| UTUC | 4 |

| Renal cancer (cT1b) | 7 |

| Median CCI | |

| Total | 1.39 |

| Prostate cancer | 0.94 |

| MIBC | 1.6 |

| UTUC | 1.75 |

| Renal cancer | 1.29 |

| Median age (years) | |

| Total | 65.5 |

| Prostate cancer | 64.6 |

| MIBC | 68 |

| UTUC | 72 |

| Renal cancer | 57.3 |

| Median wait time for surgery in COVID-19 period (days) | |

| Total | 52.85 |

| Prostate cancer | 51.77 |

| Prostate cancer, low risk | 58.7 |

| MIBC | 56 |

| UTUC | 45 |

| Renal cancer | 41 |

| Marital status (n) | |

| Married | 50 |

| Not married | 0 |

| Occupation (n) | |

| Full-time employed | 35 |

| Retired | 15 |

| Not employed | 0 |

Abbreviations: CCI = Charlson comorbidity index; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; MIBC = muscle-invasive bladder cancer; UTUC = upper tract urothelial carcinoma.

When considering physical characteristics, median (IQR) PF was 91.5 (50-100) and PH was 82.75 (50-100) with a BP of 79.56 (45-90). For the emotional and social aspects, RE was 36.83 (0-100) and SF 37.98 (12.5-90). Most patients reported a loss of energy (EF 35.28 [15-55]) and increased anxiety (EWB 47.18 [20-75]). Although the variable prognosis reported for the genitourinary tumors and addressed what could differently influence HRQOL outcomes, surprisingly, all patients perceived a reduction in their health conditions with a GHP of 49.47 (15-85) (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

SF-36 Outcomes

| Characteristic | Value | IQR |

|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning (PF) | ||

| Total | 91.5 | 50-100 |

| Prostate cancer, intermediate risk | 86.25 | 50-100 |

| Prostate cancer, low risk | 98.33 | 95-100 |

| MIBC | 85 | 80-90 |

| UTUC | 90 | 85-95 |

| Renal cancer | 97.9 | 90-100 |

| Role limitations due to physical health (PH) | ||

| Total | 82.75 | 50-100 |

| Prostate cancer, intermediate risk | 84.62 | 50-100 |

| Prostate cancer, low risk | 88.33 | 75-100 |

| MIBC | 74 | 50-85 |

| UTUC | 77.5 | 50-95 |

| Renal cancer | 89.28 | 75-100 |

| Bodily pain (BP) | ||

| Total | 79.56 | 45-90 |

| Prostate cancer, intermediate risk | 79.43 | 45-90 |

| Prostate cancer, low risk | 85.83 | 75.5-90 |

| MIBC | 69.5 | 45-90 |

| UTUC | 78.12 | 67.5-90 |

| Renal cancer | 85 | 67.5-90 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems (RE) | ||

| Total | 36.83 | 0-100 |

| Prostate cancer, intermediate risk | 19.87 | 0-100 |

| Prostate cancer, low risk | 66.67 | 33.3-100 |

| MIBC | 16.66 | 0-33.3 |

| UTUC | 25 | 0-66.7 |

| Renal cancer | 55.94 | 25-100 |

| Emotional well-being (EWB) | ||

| Total | 47.18 | 20-75 |

| Prostate cancer, intermediate risk | 45.77 | 24-75 |

| Prostate cancer, low risk | 70 | 60-75 |

| MIBC | 30 | 20-48 |

| UTUC | 36 | 24-52 |

| Renal cancer | 54.14 | 36-75 |

| Energy/fatigue (EF) | ||

| Total | 35.28 | 15-55 |

| Prostate cancer, intermediate risk | 41.93 | 20-55 |

| Prostate cancer, low risk | 48.33 | 45-55 |

| MIBC | 24 | 15-35 |

| UTUC | 25 | 20-35 |

| Renal cancer | 37.15 | 20-55 |

| Social functioning (SF) | ||

| Total | 37.98 | 12.5-90 |

| Prostate cancer, intermediate risk | 36.31 | 12.5-90 |

| Prostate cancer, low risk | 66.33 | 50-90 |

| MIBC | 17.5 | 12.5-25 |

| UTUC | 28.12 | 12.5-25 |

| Renal cancer | 41.08 | 25-50 |

| General health perceptions (GHP) | ||

| Total | 49.47 | 15-85 |

| Prostate cancer, intermediate risk | 49.62 | 15-85 |

| Prostate cancer, low risk | 73.33 | 50-85 |

| MIBC | 30 | 15-40 |

| UTUC | 37.25 | 29-45 |

| Renal cancer | 57.15 | 40-85 |

Abbreviations: IQR = interquartile range; MIBC = muscle-invasive bladder cancer; UTUC = upper tract urothelial carcinoma.

Generally, 86% of patients (n = 43) reported an almost intact physical function but a significant emotional alteration characterized by a prevalence of anxiety and loss of energy (Figures 1 and 2 )

Figure 1.

Physical Aspects and General Health Perception According to SF-36 Eight Domains

Figure 2.

Emotional Aspects According to SF-36 Eight Domains

Discussion

As COVID-19 spread around the globe, governments have imposed quarantines and isolation on an unprecedented scale. China locked down entire cities; in Italy, our politicians have imposed draconian restrictions throughout the country. In the United States, thousands of people have been subjected to legally enforceable quarantines or are in self-quarantine. The US federal government has also banned entry by non–US nationals traveling from China, Iran, and most of Europe and is screening passengers returning from heavily affected countries. Still, the numbers of cases and deaths continue to rise.12

Unfortunately, since the COVID-19 outbreak in our region, Italian government focused its attention exclusively on COVID-19 patients, with those patients who were not infected by the virus but who needed access to health care system because of their cancer seemingly forgotten.

Stensland et al13 provided a list of surgeries, including radical cystectomy, radical nephroureterectomy, nephrectomy for cT3+ disease, and RP for high-risk patients, that ought to be prioritized if COVID-19 surges warranted cancellation of most elective surgeries. Furthermore, Campi et al14 suggested that approximately two thirds of elective major uro-oncologic surgeries could be safely postponed or changed to another treatment modality when the availability of health care resources was reduced. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis by Wang et al15 highlighted that RP was associated with higher overall and cancer-specific survival when compared to radiotherapy, also considering that a real multimodal approach can be probably applied for patients choosing RP, whereas patients choosing radiotherapy first rarely receive salvage RP.

Although the recent recommendations of a panel of Italian urologists on pathways of pre-, intra-, and postoperative care for urologic patients undergoing urgent procedures or nondeferrable oncologic interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic,16 most planned surgical procedures in Lombardy were cancelled between March and April 2020.

In this study, we focused for the first time in the literature on the impact of postponement of surgeries due to the COVID-19 emergency on the on HRQOL of uro-oncologic patients by using the SF-36 questionnaire.

When evaluating the results of the questionnaire, we found that most patients (86%) reported an almost normal physical activity but a loss of energy and increased anxiety and depression. In order to avoid bias, we excluded from analysis all patients with severe comorbidities (CCI > 2) and/or patients who showed psychologic or distress disorders before the COVID-19 emergency. Furthermore, we also excluded patients with advanced or metastatic tumors, where disease could represent the first reason for anxiety and depression.

Generally, all patients perceived a reduction of their health condition, with a median (IQR) GHP of 50.45 (15-85). Recent research findings in individuals with distress disorders, such as major depression and anxiety disorders, suggest that inflammation plays an important role in the pathophysiology of these conditions,17 , 18 and inflammatory biomarkers are elevated in many patients with major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders.19 Moreover, fatigue impact, pain effects, depression symptoms, and anxiety symptoms are associated with work and general activity impairment.20

Clinically relevant anxiety occurs in 7% to 30% of oncologic patients and 20% to 40% of their family caregivers.21 , 22 It is often characterized by dyspnea, fatigue, nausea, and pain, as well as a poorer quality of life.23 , 24 Furthermore, most of these reported studies also highlighted a significant association between higher levels of anxiety and depression and a decrease in health status.

On the basis of the evidence that supports a role for inflammatory mediators in stress and anxiety,25 in 2015 Miaskowski et al26 investigated the associations between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine genes and levels of trait and state anxiety. This study demonstrated that variations in 3 cytokine genes (interleukin [IL]-1β, IL-1 receptor 2 [IL1R2], and nuclear factor kappa beta 2 [NFκB2]) were associated with trait anxiety, and variations in two genes (IL1R2, tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNFA]) were associated with state anxiety, thus contributing to higher levels of anxiety in oncologic patients and their family caregivers. Indeed, on the basis of the data concerning the incidence of urologic tumors, we hypothesize that there will be a further extension in Italy of the wait list for cancer diseases, which could be subsequently associated with an increased risk of psychologic disorders and decrements in health status in oncologic patients.

In 2018, Ferlay et al27 evaluated cancer incidence and mortality estimates for 25 major cancers in Europe; PCa had an incidence of 449,800 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, bladder cancer 197,100/100,000, and renal cancer 136,500/100,000.

Should hospitals continue to reduce their elective surgical activity because of the COVID-19 pandemic, it could take several months to treat all the oncologic patients awaiting surgery. Further, we should also consider the fact that most of oncologic patients will require a clinical restaging of their disease, thus increasing wait time for surgery and health care spending.

The limitations of the study include the small cohort of included patients and the lack of a control group. Nevertheless, we believe that the sample is sufficiently reliable to reveal the true physical and emotional conditions of our patients waiting for oncologic surgery during the COVID-19 emergency.

Conclusion

The lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has affected most operating rooms in Italy, has resulted in increased anxiety and decrements in health status of oncologic patients.

Considering the actual data on cancer incidence, institutions should make a great effort to organize new COVID-19–free hospitals, which could face the new emergency represented by the lengthy surgical wait list for uro-oncologic diseases.

Without any effective solution, we should expect a new medical catastrophe that won’t be caused by the novel coronavirus but rather by the increased risk of tumor progression and mortality in these patients with a confined tumor disease, and who could be probably saved by an immediate surgical procedure.

Clinical Practice Points

-

•

In the last 3 months, we have experienced the beginning of a new era: a pandemic of the new coronavirus, COVID-19. European governments decided to apply a quarantine and isolation of the citizens in order to reduce the number of infections. Healthy patients have experienced a change in their lives, but oncologic patients are experiencing a new drama.

-

•

Several major surgeries in urology has been postponed without being rescheduled. This has been responsible for a reduction of the health conditions and a significant emotional alteration in uro-oncologic patients.

-

•

Without any effective solution, we should expect a new catastrophe not due to coronavirus but to the risk of tumor progression and mortality in those patients who actually have a confined tumor disease and could probably be saved by surgical therapy.

Disclosure

The authors have stated that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material accompanying this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clgc.2020.07.008.

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Rothan H.A., Byrareddy S.N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naspro R., Da Pozzo L.F. Urology in the time of corona. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41585-020-0312-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sohrabi C., Alsafi Z., O’Neill N., et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int J Surg. 2020;79:233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., et al. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satkunasivam R., Santomauro M., Chopra S., et al. Robotic intracorporeal orthotopic neobladder: urodynamic outcomes, urinary function, and health-related quality of life. Eur Urol. 2016;69:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novara G., Secco S., Botteri M., De Marco V., Artibani W., Ficarra V. Factors predicting health-related quality of life recovery in patients undergoing surgical treatment for renal tumors: prospective evaluation using the RAND SF-36 Health Survey. Eur Urol. 2010;57:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware J.E., Jr., Sherbourne C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hays R.D., Sherbourne C.D., Mazel R.M. The RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0. Health Econ. 1993;2:217–227. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730020305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Amico A.V., Whittington R., Malkowicz S.B., et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969–974. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park J.W., Koh D.H., Jang W.S., et al. Age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index as a prognostic factor for radical prostatectomy outcomes of very high-risk prostate cancer patients. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0199365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parmet W.E., Sinha M.S. COVID-19—the law and limits of quarantine. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2004211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stensland K.D., Morgan T.M., Moinzadeh A., et al. Considerations in the triage of urologic surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol. 2020;77:663–666. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campi R., Amparore D., Capitanio U., et al. Assessing the burden of nondeferrable major uro-oncologic surgery to guide prioritisation strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from three Italian high-volume referral centres. Eur Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z., Ni Y., Chen J., et al. The efficacy and safety of radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy in high-risk prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2020;18:42. doi: 10.1186/s12957-020-01824-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simonato A., Giannarini G., Abrate A., et al. Pathways for urology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2020 doi: 10.23736/S0393-2249.20.03861-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Husain M.I., Strawbridge R., Stokes P.R., Young A.H. Anti-inflammatory treatments for mood disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31:1137–1148. doi: 10.1177/0269881117725711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu C.S., Adibfar A., Herrmann N., Gallagher D., Lanctot K.L. Evidence for inflammation-associated depression. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2017;31:3–30. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felger J.C. Imaging the role of inflammation in mood and anxiety-related disorders. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16:533–558. doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666171123201142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enns M.W., Bernstein C.N., Kroeker K., et al. The association of fatigue, pain, depression and anxiety with work and activity impairment in immune mediated inflammatory diseases. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0198975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cliff A., MacDonagh R. Psychosocial morbidity in prostate cancer: II. A comparison of patients and partners. BJU Int. 2000;86:834–839. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linden W., Vodermaier A., Mackenzie R., Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruera E., Schmitz B., Pither J., Neumann C.M., Hanson J. The frequency and correlates of dyspnea in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:357–362. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith E.M., Gomm S.A., Dickens C.M. Assessing the independent contribution to quality of life from anxiety and depression in patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2003;17:509–513. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm781oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogelzangs N., Beekman A.T., de Jonge P., Penninx B.W. Anxiety disorders and inflammation in a large adult cohort. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e249. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miaskowski C., Cataldo J.K., Baggott C.R., et al. Cytokine gene variations associated with trait and state anxiety in oncology patients and their family caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:953–965. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2443-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferlay J., Colombet M., Soerjomataram I., et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:356–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.